- 1Psychiatry Department, Medical School, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Psychology Department, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

Introduction: Afghanistan's domestic upheaval following the Taliban's invasion leads to massive displacement of its population. The number of Afghan refugees in Iran has dramatically increased since the Taliban's takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021. Multiple pre-and post-migratory traumatic experiences affect immigrants' physical, psychological, social, and economic wellbeing. The coronavirus outbreak, considered a traumatic experience in human life in the 21st century, added to their problems in Iran and exposed them to new challenges. This qualitative study aimed to investigate their experiences early before, during, and after immigration and the pandemic's challenges to their lives in Iran.

Methods: In the present qualitative study, ten Afghan residents living in Iran who immigrated to Iran legally or illegally since the summer of 2021 and the last year after the second Taliban invasion were selected via purposive sampling. A semi-structured interview was applied to gather the data, and the data were analyzed through Braun and Clarke's thematic analysis method.

Results: Ten male participants with a mean age of 26 y/o were interviewed. Their residence in Iran was between 20 days and 8 months. Four main themes were extracted. The first theme, the Tsunami of suffering, represents a disruption of the normal flow of life. Six subthemes, including loss, being near death, insecurity, sudden hopelessness, leaving the country involuntarily, and reluctance to explore underlying emotions, are included in this category. The second one, Lost in space, describes the participant's attempt to leave Afghanistan following the extensive losses and violent death threats. Their experiences are categorized into four subthemes: the miserable trip, encountering death, life-threatening experiences, and being physically and verbally abused. The third theme, with its five subthemes, try to demonstrate the participants' experiences after getting to their destination in Iran. The last one, Challenges of the COVID-19 explained the experience of Taliban return, war trauma, running away, and living as a refugee or immigrant coincided with the COVID pandemic.

Discussion: Our interviewees explained multiple and successive traumatic experiences of war, migration, and the pandemic. The central clinical features of survivors are fears of losing control, being overwhelmed, and inability to cope. They felt abandoned because not only lost their family support in their homeland but could not also receive support in Iran due to the pandemic-related social distancing and isolation. They were dissociated and emotionally numb when describing their experience, which is a hallmark of experiencing severe, unprocessed traumas.

Conclusion: Gaining a better understanding of Afghan refugees lived experiences may help provide them with better social and health care support. Proper mental and physical healthcare support and de-stigmatization programs may reduce the impact of multiple traumas on their wellbeing.

Introduction

Taliban emerged in Afghanistan in the mid-1990s following the withdrawal of Soviet troops, the collapse of Afghanistan's communist regime, and the subsequent breakdown in civil order. This domestic upheaval leads to massive displacement of its population (1). Afghan refugees comprise the largest refugee population in the world (2). The number of Afghan refugees in Iran has dramatically increased since the Taliban's takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021. About five thousand people arrive daily after the takeover, compared to two thousand people beforehand (3). Iran and Pakistan have been the primary host of Afghan refugees for over three decades (1). According to the most recent numbers from October 2020, 2,250,000 undocumented Afghans live in Iran out of 3,636,000. At the same time, 586,000 Afghans have passports, including those on student and extended family visas. Additionally, 780,000 Afghans are refugees (3).

Migration can be a psychological and physical trauma, mainly when it occurs forcefully and involuntarily. People flee to save their lives. It is inevitable, unavoidable, and is not their choice. Multiple pre-migratory stressors such as war, violence, insecurity, torture, murder, homelessness, and starvation force them to leave their home country (4–6). They are looking for a place where they could have opportunities to experience a peaceful and safe present and possible future (7). This unsafe and involuntary migration affects immigrants' physical, psychological, social, and economic wellbeing (8).

It is optimistic if we think it is the end of their miseries. There was frequent physical and psychological trauma along the way, and they experienced many difficulties in the host country (4). After migration, new problems would emerge once they arrive in the new place, and they should struggle with finding work, accommodation, stigmatization, health issues, and multiple losses (2, 6). Because of all these pre-and post-migratory traumatic experiences, they are vulnerable to developing severe mental disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders (2, 9).

