95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 19 May 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1183234

This article is part of the Research Topic Community Series in Mental Illness, Culture, and Society: Dealing with the COVID-19 Pandemic, Volume VI View all 10 articles

Shahana Ayub1

Shahana Ayub1 Gibson O. Anugwom2

Gibson O. Anugwom2 Tajudeen Basiru3

Tajudeen Basiru3 Vishi Sachdeva4

Vishi Sachdeva4 Nazar Muhammad1

Nazar Muhammad1 Anil Bachu5

Anil Bachu5 Maxwell Trudeau6

Maxwell Trudeau6 Gazal Gulati6

Gazal Gulati6 Amanda Sullivan7

Amanda Sullivan7 Saeed Ahmed8

Saeed Ahmed8 Lakshit Jain6,7,9*

Lakshit Jain6,7,9*Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has had global impacts on social interactions and religious activities, leading to a complex relationship between religion and public health policies. This article reviews impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on religious activities and beliefs in relation to the spread of the virus, as well as the potential of religious leaders and faith communities in mitigating the impact of the pandemic through public health measures and community engagement.

Methods: A literature review was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar, with search terms including “religion,” “COVID-19,” “pandemic,” “coronavirus,” and “spirituality.” We included English articles published between January 2020 and September 2022, focusing on intersection of religion and COVID-19.

Results: We identified two main themes emerging, with the selected 32 studies divided in 15 studies focused on the relationship between religious practices, beliefs, and the spread of COVID-19, while 17 studies explored the role of religious leaders and faith communities in coping with and mitigating the impact of COVID-19. Religious activities were found to correlate with virus spread, particularly in early days of the pandemic. The relationship between religiosity and adherence to government guidelines was mixed, with some studies suggesting increased religiosity contributed to misconceptions about the virus and resistance to restrictions. Religious beliefs were also associated with vaccine hesitancy, particularly conservative religious beliefs. On the other hand, religious leaders and communities played a crucial role in adapting to COVID-19 measures, maintaining a sense of belonging, fostering emotional resilience, and upholding compliance with public health measures. The importance of collaboration between religious leaders, institutions, and public health officials in addressing the pandemic was emphasized.

Conclusions: This review highlights the essential role of religious leaders, faith-based organizations, and faith communities in promoting education, preparedness, and response efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Engaging with religious leaders and communities can improve pandemic control and prevention efforts. Collaboration between religious leaders, governments, and healthcare professionals is necessary to combat vaccine hesitancy and ensure successful COVID-19 vaccination campaigns. The insights from this review can guide future research, policy development, and public health interventions to minimize the impact of the pandemic and improve outcomes for individuals and communities affected.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted nearly every aspect of our lives, its implications even reaching our religious activities, which remains an important topic of debate and ongoing research ranging from social distancing at religion functions to vaccination acceptance among congregations. A significant toll has been taken on traditional human connections such as these, and this has forced all stakeholders to adopt innovative approaches to address religious gatherings' emergent issues. Whether holding virtual meetings or deploying contact tracing apps, individuals and organizations alike have adopted creative ways to continue communing with one another while trying to keep the risk of transmission low. Historically, religion has served a crucial role in shaping public health outcomes during times of crisis—consider the Ebola epidemic, pandemic influenza, and ongoing worldwide health concerns such as HIV/AIDS (1). Indeed, religion's influence has appeared before us in beneficial, and at times, detrimental ways during these emergencies (1, 2). Positive and negative impacts have stemmed from religious gatherings and rituals due to the extent which religious leaders have adhered to established guidelines. In the case of COVID-19, while some religious groups have been praised for their adherence to public health precautions, others have received criticism for disregarding limitations and thus contributing to the virus's spread. This latest pandemic highlighted the role of religious institutions and practices in either curbing or accelerating viral spread, as well as their contribution to public health efforts to control previous pandemics, such as the Spanish flu and H1N1.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to changes in religious practices and rituals, with some communities resisting or outright defying restrictions suggested by their national or local governments or scientific communities. In turn, this had the negative effect of contributing to viral spread. Unfortunately, these negative cases pitted religion against evidence-based science, with the former seeing its adherents clinging to their religious faith for protection instead of listening to scientific advice (1). Meanwhile, in the positive sense, other religious communities successfully followed both religious guidance and scientific recommendations to reduce the risk of viral spread.

To better understand the interplay of religion and public health amid the COVID-19 pandemic, several global studies have explored the ways religion has influenced individuals and communities during this crisis. One study revealed how the pandemic forced religious leaders to redesign mosque worship and how Muslims adapted their practices (3). Another study in Israel revealed how ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities experienced a significantly higher rate of COVID-19 infections due to factors such as overcrowding, distrust of state authorities, and resistance to social-distancing orders. The rapid spread of the virus in such religious communities increased tensions and raised questions about the balance between religious practice and public health (4).

