- Research Centre for Trauma & Dissociation, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Katowice, Poland

Few studies on Possession Trance Disorder (PTD) describe diagnostic and research procedures in detail. This case study presents the clinical picture of a Caucasian Roman-Catholic woman who had been subjected to exorcisms because of her problems with affect regulation, lack of control over unaccepted sexual impulses, and somatoform symptoms accompanied by alterations in consciousness. It uses interpretative phenomenological analysis to explore meaning attributed by her to “possession” as a folk category and a medical diagnosis; how this affected her help-seeking was also explored. This study shows that receiving a PTD diagnosis can reinforce patients' beliefs about supernatural causation of symptoms and discourage professional treatment. Dilemmas and uncertainties about the diagnostic criteria and validity of this disorder are discussed.

Introduction

Possession is a broad folk category used to explain a variety of symptoms or problems (1). It is frequently associated with possession-form presentations, marked by: talking in a different voice, sensation of paralysis, shaking, glossolalia or making animal sounds, or “night dances” (2). Members of different religious groups also explain possession as incomprehensible somatic symptoms, difficulties in spiritual practice or even problems in relationships (3–11). Furthermore, people in many groups perceive exposure to inappropriate music or films, using substances, masturbation, homosexuality or extra-marital sex as spiritual threats or indicators of being possessed per se (12, 13). Even delusions of possession in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders can be ascribed by some priests and community members to demonic possession (14). Although people labeled as “possessed” represent a heterogeneous group in terms of clinical presentations, many anthropologists view possession as an idiom of distress and a way of communicating or expressing protest by those who are marginalized or subordinate (15, 16).

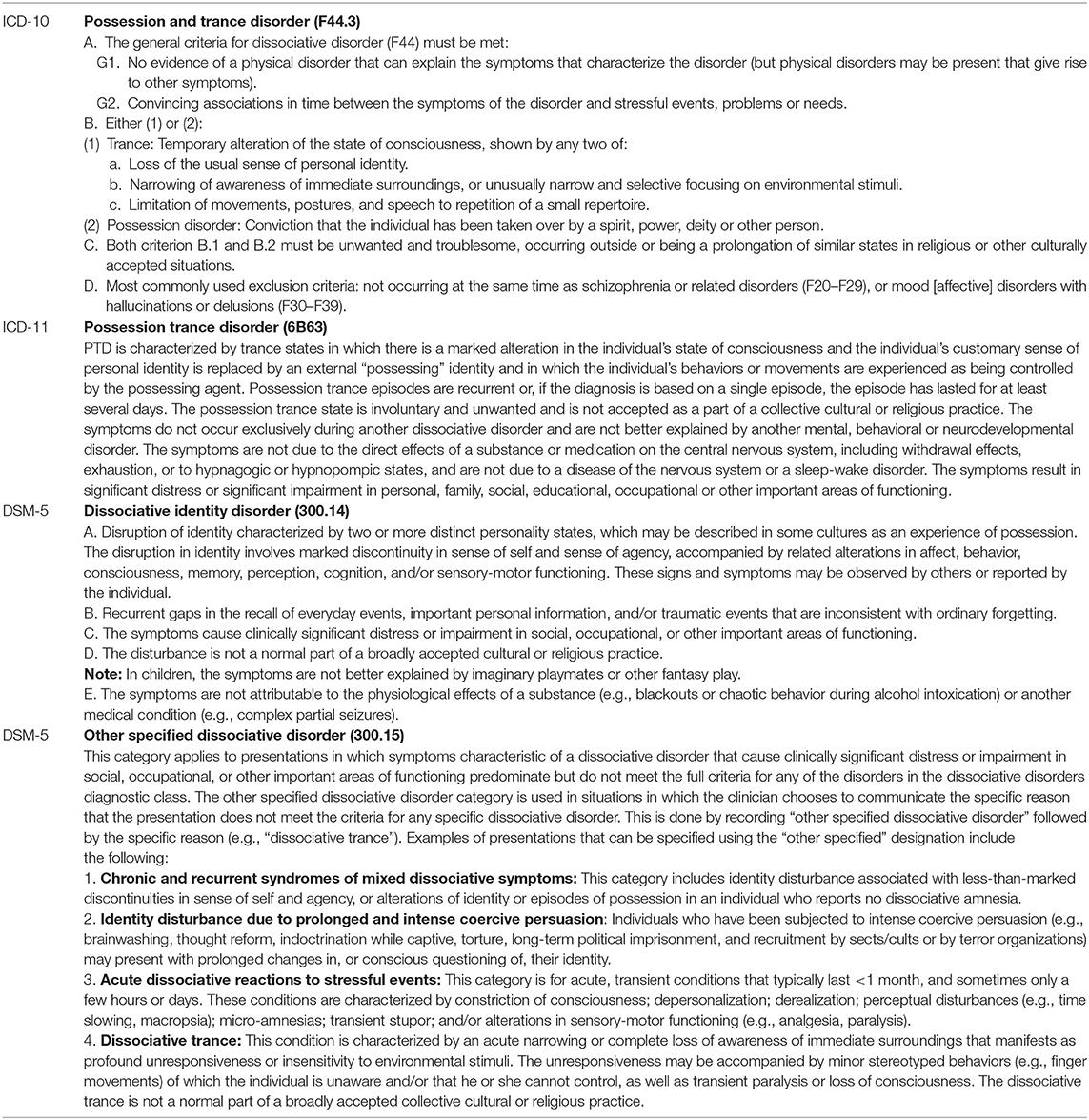

The concept of possession has also been used in psychiatric language (see: Table 1). The 10th and 11th editions of the WHO classifications list Possession and Trance Disorder (PTD) in the dissociative disorders chapter. ICD-11 describes it as: “a marked alteration in the individual's state of consciousness and the individual's customary sense of personal identity is replaced by an external ‘possessing' identity and in which the individual's behaviors or movements are experienced as being controlled by the possessing agent” (17). Symptoms should be involuntary and unwanted, and should not be a part of a collective cultural or religious practice (e.g., Cavadi, deliverance ministries), because suggestible individuals may be prone to exhibit behaviors expected in such situations, especially if they have been exposed to trance states or received teachings about possession. For this reason, possession-form presentations triggered by and occurring only during exorcisms should not qualify for this diagnosis (13). Symptoms should also lead to significant distress or impairment in personal, family, social, educational or occupational functioning (17). However, adopting the role of someone “possessed” can be a source of different gains: primary (abreaction or an opportunity to express conflicting impulses in a culturally acceptable manner) and secondary (attracting the attention of others and evoking respect or awe). According to the ICD, unless these trance episodes are recurrent, a single episode should last at least several days to qualify for this diagnosis. Full or partial amnesia is expected for the trance episode. ICD-11 outlines very superficial boundaries between PTD and Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) or Partial DID: alternate personality states in PTD are attributed to an external (not internal) possessive agent. This implies there is little difference in the overall clinical presentation of PTD and complex dissociative disorders, except for how patients make meaning of their symptoms.

In the American classification, “possession” was diagnosed as the Atypical Dissociative Disorder diagnosed in DSM-III or DDNOS in DSM-III-R. In DSM-IV (1994), possession and trance were diagnosed as sub-categories of the Dissociative Trance Disorder (DTD), and in DSM-IV-TR they were merged into one, and recognized as a cultural variant of the Dissociative Disorder Not Otherwise Specified [DDNOS, (18)]. In DSM-5 (19), possession-form presentations are linked with criterion A of DID: “Disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states, which may be described in some cultures as an experience of possession” (p. 292). In the absence of other salient DID features (e.g., amnesia), possession episodes can still be coded under the Other Specified Dissociative Disorder (OSDD) category.