The coronavirus outbreak is also a traumatic experience in human life in the 21st century. It seriously impacts mental and physical health, economic and social conditions, and it has revealed that the human being is biologically vulnerable and fragile (10). COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China, in Dec 2019, then spread rapidly to other countries (11). on February 19, 2020, the first cases of Covid-19 were reported in Iran (12). Until March 25, 2022, the disease has infected 7,145,877 people in Iran, and unfortunately, 139,865 of them have died (13).

The disease's unclear and unpredictable nature, the pandemic's unknown end time, and the seriousness of the condition were the major concerns that produced anxiety and disappointment. Social and interpersonal communication has been restricted, and family conflicts have increased due to home quarantines (12).

Refugees are a highly vulnerable subgroup of the population and are at higher risk in the pandemic (14). COVID-19 added to Afghans problems in Iran and exposed them to new challenges (15), Such as poor socioeconomic conditions and accessibility to health care services (14). While the importance of family support to psychological wellbeing is undeniable, Afghan immigrants have also lost this support system through forced relocation, disrupting tight family bonds and socialization during the pandemic (2).

There is not much research available to address this specific issue of an Afghan refugee living in Iran during the Taliban invasion and the pandemic. In this qualitative study, we explored their lived experience early before, during, and after the immigration and the pandemic's challenges to their lives.

Methods

In this qualitative research, the study population included Afghan residents living legally or illegally in Iran who have immigrated to Iran legally or illegally since the summer of 2021 and during the last year after the second Taliban invasion. We selected the participants via the purposive sampling method, which continued until data saturation. The inclusion criteria consisted of age (at least 18 years old), fluency in the Persian language, having at least a high school diploma, no current drug abuse (not in the period of withdrawal or intoxication), and voluntarily acceptance to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were a history of serious medical diseases such as cancer, diabetes and heart disease, the history of psychiatry and neurological disorders that interfered with the interview. At the beginning of the interview, we asked about the exclusion criteria.

The primary data collection tool was the semi-structured interview with participants. First, the interview guide was prepared, and then the text of the questions was read by several experienced experts. Questions were designed to be open-ended with a focus on the topic in the form of an interview guide. The interview guide ensured that the same information was obtained from all participants.

Initially, Afghan immigrants who wished to share their experiences with the researchers were selected among the available individuals regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Before interviewing, the aim of the study was explained to the volunteers, and the confidentiality issues were discussed. The permission to record the interview was obtained concerning the proper protection of the audio documents. The participants ensured that the information would be applied just for the research without revealing their identity. The right to leave the interview at any time was among the other ethical considerations of the present study. The individuals then entered the process of a 1-h interview. During the interviews, there were two facilitators, one conducting the interview and the other recording the participants' feelings and reactions. Data collection continued to acquire relative saturation. Eventually, ten individuals were interviewed.

For managing, organizing and analyzing the data, Braun and Clarkes thematic analysis method (16, 17) was used. The recorded interviews were first transcribed in Word software for the content analysis. Then, the text was read several times, and the meaning units were extracted to understand the interviews' content in line with the research question. The codes were summarized and classified according to their similarity in the following. The information obtained was then discussed in meetings with the research team.

In order to evaluate the validity, credibility, and dependability of the research findings, two review methods, member check and peer reviewers check, were applied. After completing the data analysis, the findings were checked with the individuals who participated in the study. The data were analyzed again by another expert and compared to the analysis results of the researchers of the present study.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Mental Health Research center at the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS). All participants filed an informed consent form reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of IUMS. The researchers keep the names of the participants confidential and do not disclose information that may lead them to be recognized.

Results

Ten male participants aged 19 to 45 (mean age = 26) were interviewed. Their residence in Iran was between 20 days and 8 months. Six participants were refugees, and 4 were immigrants. Four were single, and the rest (6) were married.

