94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 10 July 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1212568

This article is part of the Research TopicCultural Considerations in Relation to Mental Health StigmaView all 10 articles

I. E. van Beukering1,2*†

I. E. van Beukering1,2*† G. Sampogna3†

G. Sampogna3† M. Bakker4

M. Bakker4 M. C. W. Joosen1

M. C. W. Joosen1 C. S. Dewa5

C. S. Dewa5 J. van Weeghel1

J. van Weeghel1 C. Henderson6

C. Henderson6 E. P. M. Brouwers1

E. P. M. Brouwers1Introduction: Workplace mental health stigma is a major problem as it can lead to adverse occupational outcomes and reduced well-being. Although workplace climate is largely determined by managers and co-workers, the role of co-workers in workplace stigma is understudied. Therefore, the aims are: (1) to examine knowledge and attitudes towards having a coworker with Mental Health Issues or Illness (MHI), especially concerning the desire for social distance, (2) to identify distinct subgroups of workers based on their potential concerns towards having a coworker with MHI, and (3) to characterize these subgroups in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and background characteristics.

Materials and methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among a nationally representative internet panel of 1,224 Dutch workers who had paid jobs and did not hold management positions. Descriptive statistics and a three-step approach Latent Class Analysis (LCA) were used to address the research aims.

Results: Concerning the desire for social distance, 41.9% of Dutch workers indicated they did not want to have a close colleague with MHI, and 64.1% did not want to work for a higher-ranking manager who had MHI. In contrast however, most workers did not have negative experiences with interacting with coworkers with MHI (92.6%). Next, five distinct subgroups (SG) of workers were identified: two subgroups with few concerns towards having a coworker with MHI (SG1 and SG2; 51.8% of the respondents), one subgroup with average concerns (SG3; 22.7% of the respondents), and two subgroups with more concerns (SG4 and SG5; 25.6% of the respondents). Four out of five subgroups showed a high tendency towards the desire for social distance. Nevertheless, even in the subgroups with more concerns, (almost) half of the respondents were willing to learn more about how to best deal with coworkers with MHI. No significant differences were found between the subgroups on background characteristics.

Discussion: The high tendency to the desire for social distance seems to contrast with the low number of respondents who personally had negative experiences with workers with MHI in the workplace. This suggests that the tendency to socially exclude this group was not based on their own experience. The finding that a large group of respondents indicated to want to learn more about how to deal with a co-worker with MHI is promising. Destigmatizing interventions in the workplace are needed in order to create more inclusive workplaces to improve sustained employment of people with MHI. These interventions should focus on increasing the knowledge of workers about how to best communicate and deal with coworkers with MHI, they do not need to differentiate in background variables of workers.

Mental health stigma and discrimination in the workplace are a major problem for people with Mental Health Issues or Illness (MHI) (1, 2). The concept of stigma consists of three dimensions, problems with: knowledge (misinformation of ignorance), attitudes (prejudice), and behaviour (discrimination) (3). Stigma and discrimination can lead to adverse occupational outcomes and reduced well-being (4). Multiple large studies showed that people with MHI face stigma and discrimination at work. For instance, a study on discrimination among workers with major depressive disorder from 35 countries showed that 62.5% had anticipated and/or experienced discrimination at work (5). Also, a recent study showed that 64% of Dutch line managers were reluctant to hire a job applicant with a mental health issue (6). In addition, 68.4% of Dutch workers expected that disclosure during a temporary contract would decrease the chance that a contract would be renewed, and 56.6% expected that disclosure would lead to a diminished chance to be promoted to a higher position in the future (7). MHI affect a large part of the population, almost half of the adults (48%) in Netherlands (18–75 years old) has ever had one or more mental illnesses (8). As employment is important for health and well-being, workplace stigma and discrimination should be seen as a public health problem.

A recent systematic review showed that most publications on workplace stigma were focused on the roles of employers, while less is known about the roles of workers (9). However, workers have also found to be influential stakeholders with stigmatizing attitudes in the workplace (10). In an American study, workers were found to have concerns about competencies of coworkers with MHI and held unfavourable attitudes to work with a person with MHI (11). Furthermore, mental health stigma by workers can lead to bullying, harassment (11, 12) or social exclusion of people with MHI in the workplace (13). One study showed that examples of social exclusion (or more specific: the desire for social distance) are not wanting to working for or with people with MHI or excluding coworkers from social events at work (11).

Anti-stigma interventions can lead to more inclusive workplaces (14, 15). More specifically, these interventions can help to improve sustained employment of people with MHI by increasing workers’ knowledge and helping behaviours (15). Evaluating how processes of stigma are perpetuated in the workplace is essential for guiding the development of anti-stigma interventions (16). One hindering or perpetuating factor can be legislation (17), as are cultural differences (18), which may need to be taken into account when developing destigmatizing interventions. Anti-stigma interventions need to address the diverse needs of the stakeholders in the workplace (19). This way anti-stigma interventions can differentiate in the messages to each target group and therefore be more effective.

In Netherlands, several studies have shown that a variety of workplace stakeholders tend to have negative attitudes towards people with MHI, such as HR managers, line managers and coworkers (1, 6, 7, 19, 20). However, research on this topic is very scarce in Netherlands, especially on attitudes of workers in non-managerial positions, who often make up a large part of the social work environment. If we want to develop effective anti-stigma interventions, we first need to better understand the nature of those negative attitudes, and high quality research on the nature of these stakeholders’ concerns is needed. As such, we used a large and representative sample to study the following aims: (1) to examine knowledge and attitudes towards having a coworker with MHI, especially concerning the desire for social distance, (2) to identify distinct subgroups of workers based on their potential concerns towards having a coworker with MHI, and (3) to characterize these subgroups in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and background characteristics.

