- 1Faculty of Medicine, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, Macao SAR, China

- 2Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3Faculty of Health, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Background: There has been an increasing awareness and recognition of mental well-being as one of the main outcome measures in national mental health policy and service provision in recent years. Many systemic reviews on intervention programmes for mental health or general well-being in young people have been conducted; however, these reviews were not mental well-being specific.

Objective: This study aims to examine the effectiveness of child and adolescent mental well-being intervention programmes and to identify the approach of effective intervention by reviewing the available Randomised Controlled Trials.

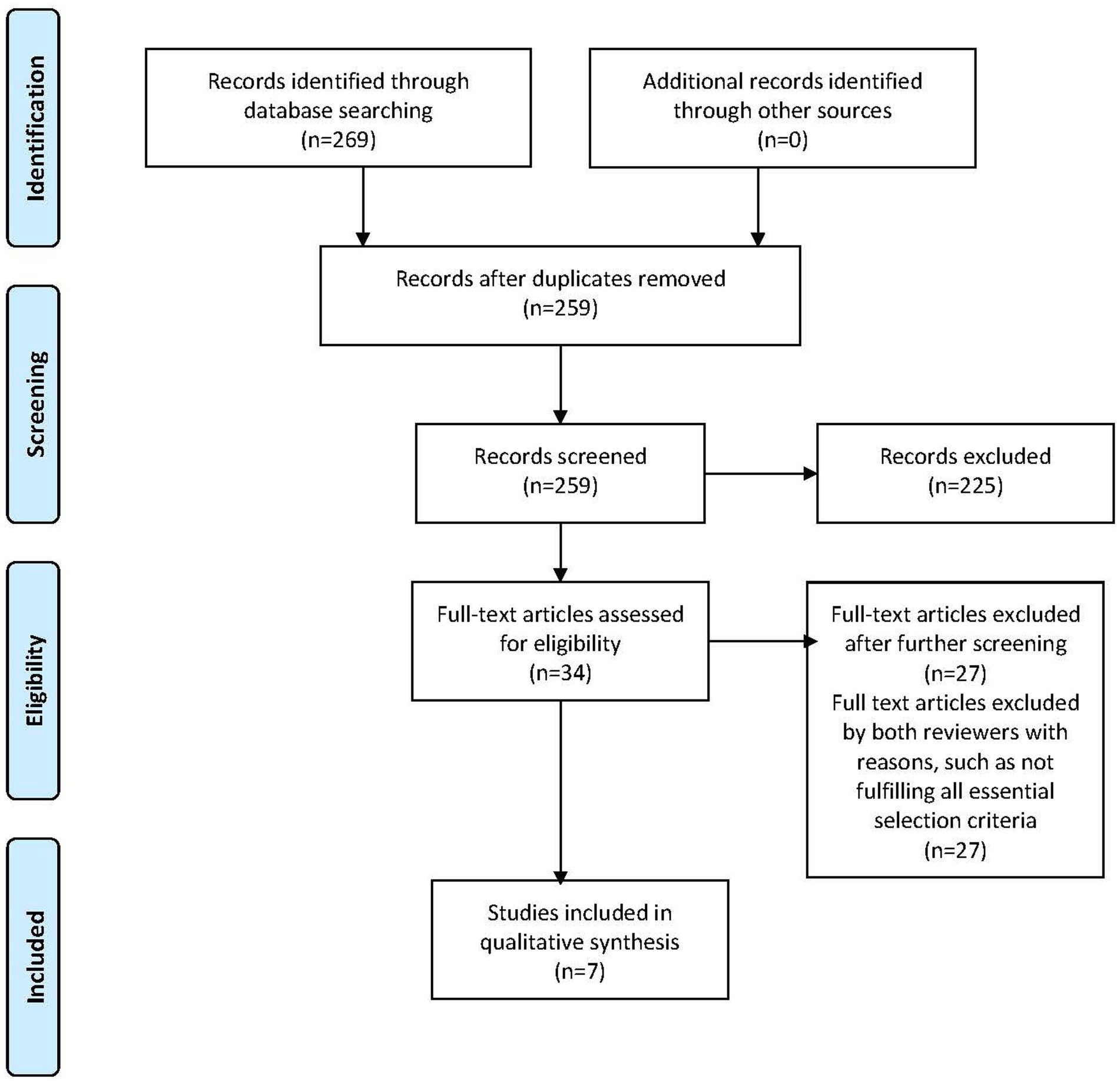

Methods: This systematic review study followed the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews ensuring a methodical and structured approach for the literature search and the subsequent review processes. The systematic literature search utilised major medical and health databases. Covidence, an online application for conducting systematic reviews, was used to assemble the titles, abstracts and full articles retrieved from the initial literature search. To examine the quality of the included trials for determining the strength of the evidence provided, the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Randomised Controlled Trial was used.

