- 1Department of Maternal and Child Health, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Department of Child Healthcare, Affiliated Foshan Maternity and Child Healthcare Hospital, Southern Medical University, Foshan, China

- 3The Second School of Clinical Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 4School of Mathematics and Statistics, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China

- 5Key Laboratory of Brain, Cognition and Education Science, Ministry of Education, China; Institute for Brain Research and Rehabilitation, and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Mental Health and Cognitive Science, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, China

Background: Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are at high risk of experiencing externalizing and internalizing problems. This study aimed to reveal how maternal parenting styles and autistic traits influence behavioral problems in children with ASD.

Methods: This study recruited 70 2–5 years children with ASD and 98 typically developing (TD) children. The Parental Behavior Inventory (PBI) and Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) were used to collect the maternal parenting styles and autistic traits, respectively. The children’s behavioral problems were reported by the mothers using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Hierarchical moderated regression analyses were used to determine whether maternal autistic traits moderated the association between parenting style and behavioral problems in the children.

Results: Compared to TD children, children with ASD exhibited more severe externalizing and internalizing problems (t = 4.85, p < 0.01). The ASD group scored lower in the maternal supportive/engaged parenting style than the TD group (t = 3.20, p < 0.01). In the TD group, the maternal AQ attention switching domain was positively correlated with internalizing problems in the children (β = 0.30, p = 0.03). In the ASD group, hostile/coercive parenting style was significantly correlated with externalizing problems in the children (β = 0.30, p = 0.02), whereas maternal AQ attention switching domain was negatively correlated with externalizing problems (β = −0.35, p = 0.02). Moreover, the maternal AQ attention switching domain moderated the association between hostile/coercive parenting style and children’s externalizing problems (β = 0.33, p = 0.04).

Conclusion: Among ASD children, a hostile/coercive parenting style can increase the risks of children’s externalizing problems, especially in the context of high levels of maternal attention-switching problems. Hence, the current study has important implications for the clinical practice of early family-level interventions for children with ASD.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a group of neurodevelopmental disorders with different levels of social communication difficulties as well as the presence of restricted interests or stereotyped behaviors (1). Currently, ASD affects 1 in 44 children in the United States (2). Compared to typically developing (TD) children or children with other disabilities (3, 4), children with ASD are more likely to exhibit comorbid high levels of internalizing (e.g., depression or anxiety symptoms) and externalizing (e.g., hyperactivity, conduct problems, and attentional control) problems. Literature showed that the incidences of behavioral/conduct problems, anxiety, and depression in children with ASD are 60.8, 39.5, and 15.7%, respectively (3). Given that high rates of comorbid internalizing and externalizing problems in early childhood have a long-term impact on individuals, families, and society (5), the factors that may influence these problems in children with ASD need to be fully understood.

Parenting style is defined as a collection of parents’ attitudes, behaviors, and emotions (6). The two-factor theory (7, 8) suggests a reciprocal relationship in which parenting behaviors actively shape child behaviors as well as the other way around. For example, one study suggested that positive parenting styles reduced the risk of emotional and behavioral problems in TD children (9). By contrast, Pinquart et al. (10) found that permissive and neglectful parenting styles were more closely related to higher levels of externalizing problems. In children with ASD, previous studies also showed that less affection, more overprotection, and authoritarian control from the parents were significantly correlated to more severe behavioral problems (11, 12). These studies indicated that parenting style may be an important factor in the behavioral problems of children. However, the relations between parenting style and child’s behavioral problems have been mixed. In contrast, previous studies have shown non-directional (13) or bidirectional (14) relations between parenting style and behavioral problems in TD children. One of the theoretical mechanisms underlying the association between parenting style and behavior problems in children is the coercion theory (15). The central idea is that a low level of support and neglectful parenting styles as risk factors for children’s behavioral problems, and negative reinforcement will lead to the persistence of bad behavior of children and parents (10). Unfortunately, whether or not the different dimensions of parenting style lead to different behavioral problems in children with ASD and TD remains unclear. Thus, determining the direction of parenting styles as it relates to a child’s behavioral problems may help guide parents in their approach to parenting a child with ASD.

Literature showed that parental characteristics may be related to parenting styles (16). Autistic traits fall below the threshold of clinical significance in ASD characteristics that are similar to but are not as severe as those with a clinical diagnosis of ASD (17, 18). There are several dimensions of autistic traits, such as the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ), which includes social skills, attention shift, attention to detail, communication, and imagination (19). Many studies showed that compared to parents of TD children, the parents of children with ASD had significantly higher levels of autistic traits than controls (20–22). Currently, several studies indicated that parental autistic traits were not only correlated with autism severity (23, 24) and children’s self-regulation (25) but also with childhood social–emotional behavior in children (26). A review suggested that parental autistic traits may be important in parsing heterogeneity in ASD etiology (27) and in developing parent-mediated ASD interventions (28). However, few studies have been conducted to investigate the association between the domains of parental autistic traits and behavioral problems in children with ASD.

In addition, some studies have tried to explore the relationships between parental autistic traits and negative aspects of parenting. For example, a few studies showed that higher parental autistic traits are associated with more parenting difficulties (29), lowest parenting efficacy (30), and poorer mental health (31). Some study suggested that poor attention switching (domain of autistic traits) was associated with parenting difficulties (32), and the communication of maternal autism traits in children with ASD was positively correlated with problem-solving of family function (15, 33).

Therefore, we hypothesize that some domains of autistic traits may be related to the parenting style and child behaviors and, thus, potentially moderate the relationship between the two in children with ASD. As noted, the previous study suggested differences in maternal and paternal parenting styles (34). Mothers spend more time with their children and have more caregiving and managerial roles compared to fathers (35–37). Thus, our study focused on the influence of maternal rearing patterns and autistic traits on behavioral problems in children. The current study may help adjust maternal parenting styles according to autistic traits and may provide a basis for early family intervention of ASD children.

In summary, the study aims to first, examine the differences in the behavioral problems of children with ASD and those with TD; second, evaluate the differences in maternal parenting styles between ASD and TD groups and determine whether a relationship exists between parenting styles and behavioral problems in the children; and finally, determine whether maternal autistic traits moderate the association between parenting styles and behavioral problems in the children.

