- Institute of Health and Wellbeing, College of Medical Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

Negative symptoms have attracted growing attention as a psychological treatment target and the past 10 years has seen an expansion of mechanistic studies and clinical trials aimed at improving treatment options for this frequently neglected sub-group of people diagnosed with schizophrenia. The recent publication of several randomized controlled trials of psychological treatments that pre-specified negative symptoms as a primary outcome warrants a carefully targeted review and analysis, not least because these treatments have generally returned disappointing therapeutic benefits. This mini-review dissects these trials and offers an account of why we continue to have significant gaps in our understanding of how to support recovery in people troubled by persistent negative symptoms. Possible explanations for mixed trial results include a failure to separate the negative symptom phenotype into the clinically relevant sub-types that will respond to mechanistically targeted treatments. For example, the distinction between experiential and expressive deficits as separate components of the wider negative symptom construct points to potentially different treatment needs and techniques. The 10 negative symptom-focused RCTs chosen for analysis in this mini-review present over 16 different categories of treatment techniques spanning a range of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, interpersonal, and metacognitive domains of functioning. The argument is made that treatment development will advance more rapidly with the use of more precisely targeted psychological treatments that match interventions to a focused range of negative symptom maintenance processes.

Introduction

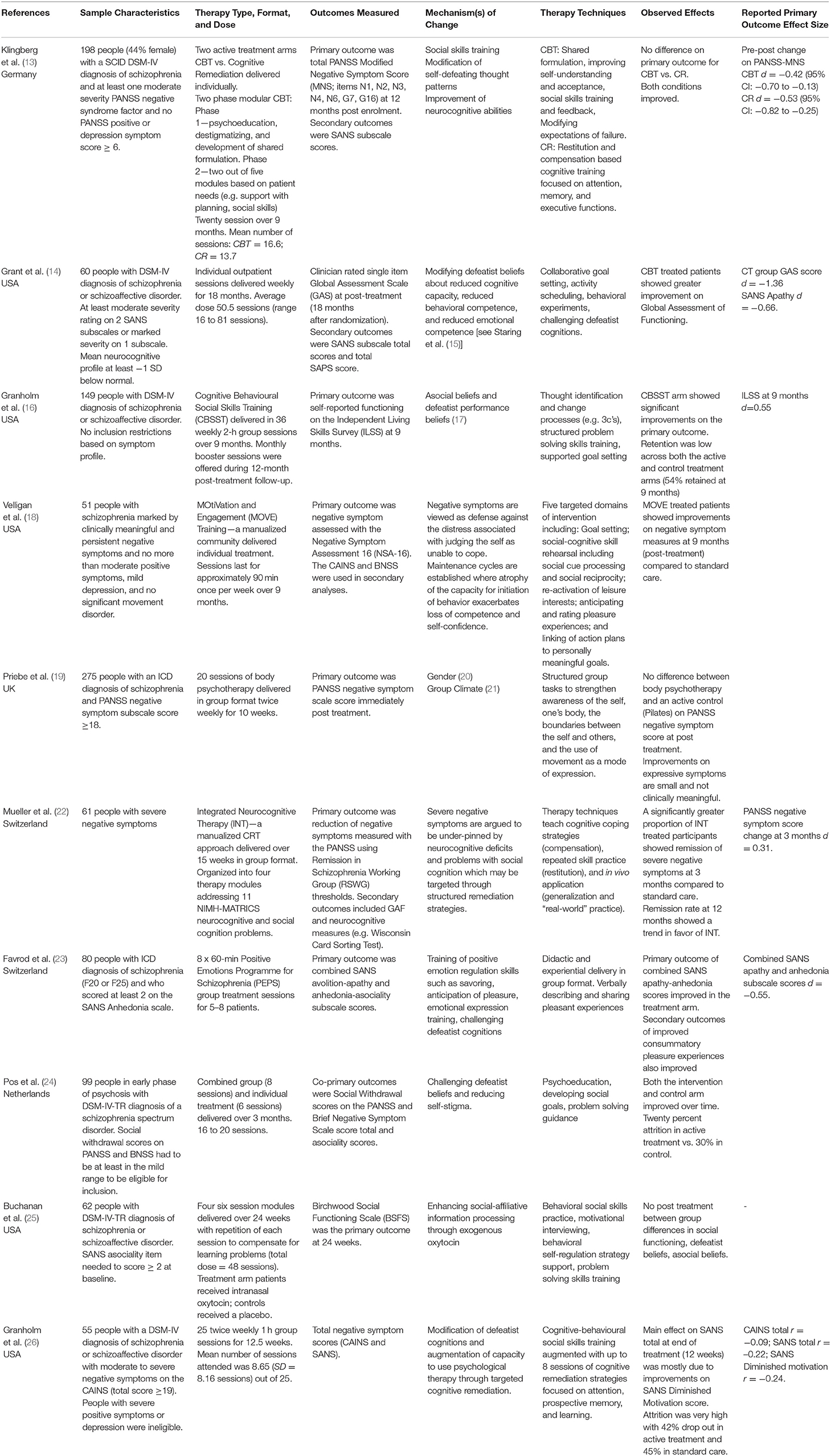

Providing psychological therapies for paranoia and distressing hallucinations alongside pharmacotherapy and other medical treatments is now well-established in clinical guidelines (1) and there continues to be considerable innovation in the types of therapies being developed for positive symptoms [e.g. (2, 3)]. However, the negative symptoms of schizophrenia such as avolition-apathy and diminished expressive abilities have remained a major source of distress and arrested recovery that frequently present a significant treatment challenge (4, 5). Furthermore, surveys of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia suggest that loss of emotional engagement and low motivational drive are a high priority for treatment (6) but at present there are very few effective psychological or pharmacological treatment options (7–9). This lack of progress in the development of viable treatments is particularly frustrating as earlier meta-analytic evidence suggested that even general CBTp led to medium effect size reductions on negative symptoms [d = 0.437, 95% CI: 0.171–0.704; (10)]. Also, it has become clearer that negative symptoms fluctuate more than previously assumed (11), leading to renewed hope that psychological interventions could be deployed to accelerate recovery. Reasons for