95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 08 February 2023

Sec. Sleep Disorders

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1105840

Background and aims: Excessive use of cell phones can take up college students’ time and energy, and the sleep quality will inevitably be affected. A high level of psychological resilience can help them to maintain a positive attitude and cope with stressful events. However, few studies were conducted to investigate the effects of psychological resilience buffering cell phone addiction on sleep quality. In our hypothesis, psychological toughness would mitigate the worsening impact of cell phone addiction on sleep quality.

Methods: The sample consisted of 7,234 Chinese college students who completed an electronic questionnaire that included demographic characteristics, such as the Mobile Phone Addiction Index (MPAI), the Psychological Resilience Index (CD-RISC), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). SPSS 26.0 was used for data analysis, the measurement data were described by ± s for those conforming to normal distribution, and the comparison of means between groups was analyzed by group t-test or one-way ANOVA. Those that was not conforming to normal distribution were described by median M (P25, P75), and the comparison of M between groups was analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis H test. Using Spearman correlation analysis, the associations between mobile phone addiction, psychological resilience, and sleep quality were evaluated. Using SPSS Process, the mediating role of psychological resilience was examined.

Results: The mean scores of cell phone addiction and psychological resilience were 45.00 (SD = 13.59) and 60.58 (SD = 18.30), respectively; the sleep quality score M (P25, P75) was 5.0 (3.0, 7.0). Cell phone addiction among college students had a direct predictive effect on sleep quality (β = 0.260, P < 0.01), and psychological resilience had a negative correlation with both cell phone addiction and sleep quality (β = –0.073, P < 0.01, and β = –0.210, P < 0.01). Psychological resilience was responsible for a mediating effect value of 5.556% between cell phone addiction and sleep quality.

Conclusion: Cell phone addiction has an impact on sleep quality both directly and indirectly through the mediating effect of psychological resilience. Increased psychological resilience has the potential effect to buffer the exacerbating of cell phone addiction on sleep quality. These findings provide an evidence for cell phone addiction prevention, psychological management, and sleep improvement in China.

Sleep is a fundamental physiological and psychological process for human health (1), and adequate sleep plays a crucial role in developing physical, cognitive, and psychological functions in different populations (2, 3). On the other hand, poor sleep may pose a serious threat to some psychological, physical, and social functioning aspects of individuals, such as cognitive ability, mood, immunity, quality of life, wellbeing, learning, and social interaction (4). It can lead to depression and anxiety (5) and behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption (6). Studies have shown that the prevalence of poor sleep quality and disorders among Chinese university students is 30% (7) and 25.7%, respectively (8). The China Sleep Research Report 2022, published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences on World Sleep Day, reported that more than 90% of Chinese college students had an average (49%) and poor (45%) sleep quality, and more than half of them felt that they did not have enough sleep time. Most of students had the problem of “sleep procrastination.” Sleep is affected by college students’ lifestyle habits, study pressure, and cell phone dependence (9). In addition, study found that approximately 96% of USA undergraduate students reported poor sleep quality (global PSQI score ≥ 6) (10).

College students face some behavioral problems, one of which is cell phone addiction (11). Some researchers have found that young people are more attracted to the latest technology than older people, and smartphones are more attractable to younger generation (12). According to published studies, excessive use of cell phones may lead to physical and mental health problems (13–15). Excessive cell phone use can also lead to addiction and may be associated with sleep disorders (16–18). Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate the relationship between cell phone use and sleep quality among college students. According to the emotion processing model of negative reinforcement, a major reason for maintaining cell phone addiction is the inability of people with problematic cell phone use to deal with the negative emotions that accompany addiction (19). Similarly, several studies have proposed that it is due to individuals’ shortages in regulating negative emotions that cell phone addiction continues to be maintained (20).

Mental health problems among college students are also concerned in the face of pressures related to education, romantic relationships, and employment. One behavior that might harm someone’s mental health and encourage dangerous, but can be buffered by psychological resilience. In theory, psychological resilience includes process, dynamic, competency, and outcome dimensions (21). Psychological resilience is a character quality that protects people from adverse or traumatic experiences, following the paradigm of positive psychology and its calming influence on troublesome behaviors (22). Additionally, psychological resilience places a high value on the potential strength of individuals and pertinent contextual elements, and also helps to shape an individual’s entire growth.

There is evidence that individuals with high psychological resilience have better psychological wellbeing, including higher self-regulation skills, higher self-esteem, and more significant social support. In addition, an individual’s psychological resilience may play an important role in preventing the emergence of problem behaviors (23). Several studies have found that psychological resilience is negatively associated with cell phone addiction (24, 25), as well as some behaviors such as alcohol abuse and eating disorders (26, 27). Based on these studies, psychological resilience may play an important role in preventing the emergence of excessive behaviors.

