95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 26 August 2022

Sec. Addictive Disorders

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.951682

This article is part of the Research Topic Women and Substance Use: Specific Needs and Experiences of Use, Others’ Use and Transitions Towards Recovery View all 17 articles

Introduction: People who inject drugs have a substantial risk for HIV infection, especially women who inject drugs (WWID). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a highly-effective HIV prevention drug, is uncommonly studied among WWID, and we aimed to synthesize existing knowledge across the full PrEP continuum of care in this population.

Methods: We systematically searched for peer-reviewed literature in three electronic databases, conference abstracts from three major HIV conferences, and gray literature from relevant sources.

Eligibility criteria included quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods studies with primary data collection reporting a PrEP-related finding among WWID, and published in English or Spanish between 2012 and 2021. The initial search identified 2,809 citations, and 32 were included. Data on study characteristics and PrEP continuum of care were extracted, then data were analyzed in a narrative review.

Results: Our search identified 2,809 studies; 32 met eligibility requirements. Overall, awareness, knowledge, and use of PrEP was low among WWID, although acceptability was high. Homelessness, sexual violence, unpredictability of drug use, and access to the healthcare system challenged PrEP usage and adherence. WWID were willing to share information on PrEP with other WWID, especially those at high-risk of HIV, such as sex workers.

Conclusions: To improve PrEP usage and engagement in care among WWID, PrEP services could be integrated within gender-responsive harm reduction and drug treatment services. Peer-based interventions can be used to improve awareness and knowledge of PrEP within this population. Further studies are needed on transgender WWID as well as PrEP retention and adherence among all WWID.

Injecting drug use is a major driver of HIV infection globally, with up to ten percent of HIV infections attributable to injecting drug use (1). People who inject drugs (PWID) are 22 times more likely to acquire HIV compared to those who do not, and one in every eight individuals who injects drugs is living with HIV (1, 2). Women who inject drugs (WWID) are particularly at increased risk of HIV infection compared to men, primarily as a consequence of high-risk injection and sexual practices, such as sharing needles and engaging in condomless sex (3). This is due to a variety of structural factors including the criminalization of drug use, which disproportionately affects women who use drugs (4), gendered injecting practices, such as women being forced to share needles (5), and gender-based violence, which is associated with high-risk sexual behaviors and avoidance of health services among WWID (3). Additionally many WWID participate in transactional sex or sex work, which is associated with higher rates of HIV due to gendered power dynamics, which increase women's exposure to sexual violence and limit their abilities to negotiate safe sex (4, 6).

HIV risk among WWID is compounded by the intersection of stigma related to both substance abuse and gender particularly due to gendered expectations of morality and motherhood (7). This stigma impacts WWID within and outside of injecting communities (8). Outside of injecting communities, this stigma can diminish trust in the health system and health providers, which may decrease health-seeking behaviors and access to HIV-related and other health services, including harm reduction services (5, 8, 9). Moreover, harm reduction services for people who inject drugs (PWID), are often male-oriented, meaning they serve primarily male clientele and lack the staff or facilities to address the distinct needs of women (5). As a consequence, WWID often do not have their unique needs met in these settings and may be forced to engage in unsafe injecting.

A possible solution to decrease both injection and sexual-related HIV risk among WWID is pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (10). PrEP is highly effective in preventing HIV (11–13), and its use has been expanding rapidly since the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended it for high-risk populations in 2015 (14, 15). By 2019, 180 countries had adopted these recommendations, but with only an estimated 626,000 PrEP users in only 77 countries, primarily in North and South America and sub-Saharan Africa (16).

Even in high-income countries, WWID are not identified as a priority group for PrEP interventions. Effective PrEP interventions should consider all high-risk populations and include the full PrEP continuum of care, including PrEP initiation, adherence, and retention or disengagement in care (17). While there is a growing number of studies on WWID and PrEP, there is no synthesis of the current evidence base. One study previously examined the PrEP care cascade among PWID, but it only focused on the US and did not examine gender differences (18). A global review of the PrEP care cascade focused more broadly on women who use drugs and female sex workers (19). However, it did not consider transgender women, who are at higher risk of HIV (2), it did not consider the full PrEP cascade, and it only included peer-reviewed literature. As such, the aim of this study is to examine the entire PrEP continuum of care among women (cis and trans) who inject drugs globally.

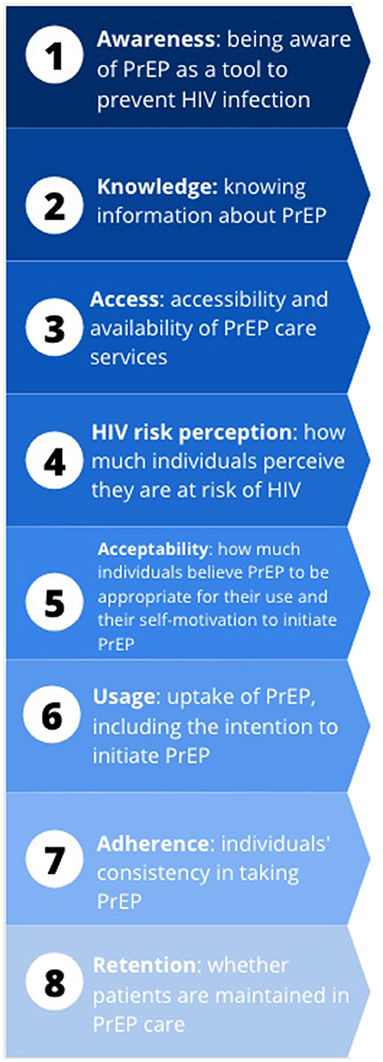

We reviewed studies that considered any part of the PrEP care cascade among women (cis and trans) who inject drugs globally. For each study, we analyzed at least one of the following variables, based on the framework by Nunn et al. (17): PrEP awareness, PrEP knowledge, access to PrEP care, HIV risk perception, PrEP acceptability, PrEP usage, PrEP adherence, or retention in PrEP care (see Figure 1) or any other relevant PrEP variables.