cautious optimism can be drawn from recent meta-analytic evidence that suggests psychological treatments for negative symptoms can be beneficial, although the effects are less substantial when trial quality is factored in (12). To help accelerate the refinement of viable treatment packages this mini-review set out to analyze a range of negative symptom treatment trials conducted in the past decade with the aim of identifying ways that the targeting of treatments could be improved in future studies. Psychological treatment RCTs with the pre-specified aim of evaluating effects on negative symptoms were selected for review and analysis. The eligible papers were closely scrutinized, descriptive information was extracted, and themes and patterns across the studies were explored. Table 1 presents the key summary information from each paper with the emphasis placed on describing which negative symptoms were targeted, what therapeutic techniques were applied, the proposed mechanisms of therapeutic change, and the effects observed including acceptability and implementation outcomes such as attrition. Where the authors presented effect sizes these are reported to support description and comparison across studies.

Table 1. A descriptive summary of selected psychological treatment RCTs with negative symptoms specified as a primary or co-primary outcome 2009–2021.

One Problem or Many? Subdividing the Negative Symptom Clinical Phenotype

One feature of this set of studies is that there is considerable heterogeneity in the clinical profile of people recruited into the trials and just about every study specifies a different constellation of primary and co-primary outcomes. This is an important issue as it is recognized that negative symptoms are more helpfully understood as comprising at least two separable sub-factors (27, 28) and that a very similar clinical phenotype can be seen when withdrawal and isolative behaviors are secondary to different underlying mechanisms such as positive symptoms or medication side effects (4, 29). Although nine of the included studies set some threshold for negative symptom severity as part of trial eligibility, only three clearly specified patient exclusion criteria based on the co-presence of positive symptoms or depressive features. These variations in method also extend to the ways that the primary outcomes were measured with seven studies using established negative symptom scales (e.g. CAINS, PANSS, SANS, BNSS) and the remaining three studies using measures of global functioning, social functioning, or independent living skills. There were also variations in practice across studies using established negative symptom measures as the outcome with some using a composite score of all negative symptoms and others selecting relevant subscale scores that indexed the negative symptom domain of interest [e.g. Favrod et al. (23) combined SANS avolition-apathy and anhedonia-asociality subscale scores as their primary outcome of the PEPS intervention programme]. As a result, the selected set of papers do not describe findings for a clearly delineated group of people with negative symptoms.

