- 1Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2Wide Bay Hospital and Health Service, Research Services, Hervey Bay Hospital, Hervey Bay, QLD, Australia

- 3Rural Clinical School, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 4Community Mental Health and Addiction Services, Waikato District Health Board, Hamilton, New Zealand

Introduction: Sexuality is an integral aspect of the human experience that defines an individual. Robust research, substantiated by the World Health Organization, demonstrates that healthy sexuality improves mental health and quality of life. Despite this level of global advocacy and clinical evidence, sexuality and sexual health as determinants of health have been largely overlooked in the mental healthcare of patients being treated under the requirements of a forensic order (forensic patients). In this review, the authors have evaluated the literature related to the sexual development, sexual health, sexual knowledge and risks, sexual experiences, sexual behavior and sexual desires of forensic patients to inform policy and clinical practice. Furthermore, the review explored how forensic patients' sexual healthcare needs are managed within a forensic mental healthcare framework. The paper concludes with recommendations for service providers to ensure that sexual health and sexuality are components of mental health policy frameworks and clinical care.

Methods: An integrative review was utilized to summarize empirical and theoretical literature to provide a greater comprehensive understanding of the sexuality and sexual experiences of forensic patients. This included identifying original qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method research, case reports, case series and published doctoral thesis pertaining to the research topic.

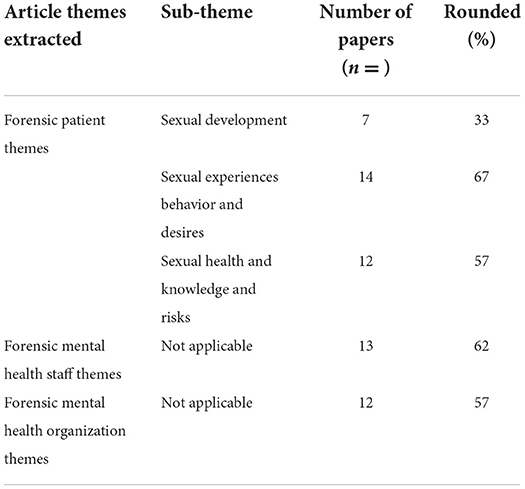

Results: Twenty-one articles were selected for review. We grouped the review findings into three main themes: 1) Forensic patient themes, 2) Forensic mental health staff themes and 3) Forensic mental health organization themes. The review demonstrated scant information on the sexual healthcare needs of forensic patients or how health services manage these needs while the patient is in a hospital or reintegrating into the community.

Conclusion: There is a dearth of evidence-based, individualized or group approaches which clinicians can utilize to assist forensic patients to achieve a healthy sexual life and it is recommended that such services be developed. Before that however, it is essential to have a clear understanding of the sexual healthcare needs of forensic patients to identify areas where this vulnerable population can be supported in achieving optimal sexual health. Urgent changes to clinical assessment are required to incorporate sexual healthcare as a component of routine mental healthcare.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that “sexuality is a central aspect of being human and encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction” (1). The WHO goes further to define sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity” (1). The position of the WHO in relation to sexual health and mental health is substantiated by strong research evidence showing that positive sexual identity, positive sexual experiences, and intimate relationships improve mental health and quality of life (2, 3).

Nevertheless, despite this level of global advocacy and clinical evidence, the constructs of sexuality and sexual health as determinants of health (4) have been largely overlooked in general mental health service delivery, mental health organization design, mental health policy construction, and mental health academic research (5). Moreover, in the specific field of forensic mental health care, there is a paucity of attention.

Forensic mental health care (6) is a term that describes the provision of clinical care under the requirements of a forensic order, that being the outcome of a legal process in which a person has been deemed “not criminally responsible for offending behavior” due to severe mental illness (7, 67). Carroll et al. (7) report that forensic mental health patients usually require prolonged secure hospitalization where the length of stay far exceeds the requirements to manage the symptoms of SMI in this population. Accordingly, one of the goals of forensic mental health services is to enhance the capacity of patients to live successfully within the community once released from inpatient care (8–10). Ong et al. (11) indicate that most forensic patients will eventually be transferred to the community and of those, 73% will require ongoing support to enable sustained community living (12).

In meeting the goal of successfully integrating forensic patients into the community, forensic mental health services are challenged with the conflicting tasks of public protection from recidivism and ethical patient care focused upon mental health recovery principles (13). These divergent principles require a distinctively different clinical and care framework for forensic patients to that of mainstream mental health service patients (7, 14). Nevertheless, there is no conclusive evidence on how forensic patients manage their sexuality, while in a hospital or upon reintegration into the community (2, 10). Compounding this gap, is a deficit in the academic literature regarding forensic patients' sexual development, experiences, health and knowledge (15). Given that sexual health is a determinant of health generally, and the significant impact that sexuality and sexual health can have on mental health, that framework should include support for healthy sexuality and sexual health (15).

The purpose of this review is to evaluate the literature about the sexual development, sexual health, sexual knowledge and risks, sexual experiences, sexual behavior and sexual desires of forensic mental health patients to inform in-hospital and community clinical care policy frameworks and clinical practice. Furthermore, the review will explore how forensic patients' sexual healthcare needs are managed within a forensic mental healthcare framework.

Method

Introduction to method and methodological quality assessment

Over the past 30 years, there has been a substantial increase in the approach, volume, type, direction and complexity of mental health research. Nevertheless, preliminary literature scoping for this review indicated that both meta-analysis and systemic review were not feasible due to insufficient reports being available that would meet the rigorous inclusion criteria required for that level of analysis.

To capture the diversity and breadth of literature that has been produced, this review will utilize an integrative review methodology. An integrative review offers a comprehensive and inclusive methodology which captures theoretical literature and enables the inclusion of retrospective and prospective studies that report quantitative and qualitative research (case reports, case series), experimental (quasi and true experimental) and non-experimental (observational, descriptive, exploratory and survey) studies (16, 17). In similarity to meta-analysis and systematic review, the purpose is to appraise the quality of literature, map out central themes and related concepts and identify areas for future research (18, 19). In addition, Sparbel and Anderson (20) point out that this approach provides the opportunity to consider differing conceptual frameworks, data collection tools, data analysis approaches and synthesis while evaluating the strength of scientific evidence and assigning a weighted assessment against specific data elements. The synthesized output from this broad approach is better able to inform evidence-based practice in fields such as mental healthcare, where “health” and “care” treatment decisions can be somewhat difficult to evaluate against an “effectiveness” measure (21) obtained under meta-analysis or systematic review.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they were in peer-reviewed English language journals reporting any form of original qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method research. We also included case reports, case series and published doctoral thesis as well as reports from the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (22).