Studies from global regions as diverse as Ghana, Poland, and Malaysia have explored the impact of COVID-19 on religious communities, psychospiritual gatherings, and other religious practices; as well as the role of religious expression in coping with pandemic-derived stress. In Ghana, Osei-Tutu et al. (5) explored religious leaders' views on the impact of COVID-19 as it related to restrictions placed on their congregants' wellbeing. The study found that people suffered a plethora of psychospiritual effects due to the pandemic, such as a decline in spiritual life, a sense of loss of fellowship and community, financial difficulties, anxiety over childcare, and fear of infection (5). Osei-Tutu's study revealed how religious leaders positively intervened by delivering sermons on hope, faith, and repentance, with some going so far as to sensitize their membership to topics such as health hygiene and COVID-19-related stigma. In Poland, Sulkowski et al. (6) investigated the impact of the pandemic on that country's religious life, finding that some churches either limited or entirely suspended their traditional community-based religious life in light of the pandemic, seeking to reduce risk of viral spread while maintaining contact with and among believers via modern technology (6). A Malaysian study by Ting et al. (7) investigated several pandemic-related variables, such as illness perception, stress levels, and religious expressions of major religious groups (7). Ting et al. (7) study notably reported that religious expression carried a negative relationship with stress levels, highlighting the importance of religion's role in shaping responses to public-health emergencies, particularly in communities where religion serve a significant role in people's lives. Taken together, these studies confirm the important, even primary role religion can play in shaping responses to public health emergencies (5–7).

Researchers from other countries such as Colombia, South Africa, and the United States, have examined the roles of hope, religious coping, and community organizations in promoting wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Counted et al. (8) examined these roles and their wellbeing effects in Colombia and South Africa, revealing that hope was positively associated with wellbeing and that the relationship between hope and wellbeing was itself moderated by religious coping. When hope was low, the researchers found, wellbeing trended higher when positive religious coping was high and negative religious coping was low (8). This study highlights the importance of considering the role of religious leaders and their support in addressing the psychospiritual impacts of the pandemic, particularly in communities where religion plays a significant role in people's lives, as other studies have concluded. In the United States, Weinberger-Litman's (9) study examined anxiety and distress among members of the first community in the USA to be quarantined due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a community of Orthodox Jews (9). The study found that community organizations were trusted more than any other source of COVID-19-related information and played a vital role in promoting the wellbeing of their constituents by organizing support mechanisms such as the provision of tangible needs, social support, virtual religious services, and dissemination of virus-related health information. In their conclusions, these studies supported the findings of the mentioned prior ones (8, 9).

Similar studies conducted in Portugal, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and New Zealand have explored the roles of spiritual-religious coping, religious freedom restrictions, and worship adaptations during the COVID-19 pandemic (10–12). Prazeres et al. (11) examined the impact of spiritual-religious coping on fear and anxiety related to COVID-19 in Portugal's healthcare workers, finding that religiosity was not a significant factor in reducing coronavirus-related anxiety, and that higher levels of hope and optimism along the spirituality scale were associated with less anxiety (11). Begović (10) found that religious communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina displayed varying responses to pandemic restrictions on religious freedom imposed by state regulations (10). Here, some communities willingly agreed to the restrictions placed on their religious guidelines and practices, while others struggled to agree. Despite their differences, the researcher found, all communities were able to find support in their religious laws and theological views, which emphasized the value of human life and the importance of caring for their community's wellbeing (10). In New Zealand, Oxholm (12) reported that the COVID-19 pandemic caused religious communities to review their worship practices and prioritize community welfare and pastoral care for the elderly and vulnerable (12). To that end, congregations shifted to virtual worship. In this case, the challenges of mitigating transmission risk, social distancing, and providing welfare overlapped (12).

COVID-19 indeed caused significant global upheaval, leading to quarantines and a rising death toll. With healthcare professionals plying science to control the virus, religious organizations and psychospiritual groups provided solace while, with a few exceptions, also contributing to the recommended protective measures, such as social distancing and the cancellation or conversion of large gatherings in some faiths (13). The exceptions included the Islamic State, which regarded the pandemic as divine retribution; and Feng shui practitioners, who attributed it to an imbalance of elements in the Year of the Rat (14). It remains notable that major religious gatherings were identified as significant clusters of viral spread in Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea (14).

For complying religious groups, the pandemic prompted a transition from in-person religious communities to virtual congregations, challenging conventional notions of belonging and participation (15), This transformation required embracing digital platforms for live-streaming of services, Zoom baptisms, and Skype confessions, etc. (15, 16) while less-compliant religious groups resisted change. Additionally, religious leaders here offered explanations and comfort to their congregations during uncertain times, highlighting the resurgence of religion and spirituality in the face of a global crisis (14).

A survey study by Seryczynska et al. (17) explored the role of religious capital in coping during the COVID-19 pandemic in four European countries: Spain, Italy, Poland, and Finland. Their results revealed that religious capital indeed can impact individuals' coping strategies, but its dynamics, the ways it does so, are complex (17). This survey's results provide a better understanding of the role of religious capital in helping people cope with harsh circumstances.

While the scientific community has largely come together in controlling the spread of the coronavirus, primarily through advising mask wearing, social distancing, and developing vaccines, its pandemic-curtailing efforts have been hampered by various factors, oftentimes religious gatherings. Such gatherings provide an essential role in society, but governments, the scientific community, and healthcare entities worldwide have experienced pushback from certain religious entities regarding their advised pandemic-response measures.

