- 1Laureate Institute for Brain Research, Tulsa, OK, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, United States

- 3Oxley College of Health Sciences, The University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK, United States

- 4Research Center for Child Mental Development, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan

Background: Adolescents have experienced increases in anxiety, depression, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic and may be at particular risk for suffering from long-term mental health consequences because of their unique developmental stage. This study aimed to determine if initial increases in depression and anxiety in a small sample of healthy adolescents after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic were sustained at follow-up during a later stage of the pandemic.

Methods: Fifteen healthy adolescents completed self-report measures at three timepoints (pre-pandemic [T1], early pandemic [T2], and later pandemic [T3]). The sustained effect of COVID-19 on depression and anxiety was examined using linear mixed-effect analyses. An exploratory analysis was conducted to investigate the relationship between difficulties in emotion regulation during COVID-19 at T2 and increases in depression and anxiety at T3.

Results: The severity of depression and anxiety was significantly increased at T2 and sustained at T3 (depression: Hedges’ g [T1 to T2] = 1.04, g [T1 to T3] = 0.95; anxiety: g [T1 to T2] = 0.79, g [T1 to T3] = 0.80). This was accompanied by sustained reductions in positive affect, peer trust, and peer communication. Greater levels of difficulties in emotion regulation at T2 were related to greater symptoms of depression and anxiety at T3 (rho = 0.71 to 0.80).

Conclusion: Increased symptoms of depression and anxiety were sustained at the later stage of the pandemic in healthy adolescents. Replication of these findings with a larger sample size would be required to draw firm conclusions.

1. Introduction

Emerging literature shows that the rapid spread of COVID-19 has profoundly affected mental health in the general population, with reports indicating higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and even increased cases of stereotyping and discrimination (1–3). These effects are also seen in adolescent populations (4–7). Because adolescence is a sensitive psychosocial developmental period during which symptoms of mental illness may begin to appear, children and adolescents may be at particular risk for suffering from poor mental health as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic (8). Furthermore, adolescents may be at increased risk for decline in mental health due to increased isolation, increased exposure to parents’ mental health issues, disrupted routines as a result of Safer-at-Home orders, loss of milestones (e.g., graduation, homecoming) and schools switching to remote learning (9–11). Studies have identified that females, adolescents with pre-existing mental health conditions, and adolescents with low family support were the most at risk for increased depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic (12–14). Moreover, there is some evidence of an increased risk for familial violence during the pandemic (15).

In our previous report (7), we examined mental health symptoms among psychiatrically healthy adolescents and adolescents with histories of early life stress prior to and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Contrary to our hypotheses, we found that depression and anxiety symptoms were increased in healthy adolescents, whereas adolescents with histories of early life stress demonstrated no significant changes in already elevated symptoms (7). We reasoned that adolescents exposed to early life stress might not show elevated depression and anxiety as a result of their pre-existing chronic stress exposure, or the pandemic may have resulted in potentially buffering changes for those high-risk adolescents (e.g., enhanced feelings of closeness with family members, reduction in social obligations, etc.) (16); however, the pandemic may have significantly affected mental health, especially for adolescents without any pre-existing mental health conditions. Although a growing number of studies show acute changes in adolescent depression and anxiety at the onset of the pandemic (17–19), those have not documented whether changes are later sustained. Moreover, prior research reported that one’s ability to regulate their emotion plays an important role in determining the impact of unexpected crises on youth and adolescents (20, 21). The ability to regulate one’s emotion (i.e., emotion regulation) includes multiple processes such as monitoring, evaluating, modulating, and managing emotional experiences to achieve one’s goal (22, 23). Adolescent’s ability to regulate their emotions can be influenced by their previous interactions with the social environment (e.g., attachment, socialization processes, peer interactions, etc.) as well as their developmental stage (24, 25). Thus, individual differences in emotion regulation may be one of the important variables influencing adolescents’ mental health as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study focused on psychiatrically healthy adolescents and sought to evaluate adolescent depression and anxiety at three separate time points: pre-COVID-19 pandemic (August–December 2019; T1), after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (June 2020; T2), and at a later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2021; T3). For a detailed description of the three stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as cases of COVID-19 and COVID-19 restrictions, please refer to Methods section 2.3. We hypothesized that adolescent depression and anxiety would be increased after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (T2) and sustained at the later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (T3; primary outcomes). We also hypothesized that adolescent peer relationships, as well as mood state (i.e., positive and negative mood states), would be worsened after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (T2) and sustained at the later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (T3; secondary outcomes). Finally, we explored whether increased levels of depression and anxiety at the later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic would be associated with peer relationships and difficulties in emotion regulation, or recognizing and managing affect (26), during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (exploratory outcomes).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Psychiatrically healthy adolescents were eligible for the present study as part of a greater longitudinal investigation of (1) mood, anxiety, and stress disorders in adolescents [Neuroscience-Based Mental Health Assessment and Prediction for Adolescents (NeuroMAP-A)] and (2) the effects of real-time functional magnetic resonance imaging neurofeedback during mindfulness on adolescent resilience [Augmented Mindfulness Training for Resilience in Early Life (A-MindREaL)]. Both projects were funded by the National Institute for General Medical Sciences Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (CoBRE) grant (1P20GM121312). Adolescents were recruited from the community using a school messaging platform (PeachJar), radio adverts, billboards, social network posts, news broadcasting, community presentations, word of mouth, and other miscellaneous methods. Eligibility was determined using a phone screen and remote and in-person visits with caregivers providing demographic information, medical and psychiatric history, pubertal status, and an MRI safety questionnaire. To be eligible for the present study, participants were required to be between 13 and 17 years of age at the time of study enrollment, fluent in English, have access to telephone, and have a consenting parent or guardian. Adolescents were excluded from participating for the following reasons: past or current psychiatric illness, endorsing two or more types of maltreatment on the Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure Scale (MACE) (27), meeting the cutoff score on one or more of the five subscales on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (28), current use of medications affecting blood flow to the brain or brain function (i.e., methylphenidate, antipsychotics, acne medications), history of neurological disorders, magnetic resonance imaging contraindications, unwillingness or inability to complete major aspects of the study protocol, claustrophobia, non-correctable vision, hearing, or sensorimotor impairments, weight below 100 lbs.