Tsunami of suffering

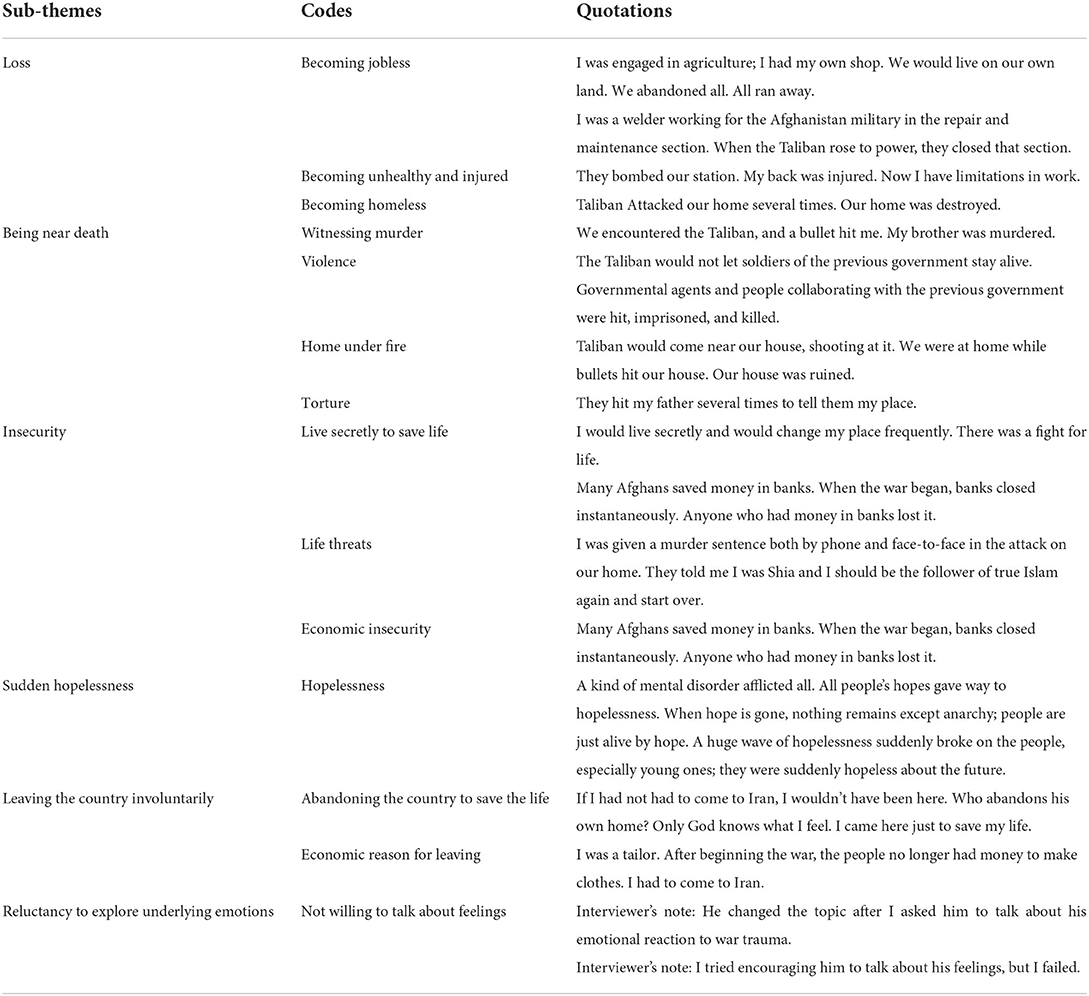

This theme represents widespread changes, disruption of normal flow of life, and impending danger of being murdered, which leads to widespread community fear. The changes took place rapidly and affected their life negatively in different ways; many aspects of their lives were influenced. The experiences are represented in six subthemes: loss, near death, insecurity, sudden hopelessness, leaving the country involuntarily, and reluctance to explore underlying emotions. The last subtheme is derived from interviewer notes and was seen in all participants; and reaffirmed by supplementary interviews with another interviewer. Table 1 shows the sub-themes, codes, and quotations of the Tsunami of suffering theme.