However, only some people with possession-form presentations report clusters of symptoms characteristic of complex dissociative disorders such as DID (10, 20–22). In contrast to that, possession-form presentations in PTD comprise some dissociative symptoms not matching criteria for complex dissociative disorders. Other patients with possession-form presentations are better described in terms of personality disorders, marked by problems with attachment, affect regulation, and internal conflicts associated with aggressive or sexual impulses which they can express in a culturally-legitimate manner (4, 11, 13, 23, 24). These people can be encouraged by community members to attribute unacceptable or shameful impulses to demonic influence. In this way, they can externalize psychological conflicts, reduce feelings of guilt or attract others' attention. According to Pietkiewicz et al. (13) there are qualitative differences between these disowned ego-states and autonomous dissociative parts in complex dissociative disorders, and treating these people as if they had such parts could be iatrogenic. Unfortunately, in patients referred by exorcists for diagnostic assessment of their possession-form presentations this diagnosis is rarely taken into account.

It is intriguing how clinicians' personal beliefs about the phenomenal world (e.g., whether or not invisible entities exist which can influence human behavior) affect clinical judgement and meaning attributed to symptoms. Bayer and Shunaigat (25) postulate, for instance, that ‘real' possession should be differentiated from the nosological spirit possession category. Some authors also mention consulting priests or healers (12, 26), but their role in the diagnostic decision-making was not clear. On the one hand, this might express clinicians' sensitivity to patients' religious beliefs and their expectations to involve spiritual leaders in the treatment plan. On the other hand, it could also reveal clinicians' own doubts about the nature of the symptoms. Inability to explain them in terms of psychological mechanisms responsible for a given problem can lead some professionals to consider non-medical explanations. For example, Khan and Sahni (27) explicitly shared their belief that “exorcists, at times, are able to tell whether a person has a mental illness and requires hospitalization and drug treatment or is truly possessed” (p. 254). In another case study by Hale and Pinninti (26), prison and hospital chaplains concurred on “genuine” possession of a patient leading authors to the following conclusion: “If we are to accept that there is a place for belief in real possession in current thinking, then what we have described above might be construed as a case of exorcism-resistant ghost possession, successfully treated with a depot neuroleptic” (p. 388).

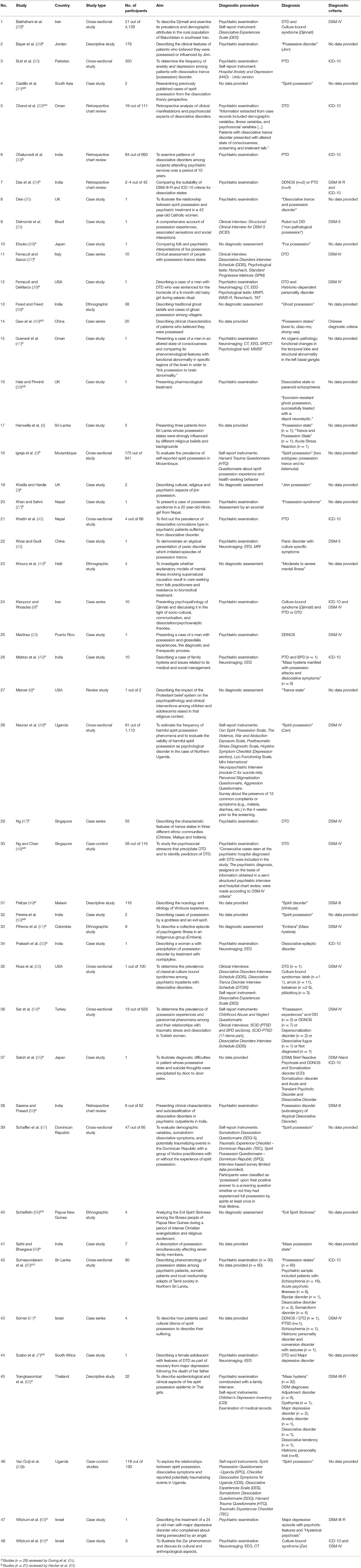

Assuming that guidelines for diagnosing possession episodes and information about their prevalence or risk factors quoted in psychiatric manuals are based on research, we decided to review the procedures which were applied to make diagnoses in 48 studies exploring symptoms of possession and trance (see: Table 2). We included publications previously examined in systematic reviews by During et al. (65) and Hecker et al. (66). These two were the only reviews of PTD/DTD available. We also identified nine additional studies of PTD not included in previous reviews. The majority of research on possession-form presentations consists of case studies describing phenomenological aspects, but offering meager descriptions of participants' clinical presentations which could facilitate differential diagnoses. In their reviews, both During et al. (65) and Hecker et al. (66) also included anthropological publications or ethnographic accounts, and studies in which participants obtained other diagnoses, but they were treated as examples of PTD. In 25 studies, diagnoses were based on general psychiatric examination during which patients reported changes in behavior which they attributed to demonic possession. However, authors provided no information about the scope of these clinical interviews and how differential diagnoses were made. Twenty studies suggested the PTD/DTD diagnosis but there was no diagnostic assessment performed by a mental health professional or they contained no information about assessment whatsoever. In four of these studies, assessment was limited to self-report instruments which cannot be regarded as a satisfactory diagnostic procedure per se. In four studies diagnoses were determined retrospectively based on analyzing medical records (32–34, 56). Only in four studies, in-depth clinical interviews were used in the assessment, e.g. the Dissociative Disorder Interview Schedule, DDIS (37, 53) and the Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM–IV (SCID) or parts of it (20, 54).

Considering the above, rigorous clinical studies exploring possession-form presentations are paramount. They should go beyond phenomenological descriptions and analyze participants' overall functioning in different areas, symptom dynamics, psychological conflicts and mechanisms, attribution of meaning and potential gains. While diagnostic manuals emphasize patients' meaning-making, few studies explored how patients made sense of being diagnosed with Possession Trance Disorder, and how this affected their help-seeking behavior. This case study describes the clinical presentation of a Catholic woman referred for a diagnostic assessment by priests who grew helpless about her aggressive behavior and acts of vandalism. What meaning she ascribed to her PTD diagnosis and how it affected her help-seeking pathways during a 3-year period until a follow-up interview was also analyzed

Methods

This study was carried out in Poland between 2016 and 2021. Qualitative data included clinical interviews and psychiatric mental health assessment. Their transcripts were subjected to Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), which is grounded in phenomenology, hermeneutics, and idiography (67). IPA explores participants' experiences and interpretations, followed by researchers trying to make meaning and comment on these interpretations. Samples in IPA studies are small, homogenous, and purposefully selected. Qualitative material is analyzed in detail case-by-case (67, 68). IPA was chosen for this case study to explore the help-seeking pathways and meaning attributed to the diagnosis of a Possession Trance Disorder.