Method

Participants and procedures

In this cross-sectional study, 70 children with ASD (Mage = 3.52, SD = 0.98), 98 TD children (Mage = 3.07, SD = 0.92), and all their mothers were recruited in Foshan, China, between May 2021 and September 2022. The inclusion criteria of the ASD group were diagnosed as ASD by two chief psychiatrists (SJH and HY) using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria, and the total score in the Children Autism Rating Scale (CARS) of all children with ASD was a score above 36. A group of TD children without ASD diagnosis was also recruited from the same child healthcare clinic. Those who had a history of developmental delay were excluded from the TD group. Additional inclusion criteria for selecting both groups were chronological age (between 2 and 5 years old) and all the children accompanied by mothers. Known genetic or chromosomal abnormalities (such as down syndrome and fragile X syndrome), significant organic diseases (such as blindness and deafness), and comorbidity with other mental disorders (such as childhood schizophrenia and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder) based on the self-report by mothers were excluded for selecting both groups.

First, the selecting ASD group was recruited after the diagnosis by the doctor and the CARS score was greater than 36. Then, all the children accompanied by their mothers were invited to participate in this study. All mothers provided informed consent before they were individually interviewed by health personnel who received standardized training in conducting face-to-face interviews. Mothers of the two groups were asked to answer many structured questionnaires on behavioral problems in the children as well as in maternal parenting styles and autism-like traits, among others. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health at Sun Yat-sen University.

Demographic information

Using self-made questionnaires, we collected the demographic information of the subjects, including maternal age, maternal education, income, child age, and child gender.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire ((SDQ)-parent form) (38) was adapted by Kou and Du from Goodman et al.’s study (39). The SDQ is a 25-item that uses a 3-point Likert scale (“not true,” “somewhat true,” or “certainly true”) and is designed to assess behavioral and emotional problems in children and adolescents ages 3–17 (38). Previous studies also show that the scale is applicable to 2-year-old children in China (40). Thus, mothers were asked to complete the extended parent version of the SDQ for ASD children. The items are divided into five subscales: hyperactivity/inattention, emotional symptoms, peer problems, conduct problems, and prosocial behavior. The composite scores for internalizing problems (emotional and peer items) and externalizing problems (conduct and hyperactivity items) were then analyzed in the current study (41). The SDQ has good reliability and structural validity in Chinese individuals (38).

Parental Behavior Inventory (PBI)

The PBI is a 20-item, parent-report questionnaire that uses a 6-point Likert scale (never to always) (42). The questionnaire yields two subscales: support/participation and hostility/coercion parenting styles. It is used to assess the parenting style among preschool and school-age children. Mothers were asked to complete the questionnaire. PBI has good reliability and structural validity in Chinese populations, with Cronbach’s α values of 0.807 and 0.652 for support/participation and hostility/coercion, respectively, for Chinese individuals (43).

Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) in adults

Maternal autistic traits were evaluated using the AQ (19). The AQ comprises 50 questions and uses a 4-point Likert scale (absolutely agree to absolutely disagree), with 10 questions assessing five different domains: social skills, attention switching, attention to detail, communication skills, and imagination. Each of these items scores 1 point if the respondent records the autistic-like trait either mildly or strongly. The maximum value for each subscale is 10 points. A higher score indicates more severe autistic traits. The AQ has good reliability and structural validity in Chinese adults (44).

Children Autism Rating Scale (CARS)

This scale is used by trained professionals to assess the interpersonal relationship, imitation, emotional response, language communication, and other aspects of autistic children over a period of 18 months. The scale is composed of 15 items that use a 4-point Likert scale (age-related performance, mild abnormality, moderate abnormality, and severe abnormality). The higher the total score on the scale, the more serious the symptoms; a total score of between 30 and 36 indicates mild–moderate autism, and a score above 36 indicates severe autism (45). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.73 in the Chinese version (46). In the current study, autistic children with a score above 36 were included.

Gesell Development Schedules (GDS)

The GDS is currently a widely used neurodevelopmental scale that consists of five domains, namely adaptability, gross motor, fine motor, language, and personal-social (47). The developmental quotient (DQ) of the five domains is used to evaluate the level of neurodevelopment. The higher the DQ, the better the neurodevelopment. The GDS has good reliability and validity in Chinese children (48). In the current study, a GDS score greater than 85 in all children is considered normal.

Statistical analysis

SPSS v23.0 statistical software was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables are presented as the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD), and count data are described by prevalence (%). Differences in demographic information and behavioral outcomes between the ASD and TD groups were compared by the t-test or chi-square test, with a significance level of p < 0.05. Hierarchical moderated regression analyses were used to determine whether or not maternal autistic traits moderate the association between maternal parenting styles and behavioral problems in the children. In the first step of the regression models, the independent variables were maternal parenting style (supportive/engaged vs. hostile/coercive) and maternal AQ domains separately across groups, controlling for child age, gender, DQ, family income, family income meeting demand, and maternal education level. The second step of the regression models included interaction terms between different parenting styles and each AQ domain. All five interaction terms were included in each regression model. For all moderated regression analyses, standardized variables (Z-scores) were used to compute the product terms. Simple slope analysis was conducted using the Process 2.16 macro plug-in of SPSS 23.0. Standardized regression coefficients were presented on all betas, and the significance level was p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic information analysis

