94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 16 March 2023

Sec. Mood Disorders

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1078045

Keita Tokumitsu1

Keita Tokumitsu1 Norio Yasui-Furukori1,2*

Norio Yasui-Furukori1,2* Naoto Adachi3

Naoto Adachi3 Yukihisa Kubota3

Yukihisa Kubota3 Yoichiro Watanabe3

Yoichiro Watanabe3 Kazuhira Miki3

Kazuhira Miki3 Takaharu Azekawa3

Takaharu Azekawa3 Koji Edagawa3

Koji Edagawa3 Eiichi Katsumoto3

Eiichi Katsumoto3 Seiji Hongo3

Seiji Hongo3 Eiichiro Goto3

Eiichiro Goto3 Hitoshi Ueda3

Hitoshi Ueda3 Masaki Kato2,4

Masaki Kato2,4 Atsuo Nakagawa2,5

Atsuo Nakagawa2,5 Toshiaki Kikuchi2,6

Toshiaki Kikuchi2,6 Takashi Tsuboi2,7

Takashi Tsuboi2,7 Koichiro Watanabe2,7

Koichiro Watanabe2,7 Kazutaka Shimoda1

Kazutaka Shimoda1 Reiji Yoshimura2,8

Reiji Yoshimura2,8Background: Bipolar disorder is a psychiatric disorder that causes recurrent manic and depressive episodes, leading to decreased levels of social functioning and suicide. Patients who require hospitalization due to exacerbation of bipolar disorder have been reported to subsequently have poor psychosocial functioning, and so there is a need to prevent hospitalization. On the other hand, there is a lack of evidence regarding predictors of hospitalization in real-world clinical practice.

Methods: The multicenter treatment survey on bipolar disorder (MUSUBI) in Japanese psychiatric clinics was an observational study conducted to provide evidence regarding bipolar disorder in real-world clinical practice. Psychiatrists were asked, as part of a retrospective medical record survey, to fill out a questionnaire about patients with bipolar disorder who visited 176 member clinics of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics. Our study extracted baseline patient characteristics from records dated between September and October 2016, including comorbidities, mental status, duration of treatment, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score, and pharmacological treatment details. The incidence and predictors of hospitalization among patients with bipolar disorder over a 1-year period extending from that baseline to September–October 2017 were examined.

Results: In total, 2,389 participants were included in our study, 3.06% of whom experienced psychiatric hospitalization over the course of 1 year from baseline. Binomial logistic regression analysis revealed that the presence of psychiatric hospitalization was correlated with bipolar I disorder, lower baseline GAF scores, unemployment, substance abuse and manic state.

Conclusions: Our study revealed that 3.06% of outpatients with bipolar disorder were subjected to psychiatric hospitalization during a 1-year period that extended to September–October 2017. Our study suggested that bipolar I disorder, lower baseline GAF scores, unemployment, substance abuse and baseline mood state could be predictors of psychiatric hospitalization. These results may be useful for clinicians seeking to prevent psychiatric hospitalization for bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder is a psychiatric disorder with recurrent manic and depressive episodes (1–3). Bipolar disorder is classified into bipolar I disorder, which presents with manic episodes accompanied by severe psychosocial dysfunction, and bipolar II disorder, which presents with both hypomanic and depressive episodes, based on the DSM-5 criteria (3, 4). The annual prevalence of bipolar disorder is as high as ~2% (5), complications with other psychiatric and physical illnesses are reported, and there is an increased risk of suicide (5). Treatment is difficult. It has been noted that 30–60% of patients with bipolar disorder do not recover to their preonset level of functioning after achieving remission, and functional impairment has also been reported to be associated with high unemployment rates (6). A recent study has shown that the clinical course is a predictor of functional recovery, particularly that a high number of hospitalizations and being manic at baseline are predictors of subsequent worsening of functional impairment (7). In addition, concomitant use of psychotropic medications other than mood stabilizers has been found to be statistically significant as a predictor of both long-term hospitalization (8) and early readmission (9) in patients with bipolar disorder. On the other hand, a 1-year naturalistic cohort study at a single institution found no association between rehospitalization and any type of drug regimen, suggesting the equal effectiveness of individually optimized pharmacotherapy regimens for patients with bipolar disorder (10). There are also reports that bipolar I disorder is associated with a higher risk of psychiatric hospitalization than bipolar II disorder (11) and that comorbid substance use disorder is a predictor of psychiatric hospitalization (12). Furthermore, hospitalization and functional impairment in bipolar disorder are known to lead to increased social costs as well as patient distress (13). Therefore, preventing hospitalization, reducing the risk of recurrence of psychiatric symptoms, and improving patients' Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores have been shown to be important from a health economic perspective for bipolar disorder (13). However, most studies on predictors of hospitalization for bipolar disorder have been single-center studies or reports of patients from Western countries. Therefore, there is insufficient real-world clinical evidence on the risk of hospitalization for patients with bipolar disorder in other regions including Asia.

In Japan, more than 90% of patients with mood disorders are outpatients, and approximately half of them is treated at clinics belonging to the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics (JAPC) (14). In this study, we conducted an observational study of outpatients with bipolar disorder in coordination with the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics and the Japanese Society of Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology (MUlticenter treatment SUrvey on BIpolar disorder in Japanese psychiatric clinics, or MUSUBI) (14–23). Since psychiatric clinics do not have inpatient beds, physicians affiliated with the clinics are highly interested in predictors of hospitalization in order to stabilize patients' mental status and prevent psychiatric hospitalization. We investigated the yearly rate of hospitalization and predictive factors for hospitalization among outpatients with bipolar disorder. This study is a post-hoc analysis using the same population as our previously published article (15).

The MUSUBI study was a retrospective study in which a questionnaire was administered at 176 outpatient clinics belonging to the JAPC with baseline patient characteristics data collected from September to October 2016 (14). We investigated the occurrence of psychiatric hospitalization over the course of 1 year extending from baseline to September–October 2017. The subjects used in this study are the same population as in our previously published article (15). Patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder based on the ICD-10 (2) and the DSM-5 (3) criteria and treated at these clinics were included in the study.

Clinical psychiatrists were asked to complete a semistructured questionnaire on patients with bipolar disorder by performing a retrospective medical record survey. The questionnaire included patient characteristics (age, sex, height, weight, educational background, and work status), comorbidities, mental status, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score, and details of pharmacological treatment as the baseline data. In addition, we assessed the occurrence of psychiatric hospitalization over the course of the year after baseline.

All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corporation, Version 28.0.0.0) and EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) (24). The EZR provides a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 4.0.3). More precisely, it is a modified version of R Commander (version 2.7–1) that incorporates statistical functions frequently used in biostatistics.

