94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Psychiatry, 24 March 2022

Sec. Addictive Disorders

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.862208

This article is part of the Research TopicClinical Practices of Co-occurring Psychiatric and Addictive DisordersView all 5 articles

Jan Dieris-Hirche1*

Jan Dieris-Hirche1* Bert Theodor te Wildt1,2

Bert Theodor te Wildt1,2 Magdalena Pape1

Magdalena Pape1 Laura Bottel1

Laura Bottel1 Toni Steinbüchel1

Toni Steinbüchel1 Henrik Kessler1

Henrik Kessler1 Stephan Herpertz1

Stephan Herpertz1

Introduction: Evidence from clinical studies on quality of life (QoL) in patients suffering from internet use disorders (IUD) is still limited. Furthermore, the impact of additional mental comorbidities on QoL in IUD patients has rarely been investigated yet.

Materials and Methods: In a cross-sectional clinical study 149 male subjects were analyzed for the presence and severity of an IUD as well as other mental disorders by experienced clinicians. The sample consisted of 60 IUD patients with and without comorbid mental disorders, 34 non-IUD patients with other mental disorders, and 55 healthy participants. Standardized clinical interviews (M.I.N.I. 6.0.0) and questionnaires on IUD symptom severity (s-IAT), QoL (WHOQOL-BREF), depression and anxiety symptoms (BDI-II and BAI), and general psychological symptoms (BSI) were used.

Results: Internet use disorder patients showed significantly reduced QoL compared to healthy controls (Cohen’s d = 1.64–1.97). Furthermore, IUD patients suffering from comorbid mental disorders showed significantly decreased levels of physical, social, and environmental QoL compared to IUD patients without any comorbidity (p < 0.05–0.001). Multiple linear regression analyses revealed that low levels of psychological, social and environmental QoL were mainly predicted by symptoms of depression. IUD factors were only significant predictors for the social and physical QoL.

Discussion: Internet use disorder patients with comorbid mental disorder reported the lowest QoL. Depression symptom severity was the most significant predictor of low QoL in IUD. Strategies to reduce depressive symptoms should therefore be considered in IUD treatment to increase patients’ QoL.

Internet use disorder (IUD) is a general term defined as an excessive and uncontrolled use of Internet applications in terms of an online behavioral addiction. It includes both excessive online-gaming (as the largest category) and non-gaming internet activities, i.e., online shopping, pornography use, social network use, and general Internet use (1). Consistent with the inclusion of (Internet) Gaming Disorder (IGD) as the first IUD in the ICD-11 (2), many researchers switched from using the term Internet addiction to IUD to be in accordance with the terminology used in the upcoming ICD-11 (1).

Internet use disorder has increased in the last decades with worldwide prevalence rates ranging between 2.6% in northern and western Europe and 10.9% in the Middle East; the average global prevalence is estimated at a level of 6.0% (3). In German populations, the IUD prevalence rates range between 1.2 and 3.1% (4–8). However, most studies of IUD prevalence were conducted using screening questionnaires, which increases the risk of false positives or high prevalence. Consequently, studies on clinical samples using standardized diagnostic examinations by experts are significant, although the samples are often smaller.

Individuals with IUD show a persistent pattern of Internet use that is characterized by impaired control regarding the onset, intensity and duration of usage (2). The increased priority given to Internet activities leads to neglect of daily activities and life interests, and IUD is associated with social, physical and mental burden (9, 10). In addition, high comorbidity with psychiatric disorder has been reported, especially depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, substance use disorders and impulse control disorders (11–16). Although representative studies often report a balanced gender distribution (5, 6, 17, 18), it is predominantly male IUD patients who come to clinics for therapy (19, 20).

So far, quality of life (QoL) in problematic or pathological Internet use was examined in studies surveyed in non-clinical contexts, such as high school, college students, or in the general population (21–25). Evidence from studies of QoL in IUD patients in a clinical context is still limited (26). The comparison of QoL between IUD patients and patients with other mental disorders has only been considered in online surveys, but not in clinical populations (27). Hence, the current study investigates the impairment of QoL in a clinical group of male IUD patients using high methodological standards, in particular standardized clinical interviews by experienced clinicians.

The research questions (RQ) and hypotheses (H) were:

(1) RQ1: Is there any impairment at all in QoL domains of patients with IUD (compared to healthy control group)? H1: We expected that IUD patients show lower levels of QoL compared to healthy controls.

(2) RQ2: If so, how do IUD patients with comorbid mental disorders differ in QoL from IUD patients without comorbid mental disorders? H2: We expect greater QoL impairment in IUD patients with comorbidities.

(3) RQ3: Considering IUD patients, what factors predict low levels of QoL in different domains? H3: We expect that IUD factors are significant predictors of QoL.

(4) RQ4: Do IUD patients’ QoL differ from patients with other (non-IUD) mental disorders? If so, in which way?