Publications (including conference abstracts) that focused on (a) children under 18 years of age; b) intellectually impaired people; c) prisoners; d) non-SMI e.g., severe personality disorder as the main pathology; (e) genetics research; and (f) animal research were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

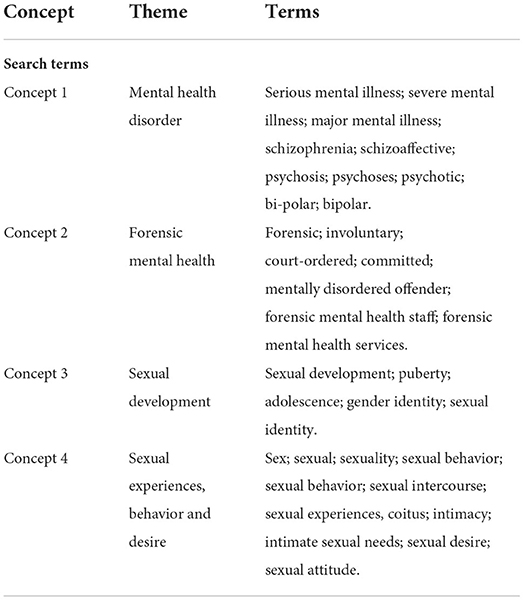

The electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycINFO (PsycNET) were searched from 01/01/1990 until 20/04/2022. The search strategy was conducted using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Descriptor of Health Science (DeCS) terms. Table 1 lists the key terms and words: “mental health disorder,” “forensic mental health,” “sexual development,” “sexual behaviour,” “sexual health” and “sexual knowledge and sexual needs.” We also included studies where participants were professional forensic mental health staff or mental healthcare services. We combined these using the Boolean AND operator adapted for each of the databases and removed duplicate publications.

Publication identification and quality assessment

EB, AR and DN independently screened all articles, first by title, then by abstract for eligibility and then met to reach a consensus for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. A final selection of full-text articles was completed after further screening and consultation with EB, AR, DN and EH.

EB, AR and DN examined and assessed all retrieved publications for study quality using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) criteria for observational studies with a consensus-based weighting score (23). Quality indicators were defined according to integrative review methods and criteria (17, 18, 21) and included (a) sample size; (b) study design; (c) attempts to control for the risk of bias; (d) use of appropriate and standardized measures; (e) use of appropriate statistics; (f) quality of the presentation of the results; and (g) generalisability. The studies were rated on a scale of 1 to 5 based on the report's quality assessment. An overall rating of good, fair, or poor was allocated to each study based on the relevance to our research question.

Data collection and data items were extracted by reviewers using an electronic (Microsoft Excel 2010) pro forma specifying the data items. The following data were extracted from each study: year published, country, participants, methods, setting, study type, aims, problem identification, method of data collection and most important findings.

Results

Study selection

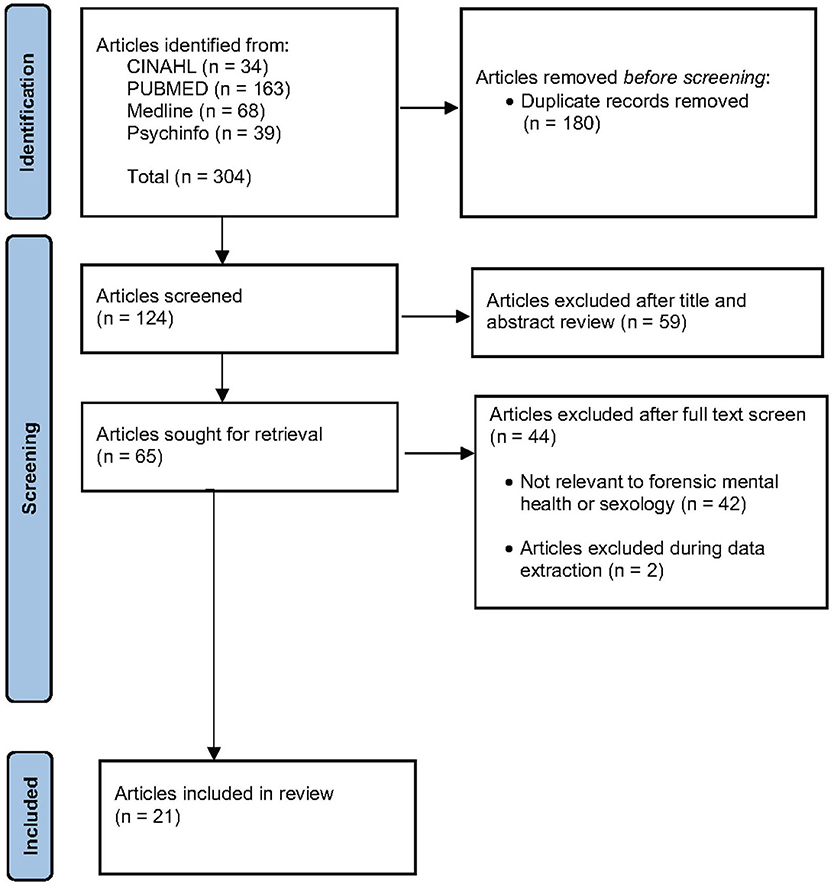

Figure 1 shows that the search returned 304 results, with 124 studies remaining after duplicate studies were deleted. Of these, 59 studies were excluded after the title and abstract review, and 65 were fully reviewed. From these, 21 articles were selected for assessment (Supplementary Table 1).

Study characteristics

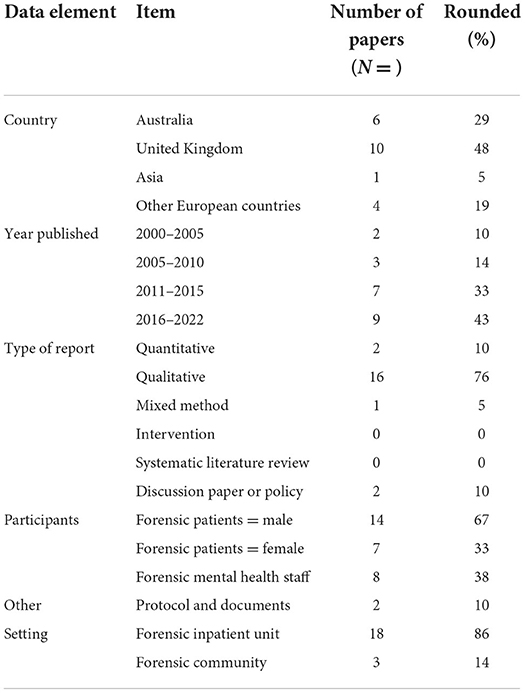

All 21 papers related to forensic mental health patients and comprised patients in inpatient settings and residing in community. Table 2 shows that of the 21 studies, n = 14 (67%) reported on data in a European setting, with just under half (n = 10, 48%) from the United Kingdom. Only n = 6 (29%) Australian specific studies were identified. While studies dated back to 2000, n = 12 (57%) were published in the last 10 years and n = 9 (44%) in the last 5 years.

