95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 23 September 2022

Sec. Addictive Disorders

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.992309

This article is part of the Research Topic Gambling, Stigma, Suicidality, and the Internalization of the ‘Responsible Gambling’ Mantra View all 6 articles

Ludwig Kraus1,2,3*

Ludwig Kraus1,2,3* Johanna K. Loy2

Johanna K. Loy2 Andreas M. Bickl2

Andreas M. Bickl2 Larissa Schwarzkopf2

Larissa Schwarzkopf2 Rachel A. Volberg4

Rachel A. Volberg4 Sara Rolando5

Sara Rolando5 Veera E. Kankainen6

Veera E. Kankainen6 Matilda Hellman6

Matilda Hellman6 Ingeborg Rossow7

Ingeborg Rossow7 Robin Room1,8

Robin Room1,8 Thomas Norman8,9

Thomas Norman8,9 Jenny Cisneros Örnberg1

Jenny Cisneros Örnberg1While there is evidence for self-exclusion (SE) as an individual-level harm reduction intervention, its effects on reducing harm from gambling at the population level remain unclear. Based on a review of national legal frameworks and SE programs, including their utilization and enforcement in selected high-income societies, the present analysis aims to explore the reach and strengths of SE in the protection of gamblers in these jurisdictions. It places particular emphasis on SE programs' potential to prevent and minimize gambling harm at the population level. The overview examined SE in Finland, Germany, Italy, Massachusetts (USA), Norway, Sweden, and Victoria (Australia). These jurisdictions differ considerably in how gambling is regulated as well as in how SE is implemented and enforced. The reach and extent of enforcement of SE apparently vary with the polity's general policy balance between reducing gambling problems and increasing gambling revenue. But in any case, though SE may benefit individual gamblers and those around them, it does not appear to be capable of significantly reducing gambling harm at the population level. To render SE programs an effective measure that prevents gamblers and those linked to them from financial, social, and psychological harm, utilization needs to be substantially increased by reforming legal regulations and exclusion conditions.

Land-based gambling and more recently online gambling have increased in many parts of the world partly as the result of increasing liberalization and deregulation of gambling. Especially online gambling, previously illegal in most countries, has been legalized within existing schemes or by issuing licenses to national providers, resulting in an only partly regulated online market (1). The Gross Gambling Revenue, defined as the sum of all money gambled minus the wins returned to gamblers, is estimated to have almost doubled in Europe between 2003 and 2018, with an increase from 56 to over 100 billion EUR (2). In parallel, the revenues gained by states via a monopolistic position or by taxing licensed gambling provide reliable resources to fund welfare programs and other public expenses (3). For instance, about 60% of support for the cultural sector and 80% of support for sports activities in Finland stem from gambling-generated revenues (2). In Australia, revenue from gambling taxes is estimated to account for 8.4% of the Victorian state tax revenue (4). However, along with the substantial growth of the gambling market, concerns about harms from gambling emerge, along with calls for measures to keep a balance between the societal benefits, the spread of fraud and crime, and the harms associated with gambling (5–7).

Several measures that may help in reducing harm to the gambler have been discussed within the framework of “responsible gambling” (RG). This conceptualization is used by the industry to handle the two sides of the coin: gambling as a fun activity and the risk of harm from gambling (8, 9). RG measures put forward to limit harm from gambling include, amongst others, protective behavioral strategies such as self-exclusion, time and monetary limit setting, or card-based gambling programs, that allow individuals to load a predetermined amount of money onto a card (10). In contrast, the public health approach aims at reducing supply, for instance by removing gambling machines or reducing operating hours (2, 11). Although there is sound evidence for the impact of supply reduction measures on the prevalence of gambling and gambling harm (12–14), the revenue of the commercial gambling industry, as well as the maintenance of taxation revenue by governments, are two strong interests that are diametrically opposed to the goal of reducing harm by reducing supply (15). As supply reduction measures jeopardize the expansion of the gambling industry and reduce governmental funds for public services, individual-level measures targeting the gambler have become more politically popular. From the perspective of the gambling industry, such measures have the added benefit of diverting policy attention from the industry's promotion and incentives by pointing to deficiencies in the individual gambler. One set of such measures is the widely adopted self-exclusion (SE) measure, which offers gamblers a choice to ban themselves from particular gambling venues or from land-based as well as online gambling. SE from gambling is primarily an individualized harm reduction measure that aims at preventing gamblers from further financial, social, and psychological distress (16, 17).

Commercial casinos and gambling companies frequently offer SE, permitting individuals to ban themselves from entering specific venues or using specific services. More recently, several SE programs have evolved toward an individual assistance model where enrolees are offered not only debt counseling but also psychological support and addiction treatment (18–21).

By SE programs and provisions, we are here referring to regulations or a gambling provider's rule that allows a gambler to request not being permitted to engage in gambling with a specified provider or category of providers. Usually, a written and signed application is required, and the provider undertakes to refuse any attempt by the self-excluder to gamble with the provider for the period specified in the application. Thus, the provider's staff is expected to refuse entry to a gambling site or platform if the self-excluder is identified in or while seeking entry to the site or platform. In some jurisdictions, the SE program is legislated or otherwise officially sanctioned with penalties for non-compliance by a gambling provider. But while there is growing evidence of SE programs having the potential to be an effective individual-level harm reduction intervention (10, 22–24), their effects on reducing harm from gambling at the population level are questionable (25).