In February 2018, a cross-sectional survey was conducted among a nationally representative internet panel of Dutch workers. Data were collected among an existing panel (Longitudinal Internet Studies for Social Sciences, LISS) administered by CentERdata, which is a Dutch research institute specialized in data collection. The existing panel is a random and representative selection of 5,000 Dutch households (7,357 panel members). The questionnaires include domains like education, work, housing, time use, income, political views, values, and personalities. Three reminders were sent to panel members to increase the response rate, see www.lissdata.nl for more information.

The questionnaire was sent to 1,671 Dutch adults who participated in the panel, had paid jobs, and did not hold management positions. Ethical Approval was obtained by the Ethics Review Board of the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences of Tilburg University (registration number: RP193).

In Netherlands, the Gatekeeper Improvement Act and the Extended Payment of Income Act protect Dutch workers with disabilities. The Gatekeeper Improvement Act states that employers, the occupational physician (OP), and the worker, are responsible for the benefits and reintegration when workers are absent due to the occurrence of sickness. Workers have to meet with an OP when sickness absence occurs. The OP is responsible for performing an independent assessment which in cooperation with the worker leads to a reintegration plan. The Extended Payment of Income Act states that employers pay at least 70% of the income for the first 2 years of sickness absence. During these first 2 years employers are not allowed to fire the worker. There is no obligation to disclose MHI in the workplace.

At present, validated instruments to measure workplace stigma are scarce (4), and especially questionnaires focusing on workers’ attitudes are lacking. Therefore, a questionnaire was developed using a multistep procedure to address the aims of this study. To this end, first, the existing literature on the topic of workplace mental health stigma and discrimination was searched. The main topics of the questionnaire were identified based on the theoretical stigma model proposed by Thornicroft et al. (2007) (3). Specifically, the items on knowledge and attitudes were based on literature of workplace stakeholders’ knowledge, experience, and attitudes (21, 22). Second, the main topics found and the subsequent proposed items on the questionnaire were discussed with international experts in the field of mental health and stigma (both senior researchers and experts by experience) to modify and improve the questionnaire. Third, the questionnaire was pilot tested (e.g., concerning clarity) within the researchers’ network (N = 18) and improved where necessary based on the feedback received. This resulted in the final version of the questionnaire. The items used for this study can be found in Supplementary material Appendix 1. The following topics and items were addressed:

Knowledge

• Respondents were asked to indicate the percentage of coworkers they thought will be affected in their organization by MHI during their working life. The ratio response category ranged from 0 to 100%. Due to the distribution of the variable, the variable was converted to 0 (<15%), 1 (15–25%), and 2 (>25%).

• A set of 15 items of different types of MHI, the respondents were asked about which type of MHI they think of when hearing or reading about ‘a coworker with MHI’. The response categories were 0 (no) and 1 (yes). The items were converted into three dichotomous variables. Association with stress, mental/emotional exhaustion, and burnout were merged into ‘association with work related mental disorders’ because these are the most important reasons for work related sickness absence in Netherlands (23). Association with anxiety, depression, addiction, and obsessive–compulsive disorder was converted into ‘association with common mental disorders’ because these disorders typically refer to common mental disorders. Association with other disorders like manic depressive/bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline disorder, autism, psychosis, and eating disorder was merged into ‘association with other mental disorders’.

Personal experience

• As personal experience is a source of knowledge, it was assessed if respondents knew anyone with MHI (i.e., general familiarity with MHI). To assess general familiarity with MHI, the Level of Contact Report was used (24). Therefore, general familiarity with MHI was measured by a set of 9 items, these items represent different kinds of relationships. The nominal response categories were 0 (no) and 1 (yes). To create the general familiarity variable, the individual items were converted into the following categories: 0 (not familiar) if respondents did not know anyone who had or had had MHI; 1 (little familiar) when respondents indicated to know a family member who they had little contact with and/or an acquaintance and/or a coworker with who they did not work much with MHI, and 2 (very familiar) when respondents indicated to know a family member who they had a lot of contact with and/or a friend and/or a coworker with whom worked or had worked intensively with MHI.

• Respondents’ actual experience with interacting with coworkers with MHI in the workplace. The response categories of this single item were 1 (very unfavourable), 2 (rather unfavourable), 3 (neutral), 4 (rather favourable), 5 (very favourable), and 6 (not applicable/no experience with this). Personal experience was converted into the categories 0 (negative = very unfavourable/rather unfavourable), 1 (neutral = neutral), 2 (positive = rather favourable/very favourable), and 3 (none = not applicable/no experience with this).

The desire for social distance

• A set of three items measured the desire for social distance, asking the respondent to what extent they would (1) want to have a coworker who had MHI (but who they would hardly work with), (2) want to have a coworker who had MHI (and who they would work with intensively), and (3) want to work for a higher-ranking manager with MHI. The response categories were 1 (absolutely not), 2 (rather not), 3 (neutral), 4 (would not mind), 5 (would like to very much), and 6 (not applicable). The response categories were merged into the categories 0 (no = absolutely not/rather not), 1 (neutral = neutral/not applicable), and 2 (yes = would not mind/would like to very much).