The trial was conducted as a cross-sectional study on men only. The limitation to male IUD patients resulted from the fact that IUD treatment seekers were almost exclusively men. Between 2016 and 2017 a total of n = 60 male IUD patients according to DSM-5 criteria (experimental group, EG) were recruited in an IUD specialized outpatient clinic at a university hospital in Germany. All patients were individuals who came to the clinic on their own initiative to seek diagnosis and treatment. The patients were examined for the presence of an IUD as well as other mental disorders by experienced clinicians using standardized clinical interviews. In total, 31 IUD patients without other comorbid mental disorders (EG1) and 29 IUD patients with at least one further comorbid mental disorder (EG2) were recruited and diagnosed. Furthermore, two age-matched male control groups (CG1 and CG2) were recruited. CG1 was 1:1 matched with the EG, consisted of 57 healthy male participants, and was recruited via an advertisement in local newspapers. CG2 was 1:1 matched to EG1 and EG2, consisted of 34 male non-IUD patients with different mental disorders (CG2), and were also recruited at the same outpatient clinic in Germany. In order to obtain standardized information about the mental disorder present, both control groups were also examined using the same diagnostic procedure. Thus, a total of 151 subjects were finally included in the study. The inclusion criteria were: legal age, mastery of the German language, presence of an IUD (EG1 and EG2), presence (CG2) or absence (CG1) of other mental disorders. The exclusion criteria for EG and CG2 were: psychosis or delusional disorder, bipolar disorder, complex post-traumatic stress disorder and acute substance addiction (without tobacco). These mental disorders were excluded as they were assumed to be so severe, acute or complex and thus lead to a confounding of the effects of the study. The exclusion criterium for CG1 was the presence of any mental disorder. In accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 1983, the Ethics Committee of the Ruhr-University Bochum approved the study (registration number: 15-5155). All participants were informed about the study prior to participation and provided written informed consent.

Mental disorders were diagnosed by the clinical neuropsychiatric interview M.I.N.I. adapted to the German language, version 6.0.0 (28). The M.I.N.I. interview is based on the international classification systems ICD-10 and DSM-4. In addition, a structured clinical interview was conducted for diagnosing IUD that was based on the research criteria for online computer game addiction according to DSM-5 (29). These criteria have been adapted for different types of IUD (e.g., cybersex, social media, online streaming). IUD was diagnosed if at least five of the nine DSM-5-criteria were present over a 12-month period.

The Short version of the Internet Addiction Test (s-IAT) (30) was used to measure the IUD symptom severity. The self-report questionnaire consists of 12 items, which are rated on a 5-point-Likert scale from 1 (“rarely”) to 5 (“always”) with a total score range from 12 to 60 points. Higher scores reflecting higher IUD symptom severity. Sum scores above the cut-off of 37 points indicate pathological Internet use. For this study, Cronbach’s α = 0.94.

The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF (31, 32) was used to assess quality of life. The WHOQOL-BREF creates four domain scores using 24 items: a 7-item “physical health” domain, a 6-item “psychological health” domain, a 3-item “social relationships” domain, and an 8-item “environment” domain. Transformed domain scores resulted in a 0–100 scale in which higher scores indicate higher QoL. WHOQOL-BREF has been validated in dozens of countries and languages, and among healthy and clinical populations (33). For this study, Cronbach’s α for the domains ranged between 0.60 and 0.83.

The Beck’s Depressions Inventory, revised (BDI-II) (34, 35) was used to measure depression symptom severity. It consists of 21 items representing 21 symptoms of depression, which can be rated from 0 to 3 in terms of intensity based on the last 7 days. The total score ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity. For this study, Cronbach’s α = 0.94.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) measures anxiety with a focus on somatic symptoms of anxiety that was developed to discriminate between anxiety and depression (36). Responses are rated in 21 items on a 4-point Likert scale and range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely). The total score ranges from 0 to 63 with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity. For this study, Cronbach’s α = 0.92.

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) is an abbreviated form of the revised Symptom Check List (SCL-90-R) and includes 53 items to assess psychological symptom burden in adults (37, 38). It includes nine subscales and a global severity score (GSI) that is used to assess basic psychological distress. For this study, Cronbach’s α for the subscales ranged between 0.78 and 0.90.

Analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS statistics for Macintosh (Version 26.0, Armonk, NY, United States: IBM Corp.) and G*Power for Macintosh, version 3.1 (39). Normal distribution was estimated using Q–Q plots. Bootstrapping method [1,000 samples, bias corrected and accelerated (BCa)] was used in analyses for variables that were obviously not normally distributed. To compare group differences, chi-square distribution for categorical variables (using effect size φ), independent t-test for metrically scaled variables (using effect size d) as well as univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc test (using effect size η2) was used. Multiple linear regressions (stepwise) were used to estimate the relationship between multiple independent variables and quality of life domains as dependent variable (using effect size f2). Associations between age, IUD symptoms, psychiatric symptoms and quality of life were analyzed using bootstrapped Pearson correlations and partial correlations controlling for confounding variables. The following effect sizes were calculated following Cohen (40): Eta squared η2 = 0.01 small, η2 = 0.06 moderate, η2 = 0.14 large effect. Cohen’s d = 0.20 small, d = 0.50 moderate, and d = 0.80 large effect. Phi-coefficient φ = 0.10 small, φ = 0.30 moderate, φ = 0.50 large effect. Cohen’s f2 = 0.02 small, f2 = 0.15 moderate, f2 = 0.35 large effect.

A recently published study conducted on college students to examine quality of life and Internet addiction showed significant differences between the two groups “with Internet addiction” and “without Internet addiction” with an effect size of d = 0.69, 95% CI [0.44, 0.96] (41). An a-priori power analysis was performed for the independent sample t-test using this estimated effect size d = 0.69. It indicated that a sample of 34 people per group (total N = 68) would be needed to reach a power (1 − β error probability) = 0.80 using α = 0.05. A post-hoc t-test analysis conducted with our final results (60 IUD patients, 55 healthy controls, effect size for QoL environment d = 1.64) indicated a power > 99% (2-sided). Furthermore, a post-hoc power analysis for each linear regression was conducted using n = 60 IUD participants, the effect sizes f2 [calculated using the formula f2 = R2/1 – R2 (40)], α = 0.05, and nine tested predictors. All these analyses showed a power > 99%.

Boxplots and histograms were used to identify extreme outliers for the variables BDI, BAI, s-IAT, and all QoL domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. In total, n = 2 extreme outliers were excluded from the healthy control group (CG1) due to extreme BDI-2 scores. The final total number of analyzed participants consisted of n = 149 subjects, including 31 IUD patients without comorbidity (EG1), 29 IUD patients with comorbidity (EG2), 55 healthy control subjects (CG1) and 34 patients with other mental disorders (CG2).