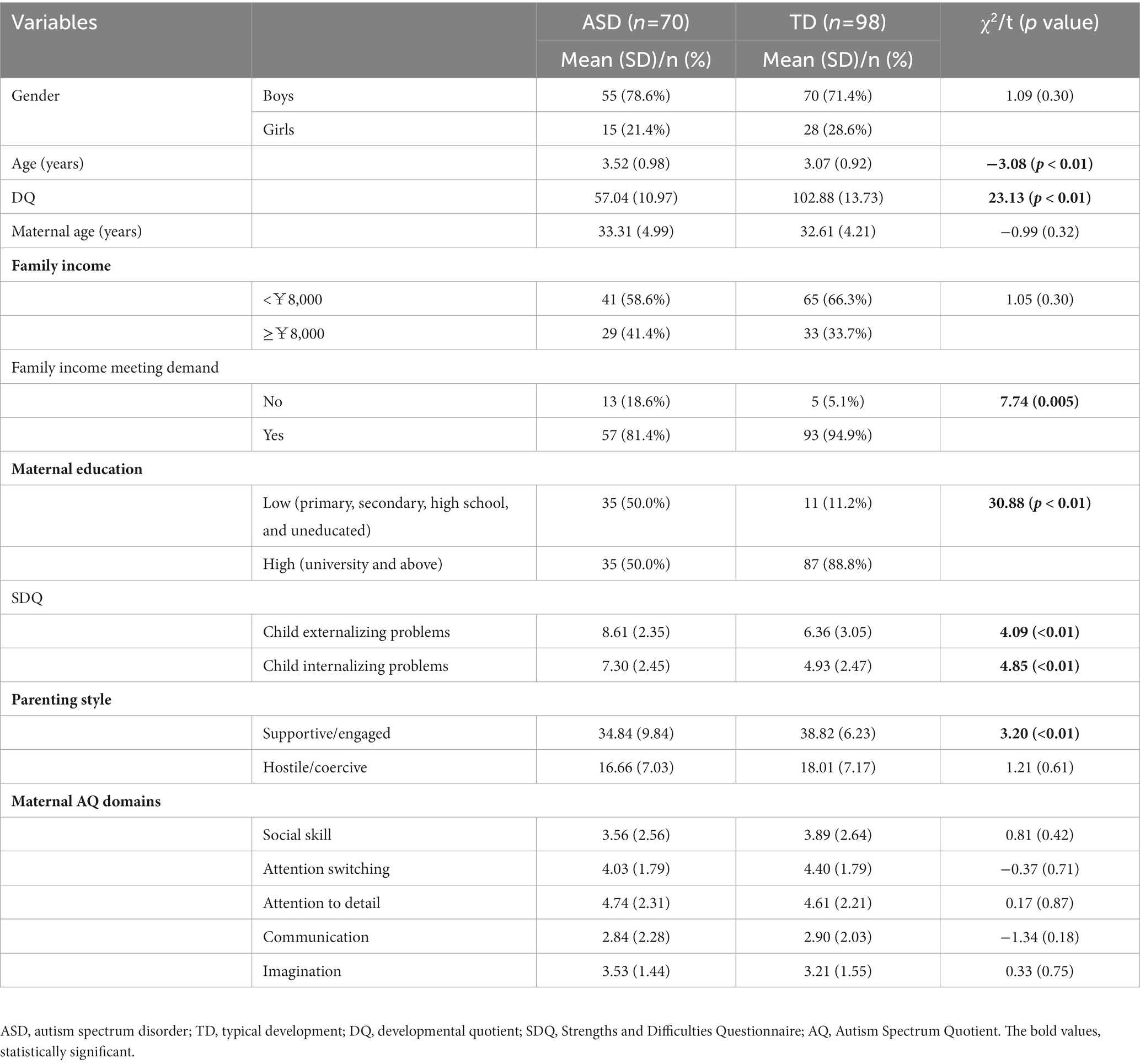

Compared to the TD group, the ASD group was significantly older (t = −3.08, p < 0.01) and had significantly lower DQ (t = 23.13, p < 0.01) and maternal education levels (χ2 = 30.88, p < 0.01). No significant differences were found in the maternal age, child gender, or family income (ps > 0.05) of the two groups. The results are shown in Table 1.

Comparison of children’s behavioral problems, parenting style, and maternal autistic traits of the two groups

The children with ASD exhibited significantly more externalizing problems (t = 4.09, p < 0.01) and internalizing problems (t = 4.85, p < 0.01) than the TD children. Moreover, compared to the mothers of the TD children, those of children with ASD scored lower in supportive/engaged parenting style (t = 3.20, p < 0.01). However, no significant differences were found in the maternal AQ domains of the ASD and TD groups (ps > 0.05). The results are shown in Table 1.

Association between maternal parenting style and autistic traits and child behavioral problems