Willingness to support a coworker with MHI

• A set of six items measured willingness to support a coworker with MHI. Five items asking to what extent respondents agreed with the following statements: (1) I will free up extra time for a coworker with MHI so that we can talk about his/her MHI, (2) I am happy to offer practical support to a coworker with MHI, for example by temporarily taking on some of his/her work, (3) I find it hard to work with a coworker with MHI, (4) I would like to learn more about MHI in general, and (5) I would like to learn more about how I can best deal with coworkers with MHI. The response categories were 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (slightly disagree), 3 (neutral), 4 (slightly agree), and 5 (strongly agree). And additionally, one item (6) asking the respondent to what extent they would (1) want to know if a coworker has MHI. The response categories were 1 (absolutely not), 2 (rather not), 3 (neutral), 4 (would not mind), 5 (would like to very much), and 6 (not applicable). The response categories of the seven items were merged into the categories 0 (no = strongly disagree/slightly disagree/absolutely not/rather not), 1 (neutral = neutral/not applicable), and 2 (yes = slightly agree/strongly agree/would not mind/would like to very much).

Responsibility

• One item measured if workers agreed with the following statement: (1) people are mainly responsible for their MHI. This item was added because attribution of personal responsibility can contribute to stigmatizing attitudes (24). The response categories were 1 (absolutely not), 2 (rather not), 3 (neutral), 4 (would not mind), 5 (would like to very much), and 6 (not applicable). The response categories of the item were merged into the categories 0 (no = strongly disagree/slightly disagree/absolutely not/rather not), 1 (neutral = neutral/not applicable), and 2 (yes = slightly agree/strongly agree/would not mind/would like to very much).

Potential concerns

• A set of 15 items about potential concerns having a coworker with MHI, like: I need to take over his/her duties, I am not sure how to help this coworker, and the coworker will make mistakes. The items were categorized in concerns about incompetency, concerns about helping and dealing with coworker with MHI, and concerns about that the coworker with MHI will damage the workplace. The response categories were 0 (no) and 1 (yes). These specific items were derived from literature on beliefs as barriers to employment (25, 26).

• Several background characteristics were included in this study because they were expected to be associated with stigma, based on previous research (1, 27, 28). A personal characteristic, personally having (had) MHI, was included. This self-reported variable measured whether workers have (or have had) MHI, it was merged into 0 (no = no/I do not know) and 1 (yes = yes). Sociodemographic characteristics were added, i.e., age, gender, educational level, and marital status. Educational level was converted into the categories 0 (low = primary school/intermediate secondary), 1 (secondary = higher secondary education/preparatory university education) and 2 (high = higher education). Marital status was converted into the categories 0 (unmarried = separated/divorced/widow or widower/never been married) and 1 (married = married). The work-related characteristics included were gross income per month, type of industry, company size and workplace atmosphere. Type of industry was merged into 0 (private = agriculture, forestry, fishery, and hunting/mining/industrial production/utilities production, distribution, and trade/construction/retail trade/catering/transport, storage, and communication/finance/business services) and 1 (public = governments services, public administration, and mandatory social insurances/education/healthcare and welfare). Following the definition of the European Commission (Commission Recommendation 96/280/EC), company size was changed into 0 (small; ≤ 49 workers) and 1 (medium or large; ≥ 50 workers). The item ‘In my organization it is customary to look down on workers with MHI’ was converted into workplace atmosphere with the categories 0 (negative = slightly agree/strongly agree), 1 (neutral = neutral), and 2 (positive = strongly disagree/slightly disagree).

To address the first research aim (i.e., to examine Dutch workers’ knowledge and attitudes towards having a coworker with MHI, especially concerning the desire for social distance), descriptive statistics were used (means, standard deviations, and frequency table).

For the second and third research aim (i.e., to identify distinct subgroups of workers based on their concerns about having a coworker with MHI, and to characterize these subgroups in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and background characteristics), a three-step approach Latent Class Analysis (LCA) was used. In the first step, a latent class model was built using the 15 items that measured potential concerns. In the second step, workers were assigned to the different subgroups. In the last step, the characteristics (i.e., knowledge, experience, attitudes, and background characteristics) that were associated with the different subgroups were evaluated.

In the first step of the LCA, the most suitable number of subgroups (classes) was identified by using several fit indices. The three fit indices that were used were the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the Akaike information criterion (AIC), and the Akaike information criterion with 3 as penalizing factor (AIC3). These indices weight the fit and parsimoniousness of the model (the best model has the lowest criteria), and the BIC is seen as the best performing goodness-of-fit indice (29). Furthermore, a bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) (30), was used to compare the different models. Lastly, the theoretical interpretation of the model was taken into account. The size of the smallest subgroup had to be at least 5% of the total sample size (31).

In the second step, the workers were assigned to the latent subgroup based on the posterior subgroup membership probability.

In the third step, to characterize the subgroups the associations with knowledge, attitudes, and background characteristics were examined. Some items contained missing data (i.e., company size and gross income per month), Latent GOLD’s imputation procedure helped imputing these missing data (32). Wald tests (p < 0.05) were used to examine whether there were differences between the subgroups.

SPSS version 24 was used for the data preparation and descriptive analyses and Latent GOLD 6.0 was used for the three-step approach LCA (33).

A total of 1,224 respondents with paid jobs (and who were not working in management positions) filled out the questionnaire (response rate = 73.5%), 27.9% of the respondents indicated that they had a current or past MHI. Slightly more respondents were female (57.1%) and they had an average age of 44.6 years (SD = 12.1). More characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 2 shows that most of the respondents thought that less than 25% of the coworkers in their organization would be affected by MHI during their working life. Also, most respondents were thinking of work related disorders when they heard or read about ‘a coworker with MHI’ (71.7%) and fewer respondents thought of common or other (more severe) mental disorders. Three quarters of the respondents were familiar in general with MHI, and a quarter indicated that they did not know anyone who had or had had MHI (27.2%). Most respondents did not have negative personal experiences with interacting with coworkers with MHI (92.6%).