2.2. Procedures

During a remote visit, a trained research assistant explained the purpose of the study and study procedures to eligible adolescents and caregivers, who then provided informed assent and consent, respectively, and electrically signed those documents. Procedures were approved by the Western Institutional Review Board. Fifteen adolescents completed online surveys pre-COVID-19 pandemic (T1) and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (T2), and 13 adolescents completed online surveys at a later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (T3). Of those 15 adolescents, zero reported that they and their household members had tested positive for or been diagnosed with COVID-19 at T2, and one reported that a non-household member had been diagnosed with COVID-19 at T2.

2.2.1. Primary outcomes

The severity of depression was measured using the pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-Depression (29–32), and the severity of anxiety was measured by the pediatric PROMIS-Anxiety. The pediatric version of the PROMIS-Depression and -Anxiety were clinically validated through confirmatory factor analysis (confirming two factors: depression and anxiety) and item response theory (32). A T-score of 50 is the average for the United States general youth population with a standard deviation (SD) of 10. A higher T-score represents greater depression or anxiety severity, with a T-score between 55 and 60 indicating mild, 60–70 indicating moderate, and over 70 indicating severe depression or anxiety (33). In the present sample, the PROMIS had high internal consistency within each subscale (depression: ⍺ = 0.91, anxiety: ⍺ = 0.92).

2.2.2. Secondary outcomes

The child version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS-C) (34) was used to measure positive and negative affect. Positive affect refers to the propensity to experience positive emotions and expressions such as joy, cheerfulness, or calmness, and negative affect refers to the propensity to experience negative emotions such as anger, fear, or sadness. The PANAS-C demonstrated good convergent and discriminant validity (34). In the present sample, the PANAS-C had high internal consistency within each subscale (positive affect: ⍺ = 0.94, negative affect: ⍺ = 0.90).

Peer relationships were assessed using the peer version of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment-Revised (IPPA-R) for Children (35). Peer trust refers to the adolescents’ trust that their peers respect and understand their needs and goals; peer communication refers to adolescents’ perceptions that peers are responsive to their emotional states, as well as assessing the amount and quality of verbal communication with them; and peer alienation refers to adolescents’ feelings of isolation, anger, and detachment experienced in relationships with peers (36). The IPPA-R demonstrated adequate to good internal consistency and adequate convergent validity (35). We used peer trust and peer communication subscales since the peer alienation subscale revealed poor internal consistency in the current sample (⍺ = 0.49). Peer trust and peer communication subscales showed high internal consistency (peer trust: ⍺ = 0.96, peer communication: ⍺ = 0.90).

2.2.3. Exploratory outcomes

To assess difficulties in emotion regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic, we used the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) (37). The DERS demonstrated high internal consistency, good test–retest reliability, and adequate construct and predictive validity (37). The original scale was adapted for the current study by adding the word “during this pandemic” to each item (e.g., “During this pandemic, I am experiencing my emotions as overwhelming and out of control”). The DERS measures difficulties in emotion regulations in six domains: (1) nonacceptance of emotional responses reflects a tendency to have a non-accepting reaction to one’s own distress; (2) difficulty engaging in goal-directed behavior reflects difficulty in concentrating or accomplishing tasks when experiencing negative emotions; (3) impulse control difficulties refers to difficulty remaining in control of one’s behavior when experiencing negative emotions; (4) lack of emotional awareness reflects a lack of awareness or inattention to emotional responses; (5) limited access to emotion regulation strategies reflects one’s belief that there is little one can do to regulate oneself once upset; and (6) lack of emotional clarity reflects the extent to which an individual knows and is clear about one’s emotions. Higher scores of each subscale indicate more emotion regulation problems in each domain. In the present sample, the DERS had high overall internal consistency (⍺ = 0.96) as well as good internal consistency within each subscale (⍺ ≥ 0.86).

2.2.4. Other COVID-19 related assessments

We also administered the COVID-19 Adolescent Symptom and Psychological Experience Questionnaire (CASPE) (38) and the Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (CRISIS) (39). The summary statements of those scales are available in the Supplementary Table S1.

Primary and secondary outcomes were collected at all three time points, while exploratory outcomes were collected only at T2.

2.3. COVID-19 context

The present study was conducted in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The first case of COVID-19 in Oklahoma was announced on March 7th, 2020. The WHO categorized the disease as a worldwide pandemic on March 11th of the same year. Public schools began announcing closures on March 20th, and the city of Tulsa issued “Safer-at-Home” orders on the 28th. These included the closure of non-essential businesses and encouraging solely essential trips from the household. These orders applied to all Tulsa residents. Cases of COVID-19 and attributed deaths continued to rise, and by the conclusion of data collection for the second timepoint in June 2020, the total number of infections was 9,354 and deaths was 366. Notably, all COVID-19 restrictions were lifted by June 1st. Surveys for the second timepoint of the present study were administered on May 22, 2020, and completed by June 18th, 2020. Between baseline assessments and timepoint 2, participants had experienced the pandemic onset, a shelter-in-place order, increasing local cases, and eventually reopening. The first COVID-19 vaccine was approved in December of 2020 and was slowly made available to the community in the following months. Follow-up surveys (T3) were administered and completed in March of 2021. By this point, local schools had reopened, and many adopted a hybrid model, transitioning to virtual learning in the event of rising infections in the school. Near the conclusion of data collection in February 2021, there had been 69,112 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Tulsa county and 661 deaths (40).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.0. Linear mixed-effect analyses (LME: lme4 package (41)) were conducted to examine the change in primary and secondary outcomes. The LME model included a fixed effect of time (T1, T2, and T3) and a subject as a random effect. Post-hoc comparisons were conducted with Tukey’s method for the primary outcomes. Next, Spearman’s partial correlations were calculated to investigate the relationship between symptoms of depression and anxiety at T3 and peer trust, peer communication, and difficulties in emotion regulation at T2, controlling for symptoms of depression and anxiety at T1. p-values for the correlation analysis were corrected with the false discovery rate (FDR).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and COVID-19 pandemic-related experiences