Figure 1. PrEP continuum of care variables and definitions Nunn et al. (17)

Any quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods study with primary data collection was eligible for inclusion. We did not include commentaries, editorials, or reviews. However, the bibliographies of relevant reviews were searched for relevant articles for inclusion. Publications must have been published from 2012 onwards, when PrEP was first approved by the US Federal Drug Administration to prevent HIV in at-risk populations. We only included publications which focused specifically on women or studies that present gender differences of relevant results. All publications must have been reported in either English or Spanish.

A comprehensive literature search was completed in PubMed/Medline, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. The search string included subject headings and keywords related to HIV and PrEP, the PrEP care continuum, injecting drug use, and gender/sex (see Table 1). We reviewed the references of included papers to check for other relevant studies. We also searched for abstracts in three major, relevant conference proceedings: the International AIDS Conference, HIV Research for Prevention conference, and the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science. Additionally, we searched clinicaltrials.gov, the WHO's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and for additional gray literature from Harm Reduction International, the Women in Harm Reduction International Network, the International Network of People Who Use Drugs, the International Drug Policy Consortium, Correlation European Harm Reduction Network, and the New York Academy of Medicine's Gray Literature Database.

All records were imported into Mendeley and duplicated records were removed. Two reviewers (DG and TMW) screened titles and abstracts of records identified through the search strategy, and disagreements were resolved between the two. Full texts of records were assessed for inclusion by two reviewers (DG and JD); disagreements were resolved with another reviewer (TMW).

Data were extracted by two reviewers (DG and LvS) into a pre-specified data extraction template in Microsoft Excel. Information included authorship, title, study aims, design, setting, population, sample size, PrEP care continuum findings, and other relevant findings. Data were then validated by another reviewer (TMW) and differences were reconciled among two reviewers (DG and TMW). Narrative synthesis, organized according to each step of the PrEP care cascade, was performed to describe the characteristics and findings of all included studies.

Two reviewers (DG and LvS) assessed risk of bias for each study individually and when scores differed, discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers. Risk of bias was assessed using the 2018 Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (20), which allows for evaluation of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies. Each study received a quality score ranging from 0 (meeting no criteria) to 5 (meeting all criteria) based on the MMAT criteria.

The initial search yielded 3,145 records, and 2,809 remained after removing duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, 83 articles remained to be assessed for eligibility at the full-text level. Fifty-one articles were excluded in total. Articles were excluded because they did not provide gender disaggregated results (n = 21), did not include injecting drug use in their analyses (n = 20), did not show PrEP outcomes (n = 6), or did not use primary data collection (n = 4; Figure 2).

Thirty-two studies were included in this review (see Table 2). Studies primarily took place in the United States (21, 22, 26–31, 35, 36, 39–47, 49–51) but also in Thailand (37, 38), Canada (25), India (24), Kenya (23), and Malaysia (32). One study included participants globally (34) and another included those in Europe and Asia only (33). Study populations were primarily adult (18+) PWID (24, 25, 33–39, 43, 44, 46, 47, 52) or WWID only (22, 23, 26–31, 49, 50). Other populations included female sex workers (41), transgender women (32), prison inmates (21), individuals at high-risk of HIV (51), women with substance abuse disorders (42), and opiate users (40, 48). Sample sizes ranged from 9 (23) to 10,538 (24) participants. Across the studies, where sample sizes of WWID were provided, 3,216 WWID were included. The average quality score for the studies was 4.2, and studies were not excluded based on quality rating (see Table 3).

Data on awareness of PrEP among WWID was reported in 14 studies (22, 24, 31, 32, 39–42, 44, 46, 50–53). Awareness of PrEP among WWID varied (range: 7–66%). Walters et al. (50) conducted a study among WWID in New York City, and showed that WWID who participated in transactional sex were more than three times more likely to be aware of PrEP than those who did not (aOR = 3.32; 95% CI = 1.22–9.0). In this same study, WWID who had a conversation about HIV prevention at syringe exchange programs were almost eight times more likely to be aware of PrEP than those who did not (aOR = 7.61; 95% CI = 2.65–21.84) (50). According to a study by McFarland et al. (39) among PWID in San Francisco (USA), WWID were more likely to be aware of PrEP than their male counterparts (63.4 vs. 52.7%, respectively, p = 0.025) (39). In a study on PrEP awareness among PWID in Philadelphia, injecting drug users that were aware of PrEP were more likely to be women (35.5 vs. 23.9%, p = 0.03) (44). In another study comparing PrEP awareness among various high-risk groups in New York, WWID had decreased odds of PrEP awareness compared to men who have sex with men (AOR: 0.18; 95% CI: 0.05–0.6) (51). In one study that examined awareness among individuals with opiate use disorder, there were no significant differences in PrEP awareness by gender (40).

Knowledge of PrEP among WWID was assessed in three studies (31, 34, 39). In a study conducted by McFarland et al. (39), 38.9% of WWID knew that PrEP could prevent HIV transmission from sharing injection paraphernalia, and this knowledge did not differ between genders (39). Footer et al. examined PrEP knowledge among 16 WWID and female sex workers, and reported that knowledge was “low” among these populations, but this was not quantified (31). In contrast, in the study conducted among members of the International Network of People who use Drugs (INPUD) (34) most participants expressed that they had sufficient information on PrEP.

