- 1Department of Community Health and Psychiatry, The University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica

- 2Caribbean Institute of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, The University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica

- 3Kingston Public Hospital, Kingston, Jamaica

- 4Department of Sociology, Psychology and Social Work, The University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica

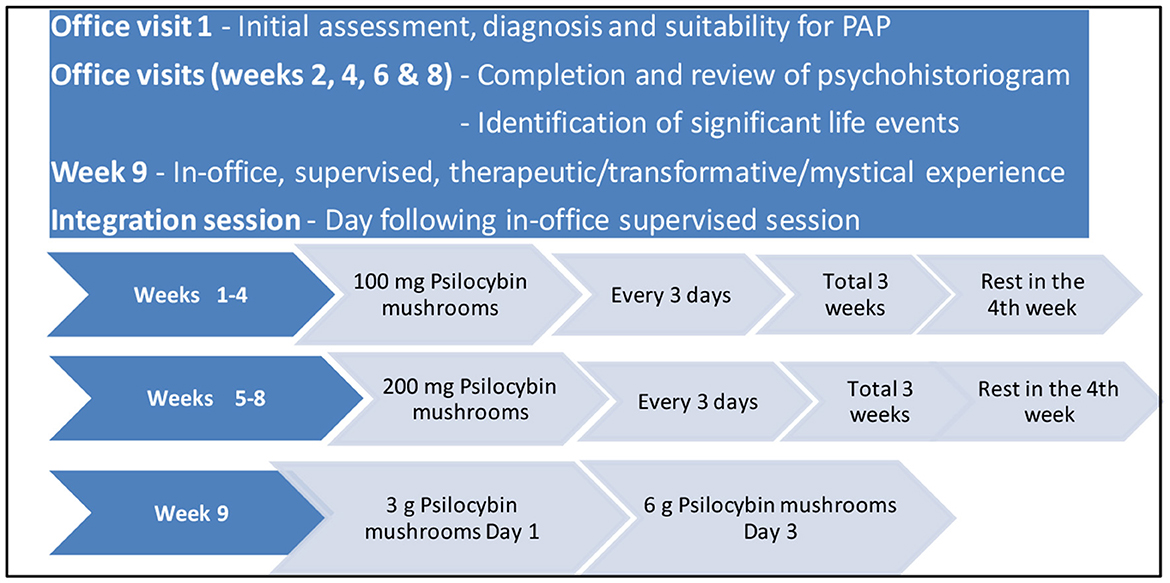

The efficacy of psilocybin and other psychedelics as modes of treatment have been demonstrated through clinical trials and other studies in the management of a number of mental illnesses, including some treatment resistant cases. In Psychedelic Assisted Psychotherapy (PAP), psychedelics catalyze or enhance the experience fostered by psychotherapeutic methods. Psychohistoriographic Brief Psychotherapy, conceptualized by the late Professor Frederick Hickling in the 1970′s in Kingston, Jamaica, offers a pathway for exploration in the Jamaican context. Applied to individuals, Psychohistoriographic Brief Therapy (PBT) has already shown success in patients with personality disorders in Jamaica through a process which includes documenting life experiences in a psychohistoriogram. In the De La Haye psilocybin Treatment Protocol (DPTP), micro-doses of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms are taken throughout an 8-week outpatient process of documenting the components of the psychohistoriogram, making use of the increased openness and empathy associated with the use of psychedelic agents. These sessions are followed by supervised in-office therapeutic/mystical doses of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms in the 9th week. Given the legal status and availability of psilocybin containing products in a few countries like Jamaica, there is a potential role for a regulated psychedelic industry contributing to the body of useful and rigorous clinical research which is needed in this area. Clients could benefit as we venture into this new frontier in psychiatry.

Introduction

Psychedelic Assisted Psychotherapy (PAP), the new frontier in psychiatry (1) has seen a resurgence in interest over the last two decades and is poised for further growth in the treatment of mental illnesses (2, 3). Numerous studies have demonstrated the clinical efficacy of psychedelics in the effective management of treatment resistant depression (4–9), post-traumatic stress disorder (10, 11), anxiety disorder (12), substance use disorder (13, 14), obsessive-compulsive disorders (15), and existential distress (7, 16). With demonstrable effects in varying patient populations, there has been remarkable renewed promise for the use of psychedelics in the treatment of mental illnesses (17). Psychedelics facilitate increased interconnectivity within the brain, a concept referred to as the “entropic brain” by Carhart-Harris (18, 19), while down regulating adverse and traumatic experiences, creating new neural connections and “resetting” the brain (18, 19).