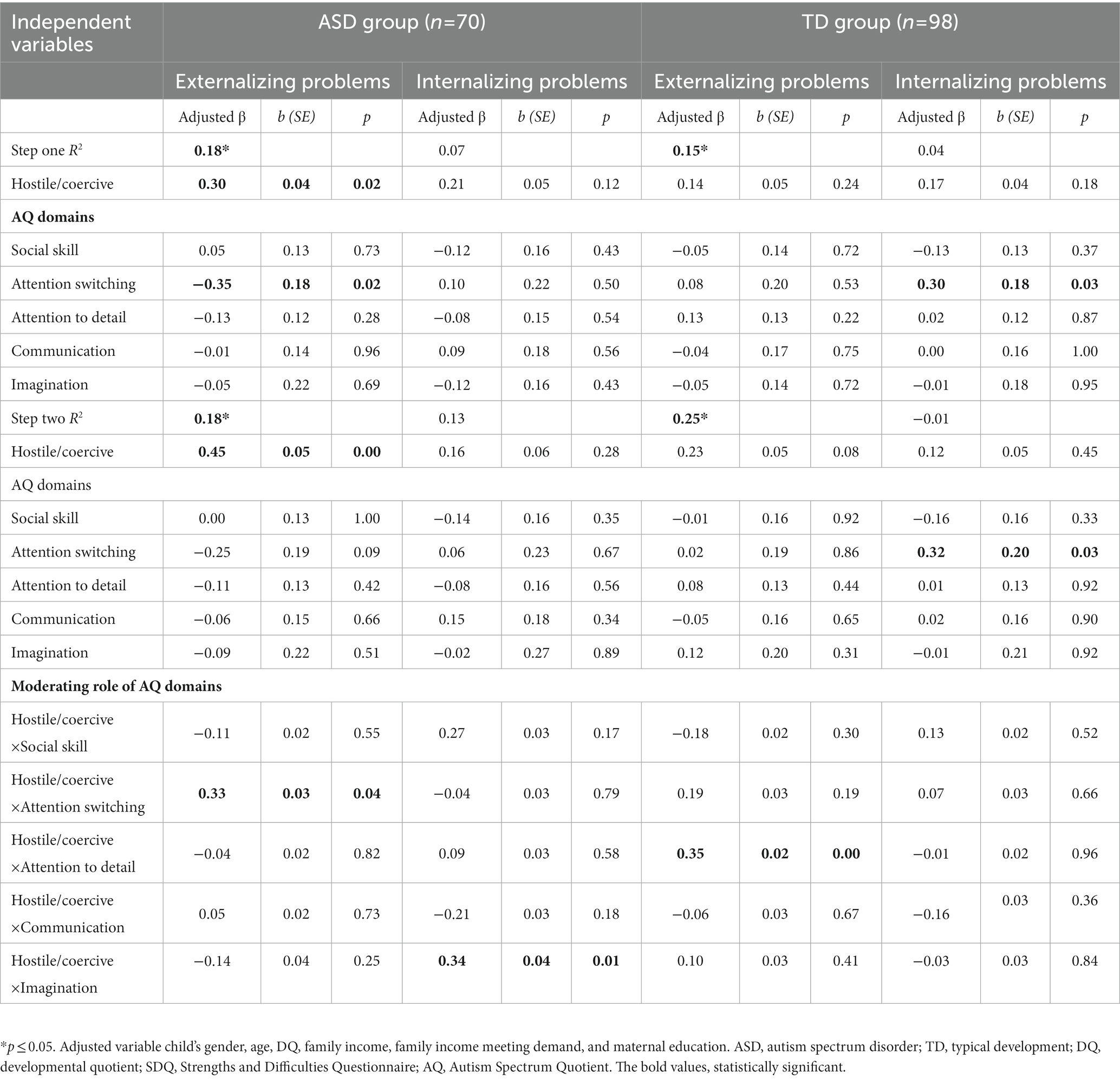

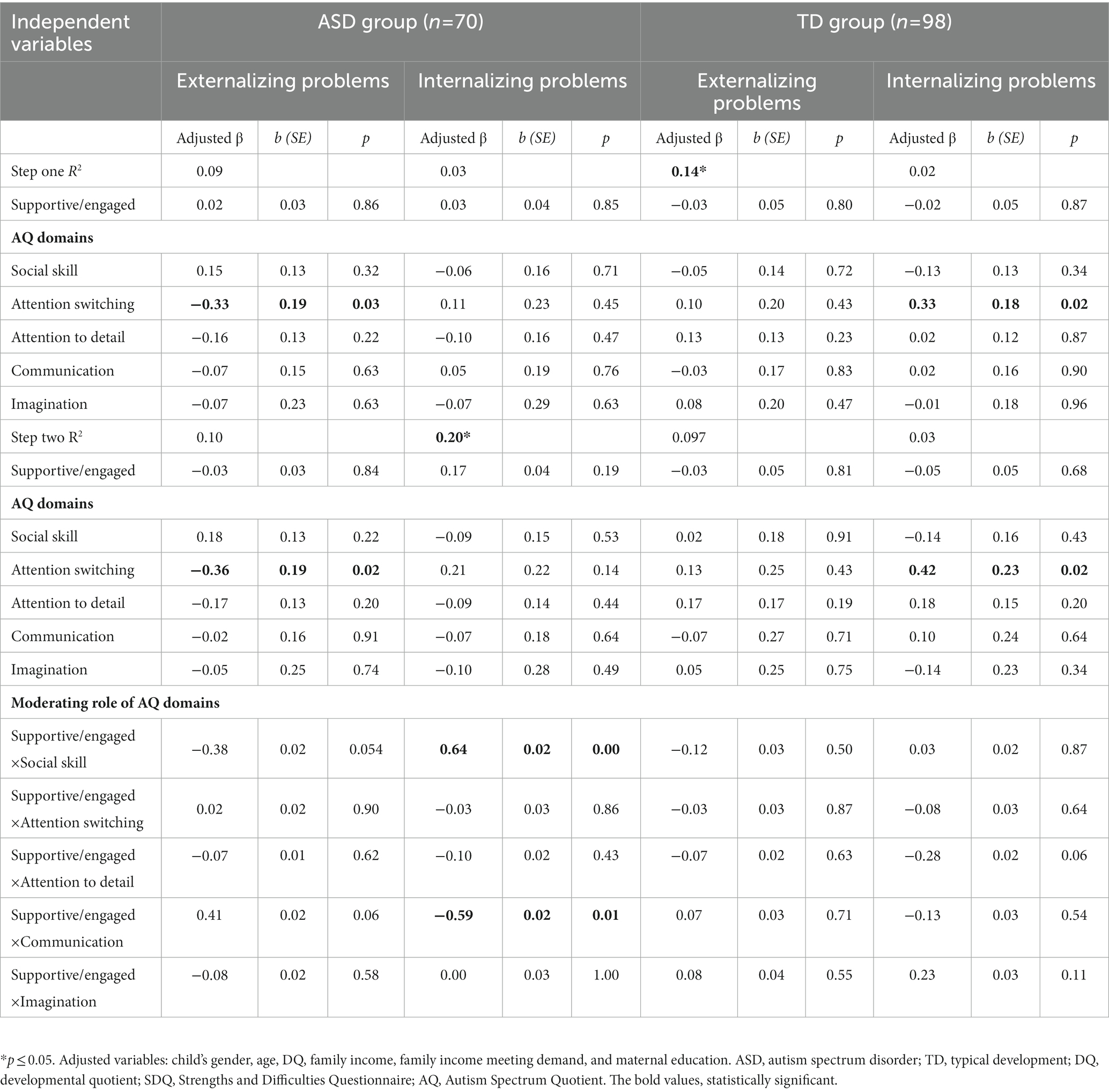

Multiple regression analysis showed that hostile/coercive parenting style significantly increased externalizing problems (β = 0.30, p = 0.02) only in the children in the ASD group after controlling for child age, gender, DQ, family income, family income meeting demand, maternal age, and maternal education level. In addition, the attention switching domain of maternal AQ was negatively correlated with externalizing problems (β = −0.35, p = 0.02) in ASD children. In the TD group, the maternal AQ attention switching domain was negatively associated with internalizing problems in the children (β = −0.30, p = 0.03). The results are shown in Tables 2, 3.

Table 2. Moderated multiple regression model of the hostile/coercive parenting behavior on behavior problems in children with ASD and TD.

Table 3. Moderated multiple regression model of the supportive/engaged parenting behavior on behavior problems in children with ASD and TD.

Moderation of maternal autistic traits on the relationship between maternal parenting style and children’s behavioral problems

In the moderation model, the main effect of maternal hostile/coercive parenting style on externalizing problems in the children remained significant (β = 0.45, p < 0.01). Moreover, this association was moderated by maternal attention switching (β = 0.33, p = 0.04) in the ASD group. In the model, we controlled for child age, gender, DQ, family income, family income meeting demand, maternal age, and maternal education level. The results are shown in Tables 2, 3.