Results: There were 34 studies identified after an extensive search of the literature following the PRISMA guidelines. Seven (7) fulfilled all selection criteria and provided information on the effect of an intervention programme on mental well-being in adolescence. Data were extracted and analysed systematically with key information summarised. The results suggested that two (2) programmes demonstrated significant intervention effects, but with a small effect size. The quality of these trials was also assessed using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Randomised Controlled Trials and identified some methodological issues.

Conclusion: In conclusion, activity-based and psychoeducation are shown to be potentially effective approaches for future programme development. More research on a well-designed programme is urgently needed, particularly in developing countries, to provide good evidence in supporting the mental health policy through the enhancement of mental well-being in young people.

Introduction

Positive mental health, as a concept representing self-acceptance, personal growth and actualisation, resilience, self-autonomy and mastery of the environment, has long been proposed (1). Instead of focusing on mental illness, there is an increasing emphasis on positive mental health and its effects on population health by the World Health Organization (2). Mental well-being has also been gaining much attention in the past two decades (2). The WHO defined positive mental health or good mental health as a: ‘state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’ (3). This definition captures the concept that mental health is more than just an absence of mental illness (4). At the same time, there is also a growing acceptance that mental well-being, although closely resembles mental health, is a slightly different construct (5). Peterson has further defined mental well-being as: “the state of thriving in various areas of life, such as in relationships, at work, play, and more, despite ups and downs. It’s the knowledge that we are separate from our problems and the belief that we can handle those problems” (6). As the awareness and recognition of mental well-being have increased in recent years, it has become one of the main outcome measures in national mental health policy and service provision in many countries, particularly in the UK (7, 8).

In terms of the measurement of mental well-being, the concept encompasses multiple elements, so the construct is also complex (1). Assessment tools have been developed attempting to assess different aspects of mental well-being with some on the overall construct and others on specific domains. For example, the 5-item World Health Organization Well-being Index (WHO-5) was designed to assess the overall well-being of the mental state of an individual (9). The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) was another instrument developed for measuring three domains of well-being, namely emotional, psychological, and social (10). Based on the initial concept of mental well-being proposed by scholars in the field, such as Jahoda (1), Keyes (10), and Waterman (11), Tennant et al. proposed a two-dimensional model of mental well-being consisting of the hedonic and eudaimonic aspects (12, 13). The hedonic aspect refers to the individual subjective feeling of happiness and satisfaction in life, whereas the eudaimonic aspect is related to the psychological functioning and the actualisation of the individual’s potential, capacity, and positive relationship with self and others. Their efforts resulted in the development and validation of the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) (13). A recent systematic review of the instruments for measuring mental wellness in adolescents suggested a range of core elements reflected from many different tools (14). Given the multiplicity of core elements embedded in the construct of mental well-being, it would be prudent to confine the selection of measuring instruments to those that include both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects, or the majority of items included in the instrument should cover these aspects.

As noted, there is a close relationship between mental well-being and mental health. This has been demonstrated in many studies (15–18). For example, in the cohort study on the effects of physical activity on mental well-being and mental health among adolescents aged 12–13 in England, Bell and colleagues found that there was a negative association between mental well-being scores, assessed by the WEMWBS, and scores of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (r = −0.41) a measure of the mental health status (16). Another more recent study was conducted by Hides et al. on the relationship between mental well-being and psychological distress in a large sample of 2082 young people aged between 16 and 25 years in Australia. Results revealed that a bifactor model, in which mental well-being and distress were two separate constructs, was the only model that fitted well to the data with mental well-being and distress as subcomponents of mental health (18). While examining the relationship between changes in mental well-being and the inflammatory makers over time, Fancourt and Steptoe (17) discovered that elements of the two domains of mental well-being measures were negatively correlated to many inflammatory makers independent of the mental health status. These inflammatory markers had been identified to be associated with mental distress and ill health (17).