A prospective study reported that sleep quality was bilaterally associated with psychological resilience, and people with higher psychological resilience had fewer sleep disturbances and shorter sleep latency (28). In addition, a study of adults in the community showed that subjective stress was a risk factor for sleep disorders, while psychological resilience played a protective role against sleep disorders. Furthermore, there was an interaction effect between subjective stress and psychological resilience, with psychological resilience buffering the adverse impacts of subjective stress on sleep (29). Zhou et al. analyzed a study of a college student population and found that psychological resilience may buffer sleep quality on the exacerbating effect of depressive symptoms. According to their findings, the impact of psychological resilience on sleep quality cannot be ignored (30).

However, to date, no studies have explored the role of emotion regulation (e.g., psychological resilience) in the relationship between cell phone addiction and sleep quality. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the buffering capacity of psychological resilience between mobile phone addiction and sleep quality. We proposed two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Psychological resilience, cell phone addiction, and sleep quality of college students are associated with each other.

Hypothesis 2: Psychological resilience of college students mediates the relationship between cell phone addiction and sleep quality.

Based on previous studies, the purpose of this study wasto examine the effect of cell phone addiction on sleep quality, where psychological resilience was the mediating variable. It was hypothesized that cell phone addiction would be related to sleep quality; psychological resilience would mediate the association between cell phone addiction and sleep quality (Figure 1).

An electronic questionnaire-based survey was conducted on the Questionnaire Wenjuanxing platform1 from October 2022 to November 2022. Participants included 7,363 college students (mean age = 18.86 years; SD ± 2.6) through a whole-group convenience sampling from universities in Jiangsu Province, China. Due to incomplete information, 129 participants were excluded from the data set. The final sample set consisted of 7,234 participants (2,157 males and 5,077 females) with a response rate of 98.25%.

Sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (31). Sixteen of the 18 self-rated questions involved in scoring this scale were scored separately (removing the two questions on bedtime and wake-up time), consisting of seven dimensions of sleep onset, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, subjective sleep quality, hypnotic medication, and daytime dysfunction, rated over the last 1 month. The scores of the seven components are summed to produce a PSQI score, where the total score ranges from 0 to 21 (0–3 for each component), with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. The threshold for sleep disturbance is 7. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the PSQI was 0.877, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.926.

Smartphone addiction was assessed using the Mobile Phone Addiction Index (MPAI) (32), which was translated into Chinese and is widely used, validated for Chinese population (33, 34). The MPAI contains 17 items assessing four domains: inability to control craving, feeling anxious and lost, withdrawal/escape, and productivity loss. Each item is responded to from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“always”). Final scores were summed, and higher total scores reflect higher levels of smartphone addiction. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the MPAI was 0.925, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.919.

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) (22) was chosen for this study to measure the level of psychological resilience in college students. The scale has now been developed into several versions and is widely used in different populations and in different situations (35–37). The CD-RISC contains 25 items with responses ranging from 5 points for all items as follows: not true at all (0), rarely true (1), sometimes true (2), usually true (3), and true almost all the time (4). This scale was rated based on how the participant has felt over the past month. The total score ranges from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating more resilience. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the CD-RISC was 0.970, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.979.

SPSS 26.0 was used for statistical analysis. All data were tested for normal distribution using Shapiro–Wilk. The data were described by ± s for those who met the normal distribution by normality test; t-test was used to compare the means between two groups; one-way ANOVA was used to compare the means between multiple groups. The data that did not meet the normal distribution by normality test were described by M (P25, P75), and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for the comparison of M between two groups, and the Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for the comparison of M between multiple groups. Correlations between factors were analyzed using Spearman correlation analysis. Next, we tested the mediating effect of psychological resilience between cell phone addiction and sleep quality using the Bootstrap method (Model 4) with repeated random sampling 5,000 times in the original data to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the mediating effect. A path is significant if the 95% confidence interval does not include 0. P-values under 0.05 are accepted as statistically significant results.

To avoid common method biases, this study was carried out by collecting anonymous responses and scoring some items in reverse. The Harman’s single-factor test was used to conduct exploratory factor analysis on 60 items of the 3 scales, and a total of 10 factors had a characteristic root greater than 1. The variance explained by the first factor was 26.009%, which was less than the critical criterion of 40%. Therefore, the there was no serious common method bias in this study.

Based on 7 as the threshold value for the PQSI, of the 7,234 participants, 6,043 (83.5%) reported normal sleep quality, and 1,191 (16.5%) reported sleep disturbance.