Lost in space/dangerous escape to Iran

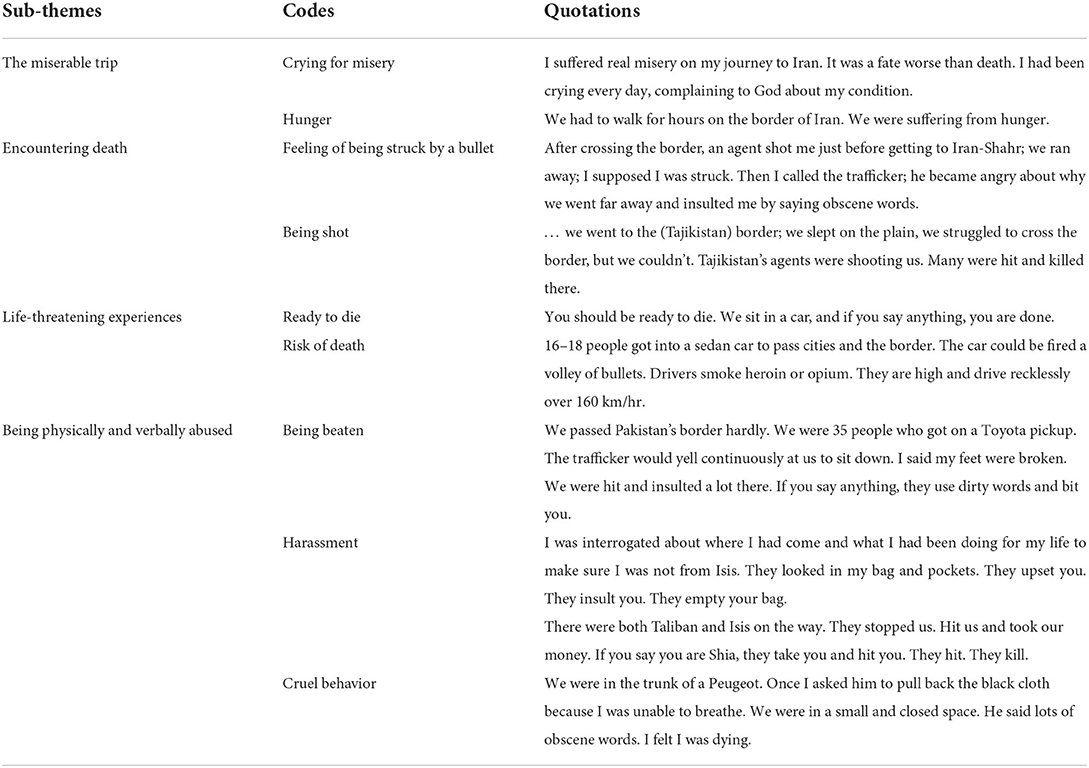

The participants attempted to leave Afghanistan after extensive losses and violent death threats. However, this was not easy. They had to leave the country secretly and illegally and with the help of human traffickers. They had to tolerate misery in Afghanistan and Iran and take considerable risks on this journey. The participants' experiences in this trip are categorized into four subthemes: the miserable trip, encountering death, life-threatening experiences, and being physically and verbally abused. Table 2 shows the sub-themes, codes, and quotations of the Traumatic Escape theme.

