- 1Department of Psychiatry, University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli”, Naples, Italy

- 2Department of Basic Medical Science, Neuroscience, and Sense Organs, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy

- 3Department of Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health (DINOGMI), Section of Psychiatry, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

- 4Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences (DISCAB), University of L'Aquila, L'Aquila, Italy

- 5Psychiatric Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, AOUP, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

- 6Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy

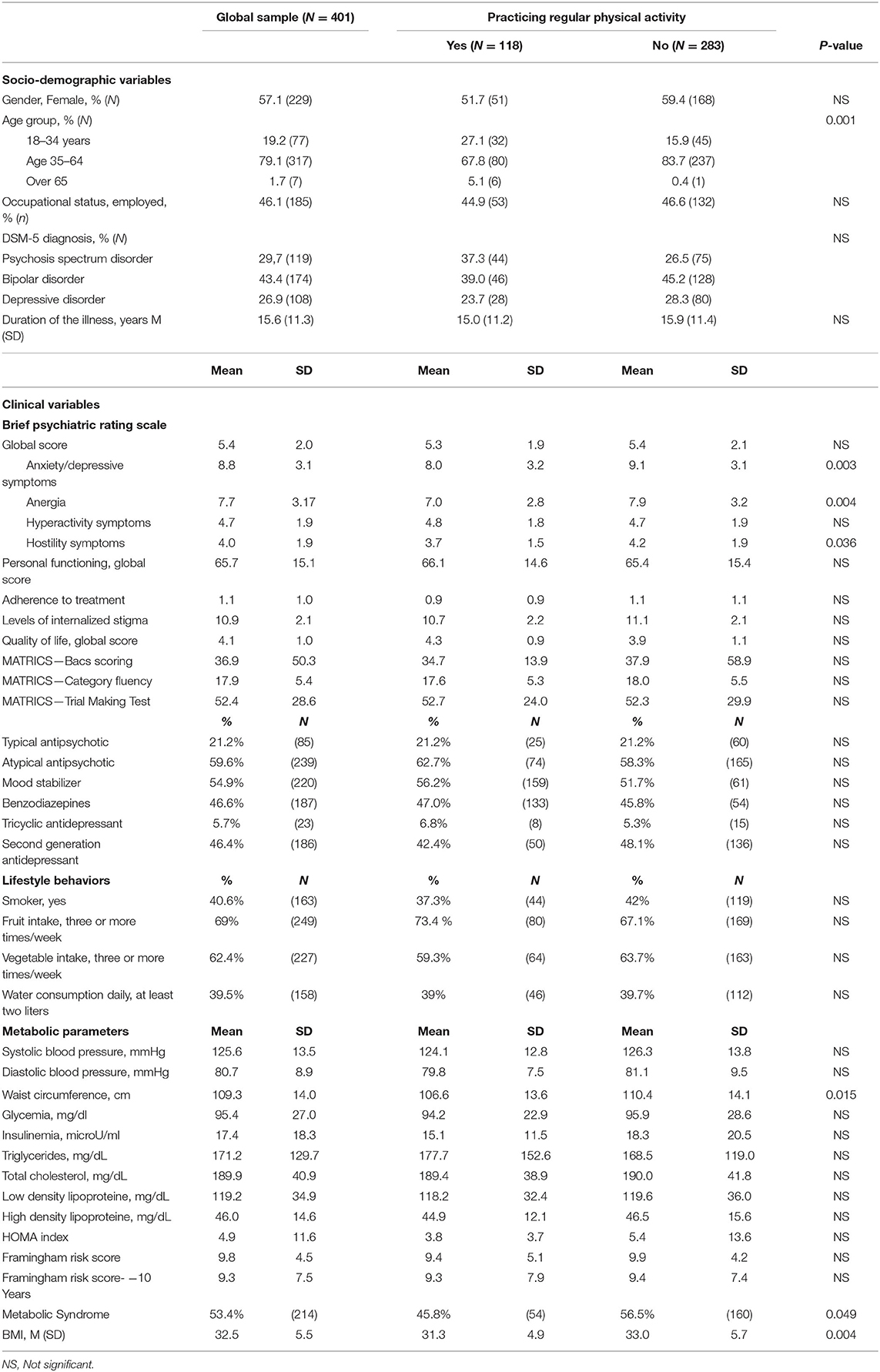

Compared with the general population, people with severe mental disorders have significantly worse physical health and a higher mortality rate, which is partially due to the adoption of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, such as heavy smoking, use of alcohol or illicit drugs, unbalanced diet, and physical inactivity. These unhealthy behaviors may also play a significant role in the personal and functional recovery of patients with severe mental disorders, although this relationship has been rarely investigated in methodologically robust studies. In this paper, we aim to: a) describe the levels of physical activity and recovery style in a sample of patients with severe mental disorders; b) identify the clinical, social, and illness-related factors that predict the likelihood of patients performing physical activity. The global sample consists of 401 patients, with a main psychiatric diagnosis of bipolar disorder (43.4%, N = 174), psychosis spectrum disorder (29.7%; N = 119), or major depression (26.9%; N = 118). 29.4% (N = 119) of patients reported performing physical activity regularly, most frequently walking (52.1%, N = 62), going to the gym (21.8%, N = 26), and running (10.9%, N = 13). Only 15 patients (3.7%) performed at least 75 min of vigorous physical activity per week. 46.8% of patients adopted sealing over as a recovery style and 37.9% used a mixed style toward integration. Recovery style is influenced by gender (p < 0.05) and age (p < 0.05). The probability to practice regular physical activity is higher in patients with metabolic syndrome (Odds Ratio - OR: 2.1; Confidence Interval - CI 95%: 1.2–3.5; p < 0.050), and significantly lower in those with higher levels of anxiety/depressive symptoms (OR: 0.877; CI 95%: 0.771–0.998; p < 0.01). Globally, patients with severe mental disorders report low levels of physical activities, which are associated with poor recovery styles. Psychoeducational interventions aimed at increasing patients' motivation to adopt healthy lifestyle behaviors and modifying recovery styles may improve the physical health of people with severe mental disorders thus reducing the mortality rates.