Procedure

This case study is part of a larger project examining phenomena and symptoms reported by people using exorcisms. This project was held at the Research Center for Trauma and Dissociation, financed by the National Science Center Poland, and approved by the Ethical Review Board at SWPS University. Potential candidates enrolled themselves via a dedicated website, or were registered by healthcare providers and pastoral counselors. They filled in demographic information and completed online tests, including: Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire [SDQ-20, (69)], Dissociative Experiences Scale - Revised [DESR, (70)]. (Elevated scores in these tests, SDQ-20 ≥30 and DESR ≥72, are suggestive of dissociative disorders). They were then subjected to semi-structured interviews exploring their biography, family situation, religious socialization and spiritual involvement, and motives for enrolling in the study, followed by a diagnostic consultation using Trauma and Dissociative Symptoms Interview [TADS-I, (71)]. The TADS-I is a semi-structured interview intended to identify DSM-5 and ICD-11 dissociative disorders. It includes a significant section on somatoform dissociative symptoms and a section about other trauma-related symptoms. The TADS-I also explores symptoms indicating a division of the personality and alterations in consciousness. Interview recordings were assessed by three healthcare professionals experienced in the dissociation field, who discussed each case and consensually came up with a diagnosis based on ICD-11. This interview was followed by an additional mental state assessment performed by the third author, who is a psychiatrist. He collected medical data, double-checked the most important symptoms, confirmed and communicated the diagnosis and discussed available coping strategies. All interviews and the medical consultations were divided into 60 min sessions.

Among 23 people who enrolled in the project, 12 had features of a personality disorder, five had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, two met ICD-11 criteria for partial DID, two had Complex PTSD, one had a Dissociative neurological symptom disorder, and one had Possession Trance Disorder. The person with PTD was selected for this analysis. An additional follow-up interview was performed with her 3 years later to explore the meaning she had attributed to her diagnosis and how it influenced her help-seeking behavior. The total length of all interviews conducted with her was 8 h 46 min.

The Participant

This is a case study of a 42-year-old woman (who will be called Emma). She had secondary education, was divorced, and raised by herself her 10-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son with autism spectrum disorder. She remained unemployed and used care allowance. Emma came from a very religious family and was raised by mother and grandparents. No one used psychiatric treatment in her mother's family and there was no information about that from the father's side. Her father was born in a Nazi concentration camp and after the war he relied on financial compensation. He was much older than Emma's mother, aggressive, and abused alcohol. He left the family before Emma's first birthday, and reappeared every 6 or 12 months thereafter. According to Emma, her mother was controlling and turned her against her father. Emma also perceived herself as a solution for her mother's pain after miscarrying a child shortly before Emma had been conceived.

Emma had a good relationship with her maternal grandfather, who was supportive and a model of morality and piety. He led her to develop her interest in religion when she was in primary school, but he died when she was 15. Around that time her problems with aggressive or auto-aggressive behavior started, as well as attention seeking by unlawful behavior and breaking school regulations. She became rebellious, and frequently quarreled with her mother who tried to control her social life and sexuality, before running away from home for a year to live in squats, abusing alcohol and drugs, and engaging in risky sexual behavior for money. She was sexually abused under the influence of substance a few times. In adulthood, she lived abroad for almost 10 years, earning money by providing sexual services. During that time she also experienced rape and threats. As she never had close friends, she only used support from priests who, based on her life history, believed she was possessed. She was first exorcized a few times in charismatic groups at age 16. In adulthood, she regularly used deliverance ministries and individual exorcisms according to Roman Catholic ritual for a few years, but her problems and symptoms persisted.

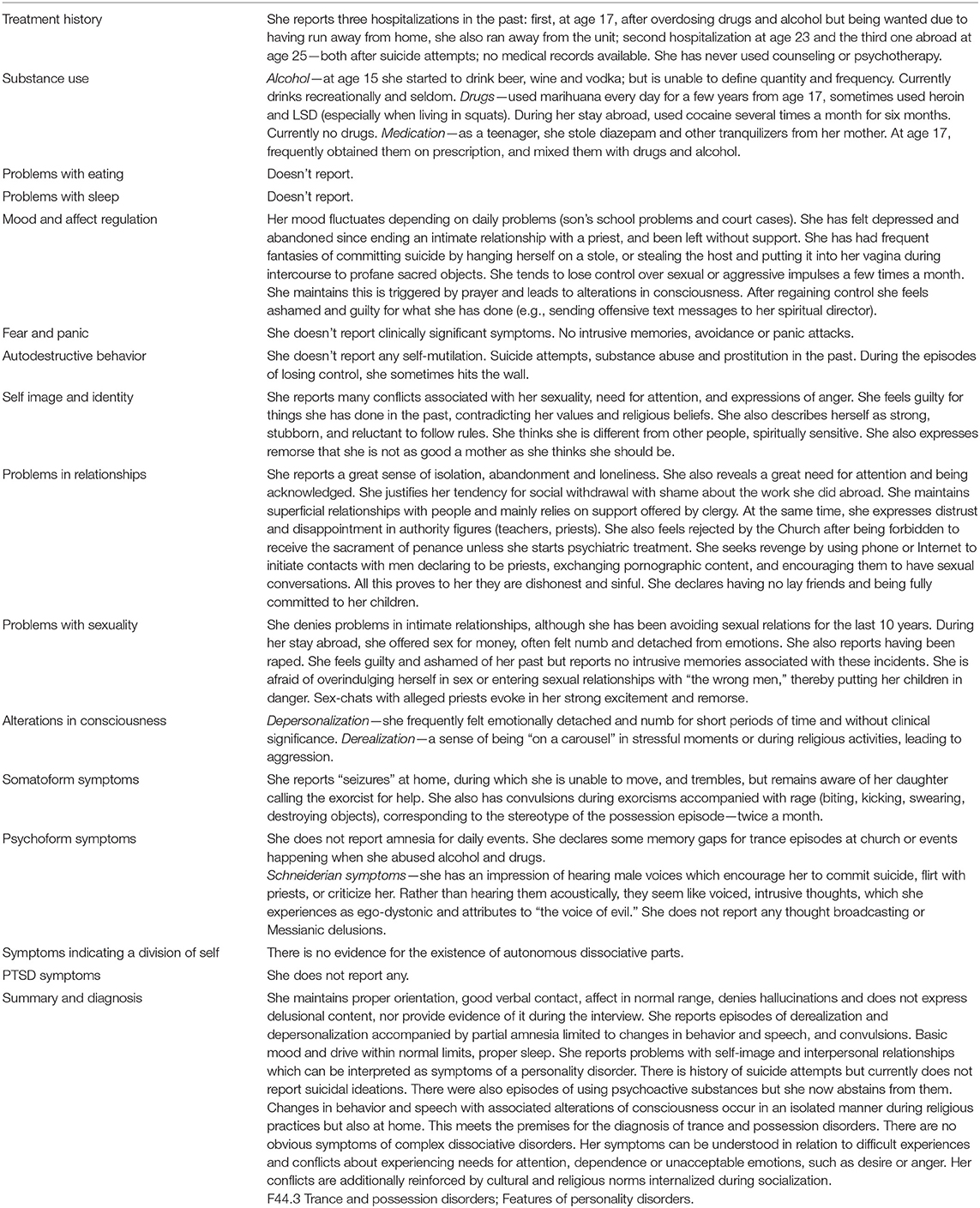

She had elevated levels of somatoform and psychoform dissociation (respectively, measured with SDQ-20 and DESR-PL). More information about her symptoms reported during the clinical interview and mental state examination is provided in Table 3.

Data Analysis

Recordings of all the interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed together with researchers' notes using qualitative data-analysis software (MaxQDA 2020 ver. 20.4.0). Consecutive IPA procedures were employed in the study (68). Researchers watched each interview and read the transcripts carefully. They individually made notes about body language, facial expressions, the content and language use, reported symptoms, and wrote down their interpretative comments using the annotation feature in MaxQDA 2020. Next, they categorized their notes into emergent themes by allocating descriptive labels. They then compared and discussed their diagnostic insights, coding and interpretations. They analyzed connections between themes and grouped them according to conceptual similarities into main themes.

