95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 26 May 2023

Sec. Mood Disorders

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1139705

This article is part of the Research Topic Risk Behavior and its Connection to Addiction View all 7 articles

Background: Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) severely challenges mental health in adolescents. Childhood maltreatment experience acts as high-risk factor for adolescents to engage in NSSI behaviors. On the other hand, impulsivity or loss of control sets the threshold for NSSI execution. Here we examined the effects of childhood maltreatment on adolescent NSSI-related clinical outcomes and the potential role of impulsivity.

Methods: We assessed the clinical data of 160 hospitalized NSSI adolescents and recruited 64 age-matched healthy subjects as a control group. The clinical symptoms of NSSI are expressed by the NSSI frequency, depression, and anxiety measured by the Ottawa Self-Injury Inventory, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Childhood maltreatment and impulsivity were assessed with Childhood Trauma Questionnaire and Barratt Impulsiveness Scale.

Results: The results showed that when compared to HC group, NSSI group is more likely to experience childhood maltreatment. Notably, NSSI group with Childhood maltreatment accompanies higher trait impulsivity and exacerbated clinical outcomes, such as NSSI frequency, depression and anxiety symptoms. Mediation analyses indicated that the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI-related clinical outcomes was partially explained by impulsivity.

Conclusion: We found that NSSI adolescents have a higher proportion of childhood maltreatment. Impulsivity plays a mediating role between childhood maltreatment and NSSI behaviors.

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the direct and intentional destruction of body tissue without any intent to die (1). Adolescents are at high risk of developing NSSI behaviors. The prevalence of NSSI in children and adolescents is about 19.5% worldwide and about 27.4% in the Chinese population aged 13 to 18 years (2, 3). NSSI commonly aims to reduce negative emotions, such as stress, anxiety, and self-blame (4–7). Individuals frequently report experiencing an immediate sense of relief during self-injury (8). In addition to being a severe threat to adolescents’ mental and physical health, NSSI can also cause severe social impacts and economic burdens (9, 10). Understanding the risk factors and early prevention is critical in reducing the harm caused by NSSI.

Childhood maltreatment could increase the risk of experiencing mental disorders in adolescence and adulthood (11–13). Childhood maltreatment typically includes five subtypes: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Previous studies indicate that childhood maltreatment is a risk factor for developing NSSI behaviors, and any type of childhood maltreatment increases an individual’s risk of engaging in NSSI behaviors (14, 15). In addition, some studies have found that individuals with Childhood maltreatment report more severe depression and anxiety symptoms (16, 17). Childhood maltreatment is associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety, including in NSSI adolescents (18). A retrospective study of a large sample reported that participants who were abused during childhood were more likely to have more psychiatric problems at age 18, including depression, anxiety, self-injury, and alcohol dependence (19). The abuse experience was also associated with poorer treatment outcomes, with a one-year follow-up of outpatients found that depressed patients with a history of maltreatment were more difficult to remit (20). Given childhood maltreatment’s devastating and long-term negative effects, the mechanisms underlying the complex relationship between traumatic childhood experiences and NSSI behaviors have also attracted increasing attention.

One possible factor of childhood maltreatment influencing NSSI behavior is impulsivity (21). Impulsivity is a complex concept involving the pathophysiology of multiple psychiatric disorders (22). In both the community and hospital samples, NSSI adolescents reported stronger impulsivity (23, 24). Impulsivity was associated with more severe depression and anxiety symptoms (25). It is well known that both childhood maltreatment and high impulsivity are important risk factors for NSSI, but few studies have explored whether they interact with NSSI. Individual studies have focused on one type of childhood maltreatment. A meta-analysis found that childhood maltreatment was positively correlated with trait impulsivity, particularly in emotional abuse (21). Another study of adults experiencing sexual abuse also found that, impulsivity explained 11% of the association between suicidal self-injury and sexual abuse, and 4% of the association between NSSI and sexual abuse (26). More suicide-related studies revealed that childhood maltreatment could directly predict suicidal behavior, and impulsivity partially mediates the pathway (27–29). These evidences suggest that childhood maltreatment and impulsivity are indeed correlated in suicidal populations and work together on suicidal behavior. Since NSSI partially overlaps with the neurobiological characteristics of suicidal behavior, and we speculate that impulsivity may also mediate the effects of childhood maltreatment on NSSI-related clinical outcomes. At present, few studies have comprehensively explored the role of impulsivity in the association between childhood maltreatment and multiple clinical outcomes in NSSI adolescents, but the implementation of such research is conducive to the prevention of NSSI.