Considering the substantial differences in how jurisdictions regulate gambling and implement control measures, the present study aims to analyze and compare the approach, implementation, and scope of legal frameworks and SE programs in a purposive selection of high-income countries or states. Secondly, we pay special attention to SE in the framework of “responsible gambling” to address gambling harm: whether and under what conditions SE may have an effect on problem gambling in the population as a whole. The countries/states that were chosen for this overview are Finland, Germany, Italy, Massachusetts (USA), Norway, Sweden, and Victoria (Australia), representing a broad spectrum of regulatory policies and implementation of SE regulations. In each of the seven jurisdictions available information on legal frameworks of gambling and SE regulations, including registers, length and termination, utilization and enforcement was collected by a team which is a partner of the project “Responding to and Reducing Gambling Problems Studies (REGAPS).”

The information on frameworks for gambling regulation is summarized by country/state in Table 1. Gambling in the legal context is defined as placing something of value at risk in the hopes of gaining something of greater value (26). While Finland and Norway maintain a state monopoly (or another strongly regulated monopoly) on all or some forms of gambling, in Italy, Massachusetts, and Victoria gambling is fully or partially licensed to commercial providers. In Germany and Sweden, a state monopoly and a licensing system exist in parallel.

State monopolies, however, are not without exceptions. In Norway, for instance, private lotteries and bingos provide a particular form of gambling in addition to two monopoly providers (Norsk Tipping and Norsk Rikstoto). The German gambling monopoly includes casinos, lotteries, sports betting, and electronic gambling machines (EGMs) but excludes commercial amusement machines with prizes (AWP), which are offered by private enterprises. With the 4th revision of the German State Treaty on Gambling that came into force in July 2021, online gambling, including online sports betting, has been widely legalized and opened for commercial providers within a licensing system. Similarly, online gambling in Sweden is also subject to licensing. The new license system went into force on January 1, 2019 in the context of the Swedish Gambling Act of 2018 giving Sweden a new re-regulated gambling market. The non-competitive forms are monopolized by the state or licensed to non-profit “good cause” organizations. Forms of gambling that are subject to competition are online gambling and land-based games such as card games.

In Italy, the gambling market is based on concessions, a type of license that allows the holder to act as a proxy for the state while exonerating it from responsibility for negative externalities caused by the activity (27). This includes all types of games as well as EGMs that are also placed in general venues such as tobacco shops and bars. Concessions are granted through public tenders. In Victoria and Massachusetts gambling is formally license-based. In Victoria, casino games are offered within the scope of a private monopoly that is issued by the state to Crown Melbourne. EGMs are licensed not only in the casino but also in taverns (“hotels”) and sports and community clubs. In Massachusetts, licenses apply to casinos, racing, bingo, and charitable events, while the state maintains its monopoly on lotteries.

The main differences in gambling regulations in these countries/states consist in the scope of monopolization of gambling, the extent of the market that is shared with or entrusted to private providers via licenses or concessions, the modalities of online gambling provision, and the share of the online market that is not monopolized or licensed. In the late 1990s, in the context of the growing internet gambling market, the European Union (EU) repeatedly questioned member states' monopolies and their compatibility with European Community law (28). The private gambling industry's demand for deregulation and access to markets regulated by national monopolies was strengthened by the argument for free movement of goods and services in the European internal market and similar global trends (29). As member states had justified their gambling monopolies by their ability to provide revenues for the public good in the form of charities, grants, or taxes, and by preventing fraud, money laundering, and black-market gambling, the European Commission argued that using gambling revenue for the common good cannot be the reason for a monopoly. It furthermore required proof from the monopoly providers that the stated objective to prevent gambling problems was genuine (28).

Subsequently, member states emphasized the prevention of societal and individual problems as an important justification for maintaining the gambling monopoly but had to find means to allow access to internet gambling providers. Countries had to develop strategies suited to supporting the line of argumentation that a (partially) regulated online gambling market could curb the previous black market and steer online gambling into controllable channels. Consequently, in Finland, Norway, and Sweden (until 2019), the increased focus on gambling-related problems and emphasis on the responsible nature of monopoly-based systems to tackle these problems made it possible to keep the monopoly and even expand its activities to the Internet (1, 30). Recently, Germany opened the sports betting market for commercial providers and now accepts online provisions of sports and horse betting, casino games, virtual gambling machines and poker (31). Other countries like Italy adapted their regulations for foreign online operators to apply for gambling licenses. Operators do not have to be government-owned or conduct their business through a company registered in Italy (27). Online gambling in Victoria is licensed while in Massachusetts it is illegal.