The majority of studies were qualitative (n = 16), with n = 2 quantitative studies, n = 1 mixed method study, and n = 2 discussion papers. The overwhelming setting for the studies was the forensic inpatient unit (n = 18) with only n = 3 in a community environment. Fourteen studies reported on male populations and seven studies reported on female forensic patients, while eight studies focused on forensic mental health staff. Two studies included protocols and documents only. Of the 21 reviewed articles, the quality rating against the research question was good for n = 11, fair for n = 5 and poor for N = 5.

Forensic patient characteristics

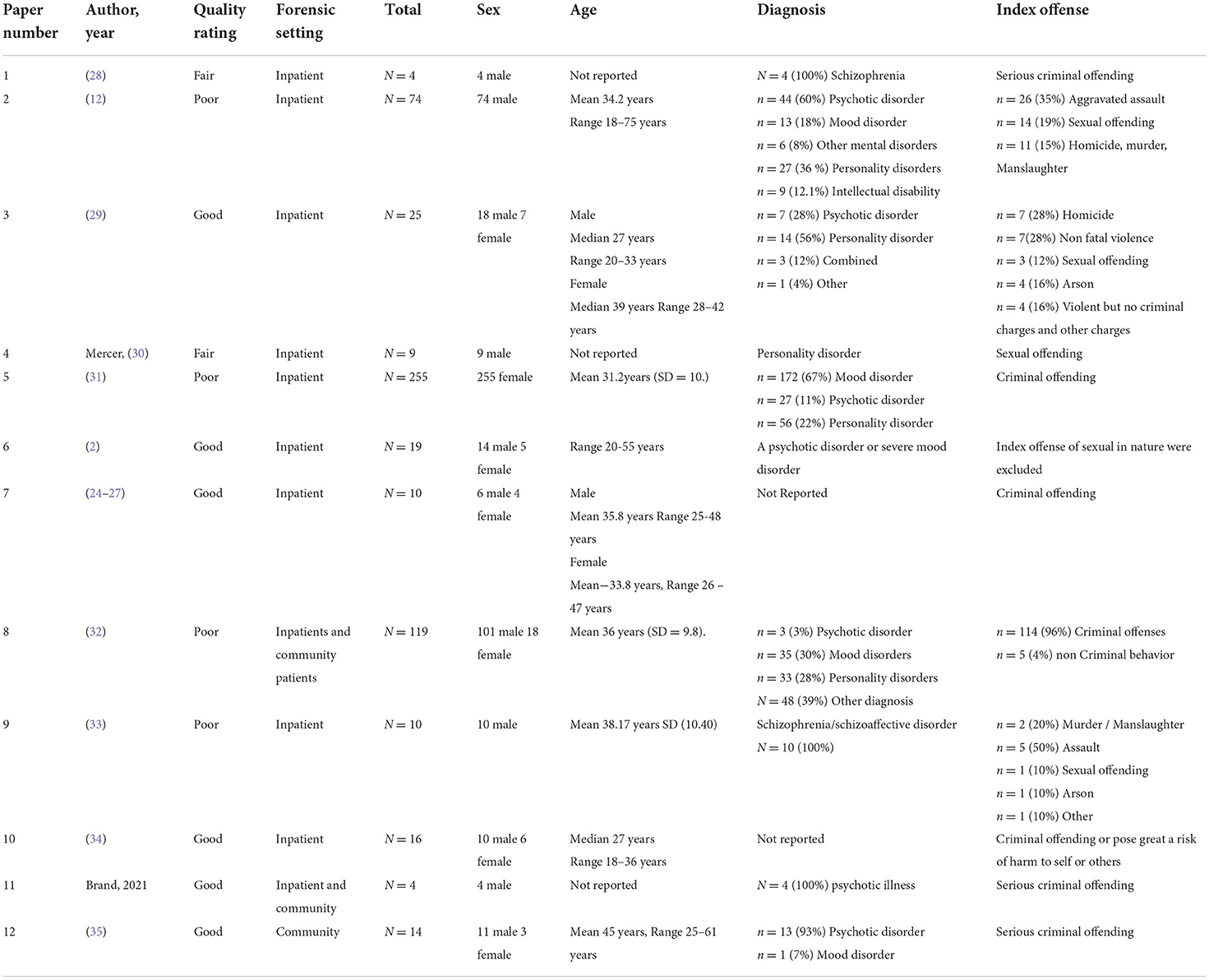

Fifteen articles included and described characteristics of forensic patients. These papers were quality rated as n = 4 poor, n = 2 fair and n = 9 good. Four of the papers by (24–27) were based on the same population. Accordingly, there are 12 forensic patient groups described in this literature review (Table 3).

Nine papers focused exclusively on forensic inpatients, one on forensic outpatients (35) and two on a combination of in and outpatients (32, 36).

All articles, apart from one (31), included male forensic patients, with five articles only including men. Six articles include female forensic patients and one paper by Dolan and Whitworth (31), focused exclusively on female patients (n = 255 patients). Across all articles, 298 females, and 261 male patients with a total of 559 forensic patients were included ranging in age from 18–75 years old.

Ten papers refer to the diagnosis of their participant population, with many referring to multiple diagnostic categories. Nine reported on forensic patients with a psychotic disorder, including schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Of that nine, three populations only consisted of patients with a primary psychotic disorder diagnosis. Out of the total of ten papers, five articles included patients with a mood disorder, including severe depression and bipolar affective disorder. Five of the ten articles have included patients with personality disorder while one author exclusively focused on forensic patients with a personality disorder (30). Only Brown et al. (2) commented on medication, indicating that all his patients were managed by depot antipsychotic medication.

All 12 articles referred to the forensic patient's index offending. Five authors report only “serious” and “criminal” offending. Four authors described the specific offending. Specific offending ranges from arson/fire setting, violent offending, including fatal violent offending (homicide, murder, manslaughter) and non-fatal violent offending (aggravated assault, grievous bodily harm, unlawful wounding) and sexual offending. One author refers exclusively to sexual offending (30), while one author excluded any patients with an index offense of sexual offending (2). Four authors also included non-criminal but high-risk patients.