Credibility Checks

During each interview, the participant was encouraged to illustrate reported symptoms or experiences with specific examples. Interviewers asked clarification questions to negotiate the meaning the participant wanted to convey. At the end of the interview, she was also asked questions to check that her responses were thorough. The researchers discussed her case thoroughly, including the diagnosis and interpretative notes to compare their understanding of the content and its meaning (the second hermeneutics).

Results

Emma shared in detail her life history, symptoms and coping strategies. During the follow-up interview (3 years after her assessment), she also described what it meant for her to be diagnosed with possession-trance disorder and how the diagnosis affected her help-seeking. Seven salient themes were identified during the analysis: (1) Excitement and guilt for crossing the taboo, (2) Seeking revenge on priests, (3) Possession-form presentations attracting public attention, (4) The idiom of possession, (5) Exacerbation of destructive behavior during exorcisms makes priests helpless, (6) Making sense of the psychiatric diagnosis, (7) Receiving pastoral counseling as an alternative to professional treatment.

Each theme is discussed and illustrated with verbatim excerpts from the interviews, in accordance with IPA principles.

Theme 1: Excitement and Guilt for Crossing the Taboo

Emma remembered being introduced to sex when she was six. Secret sex games with her 10-years-older cousin triggered excitement and pleasure, and at first she didn't think of them as harmful. It was only while preparing for her first communion that she learned during confession this was forbidden, shameful and sinful.

It started when I was six. It influenced me because it woke me up too soon and made me sexually licentious later on. I have never talked about it… it was during my confession that I admitted “playing immodestly.” The priest wasn't satisfied and wanted to know the details, he asked who it was with, but I couldn't tell him. I've always taken the blame.

In her secondary school, she repeatedly broke the rules and urged boys to masturbate in class. This excited her and could also make her feel she had control over their sexuality.

I ignored teachers and showed them I did not care. I didn't listen to them at all. I was also so promiscuous. I always sat on the last bench with the boys and forced them to masturbate. I was just very promiscuous.

In her adult life, sexuality became an important arena for inner struggles and conflicts, evoking strong guilt and self-loathing. Emma described sexual desire as “hell,” “the source of corruption” and “mental weakness.” There were periods when she suppressed her needs and abstained from sex and episodes of promiscuous behavior, prostitution, and abusing sexual partners. It seems that eroticism, which she used to regulate her emotions, may have taken the form of a behavioral addiction.

All this sexuality was hell and I would like to spare my children that. Erotica may seem like some kind of beautiful sensory stimulation, but in fact it is losing control over yourself… I was trapped in the claws of erotica, I was so spoiled in that regard. I often met guys who told me that I was hurting them. I just used them only for sex and treated them as objects. I think it was my way of avoiding getting hurt. I would rather take advantage of someone and abandon him, before he could do that to me.

She did seem to have some insight into her problems with attachment and might have used sex to gain control and hide her vulnerability. She thinks this allowed her to avoid emotional involvement with men.

Theme 2: Seeking Revenge on Priests

In Emma's mind, the Church forbade expressing sexual desire, and commanded abstinence by inducing guilt, shame, and sin. Some priests, like her older cousin when she was a child, both aroused her and were experienced as forbidden targets. She recalled an early exorcism:

These men were holding me face down on the floor. The priest sat on the back of my legs. He kind of lay down on me, holding my hands. He started stroking my hair saying “Accept this love of Christ” and… my body reacted against all reason. I also felt discomfort, because… something happened to me. For the first time I realized I had never thought about a priest before in that way. Looking at a priest, even a handsome one, I had never seen a man, but someone asexual. However, after this exorcism, I had erotic thoughts about him, for 2 weeks. It may have been because I had not been so close to a man for a long time, but common sense won and these emotions subsided. I broke off contact with this exorcist.

When she addressed these moral conflicts with her spiritual father, he first used confession and prayers to help her control sexual impulses. However, she said the relationship evolved into a love affair which made her feel guilty for crossing the taboo. She justified the priest's actions saying it gave her pleasure, which sounds like another repetition of her childhood history.

We became close and finally crossed the physical boundary between a man and a woman. I was not harmed in a physical sense, because it gave me pleasure. It had such an impact on me. Suddenly the whole world, even this whole image of the church, was blown up. I realized I had not overcome my weakness.

In order to deal with conflicting feelings she was seeking men who introduced themselves as priests, engaging them in sex chats and exchanging pornography, subsequently seeing them as equally sinful.

My confessor said we must stop seeing each other, that he was afraid of being alone with me. So I felt really alone. I got really into this virtual reality and started looking for priests who were addicted to erotica. I set up a profile called “Lady for a Priest” and they started contacting me. It was some kind of revenge on my part. Erotica with a normal guy ceased to be attractive—all I wanted was a clergyman. Saturday nights were so exciting, I told them all sorts of things and they masturbated and we exchanged photos. I thought of them celebrating Holy Mass the next day in a state of sin—I felt like a vampire feeding on their weakness, but it also hurt me a lot.

In her mind, Emma seemed to attack and destroy any ideas about the virtues of a person representing authority, morality, or ethics. This could have been a payback for being shamed for her sexuality and for being abandoned. It may also have let her experience moral triumph. However, she also realized that it brought about feelings of loss and pain.

Theme 3: Possession-Form Presentations Attract Public Attention

Emma learnt from her participation in religious youth camps that unusual behavior which group members ascribed to possession evoked awe and interest and could also lead to receiving special attention for which some adolescents competed.

I got involved in the Oasis movement when I was 15, and was encouraged to participate in a so-called Community Day, a kind of preliminary meeting and excursion. There were three other girls who were acting weird. One started having convulsions while singing. The priests surrounded her… they were standing tightly in a circle, so that no one could see what they were doing. I was really curious and wanted to see what was happening. Since I couldn't break through, I crouched to the side and said: “Satan, if it's your doing, leave her and enter me. I remain at your disposal.” At this point, I lost my temper.

This was the first time Emma's disruptive (violent) behavior was accompanied by derealization and convulsions. She later compared that state to feeling dizzy, as if “riding on a merry-go-round.” Emma remembered being given tranquilizers, which had a delayed effect. She emphasized this was unusual, which for herself and witnesses could have justified the supernatural causation of her state. She saw that youth camp experience as a turning point in her life, leading to further problems, spiritual conflicts, and concentration on religious coping strategies.

It was like being on a merry-go-round, a carousel. My clothes were torn—I fell on stones. The priests went on praying over that girl and after a while she calmed down. I calmed down too and we continued walking, but after a few meters I lost my temper again. It was awful. They called an ambulance and gave me sedatives but it had no effect. A priest said it was a dose for a horse, and it didn't work for me! It was only when the doctor took me to the ambulance away from the priests that I fell asleep so deeply that it was difficult to wake me later. My life has never been normal since.

Since then, in religious contexts Emma regularly experienced bouts of anger, convulsions, and derealization, which subsided when no priest was present. Religious people interpret that as aversion to the sacred—clergy see that as one criteria of genuine possession. Her attacks attracted the attention of others and, over time, she engaged in more provocative and socially unacceptable actions. For example, during youth camps she killed and sacrificed a cat. Another time, she had a possession-form presentation after a demonology lecture held at her Catholic high school.

I couldn't resist the temptation to do it, consciously and voluntarily, in front of them… I did a kind of ritual, I grabbed a cat and tore it apart with my hands. Then I offered it to Satan… total madness. Today I am terribly ashamed of it and I can't forgive myself. These girls were horrified because I tore apart a living creature, and most of them came from traumatized backgrounds… Once a priest came to our school and gave a talk about demonology. Me and other girls were preparing the setting and some songs for the holy mass. At one point, as I was going upstairs, I lost it… I started screaming, throwing myself around and hitting myself hard… A girl in my class attempted suicide by taking pills, and then another one. The nuns said it was my influence.