Four studies examined access to PrEP care (33, 34, 43, 51). Notably, members of INPUD expressed the ethical concerns over providing WWID with knowledge about PrEP in settings where PrEP is not available (34). In Roth et al.'s study examining PrEP acceptance and access among PWID, 47.7% of WWID had seen a primary care physician in the past 6 months and 15.4% had been to an annual women's wellness exam (43). In the Walters et al. study among high-risk groups in New York City and Long Island, 25 and 32% of WWID, respectively, had exposure to HIV prevention professionals (50).

Regarding where WWID preferred to receive care, Roth et al. indicated that WWID preferred to be screened for HIV at the syringe exchange program rather than traditional sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics. In particular, 90% of WWID indicated that they preferred HIV testing at a mobile van clinic (43). Similarly, members of INPUD also noted that community based services would be necessary for PrEP to be accessible to WWID given stigma toward PWID and the criminalization of drug use (33).

Four studies considered HIV risk perception (21, 24, 26, 54). Two studies quantitatively examined HIV risk perception among WWID (pooled sample size = 128) which averaged at 53.6% of individuals perceiving themselves to be at high risk of HIV (29, 48). In a PrEP demonstration study among WWID in Philadelphia, USA, participants indicated that periods of high drug consumption and engagement in transactional sex elevated their perceived risk of HIV. This also increased their desire to use PrEP (29).

In a qualitative study of WWID in Philadelphia, USA, women who were regularly engaged in harm reduction services had lower perceptions of HIV risk compared to women not engaged in such services. Overall, WWID were particularly concerned about obtaining HIV from sexual assault and accidental needlesticks, which positively impacted their decision to initiate PrEP (26).

In one survey examining HIV risk perception among people in prison in the United States, injecting drug use was positively correlated with perceived risk of HIV seroconversion in prison, and this relationship was slightly stronger among women than men (p < 0.01) (21). One study that examined awareness of and willingness to use PrEP among PWID and men who have sex with men (MSM) in India found that low perceived self-risk of HIV infection was the most common reason for being unwilling to use PrEP overall (24). Among those unwilling to use PrEP, 9% of WWID reported a lack of self-perceived HIV risk as the reason for their unwillingness.

Data on PrEP acceptability among WWID were reported in 16 studies (22–26, 32–36, 40, 41, 43, 46, 48, 52). Results varied widely between studies (range: 23–100% acceptability). In the studies conducted among members of INPUD, PrEP was only acceptable if provided in a comprehensive package of harm reduction services as participants prioritized safe injection equipment over PrEP for HIV prevention.

In seven studies conducted among PWID in India (24) and the United States (35, 36, 40, 47, 48, 52), gender was not significantly associated with PrEP acceptability. However, in a study among PWID in Canada, WWID were more willing to use PrEP compared to men (OR 1.52, p = 0.028) (25). Similarly, in a study among individuals attending syringe exchange programs in New Jersey, WWID were more willing to use PrEP than their male counterparts (88.9 vs. 71.0%; p < 0.02) (43). Beyond gender, factors which influenced the acceptability of PrEP included concerns regarding side-effects (25, 33, 34, 43, 55), and access to health professionals (22, 34, 43). Participants who found PrEP more acceptable were those that engaged in sex work (25, 46) or transactional sex (43), had experienced sexual violence (41), had multiple recent sexual partners (25, 43), had other medical conditions (47), shared injection equipment (41, 46, 47), believed they were at high risk of HIV (48), and were of younger age (25, 41).

Results on the impact of injecting drug use on acceptability were mixed. In one study that examined PrEP acceptability among trans-women in Malaysia, injecting drug use was negatively associated with acceptability (B = −1.17, p = 0.001) (32). Interestingly, among female sex workers in Baltimore (USA), injecting drug use was not associated with acceptability of PrEP (41).

One study by Schneider et al. examined the acceptability of different forms of PrEP use and demonstrated higher acceptance of oral (62%) and arm-injection (60%) administration compared to implants (26%), vaginal gels (26%), vaginal rings (29%), abdomen injection (22%) and intravenous infusion (15%) among WWID (46).

Data on the number of WWID that used or intended to use PrEP was collected in seven studies (22, 28, 38, 39, 46, 49, 54). In one study in Philadelphia intention to use PrEP was 88% among WWID. In this study, intention to use PrEP was associated with having fewer concerns discussing sexual history and drug use with their health provider (p < 0.01) (49).

Regarding usage of PrEP among PWID, there was no clear difference of PrEP use by gender across studies. Martin et al. found no significant difference in PrEP uptake by gender (OR 1.2, p = 0.16) in Thailand (38). However, McFarland et al. found that in San Francisco women were more likely to have used PrEP than heterosexual men (3.7% of women vs. 0% of heterosexual men, p = 0.007) (39).

Barriers to PrEP use among WWID included access to a doctor, homelessness, and potential theft of medication (22). Among WWID at a syringe service program in Philadelphia, factors that increased the odds of initiating PrEP included reporting sexual assault (p = 0.003), higher income (p = 0.06), frequency of syringe service programs attendance (p = 0.001), and inconsistent condom use (p = 0.03) (28).

Data on adherence to PrEP among WWID were collected in four studies. Across studies, adherence ranged from 5.6 to 52.3% (29, 37, 38, 45). In an analysis of 95 WWID in a PrEP demonstration project in Philadelphia, approximately half reported taking all PrEP medication at follow-ups, though prevention-effective levels were detected in only one participant urinalysis (45). Barriers to adherence included unstable housing and lack of storage for their medication. Adherence was also challenged by women's entrance to institutions that did not provide PrEP, such as some drug treatment and correctional facilities. Additionally, adherence depended on women's levels of drug-use and perceived HIV-risk at the time. When WWID felt at risk for HIV, they were more motivated to take PrEP. However, when WWID perceived they were at low risk of HIV (e.g., when abstaining from drug use) they discontinued use (29).