Mental Health problems among children and young adolescents have become a major public health issue. Global data indicated that the prevalence of mental health problems in children and adolescents was increasing a decade ago (19). Unfortunately, no improvement in the situation has been observed since then. On the contrary, the situation worsened in the past few years due to the COVID-19 pandemic (20). Early prevention of mental health problems is vital as mental health problems in almost half of adult patients start before the age of 14 (21). Good childhood mental health should be fostered during children’s early developmental processes. As mental well-being is an important aspect of good mental health, early intervention to promote mental well-being among children and adolescents is an important strategy for bettering mental health. If proven effective, this strategy will benefit not only young people but could potentially prevent mental ill health in the future adult population.

In terms of evidence-based practices, systematic reviews have been found on the intervention programmes for mental health or general well-being in young people; however, they were not mental well-being specific (22–26). While examining whether there are existing systematic reviews on the topic, main health-related databases were searched before the commencement of the current review study. The result is negative suggesting no previous review has been reported in the literature. In bridging the knowledge gap, this study aims, primarily, to examine the effect of child and adolescent mental well-being intervention programmes through a systematic review. It also attempts to identify the type of intervention programmes that have shown to be efficacious in bettering mental well-being in children and adolescents. To ensure the capturing of the best available evidence on the intervention programme, the review is limited to the reported Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) only.

Methods and materials

Search strategies

This systematic review study followed the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews ensuring a methodical and structured approach for the literature search and the subsequent review processes (27). The systematic literature search utilised major medical and health databases including (1) PubMed, (2) ScienceDirect, (3) CINAHL full text, (4) AMED, (5) and MEDLINE.

In terms of the keywords and syntax used for the search, the following were used: (‘mental well-being OR mental wellbeing’) AND (intervention program OR intervention) AND (Randomised Controlled Trials). A slightly modified syntax was used per the requirements of the database. The following inclusion criteria were applied to the search: (1) the article was published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) the article was written in the English language; (3) the study was an RCT of any type; (4) the outcome measure must fulfil the construct of mental well-being as defined above and (5) the target population of the RCT was children and adolescents. There was no restriction on the date of publication.

Covidence, an online application for conducting systematic reviews, was used to assemble the titles, abstracts, and full articles retrieved from the initial literature search. The steps below were undertaken to ensure all selection criteria of the review and the study selection for final data extraction, were satisfied. First, abstracts were screened for the required study type, and the trial was on an intervention programme for mental well-being in children and adolescents. Second, full texts of the selected articles from the previous step were examined to determine the suitability for data extraction. Both authors conducted the second step independently in accordance with the selection criteria. The results of the selection by the authors were then compared for similarities and to examine any discrepancies. Any differences in the selection were discussed and discrepancies were resolved by checking the selection criteria. Furthermore, to ensure that no other relevant studies might have been missed during the initial literature search, the reference lists of the selected articles for data extraction were also examined.

Selection criteria

While selecting studies for data extraction, the following criteria were observed: (1) The study was an RCT with mental well-being as one of the main outcome variables; (2) The mental well-being of the participants was assessed using a validated instrument with the essential domains of the construct included; (3) Results on the effects of the intervention programme were clearly presented allowing for an estimate of the efficacy of the intervention and (4) The study was published in the English language.