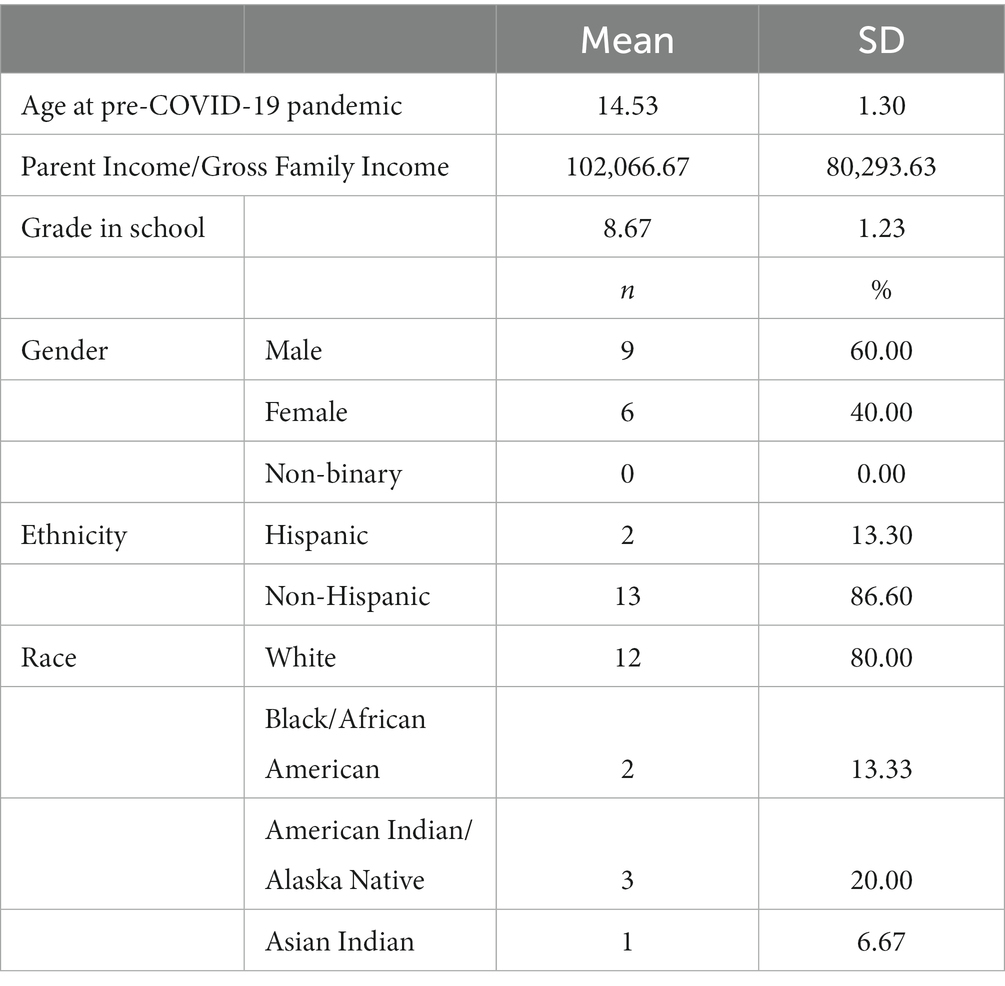

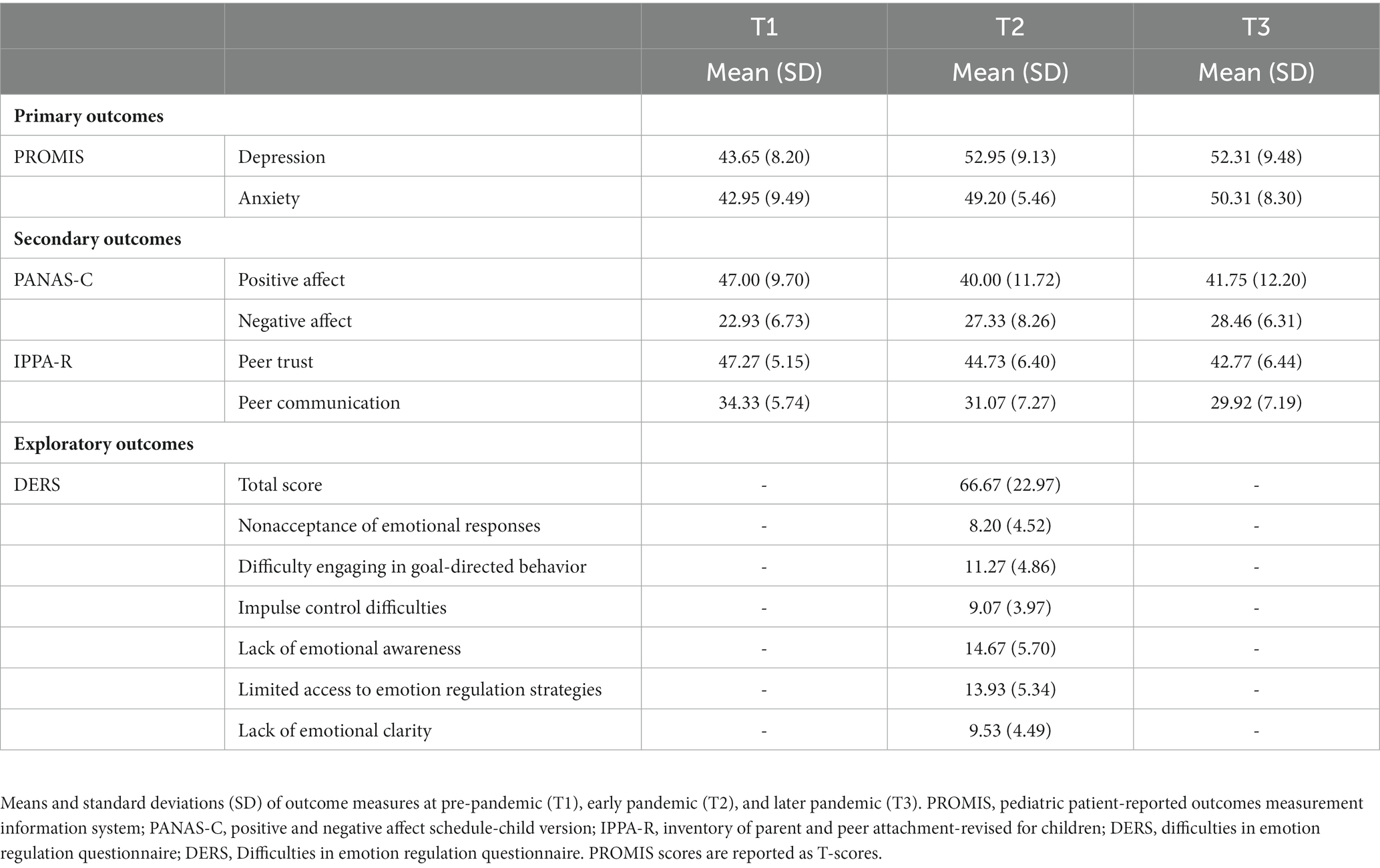

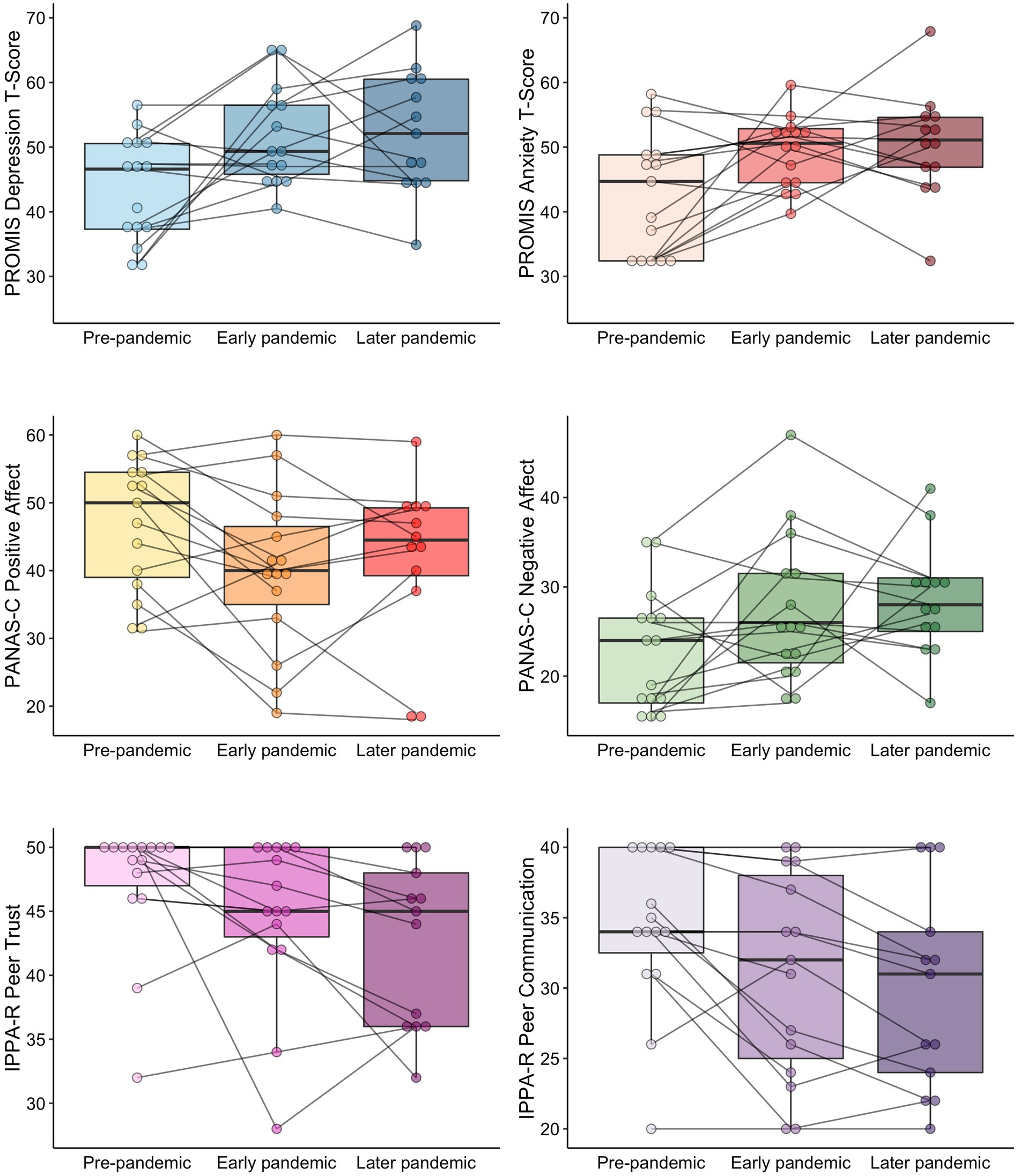

Demographics of participants and the summary of the COVID-19 pandemic-related experiences are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1, respectively, and changes in outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Individual and box plots of the primary and secondary outcomes are illustrated in Figure 1.