The MPAI, CD-RISC, and PSQI scores of different groups among 7,234 college students are shown in Tables 1–3.

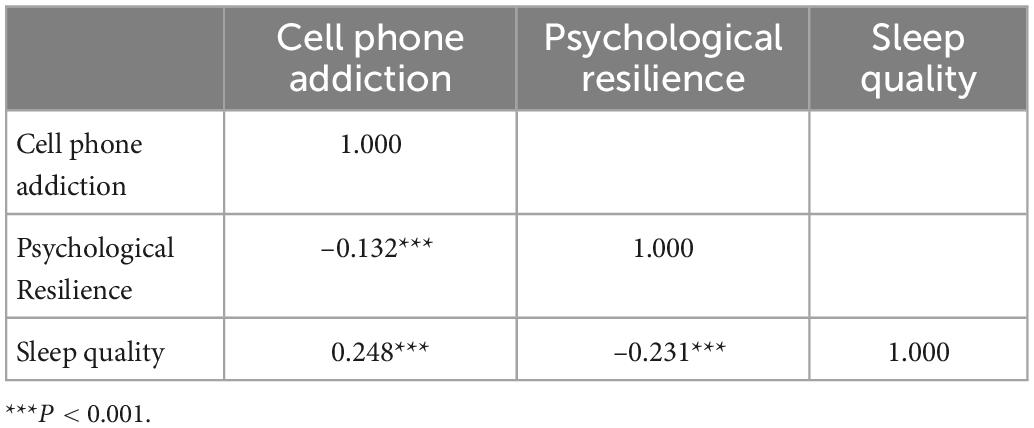

The correlation analysis showed that: cell phone addiction of college students was significantly and positively correlated with sleep quality (rs = 0.248, P < 0.001); cell phone addiction of college students was significantly and negatively correlated with psychological resilience (rs = –0.132, P < 0.001). There was a significant negative correlation between psychological resilience and sleep quality among college students (rs = –0.231, P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation analysis of cell phone addiction, sleep disorder, and psychological resilience among college students (n = 7234).

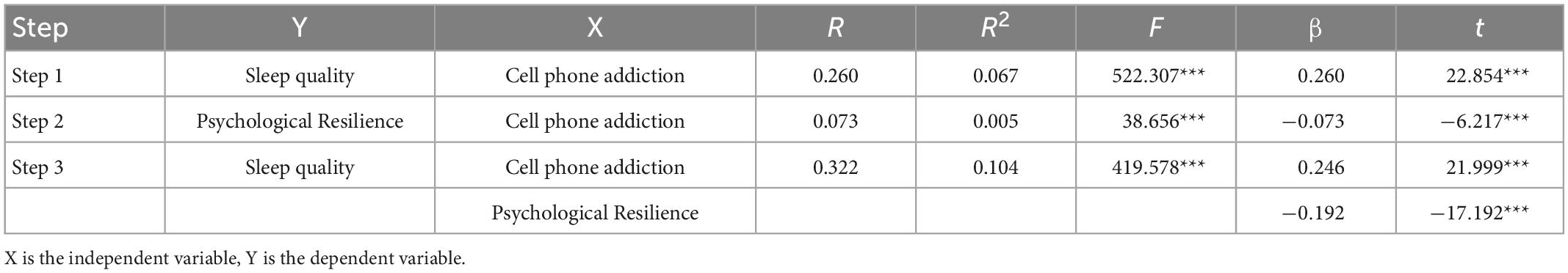

Using sleep quality as the dependent variable, cell phone addiction as the independent variable, and psychological flexibility as the mediating variable. Model 4 in the macro program developed by Hayes was used to test for mediating effects. Based on the bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap method, 95% confidence intervals for the various effects were estimated by sampling 5000 Bootstrap samples, and the mediating effects were significant if the confidence intervals did not include 0.

The results showed that the positive predictive effect of cell phone addiction on sleep quality was significant (β = 0.260, t = 22.854, P < 0.001) and the direct predictive effect of cell phone addiction on sleep quality decreased after putting in mediating variables, but it was still significant (β = 0.246, t = 21.999, P < 0.001). The negative predictive effect of cell phone addiction on psychological resilience was significant (β = –0.073, t = –6.217, P < 0.001). The negative predictive effect of psychological resilience on sleep quality was also significant (β = –0.192, t = 17.192, P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5. Regression analysis of psychological flexibility on cell phone addiction and sleep quality among college students.