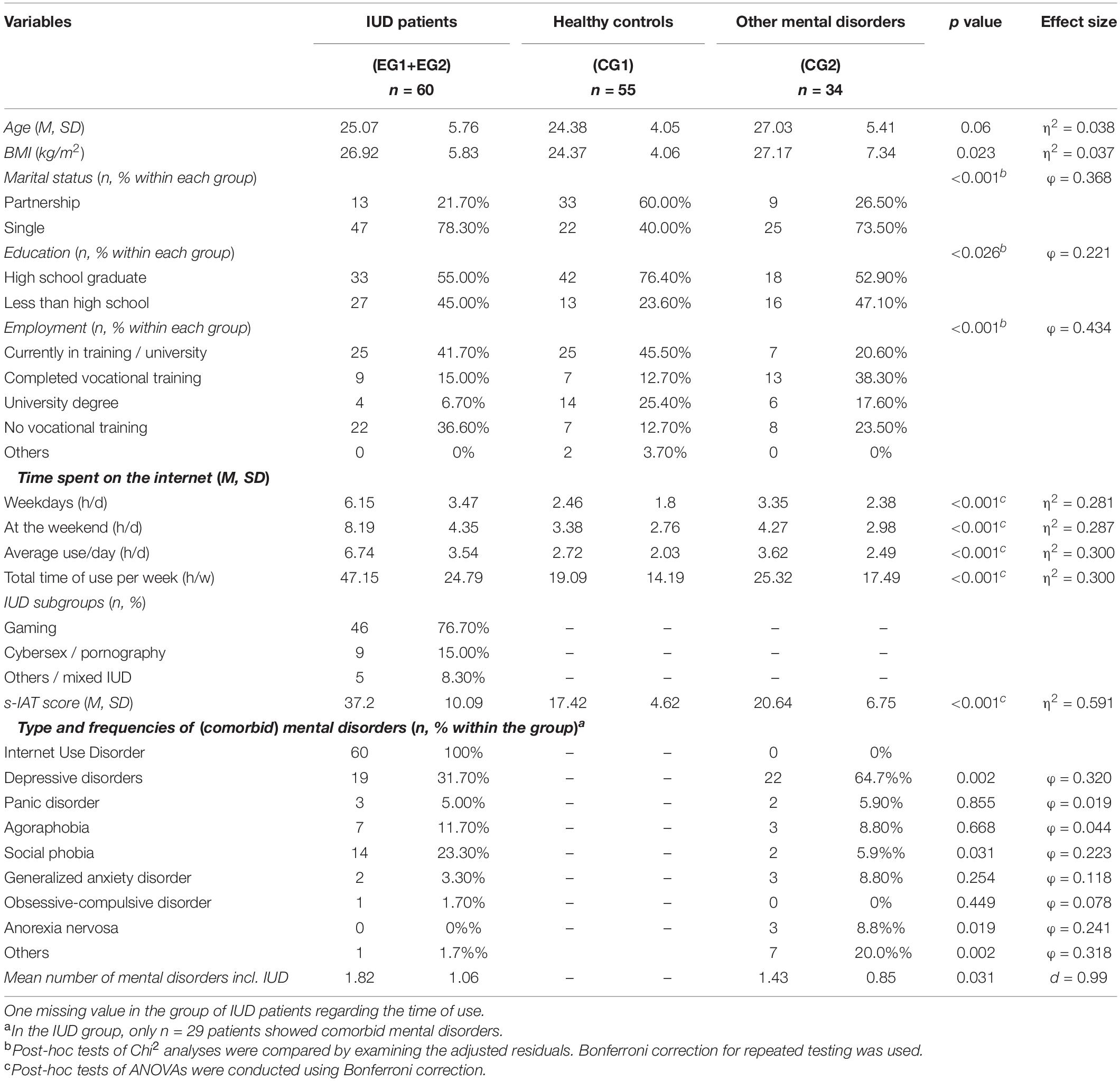

Group differences on sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidity, and Internet use characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Group differences on sociodemographic characteristics and internet use disorder (IUD) attributes.

The first step was to determine whether patients with IUDs had any impairment in QoL at all (RQ1). Bootstrapped independent-sample t-tests indicated significantly decreased QoL in all four domains (Cohen’s d = 1.64–1.97) for IUD patients (EG) compared to the healthy controls (CG1) (see Table 2). On the standardized scale between 0 and 100, IUD patients thus indicated a 48.9% decreased QoL in social relations compared to the CG1, followed by the psychological (decreased by 36.2%), physical (decreased by 29.8%), and environmental (decreased by 25.6%) domain. The global difference in QoL across all four domains was 35.1% as compared to the healthy CG1. H1 could thus be confirmed.

After analyzing that IUD patients generally showed a reduction in QoL, the group was divided into EG1 (n = 31 IUD patients without other mental comorbidity) and EG2 (n = 29 IUD patients with at least one other comorbid mental disorder) to examine the impact of the mental comorbidity on QoL in IUDs (RQ2). The two groups of IUD patients had approximately the same mean age (25.75 vs. 24.34 years, p = 0.352), and the distribution of IUD subtypes also showed no significant difference (77.4% video games vs. 75.9% video games, p = 0.847). They also did not differ significantly in body mass index (26.8 vs. 27.0 kg/m2, p = 0.925).