3.2. Changes in primary outcomes

3.2.1. Depression

There was a significant time effect on PROMIS depression T-scores [F(2, 27.16) = 5.28, p = 0.01, R2 = 0.20]. A post-hoc analysis revealed increases in symptoms of depression from T1 to T2 (z = 2.95, p = 0.01, Hedges’ g = 1.04), which were maintained at T3 (T1 to T3: z = 2.62, p = 0.02, g = 0.95; T2 to T3: z = −0.22, p = 0.97, g = −0.07). Based on the T-score at T3, 38% of our sample were still experiencing mild levels of depression, while 40% showed mild levels of depression at T2.

3.2.2. Anxiety

There was a significant time effect on PROMIS anxiety T-score [F(2, 26.37) = 5.30, p = 0.012, R2 = 0.14]. A post-hoc analysis revealed increases in symptoms of anxiety from T1 to T2 (z = 2.75, p = 0.02, g = 0.79), which were maintained at T3 (T1 to T3: z = 2.85, p = 0.01, g = 0.80; T2 to T3: z = 0.23, p = 0.97, g = 0.16). Based on the T-score at T3, 15% of our sample were still experiencing mild anxiety, while 6% showed mild levels of anxiety at T2.

3.3. Changes In secondary outcomes

3.3.1. Positive affect

There was a significant time effect on PANAS positive affect [F(2, 25.66) = 4.86, p = 0.02, R2 = 0.08]. A post-hoc analysis revealed reductions in positive affect from T1 to T2 (z = −2.96, p = 0.01, g = −0.63), which were maintained at T3 (T1 to T3: z = −2.24, p = 0.06, g = −0.47; T2 to T3: z = 0.49, p = 0.88, g = 0.14).

3.3.2. Negative affect

There was a trend-wise significant time effect on PANAS negative affect [F(2, 25.98) = 3.04, p = 0.06, R2 = 0.09]. A post-hoc analysis revealed a trend-wise increase in negative affect from T1 to T3 (z = 2.19, p = 0.07, g = 0.82), but not from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3 (T1 to T2: z = 2.04, p = 0.10, g = 0.57; T2 to T3: z = 0.24, p = 0.97, g = 0.15).

3.3.3. Peer trust

There was a significant time effect on IPPA-R peer trust [F(2, 26.65) = 4.31, p = 0.02, R2 = 0.09]. A post-hoc analysis revealed reductions in peer trust from T1 to T3 (z = −2.91, p = 0.01, g = −0.76), while there was no significant difference between T1 to T2 and T2 and T3 (T1 to T2: z = −1.74, p = 0.19, g = −0.42; T2 to T3: z = −1.25, p = 0.42, g = −0.30).

3.3.4. Peer communication

There was a significant time effect on IPPA-R peer communication [F(2, 26.25) = 8.19, p = 0.002, R2 = 0.08]. A post-hoc analysis revealed reductions in peer trust from T1 to T2 (z = −2.81, p = 0.01, g = −0.49), which were maintained at T3 (T1 to T3: z = −3.90, p = 0.001, g = −0.66; T2 to T3: z = −1.23, p = 0.44, g = −0.15).