Table 2 also shows the exploration of the attitudes towards having a coworker with MHI. Concerning the desire for social distance, a large proportion of respondents did not want to have a coworker with MHI if they have to work with them intensively (41.9%) or, a smaller proportion of workers, if they would hardly have to work with them (21.9%). The majority would not want to work for a higher-ranking manager who had MHI (64.1%). Though, the majority of the respondents would be willing to free up extra time for a coworker with MHI so that they can talk about his/her problems (60.4%) and is happy to offer practical support (58.7%). Almost half of the respondents would like to learn more about how they can best deal with coworkers with MHI (49.5%) or would like to learn more about MHI in general (34.6%). More than half of the respondents indicated that people are mainly personally responsible for their MHI (53.6%). Most frequently reported were the concerns that a coworker with MHI would not be able to handle the work (45.0%) and that respondents do not know how to help a coworker with MHI (38.0%). A small part of the respondents (14.8%) reported not having any concerns.

Five distinct subgroups of workers can be distinguished based on the LCA. Table 3 shows the model fit indices for models with 1 to 10 classes. Both the BIC and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test suggest a five-class model, while the AIC suggests a 10-class model and the AIC3 a three-class model. Further inspection of the different models showed that the five-class model was both parsimonious and had a good theoretical interpretation. Therefore, the five-class solution was chosen.