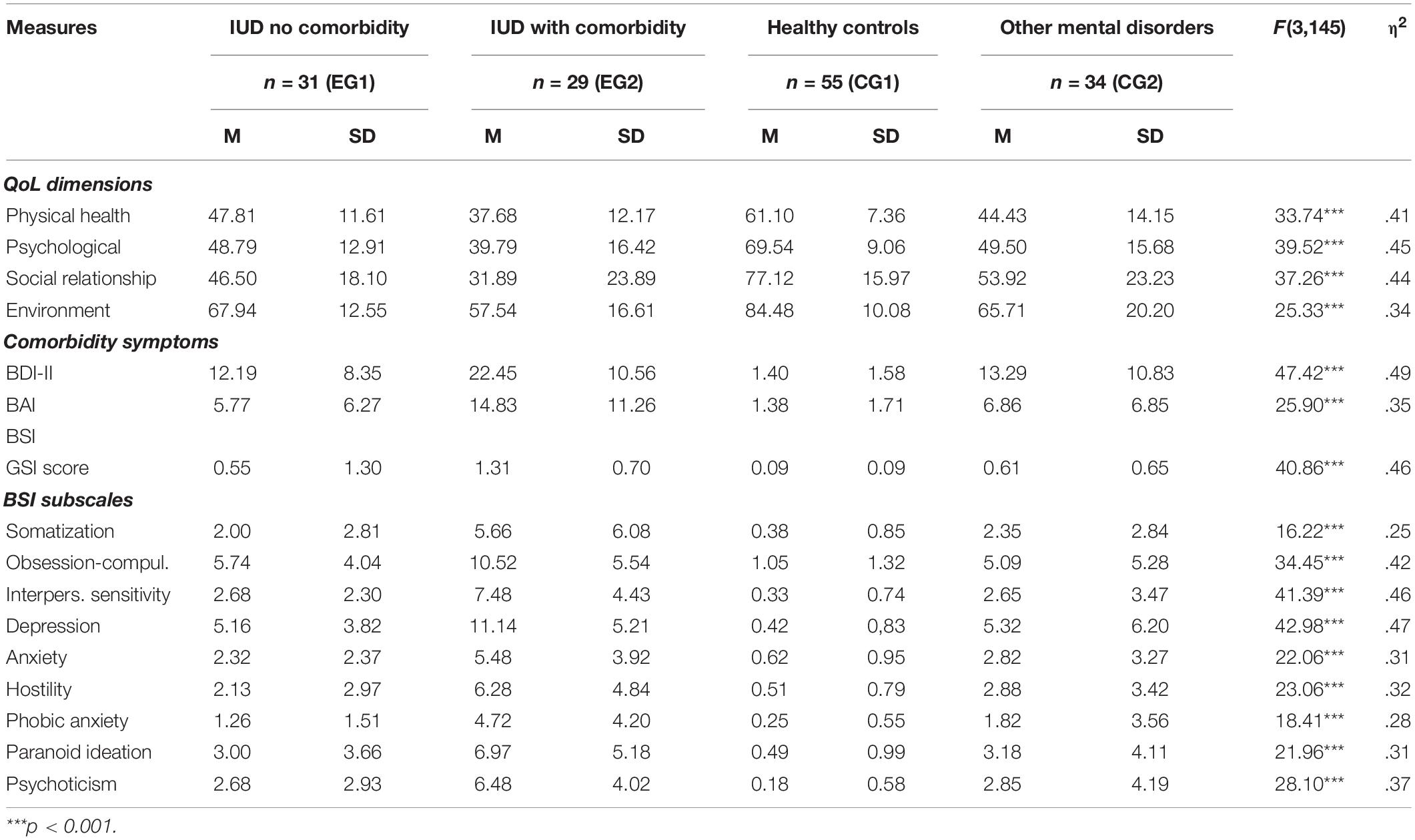

With reference to RQ4, EG1 and EG2 were additionally compared with the CG1 (n = 55) and CG2 (n = 34). A bootstrapped one-way between-group ANOVA was conducted with the four QoL domains, BAI, BSI, and BDI-II as dependent variables. The ANOVA indicated significant group differences at the p < 0.001 level in all QoL domains and in all scales of psychological symptoms (BDI-II, BAI, BSI) regarding the four study groups (effect sizes η2 = 0.25–0.49; see Table 3).

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and one-way analyses of variance in quality of life (QoL) and comorbidity: comparison of study groups.