Background

Recovery is a “process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential”. In patients with severe mental disorders, recovery should represent the final goal of personalized treatment plans for all clinicians (1–3). The recovery styles adopted by patients with severe mental disorders predict their personal and psychosocial functioning as well as their adherence to therapeutic plans. McGlashan et al. (4) described a continuum of recovery styles, from “sealing over”, which is characterized by avoiding the illness experience and is associated with negative long-term outcomes (5), to “integration”, characterized by incorporating the psychotic episode into own identity. The integration style is associated with better long-term outcomes, in terms of adherence to treatments and engagement in psychosocial interventions (6–8).

The full recovery of people with severe mental disorders is hampered by many clinical and socio-demographic factors, including patient's age, pre-morbid level of functioning, educational level, working condition, social network, cognitive schemas (9), severity and type of symptoms, duration of illness, level of insight (10), clinical staging, previous treatments, time to remission, patient's social network, family ties, environmental exposures, presence of physical comorbidities (11, 12). In particular, patients with severe mental disorders have very poor physical health, suffering from coronary heart diseases, diabetes, respiratory, renal, and infectious diseases (13–17). The higher presence of physical illnesses compared to the general population is due to several causes (18, 19), including the adoption of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, such as heavy smoking (20–23), heavy alcohol drinking (24–26), use of illicit drugs (27, 28), unbalanced diet and low levels of physical activity (29).

Physical activity, which is defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure”, and physical exercise, defined as “a subset of physical activity that is planned, structured, and repetitive and has as a final or an intermediate objective the improvement or maintenance of physical fitness” (30), have positive effects on both physical and mental health (31). In fact, people who perform regular physical activity have a reduced risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality.

Interventions increasing the levels of physical activity improve body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness and reduce the cardiometabolic burden and psychiatric symptoms (32). They also improve patients' quality of life, cognition, personal functioning, life skills, and social networks (33–35). Moreover, by improving patients' self-confidence and motivation to change, physical activity is also associated with improvement in the recovery process.

The physical health of patients with severe mental disorders is too often devaluated (36–39). Clinicians worldwide tend to prioritize other (mental) health domains, with the consequence of not motivating enough their patients toward physical activity (40–42). The clinical, biological, and social correlates of physical activity in people with severe mental disorders have been investigated only in a few studies (43, 44). Moreover, studies exploring the relationship between physical activity and recovery styles are also lacking (45).

Appropriate interventions increasing the levels of physical activity of patients with severe mental disorders should be developed (46, 47). Several trials have been promoted with a specific focus on physical activity, including a motivational coaching in order to increase the participation in physical activity programmes of patients with severe mental disorders (48–50).

In this paper, we: (a) describe the levels of physical activity and the recovery styles in patients with severe mental disorders; (b) investigate the clinical, social, and illness-related factors that are associated with the levels of physical activity in patients with severe mental disorders.

Methods

The present paper is based on data collected within the LIFESTYLE trial (51), a national, multicentric, randomized, controlled trial with blinded outcome assessments, coordinated by the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” in Naples and carried out in collaboration with Universities of Bari, Genova, L'Aquila, Pisa, and Rome-Tor Vergata.

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) age between 18 and 65 years; (2) diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, other psychotic disorder, major depressive disorder, or bipolar disorder according to the DSM-5 and confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5); (3) ability to provide written informed consent; (4) BMI ≥ 25; (5) in charge to the local mental health center at least for three months before recruitment.

The main outcome measure considered for this analysis is the level of physical activities. Physical activity has been evaluated with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—short form (52), which is a 18-item questionnaire exploring physical activity in terms of walking, moderate-intensity, and vigorous-intensity physical activities.

The 24-items Questionnaire on lifestyle behaviors, developed by the Italian National Institute of Health, has been used to explore patients' dietary patterns (e.g., food eaten at lunch or dinner), smoking habits (e.g., number of cigarettes smoked per day; attempts to quit smoking), and physical activity (e.g., time spent in walking per day) (53).

Recovery styles have been evaluated with the Recovery Style Questionnaire (RSQ) (54), a 39-item self-report assessment instrument exploring six styles of adaptation to severe mental disorder and recovery: “sealing over”, “tends toward sealing over”, “mixed picture in which sealing over predominates”, “mixed picture in which integration predominates”, “tends toward integration”, and “integration”.

Other assessment tools include the Food Frequency Questionnaire - short version (55); the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (56); the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (57); the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ) (58); the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) (59); the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) (60); the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (61); the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB)—brief version (62, 63); the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) (64); ad-hoc questionnaire on sexual health; the Pattern of Care Schedule (PCS)—modified version (51).

Information on weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, resting heart rate, HDL, LDL and overall levels of cholesterol, blood glucose, triglycerides, and blood insulin have been collected by the researcher with the Anthropometric schedule. The homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index and the Framingham Risk Score have been calculated for quantifying insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk, respectively.

Patients' psychopathological status has been assessed with the 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (65). Patients' social functioning has been explored through the Personal and Social Performance Scale (66), a 100-point single-item rating scale, subdivided into four main areas: (1) “socially useful activities”; (2) “personal and social relationships”; (3) “self-care”; and (4) “disturbing and aggressive behaviors”.

This study was conducted in accordance with globally accepted standards of good practice, in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and with local regulations. The study protocol was formally approved by the Ethics Committee of the Coordinating Center in January 2017 (Approval Number: 64). All other methodological details of the LIFESTYLE study are reported in (51) and the trial registration number is the following: 2015C7374S.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and frequency tables have been used to assess patients' socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. Chi-square with multiple comparisons and ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections have been adopted to detect differences in the levels of physical activities. Bivariate analyses have been performed in order to evaluate the association between the levels of physical activities, the recovery styles, and the severity of clinical symptoms.

Multivariate logistic regression models have been implemented to identify predictors of practicing physical activity. The models have been adjusted for several socio-demographic characteristics, including gender, age, presence of physical illness, being married, level of education, satisfaction with one's own life, adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies, duration of illness, and recovery styles. This statistical approach has been already adopted in previous published papers based on the LIFESTYLE trial (51, 67, 68) and the categorical variable “Center” was also entered in the regression model.