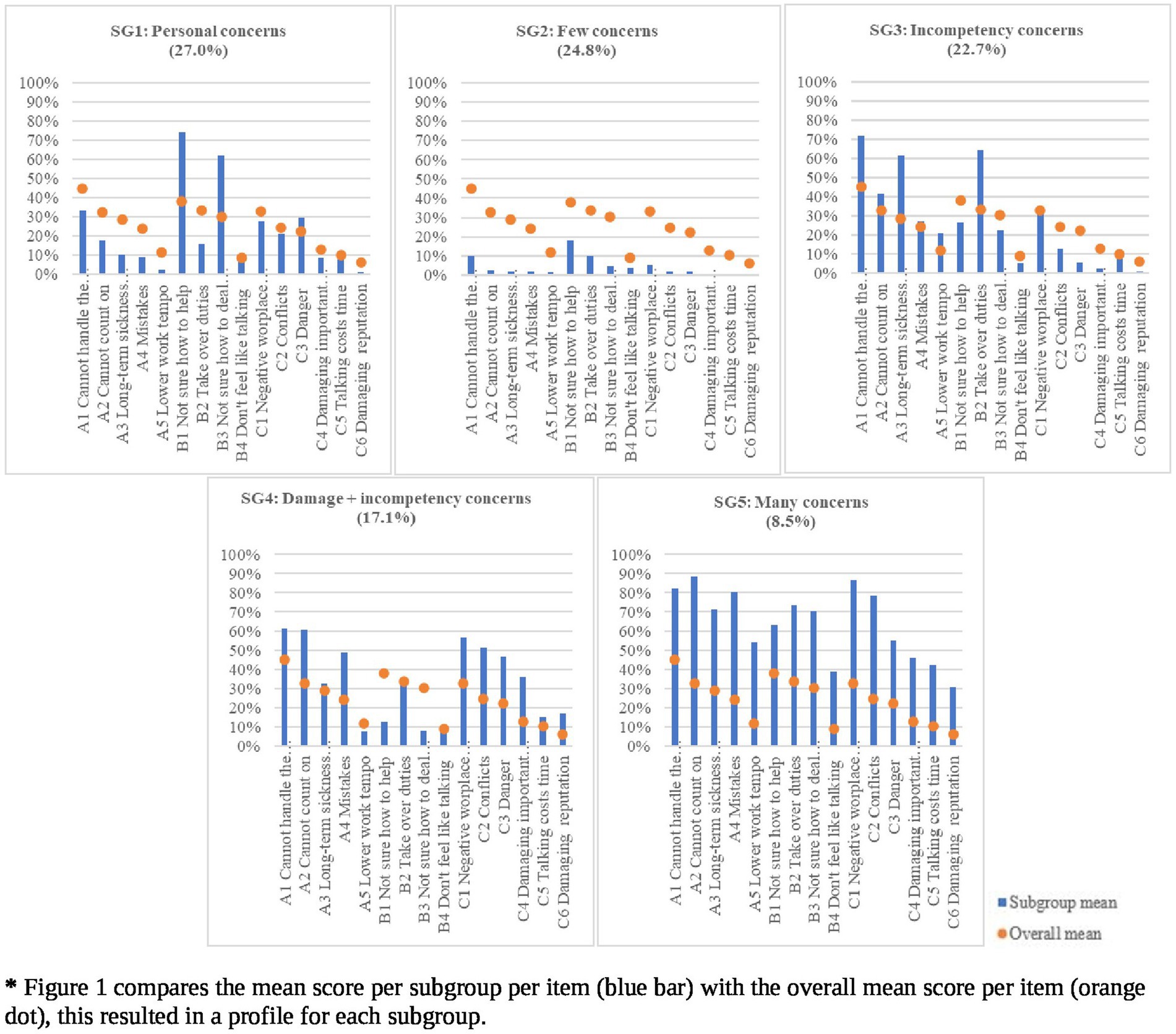

Figure 1 presents the five subgroups of respondents and their concerns about having a coworker with MHI. Significant differences between the subgroups were found on all the concerns. Respondents in the few concerns subgroup (SG2) have very few concerns about having a coworker with MHI (24.8% of the sample). Respondents in the personal concerns subgroup (SG1), which is the biggest subgroup (27.0% of the sample), have also low probabilities on most concerns, but are concerned about how they can help and deal with a coworker with MHI. Respondents in the incompetency concerns subgroup (SG3), have average probabilities on most concerns, but do have concerns that the coworker would be incompetent (22.7% of the sample). Respondents in the damage and incompetency concerns subgroup (SG4), have incompetency concerns and they are also concerned about damage to the workplace, but they have few concerns about how to help and deal with coworkers with MHI (17.1% of the sample). Respondents in the many concerns subgroup (SG5), the smallest subgroup (8.5% of the sample), have the highest probabilities on almost all concerns.

Figure 1. Profiles of the five subgroups based on potential concerns about having a coworker with MHI.

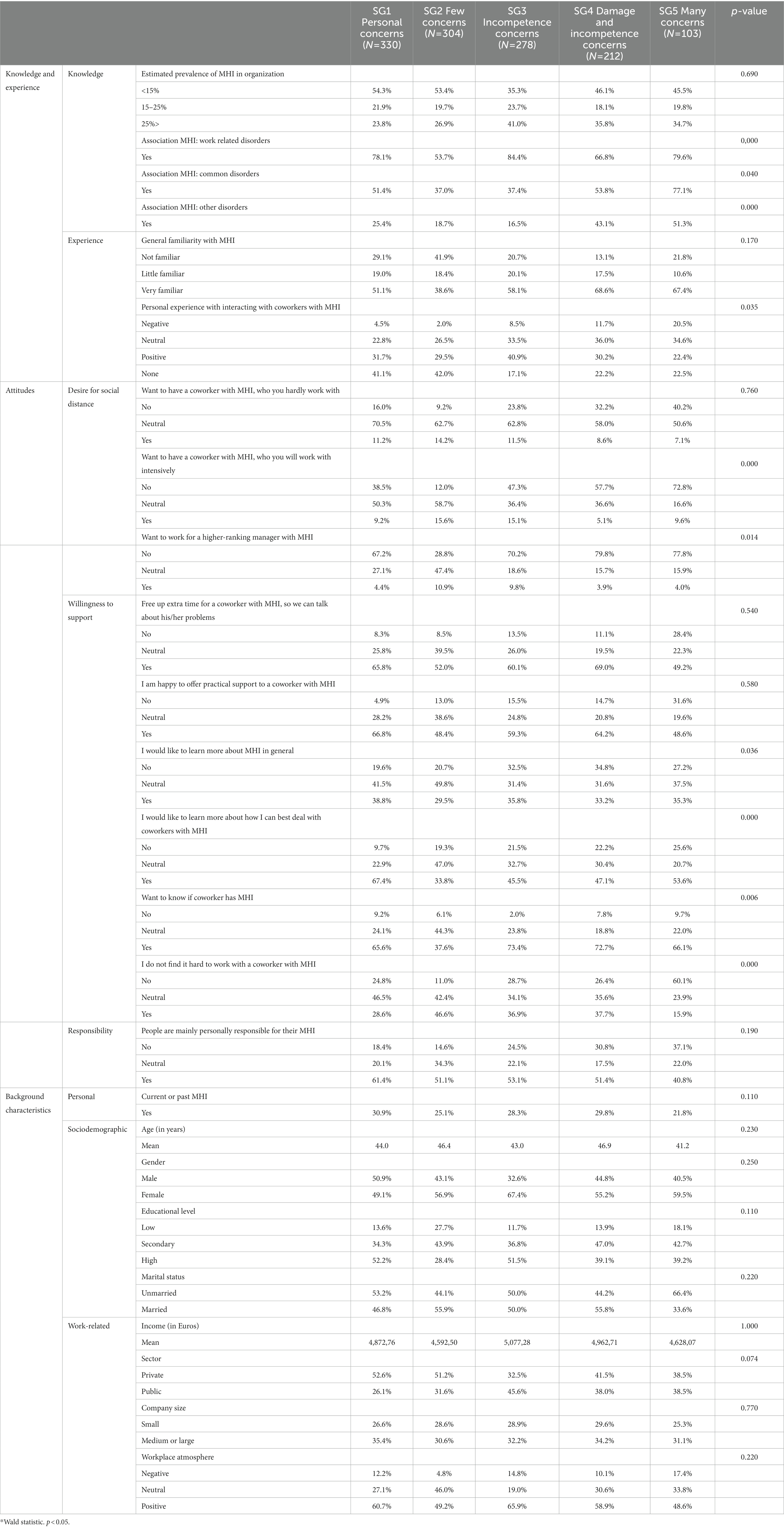

Respondents in the few concerns subgroup (SG2), i.e., with overall few concerns about having a coworker with MHI, scored the lowest on all the social distance items (ranging from 12.2% for not wanting to work with a coworker with MHI who they work intensively with to 28.8% not wanting to work for a higher ranking manager with MHI). SG2 contained the least respondents who were negative about wanting to have a coworker with MHI who they would have to work with intensively (12.0%), and the least respondents who were negative about wanting to work for a higher-ranking manager with MHI (28.8%). In SG2 the workers most often had no personal experience with interacting with coworkers with MHI (42.0%) (See Table 4).

Table 4. Characteristics of the subgroups in terms of knowledge, experience, attitudes, and background variables.