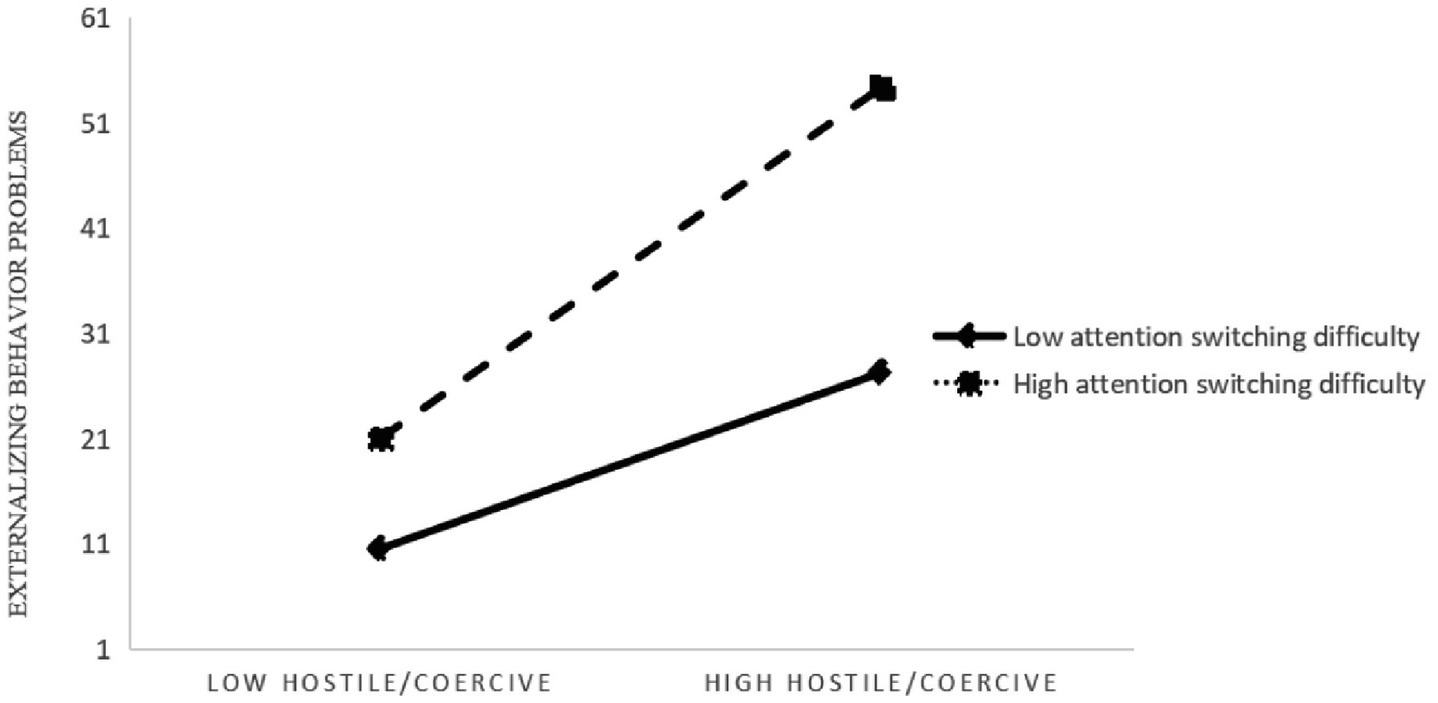

More importantly, the significant interaction between hostile/coercive parenting style and maternal AQ attention switching domain for child externalizing problems was probed and plotted at one standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderator (AQ attention switching severity; see Figure 1). Simple slope tests demonstrated that the association between maternal hostile/coercive parenting style and externalizing problems in the children with ASD was significant at high levels of maternal attention switching problems, such that greater use of hostile/coercive parenting style was associated with more externalizing problems in the children (b = 0.22, t = 3.43, p < 0.01). Similar results were found at medium levels of maternal attention switching problems (b = 0.14, t = 3.64, p < 0.01). By contrast, at low levels of attention switching problems, the correlation between maternal hostile/coercive parenting style and externalizing problems was non-significant (b = 0.06, t = 1.46, p = 0.15; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Maternal attention switching moderating the association between hostile/coercive parenting style and externalizing problems in children with ASD. At high levels of maternal attention switching problems, such that a greater use of hostile/coercive parenting style was associated with more externalizing problems in the children (p < 0.01). By contrast, at low levels of attention switching problems, the correlation between maternal hostile/coercive parenting style and externalizing problems was non-significant (p = 0.15). ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

Discussion

The findings of this study are as follows: (1) The children with ASD had more severe externalizing and internalizing problems than the TD children, and the maternal supportive/engaged parenting style scores in the ASD group were lower than those in the TD group; (2) maternal hostile/coercive parenting style was positively associated with child externalizing problems, and maternal AQ attention switching domain was negatively correlated with child externalizing problems in the ASD group; and (3) maternal AQ attention switching domain moderated the association between hostile/coercive parenting style and externalizing problems in children with ASD.

Association between maternal parenting style and behavioral problems in children with ASD

The current study showed that children with ASD exhibited more serious externalizing and internalizing problems than TD children. Consistent with our results, the literature showed that children with ASD had more severe internalizing problems such as anxiety/depressive symptoms than their TD peers (49–51). Moreover, ASD children displayed more externalizing problems such as peer conflict (49) and attention-deficit and hyperactivity symptoms (52, 53). We also found that the ASD group scored lower in maternal supportive/engaged parenting style than the TD group. Consistent with our findings, the literature indicated that children with ASD received less maternal affection and warmth than TD children (11, 54). It is possible that children with ASD lack reciprocal relationships, have communication impairments, and decreased response to social stimulation, which may result in a decrease in parents’ affectionate interactions with these children (55, 56). Of course, some studies showed that no significant differences were found in the maternal parenting styles in the ASD and TD groups (57, 58). This inconsistency may be the sample size, sample type, or limitation of the self-report instrument. Further studies are needed to determine the reasons for differing results.