A multiple imputation approach has been used for managing missing data. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 and statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26.0, and STATA, version 15.

Results

Patients' Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The final sample consists of 401 patients, mostly female (57.1%, N = 229) and with a mean age of 45.6 (±11.8) years. Patients are affected by bipolar disorder (43.4%, N = 174), psychosis spectrum disorder (29.7%; N = 119), or major depression (26.9%; N = 118); the duration of the illness is about 15.6 (±11.3) years.

Most patients present mild symptoms at the BPRS and have a discrete level of personal functioning (PSP value: 65.7 ± 15.1).

Most patients are either overweight (35.4%; N = 142; BMI ranging between 25–29.9) or obese (34.9%; N = 140), with a mean BMI of 32.2 (±5.5). 40.6% of patients are heavy smokers and 67.8% drink alcohol more than three times per week. 53.4% of patients (N = 214) suffer from the metabolic syndrome; in particular, 56.6% (N = 227) have systolic hypertension, 36.1% (N = 143) diastolic hypertension and 26.9% (N = 108) hyperglycaemia.

As regards diet habits, 31.0% of patients eat less than two portions of fruits per week and 37.6% less than two portions of vegetables per week. 43.5% of the sample drink about one liter of water per day, below the WHO recommended threshold of more than two liters/day (Table 1).

Recovery Styles and Levels of Physical Activity

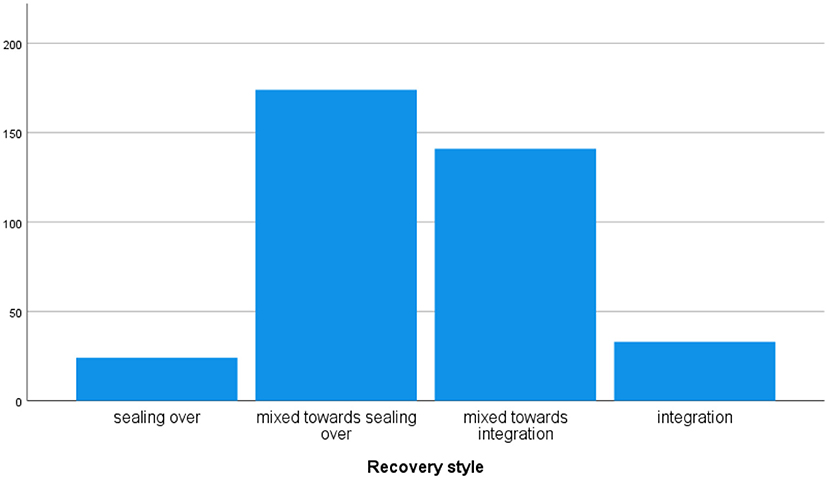

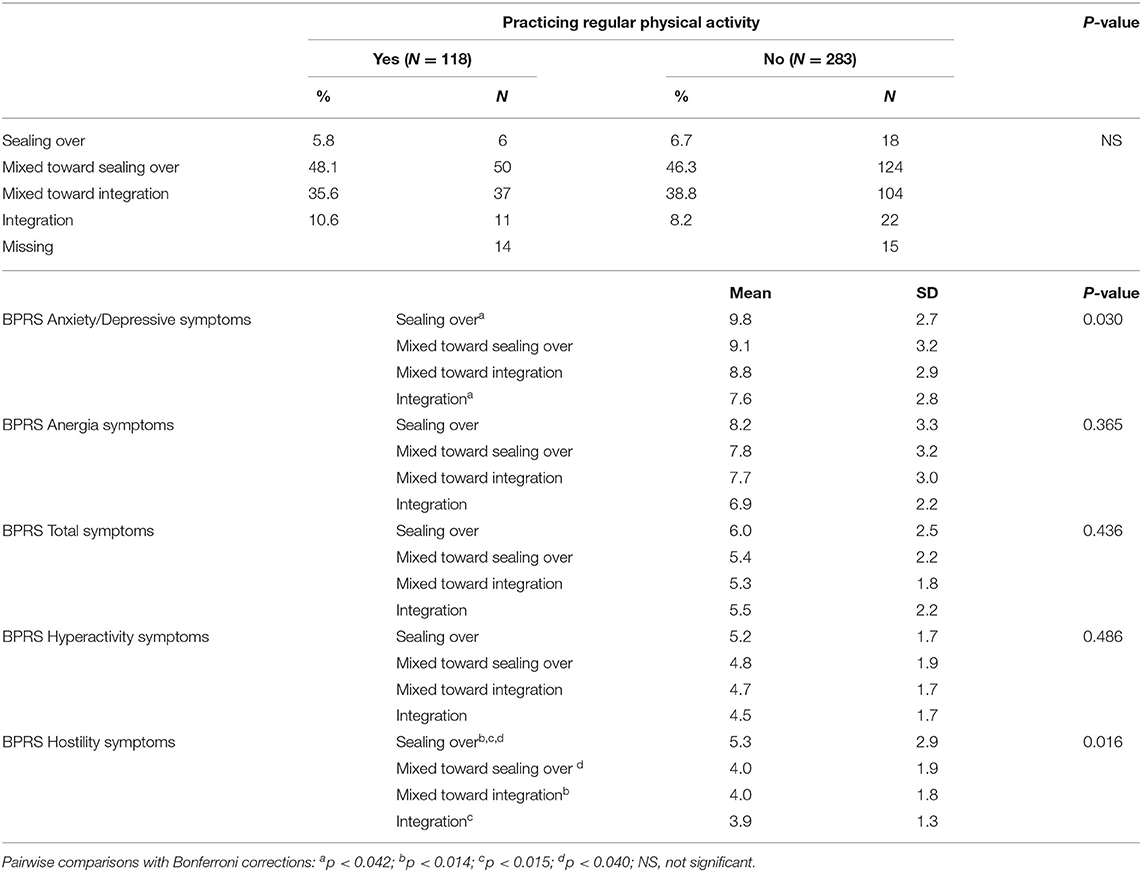

The “sealing over” recovery style is adopted by 46.8% of patients (N = 174), a “mixed style” is used by 37.9% of patients (N = 141), and “integration” is used by 8.9% of patients (N = 33) only (Figure 1). Recovery styles vary according to gender (p < 0.05) and age (p < 0.05), while there are no differences according to the diagnostic category. Patients adopting “integration” have lower levels of anxiety/depressive and hostility symptoms compared to those using “sealing over” (p < 0.030 and p < 0.050, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2. Differences in recovery styles according to practicing regular physical activity and to symptoms' severity.