She emphasized that she knew what she was doing and apparently had no amnesia. Despite attributing aggressive impulses to demonic influence, she nevertheless feels guilty and ashamed of her actions. She also realized that she could negatively affect other people, which could also give her a sense of significance and power.

More recently, Emma experienced a strong temptation to steal the host with the aim of profaning it, or fantasized about committing suicide by hanging herself on a priest's stole. These actions shocked and were criticized by the clergy, but were also justified as the manifestations of evil, releasing her from responsibility.

For me, the black mass was the most perfect form of profanation, when the Blessed Sacrament is stolen and placed inside a vagina, preferably just before intercourse. And when the sexual act is done with a priest, it would be the so-called double profanation. I brought home the host and was going to profane it. Not only that… I was planning to commit suicide in a typical satanic ritual of death. I wanted to hang myself on a stole which I had stolen from the church.

Her ideas, which sound as if they were inspired by the Story of the Eye by Georges Bataille (72) were popular among people she met in squats, and became banned by the Church. There is no information whether Emma was familiar with such texts, but using the expression “so-called double profanation” suggests she shared common knowledge about the libertine movement.

Theme 4: The Idiom of Possession

Emma has extensively studied literature about demonology and watched local exorcists preaching on YouTube about “spiritual threats” and “spiritual warfare”. This has made her believe that premature or unwanted sexual activity, interest in occultism, exposure to foreign symbols, philosophies and treatments (e.g., magnetic healing) can make one prone to demonic possession.

When I was a child, the first bad thing that happened to me was the attack on my innocence, sexual I mean. That evil was silent, unnoticeable. Later, my grandmother took me to a magnetic healer, which only made things worse. You know, there is bad energy which can be transferred, because God does not bestow such healing powers. If he heals, it only happens through sacraments and prayer. Later, as a child, I had trouble praying. Every time I knelt down to pray, I felt that my prayer was wrong. Something prevented me from finishing it, so I had to get up and start over. These are things that led to this evil. And then it just got worse and worse when I got involved in drugs.

She also believed in so-called “manifestations” associated with the “aversion to sacrum.” These possession-form presentations are regarded as indicators of possession in a theological sense, and are often discussed by religious community members. Emma observed that since her first “possession” experience at the Oasis gathering (see: Theme 3), she grows agitated, angry, and gets convulsions during prayers. On the other hand, all her symptoms subside when she is not involved in religious matters. This only reinforced her belief that she is truly possessed.

I was recently playing with my kids at home and suddenly I started shaking. This merry-go-round appears and I bounce off the wall like a ball. I later found out that when this happened the priest was praying for me (my daughter knows him and called him for help). If he prays, it only prolongs everything. If he does not pray, my children call me back, they shout “mommy, mommy, mommy,” then I follow their voices and quickly return to my senses. The worst thing was when my daughter turned on the speakerphone and I could hear that priest praying. I had asked him never to do that when I was at home with the children, so that they are not threatened. It is not about me, but about the children. I don't want them to witness that. Unfortunately the priest… I guess, my daughter felt safe because he was praying. Maybe she felt she wasn't alone, but it only prolonged everything.

This reveals interesting interactions between Emma, her children and the exorcist. She seemed to experience conflicts about receiving attention and help. Her daughter sought refuge in the fatherly figure but, according to Emma, this only escalated her symptoms. She partially identified with the feelings of helplessness and abandonment of the 10-year-old girl, but also saw herself as a potential source of threat for her children.

During the interview, she reported strong temptations to do unacceptable things, which she ascribed to “inner voices” but denied having auditory hallucinations per se. Her “voices” were thought-like experiences and represented good and evil. Sometimes, she engaged in inner dialogues with them.

I have three voices inside and sometimes I talk to them. There is the good side which usually speaks softly, calms me down, and develops some sense of peace. The second voice usually exerts pressure. And there is my voice, that of my psyche, which questions the previous one and tries to make sense of it all.

Rather than perceiving them as an expression of her own mental activity, she attributed these thought-like voices to the supernatural, saying only individuals who believe in God could understand the spiritual dimension of such phenomena. She emphasized that they need to resolve conflicts between their instincts and moral values. The struggle between good and evil is not merely symbolic in her narrative, but attributed to concrete entities.

In order to understand these voices, one must acknowledge the existence of God because, if we reject the existence of God, the existence of these voices becomes irrational. Every Christian has this dimension of the struggle in his conscience. There is a good side, and there is a bad side.

Emma had endorsed and identified with the concept of possession and navigated between its clinical and theological meanings. Despite multiple and ineffective exorcisms, she seemed reluctant to accept priests' suggestions that she might have a psychological disorder. Even a clinical diagnosis, according to her, did not rule out spiritual causation of problems.

Even if someone is mentally ill, it does not mean that no devil's work is involved here, because the devil can work through disease. Satan wants to drive as many people as possible away from God. He will take advantage of every disease, every weakness or flaw which he can use to do evil.

She maintained that genuine spiritual possessions are uncommon but do occur and prove to the faithful the existence of the supernatural.

I think possession, from this theological point of view, is something which rarely or practically never happens. And when it does happen, it's like a sign from God to confirm that this spiritual world exists.

Theme 5: Exacerbation of Destructive Behavior During Exorcisms Makes Priests Helpless

First attempts to expel evil spirits from Emma began when she was 15. She took part in deliverance ministries organized in a Christian group where the pastor and his male assistants took her aside and tried to tame her. Her agitation and resistance was interpreted as a sign of possession. Emma managed to escape one such event and, when news about this spread, the local parson and her mother forbade her from joining that group again.

They picked me up a few times and took me to the church. In this Christian community, a group of men—the pastor and his assistants—took me to a separate room and simply tried to force the evil spirit out of me. When I resisted, they used physical force… they tied my hands, they sat on my legs, someone sat on my arm. They hit me and used gestures to chase away the evil. It was like in American films. I felt they were crossing my boundaries but when I tried to protest they saw it as the manifestation of evil. It was painful and I was bruised and torn. I broke free once and ran away, leaving my things behind. I went to the parish and asked for help. The parish priest and my mother were told about everything and they insisted I never go there again.

Because her behavior was inappropriate and scandalous in high school, nuns who ran the school sent her to an exorcist. During this and subsequent rituals she grew more and more violent, offended priests, damaged chapels, and became even more furious when they tried to restrain her.

After leaving hospital [after a suicide attempt], I sought help in the parish. One priest arranged a meeting for me at the church with three other priests who wanted to pray with me, but I just… just demolished the church. I smashed figures, windows, and broke benches. They were unable to do anything and even called the police. The priest said he couldn't help and I must be taken to an exorcist.

Being labeled as “possessed” legitimized Emma's aggressive behavior toward authority and allowed her to feel she had special spiritual significance. It was also the source of secondary gains: she received special attention and emotional support from clergy. Perhaps this is why she was reluctant to give up on the priests, even when there was no improvement and they felt helpless against her behavior. Over time, she consulted different exorcists who subjected her to exorcism, until they questioned her possession and insisted on a psychiatric consultation.

I visited the Pauline order for the deliverance ministry and was flailing around all day. After praying over me for a long time they gave up and said it might be a mental illness because the prayers weren't working. They hoped I would change and calm down under their influence but I was flailing as long as they were praying. Finally, they came to the conclusion that I must be mentally ill and the Church could not help.

Theme 6: Making Sense of the Psychiatric Diagnosis

Emma obediently went for a diagnostic appointment as if on her own initiative. She revealed some disappointment with exorcists who had tried to help her. She saw them as helpless and confused, but also ascribed a certain level of arrogance to them.