All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05. Demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed using the chi-square test and the Student's t-test to identify differences between patients with and without psychiatric hospitalization over the course of the year after baseline. Bivariate analyses were performed to assess demographic and clinical features. In addition, the association between psychiatric hospitalization and the combination of prescriptions for mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and antidepressants was analyzed with the chi-square test. All factors of demographic and clinical characteristics associated with the occurrence of psychiatric hospitalization among bipolar disorder patients were identified using binomial logistic regression with forced entry to avoid overlooking any potential associations. These factors included sex, body mass index (BMI), age at study entry, age at the onset of bipolar symptoms, current employment status, education level, mood stabilizer prescription (valproic acid, lithium carbonate, carbamazepine and lamotrigine), antipsychotic prescription, anxiolytic (benzodiazepine only) prescription, hypnotic prescription, intelligence quotient (IQ), GAF score, psychiatric comorbidities, personality disorder, developmental disorder, physical comorbidities, rapid cycling status, substance abuse (alcohol abuse), suicidal ideation, types of bipolar disorder and mood status. Intellectual disability was not included in developmental disabilities.

The following dummy variables of each factor were included in the binomial logistic regression analysis: male = 0, female = 1; employed = 1, unemployed = 0; educational background (special support education school or junior high school = 0, high school or vocational school = 1, junior college, technical college, university, master's degree or higher = 2); taking mood stabilizers = 1, not taking mood stabilizers = 0; taking antipsychotics = 1, not taking antipsychotics = 0; taking anxiolytics = 1, not taking anxiolytics = 0; taking hypnotics = 1, not taking hypnotics = 0; IQ (>85) = 0, IQ (<85) = 1; GAF (81–100) = 0, GAF (61–80) = 1, GAF (41–60) = 2, GAF (<41) = 3; psychiatric comorbidity = 1, no psychiatric comorbidity = 0; personality disorder = 1, no personality disorder = 0; developmental disorder = 1, no developmental disorder = 0; physical comorbidity = 1, no physical comorbidity = 0; rapid cycling = 1, no rapid cycling = 0; substance abuse (alcohol abuse) = 1, no substance abuse (no alcohol abuse) = 0; and suicidal ideation = 1, no suicidal ideation = 0. Four mood states (depressive, mixed, remission and manic/hypomanic) and types of bipolar disorders (bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder and bipolar disorder unclassifiable) were analyzed as nominal measures. A bipolar disorder not otherwise specified was listwise deleted; patients with serious physical conditions such as terminal cancer or intractable diseases were excluded. Cases with missing values in the questionnaire responses were also excluded. Other factors were not exclusionary for patients in this study.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. Prior to the initiation of the study, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of JAPC and Dokkyo Medical University School of Medicine (Approval No. 20160822, 2017-3). Since this was a retrospective medical record survey, it was exempted from the requirement for informed consent; however, we released information on this research so that patients were free to opt out. Administrative permissions and licenses were acquired by our team to access the data used. The ethics committee of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics set restrictions on data sharing because of potentially identifying or sensitive patient information. Please contact the institutional review board of the ethics committee when requesting data. Contact information for our ethics committee is as follows: The Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics; Shibuya-ku, Yoyogi 1-38-2, Tokyo Metropolis, Japan, Postal Code 151–0053, Phone +81-3-3320-1423.

Representing baseline data, completed questionnaires on 3,137 outpatients with bipolar disorder were returned from the 176 originally solicited outpatient facilities. A total of 748 outpatients were excluded with listwise deletions due to missing values. Thus, data regarding a total of 2,389 patients were included in this study. The sociodemographic characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

The proportion of patients who experienced psychiatric hospitalization over the course of the year after baseline was 3.06% (73/2,389). The results of the bivariate analysis are shown in Table 1. Because 24 comparisons were made, a Bonferroni correction was applied, yielding a corrected significance criterion of p < 0.0021 in bivariate analyses. Based on this threshold, the occurrence of psychiatric hospitalization significantly differed among the groups stratified by GAF scores, suicidal ideation, employment status, types of bipolar disorders, mood status at baseline and substance abuse (alcohol abuse).

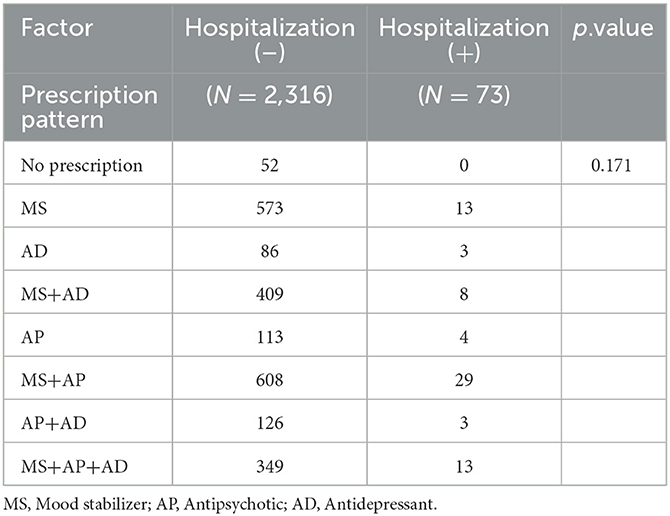

In addition, the combination of mood stabilizers, antipsychotics and antidepressants was not statistically significantly associated with psychiatric hospitalization in patients with bipolar disorder in this study (p = 0.171) (Table 2).

Table 2. Prescription pattern among antidepressant, mood stabilizer, and antipsychotic prescriptions.