3.4. Correlations between primary outcomes and exploratory outcomes

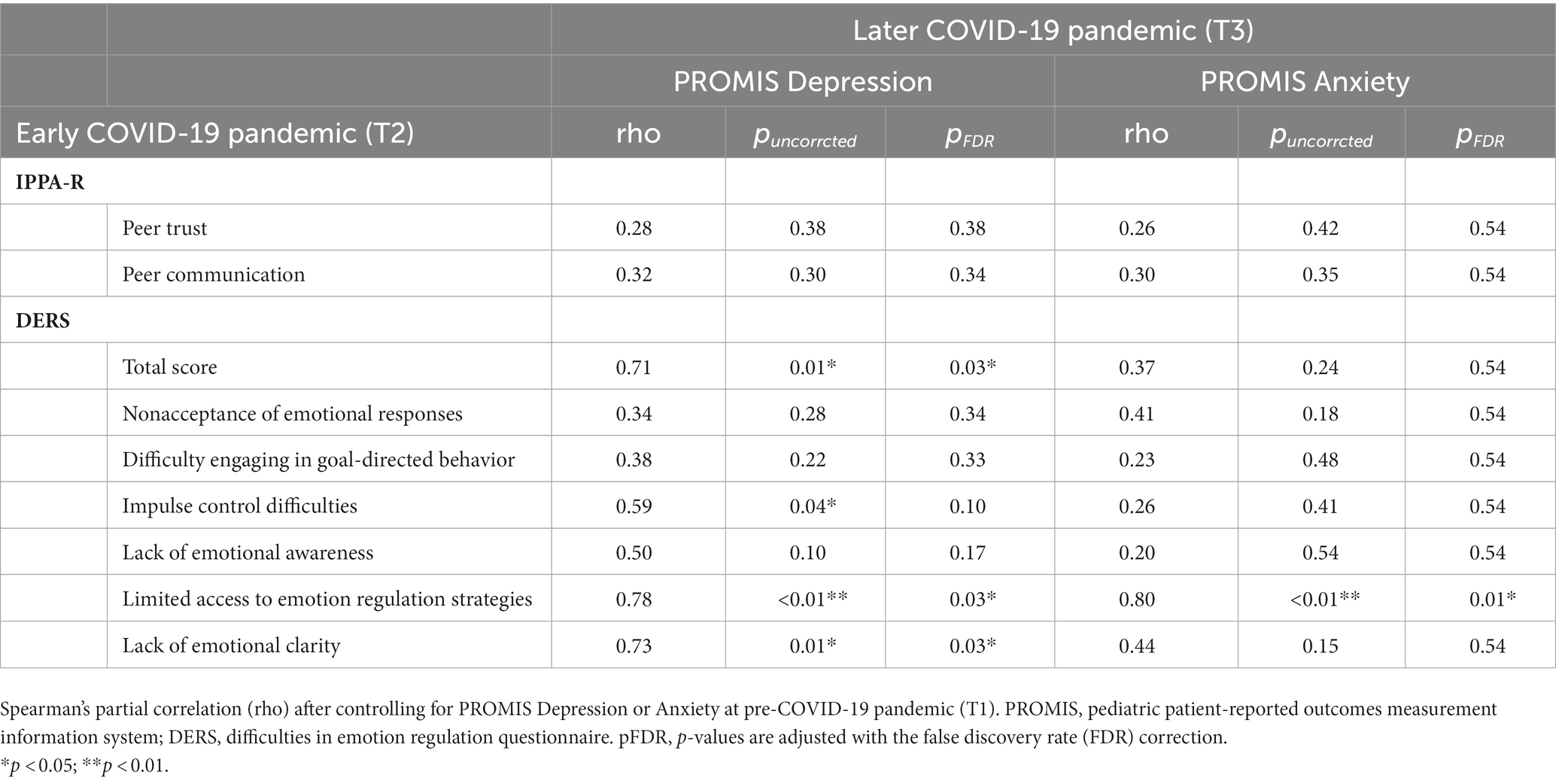

Regardless of the baseline levels of depression and anxiety (T1), greater levels of difficulties in emotion regulation during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (T2) were related to greater symptoms of depression and anxiety at the later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (T3) (Table 3; rho = 0.71 to 0.80, p-FDR < 0.05). Especially, limited access to emotion regulation strategies at T2 was strongly correlated with both depression and anxiety severity at T3 (depression: rho = 0.78, anxiety: rho = 0.80). The relationship between peer trust, peer communication, difficulties in emotion regulation during the early pandemic (T2) and depression and anxiety at the same time point (T2) are summarized in the Supplementary Table S2.

Table 3. Spearman’s partial correlations between difficulties in emotion regulation at the early pandemic (T2) and depression/anxiety severity at the later pandemic (T3).

4. Discussion

Findings from our study are consistent with previous studies reporting sustained increases in anxiety and depression in adolescents as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (42). Research on the longer-term trajectories of mental health symptoms during the first and second years of the COVID-19 pandemic is scarce. Few studies have shown that depression and anxiety symptoms have remained stable at later stages of the pandemic without obvious signs of improvement (43, 44). One study reported that healthy adults experienced sustained increases in levels of depressive and worry symptoms a year after the onset of the pandemic, but adults with psychiatric symptoms did not (43). Our results add preliminary evidence that psychiatrically healthy adolescents may be experiencing heightened depression and anxiety even at a later stage of the pandemic (33). This was accompanied by elevated negative mood as well as lower positive mood. Also, adolescents’ perception of lower levels of peer trust and communication was sustained at the later pandemic.

Although prior studies showed that peer support may help adolescents attain better well-being and address mental health needs (45, 46), in our exploratory analysis, peer relationship at the arly pandemic was not associated with depression and anxiety later in the pandemic. Rather, our results highlight the role of trait emotion regulation. Specifically, adolescents who reported that they had less emotion regulation strategies early in the pandemic were also more likely to later report greater levels of depression and anxiety. Those associations were observed controlling for the baseline levels of depression and anxiety before the onset of the pandemic. A recent study reported that individual differences in emotion regulation difficulties before the pandemic predicted greater COVID-19 acute stress in young adults (47). Our results also supported the notion that emotion regulation may be one of the vulnerabilities increasing risk for developing depression and/or anxiety following an unexpected and uncertain stressful event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Adolescents may benefit from having a flexible and diverse repertoire of emotion regulation strategies under stressful circumstances (47, 48).

It is important to note that emotion regulation skills develop substantially across adolescence. Studies of typically developing individuals indicate that adolescents with limited efficacy of emotion regulation strategies in early adolescence, shift to increased use of adaptive emotion regulations (e.g., emotional clarity, reappraisal, and social support seeking, etc.) and decreased use of maladaptive emotion regulations (e.g., suppression, rumination, and avoidance, etc.) with age (49–52). Therefore, enhancing the development of emotion regulation strategies by teaching adaptive emotion regulation skills such as emotional awareness, acceptance, mindfulness, or managing negative feelings with cognitive reappraisal can help adolescents better regulate their emotions and thoughts during crisis. Additionally, there are individual differences such as sex, pubertal stage, and cognitive ability that need to be considered in understanding how emotion regulation skills develop. Future research may be interested in building individualized materials to teach adaptive emotion regulation skills, depending on those factors since they have been mentioned as having an effect on the connection between emotion regulation and psychopathology (52–56).

5. Limitations

The availability of pre-pandemic data and the longitudinal design of the present study provides the opportunity for interesting analyses; however, we are limited by the small sample size (n = 15). Especially, the exploratory correlational analysis needs to be interpreted with caution since the analyses are correlational, and the results could have been influenced by other variables. Results from the present study should be replicated with larger sample sizes. Moreover, the timing of the later stage of COVID-19 was not strictly defined but rather based on the COVID restrictions and regulations in the Tulsa county area, while several studies defined the second year of the pandemic or February to March 2021 as the later pandemic (43, 44).

6. Conclusion

The present study indicates that psychiatrically healthy adolescents may be experiencing a sustained increase in depression and anxiety symptoms at later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. We further provide preliminary results of the relationship between emotion regulation and the later course of depression and anxiety. These findings indicate a potential need to offer flexible and diverse repertoire of emotion regulation strategies for adolescents in the face of unexpected stressful events.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by WCG IRB. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

GC, ZC, MP, AT, and NK: conceptualization and methodology. GC, AT, and NK: formal analysis. GC and AT: writing – original draft. ZC, MP, and NK: writing – review and editing. MP and NK: supervision and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work has been supported in part by the Laureate Institute for Brain Research, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Center Grant Award Number (1P20GM121312). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to CoBRE NeuroMap Investigators at LIBR, and thank all the research participants and their parents. We acknowledge the contributions of Sahib S. Khalsa, Salvador M. Guinjoan, Tim Collins, Dara Crittenden, Amy Peterson, Megan Cole, Lisa Kinyon, Lindsey Bailey, Courtney Boone, Natosha Markham, Lisa Rillo, Angela Yakshin, and the LIBR Assessment Team for diagnostic assessments and data collection.