The present paper reviews the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on lives around the world, including the responses by the respective public health authorities, the associated factors that dictated the outcome of those responses, and the implications of the intertwined nature of religion, public-health policy, and social responsibility. The researchers subsequently investigate two main intersections where religion met public health during the COVID-19 pandemic: first, the connections between religious practices, beliefs, and the spread of the virus, including both the positive and negative consequences of religious activities; and second, the role of religious leaders and faith communities in coping with and mitigating the impact of COVID-19. In doing so, we hope to offer a unique multidisciplinary perspective on the complex interplay between religious practices and public-health outcomes, emphasizing the importance of taking a balanced, holistic approach to mitigating—or preventing—public health crises. By synthesizing this intersectional area's existing research, we can not only contribute to the related literature by providing a better understanding of the intersection of religion and public health crises, but also identify any potential gaps warranting future research.

We conducted a structured and systematic literature search on PubMed and Google Scholar using keywords such as “religion,” “COVID-19,” “pandemic,” “coronavirus,” and “spirituality” to study the intersection of religion and the COVID-19 pandemic. Our search was conducted from January 2020 to March 2023. We included peer-reviewed articles, published in English language, primarily observational studies, cross-sectional studies, surveys, and systematic reviews. We excluded case reports, case series, non-English papers, papers not directly related to the topic, papers with data that was difficult to extract, and unpublished papers. The articles must focus on one or both of the following aims: investigating connections between religious practices, beliefs, and the spread of the COVID-19 virus, including both the positive and negative consequences of religious activities; and exploring the role of religious leaders and faith communities in coping with and mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Initially, we identified 2,256 papers through our search strategy, which we then narrowed down to 876 by removing duplicates. After screening the titles of these papers, we included 327 citations for abstract screening. During abstract screening, we excluded 549 citations based on our inclusion criteria, which focused on studies that provided insights into the role of religion and religious activities in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The remaining 122 papers were reviewed for eligibility by SA and LJ, and any disagreements were mediated by a third reviewer (SA). Additionally, we employed a snowballing technique whereby we identified and selected review articles on our topic of interest (1, 13, 18–20), and then used their reference lists to further identify relevant studies. This approach helped us to expand our search results and ensure that we did not miss any important studies that were relevant to our topic. We have included a study selection flow diagram (Figure 1) to illustrate the process of identifying, screening, and selecting articles for our review. This diagram provides a transparent representation of our literature search and selection process.

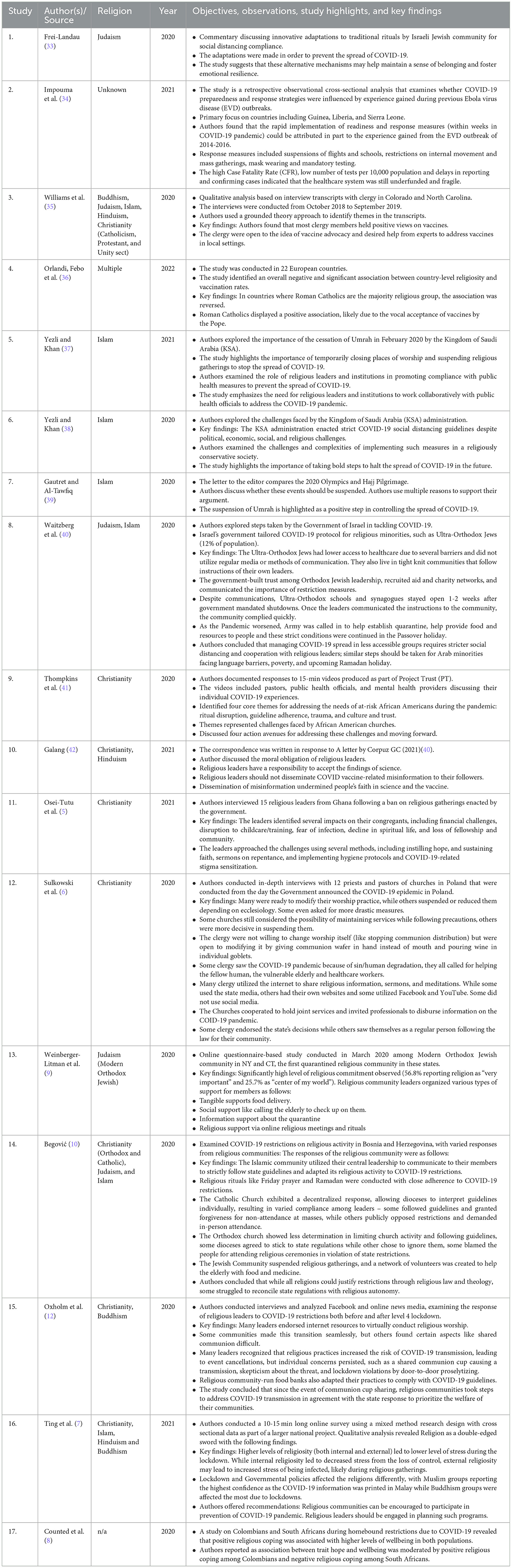

32 full-text articles were identified that met our inclusion criteria for this literature review. We categorized these articles into two tables based on their focus: Table 1, which captures studies investigating the relationship between religious practices, beliefs, and the spread of COVID-19, and Table 2, which explores the role of religious leaders and faith communities in coping with and mitigating the impact of the pandemic. We acknowledge that the studies included in our review come from various research designs, and our aim was to provide a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on the topic rather than a strict synthesis of the findings.