The respondents in the personal concerns subgroup (SG1), i.e., with overall few concerns but with concerns about how they can help and deal with a coworker with MHI, scored much higher on the social distance items compared to SG2 (ranging from 38.5% for not wanting to work with a coworker with MHI who they work intensively with to 67.2% not wanting to work for a higher ranking manager with MHI). In SG1 the respondents were slightly more often willing to like to learn more about MHI in general (38.8%) compared to other subgroups, but still, they rather preferred to learn more about how they could best deal with coworkers with MHI (67.4%). SG1 contained relatively more respondents with no personal experience with interacting with coworkers with MHI (41.1%) compared to the other subgroups.

The incompetency concerns subgroup (SG3), i.e., with average score on most concerns but with concerns about possible incompetency of the coworker with MHI, Compared to SG1 and SG2, contained more respondents who scored high on the social distance items (ranging from 47.3% for not wanting to work with a coworker with MHI who they work intensively with to 70.2% not wanting to work for a higher ranking manager with MHI). Almost half of SG3 would like to learn more about how they could best deal with coworkers with MHI (45.5%). SG3 differentiated from the other subgroups by containing the most respondents who had positive experiences with interacting with coworkers with MHI (40.9%).

The respondents in the damage and incompetency concerns subgroup (SG4), i.e., with slightly more concerns and specifically concerns on incompetency and also damage to themselves and the workplace, compared to the SG1, SG2, and SG3, contained relatively more respondents who scored high on the social distance items (ranging from 57.7% for not wanting to work with a coworker with MHI who they work intensively with to 79.8% not wanting to work for a higher ranking manager with MHI). Just like SG3, almost half of SG3 would like to learn more about how they could best deal with coworkers with MHI (47.1%). Respondents from SG4 were more likely to associate a coworker with MHI with other (more severe) disorders (43.1%) compared to the other subgroups.

The many concerns subgroup (SG5), i.e., with overall a lot of concerns, compared to the other subgroups, contained the most respondents who scored high on the social distance items (ranging from 72.8% for not wanting to work with a coworker with MHI who they work intensively with to 77.8% not wanting to work for a higher ranking manager with MHI). Respondents in this subgroup found it much harder to work with a coworker with MHI (60.1%), compared to the other subgroups. Around half of SG5 would like to learn more about how they could best deal with coworkers with MHI (53.6%). SG5 contained most respondents who associated a coworker with MHI other (more severe) disorders (51.3%), and the most respondents, but still a relatively small percentage, with a negative experience with interacting with coworkers with MHI (20.5%).

The aims of this study were to examine (1) Dutch workers’ knowledge and attitudes towards having a coworker with MHI, especially concerning the desire for social distance, (2) to identify distinct subgroups of workers based on their potential concerns towards having a coworker with MHI, and (3) to characterize these subgroups in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and background characteristics. First, concerning the desire for social distance, nearly half of the respondents did not want to have a coworker with MHI who they would have to work with intensively and about two-thirds did not want to work for a higher-ranking manager who had MHI. Almost half of the respondents showed willingness to learn more about how to communicate and deal with coworkers with MHI. Very few workers had negative personal experiences with interacting with coworkers with MHI. The most frequently reported concern was that a coworker with MHI would not be able to handle the work. For the second research aim, five distinct subgroups of respondents were identified based on their concerns about having a coworker with MHI: two subgroups with few concerns (SG1 and SG2), one subgroup with average concerns (SG3), and two subgroups with more concerns (SG4 and SG5). Third, these subgroups were characterized by significant differences in knowledge, experience, and attitudes. Four out of five subgroups showed a high tendency towards the desire for social distance. Even in the subgroups with average and more concerns (almost) half of the respondents were willing to learn more about how to best deal with coworkers with MHI. The subgroups with more concerns contained most respondents who associated a coworker with MHI with other (more severe) disorders. No significant differences were found between the subgroups on background characteristics.

This study showed overall a high tendency towards the desire for social distance. When differentiated in subgroups, even higher rates were found for the subgroups with average or more concerns. This is worrying, and in line with previous research which reported that respondents did not want to work with or for people with MHI due to stigma (11). As 92.6% did not have negative personal experiences with interacting with coworkers with MHI, this tendency to the desire for social distance is not likely to be based on personal experiences. Our analyses showed that even in the subgroup with the most concerns (SG5) only 20.5% of the respondents had actual negative experiences with interacting with coworkers with MHI in the workplace. Moreover, the tendency towards exclusion without having negative experiences was also found in a study among Dutch line managers, where 64% was reluctant to hire a job applicant with a mental health issue, despite the fact that only 7% of them had actual negative experiences with such workers (6). Also, it is noteworthy that this present study showed that the tendency towards the desire for social distance is higher when respondents were asked about having to work for a higher-ranking manager with MHI compared to having to work with a coworker with MHI. A qualitative study also showed that negative disclosure outcomes were more likely to be expected for people with MHI in higher positions (1). More research is needed to understand this difference. The results concerning the high tendency towards the desire for social distance underline the importance of an adequately prepared disclosure decision. The high desire for social distance towards coworkers with MHI might also be partly due to the Dutch context. The Extended Payment of Income Act states that employers pay at least 70% of the income for the first 2 years of sickness absence. This might create an incentive for employers to be more careful during the hiring process, which can stimulate a culture of social distancing and exclusion.