What Works, On What and for Whom?

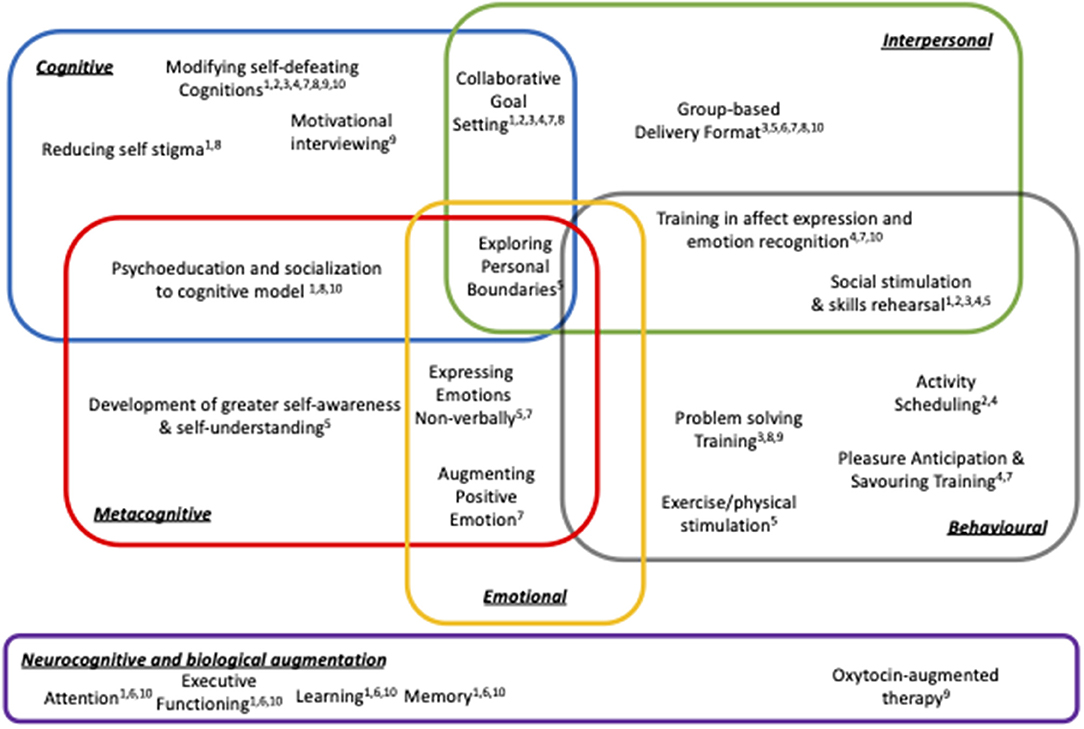

Six of the 10 studies returned results suggestive of at least some impact of the tested therapies on the targeted primary outcomes and the effect sizes reported are of a similar magnitude to those presented in previous meta-analyses (10). However, in several instances both the intervention and control arm patients showed improvements, possibly suggesting that for some people with negative symptoms giving any kind of supportive contact may be beneficial (30). The past 10 years has also seen a substantial increase in the studies testing one of the main tenets of the cognitive model of negative symptoms (31)—that self-defeating cognitions are a key cause and maintenance factor (32, 33). As described in Table 1 and depicted in Figure 1, helping people with negative symptoms to identify, challenge, and modify self-defeating beliefs is explicitly mentioned in eight of the 10 studies analyzed here. This is by far the most common strategy deployed across the studies. As highlighted in the mechanisms of change column of Table 1, two studies have supplementary analyses which suggest that modification of defeatist cognitions at least partially mediate treatment outcomes (15). The analysis of treatment mediators across other studies suggests that factors such as patient gender (20) and group climate (21) may also influence some treatment effects.