I would like someone to look at my experiences from a different, specialized perspective, unlike the one provided by priests. There are many exorcists in Poland but these priests are very confused, although they think they are wise and know best.

She seemed certain in her beliefs about demonic agency and was reluctant to consider alternative explanations for her aggressive and sexual impulses. Despite receiving psychoeducation about emotional regulations and the meaning of PTD, she felt that by using the term “possession” clinicians only supported her theories.

In the follow-up interview 3 years later, Emma could not hide her disappointment that the priests had lost interest in her case. It seems that receiving a medical diagnosis was an excuse for them to stop further exorcisms and deny her sacraments unless she started psychiatric treatment. Paradoxically, Emma said this proved their fear and helplessness about her being genuinely possessed, which she thinks was only confirmed by mental health specialists.

This diagnosis is not so clear… In people from outside, it evokes… because if something is not clearly specified, indicated in writing, then you may still hesitate and have different theories. When they have confirmation that they are dealing with something… For example, when I gave this [report] to the confessor [takes a loud breath], when he read “trance and possession,” for him there was no medical dimension, he wasn't thinking in medical or psychological terms, but theological. In theological terms, there is some force, a force that is beyond your powers… I came to the conclusion that before I had this [PTD] diagnosis, they kept trying to help me and willingly controlled my life. But when they realized I was possessed, they just stopped because it was too overwhelming for them… They completely rejected me, avoided any kind of services, confession.

Subsequently, she also broke her contacts with charismatic groups and moved to another town. She still celebrated holy mass every Sunday but withdrew from all groups and focused on helping her children adapt to a new environment. Her convulsions and derealization (feeling of merry-go-round) disappeared.

Theme 7: Receiving Pastoral Counseling as an Alternative to Professional Treatment

Although being denied further exorcisms caused Emma to leave the charismatic groups, she seemed reluctant to use the professional treatment which was recommended to her after the diagnostic consultation. She professed faith in providence, saying mental health professionals could potentially express God's grace, but never pursued any therapy.

Divine providence shows us the way forward, which can even be in the form of therapeutic help. God does not work in a supernatural way but through everyday life, also through lay people rather than priests.

Perhaps this was her way for rebelling against the priests who told her that treatment was a condition sine qua non for receiving the sacraments. Instead, she moved to a new town and completely changed her environment. She also found a compromise solution in the form of pastoral counseling. Emma said she liked her new spiritual director and accepted his strict rules regarding appointments and timing.

I met a young priest in the confessional. I asked him for so-called spiritual direction and he agreed. I felt obliged to show him this [diagnostic] report and he wasn't scared [that I was possessed]. I was surprised by his maturity and willingness to serve other people. This priest… he treats me completely differently. He sticks to our arrangements, which is very cool. For example, as time passes and we are about to end… we start punctually at 4:00 p.m. and as 4:45 is approaching, he nicely sums up what we have talked about. He teaches me about boundaries.

Discussion

Emma has a history of problems relating to attachment, emotional regulation and self-image indicating features of a personality disorder. She also reported somatoform symptoms accompanied by alterations in consciousness. Her ‘attacks' were not only limited to religious rituals or other situations associated with the church but also occurred outside the religious context. For this reason, PTD was an adequate diagnosis, despite her evident personality problems.

People reporting possession are a heterogenous group from the diagnostic perspective. Clinicians need to consider conditions other than PTD potentially valid categories, in particular: personality disorders (13), complex dissociative disorders or PTSD (20, 21, 54, 73) or psychosis (14). Analyzing stressful experiences, existing psychological conflicts and the pathways to the disorder can shed light on mechanisms behind alterations of consciousness and behavior, and potential gains from illness (4, 31). This was possible to see in our case study.

Exploring the complexity of ego-dystonic behavior may also reveal if possession-form presentations merely express conflicting and disowned emotions and needs, or reflect a more complex dissociative structure. In the former case, endorsement and identification with the possession can help people justify their shameful aggressive or sexual acts. In a similar way, people with false-positive DID use the learnt concept of alternative identities or parts to receive attention or express conflicting emotions (74). In a more fragmented psyche, however, the possessing agent can embody an autonomous dissociative part with a first-person perspective. Their degree of mental autonomy and complexity may differ—from simple ego-dystonic parts embodying particular ego states (e.g., rage), to fairly complex, characterful parts with their own sense of identity, motives, and memories.

According to ICD-11, the boundary between PTD and DID lies in the attribution of the possessing agent: external in PTD and not external in DID/Partial DID. There seems to be no scientific evidence for that distinction. Moreover, clinical observations indicate that DID patients experience their alternate identities as alien and ego-dystonic, therefore the external / internal attribution is not very clear in them (75).

We also share doubts about the validity of PTD. Its diagnostic criteria include both symptoms (changes in behavior and sense of identity accompanied by alterations in consciousness) and meaning which patients attribute to them. This way of formulating diagnostic criteria would rather justify treating PTD as a culture-bound syndrome. Whereas, culture shapes the way in which people express and interpret their symptoms, and possession by the goddess Kali, devil, or evil spirits in a Buddhist context may present itself differently, Ross et al. (53) postulate that there is an underlying dissociative pathology in people with culture-bound syndromes which should be carefully examined. This means that in making a diagnosis clinicians should focus on symptoms rather than ascribed meaning.

Further research is also necessary to assess the usefulness of a PTD diagnosis, as this category can have serious implications for patients, their families and spiritual community, and even healthcare providers. In those who use religious services, it can reinforce the belief in the supernatural causation of their symptoms, make them reluctant to use recommended treatment and overemphasize religious coping. Externalization of conflicts does not necessarily promote seeing and embracing unaccepted impulses as one's own. While this may be functional, it may block further development and be iatrogenic (13). Furthermore, the double meaning of “possession” (as a cultural and medical concept) makes it difficult for some specialists to think about their patients in strictly clinical terms. Subsequently, they consider “genuine possession” as a possible explanation for reported symptoms (12, 25, 26). Because of the religious connotations, we recommend to reconsider the name and diagnostic criteria of PTD. It might be more appropriate to use the 6B6Y category in ICD-11 (Other specified dissociative disorders) for people with this clinical presentation, similarly to DSM-5.

Feeling trapped between the cultural and medical notions of possession can influence the way mental health professionals collaborate with clergy in diagnosing and treating patients with possession-form presentations. For some, it may be difficult to maintain clear professional boundaries: identify and describe symptoms of clinical significance, formulate accurate diagnosis, and offer psychoeducation and treatment, at the same time, staying culturally sensitive and understanding the need for spiritual support sought by patients. The role of the clinician is not to exclude the spiritual causation of reported symptoms but to offer an alternative understanding of psychological conflicts and unmet needs.

Limitations and Further Directions

IPA studies, being focused on how people experience phenomena and meaning-making, are naturally limited to small samples or even case studies. Care should be taken in drawing conclusions from such qualitative studies and further research using rigorous methodology is required to explore problems and illness behavior in people with possession-form presentations. More studies are necessary comparing PTD with other dissociative disorders (Partial DID and DID), analyzing in particular different clusters of symptoms and emotional regulation. Longitudinal studies exploring the development of symptoms and help-seeking pathways, and meaning attributed to the medical and folk diagnoses are also recommended.