Notably, the current study showed that maternal hostile/coercive parenting style was associated with externalizing behaviors in children with ASD. Similar to our results, previous studies suggested that children with ASD aged 6–10 years exhibited more externalizing behaviors under conditions of higher levels of parental critical comments and harsh-discipline parenting style (59), and higher levels of maternal discipline and harsh punishment parenting style were related to greater externalizing problems in ASD (12, 60). According to the coercion theory (15), we speculate that raising a child with ASD is quite stressful for parents because of the child’s social communication difficulties, narrow interests or stereotyped behaviors, and internalizing and externalizing behaviors, which can lead to hostile/coercive parenting styles. In turn, such a negative parenting style can increase the frequency and intensity of sadness, anger, and bad behaviors further in children with ASD (15). Thus, the relationship between hostile/coercive parenting and externalizing behavior highlights the importance of interventions that may break this negative cycle. By contrast, maternal hostile/coercive parenting style was not related to externalizing behaviors in TD children. The reason is not clear, and we suspect that it may be due to autistic traits in children with ASD such as persistent difficulties in social communication and interaction (1) and deficits in emotional functioning (49).

Moderation of maternal autistic traits in the relationship between maternal parenting style and externalizing behavioral problems in children with ASD

Attention switching is defined as diverting attention between tasks, which is considered a core cognitive ability that underlies the executive control of thought and action (61). Attention switching problems are expressed that people frequently get so strongly absorbed in one thing that loses sight of other things (19). Our multilevel analyses indicated that maternal attention switching was negatively associated with externalizing problems in the ASD group. We speculated that maternal autistic traits may affect children’s behavior either as a genetic predisposition (62) or together with other factors such as parenting style.

In the current study, we found that more likely hostile/coercive parenting styles were associated with more children’s externalizing problems at medium and high levels of maternal attention switching problems. Neuropsychological testing shows that parents of children with ASD have impaired executive function skills in the area of attentional flexibility (63). Moreover, previous evidence suggested that parents of children with ASD were found to have a “generativity deficit” in patterns meaning tasks (64). As mentioned previously, mothers may have a more negative parenting style (32) and potentially further impact parent–child interactions (65) in the context of high attention switching difficulty. Similarly, mothers with attention conversion difficulties may affect the development of children’s emotional and behavioral regulation abilities (25). One of the possible explanations for the moderate effect of attention switching difficulty on the association between hostile/coercive parenting style and children’s externalizing problems is that children’s needs and behaviors will change with different situations (66); however, the mother with poor attention switching will lack flexibility in parenting style, resulting in more hostility or coercion (32, 67). Based on the coercion theory (15), a more hostile/coercive parenting style may affect the interaction with the child and impact the child’s social–emotional engagement, communication, and social interaction abilities (68, 69), which then leads to poorer child developmental outcomes. Thus, maternal parenting style and autistic traits should be assessed early and should be included in early family-level interventions to help mothers to develop strategies for interaction with ASD children.

Several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, our study design was cross-sectional and thus could not prove the causal relationship between maternal parenting style and autistic traits with behavioral problems in the children. Second, this study only included female caregivers. Further research is needed to clarify the influence of both maternal and paternal characteristics on children’s developing behavioral problems. Third, all indicators in the study were assessed by a questionnaire. In future, cognitive assessments can be used to improve the objectivity of the results. Fourth, only children with severe autism were selected for the current study, and future studies will be considered the effect of the severity of autism on parenting style. Finally, the sample size is small; thus, future studies should consider these questions in a larger sample.

Conclusion

Children with ASD exhibited more severe externalizing and internalizing problems than TD children. Moreover, the ASD group scored lower in maternal supportive/engaged parenting style scores than the TD group. Among mothers with greater use of hostile/coercive, their autistic children were more likely to present externalizing problems. In particular, the maternal AQ attention switching domain moderated the association between hostile/coercive parenting styles and externalizing problems in children with ASD. The current study suggests mothers of children with ASD reduce hostile/coercive parenting styles and improve their maternal attention switching may reduce externalizing problems.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health at Sun Yat-sen University. The code is 20210124. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

XjL designed the study. XS, SH, HY, and XjL performed the survey research. LL, MC, and ZL analyzed the data. XjL drafted the manuscript. XW, XhL, and JJ were the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the Key R&D Program of Guangdong Province (grant number 2019B030335001), the Social-Area Science and Technology Research Program of Foshan City (Department of Science and Technology of Foshan City, 2120001008276), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81872639).

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of the participating children and their parents throughout this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Roehr, B. American psychiatric association explains DSM-5. Bmj. (2013) 346:f3591. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3591

2. Maenner, MJ, Shaw, KA, Bakian, AV, Bilder, DA, Durkin, MS, Esler, A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2021) 70(11:1–16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1

3. Kerns, CM, Rast, JE, and Shattuck, PT. Prevalence and correlates of caregiver-reported mental health conditions in youth with autism spectrum disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. (2020) 82:20m13242. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13242

4. Craig, F, De Giacomo, A, Operto, FF, Margari, M, Trabacca, A, and Margari, L. Association between feeding/mealtime behavior problems and internalizing/externalizing problems in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), other neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) and typically developing children. Minerva Pediatr. (2019) 12:35–40. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4946.19.05371-4

5. Baird, G, Simonoff, E, Pickles, A, Chandler, S, Loucas, T, Meldrum, D, et al. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: The special needs and autism project (SNAP). Lancet. (2006) 368:210–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7

6. Darling, N, and Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context. Psychol Bull. (1993) 113:487–96. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

7. Burke, JD, Pardini, DA, and Loeber, R. Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2008) 36:679–92. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9219-7

8. Maccoby, EE. The role of parents in the socialization of children: An historical overview. Dev Psychol. (1992) 28:1006–17. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.6.1006

9. Shaffer, A, Lindhiem, O, and Kolko, D. Treatment effects of a primary care intervention on parenting behaviors: Sometimes it’s relative. Prev Sci. (2017) 18:305–11. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0689-5

10. Pinquart, M. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Dev Psychol. (2017) 53:873–932. doi: 10.1037/dev0000295

11. Gau, SS, Chou, MC, Lee, JC, Wong, CC, Chou, WJ, Chen, MF, et al. Behavioral problems and parenting style among Taiwanese children with autism and their siblings. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2010) 64:70–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.02034.x

12. Maljaars, J, Boonen, H, Lambrechts, G, Van Leeuwen, K, and Noens, I. Maternal parenting behavior and child behavior problems in families of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. (2014) 44:501–12. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1894-8

13. Pan, W, Gao, B, Long, Y, Teng, Y, and Yue, T. Effect of Caregivers’ parenting styles on the emotional and behavioral problems of left-behind children: The parallel mediating role of self-control. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:12714. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312714

14. Wittig, SMO, and Rodriguez, CM. Emerging behavior problems: Bidirectional relations between maternal and paternal parenting styles with infant temperament. Dev Psychol. (2019) 55:1199–210. doi: 10.1037/dev0000707

15. Patterson, GR, Reid, J, and Dishion, T. A social learning approach: Vol. 4. Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia (1992).