Here, considering that childhood maltreatment and high impulsivity are associated with more severe clinical outcomes in adolescents with NSSI, we aimed to (1) characterize the performance of childhood maltreatment and impulsivity in NSSI adolescents, (2) examine the effects of having childhood maltreatment on impulsivity and NSSI behavior. Based on previous findings of the relationship between childhood maltreatment, impulsivity, and more severe clinical symptoms (more frequent NSSI, anxiety, depression), We further validated a theoretical mediation model of whether impulsivity mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and NSSI-related clinical symptoms (Figure 1).

A total of 160 NSSI adolescent inpatients of Ningbo Kangning Hospital and 64 healthy controls (HC) were recruited from April 2021 to July 2022. Inclusion criteria for NSSI adolescents were as follows: (1) age between 12 and 18 years; (2) DSM-5 diagnosis of major depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and bipolar I disorder (major depressive episode); and (3) five or more days engaged in NSSI during the past year. Exclusion criteria were (1) history of modified electroconvulsive therapy (MECT) treatment within the past 6 months; (2) suicide attempts during the last year; (3) suicidal plans or acute risk for suicide; (4) unable to understand or comply with the study procedure. All HC adolescents had no history of psychiatric disorders and self-injury. Two professional psychiatrists completed the entire interview process for the entry screening. All adolescent participants and their legal guardians signed written informed consent, and the study was approved by the ethics committee from Ningbo Kangning Hospital.

Demographic and clinical information, including sex, age, grade, only one-child family, urbanization and family history of mental disorders, were collected from all participants. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to access current self-reported levels of anxiety. Twenty-one items were scored using a 4-point Likert scale (0–3). Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety. To access the severity of depressive symptoms, we used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a four-point (0–3), 21-item self-assessment scale. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of BAI and BDI are 0.938 and 0.947, respectively. For NSSI adolescents, NSSI-related information was accessed using the Ottawa Self-Injury Inventory (OSI) (30). NSSI frequency in the past month was measured by the question “How often in the past month have you actually injured yourself, without the intention to kill yourself?” options are “not at all,” “at least once,” “weekly,” and “daily,” with a score of 0–3.

Childhood maltreatment experiences were assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (31). This 28-item self-report scale is scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true), consisting of 5 subscales: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Physical abuse ≥10, sexual abuse ≥8, emotional abuse ≥13, physical neglect ≥10, and emotional neglect ≥15 was considered trauma exposure (32). Cronbach’s alpha for CTQ in our sample was 0.812.

Trait impulsivity was assessed by the 30-item Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11), which includes three dimensions: nonplanning impulsivity, motor impulsivity, and attentional impulsivity. Each subscale contains 10 items with a five-point Likert scale (1 “never” to 5 “very often”), with a higher score indicating stronger trait impulsivity. The Chinese version of BIS-11 used in this study has good reliability and validity (33). The Cronbach’s alpha for BIS was 0.916 in the present study.

Comparisons of the clinical and demographic variables between HC and NSSI groups were performed by independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to test for differences in impulsivity and clinical outcomes between those with and without childhood maltreatment within the NSSI group. Spearman correlation was used to explore the relationship between different types of childhood maltreatment, impulsivity, and clinical outcomes in NSSI group. To verify the mediation pathway from childhood maltreatment, through the role of impulsivity, to clinical outcomes of NSSI, we further performed three independent mediation effect testing. Harman’s single-factor test (34) was used to test for possible common method bias. The mediation effects were carried out using the PROCESS macro (35) for SPSS (version 26, IBM), and 5,000 bootstrap samples were constructed for the significance of mediation effects. If the 95% confidence interval of the path coefficient does not contain 0, the effect would be significant.

The basic characteristics of all participants are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between HC and NSSI groups for age, education years, sex, only one-child family, urbanization and family history of mental disorders (all p > 0.05). The mean (SD) score of the NSSI frequency (past month) was 1.76 (0.95), and the onset age of NSSI was 12.62 (1.663). NSSI adolescents have more severe depressive (t = −17.071, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −2.112) and anxiety symptoms (t = −15.701, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −1.914) symptoms than HC adolescents. The level of BIS total (t = −7.205, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −1.064) was significantly higher in NSSI adolescents compared to HC. Moreover, NSSI adolescents also experienced more childhood maltreatment, with higher scores in emotional abuse (t = −9.972, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −1.300), physical abuse (t = −7.342, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.883), sexual abuse (t = −5.000, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.565), emotional neglect (t = −9.250, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −1.307), physical neglect (t = −5.510, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.829), and CTQ total (t = −11.605, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −1.539) than HC adolescents (Table 1).