It remains unclear how effectively the different regulatory regimes contribute to reducing gambling-related harm. According to a recent literature review, monopolistic regimes apparently perform somewhat better than license-based regimes in preventing problem gambling and limiting gambling in general (32). Because of the significant differences across the included monopolistic systems, the authors argued that other factors such as “availability, accessibility, scope of preventive work, responsible gambling policies, the existence of a sufficiently resourced independent monitoring body, as well as the implementation of a public health approach to gambling may better predict the levels of harm in society” than a monopoly (32) (p.232). It also tends to matter where the monopoly is located in the governmental structure—for instance, in the jurisdiction of the finance department or of a health or welfare department. These findings are in accordance with historical experience with state monopolies of markets for other attractive but problematic commodities—such as psychoactive substances (33).

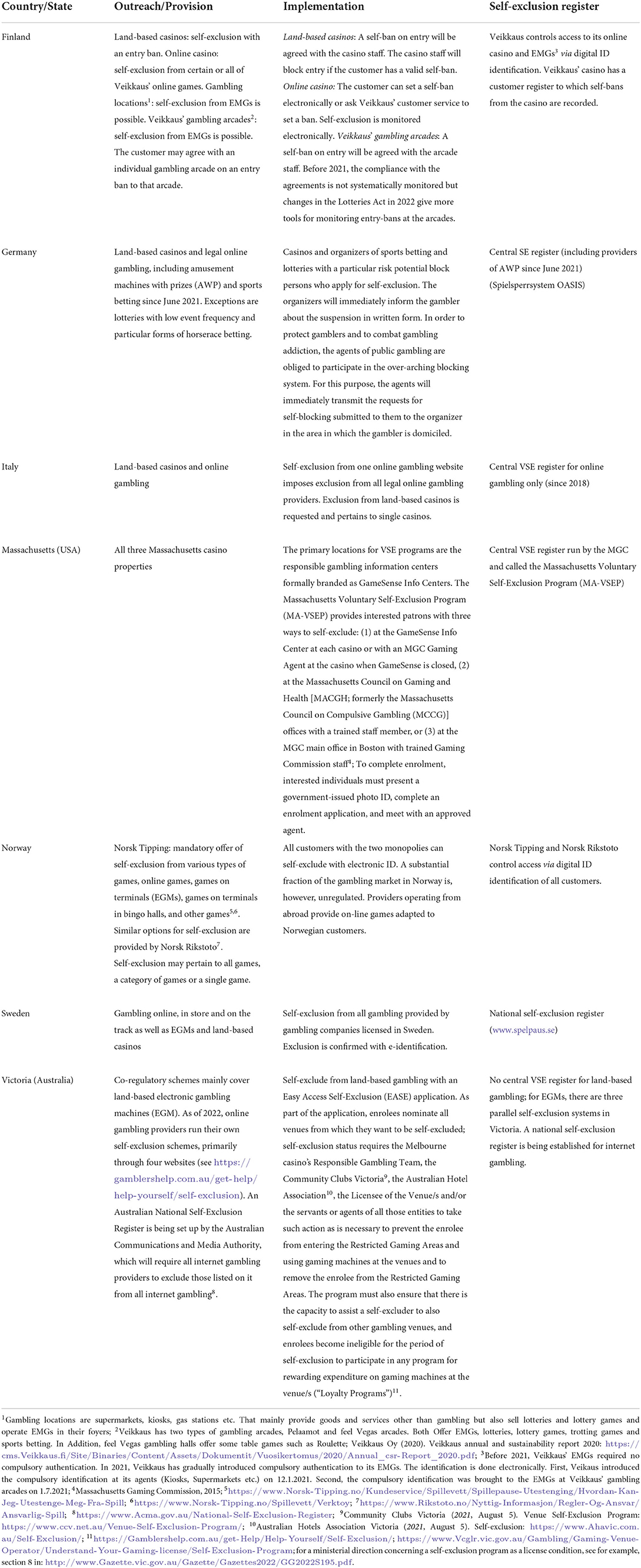

An overview of SE regulations including provision and implementation, the existence of a central register, the individual choices of temporary and permanent bans, and the scope of utilization and control for the seven jurisdictions is provided in Table 2. In all jurisdictions, customers can self-exclude from online or land-based casino games and EGMs or both. Lotteries are generally excluded from SE provision. The reach of SE by interested gamblers differs between jurisdictions by type of game and whether they are offered online or land-based or both. However, while land-based provision of gambling is regulated in all jurisdictions by a state monopoly or a license/concession system, SE for online gambling only applies to providers that hold a license in the respective jurisdiction. Hence, the—generally unrecorded—fraction of total online gambling that is unregulated (unlicensed online games offered from abroad) needs to be considered. For example, in Norway, unrecorded provision is estimated at about one-third of all gambling (34).

Table 2. Summary of voluntary self-exclusion regulations (outreach/provision, implementation, central register) by country/state.