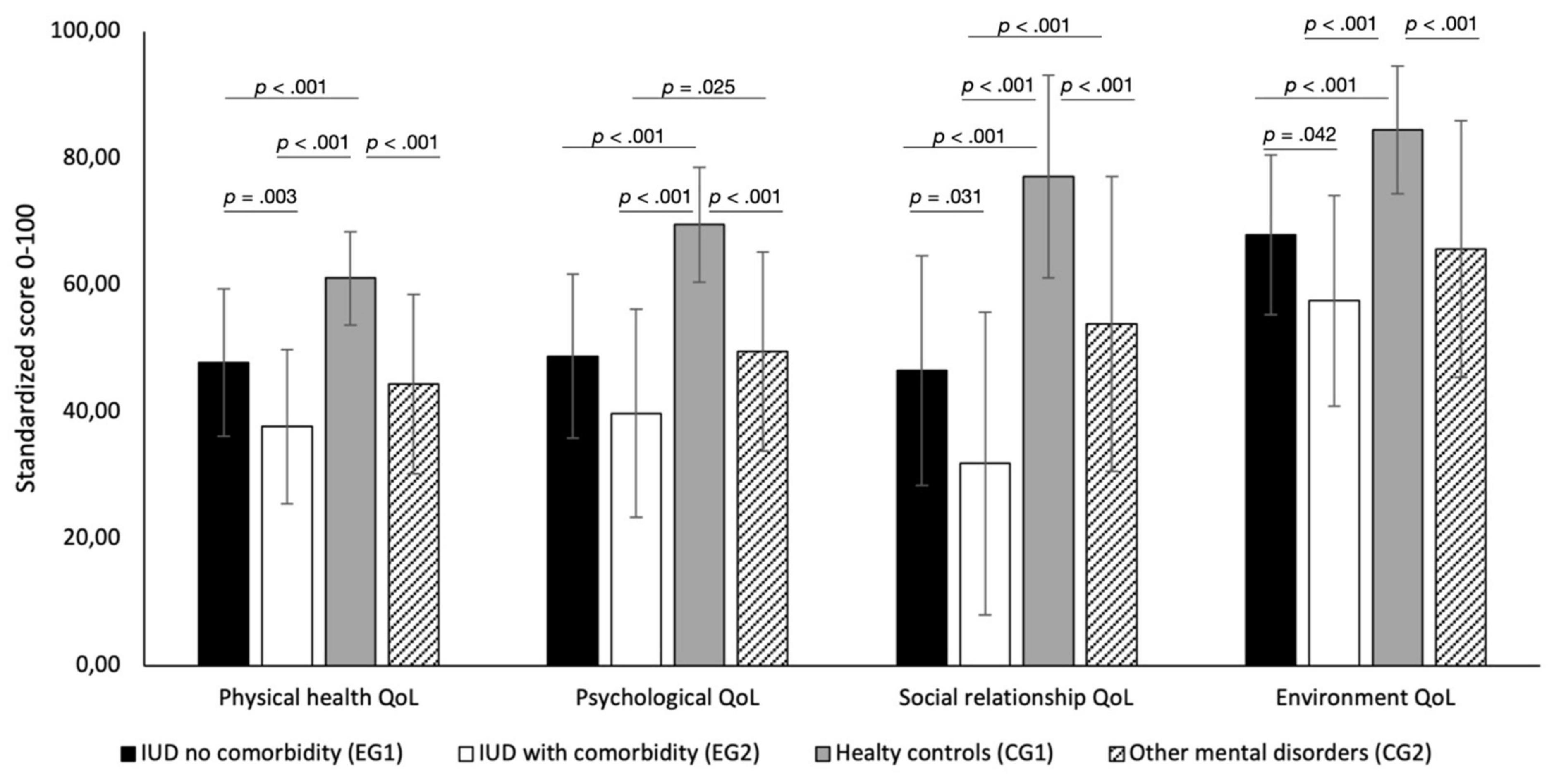

Post-hoc comparison with Bonferroni correction for the QoL domains indicated a constant pattern (see Figure 1) in all QoL domains with mostly significant differences (with the exception of the psychological domain) between EG1 and EG2. H2 could thus be confirmed. Further, we found significant differences in QoL domains between EG1 and CG1, and significant differences between CG1 and CG2. EG1 and CG2 did mostly not differ significantly in all QoL domains. In summary, EG2 showed the lowest score across all QoL domains. Thus, IUD patients with comorbid mental disorders (EG2) indicated 20.9% lower QoL compared to IUD patients without any comorbid mental disorders (EG1) considering all four QoL domains. In addition, EG2 patients also showed a 21.8% lower QoL compared to CG2 patients. Consequently, EG1 patients showed comparable QoL to CG2 patients. The healthy CG1 reported the highest QoL, as expected. A similar pattern was found in the post-hoc analyses (with Bonferroni correction) for the BDI, BAI, all BSI scales including the GSI (see Table 3, detailed post-hoc data not shown).

Figure 1. Levels of the 4 quality of life (QoL) dimensions: physical domain, psychological domain, social relations domain, environment domain. Post-hoc tests for the group differences between EG1, EG2, CG1, and CG2 are shown. Only the significant p values are shown.

In the bootstrapped correlation analysis for the EG (n = 60 IUD patients), highly significant positive associations were found between IUD symptoms (s-IAT score) on the one hand and depressive symptoms [r(58) = 0.51, p < 0.01], anxiety [r(58) = 0.42, p < 0.01] and general psychological distress [r(58) = 0.52, p < 0.01] on the other. Furthermore, significant negative correlations with quality of life were found for the physical domain [r(58) = −0.49, p < 0.01], the psychological domain [r(58) = −0.45, p < 0.01], and the environmental domain [r(58) = −0.27, p < 0.05]. However, when controlling for depression (BDI Score) using partial correlation, the correlations between IUD symptoms, psychological symptoms, and QoL domains mostly lost their significance (data not shown).

Four stepwise multiple regressions were conducted within the IUD sample (n = 60) to test which variables can predict each of the four QoL domain (RQ3). The following independent variables were included: IUD symptom severity (s-IAT score), average time spent on the Internet (hours/week), depression symptoms (BDI score), anxiety symptoms (BAI score), global impairment due to psychological symptoms (BSI GSI score), age, partnership (yes vs. no), education (high vs. lower), employment status (no vocational training vs. in training/finished degree/others), the body mass index (BMI), and numbers of mental disorders. The standardized scores for each of the four QoL domains were used as dependent variables.

The stepwise regression for the QoL domain physical health indicated that only the BSI score (β = −0.464, p < 0.001) and the s-IAT score (β = −0.256, p < 0.040) were significant predictors explaining 40.3% of the variance, R2 = 0.403, F(1,56) = 18.55, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.675. The psychological domain of QoL was significantly predicted by only the BDI score (β = −0.850, p < 0.001) and a missing of vocational training (β = −0.315, p < 0.001), R2 = 0.675, F(1,56) = 57.12, p < 0.001, f2 = 2.07. In contrast, the QoL domain social relationship was significantly predicted by both BDI score (β = −0.354, p = 0.006) and time spent on the Internet (β = −0.286, p = 0.025), R2 = 0.289, F(1,56) = 11.18, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.406. Finally, the QoL domain environment was significantly predicted only by BDI score (β = −0.611, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.373, F(1,56) = 33.35, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.594). In summary, H3 had to be partially rejected. The most powerful predictor for low QoL in IUD patients (in the psychological, social, and environmental domain) was the depression symptom severity. IUD factors only showed significantly predictive power in physical QoL (predicted by overall symptom burden and IUD severity) and social QoL (predicted by depressive symptoms and time of Internet use). Employment status (no vocational training) was a significant predictor of psychological QoL while all other socio-demographic variables, the numbers of mental disorders, and the body mass index were non-significant. All regression models reached large effect sizes f2 > 0.35.