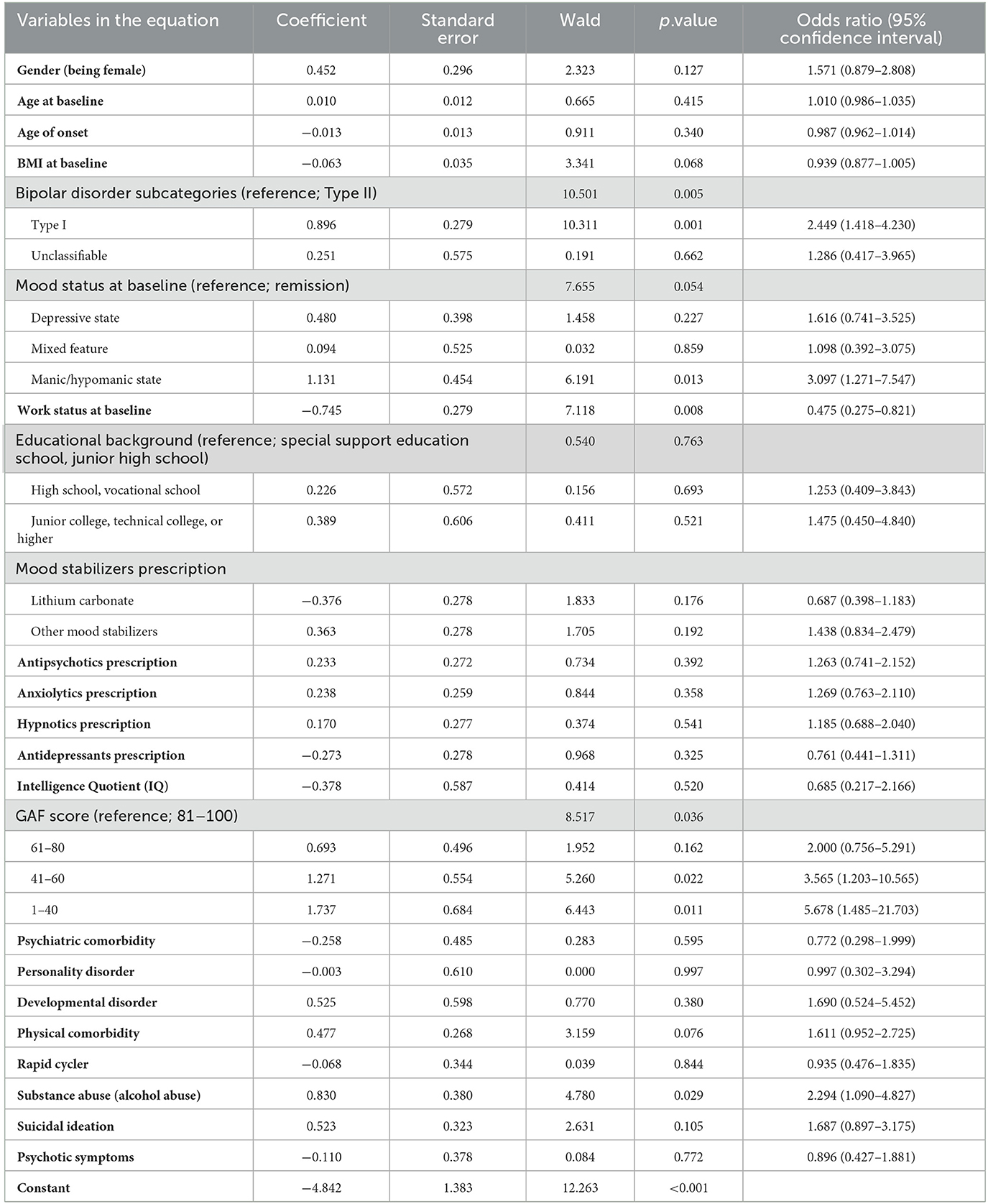

A binomial logistic regression analysis revealed that there were significantly lower GAF scores in the group of patients with psychiatric hospitalization during the year after baseline [GAF 41–60, OR (95% CI) = 3.565 (1.203–10.565), p = 0.022; GAF 1–40, OR (95% CI) = 5.678 (1.485–21.703), p = 0.011]; the group also had a higher proportion of patients with bipolar I disorder rather than bipolar II disorder [OR = 2.449 (1.418–4.230), p = 0.001] as well as higher proportions of patients with unemployment [OR = 0.475 (0.275–0.821), p = 0.008], and substance abuse (alcohol abuse) [OR = 2.294 (1.090–4.827), p = 0.029]. The group of patients in a manic/hypomanic state [OR = 3.097 (1.271–7.547), p = 0.013] had significantly higher proportions of patients with psychiatric hospitalization than the group where patients were in a state of remission (Table 3). Multicollinearity between variables was not observed in our binomial logistic regression analysis with a forced entry model.

Table 3. Binomial logistic regression analysis of factors for psychiatric hospitalization among all patients.