While the active psychedelic compound psilocin was originally isolated in 1958, the use of psychedelics has a long history. Mesoamerican cultures referred to psychedelic rituals before the arrival of Columbus (20, 21). Psychedelics related research was dramatically and hastily discontinued following concerns about recreational drug use and the rise of the “counterculture movement” in the United States of America (U.S.A) (22). This led to their subsequent classification as Schedule I compounds, which are substances with a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use (23, 24).

Promising results from recent research have led researchers to explore the phenomenon of psychedelics used in conjunction with the utilization of various psychotherapeutic techniques, giving rise to the term Psychedelic Assisted Psychotherapy (PAP). A few studies have shown that PAP may be effective, even for patients considered “treatment resistant” (25). Varying psychotherapeutic modalities have been employed to provide psychological support comprising non-directive preparation, support, and integration, via both individual and group counseling (26–29). An increased focus on identifying ideal modalities for and frequency of psychotherapeutic interventions may help improve outcomes with PAP. While the exact mechanisms by which psilocybin and other psychedelics augment the psychotherapeutic experience are still unclear, it is thought that they catalyze or enhance psychotherapeutic processes (30).

One such psychotherapeutic modality, Psychohistoriographic Brief Psychotherapy, was conceptualized by the late Professor Frederick Hickling in the 1970′s at the Bellevue Mental Hospital in Kingston, Jamaica (31). Historiograpy is the philosophy of methodology of history. Psychohistoriography is a post-colonial, Caribbean model of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy for groups and individuals that addresses multiculturalism, conflict resolution, insight, and social change. It is a psychological method devised for the promotion of insight in psychotherapy, using history as the engine of growth in the therapeutic milieu. Psychohistoriographic Brief Psychotherapy was developed around a technique of life-history mapping, where individual memories, including significant life events are documented around a timeline within a dialectic matrix called the psychohistoriogram. These dialectic antipodes include family events (mother & father), social learning (education & environmental), activity life events (religion and work), cultural life events (extracurricular & artistic/creative work), affect shaping life events (political and emotional), and psychosexual life events (sexual and social). The patient charts these historical facts in line with the associated life parameter. Psychohistoriographic Brief Psychotherapy grew out of the large group technique of Psychohistoriographic Cultural Therapy. It is grounded in the dialectic historical experience of the Caribbean and Caribbean people (31–33). This exploration of memories and events over time, guided by the therapist results in the creation of a poetic script that captures the insight and the journey in arriving at said insight in a tangible form that can be documented for reflection. The insight, described as the psychic centrality, was best captured by Hickling when he wrote, “Psychic centrality refers to a sense of psychological containment or organization of diverse individual points of view through creating a historical map of collective experience” (34). The Psychohistoriographic Brief Psychotherapy model has had success in patients with personality disorders in Jamaica (35). Hickling's (35) paper presents results from evaluations conducted by the therapist himself with no control group or external evaluation of the results.

The Jamaican setting

Jamaicans have a long history of plant products being readily accepted and preferred for treating various medical conditions (36–39). Historical records and current estimates suggest that this preference and willingness to rely on traditional healing modalities, including herbal remedies for treating medical conditions has continued in our culture for many years (40). In Jamaica, the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1996 and subsequent revision in 2015 make specific stipulations for raw opium and cocoa leaves, prepared opium, cannabis and cannabis containing compounds, and derivates specifically Cocaine and Morphine. There is no current legislative framework governing the possession or use of psilocybin or products containing psilocybin within Jamaica, despite Jamaica being a signatory to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, and the subsequent Convention on Psychotrophic Substance of 1971, since 6th October 1989.

In Jamaica patients with mental health conditions requiring specialist care may be referred by their family physician to private Psychiatrists, though some patients also present and are seen without referrals. In the last 12 months, adult patients voluntarily presenting to the first author's private psychiatric practice setting in Kingston, Jamaica have been provided with the option of using psilocybin products for the treatment of major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders and existential distress. This has been a welcomed addition to the treatment options being provided in this private psychiatric setting, which also provides conventional/traditional forms of pharmacological treatment of these conditions.