Germany, Italy, Massachusetts, Norway, and Sweden maintain a central nation-/state-wide SE register, which enables an ID-based identification of self-excluded gamblers. These consumers ought to be denied access when trying to gamble at any venue or online service covered by the register. The Norwegian register covers all land-based gambling, the German and Swedish registers also include all licensed online services. The Italian national register covers self-exclusion from all online gambling providers holding a concession, while self-exclusion from land-based gambling is established separately for each casino; hence identification of self-excluded gamblers across sites is limited. This is also true for Finland, where customers can self-exclude from all online gambling via ID identification. If a customer, however, wants to self-exclude from the land-based gambling sites, (s)he needs to ask for an entry ban from the staff at each individual gambling site. In Massachusetts, the register applies to all three land-based casino properties. Victoria provides no central SE register; there are three separate systems operated on a co-regulatory basis by the casino, by the association of community and sports clubs, and by the hotels (taverns) association. For internet gambling, the Australian government is currently setting up a national SE register which will apply to all forms of online gambling.

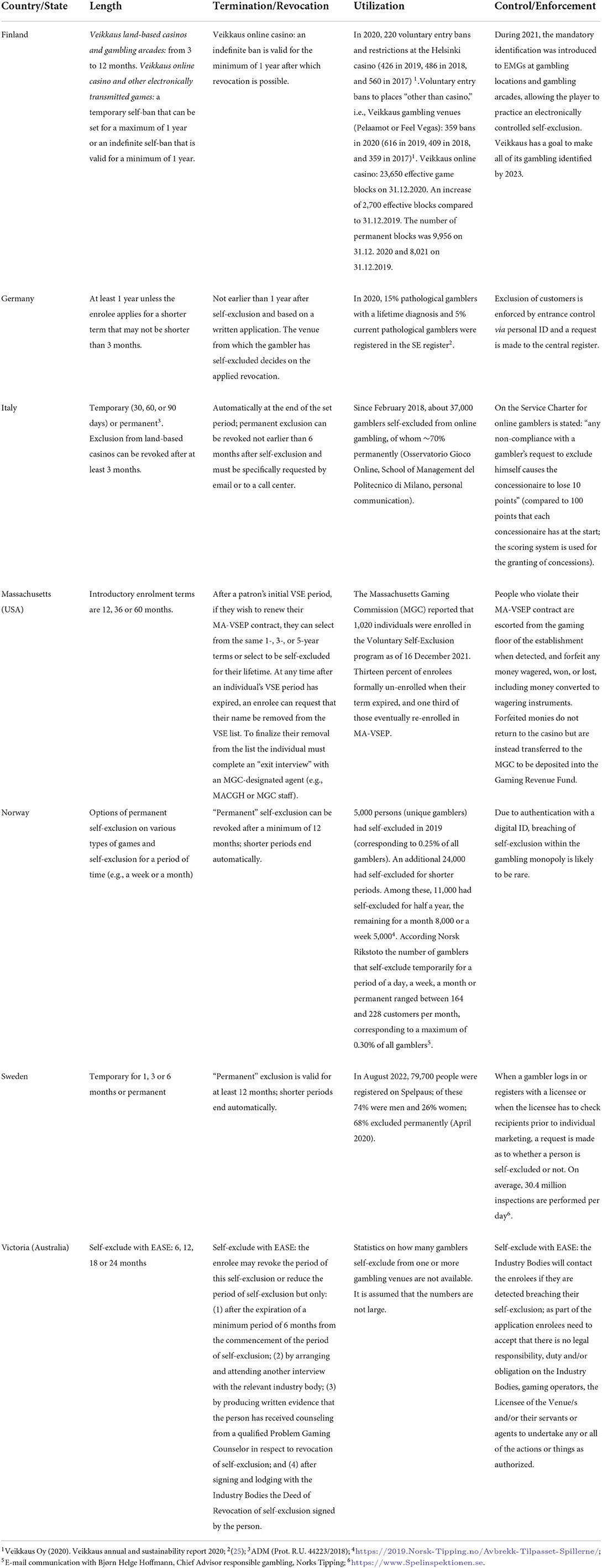

Options for the length of exclusion are manifold and vary across countries/states. In Finland, Italy, Norway and Sweden, customers can choose between various time periods and so-called “permanent” exclusion as it can be revoked after a certain period (Table 3). In Germany, SE lasts at least 1 year unless the enrolee applies for a shorter term, which must have a minimum length of 3 months. In Victoria, enrolment terms are 6, 12, 18 or 24 months, and in Massachusetts 12, 36 or 60 months. Temporal self-exclusion terminates automatically at the end of the set period in Finland, Italy, and Sweden. “Permanent” bans in Finland and Sweden are valid for a minimum of 1 year, and in Italy for 6 months; thereafter removal can be requested. In Finland, these bans will be lifted 3 months after the request for removal. In Massachusetts, enrolees must complete an “exit interview” from the SE program with a Massachusetts Gaming Commission-designated agent. In Italy and Germany, revocation of any SE requires a written application, and in Victoria, an enrolee must attend an interview with the relevant Industry body and produce written evidence that (s)he has received counseling from a qualified Problem Gambling Counselor.

Table 3. Summary of voluntary self-exclusion regulations (length, termination/revocation, utilization, control/enforcement by country/state.