Figure 1. Schematic summary of treatment strategies across negative symptom focused RCTs (superscript numbers refer to papers listed in Table 1).

However, one of the key observations of this review is that understanding the mechanisms of change and the doses of therapy needed to produce beneficial effects is obscured by the extensive array of techniques, procedures, and therapy combinations that have been deployed to support people struggling to recover from negative symptoms. Figure 1 portrays this information in schematic form and shows that while the treatment protocols tested to date may share some features (e.g. attention to reducing defeatist cognitions), heterogeneity of treatment packages is the norm. It should be noted that the constellation of treatment techniques and the domains of therapeutic action depicted in Figure 1 does not fully capture all of the nuances and complex processes involved in the negative symptom therapy packages described. But, it does provide a framework for deconstructing and analyzing the psychological treatment methods that have been used to support people with negative symptoms. Splitting treatment packages into constituent parts provides one way of identifying testable hypotheses about plausible mechanisms of therapeutic change that can be then used to refine future therapy protocols.

Splitting Things Apart

To advance our understanding of promising psychological treatment strategies for negative symptoms the therapeutic procedures described in each of the trials was “split apart” into constituent techniques. In some trials there was a clear link between the therapy techniques and the underlying theory of symptom formation and/or maintenance. For example, eliciting and challenging defeatist cognitions is a core feature of the dominant CBT model of negative symptoms and this leads to use of strategies such as belief modification and associated behavioral experiments. But, in other trials the link between the techniques and mechanisms of change were more opaque, or there were compound techniques that involved a mixture of potential change processes. Figure 1 depicts five overlapping categories of intervention that addressed cognitive, interpersonal, emotional, behavioral, and metacognitive domains. These are underpinned by a sixth neurocognitive/biological domain which has been introduced in a number of trials to convey how neural factors may provide a substrate that can constrain the potential for recovery (34, 35). By mapping the variety of therapy techniques reported across studies to this framework we can also see that some therapeutic strategies will require the operation of overlapping systems. For example, successfully exploring personal boundaries described in Body Oriented Psychotherapy may involve successful coordination of metacognitive, interpersonal, emotional and behavioral systems and a breakdown in any one domain may make it difficult for a person to fully capitalize on therapy. Other therapeutic strategies may be simpler to implement because they make less complex demands on the patient and can be structured and scaffolded by a therapist (e.g. activity scheduling). Hence, Figure 1 summarizes the candidate processes involved in supporting recovery from negative symptoms and tries to capture some of the reasons why the understanding of psychological treatment for negative symptoms is still very much a work in progress.

This approach to refining negative symptom treatments is warranted given the evidence that psychological treatments for positive psychotic symptoms have advanced through the use of causal manipulationist techniques that specify and modify psychological processes causally related to the clinical phenomenon of interest (2, 36). Currently the negative symptom treatment literature is dominated by multicomponent treatments, some elements of which are offshoots of experimental studies, but the specification of mechanistic targets is often incomplete. Next generation psychological treatment studies for negative symptoms are likely to benefit from a more explicit bottom-up development approach (37).