In the Bangkok Tenovir Study, which analyzed PrEP adherence in PWID by various demographic factors, women were more adherent compared to men (p = 0.006) (37). In the open-label extension of the Bangkok Tenovir Study, only 14% of WWID that returned for at least one follow-up visit had >90% adherence to PrEP. In the multivariable analysis, men were more likely to be adherent compared to WWID (OR = 1.9; 95% CI 1.0–3.6) (38).

Retention in PrEP care was assessed by the open-label extension of the Bangkok Tenovir Study (38) and the PrEP demonstration study in Philadelphia (45). The majority (69%) of Bangkok women returned for at least one follow-up clinic visit, but gender was not significantly associated with their likelihood of returning for a follow-up visit (38). In the PrEP demonstration study, retention fell in follow-ups at weeks 1 (93.7%), 12 (61.2%), and 24 (44.2%) among women in Philadelphia, and was most associated with access to syringe service programs (45).

One relevant PrEP variable that was outside of the PrEP continuum of care but was mentioned in five studies was PrEP communication (27, 39, 40, 42, 54). In one study that considered the willingness to share information on PrEP among WWID, participants were willing to share information with 83% of people in their network (54). They were more likely to share information if the individual was homeless (UOR 3.3; 95% CI 1.5–7.6), an injecting drug user (UOR 2.3; 95% CI 1.1–4.7), engaged in transactional sex (UOR 4.5; 95% CI 1.6–12.5) or had a perceived high-risk of HIV (UOR 1.1; 95% CI 1.1–1.2). The study did not compare rates of sharing information between men and women. In another study examining PrEP communication among WWID, conversations having to do with PrEP occurred in 30/57 various relationships examined (27). In this study, individuals were motivated to have conversations of PrEP based on perceived HIV risk, gender similarity, to increase emotional connectedness and potential support from a peer, and when a negative outcome was perceived from not disclosing PrEP use.

Two studies considered PrEP communication in terms of conversations with the healthcare provider (39, 42). One study found no difference in gender in discussions of PrEP with healthcare provider (39). However, in another study examining drug treatment contexts and women's decision-making about PrEP a healthcare provider indicated that she never considered raising PrEP with heterosexual women clients (42).

This review of the PrEP continuum of care among WWID included 3,216 WWID across 32 studies. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review stratified across the PrEP continuum of care to focus solely on this population, a highly vulnerable and marginalized population who are often overlooked in HIV research and prevention (5). WWID face several gender-specific challenges of drug use. Generally, WWID fall on the bottom of the hierarchy among PWID. This means that they may be forced to share needles or engage in risky income-generating behaviors to sustain drug use, such as sex work (56). This increases their risk for a variety of health harms, including higher mortality rates, levels of risky injecting, levels of risky sexual behavior, prevalence of blood-borne viruses, and psychological harm compared to men. WWID are also more likely to have a sexual partner who also injects drugs and be dependent on them for drugs compared to men (57). Many women who use drugs in such relationships also experience physical and psychological violence, which may preclude them from accessing harm reduction services, such as initiating PrEP uptake (57, 58). Furthermore, gender-based social responsibilities, such as child rearing, may prevent women from accessing health and harm reduction services generally. Notably, the fear of having children being apprehended may prevent WWID from accessing health services, including harm reduction services (59). As such, it is crucial to understand the gendered dynamics of injection drug use and harm reduction, an in particular, the PrEP continuum of care.

Despite the great need, there is no data from the ECDC on PrEP among WWID. In fact, data from ECDC show that more than 90% of current PrEP users in European countries belong to the MSM community (60). There is a strong need to scale up PrEP to other marginalized communities, such as WWID, if we are to reach the Sustainable Development Goals, and even in high-income countries with large-scale implementation (e.g., France, Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the US), it is important to ensure that efforts are made to guarantee that these communities are reached at a sufficient scale. This review considered PrEP awareness (n = 14), PrEP knowledge (n = 3), access to PrEP care (n = 4), HIV risk perception (n = 4), PrEP acceptability (n = 16), PrEP usage (n = 7), PrEP adherence (n = 4), and retention in PrEP care (n = 1) among WWID. We also considered a new PrEP variable, PrEP communication (n = 5), that is highly relevant for improving awareness, knowledge, and usage in this population.

This review found that awareness, knowledge, and usage of PrEP in WWID is generally low. Suboptimal awareness was also found among other high-risk populations for HIV including women who use drugs at large (19, 61), women who engage in sex work (19), as well as MSM (62). However, WWID who were aware about PrEP were interested in its use, as PrEP acceptability was relatively high in most studies investigating it. Furthermore, acceptability was associated with HIV risk perception and engagement in high-risk sexual or injection practices. WWID are generally aware of and interested in lowering their risks of contracting HIV. However, as our review demonstrates, several structural issues challenge the ability of WWID to do so, including homelessness, sexual violence, unpredictability of drug use, and access to the healthcare system. A qualitative study by Felsher et al. (29) demonstrated that for some WWID, although there is a desire to use PrEP, it simply is overshadowed by other basic needs, such as access to food and shelter, generating an income and access to drugs. Whereas, one study performed in Kenya and South Africa showed drug use to be a PrEP-disrupting behavior (63), Felsher et al. showed that during periods where the women are not engaged in drug use, they are not as inclined to use PrEP as they feel their risk is lower (29). Risk of HIV transmission through non-injection routes (e.g., condomless sex) may also increase during periods of drug use (64).