It has been long debated whether IUDs are addictive disorders in terms of behavioral addictions, or if this concept merely over-pathologizes extensive Internet use and video gaming as an epiphenomenon of other mental disorders (42–45). The results of the present study support the current etiological understanding that IUD (particularly gaming disorder) is an independent mental disorder. IUD showed a discrete impact on QoL even if comorbid disorders have been ruled out using standardized diagnostics (hypothesis 1 confirmed). Furthermore, our study found a consistent QoL pattern: IUD patients showed significant impairments with high effect sizes in all QoL domains. Patients with IUDs had similarly high impairments in QoL as patients with non-IUD (mixed) mental disorders. Both patient groups were recruited at the same hospital, implying that no recruitment bias has to be expected. The combination of an IUD and another comorbid mental disorder decreased the QoL in all four domains by an additional 20% (hypothesis 2 confirmed). Particularly severe impairments in QoL were found in social and psychological QoL. It is known that there is a bidirectional relationship between depression and IUDs (46). Our study shows that the co-occurrence of IUD and depression may lead to a clinical relevance due to the lower levels of QoL, which should be considered a matter of focus in treatment planning.

When switching from the categorical (diagnosis according ICD-11) to the dimensional (degree of symptomatology) perspective, the results of the study showed a more differentiated situation. Contrary to our hypothesis, the regression analyses indicated that the impairment of QoL in psychological, social, and environment domains was mainly predicted by depressive symptoms. In contrast, IUD related factors showed a significant predictive role only in the psychological QoL domain (s-IAT score) and the social QoL domain (time spent on the Internet). The particular impact on the social QoL in patients with IUDs is consistent with earlier findings (9, 10) and therapeutic practice, and is therefore also an explicit diagnostic criterion in the DSM-5 (2). The physical QoL was predicted by global burden symptoms (BSI) and IUD severity (s-IAT). This result supports the recent knowledge about the complex association between IUD symptom severity and physical activity, which reports a reciprocal causality between IGD and the level of sport/exercise (47). The body mass index did not affect quality of life in our IUD sample. However, previous studies indicate that increased screen time and Internet use correlate with higher body weight and obesity (48, 49). Overall, the healthy group had the lowest BMI, the IUD patients and the patients with other mental disorders did not differ in BMI here. Thus, our study could not show any specific effect of media use on body weight.

The s-IAT score was mainly not a significant predictor of QoL when including depression symptoms in the regression models. These results were supported by the partial correlation between QoL domains and IUD symptomatology. Thus, when controlling for BDI score, all positive correlations between s-IAT, psychological symptoms, and QoL domains lost significance. In summary, hypothesis 3 had to be rejected in part. These findings may suggest that the association between IUD symptom severity and QoL could be meditated by depressive symptoms. A further mediation analysis on a sufficiently large sample could examine this more closely. On the other hand, the lower effect of IUD addiction symptoms on QoL could be explained by the clinical experience that many IUD patients feel a pleasurable relationship with video gaming and Internet usage. Video gaming, for example, is often experienced as self-esteem stabilizing and enjoyable, and thus often functions as an ultimate coping strategy against symptoms of depression (15). Therefore, IUD patients could underrate their problematic Internet use (s-IAT score), which could explain a loss of significance in the regression analyses. Many affected individuals are reluctant to give up computer gaming, but rather suffer from the social consequences and accompanying depressive symptoms. If they do not get “pressure” from their social environment (e.g., failed education, pressure from parents, unemployment), they would often describe life in the virtual world as (at least temporarily) very worthwhile and pleasurable. Therefore, further studies could assess the severity of IUD symptoms by patients and by their parents. Recent studies of adolescents with IGD and their parents suggested differences in assessment between affected subjects and their parents (50, 51).

The frequency of anxiety disorders was higher in the IUD group than in the patient control group. It cannot be excluded that the higher number of anxiety disorders could have an impact on quality of life. However, this is contradicted by our finding that anxiety symptoms (BAI) and number of mental disorders were not significant predictors in the regression.

The effect of depressive symptoms on QoL in IUD might have a clinical consequence. If depressive symptoms are relevant for the QoL in IUD patients, the integration of anti-depressive therapy strategies into IUD treatment could be considered to improve QoL. This might apply to psychopharmacological treatment, although evidence of efficacy is not strong (52, 53). A recent systematic review reported the antidepressants bupropion and escitalopram as successfully tested in some clinical studies (53). CBT-oriented IUD psychotherapy, on the other hand, show good efficacy in IUD patients, and already includes many anti-depressive therapeutic elements, e.g., activity planning and implementation, cognitive restructuring (54, 55).

The study is a cross-sectional study. Therefore, causal inferences can only be considered with caution. In addition, the sample sizes are limited, although the power analysis indicated a sufficient sample size. The strength of the study is that clinical patients were examined using standardized clinical interviews by experienced clinicians. However, multivariate analyses were calculated using self-assessment instruments. A further limitation is that only male IUD patients were studied and therefore also compared with only male control groups. The transmission to female IUD patients is therefore not possible, especially since women often use other Internet applications.