Conclusions

Our review of literature shows that PTD requires further scientific evidence to remain a valid clinical diagnosis. Thorough diagnostic assessments should be applied to people reporting possession-form presentations, not only exploring their phenomenological features, but also accompanying problems and symptoms. Use of the term “possession” by mental health professionals is also burdened with social consequences. It can reinforce patients' beliefs about the supernatural causation of problems and affect help-seeking. We thus stipulate that the “Other” specified dissociative disorders category in ICD-11 could be more appropriate for people with this clinical presentation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Polish law regarding medical history and the guidelines of the Ethical Board do not allow distributing the transcripts of the interview or psychiatric assessment. This material contains patient's identifiable information. Furthermore, transcripts include about 70 pages of text in Polish which cannot be translated and edited to mask patient's details. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to aXBpZXRraWV3aWN6QHN3cHMuZWR1LnBs.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical Review Board at the SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

IJP developed the concept of this research, collected clinical data, analyzed literature and transcripts, and wrote manuscript. UK transcribed interviews and helped in literature review and data analysis. RT performed psychiatric assessment, participated in analyzing interviews, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the National Science Centre, Poland: 2017/25/B/HS6/01025.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Cardeña E, van Duijl M, Weiner LA, Terhun DB. Possession/trance phenomena. In: Dell PE, O'Neil JA,. Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders: DSM-V and Beyond. 1st ed. (2009). p. 171–81. London: Routledge.

2. Van Duijl M, Kleijn W, de Jong J. Are symptoms of spirit possessed patients covered by the DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria for possession trance disorder? A mixed-method explorative study in Uganda. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2013) 48:1417–30. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0635-1

3. Khalifa N, Hardie T. Possession and jinn. J R Soc Med. (2005) 98:351–3. doi: 10.1177/014107680509800805

4. Somer E. Paranormal and dissociative experiences in Middle-Eastern Jews in Israel: diagnostic and treatment dilemmas. Dissociation. (1997) 10:174–81.

5. Igreja V, Dias-Lambranca B, Hershey DA, Racin L, Richters A, Reis R. The epidemiology of spirit possession in the aftermath of mass political violence in Mozambique. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 71:592599. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.024

6. Hanwella R, de Silva V, Yoosuf A, Karunaratne S, de Silva P. Religious beliefs, possession states, and spirits: three case studies from Sri Lanka. Case Rep Psychiatry. (2012) 1–3. doi: 10.1155/2012/232740

7. Szabo CP, Jonsson G, Vorster V. Dissociative trance disorder associated with major depression and bereavement in a South African female adolescent. Austral N Zeal J Psychiatry. (2005) 39:423. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01593.x

8. Kianpoor M, Rhoades JGF. Djinnati, a possession state in Baloochistan, Iran. J Trauma Pract. (2006) 4:147155. doi: 10.1300/J189v04n01_10

9. Mercer JA. The Protestant child, adolescent, and family. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin. (2004) 13:161–81. doi: 10.1016/S1056-4993(03)00074-9

10. Pietkiewicz IJ, Lecoq-Bamboche M. Exorcism leads to reenactment of trauma in a Mauritian Woman. J Child Sex Abus. (2017) 26:970–92. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2017.1372837

11. Pietkiewicz IJ, Lecoq-Bamboche M, Van der Hart O. Cultural pathoplasticity in a Mauritian woman with possession-form presentation: is it dissociative or not? Eur J Trauma Dissoc. (2020) 4:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2019.100131

13. Pietkiewicz IJ, Kłosińska U, Tomalski R, Van der Hart O. Beyond dissociative disorders: a qualitative study of Polish catholic women reporting demonic possession. Eur J Trauma Dissoc. (2021) 5:01–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100204

14. Pietkiewicz IJ, Kłosińska U, Tomalski R. Delusions of possession and religious coping in schizophrenia: a qualitative study of four cases. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:628925. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.628925

15. Boddy J. Wombs and Alien Spirits: Women, Men, and the Zar Cult in Northern Sudan. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press (1989).

16. Bourguignon E. Religion, Altered States of Consciousness, and Social Change. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press (1973).

17. World Health Organization. (2022). 6B63 Possession Trance Disorder. Available online at: https://icd.who.int/dev11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f1374925579 (accessed March 07, 2022).

18. American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

19. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

20. Delmonte R, Lucchetti G, Moreira-Almeida A, Farias M. Can the DSM-5 differentiate between nonpathological possession and dissociative identity disorder? A case study from an Afro-Brazilian religion. J Trauma Dissoc. (2016) 17:322–37. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2015.1103351

21. Pietkiewicz IJ, Kłosińska U, Tomalski R. Polish Catholics attribute trauma-related symptoms to possession: qualitative analysis of two childhood sexual abuse survivors. J Child Sexual Abuse. (2022). doi: 10.1080/10538712.2022.2067094

22. Van der Hart O, Lierens R, Goodwin J. Jeanne Fery: a sixteenth-century case of dissociative identity disorder. J Psychohistory. (1996) 24:8.

23. Martinez A. A case of spirit possession and glossolalia. Cult Med Psychiatry. (1999) 23:333–48. doi: 10.1023/A:1005504222101

24. Van Duijl M, Nijenhuis E, Komproe IH, Gernaat HBPE, De Jong J. Dissociative symptoms and reported trauma among patients with spirit possession and matched healthy controls in Uganda. Cult Med Psychiatry. (2010) 34:380400. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9171-1

25. Bayer RS, Shunaigat WM. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of possessive disorder in Jordan. Neurosciences. (2002) 7:46–9.

26. Hale AS, Pinninti NR. Exorcism-resistant ghost possession treated with clopenthixol. Br J Psychiatry. (1994) 165:386–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.3.386

27. Khan ID, Sahni AK. Possession syndrome at high altitude (4575 m/15000 ft). Kathmandu Univ Med J. (2013) 11:253255. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v11i3.12516

28. Bakhshani NM, Hosseinbore N, Kianpoor M. Djinnati syndrome: symptoms and prevalence in rural population of Baluchistan (southeast of Iran). Asian J Psychiatr. (2013) 6:566–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.09.012

29. Bayer RS, Shunaigat WM. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of possessive disorder in Jordan. Neurosciences. (2002) 7:46–9.

30. Butt A, Beig A, Dogar F, Islam J, Abdi S. Frequency of anxiety and depression in dissociative trance (possession) disorder. J Fatima Jinnah Med Univ. (2021) 15:72–5. doi: 10.37018/AUMO3440

31. Castillo RJ. Spirit possession in South Asia, dissociation or hysteria? Part 2: case histories. Cult Med Psychiatry. (1994) 18:141–62. doi: 10.1007/BF01379447

32. Chand SP, Al-Hussaini AA, Martin R, Mustapha S, Zaidan Z, Viernes N, et al. Dissociative disorders in the Sultanate of Oman. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2000) 102:185–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102003185.x

33. Chaturvedi SK, Desai G, Shaligram D. Dissociative disorders in a psychiatric institute in India-a selected review and patterns over a decade. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2010) 56:533–9. doi: 10.1177/0020764009347335

34. Das PS, Saxena S. Classification of dissociative states in DSM-III-R and ICD-10 (1989 draft). A study of Indian out-patients. Br J Psychiatry. (1991) 159:425–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.3.425

36. Etsuko M. The interpretations of fox possession: illness as metaphor. Cult Med Psychiatry. (1991) 15:453–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00051328

37. Ferracuti S, Sacco R. Dissociative trance disorder: clinical and Rorschach findings in ten persons reporting demon possession and treated by exorcism. J Pers Assess. (1996) 66:525–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6603_4

38. Ferracuti S, DeMarco MC. Ritual homicide during dissociative trance disorder. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. (2004) 48:59–64. doi: 10.1177/0306624X03257516

39. Freed RS, Freed SA. Ghost illness in a North Indian village. Soc Sci Med. (1990) 30:617–23. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90160-T