Table 2. Exploring the role of religious leaders and faith communities in coping with and mitigating the impact of COVID-19.

The role of religious gatherings, ceremonies, and practices in contributing to the spread of COVID-19 has been noted in published literature. Researchers reported that these types of events played a significant role particularly in the pandemic's early days (1, 22–24). Though a strong correlation existed between religious activities and viral spread, it is worth noting that the study by Lee et al. (1) emphasized that religious activity could both accelerate and mitigate COVID-19. This illustrates religion's dual potential effects on public health crises. The relationship between religiosity that adhered with guidelines recommended or mandated by various government remains unclear. Some studies have found people in more religious areas or with higher levels of religiosity were less likely to comply with social distancing and stay-at-home orders (27, 32). Other studies have found some correlation between increased religiosity and misconceptions about the virus, as well as resistance to government mandated restrictions (28).

Regarding vaccination acceptance, religious beliefs had association with vaccine hesitancy, particularly when conservative religious beliefs linked with skepticism toward vaccines and overall public-health initiatives (1, 29).

The pandemic saw various religious leaders from various countries facing unique challenges in caring for their communities. Studies showed that effective communication and collaboration with public-health authorities or local governments remained vital in promoting adherence to guidelines and dismantling misinformation (3, 26, 43). The pandemic has also caused changes in religious practices. While some individuals have turned to religion for comfort and support during these uncertain times, others have experienced a crisis of faith or questioned their beliefs (14, 28).

Given the mixed findings on the relationship between religiosity and compliance with COVID-19 guidelines, it is important for researchers to continue examining it.

The published literature shows the impact of the pandemic on various religious communities and the challenges they faced, whether financial, childcare disruption, fear of infection, or loss of fellowship (5, 41).

Several studies revealed the importance of religious leaders and communities adapting to COVID-19 measures to maintain a sense of belonging and foster emotional resilience among their congregations (33, 35, 37). Some studies highlight how religious communities adjusted their traditional religious ritual and practices, ultimately complying with social distancing guidelines and safety measures to prevent viral spread (6, 12, 36). Other studies revealed the importance of collaboration between religious leaders, institutions, and public health officials in addressing the pandemic (37, 42). Still others revealed the important role religious leaders and institutions have played in upholding compliance with public-health measures and providing various support services (9, 10). Overall, most published studies underscore the need for religious leaders to accept scientific findings and resist disseminating COVID-19 and vaccine-related misinformation (42).

The evaluated studies highlight the complex relationship between religion, religiosity, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Religious gatherings and activities played significant roles in the spread of COVID-19 across the world, as evidenced by the reviewed published studies (1, 3, 22–25, 27, 29–32). The literature shows the role of religious activity in amplifying the spread of COVID-19, through non-wearing of masks, non-adherence to social distancing, and at times through the promotion of misinformation. While some studies have suggested religion as a risk factor for contracting COVID-19; other studies identify religion as a positive source of coping and resilience (1, 26, 32).

The ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic led to existential crises in many, with some religious believers finding meaning by leaning into apocalyptic narratives, which some of the secular also did (20). Viewing the pandemic as an act of a superior being, certain religious leaders and organizations refused to change their group rituals and ceremonies. Several pastors expressed the belief that only God would decide when someone died and not the government, and thus refused to stop holding packed church services (44). Such religious defiance and harmful-belief promotion ultimately led to a rejection of government recommended or mandated COVID-19 guidelines, increasing the virus's transmission among the masses (1, 3, 27, 28).

In certain instances, both governments and religious leaders have been criticized for their handling of the pandemic. For example, during the second wave of COVID-19 infections in April 2021 in India, the decision to continue with the annual Kumbh Mela, a pilgrimage that attracts over nine million people, was deemed irresponsible by some public health experts. Despite concerns raised regarding the potential spread of the virus, minimal precautions were taken, and pandemic guidelines were not strictly enforced. These included a lack of social distancing and wearing masks. Such actions have been viewed by some as further contributing to the crisis (21). This led to what some have called as a “massive superspreader event” (45). Unfortunately, no quarantine was enforced nor was contact tracing imposed on the returning pilgrims. This incident highlights how faith and distrust of science can lead to crisis (46). In the Middle East, similar incidents were reported, with increased spread associated in “Qom with Jewish and Shi'ite communities” with religious practices and travel to holy places of their respective countries (23).

In West Africa, the COVID-19 crisis was simply seen by the population as an extension of the Ebola crisis (34). What the Ebola crisis taught may have helped in managing the COVID-19 response, but persisting apocalyptic narratives here also played a role in viral spread (34). When COVID-19 reached Tanzania, that country's president stated that only faith in God and quack treatments like steam inhalation would defend them from COVID-19. He refused to enforce a lock down, and instead rubbished test kits, vaccines, and masking (47).