From being a citizen to being a refugee

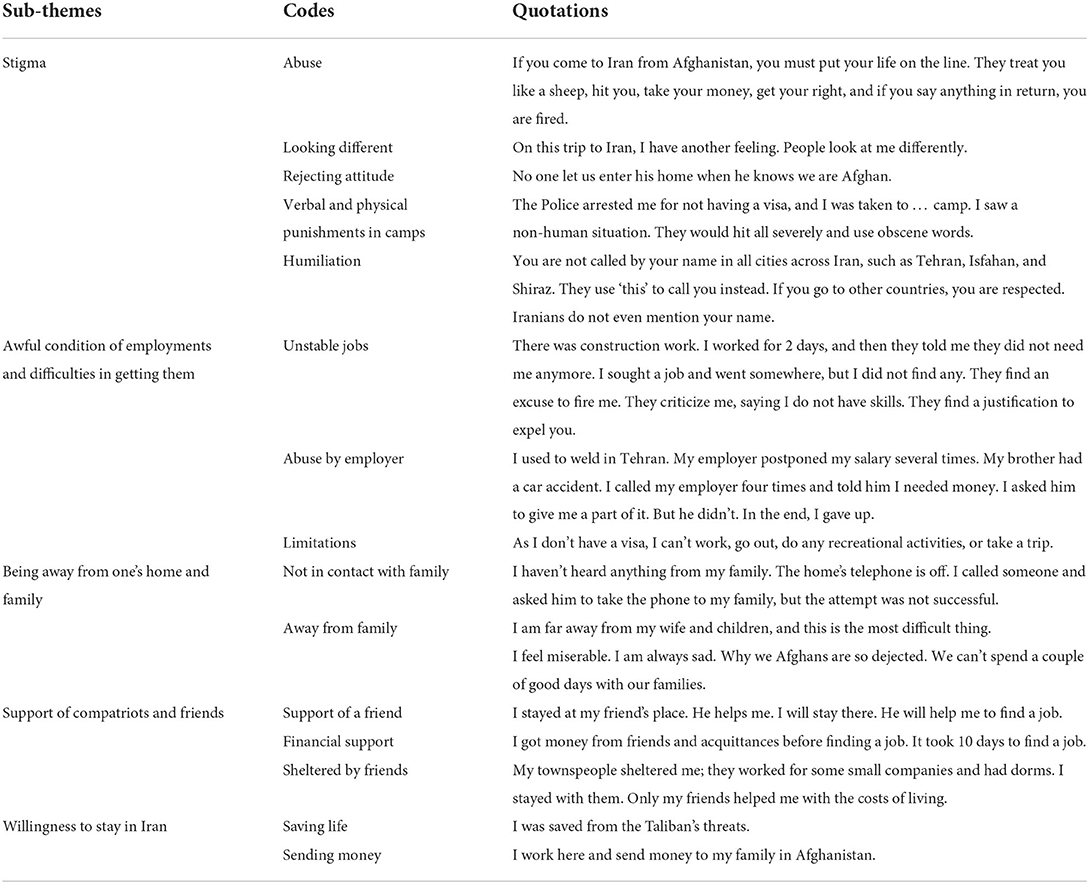

This theme is about the participants' experiences after getting to their destination in Iran. The related data are categorized into five sub-themes: stigma, awful condition of employment and difficulties in getting them, being away from one's home and family, support of compatriots and friends, and reasons for staying in Iran.

The stigma sub-theme describes how the participants are viewed and treated differently because of their nationality. The second sub-theme, related to stigma, represents the participants' struggles to find a job and their particular problems in the workplace. One significant misery of them is being away from their families. Some of them did not have any news from their family. Amongst these stresses, the help and support of a friend or compatriot play a significant role in spending the initial period on finding a job and adapting to the situation. The last sub-theme explains that they endure the condition and stay here despite their complex condition in Iran. Table 3 shows the sub-themes, codes, and quotations of the From Being a Citizen to Being a Refugee theme.