Putting Things Back Together Again

A symptom rather than syndrome focus has been highly successful for psychological treatment research over the past 30 years (38) and in psychosis treatment studies the focus on specific symptoms has driven several therapy refinements (39). In some notable instances, treatment trials focused on discrete symptoms such as command hallucinations have produced some of the largest treatment effect sizes in the literature (40). When considering which negative symptoms to focus on in future treatment development, the current evidence suggests that at least the experiential and expressive subdomains should be treated as different types of problems in need of suitably tailored treatment approaches (41). The therapeutic value of more precisely matching treatments strategies to problem subtypes is beginning to be shown by meta-analytic results which suggest that CBT may be more effective for amotivation while cognitive remediation approaches may address problems of diminished expression (12). Future success in improving treatments will also be helped by following consensus guidelines that support the assessment and appropriate sub-classification of persistent, predominant, prominent, primary, and secondary negative symptoms (42). However, in taking specific symptom focused approach it is also important that future negative symptom treatment development does not lose sight of the whole person receiving care. In addition to “splitting things apart” to target specific symptoms we must also ensure that treatments also use person-centered formulation to help re-construct the fragmented self-experience that underpins schizophrenia (43). As highlighted in Figure 1, a number of the therapeutic strategies evident in existing treatment protocols are likely to be beneficial because they enrich the persons capacity to understand themselves, the boundary between the self and other people, and the operation of key experiences such as emotional self-regulation and the modulation of social interactions. Supporting these integrative processes is likely to be a necessary component of any successful psychosis intervention (44). This maps to the process of individual case formulation which has been shown to enhance the outcome of CBT for hallucinations (45) and may be particularly relevant to the improvement of interventions for negative symptoms. For example, some people with negative symptoms exhibit such severe disturbances of metacognitive functioning that they may find it extraordinarily difficult to even think about and reflect on their own mental state (46). Matching therapeutic techniques to both the reflective and neurocognitive capacities of the patient provides a way to help people with problematic negative symptoms regain the ability to link their ongoing experiences into the autobiographical narrative needed to support effective social and interpersonal functioning (47, 48). An important challenge for the next phase of negative symptom treatment development will be to convert the increasingly refined set of models used to understand specific negative symptoms into targeted and personalized therapies.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Killaspy H, Baird G, Bromham N, Bennett A, Guideline Committee. Rehabilitation for adults with complex psychosis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. (2021) 372:n1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1

2. Freeman D, Emsley R, Diamond R, Collett N, Bold E, Chadwick E, et al. Comparison of a theoretically driven cognitive therapy (the Feeling Safe Programme) with befriending for the treatment of persistent persecutory delusions: a parallel, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. (2021) 8:696–707. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00158-9

3. Garety P, Edwards CJ, Ward T, Emsley R, Huckvale M, McCrone P, et al. Optimising AVATAR therapy for people who hear distressing voices: study protocol for the AVATAR2 multi-centre randomised controlled trial. Trials. (2021) 22:366. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05301-w

4. Galderisi S, Mucci A, Buchanan RW, Arango C. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new developments and unanswered research questions. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:664–77. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30050-6

5. Aleman A, Lincoln TM, Bruggeman R, Melle I, Arends J, Arango C, et al. Treatment of negative symptoms: where do we stand, and where do we go? Schizophr Res. (2016) 186:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.015

6. Sterk B, Winter RI, Muis M, Haan L de. Priorities, satisfaction and treatment goals in psychosis patients: an online consumer's survey. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2013) 46:88–93. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327732

7. Fusar-Poli P, Papanastasiou E, Stahl D, Rocchetti M, Carpenter W, Shergill S, et al. Treatments of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of 168 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. (2015) 41:892–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu170

8. Velthorst E, Koeter M, Gaag M van der, Nieman DH, Fett AKJ, Smit F, et al. Adapted cognitive–behavioural therapy required for targeting negative symptoms in schizophrenia: meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychol Med. (2014) 45:453–65. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001147

9. Lutgens D, Gariepy G, Malla A. Psychological and psychosocial interventions for negative symptoms in psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatr. (2017) 210:324–32. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.197103

10. Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophr Bull. (2008) 34:523–37. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm114

11. Savill M, Banks C, Khanom H, Priebe S. Do negative symptoms of schizophrenia change over time? A meta-analysis of longitudinal data. Psychol Med. (2014) 45:1613–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002712

12. Riehle M, Böhl MC, Pillny M, Lincoln TM. Efficacy of psychological treatments for patients with schizophrenia and relevant negative symptoms: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Eur. (2020) 2:1–23. doi: 10.32872/cpe.v2i3.2899