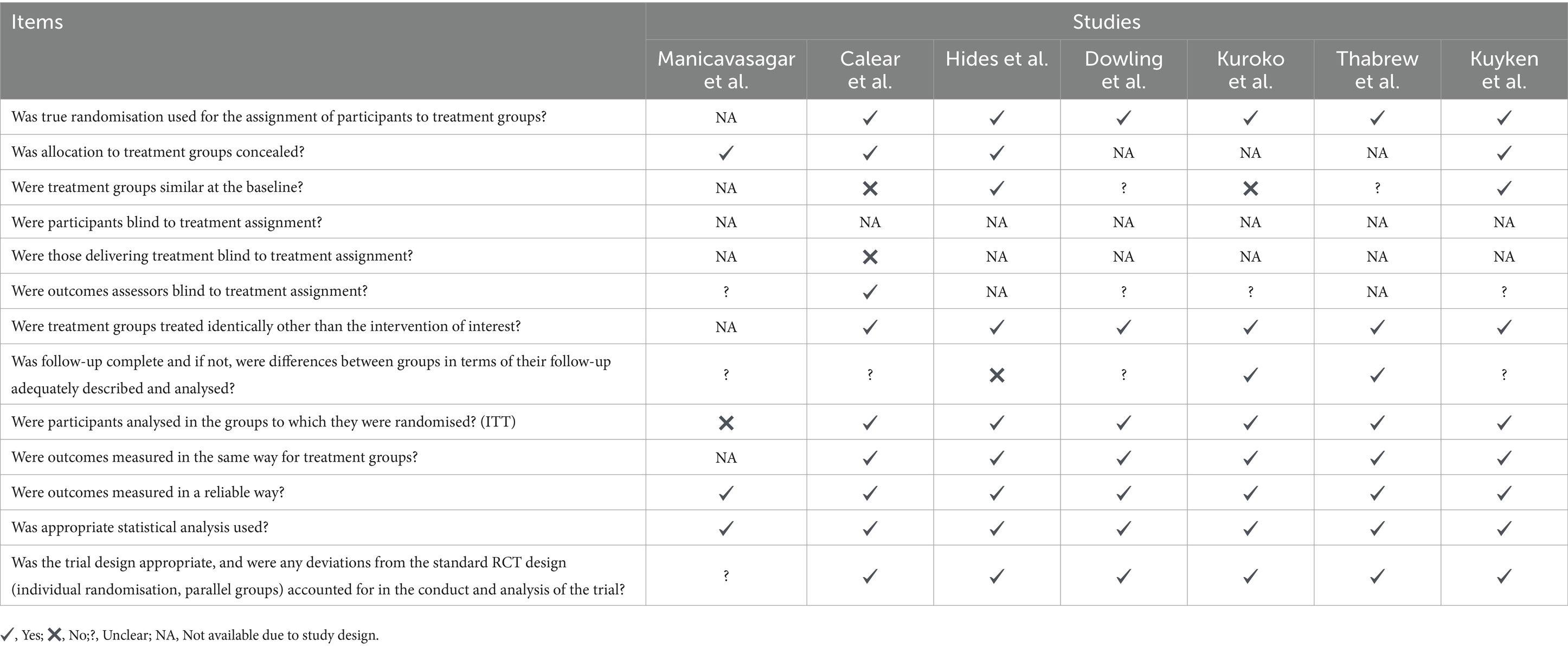

Information extraction, analysis, and publication quality assessment

For data extraction, information was captured from the included study and managed using the extraction tool provided in Covidence. This information included: authors, years of publication, location of the study, the study design, demographic characteristics of the sample, a description of the intervention programme, and the tools or instruments used to assess mental well-being. The results of the study, in terms of the effect of the intervention programme on mental well-being, were also recorded with an estimate of the effect size if available. The information was then summarised in a table for the analyses of a potential causal relationship between the intervention and the mental well-being of the participants. To examine the quality of the included trials for determining the strength of the evidence provided, the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Randomised Controlled Trial was used (28). The quality of each trial was rated against the JBI tool by both authors independently and then matched for similarities. Any discrepancies between the two were resolved by further reviewing the article for information. As the tool was not designed to be a psychometric scale, thus the assessment was conducted descriptively. Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA chart summarising the systematic literature searches and review process.