The gap between PrEP acceptance and usage underscores the need for better provision of PrEP to WWID. WWID should be specified as a key population in PrEP technical guidelines, which is currently not the case in most countries, including in high-income countries (65). Further challenging PrEP awareness and usage in this population is the lack of engagement of WWID with the traditional healthcare system, as several studies in this review noted. This is unsurprising given the stigma, social inequality, and marginalization experienced by WWID, which leads to lack of healthcare access (66). As such, solutions to introduce PrEP at women's health clinics or other mainstream health services, as suggested by other research on women who use drugs (19), may fail to reach this population, as WWID indicated that they preferred to access care elsewhere.

Given these results, integrating PrEP services with low-threshold harm reduction and drug treatment services for PWID may be a more practical solution to engage this population in comparison to mainstream health services. In fact, members of INPUD highlighted that PrEP should only be administered as part of a comprehensive package of harm reduction (33, 34). Our findings align with previous research for engaging PWID in care (67–70). The studies in our review revealed that women that were more engaged in harm reduction services, such as syringe exchange programs, were more likely to be aware of and use PrEP. Furthermore, these services should have a holistic and gender-based approach to meet the unique needs and gender-based vulnerabilities of WWID, such as housing insecurity and sexual violence. In particular, integrating additional sexual health services in these settings could improve engagement in care for this population. In fact, a review of a pilot program which integrated reproductive healthcare within a needle and syringe program indicated that WWID were very satisfied with the services provided (71).

In addition to highlighting the need for integrating services, our results on PrEP communication underscore the role of peers in spreading knowledge and awareness about PrEP among WWID. Studies in this review indicated that WWID were very likely to share information on PrEP to other WWID, especially if they were deemed to be at high risk of HIV. This is in line with research on services for PWID which acknowledge the importance of engaging peers (68, 72, 73). For example, in Indonesia peer support was shown to help with HIV treatment initiation and adherence to HIV care among PWID. Furthermore, PWID were able to regain trust in the healthcare system and stay motivated to retain in HIV care (73). Similarly, in Senegal, researchers indicated that peer-led outreach among PWID could serve as an important part of harm reduction programs (72), Given their shared lived experiences, and potentially shared social networks, peers can help provide emotional and social support needed to engage with and maintain care. They can also diffuse harm reduction information through their social networks. However, rather than just communicating behavior change, peers can de-stigmatize drug use and encourage meaningful involvement of PWID in interventions aimed at improving their wellbeing (72). As such, harm reduction programs should involve peers provided Through a shared lived experience with adequate structural support to help generate trust and improve engagement in health and harm reduction services.

Our review highlighted several gaps in the evidence base. Most importantly, many studies (n = 21) were excluded because they did not stratify results by gender, which challenges understanding the needs of WWID, who may have different experiences compared to their male counterparts. It is crucial that future research on people who inject drugs disaggregate between men and women to improve service provision for both men and women. Alongside this, research and recruitment methods should be tailored to the needs of WWID to encourage their participation (e.g., female researchers in community-based settings). There was also a lack of geographical variation across studies, with most studies taking place in major metropolitan cities in the United States and an absence of studies from South America. Additionally, there was only one study that fitted our review criteria that examined transgender women. However, there is a great need for more research on trans WWID given that trans-women are at higher risk of contracting HIV (2). Lastly, very few studies examined PrEP adherence and retention among WWID, which are needed to improve engagement in care.

Several limitations exist in this systematic review. First, the number of studies and lack of geographic diversity limit the generalizability of our findings. This may have been as a result of our language restriction. Had we extended the inclusion criteria to other languages, the number of studies included in this review may have increased. The lack of geographic diversity meant we could not interpret differences in the PrEP continuum of care across different countries, or indeed, regions. Another intrinsic limitation of this review was the small proportion of studies on the PrEP continuum of care which included WWID and provided gender disaggregated data. In addition, when included, WWID were often only a small proportion of the study sample sizes. This also created difficulties in comparing results across studies. Therefore, this review and the findings within may change as more studies and reviews on the topic emerge over time.

HIV research addressing the PrEP continuum of care under-recognizes the unique needs of and challenges faced by WWID, and especially transgender women. Steps of the care continuum, such as PrEP awareness and knowledge, may be improved by engaging WWID where they access health and/or social services, including in community and peer-based interventions. To improve PrEP usage and engagement in care among WWID, technical guidance should specify WWID as a key population for PrEP interventions. Furthermore, PrEP services could be integrated within gender-responsive harm reduction and drug treatment services as well as correctional services. Further studies are needed on PrEP retention and adherence among WWID, including in high-income countries where PrEP implementation has moved beyond demonstration projects to national programs.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

DG conceptualized this study. DG, TW, and JD scanned and assessed all potential articles for inclusion. DG drafted the manuscript with significant input from all other authors. All authors approved the final draft for submission.

The project that gave rise to these results received support from a fellowship from La Caixa Foundation (ID 100010434) awarded to DG. The fellowship code is LCF/BQ/DI20/11780008.

Authors acknowledge support to ISGlobal from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through the Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019–2023 Programme, and from the Government of Catalonia through the CERCA Programme.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. United Nations Office on Drugs Crime. World Drug Report. (2020). Available online at: https://wdr.unodc.org/wdr2020/index2020.html (accessed June 17, 2021).

2. UNAIDS. Miles To Go Closing Gaps Breaking Barriers Righting Injustices. (2018). Available online at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/miles-to-go_en.pdf (accessed June 17, 2021).