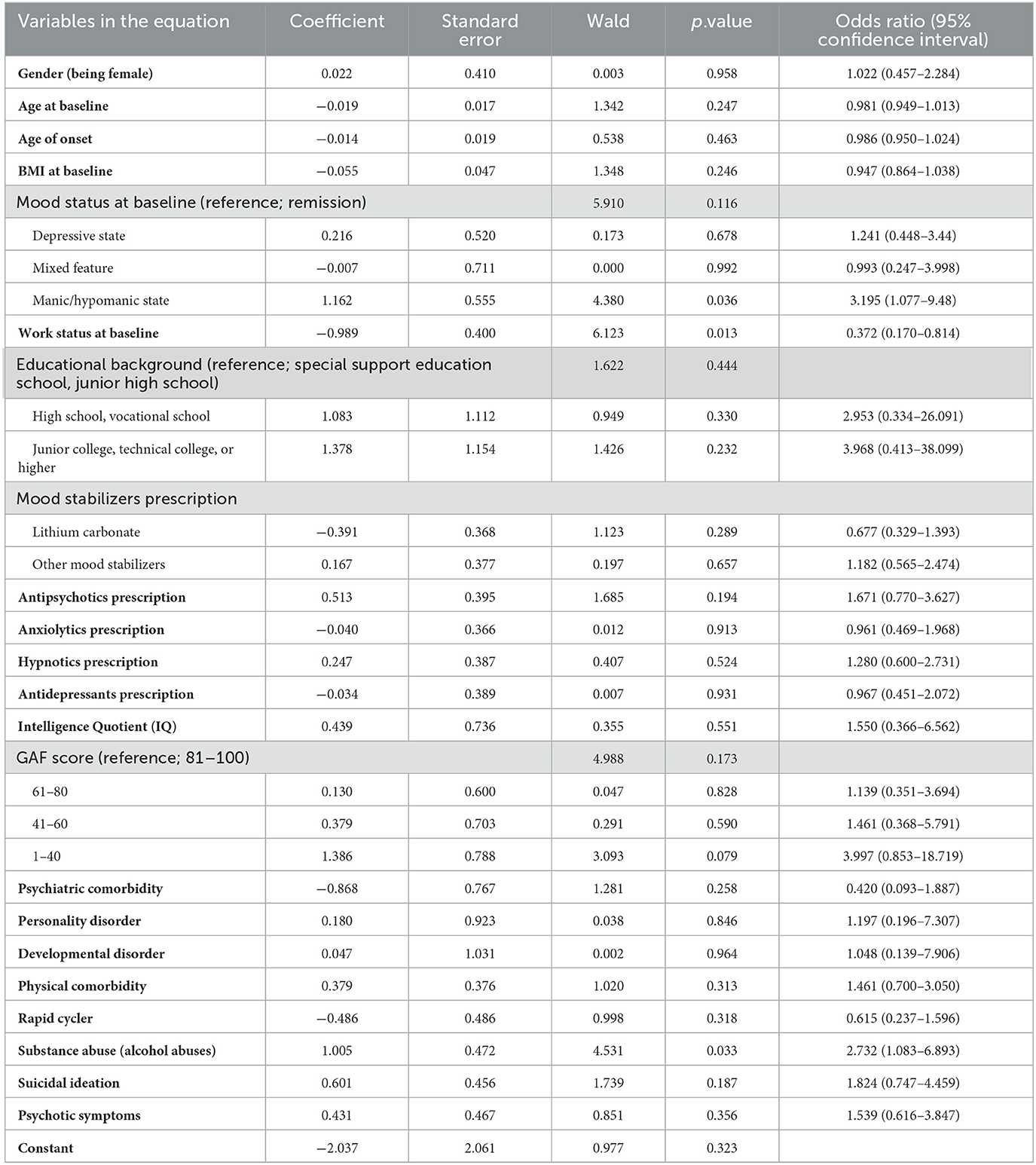

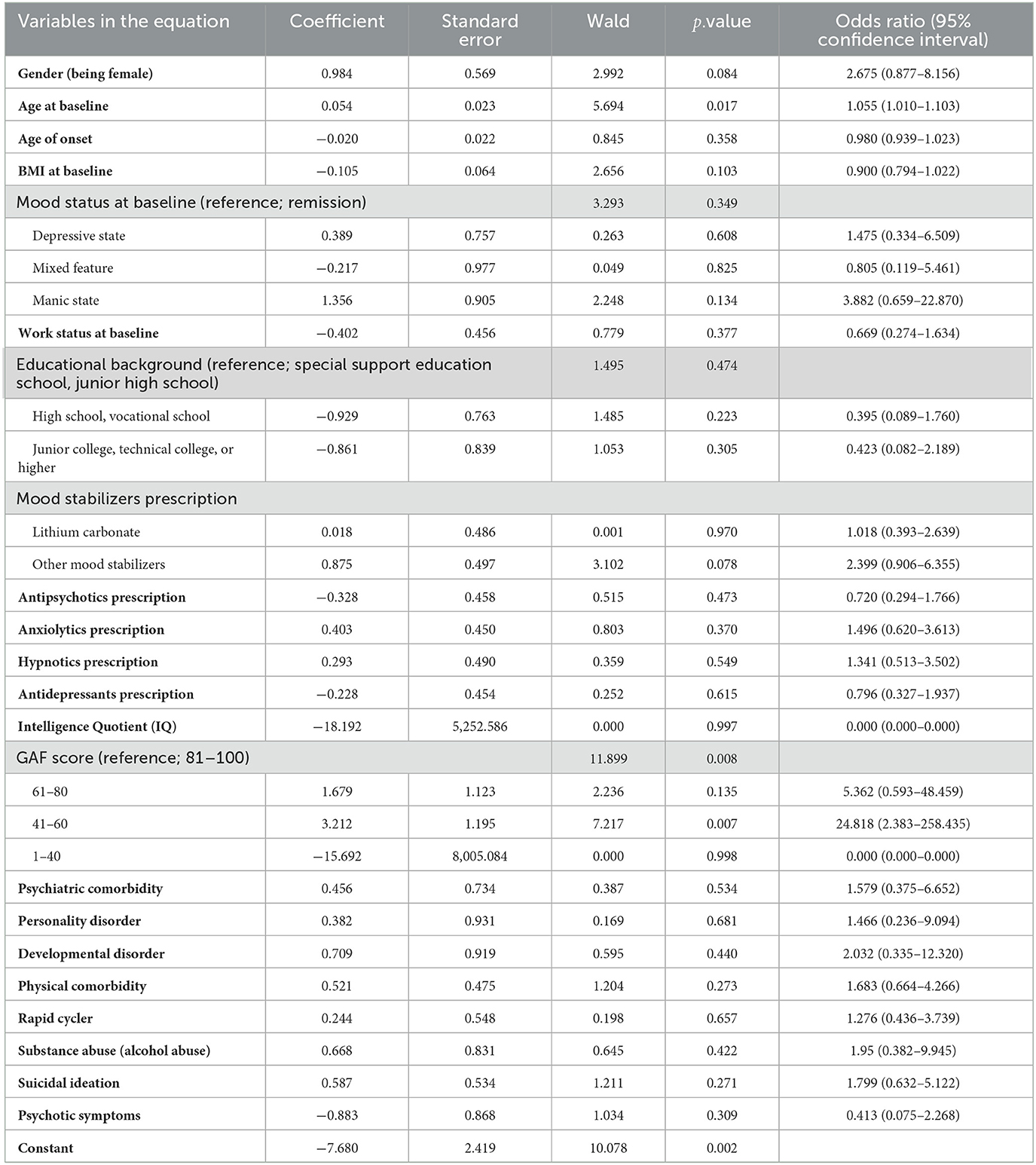

In addition, we stratified patients with bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder, and analyzed the predictors of hospitalization in each population using binomial logistic regression analysis.

The results showed that a manic/hypomanic state at baseline, unemployment and substance abuse (alcohol abuse) were predictors of psychiatric hospitalization in patients with bipolar I disorder (Table 4). In addition, baseline age and lower GAF score were predictors of hospitalization in patients with bipolar II disorder (Table 5). However, the clinical impact of baseline age in patients with bipolar II disorder as a predictor of hospitalization was considered minor because the effect size was very small (p = 0.017, OR = 1.055, 95% CI = 1.010–1.103).

Table 4. Binomial logistic regression analysis of factors for psychiatric hospitalization among patients with bipolar I disorder.

Table 5. Binomial logistic regression analysis of factors for psychiatric hospitalization among patients with bipolar II disorder.

In a real-world Japanese clinical setting, we found that 3.06% of outpatients with bipolar disorder experienced psychiatric hospitalization over the course of the year after baseline. This proportion was lower than observed in previous studies examining predictors of rehospitalization of patients with bipolar disorder (9, 10). Our study participants were likely at relatively low risk of hospitalization because they included patients with no previous hospitalizations. In addition, predictors of psychiatric hospitalization within 1 year in outpatients with bipolar disorder included bipolar I disorder, having a low GAF score, being unemployed, having a co-occurring substance abuse (alcohol abuse), and having a baseline manic state. Of these findings, the most notable came from a comparison of odds ratios; GAF score had the greatest impact on predicting psychiatric hospitalization in patients with bipolar disorder, with lower GAF scores being associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of hospitalization. The combination pattern of prescriptions for mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and antidepressants was not found to be significantly associated with hospitalization of patients with bipolar disorder. The most common prescription pattern was mood stabilizers in combination with antipsychotics, followed by mood stabilizers alone. Therefore, it was considered that overall, pharmacotherapy was practiced in accordance with treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder (1). On the other hand, 2.2% of patients were not using any mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, or antidepressants, but these patients were not hospitalized. Because of the small proportion of patients that were followed up without medication in our study, further research is needed to determine whether patients with stable psychiatric symptoms can be followed up with psychotherapy alone.