Male IUD patients showed a significantly lower QoL compared to age-matched healthy men supporting the clinical relevance of IUD. Furthermore, IUD patients with additional comorbid mental disorders even reported lower QoL than comparable non-IUD patients with other mental disorders. Depressive symptoms were a significant predictor of low QoL in IUD patients. Strategies to reduce depressive symptoms should therefore be considered in the treatment of IUD patients to improve QoL. Further IUD studies should examine QoL using self-assessment and additional assessments from relatives/partners, and should use mediation analysis. The physical and social QoL were most impaired und should be addressed more detailed. IUD patients often lose touch with their bodies, become overweight or do not exercise enough. This physical component should be further investigated, as many current therapeutic approaches do not yet include the stimulation of physicality.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Ruhr-University Bochum (no. 15-5155). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JD-H did the main conceptualization, conducted the statistical analysis, did the interpretation of the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BT and TS supported the conceptualization, designed and supervised the data collection, and did critical review, commentary, and revision. MP, LB, HK, and SH supported the interpretation of data and did critical review, commentary, and revision. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We wish to thank Ina Külpmann for the support with regard to the collection of the data.

1. Montag C, Wegmann E, Sariyska R, Demetrovics Z, Brand M. How to overcome taxonomical problems in the study of Internet use disorders and what to do with “smartphone addiction”? J Behav Addict. (2021) 9:908–14. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.59

2. World Health Organisation. Gaming Disorder, Predominantly Online. (2021). Geneva: World Health Organisation.

3. Cheng C, Li AY. Internet addiction prevalence and quality of (real) life: a meta-analysis of 31 nations across seven world regions. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2014) 17:755–60. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0317

4. Rehbein F, Kliem S, Baier D, Mößle T, Petry NM. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction. (2015) 110:842–51. doi: 10.1111/add.12849

5. Rumpf H-J, Meyer C, Kreuzer A, John U, Merkeerk G-J. Prävalenz der Internetabhängigkeit (PINTA). Bericht an das Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. (2011) 31:12.

6. Bischof G, Bischof A, Meyer C, John U, Rumpf H-J. Prävalenz der Internetabhängigkeit–Diagnostik und Risikoprofile (PINTA-DIARI). Lübeck: Kompaktbericht an das Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2013).

7. Wölfling K, Thalemann R, Grüsser-Sinopoli SM. [Computer game addiction: a psychopathological symptom complex in adolescence]. Psychiatr Praxis. (2008) 35:226–32. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-986238

8. Stevens MW, Dorstyn D, Delfabbro PH, King DL. Global prevalence of gaming disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2021) 55:553–68. doi: 10.1177/0004867420962851

9. Greenfield DN. Psychological characteristics of compulsive Internet use: a preliminary analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav. (1999) 2:403–12. doi: 10.1089/cpb.1999.2.403

10. Young K. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychol Behav. (1998) 1:237–44. doi: 10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237

11. Carli V, Durkee T, Wasserman D, Hadlaczky G, Despalins R, Kramarz E, et al. The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: a systematic review. Psychopathology. (2013) 46:1–13. doi: 10.1159/000337971

12. Andreassen CS, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. (2016) 30:252. doi: 10.1037/adb0000160

13. Bielefeld M, Drews M, Putzig I, Bottel L, Steinbüchel T, Dieris-Hirche J, et al. Comorbidity of Internet use disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: two adult case-control studies. J Behav Addict. (2017) 6:490–504. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.073

14. Steinbüchel TA, Herpertz S, Dieris-Hirche J, Kehyayan A, Külpmann I, Diers M, et al. [internet addiction and suicidality – a comparison of internet-dependent and non-dependent patients with healthy controls]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. (2020) 70:457–66. doi: 10.1055/a-1129-7246

15. Dieris-Hirche J, Bottel L, Bielefeld M, Steinbüchel T, Kehyayan A, Dieris B, et al. Media use and internet addiction in adult depression: a case-control study. Comput Hum Behav. (2017) 68:96–103.

16. González-Bueso V, Santamaría JJ, Fernández D, Merino L, Montero E, Ribas J. Association between internet gaming disorder or pathological video-game use and comorbid psychopathology: a comprehensive review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:668. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040668

17. Lopez-Fernandez O, Williams AJ, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ. Female gaming, gaming addiction, and the role of women within gaming culture: a narrative literature review. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:454. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00454

18. Laconi S, Pirès S, Chabrol H. Internet gaming disorder, motives, game genres and psychopathology. Comput Hum Behav. (2017) 75:652–9.

19. Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Internet Addiction Treatment: The Therapists’ View. Internet Addiction in Psychotherapy. Berlin: Springer (2015). p. 6–14.

20. Griffiths M, Lewis A. Confronting gender representation: a qualitative study of the experiences and motivations of female casual-gamers. Aloma: Revista de Psicologia, Ciències de l’Educació i de l’Esport. (2011) 28:245–72.

21. Xu DD, Lok KI, Liu HZ, Cao XL, An FR, Hall BJ, et al. Internet addiction among adolescents in Macau and Mainland China: prevalence, demographics and quality of life. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:16222. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73023-1

22. Fatehi F, Monajemi A, Sadeghi A, Mojtahedzadeh R, Mirzazadeh A. Quality of life in medical students with internet addiction. Acta Med Iran. (2016) 54:662–6.

23. Gao T, Xiang YT, Qin Z, Hu Y, Mei S. Internet addiction and quality of life in college students: a multiple mediation analysis. Iran J Public Health. (2019) 48:2094–6.