16. Crowell, JA, Keluskar, J, and Gorecki, A. Parenting behavior and the development of children with autism spectrum disorder. Compr Psychiatry. (2019) 90:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.11.007

17. Bhattacharya, M, Chatterjee, S, Karmakar, A, and Dogra, AK. Autistic traits in Indian general population and patient group samples: Distribution, factor structure, reliability and validity of the autism-Spectrum quotient. J Adv Autism. (2022) 8:207–16. doi: 10.1108/AIA-08-2020-0049

18. Losh, M, and Piven, J. Social-cognition and the broad autism phenotype: Identifying genetically meaningful phenotypes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2007) 48:105–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01594.x

19. Baron-Cohen, S, Hoekstra, RA, Knickmeyer, R, and Wheelwright, S. The autism-Spectrum quotient (AQ)—adolescent version. J Autism Dev Disord. (2006) 36:343–50. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0073-6

20. Bora, E, Aydın, A, Saraç, T, Kadak, MT, and Köse, S. Heterogeneity of subclinical autistic traits among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Identifying the broader autism phenotype with a data-driven method. Autism Res. (2017) 10:321–6. doi: 10.1002/aur.1661

21. Hasegawa, C, Kikuchi, M, Yoshimura, Y, Hiraishi, H, Munesue, T, Nakatani, H, et al. Broader autism phenotype in mothers predicts social responsiveness in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2015) 69:136–44. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12210

22. Wheelwright, S, Auyeung, B, Allison, C, and Baron-Cohen, S. Defining the broader, medium and narrow autism phenotype among parents using the autism spectrum quotient (AQ). Mol Autism. (2010) 1:10. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-1-10

23. Mohammadi, M, and Zarafshan, H. Family function, parenting style and broader autism phenotype as predicting factors of psychological adjustment in typically developing siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders. Iran J Psychiatry. (2014) 9:55–63.

24. Sasson, NJ, Lam, KS, Parlier, M, Daniels, JL, and Piven, J. Autism and the broad autism phenotype: Familial patterns and intergenerational transmission. J Neurodev Disord. (2013) 5:11. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-5-11

25. DeLucia, EA, McKenna, MP, Andrzejewski, TM, Valentino, K, and McDonnell, CG. A pilot study of self-regulation and behavior problems in preschoolers with ASD: Parent broader autism phenotype traits relate to child emotion regulation and inhibitory control. J Autism Dev Disord. (2022) 52:4397–411. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05322-z

26. Loncarevic, A, Maybery, MT, and Whitehouse, AJO. The associations between autistic and communication traits in parents and developmental outcomes in children at familial risk of autism at 6 and 24 months of age. Infant Behav Dev. (2021) 63:101570. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2021.101570

27. Rubenstein, E, Wiggins, LD, Schieve, LA, Bradley, C, DiGuiseppi, C, Moody, E, et al. Associations between parental broader autism phenotype and child autism spectrum disorder phenotype in the study to explore early development. Autism. (2019) 23:436–48. doi: 10.1177/1362361317753563

28. Rubenstein, E, and Chawla, D. Broader autism phenotype in parents of children with autism: A systematic review of percentage estimates. J Child Fam Stud. (2018) 27:1705–20. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1026-3

29. Dissanayake, C, Richdale, A, Kolivas, N, and Pamment, L. An exploratory study of autism traits and parenting. J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 50:2593–606. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03984-4

30. Lau, W, Peterson, CC, Attwood, T, Garnett, MS, and Kelly, A. Parents on the autism continuum: Links with parenting efficacy. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2016) 26:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2016.02.007

31. Su, X, Cai, RY, and Uljarević, M. Predictors of mental health in Chinese parents of children with autism Spectrum disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. (2018) 48:1159–68. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3364-1

32. Saito, A, Matsumoto, S, Sato, M, Sakata, Y, and Haraguchi, H. Relationship between parental autistic traits and parenting difficulties in a Japanese community sample. Res Dev Disabil. (2022) 124:104210. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104210

33. Guo, K, Xiao, H, Jia, C, Mingjing, S, and Yin, H. Behavioral problems in children with autism and their correlation with autism traits and family functions of parents in China. Chin J Psychiatry. (2016) 3:148–53. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7884.2016.03.005

34. Bornstein, MH. Handbook of parenting. Volume 1: Children and parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers (2002).

35. Ozturk, Y, Riccadonna, S, and Venuti, P. Parenting dimensions in mothers and fathers of children with autism Spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2014) 8:1295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.07.001

36. Flippin, M, and Watson, LR. Fathers’ and Mothers’ verbal responsiveness and the language skills of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. (2015) 24:400–10. doi: 10.1044/2015_AJSLP-13-0138

37. Giannotti, M, Bonatti, SM, Tanaka, S, Kojima, H, and de Falco, S. Parenting stress and social style in mothers and fathers of children with autism spectrum disorder: A cross-cultural investigation in Italy and Japan. Brain Sci. (2021) 11:1419. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11111419

38. Kou, JH, Du, YS, and Xia, LM. Reliability and validity of “children strengths and difficulties questionnaire” in Shanghai norm. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. (2005) 17:25–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2005.01.007

39. Goodman, R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2001) 40:1337–45. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

40. Ying, H, Haifeng, Z, and Lian, T. Preliminary development and evaluation of responsive care evaluation scale for infants and young children in China. Chin J Child Health. (2022) 30:386–91. doi: 10.11852/zgetbjzz2021-0474

41. Goodman, A, Lamping, DL, and Ploubidis, GB. When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2010) 38:1179–91. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x

42. Lovejoy, M, Weis, R, O’Hare, E, and Rubin, EC. Development and initial validation of the parent behavior inventory. Psychol Assess. (1999) 11:534–45. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.11.4.534

43. Jia, SM, Wang, L, Tan, H, Wang, X, Shi, YJ, Ping, LI, et al. Application of the Chinese version of parent behavior inventory. Chin J Child Health Care. (2013) 21:916–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-6554.2011.06.029

44. Gouoyao, L. The trial of autism Spectrum quotient among Chinese college students. J Changchun Univ Technol. (2014) 131–134.