Main themes of selected studies

For this review, we grouped the study findings into three categories according to the major topics they addressed (patient themes, staff themes, and organizational themes). Table 4 shows that forensic patient-related themes were further categorized by the identified elements of the report—the categorization was not mutually exclusive, for example, sexual health and knowledge often also pertained to sexual behavior and sexual experience, and accordingly, bracket overlap between categories was unavoidable. Nevertheless, the main sub-themes identified in the reports were: sexual development n = 7, sexual experiences, behavior and desires n = 14, and sexual health, knowledge and risks n = 12. Forensic mental health staff themes n = 13 and organization themes were discussed in n = 12 reports.

Synthesis of results

The synthesis focused on the sub-themes identified from the literature: sexual experiences, behavior and desires, sexual health and knowledge and risks, and as well as forensic mental health staff and organizational aspects impacting the patient's sexual health and sexuality. Risks are discussed under sexual health and knowledge given that a lack of sexual knowledge often contributes to poor sexual health and risky sexual behavior (27).

Forensic patient themes

Sexual development

Limited information was identified regarding the physical and sexual development of forensic patients even though initial forensic patient hospitalization often coincided with the critical period of development of adult sexuality and personal relationships (37). Brand et al. (36) acknowledge the bi-directional impact between mental health and sexual health and the particular importance given the young ages at which mental health problems tend to emerge and develop.

Dein and Williams (38) reported that forensic patients spend a large part of their sexual and reproductive lives hospitalized, and Rutherford and Duggan (39) reported that in the United Kingdom, 47% of forensic patient inpatient admissions exceed five or more years with 95% of these patients younger than 64 years. Lindstedt et al. (12) recognized that the impact of this disruption from community life leads to stunted development and maturation, as well as cognitive and social difficulties.

Threats and violence are common among male forensic inpatients (32), and they often have past histories of violent behavior. Previous research identified that violent men strive for power and dominance over others (40, 41). On the contrary, Searle et al. (33) identified a predominantly pro-social development framework for the representation of masculinity in forensic male patients with a psychotic illness.

Sexual experiences, behaviors and desires

Hales et al. (29) noting that the vast majority (n = 24, 96%) of forensic inpatients had been sexually active at some time in their past. Lindstedt et al. (12) indicated that before admission (n = 44, 60%) were married, had been married, or lived in marriage-like relationships while 53% lived alone. Mercer (30) described the solitary practice of pornography and masturbation in forensic male patients in inpatient settings, while Quinn and Happell (27) reported a higher incidence of same-sex experiences amongst patients that identified as heterosexual. Despite the longevity of hospitalization, Ravenhill et al. (34), reported that patients maintain their pre-admission sexual orientation. According to Brown et al. (2), and further illustrated Brand et al. (35), Brand (36) active positive and negative symptoms of SMI, and significant sexual side effects of psychotropic medication further amplify sexual difficulties and negative sexual experiences.

Brown et al. (2) and Dein and Williams (38) recognized the difficulties forensic mental health patients have in initiating or maintaining existing relationships while Cook (42) and Koller and Hantikainen (28) also acknowledged the negative impact of a forensic sentence on relationships and Hales et al. (29) reported that no pre-admission relationship survived forensic hospitalization. The authors relate this to poor interpersonal skills, social withdrawal, lack of self-confidence, low self-esteem, guilt and feelings of shame. Challenges in socializing and communication skills were reported as a significant barriers to sexual intimacy by community forensic mental health patients (35), and this theme of a deficit in sexual intimacy was identified as a strong unmet need for most forensic patients (26) with inpatients pointing to the lack of privacy, private space and private time as the most significant barriers for them to engage in positive sexual experiences (24, 25). Patients associated this loss of privacy with the losses of autonomy, individuality and control in the forensic inpatient population (35, 36, 42).

Regardless of barriers Quinn and Happell (26), reported that forensic patients continue to have sex, often in secrecy (25). Hales et al. (29) reported that 30% (n = 7) of forensic inpatients indicated that they have engaged in some form of sexual activity Quinn and Happell (24), reported that forensic patients discuss sex and intimate relationships and view this as part of normal human behavior. This finding was supported by both Ravenhill et al. (34) and Hales et al. (29) who point out that forensic patients experience sexual feelings, sexual desires, interests and hopes for current and future sexual experiences and relationships. Further evidence of the “normality” of sex was reported by Brand et al. (35) with 12 out of 14 community forensic mental health patients describing a desire for sex with a regular partner. Their desired ideal of sexual intimacy ranged from having sex at least twice per week to having sex daily (an average of 3.71 times per week). In this cohort, only two of fourteen community forensic patients indicated that they were in stable relationships.

According to Koller and Hantikainen (28) as well as Brand et al. (35) forensic patients associate relationships with security, trust, care, a feeling of being loved and a deeper emotional quality. Dein and Williams (38), Hales et al. (29) and Quinn and Happell (24) reported that several forms of intimacy from affection, connection, and relationships to actual sexual activity were perceived as therapeutic and supportive by forensic patients in their recovery.

Sexual health, knowledge and risks

Quinn and Happell (27) and Hales et al. (29) identified a lack of past or ongoing sexual education for forensic patients, however, both authors reported that forensic patients had some awareness of sexual health risks, mostly of sexually transmitted diseases. In the study by Hales et al. (29), 68% (n = 17) of forensic inpatients could define “safe sex,” (specified as condom use) but like Quinn and Happell (27), Hales et al. (29) also concluded that few patients engaged in safe sex practices or use condoms Hales et al. (29) reported that only 40% (n = 10) of forensic inpatients in a high secure hospital in the United Kingdom reported ever using condoms during sexual activity, and just 20% of these (n = 2) claimed regular use. Interestingly, 60% (n = 15) of forensic mental health patients supported the free availability of condoms in the high-security hospital and 64% (n = 16) indicated that they would use them if available (29).

Several authors, including Quinn and Happell (24, 26), Dein and Williams (38), Brown et al. (2) identified legitimate risks to forensic inpatients engaging in sexual behaviors, including the capacity of patients to consent to sexual intercourse, predatory sexual behaviors, sexual coercion and sexual exploitation. Brown et al. (2), Dein and Williams (38) and Quinn and Happell (26) raised the consequences of relationship breakdown and the potential risk to an already vulnerable patient's mental state. Brand et al. (35) reported in a qualitative study on community forensic mental health patients, the “fear of being hurt” in intimate relationships. Risks of unexpected pregnancies in forensic inpatients (8, 24) were also identified.