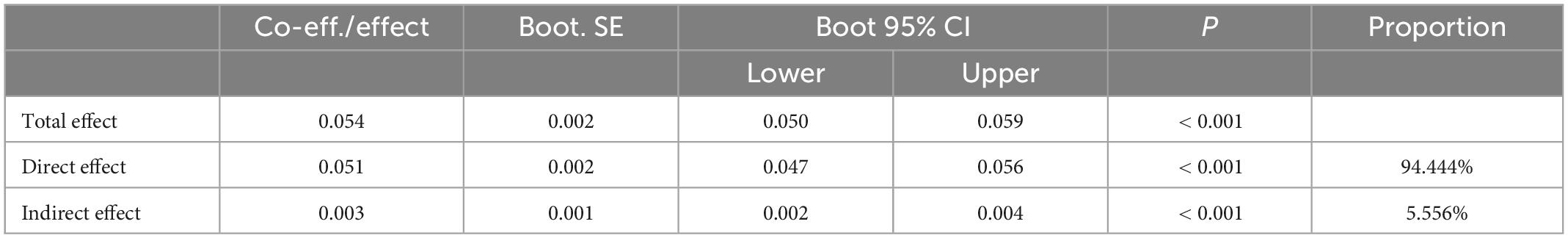

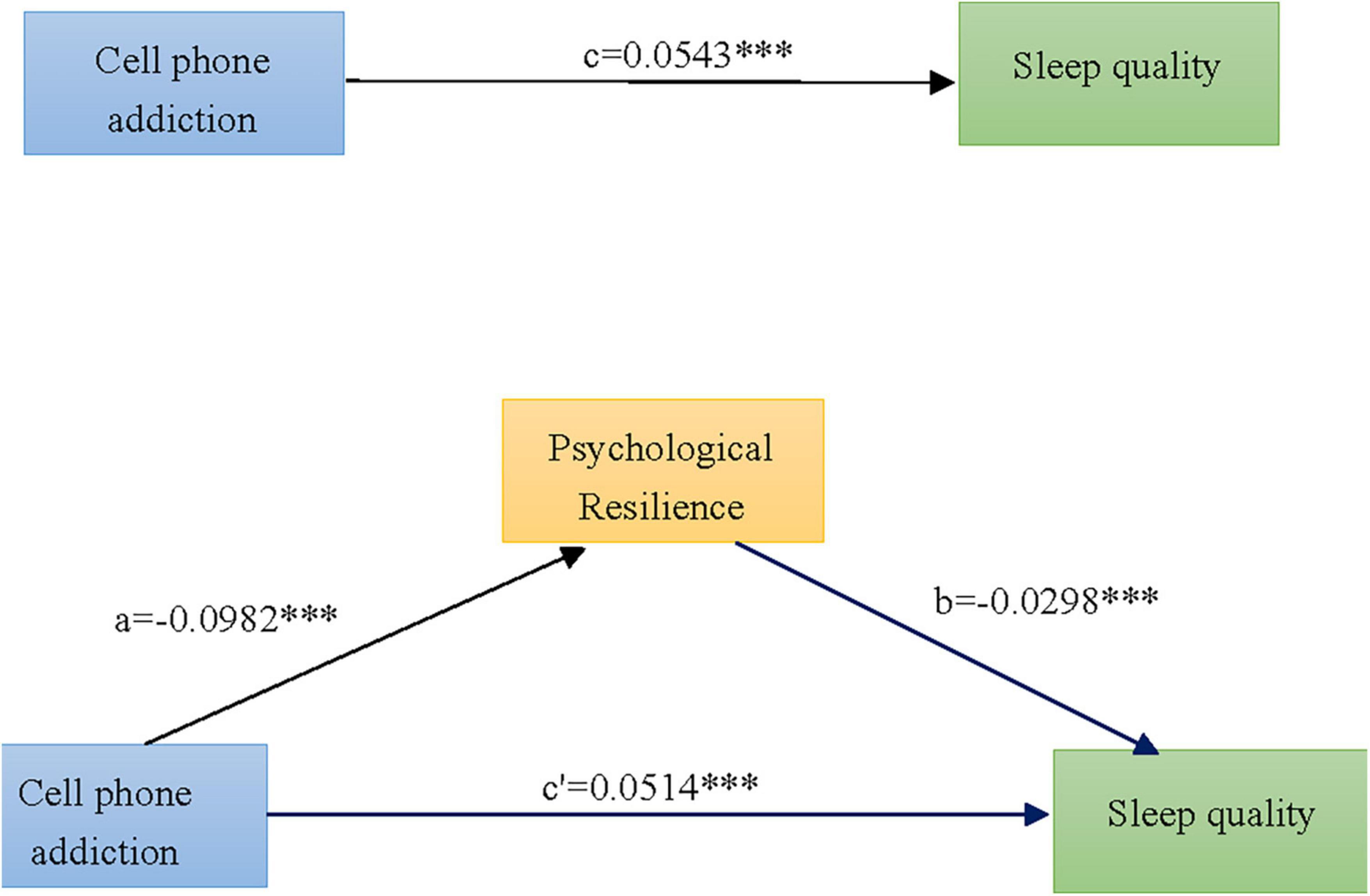

The results of the analysis of the mediation effect showed that the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval corresponding to Bootstrap for each pathway did not contain 0, indicating that psychological resilience played a statistically significant role in mediating the effect between cell phone addiction and sleep quality. Psychological resilience partially mediated the effect between cell phone addiction and sleep quality, with a mediating effect of 5.556% of the total effect size (Table 6). The mediating effect model is shown in Figure 2.