Adult patients participate in individual PAP sessions with the exploration of personal memories and significant life events, documenting these in the aforementioned matrix called the psychohistoriogram, making use of the increased openness and empathy associated with the use of psychedelic agents (41–43). Patients are introduced to the De La Haye psilocybin Treatment Protocol (Figure 1), with the option of commencing microdoses of capsule containing crushed psilocybin containing mushroom products on an outpatient basis, escalating to optional in office, supervised, individual therapeutic/transformative/mystical experience doses. Over 40 patients have been managed with this method, with the results/outcomes of these being collated for publication. This number of patients includes some who were previously being managed on conventional antidepressants, diagnosed as treatment resistant, but also some who indicated that they wanted to try this alternative method of treatment for indicated conditions, as they hoped to feel even better than they had been, based on their own research findings on the potential effects of psilocybin in the treatment of some mental health conditions. One patient expressed her hope to at least be able to cut down on her antidepressant dosage as she “does not feel real”.

These patients are being followed up and have all expressed their satisfaction with having the opportunity to access this option of treatment locally, and in a legal, private psychiatric treatment facility. They have also reported their preference for having one-on-one treatment in a private setting of this nature, as opposed to having to share personal experiences in a group type retreat setting, a format which has also been available in Jamaica. Many have expressed their willingness to encourage others to participate in this protocol, where indicated, but have also expressed their concern that products like psilocybin are not available to the average patient who may be unable to participate in private psychiatric management.

The De La Haye psilocybin Treatment Protocol

The De La Haye psilocybin Treatment Protocol (DPTP) (Figure 1), developed by addiction psychiatrist, Dr. Winston De La Haye consists of a 9-week process of transitioning from out-patient microdoses to in-office, supervised therapeutic/transformative/mystical experience doses of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms. Microdoses (100 mg capsules) of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms are taken once every 3 days (2 rest days between doses) throughout weeks 1–3 of the 8-week outpatient first phase of the protocol. A 1-week break is then taken (week 4), after which 200 mg microdoses (2 × 100 mg capsules) of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms are taken, once every 3 days throughout weeks 5–7. This is followed by a further 1-week break (week 8), which completes the first 8 weeks, first phase of the DPTP protocol where microdoses of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms are taken on an out-patient basis. In this 8-week microdose, first phase of the DPTP documenting the components of the Psychohistoriogram are completed and reviewed with the patient. The optional second phase of the protocol consists of the supervised, in-office administration of higher therapeutic/transformative/mystical doses (3 or 6 g) of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms (1 g per chocolate bar) on days 1 and 3 of the 9th week of the program. An in-office session on the day following the therapeutic/transformative/mystical dose administration completes the integration sessions, where a revisit of the psychohistoriogram is a significant component.

At their first in-office session, patients present a thorough history and are assessed to determine their diagnosis and suitability for PAP (Figure 1). Those desirous of using this treatment modality are introduced to the concept of Psychohistoriography and guided over the next 2 visits in how to document their histories in the different domains discussed above. Patients commence the out-patient microdose component of the DPTP and are followed up with in-office visits at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, as per the DPP (Figure 1). These follow-up sessions include a review of their psychohistoriogram (completed or ongoing), with identification by the therapist of challenging or traumatic life events, documented or reported in their history. In these sessions, patients are provided with continued information on their psilocybin dosages and decisions surrounding continuation in week 9 with a supervised, in-patient mystical/therapeutic dose of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms (3 or 6 g). They are also advised of the possibility of any highlighted challenging/stressful/traumatic events they have documented being a part of their mystical/therapeutic dose psilocybin experience. Patients also report in these follow-up sessions on any adjustment in their presenting symptoms. Those agreeing to participate in the 6 h. (9:00 a.m.−3:00 p.m.) supervised session are seen in-office the day following their high dose experience for a specific integration session. Patients are then followed up on a monthly basis, as necessary.

Psychedelic Assisted Psychotherapy, utilizing the Psychohistoriogram as outlined above, prepares a valuable “target”, based on personal memories and significant life events for focus during the administration of therapeutic/transformative/mystical doses of crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms, facilitating the associated behavioral transformation process resulting fom PAP. Life events charted in the two-dimensional sequence of time and life parameters can be very useful in integration sessions. The crushed, dried psilocybin mushrooms used in the DPTP protocol above are derived from the Psilocybe cubensis species of psychedelic mushrooms, belonging to the fungus family Hymenogastraceae. Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms contain 10–12 mg of psilocybin per gram of dried mushrooms (44). The 8-week microdose period, in addition to facilitating the documentation of the patient's psychohistoriography, also allows for the gradual reduction and eventual discontinuation of antidepressant pharmacotherapy in treatment resistant patients, in addition to facilitating the patient's experience with a new product.