Conflict of interest

MP is an advisor to Spring Care, Inc., a behavioral health startup, he has received royalties for an article about methamphetamine in UpToDate.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1137842/full#supplementary-material

References

1.Hahad, O, Gilan, DA, Daiber, A, and Münzel, T. Bevölkerungsbezogene psychische Gesundheit als Schlüsselfaktor im Umgang mit COVID-19. Gesundheitswesen. (2020) 82:389–91. doi: 10.1055/a-1160-5770

2.Lima, CKT, Carvalho, PM d M, Lima, I d AAS, JVA de O, N, Saraiva, JS, de Souza, RI, et al. The emotional impact of coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112915. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112915

3.Salari, N, Hosseinian-Far, A, Jalali, R, Vaisi-Raygani, A, Rasoulpoor, S, Mohammadi, M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. (2020) 16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

4.de Figueiredo, CS, Sandre, PC, Portugal, LCL, Mázala-de-Oliveira, T, da Silva, CL, Raony, Í, et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 106:110171. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171

5.O’Sullivan, K, Clark, S, McGrane, A, Rock, N, Burke, L, Boyle, N, et al. A qualitative study of child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1062. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031062

6.Panchal, U, Salazar de Pablo, G, Franco, M, Moreno, C, Parellada, M, Arango, C, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021):1–27. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w

7.Cohen, ZP, Cosgrove, KT, DeVille, DC, Akeman, E, Singh, MK, White, E, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health: preliminary findings from a longitudinal sample of healthy and at-risk adolescents. Front Pediatr. (2021) 9:622608. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.622608

8.Zolopa, C, Burack, JA, O’Connor, RM, Corran, C, Lai, J, Bomfim, E, et al. Changes in youth mental health, psychological wellbeing, and substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review. Adolesc Res Rev. (2022) 7:161–77. doi: 10.1007/s40894-022-00185-6

9.Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2020) 4:421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7

10.Van Lancker, W, and Parolin, Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: a social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e243–4. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0

11.Gruber, J, Clark, LA, Abramowitz, JS, Aldao, A, Chung, T, Forbes, EE, et al. Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am Psychol. (2021) 76:409–26. doi: 10.1037/amp0000707

12.Hafstad, GS, Sætren, SS, Wentzel-Larsen, T, and Augusti, E-M. Adolescents’ symptoms of anxiety and depression before and during the Covid-19 outbreak – a prospective population-based study of teenagers in Norway. Lancet Reg Health - Eur. (2021) 5:100093. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100093

13.Magson, NR, Freeman, JYA, Rapee, RM, Richardson, CE, Oar, EL, and Fardouly, J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. (2021) 50:44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

14.Oosterhoff, B, Palmer, CA, Wilson, J, and Shook, N. Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 67:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004

15.Humphreys, KL, Myint, MT, and Zeanah, CH. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. (2020) 146:e20200982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982

16.Radka, K, Wyeth, EH, and Derrett, S. A qualitative study of living through the first New Zealand COVID-19 lockdown: affordances, positive outcomes, and reflections. Prev Med Rep. (2022) 26:101725. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101725

17.Chen, F, Zheng, D, Liu, J, Gong, Y, Guan, Z, and Lou, D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:36–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061

18.Hawes, MT, Szenczy, AK, Klein, DN, Hajcak, G, and Nelson, BD. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. (2022) 52:3222–30. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005358

19.Racine, N, McArthur, BA, Cooke, JE, Eirich, R, Zhu, J, and Madigan, S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. (2021) 175:1142–50. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

20.Jenness, JL, Jager-Hyman, S, Heleniak, C, Beck, AT, Sheridan, MA, and McLaughlin, KA. Catastrophizing, rumination, and reappraisal prospectively predict adolescent PTSD symptom onset following a terrorist attack. Depress Anxiety. (2016) 33:1039–47. doi: 10.1002/da.22548

21.Terranova, AM, Boxer, P, and Morris, AS. Factors influencing the course of posttraumatic stress following a natural disaster: children’s reactions to hurricane Katrina. J Appl Dev Psychol. (2009) 30:344–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.017

22.Thompson, RA. Emotion regulation: a theme in search of definition. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. (1994) 59:25–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01276.x

23.Gross, JJ. Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychol Inq. (2015) 26:1–26. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

24.Sroufe, LA. Emotional development: The organization of emotional life in the early years, vol. xiii. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press (1996). 263 p.

25.Zeman, J, Cassano, M, Perry-Parrish, C, and Stegall, S. Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2006) 27:155–68. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604000-00014

26.Ritschel, LA, Tone, EB, Schoemann, AM, and Lim, NE. Psychometric properties of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale across demographic groups. Psychol Assess. (2015) 27:944–54. doi: 10.1037/pas0000099

27.Teicher, MH, and Parigger, A. The ‘maltreatment and abuse chronology of exposure’ (MACE) scale for the retrospective assessment of abuse and neglect during development. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0117423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117423

28.Bernstein, DP, Stein, JA, Newcomb, MD, Walker, E, Pogge, D, Ahluvalia, T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2003) 27:169–90. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

29.Cella, D, Riley, W, Stone, A, Rothrock, N, Reeve, B, Yount, S, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. (2010) 63:1179–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011

30.DeWalt, DA, Rothrock, N, Yount, S, and Stone, AA. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. (2007) 45:S12–21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2

31.Walsh, TR, Irwin, DE, Meier, A, Varni, JW, and DeWalt, DA. The use of focus groups in the development of the PROMIS pediatrics item bank. Qual Life Res. (2008) 17:725–35. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9338-1

32.Irwin, DE, Stucky, B, Langer, MM, Thissen, D, DeWitt, EM, Lai, J-S, et al. An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Qual Life Res. (2010) 19:595–607. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9619-3