The pandemic placed many religious and psychospiritual communities in difficult positions, forcing them to make a difficult choice over whether to follow health regulations substantially, partly and not at all, and to keep pursuing their cultural norms, regarding funerals and other sanctified gatherings. In Brooklyn, New York's Hasidic Jewish community, doctors estimated that hundreds of Orthodox Jews died due to participating in super-spreading events such as funerals (48). Funeral restrictions also impacted other religions. Hindus, for example, who commonly cremate the bodies of loved ones in holy sites such as Varanasi, India, have had their travel restricted due to the pandemic. Culturally, these restrictions disrupted an important ritual, one that draws large families together in the throes of cathartic mourning (48). Here, tightly wrapping the bodies of victims of COVID-19 did prevent transmission, but also prevented the victim's families from saying their last goodbyes according to their religious beliefs (48).

Islamic cultures also experienced COVID-19 limitations to their tradition of burying their dead in a timely manner. In Iraq, burials were delayed for days, causing distress among the deceased's loved ones for their inability to provide a traditional funeral (48). The large number of coronavirus deaths also impeded funeral practices, since family members who were recently running from pillar to post to obtain scarce oxygen and a hospital bed, now had to struggle to secure burial plots or space in a funeral home to perform the final rites (49).

Some religious leaders, however, found creative solutions. For example, in the Jewish community, Rabbi Avraham Berkowitz decided to attend a family funeral (and set an example, perhaps) safely distanced in his car (50). Some priests started giving blessings from the hallway or over the telephone, while some funeral homes started drive-in funerals, with others reviving old traditions of bowing to a hearse when it passed by their home. Shivas were organized via video conference by the Jewish community, while Han Chinese live-streamed their tomb-sweeping ceremonies rather than visiting the tomb of their loved ones in person (51). A mixed method review by Burrell et al. (52) revealed that restrictions on funeral practices did not necessarily entail poor outcomes or experiences for the bereaved. Rather, they seemed to add meaning to the occasion and strengthened the connections mourners felt, as they played a much more critical role (52).

Despite these challenges, religious leaders have recognized their unique role in promoting healthy practices, communicating scientific information to their communities, and helping dispel myths and inaccuracies that contributed to the spread of COVID-19. Religious communities have had to encourage people to take precautions, accept vaccinations, adapt, and find innovative ways to continue their practices while minimizing the risk of infection (33, 35, 36, 39–42, 53).

Religion's skepticism over the COVID-19 vaccine coupled with the new technologies being used to practice religion gradually seemed to fade. More in-depth studies found the association between resistance and negative attitude toward vaccination most pronounced in religiously conservative communities (29, 35, 54).

Despite the myriad challenges, several examples appear where religious and community leaders issued guidance based on scientific recommendations and thus adapted their practices in response to the pandemic, changing the implications of these adaptations for public health outcomes. For example: The Catholic Church's Pope Francis loudly and globally professed support for the vaccine (42, 53). While countries with Roman Catholics as the majority religious group displayed a positive association between religiosity and vaccine rates (36). In some regions, religious leaders postponed religious events or utilized alternative modalities to maintain traditions and rituals in a COVID-friendly manner. In Saudi Arabia, the Muslim pilgrimage to the holy sites in the Kingdom were restricted, and a new e-Visa program was devised to ban inbound travel of persons from coronavirus-affected countries (37, 38, 55). In similar fashion, Jewish religious leaders adapted their manner of religious prayer by praying through a “balcony” minyan while conducting online havrutas using video conferencing, and virtually broadcasting Passover ceremonies (33). Programs such as Project Trust have helped religious leaders promote health in ways sensitive to their cultures and provided accurate information about public and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic (41).

The complex relationship between religiosity, cultural values, and public-health decisions has spurred healthcare professionals and other stakeholders, including religious leadership and policymakers, to examine these factors and formulate effective strategies while promoting cooperation among religious communities to ensure adoption of proper procedures or at least the necessary Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) to mitigate viral spread (36).

Certainly, religious leaders bear significant influence on the perceptions and behaviors of their followers and congregations, as evidenced by higher country-level religiosity leading to lower vaccination rates. In contrast, Roman Catholics showed the opposite trend, mostly due to the Pope's open advocacy for vaccines. This clearly shows the leveraging role religious leaders can assume in influencing the perceptions and behaviors of their followers in periods of public-health crisis. There is a need for a more-comprehensive approach to science communication, one that considers the needs and perspectives of religious communities in the context of public-health crises (1, 26). As we continue to navigate the challenges of COVID-19 and health crises certain to come, what is essential is considering the role of religious practices and beliefs in either spreading or mitigating the impact of infectious diseases (1, 22–27, 32). Future research should more deeply explore the religion's potential to promote wellbeing and resilience during public-health crises and derive the implications of this for public-health policy and practice (8, 11, 32).

Our discussion considered religion's positive as well as negative impacts during the COVID-19 epidemic. Understanding the complicated relationship between religious practice, belief, and public health is necessary for effective policymaking. It is important to include religious leaders and communities in encouraging compliance to health guidelines, and further, to better understand and promote the role of religion in maintaining wellbeing and resilience during health crises.