Despite largely perceiving sexuality and intimacy as positive, Huband et al. (3) identified the forensic patients' need for improving social skills and gaining sexual knowledge. Quinn and Happell (26) recognized that forensic patients required assistance with decisions around intimate sexual relationships. Brand et al. (35) in their qualitative study noted participants being able to identify the areas in which they would like to receive aid, such as knowledge about what “rights” they would have in a relationship, working on their communication skills, and regular medication reviews to maximize the treatment effect of their psychotropic medications, while minimizing side effects.

Forensic mental health staff themes

Brand et al. (36) recognized the gap in the clinical identification and assessment of the sexuality and sexual health needs of forensic patients which in part explains the subsequent lack of management and encouragement of appropriate and safe sexual experiences in a forensic mental health setting. Several authors, including Brown et al. (2), Quinn and Happell (24), and Dein et al. (8) concluded that the most significant forensic mental health staff barriers for forensic patients' positive sexual experiences were risk-related, including risk aversion, safety fears and ambiguity in regards to patients' capacity to consent to sexual activities. Family and public disapproval and negative media responses related to forensic patients' relationships were identified as potential risks by forensic mental health staff in a study by Brown et al. (2). Additionally, inadequate staffing, lack of training (38), personal beliefs, negative attitudes (26), and avoidance of discussion in regards o sexuality and sexual health were identified as hindering patients' positive sexual experiences (24, 25).

Mercer (30) reported that male staff were sympathetic to forensic patients' use of pornography for sexual satisfaction while both Quinn and Happell (26) and Dein and Williams (38) recognized that forensic mental health staff were more accepting and provided more support to the sexual needs of long-term forensic patients as opposed to patients with a shortened admission. Dein et al. (8) indicated that no concerns were raised by staff when forensic patients engage in sexual experiences on unescorted community leave.

In a qualitative study by Brand et al. (35) community forensic patients supported the notion that mental health teams could support their sexual health. Most of these patients reported that they had no issues with being asked questions regarding their sexual health and well-being during regular reviews. Quinn and Happell (25) identified the neglect of preparing patients to engage in sexually intimate relationships in a safe and dignified manner as a major limitation in recovery-orientated forensic mental health care Brand et al. (36) point out that if the concept of a person's sexual health, as part of their holistic care is diminished, their functioning as a whole sexual being is obviated.

Forensic mental health organization themes

The literature showed that there is a lack of comprehensive policies around sexual health within mental health settings (42–45) with several policies prohibiting or actively discouraging sexual expression and relationships (10, 38) based on risk aversion (8, 24) and restricted movement within facilities (46).

Specifically, there is no consensus on what might constitute “best practice” in forensic settings (3, 24, 34) with inconsistencies across institutions and varied attitudes and management of sexual expression and an absence of patient-centered consideration for sexual healthcare needs (47). Mercer et al. (48) and Bartlett et al. (10) both recognized that this policy position contradicts forensic settings as therapeutic and not punitive and non-discriminative. Sexuality expression and sexual and gender identity constructs were often conceptualized in terms of organizational misbehavior (27, 34) and decisions in regards to patients' sexual activities were based on professionals' personal judgment (8). Interesting, while rehabilitation guidelines failed to include support for community forensic patients to have sexual or intimate relationships (49), policies have started to include the provision of education or counseling relating to sexual and emotional relationships. Tiwana et al. (47) identified nine European countries (of which the UK was not one), that have a more positive acknowledgment of patients' rights to sexuality and relationships and allow some kind of sexual expression for forensic inpatients and especially if the permissive approach aids the therapeutic process. These countries have not reported significant problems resulting from this more patient-focused approach.

Discussion

Sexual experiences are important components of normal human behavior (25) and their positive aspects are well recognized (50). The World Health Organization has embraced positive intimate relationships and sex with respect for dignity and privacy, as a fundamental human right (28, 51). Large nationally representative surveys on sexual health and sexuality in developed countries, such as the Australian Study of Health and Relationships (ASHR) (52) and the British National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyle (44) guide policymakers to develop strategies for the improvement of sexual healthcare in the community. Comparable studies in disability and prison populations also demonstrate sexual healthcare deficits (53, 54).

There is an overlap between general mental health patients and forensic patients with SMI. SMI often emerge during adolescence (55–57) with the onset often disrupting crucial sexual developmental milestones, the establishment of sexual identity and gender role perception (57), the acquirement of sexual knowledge, and establishment sexual attitudes and beliefs (58). The academic literature confirms that sexuality in patients with SMI is generally poorly assessed and infrequently explored (59–61) and has been a neglected topic of diagnosis and clinical management (62, 63). The limited literature indicates that the sexual well-being of patients with SMI is associated with complex interactions among psychological, sociological, and biochemical-pharmacological factors (64). SMI patients have a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction (65, 66) and high-risk sexual behaviors (67–70).

There is no conclusive evidence on how forensic patients manage their sexuality while in a hospital or upon reintegration into the community (2, 10). Very limited data is available in the academic literature regarding forensic patients' sexual development, experiences, health and knowledge. No quantitative data on sexual development, experiences, health, and knowledge could be elicited despite broad literature searches. Nevertheless, most forensic patients will eventually be transferred to the community (11) and of those, 73% will require ongoing support to enable sustained community living (12).

Forensic patients face the same challenges as SMI patients with an additional unique tension between risk management and therapeutic intervention (71). For forensic patients, their SMI symptoms are often largely in remission for most of their lengthy admission while they engage in recovery and rehabilitation (6, 8, 71). In Australia, despite adopting a recovery model (72) forensic patients are confronted with sexually restrictive treatment cultures and settings and prohibitive policies that prevent their sexual health needs from being recognized or met. Specifically, a need for privacy, respect and a dignified place for patient intimacy (Quinn & Happel, 2015) is absent in policies and facilities.

The restriction of sexuality and intimacy is contrary to the ethical principle of non-maleficence (8) as well as the forensic recovery model which both supports the normalcy and legitimacy of sexual expression in human experience (34). Detention in a mental health facility as a forensic patient does not automatically imply incapacity to consent to sexual acts (26).

Impact

Poor sexual health negatively impacts relationships, emotional and physical wellbeing (73, 74) and reduces the quality of life for patients with SMI (75–77). Furthermore, legal authority for governing (restricting) sexual expression has human rights implications (10) and even restrictions on sexual media can be interpreted as a breach of human rights (30). Koller (28) recognized that loss of privacy caused by losses of control makes autonomy and individuality impossible.