Results

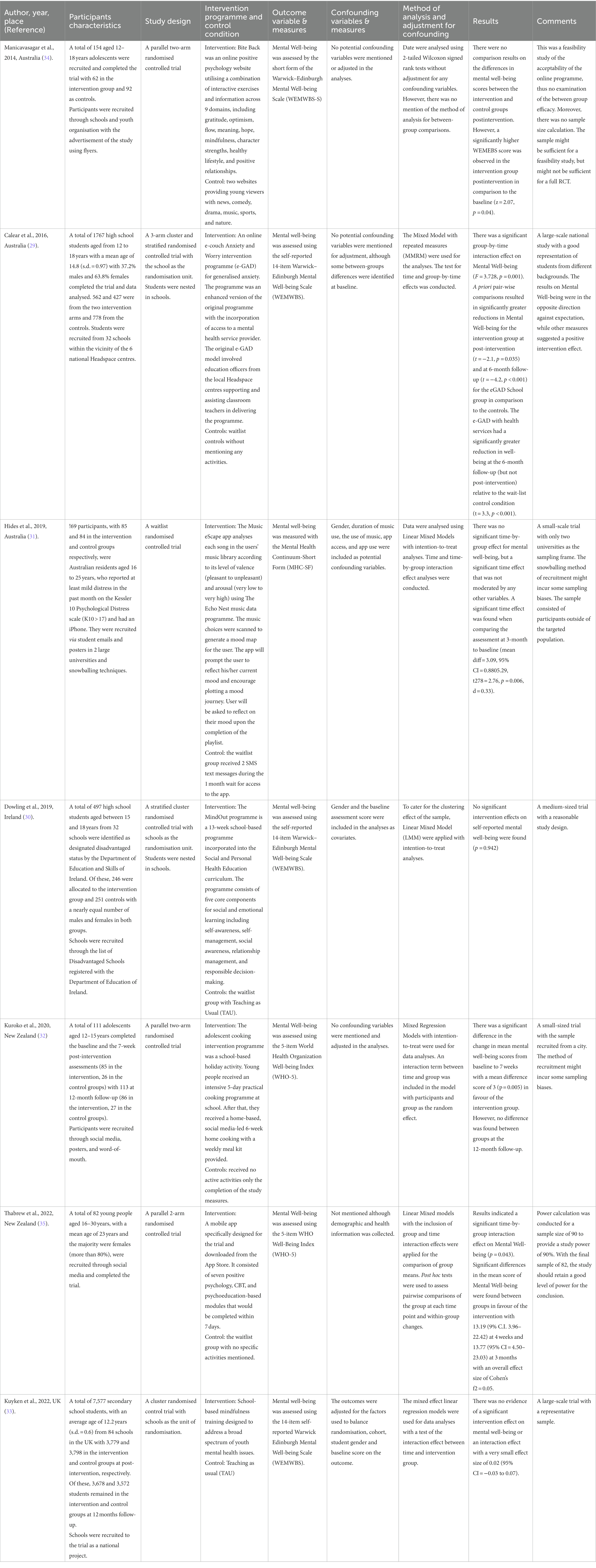

After following the literature search procedures on the five electronic databases, 34 articles were identified as potential studies for further screening. Of these 34 studies, only seven were found fulfilling all inclusion criteria (29–35). The main reasons for the exclusion of the 27 articles included: the outcome measure was not mental well-being as defined for this review study; the study design was not a proper RCT by the definition of a trial; the majority of the target population of the trial was not within the age range of children and adolescent. Data were extracted from the seven trials and information is summarised in Table 1. As shown, the sample size of these trials varied ranging from a small trial of 82 to the largest of 7,577 with a total of 10,357 participants aged younger than 19 years with two trials involving a small number of older young people (31, 35). In terms of the distribution of the sample size, two trials were large with more than a thousand participants, one medium size of about 500, and the rest were less than 200 (Table 1). The majority of these participants were recruited through schools or universities with some through social media and other communication means.

Table 1. Information extracted from the selected randomised controlled trials of intervention programmes for improving the mental well-being of children and adolescents.

For the study design, of the seven RCTs three were parallel arms trials on individual participants (32, 34, 35), three were cluster randomised controlled trials, with or without stratification (29, 30, 33), and one randomised wait-listed control trial (31). In terms of dates of the studies, most of these were recent studies with five being conducted within the past 5 years. All trials were implemented in developed countries with three in Australia (29, 31, 34)), two in New Zealand (32, 35), one in Ireland (30), and one in the UK (33). All studies utilised a standardised self-reported instrument for the assessment of mental well-being at the baseline and post-intervention. Four trials utilised the WEMWBS (29, 30, 33, 34), two used the WHO-5 (32, 35), and Hides et al. (31) employed the MHC-SF as the assessment tool.

In terms of intervention programmes, nearly half (n = 3, 43%) were using a psychoeducation approach, either school-based, online or App-based (30, 34, 35). Two were trials on e-couching methods of positive psychological training with one utilising additional face-to-face services and the other using an App-based musical mood training programme (13, 29). One study applied an individualised activity-based approach of a cooking programme (32), and one was a school-based mindfulness programme (33).