As we look ahead to the future, examining our current public health situation raises some pertinent questions. How can religious-based approaches help strengthen adherence to measures such as vaccinations and mask usage? To what degree will technology and virtual platforms impact how people practice religion going forward — is there potential for lasting effects on faith communities and individual believers alike? Also, it's crucial to consider how religion can play a role in shaping public health policies and regulations. This might involve studying how religious organizations and leaders contribute to creating, implementing, and evaluating these policies, and also discovering the most suitable methods to take religious perspectives into account when planning public health initiatives. These are some pressing research topics worth exploring in future to gain deeper insights into ways that religious institutions play critical roles during this pandemic period.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on people globally for the past 3 years, with vaccine hesitancy greatly hindering efforts to curb its effects. To combat this, collaborative efforts among religious leaders, governments, and scientists remain crucial to building trust and promoting vaccine uptake. It is essential to recognize that effective communication strategies and direct channels are necessary to reach and ease the fears of vaccine-hesitant populations, especially within those communities with strong or strict religious and psychospiritual beliefs. Tailored messaging that is culturally and religiously sensitive has been shown to be more effective in reaching these populations. Religious leaders and institutions can play critical roles in disseminating accurate and evidence-based vaccine information. For instance, faith-based advocacy can help reach certain vaccine-hesitant populations in religious communities. What is important to acknowledge and transcend, however, are the challenges and limitations of such efforts, for political or ideological barriers may exist between certain religious groups and governments that could hinder collaboration.

More generally, governments should concurrently take proactive measures to ensure health safety, equal access to healthcare, and non-discrimination across all communities. Collaborative efforts among all stakeholding groups—religious, scientific, healthcare, and governmental—are necessary to ensure successful vaccination campaigns to curb the spread of pandemics, COVID-19 or those of the future. To this end, it is crucial to survey and provide specific examples of successful collaborations between religious leaders, governments, and scientists to promote vaccine uptake. These should include case studies and real-world examples of faith-based advocacy efforts that have successfully reached vaccine-hesitant populations. Only through such collaborative efforts, can we ensure that all communities receive accurate information and access to vaccinations.

One limitation of this review paper is that it focuses mainly on challenges faced by religious communities during the COVID-19 pandemic without exploring other factors that may contribute to vaccine hesitancy or resistance. This paper also focuses primarily on examples from the Western, Arabs and African contexts, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or cultural contexts. Additionally, while this paper highlights the importance of engaging religious leaders in promoting vaccination acceptance, it does not explore potential challenges or barriers to such engagement. Our methodology follows a systematic approach, sharing similarities with established guidelines such as PRISMA or Cochrane, but does not strictly adhere to these guidelines. However, our review maintains rigor and transparency, which are key elements of a reliable review process.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

SAh, TB, and GA designed the study and developed the original protocol. SAh and LJ assisted with the initial screening of papers, data extraction, and the literature search. VS, LJ, and SAy contributed to writing the manuscript, including the methods section and synthesis of studies, and also participated in the interpretation of results. LJ, AB, SAy, and NM were involved in data analysis, interpretation of results, and writing several sections of the manuscript. MT, GG, and AB contributed to writing the discussion and conclusion sections. LJ and SAy contributed to writing the results, discussion section, and references. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

We express our gratitude to our co-workers, collaborators, language editors, and librarians for their invaluable support and assistance during the writing of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Lee M, Lim H, Xavier MS, Lee EY. “A divine infection”: a systematic review on the roles of religious communities during the early stage of COVID-19. J Relig Health. (2022) 61:866–919. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01364-w

2. Idler EL. Religion as a Social Determinant of Public Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2014).

3. Widiyanto A. Religion and covid-19 in the era of post-truth: the case of indonesia. Int. J. Islamic Thought. (2020) 18:1–12. doi: 10.24035/ijit.18.2020.176

4. Halbfinger DM. Virus Soars Among Ultra-Orthodox Jews as Many Flout Israel's Rules. The New York Times (2020).

5. Osei-Tutu A, Affram AA, Mensah-Sarbah C, Dzokoto VA, Adams G. The impact of COVID-19 and religious restrictions on the well-being of ghanaian christians: the perspectives of religious leaders. J Relig Health. (2021) 60:2232–49. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01285-8

6. Sulkowski L, Ignatowski G. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on organization of religious behaviour in different christian denominations in Poland. Religions. (2020) 11:254. doi: 10.3390/rel11050254

7. Ting RS-K, Aw Yong Y-Y, Tan M-M, Yap C-K. Cultural responses to COVID-19 pandemic: religions, illness perception, and perceived stress. Front. Psychol. (2021) 12:634863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.634863

8. Counted V, Pargament KI, Bechara AO, Joynt S, Cowden RG. Hope and well-being in vulnerable contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic: does religious coping matter? J Posit Psychol. (2022) 17:70–81. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1832247

9. Weinberger-Litman SL, Litman L, Rosen Z, Rosmarin DH, Rosenzweig C, A. Look at the first quarantined community in the usa: response of religious communal organizations and implications for public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Relig Health. (2020) 59:2269–82. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01064-x

10. Begović N. Restrictions on religions due to the covid-19 pandemic: responses of religious communities in bosnia and herzegovina. J. Law Relig State. (2020) 8:228–50. doi: 10.1163/22124810-2020007