Prohibitive approaches change the patient's identity as a sexual being (8) by internalizing societal disapproval of their sexuality (2, 38). Patients disconnect with their sexuality and conceptualize sexual experiences as negative, ambiguous and threatening (2, 5). According to Quinn and Happell (24) regulation of sexual behavior serves as a barrier for the development of future relationships. Consequently, hindering patients to experience the potential benefits of intimate relationships including improvement of self-esteem, sense of belonging, mutual support, enjoyment and fulfillment from intimacy and ultimately improvement of a quality-of-life (25). In addition, deprivation and isolation from sexual activity and tactile affection correlate with several negative emotions, such as loneliness, depression, stress, and alexithymia (78).

Restrictions on sexual expression for long durations can potentially destroy existing relationships, prevent the formation of new relationships, and damage the patient's identity as a sexual being (8), and their expectations of future intimate relationships (34). Nevertheless, institutional rules force intimacy and sexual relationships into secrecy (25). Perceiving sexual behavior as misbehavior, the pervasiveness of discourses of risk, vulnerability and appropriateness (34) and the ethos of prohibition impact how rehabilitation is reviewed (2). Brown et al. (2) perfectly conceptualize the “amputated sexuality” that forensic patients develop and which becomes the framework and hindrance (34) for existing and future sexual relationships and expectations that will continue upon discharge in the community (5, 25).

Recommendations

Forensic patient recommendations

Forensic mental health patients would benefit from support to engage in positive and safe sexual experiences and to improve their quality of life. Bartlett et al. (10) emphasize the importance of an established secure social system in the community upon release of forensic patients, and recommends a patient-centered, individualized approach to sexual and emotional relationships. This would require addressing difficult and sensitive questions in several realms: ethics, law, social policy, clinical judgment, politics, religion, and family structures (9).

Forensic mental health staff should offer support through sexual education programs, improvement of socialization and communication skills, and address issues of internalization of stigma and self-esteem, as well as regular medication reviews (35). Sexual education should be made routinely available and incorporated as part of standard rehabilitation to all forensic patients (24, 35).

Sex education will be beneficial in addressing inappropriate sexual behavior while reducing social and sexual isolation (35). This can be further extended to the provision of healthy relationship groups (8). Provisions must be made for the availability of condoms or contraception for all patients (24).

Forensic mental health staff recommendations

There is an absence of any evidence-based, individualized or group approaches which clinicians can utilize to support forensic patients achieve a healthy sexual life (35) and it is highly recommended that such services be developed.

Both Brand et al. (36) and Dein et al. (8) recommend the incorporating of sexuality and sexual health assessments, including assessment of patient's sexual needs and their capacity to form relationships into standard clinical assessment. Incorporating sexuality and sexual health into standard clinical assessments will contribute to supporting holistic forensic mental health recovery and improve quality of life (36) and the management of sexual health issues should form part of clinical care assessment as an essential component of overall well-being (35).

Forensic staff need to recognize the potential importance of childhood sexual abuse in their models of care given the complexity of the association between childhood sexual abuse and psychosocial needs and its impact on successful rehabilitation (31). The education of forensic staff is important to changing attitudes (8) and developing confidence and strategies to respond to normal human sexual behavior adequately and safely (25, 29). Forensic staff should offer support to, as well as provide protection for patients (26).

Forensic mental health organizational recommendations

Respect for human dignity and safeguarding privacy, are very basic human rights that should be respected (28). However safety is always paramount, closely followed by capacity for free consent (38). Recovery-orientated care should include support for patients around their sexual relationship decisions (24) and should provide for discretion in clinical decision-making (26). Quinn therefore advocates for strategies to assist in developing confidence in responding to normal human sexual behavior as a matter of priority (25).

The development of forensic patient-specific policies that are flexible, patient-centered, pro-active, recovery orientated, and support an individualized approach to sexuality and sexual relationships would provide significant improvements (24, 26, 47). Such policies should take into account relevant legislation, social policy, clinical judgment, politics, religion, and family structures risks and the safety of patients and staff (8, 38). Uniform national policy supporting patients' sexual expression would provide significant improvements (47).

Research recommendations

It is essential to have a clear understanding of sexuality and sexual activity of forensic patients to identify areas where this vulnerable population can be supported in achieving optimal sexual health (35).

There is a need for future studies involving forensic patients that can provide both quantitative and qualitative data in terms of sexual development, experiences, health and knowledge (15). Quinn also recognized the need for further research to consider the benefits and risks of patient intimacy and sexual relationships for long-term patients in forensic mental health settings (25).

Data obtained from these studies will be valuable to inform policymaking, guide staff education and the development interventions to ensure positive and safe sexual experiences and improvement of quality of life for forensic patients.

Limitations

The current review presents certain limitations. First, additional terms could have been added to the initial article search (e.g., marriage* or wife* or husband* or girlfriend* or boyfriend*) to be more inclusive. This may have led to the identification of other relevant articles and consequently, more diverse findings. Impediments in the literature review approach centered upon the heterogeneity of forensic mental health patients under the nomenclature of SMI, the dissimilarity in reported service delivery models, the limited reporting of cohort characteristics and matching of participants, and narrow population sampling, exposure measures and statistical analysis and reporting in research papers.

Author contributions

EB, AR, and DN independently screened all articles and then met to reach a consensus for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. A final selection of full-text articles was completed after further screening and consultation with EB, AR, DN, and EH. EB, AR, and DN wrote the initial manuscript. AR and EH edited the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Qhealth in the construction of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.975577/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Kismödi E, Corona E, Maticka-Tyndale E, Rubio-Aurioles E, Coleman E. Sexual rights as human rights: a guide for the WAS declaration of sexual rights. Int J Sex Health. (2017) 29:1–92. doi: 10.1080/1932017, 1353865

2. Brown SD, Reavey P, Kanyeredzi A, Batty R. Transformations of self and sexuality: psychologically modified experiences in the context of forensic mental health. Health (London). (2014) 18:240–60. doi: 10.1177/1363459313497606

3. Huband N, Furtado V, Schel S, Eckert M, Cheung N, Bulten E, et al. Characteristics and needs of long-stay forensic psychiatric inpatients: a rapid review of the literature. Int J Forensic Ment Health. (2018) 17:45–60. doi: 10.1080/14999013.2017.1405124

4. Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Australia's Health 2016. Determinants of health. Canberra: AIHW

5. Mccann E, Donohue G, Jager D, Nugter J, Stewart AJ, et al. Sexuality and intimacy among people with serious mental illness: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. (2019) 17:74–125. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003824

6. Dickens G, Langé A, Picchioni M. Labelling people who are resident in a secure forensic mental health service: user views. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. (2011) 22:885–94. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2011.607509

7. Carroll A, Lyall M, Forrester A. Clinical hopes and public fears in forensic mental health. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. (2004) 15:407–425. doi: 10.1080/14789940410001703282

8. Dein KE, Williams PS, Volkonskaia I, Kanyeredzi A, Reavey P, Leavey G. Examining professionals' perspectives on sexuality for service users of a forensic psychiatry unit. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2016) 44:15–23 doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.08.027

9. Perlin ML. “Everybody is making love/or else expecting rain”: Considering the sexual autonomy rights of persons institutionalized because of mental disability in forensic hospitals and in Asia. Washington Law Rev. (2008) 83:481–512.