40. Gaw AC, Ding QZ, Levine RE, Gaw HF. The clinical characteristics of possession disorder among 20 Chinese patients in the Hebei province of China. Psychiatr Serv. (1998) 49:360–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.3.360

41. Guenedi AA, Al Hussaini AA, Obeid YA, Hussain S, Al-Azri F, Al-Adawi S. Investigation of the cerebral blood flow of an Omani man with supposed “spirit possession” associated with an altered mental state: a case report. J Med Case Rep. (2009) 5:9325. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-9325

42. Khattri JB, Goit BK, Thakur RK. Prevalence of dissociative convulsions in patients with dissociative disorder in a tertiary care hospital: a descriptive cross-sectional study. J Nepal Med Assoc. (2019) 57:320–2. doi: 10.31729/jnma.4640

43. Khoe HCH, Gudi A. Case report: an atypical presentation of panic disorder masquerading as possession trance. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 12:819375. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.819375

44. Khoury NM, Kaiser BN, Keys HM, Brewster ART, Kohrt BA. Explanatory models and mental health treatment: is vodou an obstacle to psychiatric treatment in rural Haiti? Cult Med Psychiatry. (2012) 36:514534. doi: 10.1007/s11013-012-9270-2

45. Mattoo SK, Gupta N, Lobana A, Bedi B. Mass family hysteria: a report from India. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2002) 56:643–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.01069.x

46. Neuner F, Pfeiffer A, Schauer-Kaiser E, Odenwald M, Elbert T, Ertl V. Haunted by ghosts: prevalence, predictors and outcomes of spirit possession experiences among former child soldiers and war-affected civilians in Northern Uganda. Soc Sci Med. (2012) 75:548–54. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.028

47. Ng BY. Phenomenology of trance states seen at a psychiatric hospital in Singapore: a cross-cultural perspective. Transcult Psychiatry. (2000) 37:560–79. doi: 10.1177/136346150003700405

48. Ng BY, Chan YH. Psychosocial stressors that precipitate dissociative trance disorder in Singapore. Austral N Zeal J Psychiatry. (2004) 38:426–32. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01379.x

49. Peltzer K. Nosology and etiology of a spirit disorder (Vimbuza) in Malawi. Psychopathology. (1989) 22:145–51. doi: 10.1159/000284588

50. Pereira S, Bhui K, Dein S. Making sense of 'possession states': psychopathology and differential diagnosis. Br J Hosp Med. (1995) 53:582–6.

51. Piñeros M, Rosselli D, Calderon C. An epidemic of collective conversion and dissociation disorder in an indigenous group of Colombia: its relation to cultural change. Soc Sci Med. (1998) 46:1425–8. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)10094-6

52. Prakash R, Singh LK, Bhatt N, Goyal N, Mishra B, Akhtar S. Possession states precipitated by nortriptyline. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2008) 42:432–3.

53. Ross CA, Schroeder E, Ness L. Dissociation and symptoms of culture-bound syndromes in North America: a preliminary study. J Trauma Dissoc. (2013) 14:224–35. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2013.724338

54. Sar V, Alioglu F, Akyüz G. Experiences of possession and paranormal phenomena among women in the general population: are they related to traumatic stress and dissociation? J Trauma Dissoc. (2014) 15:303–18. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2013.849321

55. Satoh S, Obata S, Seno E, Okada T, Morita N, Saito T, et al. A case of possessive state with onset influenced by ‘door-to-door' sales. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (1996) 50:313–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1996.tb00571.x

56. Saxena S, Prasad KV. DSM-III subclassification of dissociative disorders applied to psychiatric outpatients in India. Am J Psychiatry. (1989) 146:261–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.2.261

57. Schaffler Y, Cardeña E, Reijman S, Haluza D. Traumatic experience and somatoform dissociation among spirit possession practitioners in the dominican republic. Cult Med Psychiatry. (2016) 40:74–99. doi: 10.1007/s11013-015-9472-5

58. Schieffelin EL. Evil Spirit Sickness, the Christian disease: the innovation of a new syndrome of mental derangement and redemption in Papua New Guinea. Cult Med Psychiatry. (1996) 20:1–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00118749

59. Sethi S, Bhargava SC. Mass possession state in a family setting. Transcult Psychiatry. (2009) 46:372–4. doi: 10.1177/1363461509105828

60. Somasundaram D, Thivakaran T, Bhugra D. Possession states in Northern Sri Lanka. Psychopathology. (2008) 41:245–53. doi: 10.1159/000125558

61. Somer E. Paranormal and dissociative experiences in Middle Eastern Jews in Israel: diagnostic and treatment dilemmas. Dissociation. (1997) 10:174–81.

62. Trangkasombat U, Su-umpan U, Churujikul V, Prinksulka K. Epidemic dissociation among school children in southern Thailand. Dissociation. (1995) 8:130–41. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-03674-001

63. Witztum E, Buchbinder JT, van der Hart O. Summoning a punishing angel: treatment of a depressed patient with dissociative features. Bull Menninger Clin. (1990) 54:524–37.

64. Witztum E, Grisaru N, Budowski D. The 'Zar' possession syndrome among Ethiopian immigrants to Israel: cultural and clinical aspects. Br J Med Psychol. (1996) 69:207–25. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1996.tb01865.x

65. During EH, Elahi FM, Taieb O, Moro MR, Baubet T. A critical review of dissociative trance and possession disorders: etiological, diagnostic, therapeutic, and nosological issues. Can J Psychiatry. (2011) 56:235–42. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600407

66. Hecker T, Braitmayer L, van Duijl M. Global mental health and trauma exposure: the current evidence for the relationship between traumatic experiences and spirit possession. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2015) 6:29126. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.29126

67. Smith JA, Osborn M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Smith J, editor. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. London: Sage (2008). p. 53–80.

68. Pietkiewicz I, Smith JA. A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychol J. (2014) 20:7–14. doi: 10.14691/CPPJ.20.1.7

69. Pietkiewicz IJ, Helka AM, Tomalski R. Validity and reliability of the Polish online and pen-and-paper versions of the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaires (SDQ-20 and PSDQ-5). Eur J Trauma Dissoc. (2019) 3:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2018.05.002

70. Pietkiewicz IJ, Hełka AM, Tomalski R. Validity and reliability of the revised Polish online and pen-and-paper versions of the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DESR-PL). Eur J Trauma Dissoc. (2019) 3:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2019.02.003

73. Ross CA. Possession experiences in dissociative identity disorder: a preliminary study. J Trauma Dissoc. (2011) 12:393–400. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2011.573762

74. Pietkiewicz IJ, Bańbura-Nowak A, Tomalski R, Boon S. Revisiting false-positive and imitated dissociative identity disorder. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:637929. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.637929

Keywords: Possession Trance Disorder, dissociation, assessment, religious coping, exorcism

Citation: Pietkiewicz IJ, Kłosińska U and Tomalski R (2022) Trapped Between Theological and Medical Notions of Possession: A Case of Possession Trance Disorder With a 3-Year Follow-Up. Front. Psychiatry 13:891859. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.891859

Received: 08 March 2022; Accepted: 04 May 2022;

Published: 26 May 2022.

Edited by:

Clare Margaret Eddy, Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Pietkiewicz, Kłosińska and Tomalski. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Igor J. Pietkiewicz, aXBpZXRraWV3aWN6QHN3cHMuZWR1LnBs

Igor J. Pietkiewicz

Igor J. Pietkiewicz Urszula Kłosińska

Urszula Kłosińska Radosław Tomalski

Radosław Tomalski