33.Kaat, AJ, Kallen, MA, Nowinski, CJ, Sterling, SA, Westbrook, SR, and Peters, JT. PROMIS® pediatric depressive symptoms as a harmonized score metric. J Pediatr Psychol. (2019) 45:271–80. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsz081

34.Laurent, J, Catanzaro, SJ, Joiner, TE Jr, Rudolph, KD, Potter, KI, Lambert, S, et al. A measure of positive and negative affect for children: scale development and preliminary validation. Psychol Assess. (1999) 11:326–38. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.326

35.Gullone, E, and Robinson, K. The inventory of parent and peer attachment—revised (IPPA-R) for children: a psychometric investigation. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2005) 12:67–79. doi: 10.1002/cpp.433

36.Guarnieri, S, Ponti, L, and Tani, F. The inventory of parent and peer attachment (IPPA): a study on the validity of styles of adolescent attachment to parents and peers in an Italian sample. TPM-Test Psychom Methodol Appl Psychol. (2010) 17:103–30.

37.Gratz, KL, and Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. (2004) 26:41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

38.Ladouceur, CD (2020). COVID-19 adolescent symptom & psychological experience questionnaire. OSF storage assess COVID-19 Exp ACE Adolesc - res tracker Facil. Available at: https://osf.io/mzrjg [Accessed December 26, 2022]

39.Nikolaidis, A, Paksarian, D, Alexander, L, Derosa, J, Dunn, J, Nielson, DM, et al. The coronavirus health and impact survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:8139. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87270-3

40.City of Tulsa (2021). https://www.cityoftulsa.org/press-room/coronavirus-tulsa-covid-19-update-feb-18/

41.Bates, D, Mächler, M, Bolker, B, and Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. (2014) 67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

42.Ravens-Sieberer, U, Erhart, M, Devine, J, Gilbert, M, Reiss, F, Barkmann, C, et al. Child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of the three-wave longitudinal COPSY study. J Adolesc Health. (2022) 71:570–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.06.022

43.Kok, AAL, Pan, K-Y, Rius-Ottenheim, N, Jörg, F, Eikelenboom, M, Horsfall, M, et al. Mental health and perceived impact during the first Covid-19 pandemic year: a longitudinal study in Dutch case-control cohorts of persons with and without depressive, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. J Affect Disord. (2022) 305:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.02.056

44.Patel, K, Robertson, E, Kwong, ASF, Griffith, GJ, Willan, K, Green, MJ, et al. Psychological distress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among adults in the United Kingdom based on coordinated analyses of 11 longitudinal studies. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e227629. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7629

45.Schmidt, A, Dirk, J, and Schmiedek, F. The importance of peer relatedness at school for affective well-being in children: between- and within-person associations. Soc Dev. (2019) 28:873–92. doi: 10.1111/sode.12379

46.Suresh, R, Alam, A, and Karkossa, Z. Using peer support to strengthen mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:7147181. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714181

47.Tyra, AT, Griffin, SM, Fergus, TA, and Ginty, AT. Individual differences in emotion regulation prospectively predict early COVID-19 related acute stress. J Anxiety Disord. (2021) 81:102411. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102411

48.Aldao, A, Sheppes, G, and Gross, JJ. Emotion regulation flexibility. Cogn Ther Res. (2015) 39:263–78. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9662-4

49.Zimmermann, P, and Iwanski, A. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. Int J Behav Dev. (2014) 38:182–94. doi: 10.1177/0165025413515405

50.Gullone, E, Hughes, EK, King, NJ, and Tonge, B. The normative development of emotion regulation strategy use in children and adolescents: a 2-year follow-up study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2010) 51:567–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02183.x

51.Schäfer, JÖ, Naumann, E, Holmes, EA, Tuschen-Caffier, B, and Samson, AC. Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: a meta-analytic review. J Youth Adolesc. (2017) 46:261–76. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0585-0

52.McRae, K, Gross, JJ, Weber, J, Robertson, ER, Sokol-Hessner, P, Ray, RD, et al. The development of emotion regulation: an fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal in children, adolescents and young adults. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. (2012) 7:11–22. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr093

53.Wante, L, Mezulis, A, Van Beveren, M-L, and Braet, C. The mediating effect of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies on executive functioning impairment and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Child Neuropsychol. (2017) 23:935–53. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2016.1212986

54.Alloy, LB, Hamilton, JL, Hamlat, EJ, and Abramson, LY. Pubertal development, emotion regulatory styles, and the emergence of sex differences in internalizing disorders and symptoms in adolescence. Clin Psychol Sci. (2016) 4:867–81. doi: 10.1177/2167702616643008

55.Krause, ED, Vélez, CE, Woo, R, Hoffmann, B, Freres, DR, Abenavoli, RM, et al. Rumination, depression, and gender in early adolescence: a longitudinal study of a bidirectional model. J Early Adolesc. (2018) 38:923–46. doi: 10.1177/0272431617704956

Keywords: depression, anxiety, adolescent, COVID-19, mental health, emotion regulation

Citation: Cochran G, Cohen ZP, Paulus MP, Tsuchiyagaito A and Kirlic N (2023) Sustained increase in depression and anxiety among psychiatrically healthy adolescents during late stage COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1137842. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1137842

Edited by:

Amir Garakani, Yale Medicine, United StatesReviewed by:

Ahmet Özaslan, Gazi University, TürkiyeRahul Suresh, McGill University Health Centre, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Cochran, Cohen, Paulus, Tsuchiyagaito and Kirlic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aki Tsuchiyagaito, YXRzdWNoaXlhZ2FpdG9AbGF1cmVhdGVpbnN0aXR1dGUub3Jn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Gabe Cochran

Gabe Cochran Zsofia P. Cohen

Zsofia P. Cohen Martin P. Paulus

Martin P. Paulus Aki Tsuchiyagaito

Aki Tsuchiyagaito Namik Kirlic

Namik Kirlic