The efficacy of these intervention programmes was also analysed. Of the seven trials, only two demonstrated a significant effect of the intervention programme with both being conducted in New Zealand. Kuroko’s cooking intervention programme resulted in a significant difference in the change in mean mental well-being scores from baseline to 7 weeks with a mean difference score of 3 (p = 0.005) in favour of the intervention group (32). The psychoeducation programme conducted by Thabrew et al. (35) also found significant differences in the mean score of mental well-being between groups in favour of the intervention with 13.19 (9% CI 3.96–22.42) at 4 weeks and 13.77 (95% CI = 4.50–23.3) at 3 months with an overall small effect size of Cohen’s f2 = 0.05. The other trials found no significant intervention effects. One did not conduct comparisons between groups.

The quality of these studies was also assessed with the application of the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Randomised Controlled Trials. The results of the assessment are summarised in Table 2. As noted, most of these trials were of acceptable quality with many of the items scoring positive. However, owing to the study design of these trials with the use of online programme delivery and data collection, some of the items were unavailable for assessment. Particularly, items related to the blinding of treatment assignment to the participants, to the treatment deliverers, and to the assessors of outcomes. Another item of concern was related to the treatment applied to different arms of the trial at baseline. Most of the reports did not provide sufficient information for the assessment of this item. Furthermore, the follow-up of participants, either for post-intervention assessment or for longer-term assessments, was unclear in many of the trials. More detailed analyses of these reports showed that of these seven trials more than half (n = 4, 57%) were small-sized and might not be able to provide sufficient power for the study (Table 1). Moreover, one trial did not conduct a comparison of the outcome between groups (34). On the whole, the quality of these trials improved over time.

Discussions and conclusion

There are two aims of this study. First, to examine the possible effects of different intervention programmes on the mental well-being of children and adolescents through a systematic review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Second, to identify the type of intervention programmes, particularly the main contents that are shown to be efficacious for improving the mental well-being of young people. The results of the review suggest that not many well-designed RCTs were conducted in the past. The more recent studies carried out in the last 5 years were of better quality. Among the seven reviewed trials, only two demonstrated a significant effect of the implemented intervention on the mental well-being of participants. However, these two New Zealand trials were both of smaller size with one having 111 and the other 82. In terms of the effect of the intervention, while one study reported small effect size, the information provided in the articles was not sufficient to conduct a proper calculation on the treatment effect in comparison to the smallest worthwhile effect (36). In terms of the contents of the intervention programmes, one was activity-based, and the other was education-based programmes. Given the lack of a systematic review of a similar topic, this study would be considered unique and the first in the area.

The results obtained from this review provided some insights into the current development of intervention programmes for the advancement of mental good health via the improvement of mental well-being, particularly among children and young adolescents. As aforementioned in the introduction, mental well-being has become an important outcome measure in national mental health policy and service provision in many countries, including the UK (8). For example, based on the framework and the agenda of the WHO Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan (37), the European Mental Health Action Plan was formulated with the first main objective: ‘Everyone has an equal opportunity to realize mental well-being throughout their lifespan, particularly those who are most vulnerable or at risk’ (38). Given the recognition and the strong advocacy for mental well-being as an important element in the overall strategy of mental health, it is surprising to see that there have not been many well-designed intervention programmes validated by strong research methodologies and implemented as shown in this systematic review. As such, there is an urgent need to further research into the development and validation of high-quality intervention programmes for enhancing mental well-being among young people. Drawing upon the existing evidence provided by this review, activity-based and psychoeducation intervention would be a reasonable approach for the consideration of future programme development.

There are strengths and limitations in all studies, and so do in this systematic review. The PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews were followed closely to ensure the study’s validity and scientific rigour. Both reviewers observed the criteria for article selection and the procedures stipulated by the guidelines reaffirming the standards of the reviewing processes minimising the selection bias. The employment of the online platform Covidence reduced operational errors and provided a standard approach to data extraction and summarising the extracted information. For the limitations on individual studies, comments were provided in the summary table. Readers can refer to Table 1. Some limitations have been identified in this review study. First, there were too few studies on the topic for conducting a meta-analysis on the effect of the intervention programmes. Second, the sample sizes of most of the included studies were rather small resulting in the possibility in lacking study power to demonstrate a true effect should there be one. Third, in terms of the outcome measure, these trials utilised three different instruments with the WEMWBS being the most common. Although all instrument attempt to assess the construct of mental well-being, there are still some differences among them. This might, in some way, introduce some assessment biases to the study and would possibly explain the differences in the results obtained in different trials. It is recommended that, as far as possible, a standard instrument with the best psychometric properties should be used for future studies.