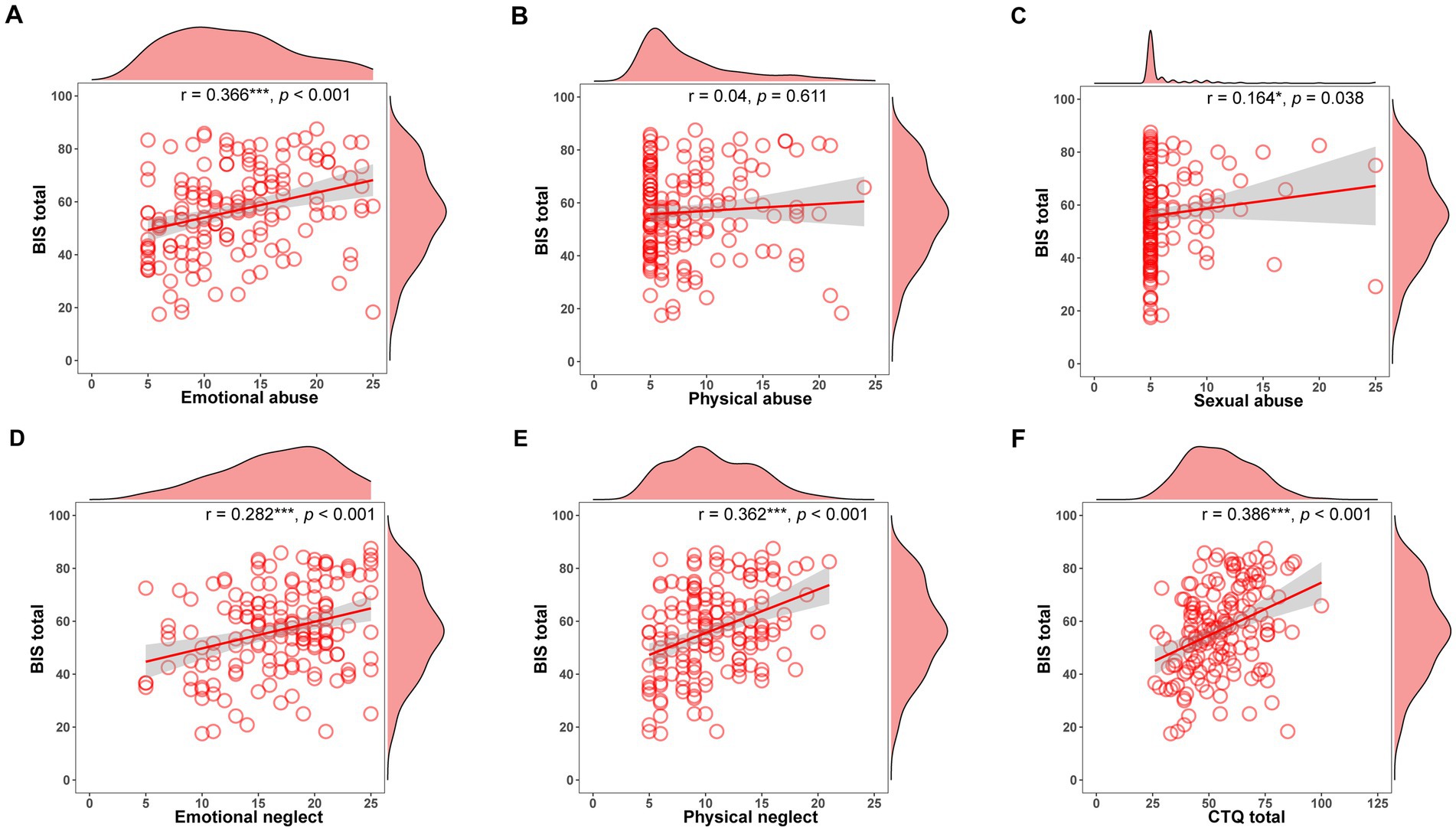

In our NSSI hospitalized adolescents, 47.5% experienced emotional abuse, 28.75% experienced physical abuse, 17.5% experienced sexual abuse, and 70.63 and 56.88% reported emotional neglect and physical neglect (Figure 2). NSSI adolescents who have experienced emotional abuse have more frequency of self-injury (Supplementary Table S1). NSSI adolescents with emotional abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect have more symptoms of depression and anxiety (Supplementary Tables S1–S5). Figure 3 presents the relationship between childhood maltreatment subtypes and impulsivity. Emotional abuse (r = 0.366, p < 0.001), emotional neglect (r = 0.282, p < 0.001), physical neglect (r = 0.362, p < 0.001) and CTQ total score (r = 0.386, p < 0.001) were positively correlated with BIS total score. The sexual abuse score was marginally correlated with BIS total score (r = 0.164, p = 0.038).