Regular physical activity is performed by 29.4% (N = 119) of patients. The most frequent physical activities performed by patients are walking (52.1%, N = 62), going to the gym (21.8%, N = 26), running (10.9%, N = 13), playing football (7.6%, N = 9), cycling (9.2%, N = 11), and swimming (2.5%, N = 3). Physical activities' preferences are not influenced by body mass index, age, and duration of illness. Only playing football is preferred by male patients (p < 0.001).

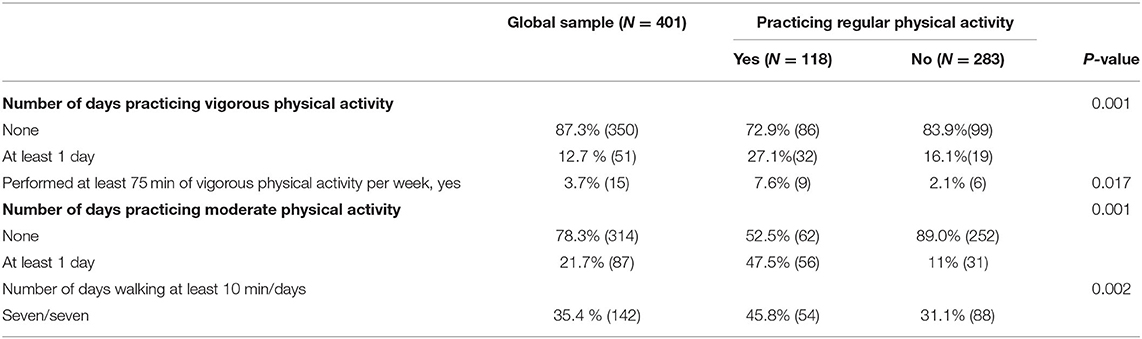

Vigorous physical activity performed for at least 75 min per week is done by 15 patients (3.7%), while moderate physical activity by 21.7% of patients (Table 3).

Patients performing regular physical activities have lower levels of anergia (7.0 ± 3.2 vs. 8.1 ± 2.8, p < 0.001) and hostility (4.2 ± 1.9 vs. 3.7 ± 1.5, p < 0.001) at the BPRS compared with those not practicing physical activities; no other significant clinical differences exist in the other clinical domains between the two groups. Patients practicing physical activity report higher levels of perceived satisfaction with the quality of life compared with non-active patients (4.3 ± 0.9 vs. 3.9 ± 1.1, p < 0.005). There are no differences in the levels of personal functioning, internalized stigma, treatment adherence, and cognitive functioning. The levels of physical activity do not differ according to the condition of being smokers or being alcohol drinkers (Table 1). No differences were found between those patients practicing regular physical activities and those not practicing it in the recovery styles.

Multivariate Analyses

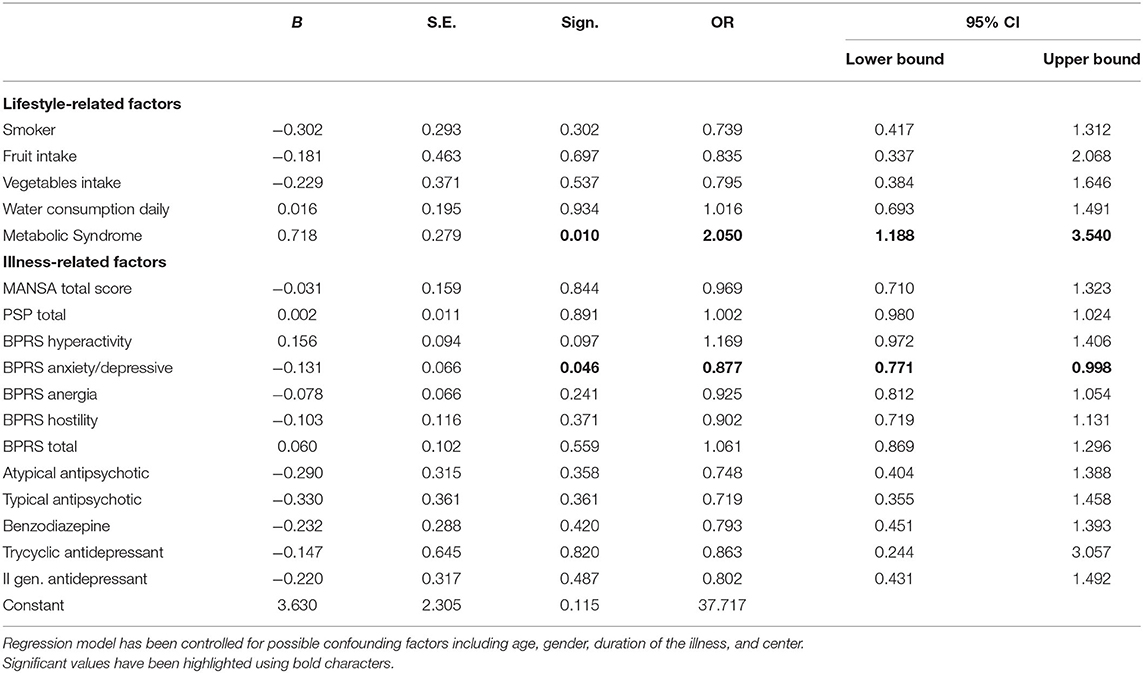

According to the multivariate logistic regression models, patients with metabolic syndrome have a higher probability to practice regular physical activity (OR: 2.1; CI 95%: 1.2–3.5; p < 0.050). Patients with higher levels of anxiety/depressive symptoms (OR: 0.877; CI 95%: 0.771–0.998; p < 0.01) have a significantly lower tendency to practice physical activity. The likelihood of practicing regular physical activity is not influenced by other lifestyle variables, including diet, smoking, or drinking water, as well as other illness-related variables, such as duration of illness, pharmacological treatment, and recovery style (Table 4).