13. Klingberg S, Wittorf A, Herrlich J, Wiedemann G, Meisner C, Buchkremer G, et al. Cognitive behavioural treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients: study design of the TONES study, feasibility and safety of treatment. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2009) 259:149–54. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0047-8

14. Grant PM, Huh GA, Perivoliotis D, Stolar NM, Beck AT. Randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of cognitive therapy for low-functioning patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2012) 69:121. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.129

15. Staring ABP, Huurne M-AB ter, Gaag M van der. Cognitive behavioral therapy for negative symptoms (CBT-n) in psychotic disorders: a pilot study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2013) 44:300–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.01.004

16. Granholm E, Holden J, Link PC, McQuaid JR. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for schizophrenia: improvement in functioning and experiential negative symptoms. J Consult Clin Psych. (2014) 82:1173–85. doi: 10.1037/a0037098

17. Granholm E, Holden J, Worley M. Improvement in negative symptoms and functioning in cognitive-behavioral social skills training for schizophrenia: mediation by defeatist performance attitudes and asocial beliefs. Schizophrenia Bull. (2017) 44:653–61. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx099

18. Velligan DI, Roberts D, Mintz J, Maples N, Li X. A randomized pilot study of MOtiVation and Enhancement (MOVE) Training for negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2015) 165:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.04.008

19. Priebe S, Savill M, Wykes T, Bentall RP, Reininghaus U, Lauber C, et al. Effectiveness of group body psychotherapy for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. (2016) 209:54–61. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.171397

20. Savill M, Orfanos S, Bentall R, Reininghaus U, Wykes T, Priebe S. The impact of gender on treatment effectiveness of body psychotherapy for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a secondary analysis of the NESS trial data. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 247:73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.020

21. Orfanos S, Priebe S. Group therapies for schizophrenia: initial group climate predicts changes in negative symptoms. Psychosis. (2017) 9:1–10. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2017.1311360

22. Mueller DR, Khalesi Z, Benzing V, Castiglione CI, Roder V. Does Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy (INT) reduce severe negative symptoms in schizophrenia outpatients? Schizophr Res. (2017) 188:92–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.037

23. Favrod J, Nguyen A, Chaix J, Pellet J, Frobert L, Fankhauser C, et al. Improving pleasure and motivation in schizophrenia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Psychother Psychosom. (2019) 88:84–95. doi: 10.1159/000496479

24. Pos K, Franke N, Smit F, Wijnen BFM, Staring ABP, Gaag MV der, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for social activation in recent-onset psychosis: randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psych. (2019) 87:151–60. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000362

25. Buchanan RW, Kelly DL, Strauss GP, Gold JM, Weiner E, Zaranski J, et al. Combined oxytocin and cognitive behavioral social skills training for social function in people with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharm. (2021) 41:236–43. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001397

26. Granholm E, Twamley EW, Mahmood Z, Keller AV, Lykins HC, Parrish EM, et al. Integrated cognitive-behavioral social skills training and compensatory cognitive training for negative symptoms of psychosis: effects in a pilot randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Bull. (2021) 48:359–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbab126

27. Marder SR, Kirkpatrick B. Defining and measuring negative symptoms of schizophrenia in clinical trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2014) 24:737–43. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.10.016

28. Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. (2006) 32:214–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj053

29. Farreny A, Savill M, Priebe S. Correspondence between negative symptoms and potential sources of secondary negative symptoms over time. Eur Arch Psy Clin N. (2018) 268:603–9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-017-0813-y

30. Radhakrishnan R, Kiluk BD, Tsai J. A meta-analytic review of non-specific effects in randomized controlled trials of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. (2015) 87:57–62. doi: 10.1007/s11126-015-9362-6

31. Rector NA, Beck AT, Stolar N. The negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a cognitive perspective. Can J Psychiatr. (2005) 50:247–57. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000503

32. Luther L, Coffin GM, Firmin RL, Bonfils KA, Minor KS, Salyers MP, et al. test of the cognitive model of negative symptoms: associations between defeatist performance beliefs, self-efficacy beliefs, and negative symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 269:278–85. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.016