11. Prazeres F, Passos L, Simões JA, Simões P, Martins C, Teixeira A. COVID-19-related fear and anxiety: spiritual-religious coping in healthcare workers in Portugal. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 18:220. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010220

12. Oxholm T, Rivera C, Schirrman K, Hoverd WJ. New Zealand religious community responses to COVID-19 while under level 4 lockdown. J Relig Health. (2021) 60:16–33. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01110-8

13. Fardin MA. COVID-19 epidemic and spirituality: a review of the benefits of religion in times of crisis. Jundishapur J Chronic Dis Care. (2020) 9:e104260. doi: 10.5812/jjcdc.104260

14. Lorea CE. Religious returns, ritual changes and divinations on COVID-19. Soc Anthropol. (2020) 28:307–8. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12865

15. Parish H. The absence of presence and the presence of absence: Social distancing, sacraments, and the virtual religious community during the COVID-19 pandemic. Religions. (2020) 11:276. doi: 10.3390/rel11060276

16. Delap D. How We Shared the Bread Wine on Zoom. (2020). Available online at: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2020/17-april/comment/opinion/how-we-shared-the-bread-and-wine-on-zoom (accessed April 14, 2020).

17. Seryczynska B, Oviedo L, Roszak P, Saarelainen S-MK, Inkilä H, Albaladejo JT, et al. Religious capital as a central factor in coping with the COVID-19: clues from an international survey. Eur. J. Sci. Theol. (2021) 17:67–81. Available online at: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/resource/en/covidwho-1187622

18. Ab Rahman Z, Kashim M, AY MN, Saari CZ, Hasan AZ, Ridzuan AR, et al. Critical review of religion in coping against the COVID-19 pandemic by former COVID-19 Muslim patients in Malaysia. International Journal of Critical Reviews. (2020).

19. Sisti LG, Buonsenso D, Moscato U, Costanzo G, Malorni W. The role of religions in the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:1691. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20031691

20. Dein S. COVID-19 and the apocalypse: religious and secular perspectives. J Relig Health. (2021) 60:5–15. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01100-w

21. Quadri SA, Padala PR. An aspect of Kumbh Mela massive gathering and COVID-19. Curr Trop Med Rep. (2021) 8:225–30. doi: 10.1007/s40475-021-00238-1

22. Quadri SA. COVID-19 and religious congregations: implications for spread of novel pathogens. Int J Inf Dis. (2020) 96:219–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.007

23. Al-Rousan N, Al-Najjar H. Is visiting Qom spread CoVID-19 epidemic in the Middle East. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2020) 24:5813–8. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202005_21376

24. Kim H-J, Hwang H-S, Choi Y-H, Song H-Y, Park J-S, Yun C-Y, et al. The delay in confirming COVID-19 cases linked to a religious group in Korea. J. Prev Med Public Health. (2020) 53:164. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.088

25. Linke M, Jankowski KS. Religiosity and the spread of COVID-19: a multinational comparison. J Relig Health. (2022) 61:1641–56. doi: 10.1007/s10943-022-01521-9

26. Taragin-Zeller L, Rozenblum Y, Baram-Tsabari A. Public engagement with science among religious minorities: lessons from COVID-19. Sci Commun. (2020) 42:643–78. doi: 10.1177/1075547020962107

27. Hill TGKB AM. The blood of Christ compels them: State religiosity and state population mobility during the coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. J Relig Health. (2020) 59:2229–42. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01058-9

28. Boguszewski R, Makowska M, Bozewicz M, Podkowińska M. The COVID-19 pandemic's impact on religiosity in Poland. Religions. (2020) 11:646. doi: 10.3390/rel11120646

29. Levin J, Bradshaw M. Determinants of COVID-19 skepticism and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy: findings from a national population survey of US adults. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13477-2

30. Perry SL, Whitehead AL, Grubbs JB. Culture wars and COVID-19 conduct: christian nationalism, religiosity, and Americans' behavior during the coronavirus pandemic. J Sci Study Relig. (2020) 59:405–16. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12677

31. Perry SL, Whitehead AL, Grubbs JB. Prejudice and pandemic in the promised land: how white christian nationalism shapes Americans' racist and xenophobic views of COVID-19. Ethn Racial Stud. (2021) 44:759–72. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2020.1839114

32. Pirutinsky S, Cherniak AD, Rosmarin DH. COVID-19, mental health, and religious coping among American Orthodox Jews. J Relig Health. (2020) 59:2288–301. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01070-z

33. Frei-Landau R. “When the going gets tough, the tough get—Creative”: Israeli Jewish religious leaders find religiously innovative ways to preserve community members' sense of belonging and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma Theor Res Prac Policy. (2020) 12:S258. doi: 10.1037/tra0000822

34. Impouma B, Williams GS, Moussana F, Mboussou F, Farham B, Wolfe CM, et al. The first 8 months of COVID-19 pandemic in three West African countries: leveraging lessons learned from responses to the 2014–2016 Ebola virus disease outbreak. Epidemiol Inf. (2021) 149:e258. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821002053