Challenges of the COVID-19

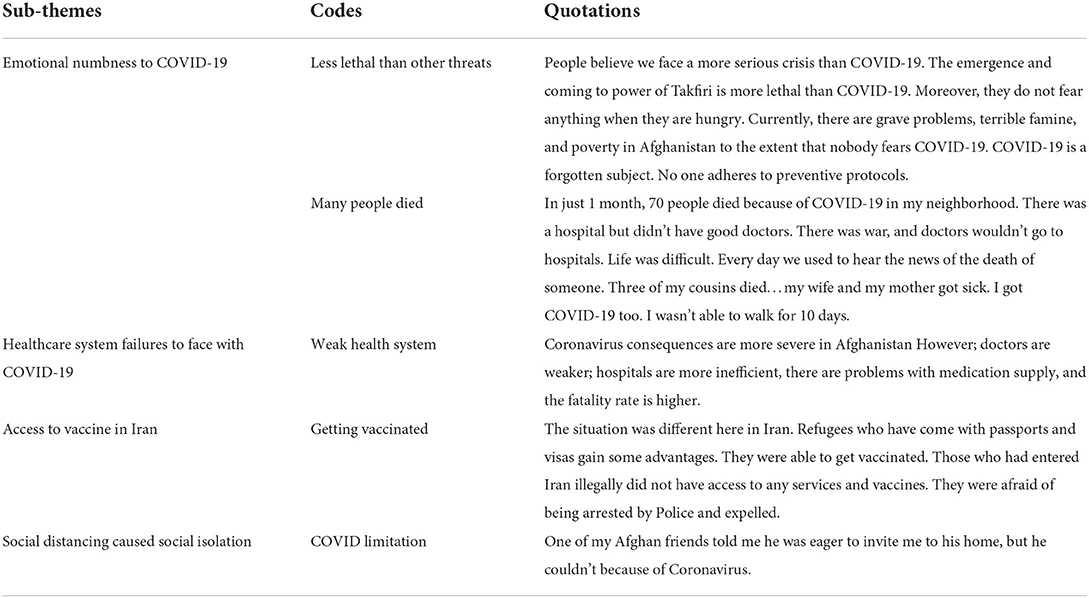

The experience of Taliban return, war trauma, running away, and living as a refugee or immigrant coincided with the COVID pandemic. The first sub-theme shows the participants' beliefs that COVID-19 was not a priority in their country and had to deal with more critical problems. They got used to hearing the death of people without doing something against it. The second sub-theme is about failures of the health system against COVID-19 both in Iran and Afghanistan. The participants' problems in getting vaccinated in Iran are represented as the third sub-theme. Due to the restricted social network of the participants in Iran, the restriction imposed by COVID-19 had a significant effect on them and led to more social isolation. Table 4 shows the sub-themes, codes, and quotations of the Challenges of the COVID-19 theme.

Discussion

This study explored the inner experiences of war induced sudden breakdown of the lives of Afghans, the traumatic escape, a change from being a citizen to a refugee, and their reciprocal interaction with the worldwide challenges of COVID-19 pandemic. War is an objective and massive trauma that severely impacts individuals' mental and physical health. While Afghan people fled to save their lives after the Taliban currently took over the country, they had challenging experiences during and after their migration. Iran has been a host country for Afghan immigrants and refugees for the last three decades. However, during the pandemic crisis, the experience of relocation was more complicated.

Interviewing ten Afghan immigrants, the Tsunami of suffering was the main theme of their lived experience in recent years. They lost their job, home, and physical wellbeing. The survivors who accepted to interview were near death; they witnessed murder, violence, torture, and their home under fire. They felt insecure and hopeless and forced to leave the country either as a refugee or by holding a Visa. We found that they were reluctant to express their emotions, a hallmark of being seriously traumatized.

We found another main theme; the feeling of being lost in space while they had to escape to Iran. They explained their miserable trip and encountering death in their journey. They experienced life-threatening events and were physically and verbally abused.

The third main theme was the feeling of transforming from a citizen in their homeland to a refugee in their host country. They felt discriminated against and stigmatized. They explained the awful condition of employment and difficulties in maintaining their job, resulting in hopelessness and depression. They also described the vital support of their compatriots and friends. Their main reasons for staying in Iran were saving their lives and sending money to their families in Afghanistan.

The final theme was challenges of the COVID-19, which, surprisingly, felt like nothing to them. They were primarily numb to COVID-19. However, they explained the healthcare system's failures to face COVID-19 and the difficulties accessing vaccines in Iran. According to the quarantines, they could not receive enough support from their families and friends in Iran and felt socially more isolated.