10. Bartlett P, Mantovani N, Cratsley K, Dillon C, Eastman N. ‘You may kiss the bride, but you may not open your mouth when you do so': policies concerning sex, marriage and relationships in english forensic psychiatric facilities. Liverp Law Rev. (2010) 31:155–176. doi: 10.1007/s10991-010-9078-5

11. Ong K, Carroll A, Reid S, Deacon A. Community outcomes of mentally disordered homicide offenders in Victoria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2009) 43:775–780. doi: 10.1080/00048670903001976

12. Lindstedt H, Söderlund A, Stålenheim G, Sjödén PO. Mentally disordered offenders' abilities in occupational performance and social participation. Scand J Occup Ther. (2009) 11:118–127. doi: 10.1080/11038120410020854

13. Warner R. Does the scientific evidence support the recovery model? Psychiatrist. (2018) 34:3–5. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.109.025643

14. Timmons D. Forensic psychiatric nursing: a description of the role of the psychiatric nurse in a high secure psychiatric facility in Ireland. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2010) 17:636–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01581.x

15. Brand E, Ratsch A, Heffernan E. The sexual development, sexual health, sexual experiences, and sexual knowledge of forensic mental health patients: a research design and methodology protocol. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:651839. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.651839

16. Evans D, Pearson A. Systematic reviews: gatekeepers of nursing knowledge. J Clin Nurs. (2001) 10:593–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-200100517.x

17. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. (2005) 52:546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

18. Christmals D, Gross J. An integrative literature review framework for postgraduate nursing research reviews. J Res Med Sci. (2017) 5:7–15.

19. Russell CL. An overview of the integrative research review. Prog Transplant. (2005) 15:8–13. doi: 10.1177/152692480501500102

20. Sparbel KJ, Anderson MA. Integrated literature review of continuity of care: part 1, conceptual issues. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2000) 32:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00017.x

21. Souza MTD, Silva MD, Carvalho RD. Integrative review: what is it? how to do it? Einstein (São Paulo). (2010) 8:102–06. doi: 10.1590/s1679-45082010rw1134

22. Coyle A. European Committee for the Prevention of Torture. Bristol: Prisons of the World Policy (2021).

23. West S, King V, Carey TS, Lohr KN, Mckoy N, Sutton SF, et al. Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). (2002) 1–11.

24. Quinn C, Happell B. Consumer sexual relationships in a forensic mental health hospital: perceptions of nurses and consumers. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 24:121–9. doi: 10.1111/inm.12112

25. Quinn C, Happell B. Sex on show issues of privacy and dignity in a forensic mental health hospital: nurse and patient views. J Clin Nurs. (2015) 24:2268–76. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12860

26. Quinn C, Happell B. Supporting the sexual intimacy needs of patients in a longer stay inpatient forensic setting. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2016) 52:239–47. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12123

27. Quinn C, Happell B. Exploring sexual risks in a forensic mental health hospital: perspectives from patients and nurses. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 36:669–677 doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1033042

28. Koller K, Hantikainen V. Privacy of patients in the forensic department of a psychiatric clinic: a phenomenological study. Nurs Ethics. (2002) 9:347–60. doi: 10.1191/0969733002ne520oa

29. Hales H, Romilly C, Davison S, Taylor PJ. Sexual attitudes, experience and relationships amongst patients in a high security hospital. Crim Behav Ment Health. (2006) 16:254–63. doi: 10.1002/cbm.636

30. Mercer D. Girly mags and girly jobs: pornography and gendered inequality in forensic practice. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2013) 22:15–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00837.x

31. Dolan M, Whitworth H. Childhood sexual abuse, adult psychiatric morbidity, and criminal outcomes in women assessed by medium secure forensic service. J Child Sex Abus. (2013) 22:191–208. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2013.751951

32. Henrichs J, Bogaerts S, Sijtsema J, Klerx-Van Mierlo F. Intimate partner violence perpetrators in a forensic psychiatric outpatient setting: criminal history, psychopathology, and victimization. J Interpers Violence. (2015) 30:2109–2128. doi: 10.1177/0886260514552272

33. Searle R, Hare D, Davies B, Morgan SL. The impact of masculinity upon men with psychosis who reside in secure forensic settings. J Forensic Psychol Pract. (2018) 20:69–80. doi: 10.1108/JFP-05-2017-0014

34. Ravenhill JP, Poole J, Brown SD, Reavey P. Sexuality, risk, and organisational misbehaviour in a secure mental healthcare facility in England. Cult Health Sex. (2020) 22:1382–97. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2019.1683900

35. Brand E, Nagaraj D, Ratsch A, Heffernan E. A qualitative study on sexuality and sexual experiences in community forensic mental health patients in Queensland, Australia. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:832139. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.832139

36. Brand E, Ratsch A, Heffernan E. Case report: the sexual experiences of forensic mental health patients. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:651834. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.651834

37. Mcgorry PD, Purcell R, Goldstone S, Amminger GP. Age of onset and timing of treatment for mental and substance use disorders: implications for preventive intervention strategies and models of care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2011) 24:301–06. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283477a09

38. Dein K, Williams PS. Relationships between residents in secure psychiatric units: are safety and sensitivity really incompatible? Psychiatr Bull R Coll Psychiatr. (2018) 32:284–7. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.106.011478

39. Rutherford M, Duggan S. Forensic mental health services: facts and figures on current provision. Br J Forensic Pract. (2008) 10:4–10. doi: 10.1108/14636646200800020

40. Robinson T, Watt S. Where No One Goes Begging“: Converging Gender, Sexuality, and Religious Diversity. Thousand Oaks, CA, SAGE Publications (2001).