Figure 3. The relationship between childhood maltreatment subtypes and impulsivity in NSSI group. (A) Correlation between BIS total and emotional abuse. (B) Correlation between BIS total and physical abuse. (C) Correlation between BIS total and sexual abuse. (D) Correlation between BIS total and emotional neglect. (E) Correlation between BIS total and physical neglect. (F) Correlation between BIS total and CTQ total. BIS, barratt impulsivity scale; CTQ, childhood trauma questionnaire. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The association between childhood maltreatment, impulsivity, and clinical outcome was evaluated (Supplementary Table S6). Emotional abuse (r = 0.245, p = 0.002) and BIS total score (r = 0.319, p < 0.001) were positively correlated with NSSI frequency scores (past month). CTQ total and BIS total were significantly associated with BDI and BAI. Consequently, further mediation models were constructed separately for childhood maltreatment, impulsivity, and NSSI clinical outcomes.

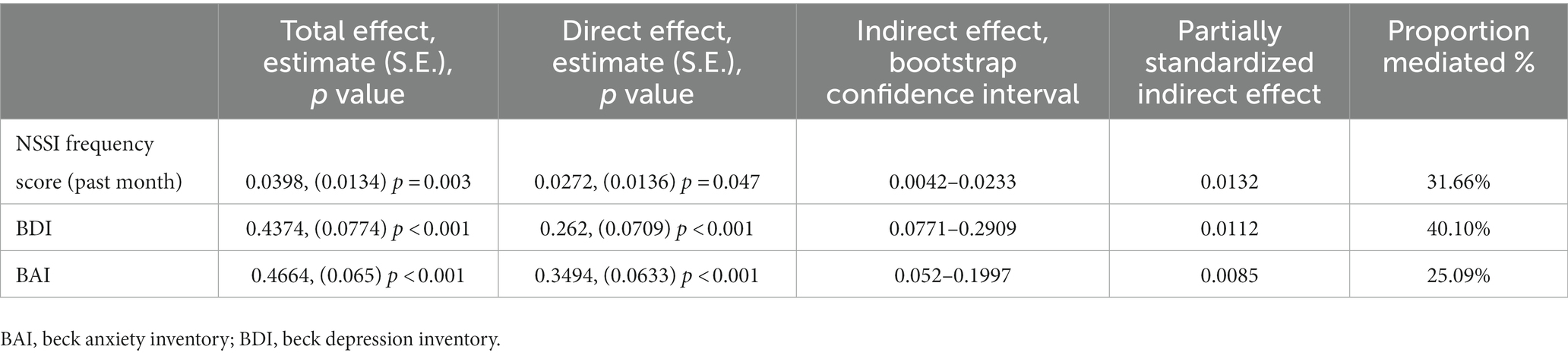

After controlling for sex and age, the mediating effects of impulsivity between emotional abuse and NSSI frequency scores (past month) were tested. Impulsivity mediated 31.66% of the emotional abuse on NSSI frequency scores (past month). In addition, two separate mediation analyses examined the indirect effect of childhood maltreatment total on BDI and BAI, respectively, which was mediated by impulsivity. Impulsivity mediated 40.10% of the effect of childhood maltreatment total on BDI and 25.09% of the effect on BAI. Table 2 shows the results of the mediation analysis.

Table 2. Impulsivity as a mediator in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and clinical outcome (total effect, direct effect, and indirect effect).

In the present study, by investigating hospitalized NSSI adolescents, we demonstrated that the NSSI adolescents scored higher on childhood abuse than HC adolescents. NSSI adolescents with childhood traumatic experiences have stronger impulsivity, and more severe clinical outcomes than those without, and impulsivity is a significant mediator of the effect of childhood maltreatment on the frequency of self-injury, depression and anxiety symptoms in NSSI adolescents.

Overall, all types of maltreatment experience increased adolescent engagement in NSSI, which is consistent with most studies. However, the processes that act on NSSI may be distinct for different types of abuse histories. Emotional abuse is directly associated with NSSI, whereas the effects of sexual and physical abuse may be indirect (36). From the perspective of stress regulation, this may be associated with activation patterns of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis). Emotional abuse may impair the resilience of HPA axis to acute stress response, and repeated exposure to physical abuse may affect the sensitivity of HPA axis (37). The present findings also suggested that adolescents with NSSI showed higher levels of impulsivity, and impulsivity was positively correlated with NSSI frequency and severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms (38–40). A longitudinal study identified impulsivity as a potential risk factor for NSSI, independently predicting the new onset of NSSI (41). This suggests that those who act quickly and without thoughtful consideration are more likely to self-injury than those who think deeply (42).