The current review study has some important contributions to the field of public mental health. Theoretically, the concepts of mental health and mental well-being have been clearly defined and distinguished in this study. The differences between these two concepts should be highlighted for researchers in the field so that scientific pursuits in the understanding of the risk and protective factors of these mental states could be better achieved. In terms of the practical significance, the results of this review have provided some pointers for practitioners in the field in designing future intervention programmes for the enhancement of the mental well-being in young people. In general, programmes adopting a multiple approach of psychoeducation and activities with the employment of the latest communication technologies would be more effective.

In conclusion, this systematic review has examined the available trials on the effect of different intervention programmes on mental well-being among children and adolescents. The results suggest that psychoeducation for positive mental health and psychological well-being and activity-based programme might be effective approaches for intervention. More research on a well-designed programme is urgently needed, particularly in developing countries, to provide good evidence in supporting the mental health policy through the enhancement of mental well-being in young people.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LL and ML were involved in the design of the review, literature search, screening of articles, selection of studies to be reviewed, data extraction, summarizing the information, and drafting and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The allocation of authorship is in accordance with the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) requirements.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that in the conduct of research and the production of the manuscript there are no commercial or financial relationships that could be considered a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Jahoda, M. Current concepts of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books (1958) doi: 10.1037/11258-000

2. WHO. World mental health report: transforming mental health for all. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

3. WHO. Promoting mental health: Concepts, emerging evidence, practice (summary report). Geneva: World Health Organization (2004).

4. Stewart-Brown, S, Samaraweera, PC, Taggart, F, Kandala, NB, and Stranges, S. Socioeconomic gradients and mental health: implications for public health. Br J Psychiatry. (2015) 206:461–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147280

5. Haworth, CM, Carter, K, Eley, TC, and Plomin, R. Understanding the genetic and environmental specificity and overlap between well-being and internalizing symptoms in adolescence. Dev Sci. (2017) 20:e12376. doi: 10.1111/desc.12376

6. Peterson, T. (2021). What is mental wellbeing? Definition and examples, HealthyPlace. Available at https://www.healthyplace.com/self-help/self-help-information/what-mental-wellbeing-definition-and-examples. (Accessed March 10, 2023).

7. de Cates, A, Stranges, S, Blake, A, and Weich, S. Mental well-being: an important outcome for mental health services? Br J Psychiatry. (2015) 207:195–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158329

8. Garratt, K, and Laing, J. Mental health policy in England. London: House of Parliament Library (2022).

9. WHO. Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the Depcare project. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (1998).

10. Keyes, CL. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2005) 73:539–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539

11. Waterman, AS. Two conceptions of happiness: contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1993) 64:678–91. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.678

12. Joshanloo, M, and Weijers, D. A two-dimensional conceptual framework for understanding mental well-being. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0214045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214045

13. Tennant, R, Hiller, L, Fishwick, R, Platt, S, Joseph, S, Weich, S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2007) 5:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

14. Orth, Z, Moosajee, F, and Van Wyk, B. Measuring mental wellness of adolescents: a systematic review of instruments. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:835601. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.835601

15. Purba, A, and Demou, E. The relationship between organisational stressors and mental wellbeing within police officers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1286. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7609-0

16. Bell, SL, Audrey, S, Gunnell, D, Cooper, A, and Campbell, R. The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: a cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2019) 16:138. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0901-7

17. Fancourt, D, and Steptoe, A. The longitudinal relationship between changes in wellbeing and inflammatory markers: are associations independent of depression? Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 83:146–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.10.004

18. Hides, L, Quinn, C, Stoyanov, S, Cockshaw, W, Kavanagh, DJ, Shochet, I, et al. Testing the interrelationship between mental well-being and mental distress in young people. J Posit Psychol. (2020) 15:314–24. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1610478

19. WHO. Adolescent mental health: Mapping actions of nongovernmental organization and other international development organization. Geneva: World Health Organisation (2012).