Discussion

Recovery from severe mental illness is a complex and multifaceted process, which represents the ultimate goal of a treatment plan for patients affected by different mental disorders. The adoption of different recovery styles by patients influences their personal and psychosocial functioning, therapeutic adherence, and treatments' engagement.

In our sample, the majority of recruited patients use a “sealing over” recovery style, which is associated with a negative long-term outcome (4). In fact, “sealing over” patients have an insecure identity (7), report negative experiences in early attachment, have social difficulties, and are affected by predominant negative symptoms. On the contrary, people adopting an “integration” style (i.e., incorporating the psychotic episode into their identity), report more favorable long-term outcomes in terms of engagement with services and perceived quality of life (69–71). A recent study carried out in Italy found that the integration style is associated with a good functional outcome, through acceptance of the psychotic experience and the awareness of the need for support and care, while patients adopting sealing over were less likely to maintain their social role and to invest in interpersonal relationships, with a global poorer long-term outcome (6). Unfortunately, in our study, only a minority of patients adopt this recovery style.

The present study is focused on recovery styles and the association with the levels of physical activities. In fact, recovery styles influence treatment engagement and illness status (45), as also the propensity to perform physical activities. On the other hand, physical activity can promote recovery by improving patients' self-confidence, health status, and motivation to change. In our sample, patients reported low levels of physical activities and low levels of recovery (characterized by a prevalence of sealing over style), confirming the bidirectional relationship between recovery and physical activity. It would be interesting to explore the effects of a physical activity intervention on the levels of recovery styles of patients with severe mental disorders in a longitudinal study.

A significant obstacle to recovery in people with severe mental disorders is represented by the high rate of physical comorbidities and the reduced life expectancy compared with the general population (72–76). Several factors contribute to the higher mortality and morbidity in patient with severe mental disorders, such as the higher prevalence rate of metabolic syndrome compared to the general population (77, 78) and the adoption of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (79). In fact, patients with severe mental disorders are frequently physically inactive, not fulfilling the WHO recommendations (80, 81). Our findings confirm the low levels of physical activity in patients with severe mental disorders (29), with only one patient out of three reporting to perform any type of physical activity. Moreover, when considering the type of physical activity, only 3.7% of patients performed at least 75 min of vigorous physical activity per week, which is the WHO recommended threshold for having a beneficial impact on physical health. It may be that people do not even know what is considered “regular physical activity” (82), suggesting the need to develop and carry out informative interventions tailored to the general population and people with severe mental disorders. Within the LIFESTYLE project, our research team has developed a psychoeducational lifestyle group intervention for people with severe mental disorders (51), whose efficacy in the improvement of healthy lifestyle behaviors has been documented in a randomized controlled trial (67, 68).

The various socio-demographic variables considered did not influence the choice of any specific physical activity, differently from data collected in the general population (83). This finding confirms that it is not possible to simply translate the strategies developed for the general population to increase physical activities to people with severe mental disorders, but that more specific and targeted interventions are needed (84, 85).

In our regression models, lifestyle- and illness-related factors have been tested as possible predictors of practicing regular physical activity. The presence of the metabolic syndrome was the only lifestyle factor significantly predicting the likelihood of patients practicing physical activity, even after controlling for age, gender, duration of illness, and pharmacological treatments. Other lifestyle factors, such as diet or smoking, do not have any impact on the outcome. It may be that patients with severe mental disorders are reluctant to practice physical activities regularly and tend to do so only as a “last resort” when they are diagnosed with severe physical disturbances, such as hypertension or obesity, which are core elements of the metabolic syndrome. This finding suggests the need the improve regular physical check-up visits for patients with severe mental disorders, who are instead treated with reluctance by other physicians (86, 87). Studies including not only overweight patients may further confirm this hypothesis and explore the role of “trait” factors such as affective temperaments, personality traits, or cognitive styles on the propensity to practice regular physical activity in patients with severe mental disorders.

The following limitations of the study are hereby acknowledged. First, the inclusion of overweight patients only, which limits the generalizability of our findings to patients with different metabolic profiles. Second, the recruitment of a mixed sample of patients with severe mental disorders, which may have reduced the effect related to the diagnostic category. Third, the relatively low sample size, which does not allow us to draw firm conclusions about our findings.

In conclusion, our findings confirm that patients with severe mental disorders are sedentary and perform any type of physical activity only rarely. The recovery of patients with severe mental disorders is related to the adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviors (88–92).

Strategies aimed at increasing the levels of physical activity in patients with severe mental disorders may improve physical and mental outcomes and reduce the mortality rate. A possible way forward to improve practicing of physical activities in patients with severe mental disorders should include a specific motivational coaching on the role of exercise intervention and a personalized, patient-centered approach tailored to the needs of each individual patient.

Data Availability Statement

Data published in this paper is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical Committee University of Campania L. Vanvitelli. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Working Group Lifestyle

Vincenzo Giallonardo, Valeria Del Vecchio, Arcangelo Di Cerbo, Carlotta Brandi, Luigi Marone, Bianca Della Rocca, Department of Psychiatry, University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli”; Linda Antonella Antonucci, Giuseppe Blasi, Laura De Mastro, Francesco Massari, Giulio Pergola, Alessandra Raio, Antonio Rampino, Marianna Russo, Pierluigi Selvaggi, Angelantonio Tavella, Alessandro Bertolino, University of Bari; Alice Trabucco, University of Genoa; Ramona di Stefano, Paolo Stratta, Department of Mental Health, L'Aquila; Virginia Pedrinelli, Carlo Antonio Bertelloni, Annalisa Cordone, University of Pisa; Emanuela Bianciardi, Cinzia Niolu, University of Rome Tor Vergata.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research within the framework of the Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) – year 2015 (Grant Number: 2015C7374S).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Maj M, Stein DJ, Parker G, Zimmerman M, Fava GA, De Hert M, et al. The clinical characterization of the adult patient with depression aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:269–93. doi: 10.1002/wps.20771