A single trauma can result in mental disorders, but multiple and chronic cumulated traumas disrupt a person's mental integrity and dissociative self-state (18). Our interviewees explained multiple and successive traumatic experiences of war, migration, and the pandemic. They were dissociated and emotionally numb when describing their experience, which is a hallmark of experiencing severe, unprocessed traumas.

The threats to one's survival provoke anxieties that reflect concerns over survival, self-preservation, and safety (18). The central clinical features of survivors are fears of losing control, being overwhelmed, and inability to cope. In addition, the feeling of entrapment and sense of disintegration of self, emptiness, humiliation, and fears of abandonment or need for support may complicate the condition (18). Our interviewees experienced a tsunami of suffering, including fears, entrapment, and disintegration of their selves. They felt abandoned and not only lost their family support in their homeland but could not also receive support in Iran due to the pandemic-related social distancing and isolation.

The findings of our study were consistent with another study that determined a high prevalence of discrimination, including health disparities for immigrants in the host countries (19). Our interviewees described their difficulties, including discrimination in access to vaccines in Iran amid the pandemic.

Based on another study (20), immigrants feel more sadness, depression, and loneliness several years after immigration than when they initially arrived. Challenges like lower income, acculturation and ethnic identity, and discrimination make them more vulnerable over time (18). Afghan refugees in Iran are a significant minority group vulnerable to physical and mental disorders. Enhancing their wellbeing in Iran during the following years requires precise and delicate planning. Providing proper mental and physical healthcare support and de-stigmatization programs are suggested.

One of our methodological limitations was related to the nature of the traumatic experience itself. Our interviewees were dissociated and emotionally numb when describing their experiences; we know this is a hallmark of experiencing severe, unprocessed traumas. However, these psychical defense mechanisms may be a barrier to a depth interview in the qualitative study. In addition, it was difficult for some interviewees to trust the interviewer. Because of their illegal residence in Iran, they refuse to give detailed information about themselves.

Since we had not had any other study in this area in Iran before, the finding of this study should be regarded as preliminary and suggestive. We need more study on more comprehensive ranges of people and include other resources such as writing and arts. Moreover, a data triangulation approach is needed in future studies.

According to the finding of this study, it is crucial to deliver primary care and mental health services to Afghan immigrants regardless of their immigration documents. Health systems can give services with their national ID and ensure that their data will not be used to recognize or expel them. Simultaneously, health professionals should be trained to be familiar with their specific problems.

Conclusion

We sought to develop a richer understanding of the experiences of Afghan residents in Iran during the Taliban's dominance in their country amid the pandemic. Multiple pre-and post-migratory traumatic experiences affect immigrants' physical, psychological, social, and economic wellbeing. The coronavirus outbreak also complicated their situation. They encounter disruption of the normal flow of life due to loss, being near death, and insecurity. Their miserable trip, life-threatening experiences on their way to Iran, their difficult life situation in Iran, and the challenges of the COVID-19 had worsened the situation. Providing social and health care support in Iran may reduce the impact of multiple traumas on their wellbeing.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Mental Health Research Center. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HM, MR, NS-M, and GM made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. SB had a substantial contribution to data gathering. ME analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors were contributors to writing the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Otoukesh S, Mojtahedzadeh M, Sherzai D, Behazin A, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Bazargan M, et al. retrospective study of demographic parameters and major health referrals among Afghan refugees in Iran. Int J Equity Health. (2012) 11:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-82

2. Lipson JG. Afghan refugees in California: mental health issues. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (1993) 14:411–23. doi: 10.3109/01612849309006903

3. The UN Refugee Agency. (2021). Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/ir/refugees-in-iran/ (accessed April 04, 2022).