To design an effective intervention it is important to understand what the focus needs to be, as stigma has three dimensions the focus can be on problems of: knowledge (misinformation or ignorance), attitudes (prejudice), and behaviour (discrimination) (21). Anti-stigma interventions in the workplace like increasing knowledge can lead to helping behaviour mediated by the change in attitudes, since these three dimensions are interrelated (15). This present study indicates that anti-stigma interventions in the workplace should focus on increasing knowledge, as there was a need among respondents to learn how to best deal with coworkers with MHI and to learn more about MHI in general. As the present study found no differences in background characteristics between the subgroups, this indicates that anti-stigma interventions in the workplace do not need to differentiate in background variables of workers.

A strength of this study is the use of a large representative sample of Dutch workers. The workers were selected from population registers based on a true probability sample and participated anonymous to prevent the respondents’ possible tendency to underreport socially undesirable responses and overreport more socially desirable responses. Furthermore, this is one of the first datasets that focuses on workplace stigma in Netherlands which provides important new insights in the attitudes of workers. Another strength is that in this study coworkers were not seen as one homogenous group, but that heterogeneity was taken into account reflecting individual differences better which is needed for designing interventions. Latent Class Analysis, an increasingly popular method, is strong in identifying subgroups and it uses a model-based technique which enables researchers to have more flexibility and accuracy when looking into the subgroups and the associated variables (34). Although this study generated valuable insights, there are a few limitations. Self-reported data were used which were based on perceptions, rather than on actual behaviour. Nevertheless, perceptions have been linked to actual behaviour (35). Additionally, this study focused on concerns, which might reflect a more negative view of the reality because this study did not simultaneously focus on positive attitudes. Future studies should also focus on the positive attitudes in order to add more knowledge on both the positive and negative attitudes towards coworkers with MHI, because knowledge about such attitudes may also be helpful in designing interventions to create more inclusive workplaces.

This representative sample of Dutch workers showed a high tendency towards the desire for social distance of coworkers with MHI. As much as 41.9% did not want to have a coworker with MHI who they would work with intensively. The desire for social distance was even much higher towards managers with MHI: 64.1% did not want to work for a higher-ranking manager with MHI. Interestingly, despite these high percentages, over 92.6% of workers did not personally have negative experiences with interacting with coworkers with MHI. Workers differed in their concerns about having a coworker with MHI, five distinct subgroups were identified. Differences between these subgroups were found in knowledge, experience, and attitudes towards having a coworker with MHI. This study found that anti-stigma interventions in the workplace which focus on increasing knowledge are needed. This study found that anti-stigma interventions in the workplace which focus on increasing knowledge are needed, because (almost) half of the workers indicated they would like to learn more about MHI. These interventions should especially focus on increasing the knowledge of workers about how to best communicate and deal with coworkers with MHI and about MHI in general in order to create more inclusive workplaces to improve sustained employment of people with MHI.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Ethics Review Board of the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences of Tilburg University (registration number: RP606). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

EB, MB, MJ, GS, and IB designed the study. MB assisted IB with the statistical analysis of the study. IB and GS wrote the manuscript. EB, MB, MJ, GS, CD, JW, and CH contributed to reviewing and revising of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by the Tilburg University Alumni Fund.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1212568/full#supplementary-material

1. Brouwers, E , Joosen, M , van Zelst, C , and van Weeghel, J . To disclose or not to disclose: a multi-stakeholder focus group study on mental health issues in the work environment. J Occup Rehabil. (2020) 30:84–92. doi: 10.1007/s10926-019-09848-z

2. Hipes, C , Lucas, J , Phelan, JC , and White, RCJSSR . The stigma of mental illness in the labor market. Soc Sci Res. (2016) 56:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.12.001

3. Thornicroft, G , Rose, D , Kassam, A , and Sartorius, N . Stigma: ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? Psychiatry. (2007) 190:192–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791

4. EPJBP, B. Social stigma is an underestimated contributing factor to unemployment in people with mental illness or mental health issues: position paper and future directions. BMC Psychol. (2020) 8:36–7. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-00399-0

5. Brouwers, E , Mathijssen, J , Van Bortel, T , Knifton, L , Wahlbeck, K , Van Audenhove, C, et al. Discrimination in the workplace, reported by people with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study in 35 countries. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e009961. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009961

6. Janssens, KM , van Weeghel, J , Dewa, C , Henderson, C , Mathijssen, JJ , Joosen, MC, et al. Line managers’ hiring intentions regarding people with mental health problems: a cross-sectional study on workplace stigma. Occup Environ Med. (2021) 78:593–9. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-106955

7. van Beukering, I , Bakker, M , Corrigan, P , Gürbüz, S , Bogaers, R , Janssens, K, et al. Expectations of mental illness disclosure outcomes in the work context: a cross-sectional study among Dutch workers. J Occup Rehabil. (2022) 32:652–63. doi: 10.1007/s10926-022-10026-x

8. ten Have, M , Tuithof, M , van Dorsselaer, S , Schouten, F , and de Graaf, RNEMESIS . Kerncijfers psychische aandoeningen samenvatting. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut (2022).