As gamblers can choose to engage in SE or not, its effectiveness in reducing harm mainly hinges on the individual gambler's motivation. The responsible gambling paradigm binds all gambling providers (governmental and licensed) to take responsible steps to prevent and minimize harm from gambling (28). Based on the assumption that problem gamblers are the ones that need to be protected from excessive gambling, SE could serve as an indicator of successful interventions (25). For Germany, the author estimated that 15 out of 100 individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of gambling disorder and 5 out of 100 individuals with a current gambling disorder self-excluded from gambling. Only Norway provides exact figures in relation to the total number of gamblers. In 2019, 29,000 persons had self-excluded from gambling, corresponding to 1.45% of the registered gamblers at Norsk Tipping. Including those who self-excluded at Norsk Rikstoto (0.3%) the proportion of gamblers who self-excluded amounted to 1.75%. For the other jurisdictions, only absolute numbers are reported, although no figures are reported for Victoria (Table 3).

Self-exclusion can only be enforced routinely and completely if IDs of customers entering venues or logging on to gambling websites are checked against entries in a nation- or state-wide self-exclusion register. Such procedures have been implemented for land-based gambling in Massachusetts and Norway, for both online and land-based gambling in Sweden and most recently in Germany, and only for online gambling in Italy. Identification checks in Finland that were mandatory for Veikkaus online and land-based casinos have recently also been made mandatory when gambling at Veikkaus arcades and gambling locations. In Victoria, the industry self-regulatory office ought to theoretically contact the self-excluded gamblers if they are detected breaching their ban, but providers in parallel SE consortia are not liable for access checks. Indeed, enrolees must accept that there is no legal responsibility, duty and/or obligation on the industry bodies, gaming operators, the licensee of the venue/s and/or their servants or agents to undertake any actions that are authorized by the application as part of the application process. Customer penalties for violating SE are reported in Massachusetts. Enrolees violating their voluntary SE contract are escorted from the gaming floor of the establishment when detected and forfeit any money wagered, won, or lost, including money converted to wagering instruments. Forfeited monies are transferred to the Massachusetts Gaming Commission to be deposited into the Gaming Revenue Fund. In Sweden, the Gambling Authority has been reported to impose extensive fines on the gambling industry for violating the law regarding self-exclusion (Table 3).

The seven jurisdictions included in this overview differ considerably in how gambling is regulated as well as in how SE is implemented and enforced. The reach and strength of the system, i.e., the extent to which there is actual enforcement of gambling providers' implementation of the system and the extent that they actually exclude, seem to vary with the polity's general policy balance between reducing gambling problems and increasing gambling revenue and building the economy. In Norway and Sweden, and to some extent also in Finland, with a strong focus on perceiving gambling as a public health and welfare issue, gambling—including the most addictive games—is strongly regulated through a state monopoly or licensing system where all gamblers are offered SE. With electronic ID for gambling, along with several other measures, SE appears to be better enforced than in Italy, Germany, Massachusetts, and Victoria.

Self-exclusion systems seem to be weak and thinly “patronized” in polities that have valued the revenue goal over the harm limitation goal. For instance, there have been considerable political scandals over gambling in Victoria, including money laundering and the laxness of state regulators, which resulted in a recent investigation into Crown Melbourne's business practices by a Victorian Royal Commission. In its report, the Commission concluded that “Crown Melbourne has for many years consistently breached its Gambling Code and, therefore, a condition of its casino licence” (35) (Volume 3, p. 37) because it failed to adequately interact with problem gamblers. Placing Victoria at one end and Norway and Sweden at the other end of the continuum of restrictive gambling policies appears to largely correspond with figures for gross gambling revenue per adult resident, with >900€ per head for Australia and < 400€ for Norway (2). Nevertheless, even in countries/states with strong gambling policies, a large part of the online gambling market is still not monopolized or licensed. The effectiveness of SE programs is limited by the possibility for customers to breach SE, for instance, by switching from licensed to unlicensed providers and often also by the lack of strict enforcement compelling the industry to follow SE regulations.

The gambling and SE regulations in all jurisdictions described above reveal several weaknesses that make SE ineffective in significantly reducing rates of gambling harm at the population level. First, in all jurisdictions, a substantial part of the gambling market is not monopolized or licensed. Self-excluded customers may continue to gamble at online providers that are not covered by the monopoly or that operate without a license in the particular jurisdiction. Second, with few exceptions there is a lack of consistent enforcement of the implementation of coherent SE regulations by both the state and the industry. Third, incoherent SE registers—if implemented at all—enable gamblers to circumvent the ban by, for instance, switching providers or changing from land-based to online formats, and vice versa; in fact, customers' breach of agreement seems to be the rule rather than the exception (10, 36). In a study by Nelson et al. (37), which surveyed gamblers under a lifetime exclusion agreement over an average period of 6.1 years, only 13% had not gambled at all since enrolment. A recent German study reported that 28.1% of gamblers were able to gamble on EGMs despite their SE (38). Presently, only Germany's, Norway's, and Sweden's SE systems and registers cover both land-based and licensed online gambling. The coverage of SE registers of the gambling market in the other countries/states is either low or a central register is not implemented at all. Fourth although data on this is not routinely available in any of the jurisdictions, the existing evidence points to a low rate of excluded problem gamblers. As problem gamblers are the target of SE measures, the effects on reducing gambling harm at the population level presumably remain low as long as the share of excluded problem gamblers among the total of problem gamblers is low. Fifth although studies investigating satisfaction with SE strategies reported generally positive ratings by the majority of respondents (39, 40), the decision to self-exclude or not is an individual choice. Hence, the effectiveness of SE in reducing harm at the population level mainly hinges on the individual gambler's motivation.