We also found that lower baseline GAF scores were significantly associated with the occurrence of psychiatric hospitalization over the course of the year after baseline among outpatients with bipolar disorder. On the other hand, a previous study found that baseline cognitive dysfunction itself is a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with bipolar disorder (25). In addition, other researchers reported that hospitalized patients with bipolar disorder had difficulty improving their social functioning after discharge from the hospital (6). Since there is evidence that treatment for social cognitive dysfunction may improve the quality of life among patients with bipolar disorder by enhancing academic performance, work capacity, and social relationships (26), it is important to implement appropriate evidence-based pharmacotherapy (1) and structured psychotherapy (27) that may improve social functioning from the prehospitalization stage.

In addition, we have shown that bipolar I disorder has a statistically significantly higher risk of hospitalization occurrence than bipolar II disorder over a 1-year observation period. A previously reported large cross-sectional study in Sweden showed that bipolar I disorder was associated with more hospitalizations, lower psychosocial functioning, and lower educational attainment than bipolar II disorder (28). In addition, long-term observational studies have reported more frequent manic/hypomanic episodes in bipolar I disorder than in bipolar II disorder (29, 30). Based on these previous studies, the results of the present study suggest that bipolar I disorder is more likely to present with severe manic and psychosocial dysfunction than bipolar II disorder and is more likely to result in hospitalization.

We have also shown that the baseline manic state of patients with bipolar disorder is a predictor of psychiatric hospitalization over the course of the year after baseline. In bipolar disorder, manic symptoms are reported to be more likely to cause interpersonal problems and are also associated with increased suicide risk (26). In addition, repeated and prolonged manic episodes impair cognitive function (31), and cognitive dysfunction itself has been reported to be a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with bipolar disorder (25). Therefore, treatment strategies focused on manic symptoms and maintenance of remission are needed. For pharmacotherapy of manic symptoms in bipolar disorder, mood stabilizers except lamotrigine are recommended, although concomitant use of antipsychotics may be effective (1). On the other hand, patients with bipolar disorder presenting with manic or psychotic depression reportedly have poor treatment adherence due to decreased insight (32, 33). In particular, patients with comorbid bipolar disorder and substance use disorder have been found to have low rates of adherence in using mood stabilizers (34).

The proportion of substance abuse among bipolar I disorder patients was ~60%, while that of bipolar II disorder was also high at 48% (35). Furthermore, patients with bipolar disorder were found to be over six times more likely than the general population to suffer from substance abuse (35). Patients with comorbid bipolar disorder and substance use disorder are known to have poor treatment adherence, leading to relapses of bipolar disorder (36). Substance use disorders, including alcohol abuse, exacerbate symptoms of bipolar disorder and make it more difficult to treat (36). Therefore, it is critically important for these patients to receive integrated treatment for both diseases, which can improve treatment adherence and outcomes (35).

In the past, there was concern that antidepressant prescriptions for bipolar disorder increased the risk of manic episodes (37). In recent years, however, the combination of mood stabilizers and antidepressants and the prescription of antidepressants for bipolar II disorder have become more acceptable (1). We previously reported that the rate of prescribing antidepressants for patients with bipolar disorder is high in Japan, as in Western countries (14), and that antidepressant prescribing for patients with bipolar disorder was not a predictor of manic/hypomanic episodes during a 1-year observation period (15). This study showed that antidepressant prescriptions at baseline is not a statistically significant predictor of hospitalization among outpatients with bipolar disorder over the course of the year. This result confirmed previous studies on the tolerability of antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder. Interestingly, adjunctive antidepressant therapy has also been shown to decrease the readmission rate of bipolar I depression and prolong the time to readmission during a 1-year observation period (38). A recent review also presented psychosocial therapies for the adjunctive treatment of bipolar disorder that led to increased medication adherence, improved manic symptoms, and improved GAF scores (39). However, prescribing antidepressants to patients with bipolar disorder is not entirely problematic, since the evaluation of antidepressants varies depending on the type of antidepressant and the subtype of bipolar disorder, and the risk of mania is still controversial. Therefore, it might be suggested that the concomitant use of appropriate psychosocial therapies, in addition to pharmacotherapy with attention to adverse events, can lead to improvements in affective symptoms and GAF scores as well as a reduction in the risk of psychiatric hospitalization.

The results of the current study also revealed that comorbid substance use disorders may be a predictor of hospitalization in patients with bipolar disorder. Prior research has reported that substance use disorders, such as alcohol abuse, increase the risk of developing bipolar disorder (40). Substance abuse is also known to be an important risk factor for poor treatment adherence in patients with bipolar disorder (32). Approximately 60% of patients with bipolar disorder are considered at least partially non-adherent to medications (41), and because discontinuation of mood stabilizers increases the risk of relapse, treatment strategies focused on improving adherence have attracted attention (41). Furthermore, not only are substance use disorders frequently comorbid with bipolar disorder, but it has already been reported that comorbid substance use disorders are a poor functional prognostic factor for bipolar disorder (42). In addition, substance use disorders are more common in bipolar I disorder than in bipolar II disorder (43), and patients with bipolar I disorder and substance use disorders have a more severe course (42). The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) has also indicated that baseline substance use disorder is a predictor of manic episodes (44). Since the results of our study revealed that baseline manic state, substance use disorder, and bipolar I disorder are predictors of psychiatric hospitalization, we suggest that outpatient treatment focused on substance use disorder can improve psychiatric symptoms and social functioning and consequently prevent hospitalization.

One mechanism for the development of substance use disorders arises from the self-treatment hypothesis, in which patients begin to use psychoactive substances in a self-medicated manner to heal intolerable psychological distress (45). It has been proposed that when individuals begin to use psychoactive substances such as alcohol in response to psychosocial problems caused by manic and depressive emotional fluctuations in the hope of reducing anxiety and getting better sleep, a dependence is gradually formed, and substance use itself exacerbates psychiatric symptoms (45). Since social isolation is said to be behind substance use disorders (46), group psychotherapy, such as participation in self-help groups, as well as pharmacotherapy may be effective (46). It has been thought that pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy focusing on such substance use disorders could ultimately prevent exacerbations of bipolar disorder.