These are interesting times for PAP in the Caribbean in general and Jamaica in particular, benefiting clients as we venture into this new frontier in psychiatry, both in clinical practice and research. We must ensure that the Caribbean's rapidly expanding psychedelic wellness and medical programs are safe, while maintaining the highest ethical standards in the therapeutic use of psychedelics. Given the legal status and availability of psilocybin containing products in a few countries like Jamaica, there is a potential role for a regulated psychedelic industry contributing to the body of useful and rigorous clinical research which is needed in this area.

Author contributions

WD developed the treatment protocol outlined in the manuscript. WD and GW contributed to the conception of the paper. JG and WD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors wrote sections of the manuscript, reviewed the manuscript, contributed to its revision, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

WD was employed as Medical Director by Aion Therapeutic Inc. in 2021. This association ended in 2022.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rucker JJ, Young AH. Psilocybin: from serendipity to credibility? Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:659044. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659044

2. Aday JS, Bloesch EK, Davoli CC. 2019: a year of expansion in psychedelic research, industry, and deregulation. Drug Sci Policy Law. (2020) 6. doi: 10.1177/2050324520974484

3. Ona G, Bouso JC. Psychedelic drugs as a long-needed innovation in psychiatry. Qeios. (2020). doi: 10.32388/T3EM5E

4. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Rucker J, Day CM, Erritzoe D, Kaelen M, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: An open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiat. (2016) 3:7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7

5. Carhart-Harris RL, Roseman L, Bolstridge M, Demetriou L, Pannekoek JN, Wall MB, et al. Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13282-7

6. Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, Cosimano MP, Sepeda ND, Johnson MW, et al. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2021) 78:5. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285

7. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:12. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675513

8. Gukasyan N, Davis AK, Barrett FS, Cosimano MP, Sepeda ND, et al. Efficacy and safety of psilocybin-assisted treatment for major depressive disorder: prospective 12-month follow-up. J Psychopharmacol. (2022) 36:2. doi: 10.1177/02698811211073759

9. Watts R, Day C, Krzanowski J, Nutt D, Carhart-Harris R. Patients' accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Humanist Psychol. (2017) 57:5. doi: 10.1177/0022167817709585

10. Mitchell JM, Bogenschutz M, Lilienstein A, Harrison C, Kleiman S, Parker-Guilbert K, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. (2021) 27:6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

11. Mithoefer MC, Feduccia AA, Jerome L, Mithoefer A, Wagner M, Walsh Z, et al. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of PTSD: Study design and rationale for phase 3 trials based on pooled analysis of six phase 2 randomized controlled trials. Psychopharmacology. (2019) 236:9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-05249-5

12. Grob CS, Danforth AL, Chopra GS, Hagerty M, McKay CR, Halberstadt AL, et al. Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2011) 68:1. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.116

13. Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PC, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol. (2015) 29:3. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565144

14. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2017) 43:1. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135

15. Moreno FA, Wiegand CB, Taitano EK, Delgado PL. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in 9 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2006) 67:11. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n1110

16. Mayer CE, LeBaron VT, Acquaviva KD. Exploring the use of psilocybin therapy for existential distress: a qualitative study of palliative care provider perceptions. J Psychoact Drugs. (2021) 54:1. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2021.1916659

17. Perkins D, Sarris J, Rossell S, Bonomo Y, Forbes D, Davey C, et al. Medicinal psychedelics for mental health and addiction: advancing research of an emerging paradigm. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2021) 55:12. doi: 10.1177/0004867421998785

18. Carhart-Harris RL, Leech R, Hellyer PJ, Shanahan M, Feilding A, Tagliazucchi E, et al. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Front Hum Neurosci. (2014) 8:20. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020

19. Carhart-Harris RL. The entropic brain-revisited. Neuropharmacology. (2018) 142:167–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.03.010

20. Carod-Artal FJ. Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbia Mesoamerican cultures. Neurologia. (2015) 30:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2011.07.010

21. Samorini G. The oldest archeological data evidencing the relationship of Homo sapiens with psychoactive plants: a worldwide overview. J Psychedelic Stud. (2019) 3:2. doi: 10.1556/2054.2019.008

22. Belouin SJ, Henningfield JE. Psychedelics: where we are now, why we got here, what we must do. Neuropharmacology. (2018) 142:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.02.018

23. Nutt D, Erritzoe D, Carhart-Harris R. Psychedelic psychiatry's brave new world. Cell. (2020) 18:24–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.020

24. United Nations Office on Drugs Crime. Convention on Psychotropic Substances. (1971). Available online at: https://www.unodc.org/pdf/convention_1971_en.pdf (accessed December 15, 2022).