Table 6. Mediating effect test of psychological flexibility between cell phone addiction and sleep quality among college students.

Figure 2. Mediating effect of psychological resilience between cell phone addiction and sleep quality among 7,234 college students. c-Total effect of cell phone addiction on sleep quality; a-Effect of cell phone addiction on the mediating variable psychological flexibility; b-Effect of psychological flexibility on sleep quality after controlling for the effect of cell phone addiction; c′-Direct effect of cell phone addiction on sleep quality after controlling for the effect of psychological flexibility; mediating effect value = a × b. ***P < 0.001.

The current study found that 16.5% of college students had sleep disorders, which is generally consistent with the data derived from previous studies (38). Descriptive analysis found that female students had higher MPAI scores and PSQI scores than male students, which is consistent with the findings of Liu and Lu (39). The study showed that females were more likely to have difficulty in falling asleep, wake up more often at night, and less sleep (40). The PSQI scores of seniors are higher than other grades, while the MPAI scores and CD-RISC scores are lower. It is possible that senior students are facing busy work in internships and employment problems after graduation, which are more psychologically stressful and prone to having sleep problems. Schools should pay more attention to senior students and give guidance in internships and employment or other aspects of life. In college students, the higher frequency of smoking and alcohol consumption, the higher the MPAI score and PSQI score, while the CD-RISC score was not good. The higher frequency of physical activity was associated with lower MPAI and PSQI scores and higher CD-RISC scores, which is consistent with the findings of Lee et al. (41, 42).

The results suggest that psychological resilience partially mediates the relationship between cell phone addiction and sleep quality among college students. The indirect effect of mobile phone addiction on sleep quality through psychological resilience accounted for 5.556% of the total effect, indicating the efficacy of the hypothetical model we constructed. Cell phone addiction predicted sleep quality directly or indirectly, and psychological resilience as a mediating variable can buffer the negative effect of cell phone addiction on sleep quality.

The study showed that college students with high MPAI scores were more likely to have poor sleep quality, which is consistent with the findings of Li et al. (43). There are several explanations for the positive association between cell phone addiction and poor sleep quality. Firstly, excessive cell phone use at bedtime may delay, replace, or disrupt the sleep process. Secondly, excessive cell phone use usually leads to higher levels of psychological stress, which also negatively affects sleep and recovery. Thirdly, the blue light emitted from the screen may affect melatonin levels, which can interfere with sleep. Finally, electromagnetic fields emitted by cell phones may also contribute to poor sleep quality (14). Among college students, cell phone addiction to some extent reflects the lack of self-control. College students are more likely to use cell phones excessively at night due to many courses and heavy tasks during the day, which shortens the sleep time. The light from cell phone screens inhibits melatonin secretion at night, disrupting the circadian rhythm of the body and leading to difficulties in falling asleep. At the same time, cell phone addiction among college students can also lead to poor concentration in class or reduced study time and study pressure, which can lead to negative emotions such as anxiety and reduced sleep quality.

To date, lots of studies have investigated risk factors for sleep quality. However, in recent years, psychological resilience (the ability to thrive in the face of adversity) has received increasing attention as a counteracting factor to stress, thus contributed greatly to recovery from adverse situations (44). Cell phones as mobile Internet carriers consume the psychological resources of college students in various ways, and their excessive use may affect emotional balance by disrupting self-control (45). Wang et al. (46) noted that cell phone addiction can lead to increased negative emotions. Similarly, some researchers have suggested that it is due to individuals’ deficits in regulating negative emotions that cell phone addiction continues to be maintained (20). Furthermore, research has shown that individuals with cell phone addiction are more likely to have difficulties with emotion regulation (47). Therefore, college students with cell phone addiction may frequently experience negative emotions and have low levels of psychological resilience. Young people with low psychological resilience are prone to having sleep disorders. On the contrary, young people with high psychological resilience are good at resolving various adverse events in life, work and study, and presenting good sleep quality (28). The reason for this may be that college students with high levels of psychological resilience can mitigate neurohormonal changes in their bodies and thus can have a positive impact on sleep quality. Another reason may be that individuals with positive psychological characteristics have a positive effect on their sleep quality by having good physical and mental health. In conclusion, psychological resilience is a protective factor for good sleep quality among college students, and can buffer the relationship between college students’ cell phone addiction and sleep quality.