41. Möller-Leimkühler AM. The gender gap in suicide and premature death or: why are men so vulnerable? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neuro Sci. (2003) 253:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0397-6

42. Cook JA. Sexuality and people with psychiatric disabilities. Sex Disabil. (2000) 18:195–206. doi: 10.1023/A:1026469832339

43. Mcclure L. Where is the sex in mental health practice? A discussion of sexuality care needs of mental health clients. J Ethics Ment Health. (2012) 7:1–5.

44. Mitchell KR, Mercer CH, Ploubidis GB, Jones KG, Datta J, Field N, et al. Sexual function in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet. (2013) 382:1817–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1

45. Welch SJ, Clements GW. Development of a policy on sexuality for hospitalized chronic psychiatric patients. Can J Psychiatry. (1996) 41:273–9. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100503

46. Wright ER, Gayman M. Sexual networks and HIV risk of people with severe mental illness in institutional and community-based care. AIDS Behav. (2005) 9:341–53. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9008-z

47. Tiwana R, Mcdonald S, Vollm B. Policies on sexual expression in forensic psychiatric settings in different European countries. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2016) 10:5. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0037-y

48. Mercer CH, Tanton C, Prah P, Erens B, Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, et al. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet. (2013) 382:1781–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8

49. Wolfson P, Holloway F, Killaspy H. Enabling Recovery for People With Complex Mental Health Needs: A Template for Rehabilitation Services. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists (2009).

50. Dudeck M. Sexualität von allgemeinpsychiatrischen und Maßregelpatienten. Psychotherapeut. (2019) 64:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s00278-019-0365-x

51. Gascoyne S, Hughes E, Mccann E, Quinn C. The sexual health and relationship needs of people with severe mental illness. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2016) 23:338–43. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12317

52. Australian Study of Health and Relations. Sex in Australia 2, Summary. (2014). Available online at: http://www.ashr.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/sex_in_australia_2_summary_data.pdf (accessed 3 March 2021)

53. Earle S. (2001), Disability, facilitated sex and the role of the nurse. J Adv Nurs. (2648) 36:433–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01991.x

54. Perlin ML, Lynch A. “All his sexless patients”: Persons with mental disabilities and the competence to have sex. Washington Law Rev. (2014) 89:257–1467. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2412543

55. Mcmillan E, Adan Sanchez A, Bhaduri A, Pehlivan N, Monson K, Badcock P, et al. Sexual functioning and experiences in young people affected by mental health disorders. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 253:249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.009

56. Tolman DL, Mcclelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: a decade in review, 2000-2009. J Res Adolesc. (2011) 21:242–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00726.x

57. Redmond C, Larkin M, Harrop C. The personal meaning of romantic relationships for young people with psychosis. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2010) 15:151–170. doi: 10.1177/1359104509341447

58. Yung AR, Killackey E, Hetrick SE, Parker AG, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkoetter J, et al. The prevention of schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2007) 19:633–46. doi: 10.1080/09540260701797803

59. Hughes E, Edmondson AJ, Onyekwe I, Quinn C, Nolan F. Identifying and addressing sexual health in serious mental illness: Views of mental health staff working in two National Health Service organizations in England. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2018) 27:966–74. doi: 10.1111/inm.12402

60. Malik P. Sexual dysfunction in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2007) 20:138–42. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f6c4

61. Quinn C, Browne G. Sexuality of people living with a mental illness: a collaborative challenge for mental health nurses. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2009) 18:195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00598.x

63. Wainberg ML, Cournos F, Wall MM, Norcini Pala A, Mann CG, Pinto D, et al. Mental illness sexual stigma: implications for health and recovery. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2016) 39:90–6. doi: 10.1037/prj0000168

64. Ma MC, Chao JK, Hung JY, Sung SC, Chao IC, et al. Sexual activity, sexual dysfunction, and sexual life quality among psychiatric hospital inpatients with schizophrenia. J Sex Med. (2018) 15:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.01008

65. de Boer MK, Castelein S, Wiersma D, Schoevers RA, Knegtering H. The facts about sexual (Dys)function in schizophrenia: an overview of clinically relevant findings. Schizophr Bull. (2015) 41:674–86. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv001

66. Marques TR, Smith S, Bonaccorso S, Gaughran F, Kolliakou A, Dazzan P, et al. Sexual dysfunction in people with prodromal or first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. (2012) 201:131–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101220

67. Smith S, Herlihy D. Sexuality in psychosis: dysfunction, risk and mental capacity. Adv Psychiatr Treat. (2018) 17:275–82. doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.107.003715

68. Meade CS, Sikkema KJ. HIV risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2005) 25:433–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.001

69. Walsh C, Mccann E, Gilbody S, Hughes E. Promoting HIV and sexual safety behaviour in people with severe mental illness: a systematic review of behavioural interventions. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2014) 23:344–54. doi: 10.1111/inm.12065

70. Dyer JG, Mcguinness TM. Reducing HIV risk among people with serious mental illness. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. (2008) 46:26–34. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20080401-06

71. Davison S. Specialist forensic mental health services. Crim Behav Ment Health. (2004) 14 Suppl 1:S19–24. doi: 10.1002/cbm.604

72. Commonwealth of Australia. A National framework for recovery-oriented mental health services: guide for practitioners and providers. In: Commonwealth of Australia (ed.). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (2013).

73. Dickerson FB, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl J, Goldberg RW, Fang LJ, Dixon LB. Sexual and reproductive behaviors among persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. (2004) 5:1299–1301. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1299

74. Just MJ. The influence of atypical antipsychotic drugs on sexual function. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2015) 11:1655–61. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S84528

75. Bushong ME, Nakonezny PA, Byerly MJ. Subjective quality of life and sexual dysfunction in outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Sex Marital Ther. (2013) 39:336–46. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2011.606884

76. Montejo AL, Montejo L, Navarro-Cremades F. Sexual side-effects of antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2015) 28:418–23. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000198

77. Ostman M. Low satisfaction with sex life among people with severe mental illness living in a community. Psychiatry Res. (2014) 216:340–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.009

Keywords: integrative review, sexuality, sexual health, forensic, severe mental illness

Citation: Brand E, Ratsch A, Nagaraj D and Heffernan E (2022) The sexuality and sexual experiences of forensic mental health patients: An integrative review of the literature. Front. Psychiatry 13:975577. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.975577

Received: 22 June 2022; Accepted: 29 August 2022;

Published: 26 September 2022.

Edited by:

Thomas Nilsson, University of Gothenburg, SwedenReviewed by:

Mary V. Seeman, University of Toronto, CanadaMaris Taube, Riga Stradinš University, Latvia

Copyright © 2022 Brand, Ratsch, Nagaraj and Heffernan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elnike Brand, s4454530@student.uq.edu.au

Elnike Brand

Elnike Brand