Responsible gambling measures to prevent and minimize gambling harm, including but not limited to SE, have frequently been criticized as ineffective (41) and ethically problematic (3, 7). Rather than continuously extending gambling provisions, these authors propose limiting or eliminating certain forms of gambling-related harm. As measures which limit gambling conflict with the economic interests of both governmental and commercial gambling providers, their willingness to exercise strict regulation and enforcement is poor. This dilemma has been identified as the fundamental paradox in the gambling risk management agenda (42).

The option of gamblers banning themselves from gambling temporarily or permanently is inherently an “RG” measure in several senses of the term. First, it defines problematic gambling in terms of a dichotomy between a self-controlled course of action and behavior that is beyond the actor's self-control—why else would the gambler need to self-exclude? Second, it points to the gambler and the gambler's self-control as the aspect of the gambling transaction that is responsible for any problems—promotions and attractions from the gambling provider are out of the picture. Third, it offers an alibi to the provider and the gambling industry when harms occur—“look at what we are offering to avoid such situations.” Fourth, it is a measure that has proven to have only limited costs to the industry, in terms of how many gamblers take up the offer. This advantage is taken to a somewhat cynical length in Victoria, with the provision excluding possible payment of any damages by the gambling provider if the self-excluded person gambles anyway and loses again. Finally, SE is a rather peculiar strategy for limiting harm that has spread widely but is unique to gambling. There is no other attractive but problematic commodity or behavior to which an SE strategy has been applied as a major harm prevention strategy. In sum, by shifting the responsibility to the gambler, the state violates its responsibility to protect gamblers from gambling-related harm. This is particularly the case as about 60% of gambling revenue is estimated to come from problem gamblers (25, 43).

In the included jurisdictions SE, as implemented, is a measure with only weak effects on public health. It is presumably the problem gamblers who need to be excluded, and although they are few, they account for a fairly large fraction of total gambling revenue. If a substantial proportion of the problem gamblers were excluded, it would have a significant impact on reducing gambling harm. In order to become an effective measure that protects those who are at risk for gambling problems and need to be prevented from financial, social, and psychological distress, SE utilization would need to be substantially increased by reforming legal regulations and exclusion conditions. This includes, among others, the closing of loopholes, i.e., minimizing the unlicensed part of the market; strict monitoring of providers' compliance with gambler protection regulations and early recognition activities by an independent body of control; a coherent SE register, including online and land-based gambling with ID checks of individuals at any time when initiating gambling. In addition, information for and motivation of gamblers, their relatives and gambling providers need to be intensified. Most importantly, the proportion of self-excluded problem gamblers among the total of problem gamblers needs to be established as a public health measure of effectiveness. An all-encompassing, well-functioning self-exclusion system could then be a part of a public health approach to effectively reducing gambling harm.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

LK, JKL, AMB, and LS designed the study. LK wrote the initial draft of the paper. RAV, SR, VEK, MH, IR, RR, TN, and JCÖ contributed by providing documents. All authors gave important feedback in revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

This study was conducted within the framework of the Swedish program grant Responding to and Reducing Gambling Problems—Studies in Help-seeking, Measurement, Comorbidity and Policy Impacts (REGAPS) and the Bavarian Coordination Center for Gambling Issues [Landesstelle Glücksspielsucht Bayern (LSG)]. REGAPS received funding from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forte; grant number 2016-07091). The LSG was funded by the Bavarian State Ministry of Public Health and Care Services. The State of Bavaria provides gambling services (lotteries, sports betting, and casino games) within the State gambling monopoly via the State Lottery Administration and provided funding for the Bavarian Coordination Center for Gambling Issues as an unrestricted grant. JCÖ, LK, SR, RAV, RR, and TN were supported by the Forte grant and LK, JKL, AMB, and LS by the Bavarian State Ministry of Public Health and Care Services. Funding for VEK and MH stems from a cooperation contract with the National Institute for Health and Welfare. The money is originally debited from the gambling monopoly retrospectively by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health according to section 52 in the Lotteries Act; IR was supported by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Cisneros Örnberg J, Tammi T. Gambling problems as a political framing-safeguarding the monopolies in Finland and Sweden. J Gambl Issues. (2011) 26:110–25. doi: 10.4309/jgi.2011.26.8

2. Sulkunen P, Babor TF, Cisneros Ornberg J, Egerer M, Hellman M, Livingstone C, et al. Setting Limits: Gambling, Science and Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online (2019). doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198817321.001.0001

4. Livingstone C,. Crown Resorts is Not Too Big to Fail. It has Failed Already. (2021). Available online at: https://theconversation.com/crown-resorts-is-not-too-big-to-fail-it-has-failed-already-165659#:~:text=In%202018-19%20Crown%27s%20last,8.4%25%20of%20state%20tax%20revenue (accessed August 9, 2021).