2. Maj M, van Os J, De Hert M, Gaebel W, Galderisi S, Green MF, et al. The clinical characterization of the patient with primary psychosis aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry. (2021) 20:4–33. doi: 10.1002/wps.20809

3. Fava GA, Guidi J. The pursuit of euthymia. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:40–50. doi: 10.1002/wps.20698

4. McGlashan TH, Levy ST, Carpenter WT Jr. Integration and sealing over. Clinically distinct recovery styles from schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1975) 32:1269–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760280067006

5. Gruber M, Rumpold T, Schrank B, Sibitz I, Otzelberger B, Jahn R, et al. Recover recovery style from psychosis: a psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Recovery Style Questionnaire (RSQ). Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2018) 29:e4. doi: 10.1017/S2045796018000471

6. Zizolfi D, Poloni N, Caselli I, Ielmini M, Lucca G, Diurni M, et al. Resilience and recovery style: a retrospective study on associations among personal resources, symptoms, neurocognition, quality of life and psychosocial functioning in psychotic patients. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2019) 12:385–95. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S205424

7. Tait L, Birchwood M, Trower P. Adapting to the challenge of psychosis: personal resilience and the use of sealing-over (avoidant) coping strategies. Br J Psychiatr. (2004) 185:410–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.5.410

8. Lysaker PH, Hasson-Ohayon I. Metacognition in psychosis: a renewed path to understanding of core disturbances and recovery-oriented treatment. World Psychiatry. (2021) 20:359–61. doi: 10.1002/wps.20914

9. Moritz S, Silverstein SM, Dietrichkeit M, Gallinat J. Neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia are likely to be less severe and less related to the disorder than previously thought. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:254–5. doi: 10.1002/wps.20759

10. Slade M, Sweeney A. Rethinking the concept of insight. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:389–90. doi: 10.1002/wps.20783

11. Kim H, Turiano NA, Forbes MK, Kotov R, Krueger RF, Eaton NR, et al. Internalizing psychopathology and all-cause mortality: a comparison of transdiagnostic vs. diagnosis-based risk prediction. World Psychiatry. (2021) 20:276–82. doi: 10.1002/wps.20859

12. Menon V. Brain networks and cognitive impairment in psychiatric disorders. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:309–10. doi: 10.1002/wps.20799

13. Liu NH, Daumit GL, Dua T, Aquila R, Charlson F, Cuijpers P, et al. Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:30–40. doi: 10.1002/wps.20384

14. Nielsen RE, Banner J, Jensen SE. Cardiovascular disease in patients with severe mental illness. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2021) 18:136–45. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-00463-7

15. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Mitchell AJ. The prevalence and predictors of type two diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2015) 132:144–57. doi: 10.1111/acps.12439

16. Uju Y, Kanzaki T, Yamasaki Y, Kondo T, Nanasawa H, Takeuchi Y, et al. A cross-sectional study on metabolic similarities and differences between inpatients with schizophrenia and those with mood disorders. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2020) 19:53. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00303-5

17. Oude Voshaar RC, Aprahamian I, Borges MK, van den Brink RHS, Marijnissen RM, Hoogendijk EO, et al. Excess mortality in depressive and anxiety disorders: The Lifelines Cohort Study. Eur Psychiatry. (2021) 64:e54. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2229

18. Taipale H, Tanskanen A. Meht?l? J,Vattulainen P, Correll CU, Tiihonen J. 20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:61–68. doi: 10.1002/wps.20699

19. Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson J, Maj M, Sartorius N. Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2007) 116:317–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01095.x

20. Chesney E, Robson D, Patel R, Shetty H, Richardson S, Chang CK, et al. The impact of cigarette smoking on life expectancy in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar affective disorder: An electronic case register cohort study. Schizophr Res. (2021) 238:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.09.006

21. Estrada E, Hartz SM, Tran J, Hilty DM, Sklar P, Smoller JW, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychosis in Bipolar disorder and Schizoaffective disorder, Bipolar type. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. (2016) 171:521–4. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32385

22. Ringin E, Cropley V, Zalesky A, Bruggemann J, Sundram S, Weickert CS, et al. The impact of smoking status on cognition and brain morphology in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychol Med. (2021) 14:1–19. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005152

23. Zangen A, Moshe H, Martinez D, Barnea-Ygael N, Vapnik T, Bystritsky A, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for smoking cessation: a pivotal multicenter double-blind randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry. (2021) 20:397–404. doi: 10.1002/wps.20905

24. Squeglia LM. Alcohol and the developing adolescent brain. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:393–4. doi: 10.1002/wps.20786

25. Listabarth S, Vyssoki B, Waldhoer T, Gmeiner A, Vyssoki S, Wippel A, et al. Hazardous alcohol consumption among older adults: A comprehensive and multi-national analysis of predictive factors in 13,351 individuals. Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 64:e4. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.112

26. Drake RE, Xie H. McHugo GJ. A 16-year follow-up of patients with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:397–8. doi: 10.1002/wps.20793

27. Volkow ND, Torrens M, Poznyak V. Managing dual disorders: a statement by the Informal Scientific Network UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:396–7. doi: 10.1002/wps.20796

28. Sánchez-Gutiérrez T, Fernandez-Castilla B, Barbeito S, González-Pinto A, Becerra-García JA, Calvo A. Cannabis use and nonuse in patients with first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing neurocognitive functioning. Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 63:e6. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2019.9

29. Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Mugisha J, Hallgren M, et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:308–15. doi: 10.1002/wps.20458

30. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. (1985) 100:126–31.

31. Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet. (2016) 388:1302–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30370-1

32. Kandola A, Ashdown-Franks G, Stubbs B, Osborn DPJ, Hayes JF. The association between cardiorespiratory fitness and the incidence of common mental health disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2019) 257:748–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.088

33. Brooke LE, Lin A, Ntoumanis N, Gucciardi DF. Is sport an untapped resource for recovery from first episode psychosis? A narrative review and call to action. Early Interv Psychiatry. (2019) 13:358–68. doi: 10.1111/eip.12720

34. Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, Vancampfort D, Schunch FB, Hoare E, et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:360–80. doi: 10.1002/wps.20773

35. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, Firth J, Veronese N, Solmi M. EPA guidance on physical activity as a treatment for severe mental illness: a meta-review of the evidence and position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). Eur Psychiatry. (2018) 54:124–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.004

36. Ayerbe L, Forgnone I, Foguet-Boreu Q, González E, Addo J, Ayis S. Disparities in the management of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2018) 48:2693–701. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718000302

37. Björk Brämberg E, Torgerson J, Norman Kjellström A, Welin P, Rusner M. Access to primary and specialized somatic health care for persons with severe mental illness: a qualitative study of perceived barriers and facilitators in Swedish health care. BMC Fam Pract. (2018) 19:12. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0687-0

38. Chew-Graham CA, Gilbody S, Curtis J, Holt RI, Taylor AK, Shiers D. Still 'being bothered about Billy': managing the physical health of people with severe mental illness. Br J Gen Pract. (2021) 71:373–6. doi: 10.3399/bjgp21X716741

39. Lerbæk B, Jørgensen R, Aagaard J, Nordgaard J, Buus N. Mental health care professionals' accounts of actions and responsibilities related to managing physical health among people with severe mental illness. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2019) 33:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.11.006

40. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D. Physical activity, exercise, and mental disorders: it is time to move on. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. (2021) 43:177–84. doi: 10.47626/2237-6089-2021-0237

41. Correll CU, Sikich L, Reeves G. Metformin add-on vs. antipsychotic switch vs continued antipsychotic treatment plus healthy lifestyle education in overweight or obese youth with severe mental illness: results from the IMPACT trial. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:69–80. doi: 10.1002/wps.20714

42. Robson D, Haddad M, Gray R, Gournay K. Mental health nursing and physical health care: A cross-sectional study of nurses' attitudes, practice, and perceived training needs for the physical health care of people with severe mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2013) 22:409–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00883.x

43. Mishu MP, Peckham EJ, Heron PN, Tew GA, Stubbs B, Gilbody S. Factors associated with regular physical activity participation among people with severe mental ill health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2019) 54:887–95. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1639-2

44. Buhagiar K, Templeton G, Osborn DPJ. Recent physical conditions and health service utilization in people with common mental disorders and severe mental illness in England: Comparative cross-sectional data from a nationally representative sample. Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 63:e19. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.22

45. Tait L, Birchwood M, Trower P. Predicting engagement with services for psychosis: insight, symptoms and recovery style. Br J Psychiatry. (2003) 182:123–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.123

46. De Rosa C, Sampogna G, Luciano M, et al. Improving physical health of patients with severe mental disorders: a critical review of lifestyle psychosocial interventions. Expert Rev Neurother. (2017) 17:667–81. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2017.1325321

47. Fiorillo A, Luciano M, Pompili M, Sartorius N. Editorial: reducing the mortality gap in people with severe mental disorders: the role of lifestyle psychosocial. Interventions Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:434. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00434

48. Suen YN, Lo LHL, Lee EH, Hui CL, Chan SKW, Chang WC, et al. Motivational coaching augmentation of exercise intervention for early psychotic disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2021) 27:48674211061496. doi: 10.1177/00048674211061496

49. Rosenbaum S, Lederman O, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Stanton R, Ward PB. How can we increase physical activity and exercise among youth experiencing first-episode psychosis? A systematic review of intervention variables. Early Interv Psychiatry. (2016) 10:435–40. doi: 10.1111/eip.12238

50. Speyer H, Christian Brix Nørgaard H, Birk M, Karlsen M, Storch Jakobsen A, Pedersen K, et al. The CHANGE trial: no superiority of lifestyle coaching plus care coordination plus treatment as usual compared to treatment as usual alone in reducing risk of cardiovascular disease in adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and abdominal obesity. World Psychiatry. (2016) 15:155–65. doi: 10.1002/wps.20318

51. Sampogna G, Fiorillo A, Luciano M, Del Vecchio V, Steardo LJr, Pocai B, et al. A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of a psychosocial behavioral intervention to improve the lifestyle of patients with severe mental disorders: study protocol. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:235. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00235

52. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2003) 35:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

53. Istituto Superiore di Sanità Osservatorio Fumo Alcol e Droga – OSSFAD. Questionario di valutazione degli stili di vita.

54. Drayton M, Birchwood M, Trower P. Early attachment experience and recovery from psychosis. Br J Clin Psychol. (1998) 37:269–84.

55. Marventano S, Mistretta A, Platania A, Galvano F, Grosso G. Reliability and relative validity of a food frequency questionnaire for Italian adults living in Sicily, Southern Italy. Int J Food Sci Nutr. (2016) 67:857–64. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2016.1198893

56. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. (1991) 86:1119–27.

57. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

58. Raistrick D, Bradshaw J, Tober G, Weiner J, Allison J, Healey C. Development of the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ): a questionnaire to measure alcohol and opiate dependence in the context of a treatment evaluation package. Addiction. (1994) 89:563–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03332.x

59. Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. (1986) 24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007

60. Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. (1968) 16:622–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x

61. Priebe S, Huxley P, Knight S, Evans S. Application and results of the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA). Int J Soc Psychiatry. (1999) 45:7–12. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500102

62. Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. (2008) 165:203–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042

63. Kern RS, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 2: co-norming and standardization. Am J Psychiatry. (2008) 165:214–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010043

64. Ritsher J, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measures. Psychiatry Res. (2003) 121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008

65. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura JA. Manual for expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Schizophre Bull. (1986) 12:594–602.

66. Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2000) 101:323–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2000.tb10933.x

67. Luciano M, Sampogna G, Del Vecchio V, Giallonardo V, Palummo C, Andriola I, et al. The impact of clinical and social factors on the physical health of people with severe mental illness: results from an Italian multicentre study. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 303:114073. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114073

68. Luciano M, Sampogna G, Amore M, Andriola I, Calcagno P, Carmassi C, et al. How to improve the physical health of people with severe mental illness? A multicentric randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of a lifestyle group intervention. Eur Psychiatry. (2021) 64:e72. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2253

69. Espinosa R, Valiente C, Rigabert A, Song H. Recovery style and stigma in psychosis: the healing power of integrating. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. (2016) 21:146–55. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2016.1147427

70. Vender S, Poloni N, Aletti F, Bonalumi C, Callegari C. Service engagement: psychopathology, recovery style and treatments. Psychiatry J. (2014) 2014:249852. doi: 10.1155/2014/249852

71. Feldman R. What is resilience: an affiliative neuroscience approach. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:132–50. doi: 10.1002/wps.20729

72. Fiorillo A, Sartorius N. Mortality gap and physical comorbidity of people with severe mental disorders: the public health scandal. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2021) 20:52. doi: 10.1186/s12991-021-00374-y

73. Filipčić I, Šimunović G. Patterns of chronic physical multimorbidity in psychiatric and general population. J Psychosom Res. (2018) 114:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.011

74. Thornicroft G. Physical health disparities and mental illness: the scandal of premature mortality. Br J Psychiatry. (2011) 199:441–2. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092718

75. Carrà G, Bartoli F, Carretta D, Crocamo C, Bozzetti A, Clerici M, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in people with severe mental illness: a mediation analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2014) 49:1739–46. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0835-y

76. De Leon J, Sanz EJ, Norén GN, De Las Cuevas C. Pneumonia may be more frequent and have more fatal outcomes with clozapine than with other second-generation antipsychotics. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:120–1. doi: 10.1002/wps.20707

77. Bartoli F, Carrà G, Crocamo C, Carretta D, Clerici M. Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and metabolic syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. (2013) 170:927–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040447

78. McGlashan T, Levy ST. Sealing-over in a Therapeutic Community. Psychiatry. (2019) 82:1–12. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2019.1594437

79. Plana-Ripoll O, Musliner KL, Dalsgaard S. Nature and prevalence of combinations of mental disorders and their association with excess mortality in a population-based cohort study. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:339–49. doi: 10.1002/wps.20802

80. World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

81. World Health Organization. (2013). Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. Geneva: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

82. Jayasinghe UW, Harris MF, Parker SM, Litt J, van Driel M, Mazza D, et al. Preventive Evidence into Practice (PEP) Partnership Group. The impact of health literacy and life style risk factors on health-related quality of life of Australian patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2016) 14:68. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0471-1

83. Eime RM, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Nelson R. Demographic characteristics and type/frequency of physical activity participation in a large sample of 21,603 Australian people. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:692. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5608-1

84. Kirschner V, Lamp N, Dinc Ü, Becker T, Kilian R, Mueller-Stierlin AS. The evaluation of a physical health promotion intervention for people with severe mental illness receiving community based accommodational support: a mixed-method pilot study. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:6. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03640-1

85. De Rosa C, Sampogna G, Luciano M, Del Vecchio V, Fabrazzo M, Fiorillo A, et al. Social versus biological psychiatry: It's time for integration! Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2018) 64:617–21. doi: 10.1177/0020764017752969

86. Butler J, de Cassan S, Turner P, Lennox B, Hayward G, Glogowska M, et al. Attitudes to physical healthcare in severe mental illness; a patient and mental health clinician qualitative interview study. BMC Fam Pract. (2020) 21:243. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01316-5

87. Fabrazzo M, Monteleone P, Prisco V, Perris F, Catapano F, Tortorella A, et al. Olanzapine is faster than haloperidol in inducing metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenic and bipolar patients. Neuropsychobiology. (2015) 72:29–36. doi: 10.1159/000437430

88. McEwen BS. The untapped power of allostasis promoted by healthy lifestyles. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:57–8. doi: 10.1002/wps.20720

89. Pereira L, Budovich A, Claudio-Saez M. Monitoring of metabolic adverse effects associated with atypical antipsychotics use in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. J Pharm Pract. (2019) 32:388–93. doi: 10.1177/0897190017752712

90. Rüther T, Bobes J, De Hert M, Svensson TH, Mann K, Batra A, et al. EPA guidance on tobacco dependence and strategies for smoking cessation in people with mental illness. Eur Psychiatry. (2014) 29:65–82. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.11.002

91. Stanton R, Reaburn P, Happell B. Barriers to exercise prescription and participation in people with mental illness: the perspectives of nurses working in mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 22:440–8. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12205

Keywords: lifestyle, physical activity, sedentary behaviors, mortality, severe mental disorders

Citation: Sampogna G, Luciano M, Di Vincenzo M, Andriola I, D'Ambrosio E, Amore M, Serafini G, Rossi A, Carmassi C, Dell'Osso L, Di Lorenzo G, Siracusano A, Rossi R, Fiorillo A and Working Group LIFESTYLE (2022) The Complex Interplay Between Physical Activity and Recovery Styles in Patients With Severe Mental Disorders in a Real-World Multicentric Study. Front. Psychiatry 13:945650. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.945650

Received: 16 May 2022; Accepted: 31 May 2022;

Published: 11 July 2022.

Edited by:

Laura Orsolini, Marche Polytechnic University, ItalyReviewed by:

Giuseppe Carrà, University of Milano-Bicocca, ItalyCaterina Adele Viganò, University of Milan, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Sampogna, Luciano, Di Vincenzo, Andriola, D'Ambrosio, Amore, Serafini, Rossi, Carmassi, Dell'Osso, Di Lorenzo, Siracusano, Rossi, Fiorillo and Working Group LIFESTYLE. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gaia Sampogna, Z2FpYS5zYW1wb2duYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Gaia Sampogna

Gaia Sampogna Mario Luciano

Mario Luciano Matteo Di Vincenzo

Matteo Di Vincenzo Ileana Andriola

Ileana Andriola Enrico D'Ambrosio

Enrico D'Ambrosio Mario Amore

Mario Amore Gianluca Serafini

Gianluca Serafini Alessandro Rossi

Alessandro Rossi Claudia Carmassi

Claudia Carmassi Liliana Dell'Osso5

Liliana Dell'Osso5 Giorgio Di Lorenzo

Giorgio Di Lorenzo Alberto Siracusano

Alberto Siracusano Rodolfo Rossi

Rodolfo Rossi Andrea Fiorillo

Andrea Fiorillo