33. Campellone TR, Sanchez AH, Kring AM. Defeatist performance beliefs, negative symptoms, and functional outcome in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull. (2016) 42:1343–52. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw026

34. Kring AM, Barch DM. The motivation and pleasure dimension of negative symptoms: Neural substrates and behavioral outputs. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2014) 24:725–36. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.06.007

35. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, Clarke M, Mørch-Johnsen L, Faerden A. Individual negative symptoms and domains – relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment. Schizophr Res. (2016) 186:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013

36. Brand RM, Rossell SL, Bendall S, Thomas N. Can we use an interventionist-causal paradigm to untangle the relationship between trauma, PTSD and psychosis? Front Psychol. (2017) 8:306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00306

37. Cristea IA, Vecchi T, Cuijpers P. Top-down and bottom-up pathways to developing psychological interventions. Jama Psychiat. (2021) 78:593–4. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4793

38. Costello CG. Research on symptoms versus research on syndromes. Arguments in favour of allocating more research time to the study of symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. (1992) 160:304–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.3.304

39. Lincoln TM, Peters E. A systematic review and discussion of symptom specific cognitive behavioural approaches to delusions and hallucinations. Schizophr Res. (2019) 203:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.12.014

40. Birchwood M, Michail M, Meaden A, Tarrier N, Lewis S, Wykes T, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy to prevent harmful compliance with command hallucinations (COMMAND): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. (2014) 1:23–33. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70247-0

41. Strauss GP, Horan WP, Kirkpatrick B, Fischer BA, Keller WR, Miski P, et al. Deconstructing negative symptoms of schizophrenia: avolition-apathy and diminished expression clusters predict clinical presentation and functional outcome. J Psychiatr Res. (2013) 47:783–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.01.015

42. Galderisi S, Mucci A, Dollfus S, Nordentoft M, Falkai P, Kaiser S, et al. EPA guidance on assessment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiat. (2021) 64:e23. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.11

43. Lysaker PH, Minor KS, Lysaker JT, Hasson-Ohayon I, Bonfils K, Hochheiser J, et al. Metacognitive function and fragmentation in schizophrenia: relationship to cognition, self-experience and developing treatments. Schizophr Res Cogn. (2020) 19:100142. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2019.100142

44. Leonhardt BL, Huling K, Hamm JA, Roe D, Hasson-Ohayon I, McLeod HJ, et al. Recovery and serious mental illness: a review of current clinical and research paradigms and future directions. Expert Rev Neurother. (2017) 17:1117–30. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2017.1378099

45. Turner DT, Burger S, Smit F, Valmaggia LR, Gaag M van der. What constitutes sufficient evidence for case formulation–driven CBT for psychosis? Cumulative meta-analysis of the effect on hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Bull. (2020) 46:1072–85. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa045

46. McLeod HJ, Gumley AI, MacBeth A, Schwannauer M, Lysaker PH. Metacognitive functioning predicts positive and negative symptoms over 12 months in first episode psychosis. J Psychiatr Res. (2014) 54:109–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.018

47. Berna F, Potheegadoo J, Aouadi I, Ricarte JJ, Allé MC, Coutelle R, et al. Meta-analysis of autobiographical memory studies in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Schizophr Bull. (2015) 42:56–66. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv099

Keywords: negative symptoms, motivation, apathy, psychological treatment, recovery

Citation: McLeod HJ (2022) Splitting Things Apart to Put Them Back Together Again: A Targeted Review and Analysis of Psychological Therapy RCTs Addressing Recovery From Negative Symptoms. Front. Psychiatry 13:826692. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.826692

Received: 01 December 2021; Accepted: 28 March 2022;

Published: 12 May 2022.

Edited by:

Armida Mucci, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyReviewed by:

Stefano Barlati, University of Brescia, ItalyMarcel Riehle, University of Hamburg, Germany

Copyright © 2022 McLeod. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hamish J. McLeod, aGFtaXNoLm1jbGVvZEBnbGFzZ293LmFjLnVr

Hamish J. McLeod

Hamish J. McLeod