5. Egerer MD, Kankainen V, Hellman M. Compromising the public good? Civil society as beneficiary of gambling revenue. J Civ Soc. (2018) 14:207–21. doi: 10.1080/17448689.2018.1496306

6. Productivity Commission,. Gambling. Productivity Commission Report No. 50, 26 February. 2 volumes. Commonwealth of Australia (2010). Available online at: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/gambling-2010 (accessed July 1, 2022).

7. Kankainen V, Lerkkanen T, Hellman M. Mundane constructs of the third and public sectors in the Finnish welfare state. Nordisk välfärdsforskning|Nordic Welf Res. (2021) 6:180–91. doi: 10.18261/issn.2464-4161-2021-03-05

8. Blaszczynski A, Ladouceur R, Shaffer HJ. A science-based framework for responsible gambling: the Reno model. J Gambl Stud. (2004) 20:301–17. doi: 10.1023/B:JOGS.0000040281.49444.e2

9. Blaszczynski A, Collins P, Fong D, Ladouceur R, Nower L, Shaffer HJ, et al. Responsible gambling: general principles and minimal requirements. J Gambl Stud. (2011) 27:565–73. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9214-0

10. Drawson AS, Tanner J, Mushquash CJ, Mushquash AR, Mazmanian D. The use of protective behavioral strategies in gambling: a systematic review. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2017) 15:1302–19. doi: 10.1007/s11469-017-9754-y

11. van Schalkwyk MC, Petticrew M, Cassidy R, Adams P, McKee M, Reynolds J, et al. A public health approach to gambling regulation: countering powerful influences. Lancet Public Health. (2021) 6:e614–9. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00098-0

12. Meyer G, Kalke J, Hayer T. The impact of supply reduction on the prevalence of gambling participation and disordered gambling behavior: a systematic review. Sucht. (2018) 64:295–306. doi: 10.1024/0939-5911/a000562

13. Rossow I, Hansen MB. Gambling and gambling policy in Norway—an exceptional case. Addiction. (2016) 111:593–8. doi: 10.1111/add.13172

14. Rolando S, Scavarda A, Devietti Goggia F, Spagnolo M, Beccaria F. Italian gamblers' perspectives on the impact of slot machine restrictions on their behaviors. Int Gambl Stud. (2021) 21:346–59. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2021.1885724

15. Blaszczynski A. Responsible gambling: the need for collaborative government, industry, community and consumer involvement. Sucht. (2018) 64:307–15. doi: 10.1024/0939-5911/a000564

16. Korn DA, Shaffer HJ. Gambling and the health of the public: adopting a public health perspective. J Gambl Stud. (1999) 15:289–365. doi: 10.1023/A:1023005115932

17. Shaffer HJ, Korn DA. Gambling and related mental disorders: a public health analysis. Annu Rev Public Health. (2002) 23:171–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140532

18. Tremblay N, Boutin C, Ladouceur R. Improved self-exclusion program: preliminary results. J Gambl Stud. (2008) 24:505–18. doi: 10.1007/s10899-008-9110-z

19. Nelson SE, Kleschinsky, JH, LaPlante, DA, Shaffer, HJ,. Evaluation of the Massachusetts Voluntary Self-Exclusion Program: June 24, 2015–November 30, 2017. Medford, MA (2018). Available from: https://massgaming.com/wp-content/uploads/Evaluation-of-the-Massachusetts-voluntary-Self-Exclusion-Program-June-24-2015-November-30-2017_6.1.2018_Report.pdf (accessed February 10, 2022).

20. Hing N, Russell AMT, Tolchard B, Nuske EM. Are there distinctive outcomes from self-exclusion? An exploratory study comparing gamblers who have self-excluded, received counseling, or both. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2015) 13:481–96. doi: 10.1007/s11469-015-9554-1

21. Hing N, Nuske E. The self-exclusion experience for problem gamblers in South Australia. Aust Soc Work. (2012) 65:457–73. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2011.594955

22. Gainsbury SM. Review of self-exclusion from gambling venues as an intervention for problem gambling. J Gambl Stud. (2014) 30:229–51. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9362-0

23. McMahon N, Thomson K, Kaner E, Bambra C. Effects of prevention and harm reduction interventions on gambling behaviors and gambling related harm: an umbrella review. Addict Behav. (2019) 90:380–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.048

24. Motka F, Grüne B, Sleczka P, Braun B, Cisneros Örnberg J, Kraus L. Who uses self-exclusion to regulate problem gambling? A systematic literature review. J Behav Addict. (2018) 7:903–16. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.96

25. Fiedler I,. Evaluierung des Sperrsystems in Deutschen Spielbanken (Forschungsbericht). (2015). Contract No: 23.08. Available online at: https://www.bwl.uni-hamburg.de/irdw/dokumente/publikationen/evaluierung-von-sperrsystemen-in-spielbanken.pdf (accessed August 23, 2018).