24. Lu L, Xu DD, Liu HZ, Zhang L, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, et al. Internet addiction in Tibetan and Han Chinese middle school students: prevalence, demographics and quality of life. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 268:131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.005

25. Wartberg L, Kriston L, Kammerl R. Associations of social support, friends only known through the internet, and health-related quality of life with internet gaming disorder in adolescence. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2017) 20:436–41. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0535

26. Lim JA, Lee JY, Jung HY, Sohn BK, Choi SW, Kim YJ, et al. Changes of quality of life and cognitive function in individuals with Internet gaming disorder: a 6-month follow-up. Medicine (Baltimore). (2016) 95:e5695. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005695

27. Marchica LA, Mills DJ, Keough MT, Derevensky JL. Exploring differences among video gamers with and without depression: contrasting emotion regulation and mindfulness. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23:119–25. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0451

28. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. (1998) 59(Suppl. 20):22–33; quiz 4–57.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Section III – Conditions for Further Study. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

30. Pawlikowski M, Altstötter-Gleich C, Brand M. Validation and psychometric properties of a short version of Young’s internet addiction test. Comput Hum Behav. (2013) 29:1212–23.

31. Whoqol-Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. (1998) 28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667

32. Angermeyer M, Kilian R, Matschinger H. WHOQOL-100 und WHO-QOL-BREF. Handbuch für die Deutschsprachige Version Der who Instrumente Zur Erfassung von Lebensqualität Göttingen Bern Toronto. Seattle, WA: Hogrefe (2000).

33. Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. (2004) 13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00

35. Hautzinger M, Keller F, Kühner C. Beck Depressions-Inventar (BDI-II). New York, NY: Harcourt Test Services (2006).

36. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1988) 56:893–7. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.56.6.893

37. Derogatis LR. BSI Brief Symptom Inventory. Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems (1993).

38. Kliem S, Brähler E. Brief Symptom Inventory BSI von L.R. Derogatis: Deutsche Fassung [Brief Symptom Inventory BSI (BSI): German Version]. New York, NY: Pearson Assessment & Information (2017).

39. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. (2007) 39:175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146

40. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc (1988). p. 13.

41. Karimy M, Parvizi F, Rouhani MR, Griffiths MD, Armoon B, Fattah Moghaddam L. The association between internet addiction, sleep quality, and health-related quality of life among Iranian medical students. J Addict Dis. (2020) 38:317–25. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2020.1762826

42. Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, Lemmens JS, Rumpf HJ, Mößle T, et al. An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction. (2014) 109:1399–406. doi: 10.1111/add.12457

43. Griffiths MD, van Rooij AJ, Kardefelt-Winther D, Starcevic V, Király O, Pallesen S, et al. Working towards an international consensus on criteria for assessing internet gaming disorder: a critical commentary on Petry et al (2014). Addiction. (2016) 111:167–75. doi: 10.1111/add.13057

44. Billieux J, King DL, Higuchi S, Achab S, Bowden-Jones H, Hao W, et al. Functional impairment matters in the screening and diagnosis of gaming disorder: commentary on: scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 gaming disorder proposal (Aarseth et al). J Behav Addict. (2017) 6:285–9. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.088

45. Aarseth E, Bean AM, Boonen H, Colder Carras M, Coulson M, Das D, et al. Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 gaming disorder proposal. J Behav Addict. (2017) 6:267–70. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.088

46. Lau JTF, Walden DL, Wu AMS, Cheng KM, Lau MCM, Mo PKH. Bidirectional predictions between Internet addiction and probable depression among Chinese adolescents. J Behav Addict. (2018) 7:633–43. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.87

47. Henchoz Y, Studer J, Deline S, N’Goran AA, Baggio S, Gmel G. Video gaming disorder and sport and exercise in emerging adulthood: a longitudinal study. Behav Med. (2016) 42:105–11. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2014.965127

48. Liu Q, Li X. The interactions of media use, obesity, and suboptimal health status: a nationwide time-trend study in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:13214. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413214

49. Robinson TN, Banda JA, Hale L, Lu AS, Fleming-Milici F, Calvert SL, et al. Screen media exposure and obesity in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. (2017) 140(Suppl. 2):S97–101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758K

50. Paschke K, Austermann MI, Thomasius R. Assessing ICD-11 gaming disorder in adolescent gamers by parental ratings: development and validation of the gaming disorder scale for parents (GADIS-P). J Behav Addict. (2021) 10:159–68. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00105

51. Paschke K, Austermann MI, Thomasius R. Assessing ICD-11 gaming disorder in adolescent gamers: development and validation of the gaming disorder scale for adolescents (GADIS-A). J Clin Med. (2020) 9:993. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040993

52. Przepiorka AM, Blachnio A, Miziak B, Czuczwar SJ. Clinical approaches to treatment of Internet addiction. Pharmacol Rep. (2014) 66:187–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2013.10.001

53. Zajac K, Ginley MK, Chang R. Treatments of internet gaming disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. Expert Rev Neurother. (2020) 20:85–93. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2020.1671824

54. Wölfling K, Müller KW, Dreier M, Ruckes C, Deuster O, Batra A, et al. Efficacy of short-term treatment of internet and computer game addiction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2019) 76:1018–25. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1676

Keywords: internet use disorder, internet addiction, gaming disorder, quality of life, comorbid, dual diagnosis, behavioral addiction

Citation: Dieris-Hirche J, te Wildt BT, Pape M, Bottel L, Steinbüchel T, Kessler H and Herpertz S (2022) Quality of Life in Internet Use Disorder Patients With and Without Comorbid Mental Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 13:862208. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.862208

Received: 25 January 2022; Accepted: 22 February 2022;

Published: 24 March 2022.

Edited by:

Carlos Roncero, University of Salamanca, SpainReviewed by:

Gallus Bischof, University of Lübeck, GermanyCopyright © 2022 Dieris-Hirche, te Wildt, Pape, Bottel, Steinbüchel, Kessler and Herpertz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jan Dieris-Hirche, amFuLmRpZXJpcy1oaXJjaGVAcnViLmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.