3. Iversen J, Page K, Madden A, Maher L. HIV, HCV, and health-related harms among women who inject drugs: implications for prevention and treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2015) 69(Suppl. 2):S176–81. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000659

4. Strathdee SA, West BS, Reed E, Moazan B, Azim T, Dolan K. Substance use and hiv among female sex workers and female prisoners: risk environments and implications for prevention, treatment, and policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2015) 69:S110. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000624

5. El-Bassel N, Strathdee SA. Women who use or inject drugs: an action agenda for women-specific, multilevel, and combination HIV prevention and research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2015) 69:S182–90. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000628

6. Kerr T, Shannon K, Ti L, Strathdee S, Hayashi K, Nguyen P, et al. Sex work and HIV incidence among people who inject drugs. AIDS. (2016) 30:627. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000948

7. Meyers SA, Earnshaw VA, D'Ambrosio B, Courchesne N, Werb D, Smith LR. The intersection of gender and drug use-related stigma: a mixed methods systematic review and synthesis of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2021) 223:108706. doi: 10.1016/J.DRUGALCDEP.2021.108706

8. Medina-Perucha L, Scott J, Chapman S, Barnett J, Dack C, Family H. A qualitative study on intersectional stigma and sexual health among women on opioid substitution treatment in England: implications for research, policy and practice. Soc Sci Med. (2019) 222:315–22. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2019.01.022

9. Azim T, Bontell I, Strathdee SA. Women, drugs and HIV. Int J Drug Policy. (2015) 26(Supple. 1):S16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.003

10. Braksmajer A, Senn TE, McMahon J. The potential of pre-exposure prophylaxis for women in violent relationships. AIDS Patient Care STDS. (2016) 30:274. doi: 10.1089/APC.2016.0098

11. Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O'reilly KR, Koechlin FM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS. (2016) 30:1973–83. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001145

12. Spinner CD, Boesecke C, Zink A, Jessen H, Stellbrink HJ, Rockstroh JK, Esser S. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): a review of current knowledge of oral systemic HIV PrEP in humans. Infection. (2016) 44:151–8. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0850-2

13. Dolling DI, Desai M, McOwan A, Gilson R, Clarke A, Fisher M, et al. An analysis of baseline data from the PROUD study: An open-label randomised trial of pre-exposure prophylaxis. Trials. (2016) 17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1286-4

14. Zablotska IB, Baeten JM, Phanuphak N, McCormack S, Ong J. Getting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to the people: opportunities, challenges and examples of successful health service models of PrEP implementation. Sex Health. (2018) 15:481–4. doi: 10.1071/SH18182

15. World Health Organization. Guideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Guidelines. (2015). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK327115/ (accessed June 17, 2021).

16. Schaefer R, Schmidt H-MA, Ravasi G, Mozalevskis A, Rewari B.B, Lule F, et al. Adoption of guidelines on and use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis: a global summary and forecasting study. Lancet HIV. (2021) 8:e502–10. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00127-2

17. Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, Mayer KH, Mimiaga M, Patel R, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS. (2017) 31:731–4. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001385

18. Mistler CB, Copenhaver MM, Shrestha R. The pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) care cascade in people who inject drugs: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. (2021) 25:1490–506. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02988-x

19. Glick JL, Russo R, Jivapong B, Rosman L, Pelaez D, Footer KH, et al. The PrEP care continuum among cisgender women who sell sex and/or use drugs globally: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. (2020) 24:1312–33. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02733-z

20. Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. (2018) 34:285–91. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

21. Alarid LF, Hahl JM. Seroconversion risk perception among jail populations: a call for gender-specific HIV prevention programming. J Correct Heal care Off J Natl Comm Correct Heal Care. (2014) 20:116–26. doi: 10.1177/1078345813518631

22. Bass S, Brajuha J, Kelly P, Coleman J. Sometimes You Gotta Choose: An Indepth Qualitative Analysis on Perceptions of the Barriers and Facilitators to use and Adhere to PrEP in Women Who Inject Drugs. Philadelphia: APHA's 2019 Annual Meeting and Expo (2019).

23. Bazzi AR, Biancarelli DL, Childs E, Drainoni ML, Edeza A, Salhaney P, et al. Limited knowledge and mixed interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis for hiv prevention among people who inject drugs. AIDS Patient Care STDS. (2018) 32:529–537. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0126

24. Belludi A, McFall AM, Solomon SS, Celentano DD, Mehta SH, Srikrishnan AK, et al. Awareness of and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among people who inject drugs and men who have sex with men in India: results from a multi-city cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0247352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247352

25. Escudero DJ, Kerr T, Wood E, Nguyen P, Lurie MN, Sued O, et al. Acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PREP) among people who inject drugs (PWID) in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav. (2015) 19:752–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0867-z

26. Felsher M, Ziegler E, Smith LR, Sherman SG, Amico KR, Fox R, et al. An exploration of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) initiation among women who inject drugs. Arch Sex Behav. (2020) 49:2205–12. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01684-0

27. Felsher M, Koku E, Lankenau S, Brady K, Bellamy S, Roth AM. Motivations for PrEP-related interpersonal communication among women who inject drugs: a qualitative egocentric network study. Qual Health Res. (2020) 31:86–99. doi: 10.1177/1049732320952740

28. Felsher M, Bellamy S, Piecara B, Van Der Pol B, Laurano R, Roth AM. Applying the behavioral model for vulnerable populations to pre-exposure prophylaxis initiation among women who inject drugs. AIDS Educ Prev. (2020) 32:486–92. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2020.32.6.486