45. Schopler, E, Reichler, RJ, DeVellis, RF, et al. Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). J Autism Dev Disord. (1980) 10:91–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02408436

46. Lu, J, Yang, Z, Shu, M, et al. Reliability, validity analysis of the childhood autism rating scale. China J Modern Med. (2004) 14:119–121. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-8982.2004.13.037

47. Ball, RS. The Gesell developmental schedules: Arnold Gesell (1880-1961). J Abnorm Child Psychol. (1977) 5:233–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00913694

48. Wang, C, Wang, Q, Xiang, B, Chen, S, Xiong, F, and Ji, Y. Effects of propranolol on neurodevelopmental outcomes in patients with infantile hemangioma: A case-control study. Biomed Res Int. (2018) 2018:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2018/5821369

49. Li, B, Bos, MG, Stockmann, L, and Rieffe, C. Emotional functioning and the development of internalizing and externalizing problems in young boys with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism. (2020) 24:200–10. doi: 10.1177/1362361319874644

50. Lai, MC, Kassee, C, Besney, R, Bonato, S, Hull, L, Mandy, W, et al. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:819–29. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

51. Ferguson, BJ, Dovgan, K, Takahashi, N, and Beversdorf, DQ. The relationship among gastrointestinal symptoms, problem behaviors, and internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psych. (2019) 10:194. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00194

52. Hong, JS, Singh, V, and Kalb, L. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. (2021) 14:182–92. doi: 10.1002/aur.2414

53. Hwang-Gu, SL, Lin, HY, Chen, YC, Tseng, YH, Hsu, WY, Chou, MC, et al. Symptoms of ADHD affect intrasubject variability in youths with autism spectrum disorder: An ex-gaussian analysis. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2019) 48:455–68. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1452151

54. van Steijn, DJ, Oerlemans, AM, van Aken, MA, Buitelaar, JK, and Rommelse, NN. Match or mismatch? Influence of parental and offspring ASD and ADHD symptoms on the parent-child relationship. J Autism Dev Disord. (2013) 43:1935–45. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1746-y

55. Konstantareas, MM, and Homatidis, S. Mothers’ and fathers’ self-report of involvement with autistic, mentally delayed, and normal children. J Marriage Fam. (1992) 54:153–64. doi: 10.2307/353283

56. Rutgers, AH, van Ijzendoorn, MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg, MJ, Swinkels, SH, van Daalen, E, Dietz, C, et al. Autism, attachment and parenting: A comparison of children with autism spectrum disorder, mental retardation, language disorder, and non-clinical children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2007) 35:859–70. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9139-y

57. Ostfeld-Etzion, S, Feldman, R, Hirschler-Guttenberg, Y, Laor, N, and Golan, O. Self-regulated compliance in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder: The role of temperament and parental disciplinary style. Autism. (2016) 20:868–78. doi: 10.1177/1362361315615467

58. Feldman, R, Golan, O, Hirschler-Guttenberg, Y, Ostfeld-Etzion, S, and Zagoory-Sharon, O. Parent-child interaction and oxytocin production in pre-schoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Br J Psychiatry. (2014) 205:107–12. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.137513

59. Baker, JK, Fenning, RM, Erath, SA, Baucom, BR, Messinger, DS, Moffitt, J, et al. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, parenting, and externalizing behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. (2020) 24:109–20. doi: 10.1177/1362361319848525

60. Graziano, PA, Keane, SP, and Calkins, SD. Maternal behavior and Children’s early emotion regulation skills differentially predict development of Children’s reactive control and later effortful control. Infant Child Dev. (2010) 19:333–53. doi: 10.1002/icd.670

61. Wager, TD. Brain and behavioral mechanisms of switching attention. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan (2003).

62. Piven, J, Palmer, P, Jacobi, D, Childress, D, and Arndt, S. Broader autism phenotype: Evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families. Am J Psychiatry. (1997) 154:185–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.185

63. Hughes, C, Leboyer, M, and Bouvard, M. Executive function in parents of children with autism. Psychol Med. (1997) 27:209–20. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004308

64. Wong, D, Maybery, M, Bishop, DV, Maley, A, and Hallmayer, J. Profiles of executive function in parents and siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Genes Brain Behav. (2006) 5:561–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00199.x

65. Wan, MW, Green, J, and Scott, J. A systematic review of parent-infant interaction in infants at risk of autism. Autism. (2019) 23:811–20. doi: 10.1177/1362361318777484

66. Phillips, D, and Mccartney, K, Scarr SJDP. Child-care quality and children’s. Soc Dev. (1987) 23:537–43. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.23.4.537

67. Marriott, E, Stacey, J, Hewitt, OM, and Verkuijl, N. Parenting an autistic child: Experiences of parents with significant autistic traits. J Autism Dev Disord. (2021) 52:3182–93. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05182-7

68. Thomas, JC, Letourneau, N, Campbell, TS, Tomfohr-Madsen, L, and Giesbrecht, GF. Developmental origins of infant emotion regulation: Mediation by temperamental negativity and moderation by maternal sensitivity. Dev Psychol. (2017) 53:611–28. doi: 10.1037/dev0000279

Keywords: parenting style, autistic traits, behavioral problem, autism spectrum disorder, children

Citation: Lin X, Su X, Huang S, Liu Z, Yu H, Wang X, Lin L, Cao M, Li X and Jing J (2023) Association between maternal parenting styles and behavioral problems in children with ASD: Moderating effect of maternal autistic traits. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1107719. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1107719

Edited by:

Lu Liu, Peking University Sixth Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Wenhan Yang, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, ChinaOrawan Louthrenoo, Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Copyright © 2023 Lin, Su, Huang, Liu, Yu, Wang, Lin, Cao, Li and Jing. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiuhong Li, bGl4aEBtYWlsLnN5c3UuZWR1LmNu; Jin Jing, amluZ2ppbkBtYWlsLnN5c3UuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Xiujin Lin1

Xiujin Lin1 Xin Wang

Xin Wang Lizi Lin

Lizi Lin Muqing Cao

Muqing Cao Xiuhong Li

Xiuhong Li Jin Jing

Jin Jing