35. Williams JT, Fisher MP, Bayliss EA, Morris MA, O'Leary ST. Clergy attitudes toward vaccines and vaccine advocacy: a qualitative study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2020) 16:2800–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1736451

36. Orlandi LB, Febo V, Perdichizzi S. The role of religiosity in product and technology acceptance: Evidence from COVID-19 vaccines. Technol Forecast Soc Change. (2022) 185:122032. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122032

37. Yezli S, Khan A. COVID-19 pandemic: it is time to temporarily close places of worship and to suspend religious gatherings. J Travel Med. (2021) 28:taaa065. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa065

38. Yezli S, Khan A. COVID-19 social distancing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: bold measures in the face of political, economic, social and religious challenges. Travel Med Infect Dis. (2020) 37:101692. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101692

39. Gautret P, Al-Tawfiq JA, COVID. 19: Will the 2020 Hajj pilgrimage and Tokyo Olympic Games be cancelled? Travel Med Infect Dis. (2020) 34:101622. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101622

40. Waitzberg R, Davidovitch N, Leibner G, Penn N, Brammli-Greenberg S. Israel's response to the COVID-19 pandemic: tailoring measures for vulnerable cultural minority populations. Int J Equity Health. (2020) 19:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01191-7

41. Thompkins Jr F, Goldblum P, Lai T, Hansell T, Barclay A, Brown LM, et al. culturally specific mental health and spirituality approach for African Americans facing the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma Theor Res Prac Policy. (2020) 12:455. doi: 10.1037/tra0000841

42. Galang JRF. Science and religion for COVID-19 vaccine promotion. J Public Health. (2021) 43:e513–e4. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab128

43. Greene T, Bloomfield MA, Billings J. Psychological trauma and moral injury in religious leaders during COVID-19. Psychol Trauma Theor Res Prac Policy. (2020) 12:S143. doi: 10.1037/tra0000641

44. Rosenberg DE,. The Government Can't Save Ultra-Orthodox Jews From COVID-19. Religious Leaders Can. (2020). Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/12/the-government-cant-save-ultra-orthodox-jews-from-covid-19-religious-leaders-can/ (accessed October 12, 2020).

45. Pandey G. India Covid: Kumbh Mela Pilgrims Turn Into Super-Spreaders. (2020). Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-57005563 (accessed April 29, 2023).

46. Ellis-Petersen H, Hassan A. Kumbh Mela: How a Superspreader Festival Seeded COVID Across India. (2020). Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/30/kumbh-mela-how-a-superspreader-festival-seeded-covid-across-india (accessed April 29, 2023).

47. Staff R. Decrying Vaccines, Tanzania Leader Says 'God will Protect' From COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-tanzania/decrying-vaccines-tanzania-leader-says-god-will-protect-from-covid-19-idUSKBN29W1Z6 (accessed April 29, 2023).

48. Frayer L, Estrin D, Arraf J. Coronavirus Is Changing The Rituals Of Death For Many Religions. (2020). Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/04/07/828317535/coronavirus-is-changing-the-rituals-of-death-for-many-religions (accessed April 29, 2023).

49. Pierson D,. Funeral Pyres Burn. Gravediggers Know No Rest. India's COVID-19 Crisis is a ‘Nightmare'. (2021) Available online at: https://www.latimes.com/2021, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-04-28/india-covid-second-wave (accessed April 28, 2021).

50. Stack L. 'Plague on a Biblical Scale': New York's Hasidic Communities Hit Hard by Coronavirus. (2021). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/21/nyregion/coronavirus-jews-hasidic-ny.html (accessed April 28, 2021).

51. Klobucista C, Maizland L. How the World Has Learned to Grieve in a Pandemic. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/2020, https://www.cfr.org/article/coronavirus-funeral-how-world-has-learned-grieve-pandemic (accessed April 28, 2021).

52. Burrell A, Selman LE. How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives' mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed methods review with implications for COVID-19. OMEGA-J. Death Dying. (2022) 85:345–83. doi: 10.1177/0030222820941296

53. McElwee J. Pope Francis Suggests People Have Moral Obligation to Take Coronavirus Vaccine. New York, NY: National Catholic Reporter (2021).

54. Hegarty S. 1The Gospel Truth?' Covid-19 Vaccines and the Danger of Religious Misinformation. New York, NY: BBC (2021).

Keywords: COVID-19, religion, spirituality, public health, pandemic, misinformation, vaccine hesitancy and refusal, conspiracy

Citation: Ayub S, Anugwom GO, Basiru T, Sachdeva V, Muhammad N, Bachu A, Trudeau M, Gulati G, Sullivan A, Ahmed S and Jain L (2023) Bridging science and spirituality: the intersection of religion and public health in the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 14:1183234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1183234

Received: 09 March 2023; Accepted: 02 May 2023;

Published: 19 May 2023.

Edited by:

Renato de Filippis, Magna Græcia University, ItalyReviewed by:

Choirul Mahfud, Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology, IndonesiaCopyright © 2023 Ayub, Anugwom, Basiru, Sachdeva, Muhammad, Bachu, Trudeau, Gulati, Sullivan, Ahmed and Jain. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lakshit Jain, TGFrc2hpdC5qYWluQGN0Lmdvdg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.