25. Schenberg EE. Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: a paradigm shift in psychiatric research and development. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:733. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00733

26. Barrett FS, Robbins H, Smooke D, Brown JL, Griffiths RR. Qualitative and quantitative features of music reported to support peak mystical experiences during psychedelic therapy sessions. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1238. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01238

27. Curtis R, Roberts L, Graves E, Rainey HT, Wynn D, et al. The role of psychedelics and counseling in mental health treatment. J Ment Couns. (2020) 42:4. doi: 10.17744/mehc.42.4.03

28. Griffiths RR, Richards WA, McCann U, Jesse R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology. (2006) 187:3. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5

29. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Richards WA, Richards BD, Jesse R, MacLean KA, et al. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors. J Psychopharmacol. (2018) 32:1. doi: 10.1177/0269881117731279

30. Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, Carpenter LL, Widge AS, Rodriguez CI, et al. Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010035

31. Hickling FW. Sociodrama in the rehabilitation of chronic mentally ill patients. Psychiatr Serv. (1989) 40:4. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.4.402

32. Hickling FW, A. Psycho-historiographic analysis of Claude McKay. Caribb Q. (1992) 38:1. doi: 10.1080/00086495.1992.11671748

33. Hickling FW. Psychohistoriography: A Post-Colonial Psychoanalytic and Psychotherapeutic Model. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press (2012). 234 p.

34. Hickling FW, Guzder J, Robertson-Hickling H, Snow S, Kirmayer, LJ. Psychic centrality: Reflections on two psychohistoriographic cultural therapy workshops in Montreal. Transcult Psychiatry. (2010) 47:136–58. doi: 10.1177/1363461510364590

35. Hickling FW. The treatment of personality disorder in Jamaica with psychohistoriographic brief psychotherapy. West Indian Med J. (2013) 62:5. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2013.093

36. De La Haye W, Walcott G, Eaton J, Greene J, Beckford J. Psychedelics for use and wellbeing cultural context and recent developments: a Jamaican perspective. J Comp Alt Med. (2022) 8. doi: 10.33552/OJCAM.2022.08.000676

37. Adeniyi O, Washington L, Glenn CJ, Franklin SG, Scott A, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among hypertensive and type 2 diabetic patients in Western Jamaica: a mixed methods study. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0245163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245163

38. Delgoda R, Younger N, Barrett C, Braithwaite J, Davis D. The prevalence of herbs use in conjunction with conventional medicines in Jamaica. Comp Ther Med. (2010) 18:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.01.002

39. Picking D, Younger N, Mitchell S, Delgoda R. The prevalence of herbal medicine home use and concomitant use with pharmaceutical medicines in Jamaica. J Ethnopharmacol. (2011) 137:305–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.025

40. Nieves-Rivera ÁM, Muñoz-Vázquez J, Betancourt-López C. Hallucinogens used by Taino Indians in the West Indies. Atenea. (1995) 15:125–41.

41. Kuypers KPC. Out of the box: a psychedelic model to study the creative mind. Med Hypotheses. (2018) 115. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2018.03.010

42. MacLean KA, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. J Psychopharmacol. (2011) 25:11. doi: 10.1177/0269881111420188

43. Hickling FW, Walcott GO. The Jamaican LMIC challenge to the biopsychosocial global mental health model of Western psychiatry. In:Okpaku S, , editor. Innovations in Global Mental Health. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2019). p. 761–77.

Keywords: psilocybin, psychedelics, Psychedelic Assisted Psychotherapy, psychohistoriography, new frontier

Citation: De La Haye W, Walcott G, Eaton J, Beckford J and Greene J (2023) Psychedelic Assisted Psychotherapy preparing your target using psychohistoriography: a Jamaican perspective. Front. Psychiatry 14:1136990. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1136990

Received: 03 January 2023; Accepted: 15 June 2023;

Published: 29 June 2023.

Edited by:

Martin L. Williams, Swinburne University of Technology, AustraliaReviewed by:

Samuli Kangaslampi, Tampere University, FinlandCopyright © 2023 De La Haye, Walcott, Eaton, Beckford and Greene. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Winston De La Haye, d2luc3Rvbi5kZWxhaGF5ZUB1d2ltb25hLmVkdS5qbQ==

Winston De La Haye

Winston De La Haye Geoffrey Walcott

Geoffrey Walcott Jordan Eaton1

Jordan Eaton1 Janelle Greene

Janelle Greene