This study reveals the mediating role of psychological resilience behind the relationship between college students’ cell phone addiction and sleep quality, which suggests that college educators can use emotional regulation and improved emotional control ability to solve this problem when intervening in college students’ cell phone addiction. This can be done by developing college students’ psychological resilience and tapping protective resources to buffer their pathological cell phone addiction. It can also be done by developing psychological resilience to improve the negative emotions of cell phone addicted college students and improve their sleep quality. Some studies have shown that the neurotransmitter endorphin in the brain (48) can change the negative emotions of individuals, which can reduce stress, relieve tension and bad emotional state. Certain intensity of exercise can also promote the secretion of endorphin in the brain, such as running and swimming (49). The current study also showed that the more frequent physical exercise, the lower MPAI and PSQI scores and the higher CD-RISC scores, which fully proved the benefits brought by proper exercise. College psychologists can also guide college students to use cognitive reappraisal (50) (change the understanding of emotional events and change the perception of their personal meaning) through individual counseling or group counseling to reduce their reactions to and experiences of negative events (cell phone addiction). They can guide them to maintain their psychological resilience through reasonable regulation of emotional catharsis, reduce college students’ dependence on mobile phones and improve their sleep status. Last but not least, this study was implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the epidemic had an impact on the physical and mental health as well as the sleep status of college students over the past 3 years. Acute stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms have been prevalent among college students during the COVID-19 epidemic (51, 52). Therefore, future investigations are necessary to validate the conclusions drawn from this study.

There are several limitations to our study. Firstly, this was a sample based on a population of college students, which may be the main limitation comparing to other studies. Further research could expand the scope of the study population. Secondly, the data are just from one province, the results and conclusions may be influenced by local sociological factors. There is a serious cause for constant stress due to the very strict COVID-19 regulations in China, the comparison to other regions will be limited, and our results might be hardly transferable to other countries. Finally, our current study only considered psychological resilience, but there are still other factors that may mediate the association between cell phone addiction and sleep quality. Therefore, we suggest that future studies can consider anxiety, loneliness, and depression. Despite these limitations, this study examined the parallel mediating role of psychological resilience on the relationship between cell phone addiction and sleep quality. It also provides new intervention strategies from a psychological resilience perspective to buffer the negative effects of cell phone addiction on sleep quality.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

QW and XG analyzed the data. QW, GX, JZ, and DY conceived and designed the study. QW drafted the manuscript. DY reviewed and made improvements in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by special research project of philosophy, social science, ideology, and politics of Jiangsu Colleges and Universities (Grant number 2021SJB0516) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 81802101).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Zhang J, Xu Z, Zhao K, Chen T, Ye X, Shen Z, et al. Sleep habits, sleep problems, sleep hygiene, and their associations with mental health problems among adolescents. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. (2018) 24:223–34. doi: 10.1177/1078390317715315

2. Sadeghi Bahmani D, Esmaeili L, Shaygannejad V, Gerber M, Kesselring J, Lang U, et al. Stability of mental toughness, sleep disturbances, and physical activity in patients with multiple sclerosis (Ms)-a longitudinal and pilot study. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:182. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00182

3. Ramos J, Muraro A, Nogueira P, Ferreira M, Rodrigues P. Poor sleep quality, excessive daytime sleepiness and association with mental health in college students. Ann Hum Biol. (2021) 48:382–8. doi: 10.1080/03014460.2021.1983019

4. Owens J. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: an update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics. (2014) 134:e921–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1696

5. Alrashed F, Alsubiheen A, Alshammari H, Mazi S, Al-Saud S, Alayoubi S, et al. Stress, anxiety, and depression in pre-clinical medical students: prevalence and association with sleep disorders. Sustainability. (2022) 14:11320. doi: 10.3390/su141811320

6. Sirtoli R, Balboa-Castillo T, Fernández-Rodríguez R, Rodrigues R, Morales G, Garrido-Miguel M, et al. The association between alcohol-related problems and sleep quality and duration among college students: a multicountry pooled analysis. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2022):1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11469-022-00763-8

7. Li Y, Bai W, Zhu B, Duan R, Yu X, Xu W, et al. Prevalence and correlates of poor sleep quality among college students: a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2020) 18:210. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01465-2

8. Li L, Wang Y, Wang S, Zhang L, Li L, Xu D, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in Chinese university students: a comprehensive meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. (2018) 27:e12648. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12648

9. Wang J, Zhang Y, Liu Y. Annual Sleep Report of China 2022. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press (2022). p. 244.