In addition, this study found that being unemployed was a predictor of hospitalization. This result suggests that social isolation may lead to the exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms. It has also been reported that the intensity of stigma and workplace exclusion for bipolar disorder is associated with unemployment (47). Therefore, we have thought that efforts to improve the work environment and provide support for the patients themselves would lead to an alleviation of their psychiatric symptoms. On the other hand, it is also possible that the patients lost their jobs because they were unable to continue working when social functioning deteriorated due to exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms. Although it is difficult to argue a causal relationship in this regard, further research is needed.

Our study has several limitations. The study was conducted only in clinics that belonged to the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics and consented to participate in the study, which may have population biased the composition of the participants. In addition, patient selection was not randomized and was a retrospective study, which may have led to selection bias in the participating population. In addition, our study found that manic state is an important predictor of hospitalization in patients with bipolar disorder, but we did not analyze the severity of manic state. Furthermore, previous hospitalizations and the number of hospitalizations were not tabulated, making it impossible to separate the risk of first-time hospitalization from the risk of rehospitalization. We also assumed alcohol to be the primary substance of interest for substance use disorders and did not distinguish it from other psych-dependent substances (e.g., cocaine, marijuana, methamphetamine).

Our study showed that five independent variables (low GAF score, bipolar I disorder, baseline manic/hypomanic state, unemployment, and substance use disorder) were predictors of psychiatric hospitalization in patients with bipolar disorder during a 1-year observation period. Previous studies have suggested an association between these independent variables, but our study design did not allow us to go as far as demonstrating a causal relationship.

Our study revealed that 3.06% of outpatients with bipolar disorder experienced psychiatric hospitalization over the course of 1 year from baseline. Our study suggests that a low GAF score, bipolar I disorder, unemployment, comorbid substance use disorder (alcohol abuse), and baseline manic/hypomanic state could be predictors of psychiatric hospitalization.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics and Dokkyo Medical University School of Medicine. Written informed consent from the participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

KT, NY-F, and KW conceived the ideas. NA, YK, YW, KM, TA, KE, EK, SH, EG, and HU collected the data. KT, NY-F, MK, RY, AN, TK, TT, KS, and KW analyzed the data. KT wrote the original draft of the manuscript. NY-F and KS provided critical feedback. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was supported by a Ken Tanaka memorial research grant (Grant Numbers: 2016–2, 2017–4, and 2019–3). The funder had no role in the study design, the data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

The authors thank the following psychiatrists belonging to the Japanese Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Clinics: Dr. Kazunori Otaka, Dr. Satoshi Terada, Dr. Tadashi Ito, Dr. Munehide Tani, Dr. Atsushi Satomura, Dr. Hiroshi Sato, Dr. Hideki Nakano, Dr. Yoichi Nakaniwa, Dr. Eiichi Hirayama, Dr. Keiichi Kobatake, Dr. Koji Tanaka, Dr. Mariko Watanabe, Dr. Shiguyuki Uehata, Dr. Asana Yuki, Dr. Nobuko Akagaki, Dr. Michie Sakano, Dr. Akira Matsukubo, Dr. Yukihisa Kibota, Dr. Yasuyuki Inada, Dr. Hiroshi Oyu, Dr. Tsuneo Tsubaki, Dr. Tatsuji Tamura, Dr. Shigeki Akiu, Dr. Atsuhiro Kikuchi, Dr. Keiji Sato, Dr. Toshihiko Lee, Dr. Kazuyuki Fujita, Dr. Fumio Handa, Dr. Hiroyuki Karasawa, Dr. Kazuhiro Nakano, Dr. Kazuhiro Omori, Dr. Seiji Tagawa, Dr. Daisuke Maruno, Dr. Hiroaki Furui, Dr. You Suzuki, Dr. Takeshi Fujita, Dr. Yukimitsu Hoshino, Dr. Kikuko Ota, Dr. Akira Itami, Dr. Kenichi Goto, Dr. Norio Okamoto, Dr. Yoshiaki Yamano, Dr. Kiichiro Koshimune, Dr. Junko Matsushita, Dr. Takatsugu Nakayama, Dr. Kazuyoshi Takamuki, Dr. Nobumichi Sakamoto, Dr. Miho Shimizu, Dr. Muneo Shimura, Dr. Norio Kawase, Dr. Ryouhei Takeda, Dr. Takuya Hirota, Dr. Hideko Fujii, Dr. Riichiro Narabayashi, Dr. Yutaka Fujiwara, Dr. Junkou Sato, Dr. Kazu Kobayashi, Dr. Yuko Urabe, Dr. Miyako Oguru, Dr. Osamu Miura, Dr. Yoshio Ikeda, Dr. Hidemi Sakamoto, Dr. Yosuke Yonezawa, Dr. Makoto Nakamura, Dr. Yoichi Takei, Dr. Toshimasa Sakane, Dr. Kiyoshi Oka, Dr. Kyoko Tsuda, Dr. Yasushi Furuta, Dr. Yoshio Miyauchi, Dr. Keizo Hara, Dr. Misako Sakamoto, Dr. Shigeki Masumoto, Dr. Yasuhiro Kaneda, Dr. Yoshiko Kanbe, Dr. Masayuki Iwai, Dr. Naohisa Waseda, Dr. Nobuhiko Ota, Dr. Takahiro Hiroe, Dr. Ippei Ishii, Dr. Hideki Koyama, Dr. Terunobu Otani, Dr. Osamu Takatsu, Dr. Takashi Ito, Dr. Norihiro Marui, Dr. Toru Takahashi, Dr. Tetsuro Oomori, Dr. Toshihiko Fukuchi, Dr. Kazumichi Egashira, Dr. Shigemitsu Hayashi, Dr. Kiyoshi Kaminishi, Dr. Ryuichi Iwata, Dr. Satoshi Kawaguchi, Dr. Kazuko Miyauchi, Dr. Yoshinori Morimoto, Dr. Kunihiko Kawamura, Dr. Hirohisa Endo, Dr. Yasuo Imai, Dr. Eri Kohno, Dr. Aki Yamamoto, Dr. Naomi Hasegawa, Dr. Sadamu Toki, Dr. Hideyo Yamada, Dr. Hiroyuki Taguchi, Dr. Hiroshi Yamaguchi, Dr. Hiroki Ishikawa, Dr. Sakura Abe, Dr. Kazuhiro Uenoyama, Dr. Kazunori Koike, Dr. Mikako Oyama, Dr. Yoshiko Kamekawa, Dr. Michihito Matsushima, Dr. Ken Ueki, Dr. Sintaro Watanabe, Dr. Tomohide Igata, Dr. Yoshiaki Higashitani, Dr. Eiichi Kitamura, Dr. Junko Sanada, Dr. Takanobu Sasaki, Dr. Kazuko Eto, Dr. Ichiro Nasu, Dr. Kenichiro Sinkawa, Dr. Yukio Oga, Dr. Michio Tabuchi, Dr. Daisuke Tsujimura, Dr. Tokunai Kataoka, Dr. Kyohei Noda, Dr. Nobuhiko Imato, Dr. Ikuko Nitta, Dr. Yoshihiro Maruta, Dr. Satoshi Seura, Dr. Toru Okumura, Dr. Osamu Kino, Dr. Tomoko Ito, Dr. Ryuichi Iwata, Dr. Wataru Konno, Dr. Toshio Nakahara, Dr. Masao Nakahara, Dr. Hiroshi Yamamura, Dr. Masatoshi Teraoka, EG, Dr. Masato Nishio, Dr. Miwa Mochizuki, Dr. Tsuneo Saitoh, Dr. Tetsuharu Kikuchi, Dr. Chika Higa, Dr. Hiroshi Sasa, Dr. Yuichi Inoue, Dr. Muneyoshi Yamada, Dr. Yoko Fujioka, Dr. Kuniaki Maekubo, Dr. Hiroaki Jitsuiki, Dr. Toshihito Tsutsumi, Dr. Yasumasa Asanobu, Dr. Seiji Inomata, Dr. Kazuhiro Kodama, Dr. Aikihiro Takai, Dr. Asako Sanae, Dr. Shinichiro Sakurai, Dr. Kazuhide Tanaka, Dr. Masahiko Shido, Dr. Haruhisa Ono, Dr. Wataru Miura, Dr. Yukari Horie, Dr. Tetso Tashiro, Dr. Tomohide Mizuno, Dr. Naohiro Fujikawa, Dr. Hiroshi Terada, Dr. Kenji Taki, Dr. Kyoko Kyotani, Dr. Masataka Hatakoshi, Dr. Katsumi Ikeshita, Dr. Keiji Kaneta, Dr. Ritsu Shikiba, Dr. Tsuyoshi Iijima, Dr. Masaru Yoshimura, NA, Dr. Masumi Ito, Dr. Shunsuke Murata, Dr. Mio Mori, and Dr. Toshio Yokouchi.