29. Felsher M, Ziegler E, Amico KR, Carrico A, Coleman J, Roth AM. “PrEP just isn't my priority”: Adherence challenges among women who inject drugs participating in a pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) demonstration project in Philadelphia. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 275:113809. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113809

30. Felsher M, Dutra K, Monseur B, Roth AM, Latkin C, Falade-Nwulia O. The influence of PrEP-related stigma and social support on PrEP-Use disclosure among women who inject drugs and social network members. AIDS Behav. (2021) 25:3922–3932. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03312-x

31. Footer KHA, Lim S, Rael CT, Greene GJ, Carballa-Diéguez A, Giguere R, et al. Exploring new and existing PrEP modalities among female sex workers and women who inject drugs in a U.S. city. AIDS Care Psychol Soc Med Asp. (2019) 31:1207–13. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1587352

32. Galka JM, Wang M, Azwa I, Gibson B, Lim SH, Shrestha R, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention and PrEP implementation preferences among transgender women in Malaysia. Transgender Heal. (2020) 5:258–66. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0003

33. International Network of People who Use Drugs. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for People Who Inject Drugs: Community Voices on Pros, Cons, and Concerns. London: International Network of People who Use Drugs (2016).

34. International Network of People who Use Drugs. Key Populations' Values and Preferences for HIV, Hepatitis, and STI Services: A Qualitative Study. London: International Network of People who Use Drugs (2021).

35. Jo Y, Bartholomew TS, Doblecki-Lewis S, Rodriguez A, Forrest DW, Tomita-Barber J, et al. Interest in linkage to PrEP among people who inject drugs accessing syringe services; Miami, Florida. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0231424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231424

36. Kuo I, Olsen H, Patrick R, Phillips II G, Magnus M, Opoku J, et al. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among community-recruited, older people who inject drugs in Washington, DC. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2016) 164:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.044

37. Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. The impact of adherence to preexposure prophylaxis on the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs. Aids. (2015) 29:819–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000613

38. Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Chaipung B, et al. Factors associated with the uptake of and adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in people who have injected drugs: an observational, open-label extension of the Bangkok Tenofovir study. lancet HIV. (2017) 4:e59–66. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30207-7

39. McFarland W, Lin J, Santos G-MM, Arayasirikul S, Raymond HF, Wilson E. Low PrEP awareness and use among people who inject drugs, San Francisco, 2018. AIDS Behav. (2020) 24:1290–3. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02682-7

40. Metz VE, Sullivan MA, Jones JD, Evans E, Luba R, Vogelman J, et al. Racial differences in HIV and HCV risk behaviors, transmission, and prevention knowledge among non-treatment-seeking individuals with opioid use disorder. J Psychoactive Drugs. (2017) 49:59–68. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2016.1259518

41. Peitzmeier SM, Tomko C, Wingo E, Sawyer A, Sherman S, Glass N, et al. Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis and vaginal rings for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Baltimore, MD. AIDS Care Psychol Soc Med Asp. (2017) 29:1453–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1300628.Acceptability

42. Qin Y, Price C, Rutledge R, Puglisi L, Madden LM, Meyer JP. Women's decision-making about PrEP for HIV prevention in drug treatment contexts. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. (2020) 19:1–11. doi: 10.1177/2325958219900091

43. Roth AM, Aumaier BL, Felsher MA, Welles SL, Martinez-Donate AP, Chavis M, et al. An exploration of factors impacting preexposure prophylaxis eligibility and access among syringe exchange users. Sex Transm Dis. (2018) 45:217–21. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000728

44. Roth A, Tran N, Piecara B, Welles S, Shinefeld J, Brady K. Factors associated with awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for hiv among persons who inject drugs in philadelphia: national hiv behavioral surveillance, 2015. AIDS Behav. (2019) 23:1833–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2293-0

45. Roth AM, Tran NK, Felsher M, Gadegbeku AB, Piecara B, Fox R, et al. Integrating HIV preexposure prophylaxis with community-based syringe services for women who inject drugs: results from the project SHE demonstration study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2021) 86:e61–70. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002558

46. Schneider KE, White RH, O'Rourke A, Kilkenny ME, Perdue M, Sherman SG, et al. Awareness of and interest in oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention and interest in hypothetical forms of PrEP among people who inject drugs in rural West Virginia. AIDS Care. (2021) 33:721–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2020.1822506

47. Sherman SG, Schneider KE, Nyeong Park J, Allen ST, Hunt D, Chaulk CP, et al. PrEP awareness, eligibility, and interest among people who inject drugs in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2019) 195:148–55. doi: 10.1016/J.DRUGALCDEP.2018.08.014

48. Stein M, Thurmond P, Bailey G. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among opiate users. AIDS Behav. (2014) 18:1694–700. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0778-z

49. Tran NK, Felsher M, Pol B Van Der, Bellamy SL, McKnight J, Roth AM. Intention to initiate and uptake of PrEP among women who injects drugs in a demonstration project: an application of the theory of planned behavior. AIDS Care. (2021) 33:746–53. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2021.1874267

50. Walters SM, Reilly KH, Neaigus A, Braunstein S. Awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women who inject drugs in NYC: the importance of networks and syringe exchange programs for HIV prevention. Harm Reduct J. (2017) 14:40. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0166-x

51. Walters SM, Rivera A V, Starbuck L, Reilly KH, Boldon N, Anderson BJ, et al. Differences in awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis and post-exposure prophylaxis among groups at-risk for HIV in New York State: New York City and Long Island, NY, 2011-2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2017) 75(Suppl. 3):S383–91. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001415

52. Corcorran MA, Tsui JI, Scott JD, Dombrowski JC, Glick SN. Age and gender-specific hepatitis C continuum of care and predictors of direct acting antiviral treatment among persons who inject drugs in Seattle, Washington. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2022) 220:108525. doilink[10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108525]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108525