10. Joshi S. Sleep latency and sleep disturbances mediates the association between nighttime cell phone use and psychological well-being in college students. Sleep Biol Rhythms. (2022) 20:431–43. doi: 10.1007/s41105-022-00388-3

11. Shoukat S. Cell phone addiction and psychological and physiological health in adolescents. EXCLI J. (2019) 18:47–50.

12. Parasuraman S, Sam A, Yee S, Chuon B, Ren L. Smartphone usage and increased risk of mobile phone addiction: a concurrent study. Int J Pharm Invest. (2017) 7:125–31. doi: 10.4103/jphi.JPHI_56_17

13. Zarghami M, Khalilian A, Setareh J, Salehpour G. The impact of using cell phones after light-out on sleep quality, headache, tiredness, and distractibility among students of a university in north of Iran. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. (2015) 9:e2010. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs-2010

14. Demirci K, Akgönül M, Akpinar A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J Behav Addict. (2015) 4:85–92. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.010

15. Matar Boumosleh J, Jaalouk D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students- a cross sectional study. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0182239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182239

16. Mohammadbeigi A, Absari R, Valizadeh F, Saadati M, Sharifimoghadam S, Ahmadi A, et al. Sleep quality in medical students; the impact of over-use of mobile cell-phone and social networks. J Res Health Sci. (2016) 16:46–50.

17. Lee J, Jang S, Ju Y, Kim W, Lee H, Park E. Relationship between Mobile phone addiction and the incidence of poor and short sleep among Korean adolescents: a longitudinal study of the Korean children & youth panel survey. J Korean Med Sci. (2017) 32:1166–72. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.7.1166

18. Xie Y, Cheung D, Loke A, Nogueira B, Liu K, Leung A, et al. Relationships between the usage of televisions, computers, and mobile phones and the quality of sleep in a Chinese population: community-based cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e18095. doi: 10.2196/18095

19. Baker T, Piper M, McCarthy D, Majeskie M, Fiore M. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol Rev. (2004) 111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.111.1.33

20. Strittmatter E, Parzer P, Brunner R, Fischer G, Durkee T, Carli V, et al. A 2-year longitudinal study of prospective predictors of pathological internet use in adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2016) 25:725–34. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0779-0

21. Masten A. Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: frameworks for research, practice, and translational synergy. Dev Psychopathol. (2011) 23:493–506. doi: 10.1017/s0954579411000198

22. Connor K, Davidson J. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (Cd-Risc). Depress Anxiety. (2003) 18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113

23. Shen X. Is psychological resilience a protective factor between motivations and excessive smartphone use? J Pac Rim Psychol. (2020) 14:e17. doi: 10.1017/prp.2020.10

24. Kuru T, Çelenk S. The relationship among anxiety, depression, and problematic smartphone use in university students: the mediating effect of psychological inflexibility. Anatolian J Psychiatry. (2021) 22:159–64. doi: 10.5455/apd.136695

25. Shi Z, Guan J, Chen H, Liu C, Ma J, Zhou Z. Teacher-student relationships and smartphone addiction: the roles of achievement goal orientation and psychological resilience. Curr Psychol. (2022):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02902-9

26. Green K, Beckham J, Youssef N, Elbogen E. Alcohol misuse and psychological resilience among U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan era veterans. Addict Behav. (2014) 39:406–13. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.024

27. Las Hayas C, Calvete E, Gómez del Barrio A, Beato L, Muñoz P, Padierna J. Resilience scale-25 Spanish version: validation and assessment in eating disorders. Eat Behav. (2014) 15:460–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.06.010

28. Wang J, Zhang X, Simons S, Sun J, Shao D, Cao F. Exploring the Bi-directional relationship between sleep and resilience in adolescence. Sleep Med. (2020) 73:63–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.018

29. Liu X, Liu C, Tian X, Zou G, Li G, Kong L, et al. Associations of perceived stress, resilience and social support with sleep disturbance among community-dwelling adults. Stress Health. (2016) 32:578–86. doi: 10.1002/smi.2664

30. Zhou J, Hsiao F, Shi X, Yang J, Huang Y, Jiang Y, et al. Chronotype and depressive symptoms: a moderated mediation model of sleep quality and resilience in the 1st-year college students. J Clin Psychol. (2021) 77:340–55. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23037

31. Buysse D, Reynolds C III, Monk T, Berman S, Kupfer D. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

32. Bianchi A, Phillips J. Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2005) 8:39–51. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.39