26. Potenza MN, Fiellin DA, Heninger GR, Rounsaville BJ, Mazure CM. Gambling: an addictive behavior with health and primary care implications. J Gen Intern Med. (2002) 17:721–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10812.x

27. Rolando S, Scavarda A. Italian gambling regulation: justifications and counter-arguments. In: Egerer M, Marionneau V, Nikkinen J, editors. Gambling Policies in European Welfare States. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan (2018). p. 37–57. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-90620-1_3

28. European Commission,. Green Paper on On-line Gambling in the Internal Market. (2011). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0128&from=EN (accessed July 1, 2022).

29. Tammi T, Castren S, Lintonen T. Gambling in Finland: problem gambling in the context of a national monopoly in the European Union. Addiction. (2015) 110:746–50. doi: 10.1111/add.12877

30. Lerkkanen T, Egerer M, Alanko A, Järvinen-Tassopoulos J, Hellman M. Citizens' perceptions of gambling regulation systems: a new meaning-based approach. J Gambl Issues. (2019) 43:84–101. doi: 10.4309/jgi.2019.43.6

31. Glücksspielstaatsvertrag 2021 - GlüStV 2021,. [State Treaty on Gaming]. Staatsvertrag zur Neuregulierung des Glücksspielwesens in Deutschland, vom 29. Oktober 2020. (2021). Available online at: https://www.gluecksspiel-behoerde.de/images/pdf/201029_Gluecksspielstaatsvertrag_2021.pdf (accessed January 26, 2022).

32. Marionneau V, Egerer M, Nikkinen J. How do state gambling monopolies affect levels of gambling harm? Curr Addict Rep. (2021) 8:225–34. doi: 10.1007/s40429-021-00370-y

33. Room R. The monopoly option: obsolescent or a “best buy” in alcohol and other drug control? Soc Hist Alcohol Drugs. (2020) 34:215–32. doi: 10.1086/707513

34. Spillavhengighet Norge,. Pengespillreguleringer fra et brukerståsted (Gambling regulations from a consumer perspective). (2021). Available online at: https://www.spillavhengighet.no/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Pengespillreguleringer-fra-et-brukerperspektiv-Spillavhengighet-Norge.pdf (accessed July 1, 2022).

35. Finkelstein R,. Royal Commission into the Casino Operator License (Reports 1-3). Victorian Government Printer (2021). Available online at: https://content.royalcommission.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-10/The%20Report%20-%20RCCOL%20-%2015%20October%202021.pdf (accessed July 1, 2022).

36. Fogarty M, Taylor-Rodgers, E,. Understanding the Self-Exclusion Process in the ACT. Center for Gambling Research at The Australian National University (2016). Available online at: https://www.gamblingandracing.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/898807/Understand-the-Self-Exclusion-Process-in-the-ACT.pdf (accessed June 14, 2022).

37. Nelson SE, Kleschinsky JH, LaBrie RA, Kaplan S, Shaffer HJ. One decade of self exclusion: Missouri casino self-excluders four to ten years after enrollment. J Gambl Stud. (2010) 26:129–44. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9157-5

38. Hayer T, Brosowski T, Meyer G. Multi-venue exclusion program and early detection of problem gamblers: what works and what does not? Int Gambl Stud. (2020) 20:556–78. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2020.1766096

39. Pickering D, Blaszczynski A, Gainsbury SM. Multivenue self-exclusion for gambling disorders: a retrospective process investigation. J Gambl Issues. (2018) 38:127–51. doi: 10.4309/jgi.2018.38.7

40. Loy J, Sedlacek L, Kraus L. Optimierungsbedarf von Spielersperren. Ergebnisse der VeSpA-Interviewstudie. Sucht. (2020) 66:223–35. doi: 10.1024/0939-5911/a000670

41. Livingstone C, Rintoul A. Moving on from responsible gambling: a new discourse is needed to prevent and minimize harm from gambling. Public Health. (2020) 184:107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.018

42. Kingma SF. Paradoxes of risk management: social responsibility and self-exclusion in Dutch casinos. Cult Organ. (2015) 21:1–22. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2013.795152

43. Fiedler I, Kairouz S, Costes J-M, Weißmüller KS. Gambling spending and its concentration on problem gamblers. J Bus Res. (2019) 98:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.040

Keywords: self-exclusion, gambling, harm, responsible gambling, public health, legal regulations

Citation: Kraus L, Loy JK, Bickl AM, Schwarzkopf L, Volberg RA, Rolando S, Kankainen VE, Hellman M, Rossow I, Room R, Norman T and Cisneros Örnberg J (2022) Self-exclusion from gambling: A toothless tiger? Front. Psychiatry 13:992309. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.992309

Received: 12 July 2022; Accepted: 30 August 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

Charles Livingstone, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Francine Ferland, Centre Intégré Universitaire de Santé et de Services Sociaux de la Capitale-Nationale (CIUSSSCN), CanadaCopyright © 2022 Kraus, Loy, Bickl, Schwarzkopf, Volberg, Rolando, Kankainen, Hellman, Rossow, Room, Norman and Cisneros Örnberg. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ludwig Kraus, a3JhdXNAaWZ0LmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.