The prevalence of emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect (47.5, 28.75, 17.5, 70.63, and 56.88%, respectively) among the NSSI adolescents in this study were higher than previously reported global and Chinese adolescent prevalence rates (43, 44). This may be due to the different sample sizes and the higher disease severity in hospitalized patients. However, the prevalence of our sample was consistent with another study of Chinese college students (45), with the highest prevalence of physical neglect and emotional neglect and the lowest prevalence of sexual abuse. Moreover, NSSI adolescents who experience childhood maltreatment report more symptoms of depression and anxiety. Most previous studies have focused on sexual abuse, but a growing body of evidence finds that emotional abuse/neglect exerts an even greater effect on mental health (15). Emotional abuse is often a long-term chronic state that may cause individuals to become trapped in adverse and dysregulated emotions, leading to dysfunctional behaviors of coping (46), such as self-injury and suicide. The present study also found that NSSI adolescents exposed to emotional abuse had more frequency of self-injury.

In addition, NSSI adolescents with a history of childhood maltreatment have higher impulsivity, which is in line with the results of past studies (47, 48). In a longitudinal study of adolescents, a history of physical abuse and physical neglect was found to significantly predict subsequent impulsivity levels (49). Another study found that emotional abuse/neglect was strongly associated with impulsivity (50). And a study of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging in adults may explain the neurophysiological mechanism of childhood maltreatment affecting impulsivity (51). The study found that adults with childhood maltreatment experience self-reported higher impulsivity, and reduced functional connectivity (FC) between the inferior parietal lobule and the middle frontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. Further mediation analysis found that the effect of childhood maltreatment on impulsivity was mediated by FC between the inferior parietal lobule and the prefrontal cortex. Consequently, childhood maltreatment induces alterations in brain regions associated with response inhibition, which would enhance impulsivity and further increase vulnerability to adverse outcomes (21, 52). This contributes to the understanding of the core findings of this study, where impulsivity partially mediated the effects of childhood maltreatment on depression, anxiety symptoms, and NSSI frequency in adolescents with NSSI. When facing stressful events and experiencing negative emotions, impulsivity may drive individuals toward self-injurious behavior without adequate consideration of the potential negative consequences (53). As time goes on, the frequency and severity of NSSI increases (54). Adolescence is a critical stage of lifespan characterized by substantial neurodevelopment and a spontaneous increase in impulsivity (55). The onset of NSSI was 12–14 years (56), which tends to increase in early adolescence (57), while declining substantially in late adolescence and slowly in early adulthood (58). This characteristic overlaps with the developmental features of brain impulsivity. Traumatic experiences may have long-term neurobiological effects on the human brain resulting in psychopathology (59). Early-life adversity triggers changes in brain structure and function, including emotional and control brain regions. Abnormalities in emotion-related brain areas may lead to emotional dysregulation. Subsequently, dysfunction in control-related brain areas results in impaired inhibitory control and exhibits abnormally high impulsivity (60). Individuals might hardly suppress their negative emotions and self-injurious impulses, then engage in self-injurious behaviors uncontrollably, which may be one of the neurophysiological mechanisms of self-injurious behaviors.

There were several limitations in the current study. At first, the cross-sectional design of this study cannot reveal the causality of childhood maltreatment experiences, trait impulsivity, and relevant characteristics of NSSI behavior. Longitudinal studies were required to help validate the mediating model in NSSI adolescents. Second, We did not include adolescents with psychiatric disorders without NSSI as another control group, and a comparison of adolescents with psychiatric disorders with and without NSSI will improve the convincing of the conclusions. Third, the severity of NSSI was not assessed, which is a complex concept that may require weighting for frequency of NSSI, degree of physical injury of body regions, etc. Future study is needed to improve the comprehensiveness of the NSSI measurement. Besides, the mechanisms and risk factors for NSSI require further investigation, which helps the development of more effective prevention and intervention for NSSI.