20. Kauhanen, L, Wan Mohd Yunus, WMA, Lempinen, L, Peltonen, K, Gyllenberg, D, Mishina, K, et al. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2022) 12:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-02060-0

21. WHO. (2019). Mental health. Available at: https://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/child_adolescent/en/. (Accessed September 31, 2022).

22. Barry, MM, Clarke, AM, Jenkins, R, and Patel, V. A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:835. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-835

23. Cahill, SM, Egan, BE, and Seber, J. Activity- and occupation-based interventions to support mental health, positive behavior, and social participation for children and youth: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. (2020) 74:7402180020p1-7402180020p28. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2020.038687

24. Clarke, AM, Kuosmanen, T, and Barry, MM. A systematic review of online youth mental health promotion and prevention interventions. J Youth Adolesc. (2015) 44:90–113. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0165-0

25. Fenwick-Smith, A, Dahlberg, EE, and Thompson, SC. Systematic review of resilience-enhancing, universal, primary school-based mental health promotion programs. BMC Psychology. (2018) 6:30. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0242-3

26. Schmidt, M, Werbrouck, A, Verhaeghe, N, Putman, K, Simoens, S, and Annemans, L. Universal mental health interventions for children and adolescents: a systematic review of health economic evaluations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2020) 18:155–75. doi: 10.1007/s40258-019-00524-0

27. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, and Altman, DG, for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J. (2009) 339:b2535–336. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

28. Tufanaru, C, Munn, Z, Aromataris, E, Campbell, J, and Hopp, L. Systematic reviews of effectiveness In: E Aromataris and Z Munn, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. London, UK: JBI (2020).

29. Calear, AL, Batterham, PJ, Poyser, CT, Mackinnon, AJ, Griffiths, KM, and Christensen, H. Cluster randomised controlled trial of the e-couch anxiety and worry program in schools. J Affect Disord. (2016) 196:210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.049

30. Dowling, K, Simpkin, AJ, and Barry, MM. A cluster randomized-controlled trial of the MindOut social and emotional learning program for disadvantaged post-primary school students. J Youth Adolesc. (2019) 48:1245–63. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-00987-3

31. Hides, L, Dingle, G, Quinn, C, Stoyanov, SR, Zelenko, O, Tjondronegoro, D, et al. Efficacy and outcomes of a music-based emotion regulation mobile app in distressed young people: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019, 2019) 7:e11482. doi: 10.2196/11482

32. Kuroko, S, Black, K, Chryssidis, T, Finigan, R, Hann, C, Haszard, J, et al. Create our own Kai: a randomised control trial of a cooking intervention with group interview insights into adolescent cooking Behaviours. Nutrients. (2020) 12:796. doi: 10.3390/nu12030796

33. Kuyken, W, Ball, S, Crane, C, Ganguli, P, Jones, B, Montero-Marin, J, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision in reducing risk of mental health problems and promoting well-being in adolescence: the MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. Evid Based Ment Health. (2022) 25:99–109. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2021-300396

34. Manicavasagar, V, Horswood, D, Burckhardt, R, Lum, A, Hadzi-Pavlovic, D, and Parker, G. Feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based positive psychology program for youth mental health: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2014) 16:e140. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3176

35. Thabrew, H, Boggiss, AL, Lim, D, Schache, K, Morunga, E, Cao, N, et al. Well-being app to support young people during the COVID-19 pandemic: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J Open. (2022) 12:e058144. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058144

36. Ferreira, ML, Herbert, RD, Ferreira, PH, Latimer, J, Ostelo, RW, Nascimento, DP, et al. A critical review of methods used to determine the smallest worthwhile effect of interventions for low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol. (2012) 65:253–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.018

37. WHO. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. WHA66.8. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013).

Keywords: mental well-being, intervention, children, adolescents, randomised controlled trials, systematic review

Citation: Lam LT and Lam MK (2023) Child and adolescent mental well-being intervention programme: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1106816. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1106816

Edited by:

Yongxin Li, Henan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Shengnan Wang, Henan University, ChinaKai Feng, Henan University, China

Fangzhu Qi, Henan University, China

Copyright © 2023 Lam and Lam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lawrence T. Lam, bHRtbGFtQG11c3QuZWR1Lm1v; TGF3cmVuY2UuTGFtQHN5ZG5leS5lZHUuYXU=

Lawrence T. Lam

Lawrence T. Lam Mary K. Lam

Mary K. Lam