33. Li L, Griffiths M, Mei S, Niu Z. Fear of missing out and smartphone addiction mediates the relationship between positive and negative affect and sleep quality among Chinese university students. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:877. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00877

34. An X, Chen S, Zhu L, Jiang C. The mobile phone addiction index: cross gender measurement invariance in adolescents. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:894121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.894121

35. Xu C, Wang Y, Wang Z, Li B, Yan C, Zhang S, et al. Social support and coping style of medical residents in China: the mediating role of psychological resilience. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:888024. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.888024

36. Tourunen A, Siltanen S, Saajanaho M, Koivunen K, Kokko K, Rantanen T. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson resilience scale among Finnish older adults. Aging Ment Health. (2021) 25:99–106. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1683812

37. Levey E, Rondon M, Sanchez S, Williams M, Gelaye B. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the 10-item Connor Davidson resilience scale (Cd-Risc) among adolescent mothers in Peru. J Child Adolesc Trauma. (2021) 14:29–40. doi: 10.1007/s40653-019-00295-9

38. Wu Q, Yuan L, Guo X, Li J, Yin D. Study on lifestyle habits affecting sleep disorders at the undergraduate education stage in Xuzhou City, China. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:1053798. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1053798

39. Liu M, Lu C. Mobile phone addiction and depressive symptoms among Chinese university students: the mediating role of sleep disturbances and the moderating role of gender. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:965135. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.965135

40. Becker S, Jarrett M, Luebbe A, Garner A, Burns G, Kofler M. Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health. (2018) 4:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.01.001

41. Liu H, Zhang C, Ji Y, Yang L. Biological and psychological perspectives of resilience: is it possible to improve stress resistance? Front Hum Neurosci. (2018) 12:326. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00326

42. Lee P, Tse A, Wu C, Mak Y, Lee U. Temporal association between objectively measured smartphone usage, sleep quality and physical activity among Chinese adolescents and young adults. J Sleep Res. (2021) 30:e13213. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13213

43. Li Y, Li G, Liu L, Wu H. Correlations between mobile phone addiction and anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and poor sleep quality among college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Addict. (2020) 9:551–71. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00057

44. Terao I, Masuya J, Morishita C, Higashiyama M, Shimura A, Tamada Y, et al. Resilience moderates the association of sleep disturbance and sleep reactivity with depressive symptoms in adult volunteers. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2022) 18:1249–57. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S361353

45. Li X, Feng X, Xiao W, Zhou H. Loneliness and mobile phone addiction among Chinese college students: the mediating roles of boredom proneness and self-control. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2021) 14:687–94. doi: 10.2147/prbm.S315879

46. Wang W, Mehmood A, Li P, Yang Z, Niu J, Chu H, et al. Perceived stress and smartphone addiction in medical college students: the mediating role of negative emotions and the moderating role of psychological capital. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:660234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660234

47. Fu L, Wang P, Zhao M, Xie X, Chen Y, Nie J, et al. Can Emotion regulation difficulty lead to adolescent problematic smartphone use? A moderated mediation model of depression and perceived social support. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 108:104660. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104660

48. Hawkes C. Endorphins: the basis of pleasure? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1992) 55:247–50. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.4.247

49. Schoenfeld T, Swanson C. A runner’s high for new neurons? Potential role for endorphins in exercise effects on adult neurogenesis. Biomolecules. (2021) 11:1077. doi: 10.3390/biom11081077

50. Hartanto A, Wong J, Lua V, Tng G, Kasturiratna K, Majeed N. A daily diary investigation of the fear of missing out and diminishing daily emotional well-being: the moderating role of cognitive reappraisal. Psychol Rep. (2022):332941221135476. doi: 10.1177/00332941221135476

51. Wang R, He L, Xue B, Wang X, Ye S. Sleep quality of college students during covid-19 outbreak in China: a cross-sectional study. Altern Ther Health Med. (2022) 28:58–64.

Keywords: cell phone addiction, psychological resilience, sleep quality, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, mobile phone addiction

Citation: Xie G, Wu Q, Guo X, Zhang J and Yin D (2023) Psychological resilience buffers the association between cell phone addiction and sleep quality among college students in Jiangsu Province, China. Front. Psychiatry 14:1105840. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1105840

Received: 23 November 2022; Accepted: 23 January 2023;

Published: 08 February 2023.

Edited by:

Helena Martynowicz, Wrocław Medical University, PolandReviewed by:

Gniewko Więckiewicz, Medical University of Silesia, PolandCopyright © 2023 Xie, Wu, Guo, Zhang and Yin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dehui Yin,  eWluZGgxNkB4emhtdS5lZHUuY24=

eWluZGgxNkB4emhtdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.