This work highlights the importance of childhood maltreatment and trait impulsivity for NSSI. Our findings further clarify the direct effects and mediating role of childhood maltreatment and impulsivity on NSSI-related clinical outcomes, respectively, broadening the research on NSSI. The results also have implications in NSSI clinical practices that trait impulsivity and childhood maltreatment could be potential targets in NSSI intervention and prevention.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee from Ningbo Kangning Hospital. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

XL, X-LL, and Y-JW had full access to all study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. XL, X-LL, Y-JW, D-SZ, and T-FY were responsible for the study of concept and design, and critically revised the manuscripts. All authors were involved in the acquisition and interpretation of the data, and read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was funded by the Medical and Health Brand Discipline in Ningbo (PPXK2018-08).

We thank the lab members for their help during the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1139705/full#supplementary-material

1. Nock, MK . Actions speak louder than words: an elaborated theoretical model of the social functions of self-injury and other harmful behaviors. Appl Prev Psychol. (2008) 12:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.appsy.2008.05.002

2. Yang, X , and Feldman, MW . A reversed gender pattern? A meta-analysis of gender differences in the prevalence of non-suicidal self-injurious behaviour among Chinese adolescents. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:66. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4614-z

3. Lim, K-S , Wong, CH , Mcintyre, RS , Wang, J , Zhang, Z , Tran, BX, et al. Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4581. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224581

4. Nock, MK , Prinstein, MJ , and Sterba, SK . Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: a real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. J Abnorm Psychol. (2009) 118:816–27. doi: 10.1037/a0016948

5. Hasking, P , Whitlock, J , Voon, D , and Rose, A . A cognitive-emotional model of NSSI: using emotion regulation and cognitive processes to explain why people self-injure. Cogn Emot. (2017) 31:1543–56. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1241219

6. Miller, AB , Eisenlohr-Moul, T , Glenn, CR , Turner, BJ , Chapman, AL , Nock, MK, et al. Does higher-than-usual stress predict nonsuicidal self-injury? Evidence from two prospective studies in adolescent and emerging adult females. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2019) 60:1076–84. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13072

7. Hauber, K , Boon, A , and Vermeiren, R . Non-suicidal self-injury in clinical practice. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:502. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00502

8. Kirtley, OJ , O'Carroll, RE , and O'Connor, RC . The role of endogenous opioids in non-suicidal self-injurious behavior: methodological challenges. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2015) 48:186–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.007

9. Mannekote Thippaiah, S , Shankarapura Nanjappa, M , Gude, JG , Voyiaziakis, E , Patwa, S , Birur, B, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury in developing countries: a review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 67:472–82. doi: 10.1177/0020764020943627

10. Yang, J , Chen, Y , Yao, G , Wang, Z , Fu, X , Tian, Y, et al. Key factors selection on adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury: a support vector machine based approach. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1049069. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1049069

11. Angelakis, I , Austin, JL , and Gooding, P . Association of childhood maltreatment with suicide behaviors among young people a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2012563. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12563

12. McKay, MT , Cannon, M , Chambers, D , Conroy, RM , Coughlan, H , Dodd, P, et al. Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2021) 143:189–205. doi: 10.1111/acps.13268

13. Edalati, H , and Krank, MD . Childhood maltreatment and development of substance use disorders: a review and a model of cognitive pathways. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2016) 17:454–67. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584370

14. Duke, NN , Pettingell, SL , McMorris, BJ , and Borowsky, IW . Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. (2010) 125:e778–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597

15. Liu, RT , Scopelliti, KM , Pittman, SK , and Zamora, AS . Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:51–64. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30469-8

16. King, AR . Childhood adversity links to self-reported mood, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. J Affect Disord. (2021) 292:623–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.112

17. Struck, N , Krug, A , Yuksel, D , Stein, F , Schmitt, S , Meller, T, et al. Childhood maltreatment and adult mental disorders - the prevalence of different types of maltreatment and associations with age of onset and severity of symptoms. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113398. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113398

18. Vallati, M , Cunningham, S , Mazurka, R , Stewart, JG , Larocque, C , Milev, RV, et al. Childhood maltreatment and the clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder in adolescence and adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol. (2020) 129:469–79. doi: 10.1037/abn0000521

19. Newbury, JB , Arseneault, L , Moffitt, TE , Caspi, A , Danese, A , Baldwin, JR, et al. Measuring childhood maltreatment to predict early-adult psychopathology: comparison of prospective informant-reports and retrospective self-reports. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) 96:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.020

20. Yrondi, A , Aouizerate, B , Bennabi, D , Richieri, R , D'Amato, T , Bellivier, F, et al. Childhood maltreatment and clinical severity of treatment-resistant depression in a French cohort of outpatients (FACE-DR): one-year follow-up. Depress Anxiety. (2020) 37:365–74. doi: 10.1002/da.22997