9. van Beukering, I , Smits, S , Janssens, K , Bogaers, R , Joosen, M , Bakker, M, et al. In what ways does health related stigma affect sustainable employment and well-being at work? A systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. (2021) 32:365–79. doi: 10.1007/s10926-021-09998-z

10. HJCOIP, S. Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr Opin Psychiatr. (2006) 19:522–6. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000238482.27270.5d

11. Russinova, Z , Griffin, S , Bloch, P , Wewiorski, NJ , and Rosoklija, I . Workplace prejudice and discrimination toward individuals with mental illnesses. J Vocat Rehabil. (2011) 35:227–41. doi: 10.3233/JVR-2011-0574

12. Rüsch, N , Rose, C , Holzhausen, F , Mulfinger, N , Krumm, S , Corrigan, PW, et al. Attitudes towards disclosing a mental illness among German soldiers and their comrades. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 258:200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.028

13. Dalgin, RS , and DJPRJ, G . Perspectives of people with psychiatric disabilities on employment disclosure. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2003) 26:306–10. doi: 10.2975/26.2003.306.310

14. Dobson, KS , Szeto, A , and Knaak, S . The working mind: a meta-analysis of a workplace mental health and stigma reduction program. Can J Psychiatr. (2019) 64:39S–47S. doi: 10.1177/0706743719842559

15. Hanisch, SE , Twomey, CD , Szeto, AC , Birner, UW , Nowak, D , and CJBP, S . The effectiveness of interventions targeting the stigma of mental illness at the workplace: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0706-4

17. Javed, A , Lee, C , Zakaria, H , Buenaventura, RD , Cetkovich-Bakmas, M , Duailibi, K, et al. Reducing the stigma of mental health disorders with a focus on low-and middle-income countries. Asian J Psychiatr. (2021) 58:102601. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102601

18. Krendl, AC , and Pescosolido, BA . Countries and cultural differences in the stigma of mental illness: the east–west divide. J Cross-Cult Psychol. (2020) 51:149–67. doi: 10.1177/0022022119901297

19. Bogaers, R , Geuze, E , van Weeghel, J , Leijten, F , van de Mheen, D , Varis, P, et al. Barriers and facilitators for treatment-seeking for mental health conditions and substance misuse: multi-perspective focus group study within the military. BJPsych open. (2020) 6:e146. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.136

20. Bogaers, R , Geuze, E , van Weeghel, J , Leijten, F , Rüsch, N , van de Mheen, D, et al. Decision (not) to disclose mental health conditions or substance abuse in the work environment: a multiperspective focus group study within the military. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e049370. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049370

21. Henderson, C , Williams, P , Little, K , and Thornicroft, G . Mental health problems in the workplace: changes in employers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices in England 2006–2010. Br J Psychiatry. (2013) 202:s70–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112938

22. Brohan, E , Henderson, C , Wheat, K , Malcolm, E , Clement, S , Barley, EA, et al. Systematic review of beliefs, behaviours and influencing factors associated with disclosure of a mental health problem in the workplace. BMC Psychiatry. (2012) 12:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-11

23. Hooftman, W , Mars, G , and van Dam, L . Nationale Enquete arbeidsomstandigheden 2019 [Netherlands working conditions survey 2019]. Leiden, Netherlands: TNO (Google Scholar) (2020).

24. Holmes, EP , Corrigan, PW , Williams, P , Canar, J , and Kubiak, MA . Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1999) 25:447–56. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033392

25. Brohan, E , Evans-Lacko, S , Henderson, C , Murray, J , Slade, M , Thornicroft, GJE, et al. Disclosure of a mental health problem in the employment context: qualitative study of beliefs and experiences. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2014) 23:289–300. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000310

26. TLJIjol, S. Stigma as a barrier to employment: mental disability and the Americans with disabilities act. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2005) 28:670–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.04.003

27. Jones, AM. Disclosure of mental illness in the workplace: a literature review. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2011) 14:212–29. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2011.598101

28. Gignac, MA , Jetha, A , Ginis, KAM , and Ibrahim, S . Does it matter what your reasons are when deciding to disclose (or not disclose) a disability at work? The association of workers’ approach and avoidance goals with perceived positive and negative workplace outcomes. J Occup Rehabil. (2021) 31:638–51. doi: 10.1007/s10926-020-09956-1

29. Nylund, KL , Asparouhov, T , and Muthén, BO . Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. (2007) 14:535–69. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396

30. Langeheine, R , Pannekoek, J , and Van de Pol, F . Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in categorical data analysis. Sociol Methods Res. (1996) 24:492–516. doi: 10.1177/0049124196024004004

31. Nasserinejad, K , van Rosmalen, J , de Kort, W , and Lesaffre, E . Comparison of criteria for choosing the number of classes in Bayesian finite mixture models. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0168838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168838

32. Vermunt, JK , and Magidson, J . Technical guide for latent GOLD 5.0: Basic, advanced, and syntax. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations Inc (2013).

33. Vermunt, JK , and Magidson, J . Upgrade manual for latent GOLD basic, advanced, syntax, and choice version 6.0 Statistical Innovations Inc Arlington, M.A. (2021).

34. Petersen, KJ , Qualter, P , and Humphrey, N . The application of latent class analysis for investigating population child mental health: a systematic review. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:1214. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01214

Keywords: mental health, stigma, discrimination, workplace, coworker

Citation: van Beukering IE, Sampogna G, Bakker M, Joosen MCW, Dewa CS, van Weeghel J, Henderson C and Brouwers EPM (2023) Dutch workers’ attitudes towards having a coworker with mental health issues or illness: a latent class analysis. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1212568. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1212568

Received: 26 April 2023; Accepted: 21 June 2023;

Published: 10 July 2023.

Edited by:

Abdrabo Moghazy Soliman, Qatar University, QatarReviewed by:

Filippo Rapisarda, Consultant, Montreal, CanadaCopyright © 2023 van Beukering, Sampogna, Bakker, Joosen, Dewa, van Weeghel, Henderson and Brouwers. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: I. E. van Beukering, aS5lLnZhbmJldWtlcmluZ0B0aWxidXJndW5pdmVyc2l0eS5lZHU=

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.