YK has received consultant fees from Pfizer and Meiji-Seika Pharma and speaker's honoraria from Meiji-Seika Pharma, MSD, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, and Eisai. TA has received speaker's honoraria from Eli Lilly, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, and Eisai. HU has received manuscript fees or speaker's honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Lundbeck Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. KE has received speaker's honoraria from Eli Lilly, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Kyowa, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. EK has received speaker's honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, UCB, and Viatris. SH has received manuscript fees or speaker's honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. EG has received manuscript fees or speaker's honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry, and Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma. MK has received grant funding from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the Japan Society for the Pro- motion of Science, SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation, the Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology and the Japanese Society of Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology and speaker's honoraria from Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Otsuka, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Eli Lilly, MSD K.K., Pfizer, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck and Ono Pharmaceutical and participated in an advisory/review board for Otsuka, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Shionogi and Boehringer Ingelheim. RY has received speaker's honoraria from Eli Lilly, Dainippon Sumitomo, Otsuka, and Esai. AN has received speaker's honoraria from Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Otsuka, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida, Dainippon Sumitomo and NTT Docomo, and participated in an advisory board for Takeda, Meiji Seika, Tsumura and Yoshitomi Yakuhin. TK has received consultant fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical and the Center for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Training. TT has received consultant fees from Pfizer and speaker's honoraria from Eli Lilly, Meiji- Seika Pharma, MSD, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. KW has received manuscript fees or speaker's honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, has received research/grant support from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, MSD, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and is a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Viatris. KS has received research support from Novartis Pharma, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Eisai, Pfizer, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, and Takeda Pharmaceutical and honoraria from Eisai, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer. NY-F has received grant/research support or honoraria from, and received speaker's honoraria of Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, MSD, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2018) 20:97–170. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12609

2. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization (1992).

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publising (2013).

4. McIntyre RS, Berk M, Brietzke E, Goldstein BI, López-Jaramillo C, Kessing LV, et al. Bipolar disorders. Lancet. (2020) 396:1841–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31544-0

5. Carvalho AF, Firth J, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. New Engl J Med. (2020) 383:58–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1906193

6. Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, Cluss PA, Houck PR, Stapf DA. Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals in a bipolar disorder case registry. J Clin Psychiatry. (2002) 63:120–5. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v63n0206

7. López-Villarreal A, Sánchez-Morla EM, Jiménez-López E, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Aparicio AI, Mateo-Sotos J, et al. Predictive factors of functional outcome in patients with bipolar I disorder: a five-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. (2020) 272:249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.140

8. Fornaro M, Iasevoli F, Novello S, Fusco A, Anastasia A, De Berardis D, et al. Predictors of hospitalization length of stay among re-admitted treatment-resistant bipolar disorder inpatients. J Affect Disord. (2018) 228:118–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.009

9. Bozzay ML, Gaudiano BA, Arias S, Epstein-Lubow G, Miller IW, Weinstock LM. Predictors of 30-day rehospitalization in a sample of hospitalized patients with bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 281:112559. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112559

10. O'Hagan M, Cornelius V, Young AH, Taylor D. Predictors of rehospitalization in a naturalistic cohort of patients with bipolar affective disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2017) 32:115–20. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000163

11. Shapiro J, Timmins V, Swampillai B, Scavone A, Collinger K, Boulos C, et al. Correlates of psychiatric hospitalization in a clinical sample of Canadian adolescents with bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. (2014) 55:1855–61. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.08.048

12. Hoblyn JC, Balt SL, Woodard SA, Brooks JO 3rd. Substance use disorders as risk factors for psychiatric hospitalization in bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. (2009) 60:50–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.1.50

13. Ekman M, Granström O, Omérov S, Jacob J, Landén M. The societal cost of bipolar disorder in Sweden. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2013) 48:1601–10. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0724-9

14. Tokumitsu K, Yasui-Furukori N, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Watanabe Y, Miki K, et al. Real-world clinical features of and antidepressant prescribing patterns for outpatients with bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:555. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02967-5

15. Tokumitsu K, Norio YF, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Watanabe Y, Miki K, et al. Real-world clinical predictors of manic/hypomanic episodes among outpatients with bipolar disorder. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0262129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262129

16. Kato M, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, Ueda H, Edagawa K, et al. Clinical features related to rapid cycling and one-year euthymia in bipolar disorder patients: a multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric clinics (MUSUBI). J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 131:228–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.030