21. Liu, RT . Childhood maltreatment and impulsivity: a meta-analysis and recommendations for future study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2019) 47:221–43. doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0445-3

22. Robbins, TW , Gillan, CM , Smith, DG , de Wit, S , and Ersche, KD . Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends Cogn Sci. (2012) 16:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.009

23. Dougherty, DM , Mathias, CW , Marsh-Richard, DM , Prevette, KN , Dawes, MA , Hatzis, ES, et al. Impulsivity and clinical symptoms among adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury with or without attempted suicide. Psychiatry Res. (2009) 169:22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.011

24. Huang, Y-H , Liu, H-C , Tsai, F-J , Sun, F-J , Huang, K-Y , Chiu, Y-C, et al. Correlation of impulsivity with self-harm and suicidal attempt: a community study of adolescents in Taiwan. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017949. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017949

25. Gecaite-Stonciene, J , Saudargiene, A , Pranckeviciene, A , Liaugaudaite, V , Griskova-Bulanova, I , Simkute, D, et al. Impulsivity mediates associations between problematic internet use, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in students: a cross-sectional COVID-19 study. Front Psych. (2021) 12:634464. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.634464

26. de Cates, AN , Catone, G , Bebbington, P , and Broome, MR . Attempting to disentangle the relationship between impulsivity and longitudinal self-harm: epidemiological analysis of UK household survey data. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2019) 65:114–22. doi: 10.1177/0020764019827986

27. Dramilaraki, S , Antoniou, A , Porichi, E , Efstathiou, V , Michopoulos, I , Gournellis, R, et al. Childhood trauma and suicidality in bipolar disorder: the mediatory role of impulsivity. Psychiatrike. (2021) 32:103–12. doi: 10.22365/jpsych.2021.016

28. Ferraz, L , Portella, MJ , Vállez, M , Gutiérrez, F , Martín-Blanco, A , Martín-Santos, R, et al. Hostility and childhood sexual abuse as predictors of suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. (2013) 210:980–5. eng. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.004

29. Liu, RT , Walsh, RFL , Sheehan, AE , Cheek, SM , and Sanzari, CM . Prevalence and correlates of suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury in children: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. (2022) 79:718–26. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1256

30. Nixon, MK , Levesque, C , Preyde, M , Vanderkooy, J , and Cloutier, PF . The Ottawa self-injury inventory: evaluation of an assessment measure of nonsuicidal self-injury in an inpatient sample of adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2015) 9:26. doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0056-5

31. Bernstein, DP , Stein, JA , Newcomb, MD , Walker, E , Pogge, D , Ahluvalia, T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2003) 27:169–90. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

32. Bernstein, D , and Fink, L . Manual for the childhood trauma questionnaire. New York: The Psychological Corporation (1998).

33. Xian-Yun, LI , Phillips, MR , Dong, XU , Zhang, YL , Yang, SJ , Tong, YS, et al. Reliability and validity of an adapted Chinese version of Barratt impulsiveness scale. Chin Ment Health J. (2011) 25:610–5. doi: 10.1007/s12583-011-0163-z

34. Podsakoff, PM , MacKenzie, SB , Lee, J-Y , and Podsakoff, NP . Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. (2003) 88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

35. Hayes, A . Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J Educ Meas. (2013) 51:335–7. doi: 10.1111/jedm.12050

36. Thomassin, K , Shaffer, A , Madden, A , and Londino, DL . Specificity of childhood maltreatment and emotion deficit in nonsuicidal self-injury in an inpatient sample of youth. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 244:103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.050

37. Kuhlman, KR , Geiss, EG , Vargas, I , and Lopez-Duran, NL . Differential associations between childhood trauma subtypes and adolescent HPA-axis functioning. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2015) 54:103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.01.020

38. Janis, IB , and Nock, MK . Are self-injurers impulsive?: results from two behavioral laboratory studies. Psychiatry Res. (2009) 169:261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.041

39. Maxfield, BL , and Pepper, CM . Impulsivity and response latency in non-suicidal self-injury: the role of negative urgency in emotion regulation. Psychiatry Q. (2018) 89:417–26. doi: 10.1007/s11126-017-9544-5

40. Mo, J , Wang, C , Niu, X , Jia, X , Liu, T , and Lin, L . The relationship between impulsivity and self-injury in Chinese undergraduates: the chain mediating role of stressful life events and negative affect. J Affect Disord. (2019) 256:259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.074