53. Biello KB, Bazzi AR, Mimiaga MJ, Biancarelli DL, Edeza A, Salhaney P, et al. Perspectives on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization and related intervention needs among people who inject drugs. Harm Reduct J. (2018) 15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0263-5

54. Felsher M, Koku E, Bellamy SL, Mulawa MI, Roth AM. Predictors of willingness to diffuse PrEP information within ego-centric networks of women who inject drugs. AIDS Behav. (2021) 25:1856–63. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-03115-6

55. Bazzi AR, Yotebieng KA, Agot K, Rota G, Syvertsen JL. Perspectives on biomedical HIV prevention options among women who inject drugs in Kenya. AIDS Care Psychol Soc Med Asp. (2018) 30:343–6. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1363369

56. International AIDS Society,. Women Who Inject Drugs: Overlooked, yet Visible. (2019). Available online at: https://www.iasociety.org/Web/WebContent/File/2019__IAS__Brief__Women_who_inject_drugs.pdf (accessed December 3, 2020).

57. Roberts A, Mathers, B, Degenhardt, L,. Women Who Inject Drugs: A Review of Their Risks, Experiences Needs. (2010). Available online at: http://www.idurefgroup.unsw.edu.au (accessed December 3, 2020).

58. Valencia J, Alvaro-Meca A, Troya J, Gutiérrez J, Ramón C, Rodríguez A, et al. Gender-based vulnerability in women who inject drugs in a harm reduction setting. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0230886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230886

59. Stone R. Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Heal Justice. (2015) 3:2. doi: 10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5

60. European Centers for Disease Control,. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Europe Central Asia. Monitoring Implementation of the Dublin Declaration on Partnership to Fight HIV/AIDS in Europe Central Asia – 2018/19 Progress Report. (2019). Available online at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/pages/legalnotice.aspx (accessed January 18, 2022).

61. Zhang C, McMahon J, Simmons J, Brown L, Nash R, Liu Y. Suboptimal HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness and willingness to use among women who use drugs in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. (2019) 23:2641. doi: 10.1007/S10461-019-02573-X

62. Yi S, Tuot S, Mwai GW, Chhim K, Pal K, Igbinedion E, et al. Awareness and willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. (2017) 20:21580. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21580

63. Namey E, Agot K, Ahmed K, Odhiambo J, Skhosana J, Guest G, et al. When and why women might suspend PrEP use according to perceived seasons of risk: implications for PrEP-specific risk-reduction counselling. Cult Heal Sex. (2016) 18:1081–91. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1164899

64. Elsesser S, Oldenburg C, Biello K, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Egan JE, et al. Seasons of risk: anticipated behavior on vacation and interest in episodic antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among a large national sample of U.S. Men who have sex with Men (MSM). AIDS Behav. (2016) 20:1400–7. doi: 10.1007/S10461-015-1238-0

65. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in the EU/EEA and the UK: Implementation, Standards and Monitoring Operational Guidance. Solna: The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2019).

66. Paquette CE, Syvertsen JL, Pollini RA. Stigma at every turn: health services experiences among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. (2018) 57:104. doi: 10.1016/J.DRUGPO.2018.04.004

67. Pinto RM, Berringer KR, Melendez R, Mmeje O. Improving PrEP implementation through multilevel interventions: a synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behav. (2018) 22:3681–91. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2184-4

68. Smith M, Elliott L, Hutchinson S, Metcalfe R, Flowers P, McAuley A. Perspectives on pre-exposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs in the context of an hiv outbreak: a qualitative study. Int J Drug Policy. (2021) 88:103033. doi: 10.1016/J.DRUGPO.2020.103033

69. Coleman RL, McLean S. Commentary: the value of PrEP for people who inject drugs. J Int AIDS Soc. (2016) 19(7(Suppl 6)):21112. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21112

70. Alistar SS, Owens DK, Brandeau ML. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis in a portfolio of prevention programs for injection drug users in mixed HIV epidemics. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e86584. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0086584

71. Owens L, Gilmore K, Terplan M, Prager S, Micks E. Providing reproductive health services for women who inject drugs: a pilot program. Harm Reduct J. 2020 171. (2020) 17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/S12954-020-00395-Y

72. Stengel CM, Mane F, Guise A, Pouye M, Sigrist M, Rhodes T. “They accept me, because I was one of them”: formative qualitative research supporting the feasibility of peer-led outreach for people who use drugs in Dakar, Senegal. Harm Reduct J. (2018) 15:9. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0214-1

73. Iryawan AR, Stoicescu C, Sjahrial F, Nio K, Dominich A. The impact of peer support on testing, linkage to and engagement in HIV care for people who inject drugs in Indonesia: qualitative perspectives from a community-led study. Harm Reduct J. (2022) 19:1–13. doi: 10.1186/S12954-022-00595-8/TABLES/1

Keywords: pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), PrEP care continuum, women who inject drugs, human immunodeficiency virus, people who inject drugs

Citation: Guy D, Doran J, White TM, van Selm L, Noori T and Lazarus JV (2022) The HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis continuum of care among women who inject drugs: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 13:951682. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.951682

Received: 24 May 2022; Accepted: 25 July 2022;

Published: 26 August 2022.

Edited by:

Guilherme Messas, Faculty of Medical Sciences, BrazilReviewed by:

Weiming Tang, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Guy, Doran, White, van Selm, Noori and Lazarus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jeffrey V. Lazarus, amVmZnJleS5sYXphcnVzQGlzZ2xvYmFsLm9yZw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.