17. Sugawara N, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Watanabe Y, Miki K, Azekawa T, et al. Determinants of three-year clinical outcomes in real-world outpatients with bipolar disorder: the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (MUSUBI). J Psychiatr Res. (2022) 151:683–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.05.028

18. Shinozaki M, Yasui-Furukori N, Adachi N, Ueda H, Hongo S, Azekawa T, et al. Differences in prescription patterns between real-world outpatients with bipolar I and II disorders in the MUSUBI survey. Asian J Psychiatr. (2022) 67:102935. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102935

19. Adachi N, Azekawa T, Edagawa K, Goto E, Hongo S, Kato M, et al. Estimated model of psychotropic polypharmacy for bipolar disorder: analysis using patients' and practitioners' parameters in the MUSUBI study. Hum Psychopharmacol. (2021) 36:e2764. doi: 10.1002/hup.2764

20. Yasui-Furukori N, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, Goto E, Edagawa K, et al. Factors associated with doses of mood stabilizers in real-world outpatients with bipolar disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. (2020) 18:599–606. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2020.18.4.599

21. Tsuboi T, Suzuki T, Azekawa T, Adachi N, Ueda H, Edagawa K, et al. Factors associated with non-remission in bipolar disorder: the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (MUSUBI). Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2020) 16:881–90. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S246136

22. Ikenouchi A, Konno Y, Fujino Y, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, et al. Relationship between employment status and unstable periods in outpatients with bipolar disorder: a multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric outpatient clinics (MUSUBI) study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2022) 18:801–9. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S353460

23. Konno Y, Fujino Y, Ikenouchi A, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Azekawa T, et al. Relationship between mood episode and employment status of outpatients with bipolar disorder: retrospective cohort study from the multicenter treatment survey for bipolar disorder in psychiatric clinics (MUSUBI) project. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2021) 17:2867–76. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S322507

24. Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2013) 48:452–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244

25. Lima IMM, Peckham AD, Johnson SL. Cognitive deficits in bipolar disorders: implications for emotion. Clin Psychol Rev. (2018) 59:126–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.006

26. Vieta E, Berk M, Schulze TG, Carvalho AF, Suppes T, Calabrese JR, et al. Bipolar disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2018) 4:18008. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.8

27. Miklowitz DJ, Efthimiou O, Furukawa TA, Scott J, McLaren R, Geddes JR, et al. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. (2021) 78:141–50. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2993

28. Karanti A, Kardell M, Joas E, Runeson B, Pålsson E, Landén M. Characteristics of bipolar I and II disorder: a study of 8766 individuals. Bipolar Disord. (2020) 22:392–400. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12867

29. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2002) 59:530–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530

30. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2003) 60:261–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261

31. Martino DJ, Igoa A, Marengo E, Scápola M, Strejilevich SA. Longitudinal relationship between clinical course and neurocognitive impairments in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. (2018) 225:250–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.011

32. Jónsdóttir H, Opjordsmoen S, Birkenaes AB, Simonsen C, Engh JA, Ringen PA, et al. Predictors of medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2013) 127:23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01911.x

33. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Lack of insight in mood disorders. J Affect Disord. (1998) 49:55–8. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00198-5

34. Manwani SG, Szilagyi KA, Zablotsky B, Hennen J, Griffin ML, Weiss RD. Adherence to pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorder patients with and without co-occurring substance use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. (2007) 68:1172–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0802

35. Salloum IM, Thase ME. Impact of substance abuse on the course and treatment of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2000) 2:269–80. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20308.x

36. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, West SA, Sax KW, Hawkins JM, et al. 12-month outcome of patients with bipolar disorder following hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry. (1998) 155:646–52. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.646

37. Viktorin A, Lichtenstein P, Thase ME, Larsson H, Lundholm C, Magnusson PK, et al. The risk of switch to mania in patients with bipolar disorder during treatment with an antidepressant alone and in combination with a mood stabilizer. Am J Psychiatry. (2014) 171:1067–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111501

38. Shvartzman Y, Krivoy A, Valevski A, Gur S, Weizman A, Hochman E. Adjunctive antidepressants in bipolar depression: a cohort study of six- and twelve-months rehospitalization rates. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2018) 28:353–60. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.01.010

39. Chatterton ML, Stockings E, Berk M, Barendregt JJ, Carter R, Mihalopoulos C. Psychosocial therapies for the adjunctive treatment of bipolar disorder in adults: network meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 210:333–41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.195321

40. Gordon-Smith K, Lewis KJS, Vallejo Auñón FM, Di Florio A, Perry A, Craddock N, et al. Patterns and clinical correlates of lifetime alcohol consumption in women and men with bipolar disorder: findings from the UK bipolar disorder research network. Bipolar Disord. (2020) 22:731–8. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12905

41. Gaudiano BA, Weinstock LM, Miller IW. Improving treatment adherence in bipolar disorder: a review of current psychosocial treatment efficacy and recommendations for future treatment development. Behav Modification. (2008) 32:267–301. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309023

42. Preuss UW, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM. A prospective comparison of bipolar I and II subjects with and without comorbid alcohol dependence from the COGA dataset. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:522228. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.522228

43. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. (1990) 264:2511–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450190043026

44. Niitsu T, Fabbri C, Serretti A. Predictors of switch from depression to mania in bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. (2015) 66–7:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.014

45. Khantzian EJ, Albanese MJ. Understanding Addiction as Self Medication: Finding Hope Behind the Pain. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2008).

46. Volkow ND. Personalizing the treatment of substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:113–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19121284

Keywords: bipolar disorder, predictor, real-world, outpatient, hospitalization

Citation: Tokumitsu K, Yasui-Furukori N, Adachi N, Kubota Y, Watanabe Y, Miki K, Azekawa T, Edagawa K, Katsumoto E, Hongo S, Goto E, Ueda H, Kato M, Nakagawa A, Kikuchi T, Tsuboi T, Watanabe K, Shimoda K and Yoshimura R (2023) Predictors of psychiatric hospitalization among outpatients with bipolar disorder in the real-world clinical setting. Front. Psychiatry 14:1078045. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1078045

Received: 24 October 2022; Accepted: 20 February 2023;

Published: 16 March 2023.

Edited by:

Yuji Ozeki, Shiga University of Medical Science, JapanReviewed by:

Jun-Ichi Iga, Ehime University, JapanCopyright © 2023 Tokumitsu, Yasui-Furukori, Adachi, Kubota, Watanabe, Miki, Azekawa, Edagawa, Katsumoto, Hongo, Goto, Ueda, Kato, Nakagawa, Kikuchi, Tsuboi, Watanabe, Shimoda and Yoshimura. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Norio Yasui-Furukori, ZnVydWtvcmlAZG9ra3lvbWVkLmFjLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.