41. Cassels, M , Neufeld, S , van Harmelen, A-L , Goodyer, I , and Wilkinson, P . Prospective pathways from impulsivity to non-suicidal self-injury among youth. Arch Suicide Res. (2020) 26:534–47. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2020.1811180

42. Hamza, CA , Willoughby, T , and Heffer, T . Impulsivity and nonsuicidal self-injury: a review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2015) 38:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.010

43. Wan, Y , Chen, J , Sun, Y , and Tao, F . Impact of childhood abuse on the risk of non-suicidal self-injury in mainland Chinese adolescents. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0131239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131239

44. Stoltenborgh, M , Bakermans-Kranenburg, MJ , Alink, LRA , and van Ijzendoorn, MH . The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Rev. (2015) 24:37–50. doi: 10.1002/car.2353

45. Fu, H , Feng, T , Qin, J , Wang, T , Wu, X , Cai, Y, et al. Reported prevalence of childhood maltreatment among Chinese college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0205808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205808

46. Crowell, SE , Beauchaine, TP , and Linehan, MM . A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: elaborating and extending Linehan's theory. Psychol Bull. (2009) 135:495–510. doi: 10.1037/a0015616

47. Freitag, S , Kapoor, S , and Lamis, DA . Childhood maltreatment, impulsive aggression, and suicidality among patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Psychol Trauma. (2022) 14:1256–62. doi: 10.1037/tra0001218

48. Cao, H , Meng, H , Geng, X , Lin, X , Zhang, Y , Yan, L, et al. Childhood emotional maltreatment and subsequent affective symptoms among chinese male drug users: the roles of impulsivity and psychological resilience. Psychol Trauma. (2022). doi: 10.1037/tra0001283

49. Oshri, A , Kogan, SM , Kwon, JA , Wickrama, KAS , Vanderbroek, L , Palmer, AA, et al. Impulsivity as a mechanism linking child abuse and neglect with substance use in adolescence and adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. (2018) 30:417–35. doi: 10.1017/S0954579417000943

50. Brown, S , Mitchell, TB , Fite, PJ , and Bortolato, M . Impulsivity as a moderator of the associations between child maltreatment types and body mass index. Child Abuse Negl. (2017) 67:137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.029

51. Pang, Y , Zhao, S , Li, Z , Li, N , Yu, J , Zhang, R, et al. Enduring effect of abuse: childhood maltreatment links to altered theory of mind network among adults. Hum Brain Mapp. (2022) 43:2276–88. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25787

52. Shin, SH , McDonald, SE , and Conley, D . Profiles of adverse childhood experiences and impulsivity. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 85:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.028

53. Chen, H , and Zhou, J . Research progress on the addictive characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury. Chin J Psychiatry. (2022) 55:64–8. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn113661-20210921-00130

54. Chapman, AL , Gratz, KL , and Brown, MZ . Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behav Res Ther. (2006) 44:371–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005

55. Whelan, R , Conrod, PJ , Poline, J-B , Lourdusamy, A , Banaschewski, T , Barker, GJ, et al. Adolescent impulsivity phenotypes characterized by distinct brain networks. Nat Neurosci. (2012) 15:920–5. doi: 10.1038/nn.3092

56. Nock, MK . Self-injury. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2010) 6:339–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258

57. Morgan, C , Webb, RT , Carr, MJ , Kontopantelis, E , Green, J , Chew-Graham, CA, et al. Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ. (2017) 359:j4351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4351

58. Moran, P , Coffey, C , Romaniuk, H , Olsson, C , Borschmann, R , Carlin, JB, et al. The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. (2012) 379:236–43. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61141-0

59. Brodsky, BS , Oquendo, M , Ellis, SP , Haas, GL , Malone, KM , and Mann, JJ . The relationship of childhood abuse to impulsivity and suicidal behavior in adults with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. (2001) 158:1871–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1871

Keywords: childhood maltreatment, emotional abuse, impulsivity, non-suicidal self-injury, adolescent

Citation: Li X, Liu X-L, Wang Y-J, Zhou D-S and Yuan T-F (2023) The effects of childhood maltreatment on adolescent non-suicidal self-injury behavior: mediating role of impulsivity. Front. Psychiatry 14:1139705. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1139705

Received: 07 January 2023; Accepted: 11 May 2023;

Published: 26 May 2023.

Edited by:

Panagiotis Ferentinos, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceReviewed by:

Yan Zhao, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Li, Liu, Wang, Zhou and Yuan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ti-Fei Yuan, eXRmMDcwN0AxMjYuY29t; Dong-Sheng Zhou, d3l6aG91ZHNAc2luYS5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.