4. Jesuthasan J, Sonmez E, Abels I, Kurmeyer C, Gutermann J, Kimbel R, et al. Near-death experiences, attacks by family members, and absence of health care in their home countries affect the quality of life of refugee women in Germany: a multi-region, cross-sectional, gender-sensitive study. BMC Med. (2018) 16:15. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-1003-5

5. Miller KE, Omidian P, Rasmussen A, Yaqubi A, Daudzai H. Daily stressors, war experiences, and mental health in Afghanistan. Transcult Psychiatry. (2008) 45:611–38. doi: 10.1177/1363461508100785

6. Zbidat A, Georgiadou E, Borho A, Erim Y, Morawa E. The perceptions of trauma, complaints, somatization, and coping strategies among Syrian refugees in Germany-a qualitative study of an at-risk population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:693. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030693

7. Sagbakken M, Bregard IM, Varvin S. The past, the present, and the future: a qualitative study exploring how refugees' experience of time influences their mental health and well-being. Front Sociol. (2020) 5:46. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.00046

8. Habtamu K, Desie Y, Asnake M, Lera EG, Mequanint T. Psychological distress among Ethiopian migrant returnees who were in quarantine in the context of COVID-19: institution-based cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:424. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03429-2

9. Rosenthal T. Immigration and acculturation: impact on health and well-being of immigrants. Curr Hypertens Rep. (2018) 20:70. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0872-0

10. Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus infections-more than just the common cold. JAMA. (2020) 323:707–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757

11. Tsang HF, Chan LWC, Cho WCS Yu ACS, Yim AKY, Chan AKC, et al. An update on COVID-19 pandemic: the epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention and treatment strategies. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2021) 19:877–88. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1863146

12. Jahangiri K, Sahebi A. Social consequences of covid-19 pandemic in iran. Acta Medica Iranica. (2020) 58:662–3. doi: 10.18502/acta.v58i12.5160

13. World Health Organization. COVID-19. (2022). Available online at: https://covid19.who.int/table (accessed April 04, 2022).

14. Aragona M, Barbato A, Cavani A, Costanzo G, Mirisola C. Negative impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health service access and follow-up adherence for immigrants and individuals in socio-economic difficulties. Public Health. (2020) 186:52–6. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.055

15. Alemi Q, Stempel C, Siddiq H, Kim E. Refugees and COVID-19: achieving a comprehensive public health response. Bull World Health Organ. (2020) 98:510–A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.271080

16. Hurvich M. The place of annihilation anxieties in psychoanalytic theory. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. (2003) 51:579–616. doi: 10.1177/00030651030510020801

18. Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitat Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

19. Chang CD. Social determinants of health and health disparities among immigrants and their children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2019) 49:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2018.11.009

Keywords: war, immigration, COVID-19, Afghan, Iran

Citation: Mohammadsadeghi H, Bazrafshan S, Seify-Moghadam N, Mazaheri Nejad Fard G, Rasoulian M and Eftekhar Ardebili M (2022) War, immigration and COVID-19: The experience of Afghan immigrants to Iran Amid the pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 13:908321. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.908321

Received: 30 March 2022; Accepted: 07 July 2022;

Published: 28 July 2022.

Edited by:

Renato de Filippis, Magna Græcia University, ItalyReviewed by:

M. Alvi Syahrin, Immigration Polytechnic, IndonesiaCarlos Miguel Rios-González, National University of Caaguazú, Paraguay

Copyright © 2022 Mohammadsadeghi, Bazrafshan, Seify-Moghadam, Mazaheri Nejad Fard, Rasoulian and Eftekhar Ardebili. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mehrdad Eftekhar Ardebili, bWVocmRhZC5lZnRla2hhckBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Homa Mohammadsadeghi

Homa Mohammadsadeghi Solmaz Bazrafshan

Solmaz Bazrafshan Negar Seify-Moghadam

Negar Seify-Moghadam Golnaz Mazaheri Nejad Fard2

Golnaz Mazaheri Nejad Fard2 Maryam Rasoulian

Maryam Rasoulian Mehrdad Eftekhar Ardebili

Mehrdad Eftekhar Ardebili