- 1Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 2A. J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 3Department of Community Health and Prevention, School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 4School of Medicine, University of Colorado, Aurora, CO, United States

Background: Coping can moderate the relationship between trauma exposure and trauma symptoms. There are many conceptualisations of coping in the general population, but limited research has considered how autistic individuals cope, despite their above-average rates of traumatic exposure.

Objectives: To describe the range of coping strategies autistic individuals use following traumatic events.

Methods: Fourteen autistic adults and 15 caregivers of autistic individuals, recruited via stratified purposive sampling, completed semi-structured interviews. Participants were asked to describe how they/their child attempted to cope with events they perceived as traumatic. Using an existing theoretical framework and reflexive thematic analysis, coping strategies were identified, described, and organized into themes.

Results: Coping strategies used by autistic individuals could be organized into 3 main themes: (1) Engaging with Trauma, (2) Disengaging from Trauma, and (3) Self-Regulatory Coping. After the three main themes were developed, a fourth integrative theme, Diagnostic Overshadowing, was created to capture participants' reports of the overlap or confusion between coping and autism-related behaviors.

Conclusions: Autistic individuals use many strategies to cope with trauma, many of which are traditionally recognized as coping, but some of which may be less easily recognized given their overlap with autism-related behaviors. Findings highlight considerations for conceptualizing coping in autism, including factors influencing how individuals cope with trauma, and how aspects of autism may shape or overlap with coping behavior. Research building on these findings may inform a more nuanced understanding of how autistic people respond to adversity, and how to support coping strategies that promote recovery from trauma.

Introduction

Psychological trauma can be defined as events or circumstances that are experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening, and that are associated with lasting adverse effects on functioning and well-being substance abuse and mental health services administration (SAMHSA) (1). This broad definition underscores that what is traumatic varies from one person to another. Moreover, trauma results not only from an event or circumstance itself, but also from the way one appraises and copes with that event or circumstance. Traumatic reactions are similarly variable, encompassing a wide range of emotional and behavioral outcomes including but not limited to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – a specific set of stress, intrusion, avoidance, mood, or arousal symptoms that persist for over a month after the traumatic event (2). Research suggests behavioral responses to trauma (e.g., avoidance, hyperarousal), relative to internalized symptoms (e.g., a sense of a foreshortened future or self-blame), are more common or at least more observable in young children and individuals with significant developmental delays (3, 4). These developmental differences in traumatic responses have prompted the adoption of adjusted assessment approaches and PTSD criteria for these groups (3, 4).

In response to trauma, people attempt to cope. Coping is a broad term encompassing cognitive and behavioral strategies that vary across individuals and situations, but share a common purpose “to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (5). Coping has been found to moderate the development of PTSD: for example, coping centered around avoidance or self-blame may strengthen relationships between trauma exposure and traumatic stress, whereas coping focused on positive reappraisal may weaken this link (6, 7). Similarly, avoidant coping strategies have been associated with increased PTSD symptomology (8, 9) and poorer PTSD treatment response (10). Extensive literature on the post-traumatic coping of non-autistic individuals has informed several different coping conceptualizations and measures (11). One widely-cited framework, proposed by Tobin et al. (12), that we used for this study, situates coping strategies along two dimensions – problem vs. emotion focused, and approach vs. avoidance focused. Though avoidance-focused strategies are traditionally viewed as maladaptive, and approach-focused strategies as adaptive (11), this dichotomy has recently been challenged by research demonstrating that the functionality of coping is nuanced and context-dependent (13, 14). For example, avoidance strategies may serve a protective function for children facing urgent and uncontrollable stress; however, overreliance on avoidance outside of these situations prevents children from learning alternative coping skills, and over time, avoidance behaviors may place them at risk for developing mental health difficulties, including PTSD (15, 16).

As with traumatic reactions, it has been suggested that coping behaviors may vary with one's developmental level: although children can and do employ similar strategies to adults, there is a tendency for people to adopt more problem-focused (i.e., directly attempting to alter the source of trauma), and fewer avoidance-based (i.e., attempting to circumvent situations that provoke trauma-related symptoms) strategies as they age (17). Elsewhere, developmental theories of coping posit that the adoption, specificity, and effectiveness of problem-focused coping coincides with neurological development and the emergence of increasingly sophisticated executive functioning abilities, such as cognitive flexibility and fluid reasoning (15, 18). Other research examining how adults with intellectual disability cope with social stress suggests that their coping strategies largely align with those used by the general population (19), but may be focused more on avoiding trauma-associated situations than on gaining control over a situation (19, 20). Further, within active coping, strategies focused on altering the source of trauma appear to be more readily used than those focused on altering one's emotional state (19). In sum, the literature on coping in different populations suggests that individual differences (e.g., developmental level, intellectual ability) play an important role in shaping the coping strategies available to different people.

Autistic individuals experience higher rates of potentially traumatic events [PTE; (21–23)] than the general population. These events have been linked to elevated rates of mental health conditions in autistic youth (24, 25) and PTSD in autistic adults (26). Researchers have proposed transactional relationships in which autistic traits (e.g., social communication differences, patterns of restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests, sensory sensitivities) and behaviors related, but not central to, an autism diagnosis (e.g., emotion dysregulation) influence the experience of trauma at multiple levels – including what stressful events are encountered and experienced as traumatic, and how traumatic reactions develop and manifest (26–29). These ideas are supported by studies suggesting elevated rates of PTE (22, 23, 30–32), PTSD and other traumatic reactions (26, 28, 33, 34) among autistic people.

Coping may be a crucial mechanism linking PTE to traumatic reactions for autistic people. It has been hypothesized that autistic individuals may struggle to cope effectively with PTE, perhaps due to increased social marginalization, and executive functioning and emotion regulation challenges (26, 27, 29). Moreover, researchers have suggested that traumatic reactions may increase autistic traits via coping behaviors, suggesting a complex relationship between these conditions (27, 35). Empirical research in non-trauma contexts suggests that autistic children use more avoidance and venting strategies, and fewer emotion regulation and social support strategies, compared to their non-autistic peers (36, 37). Recently, qualitative research has begun to explore autistic people's experiences of coping in everyday life. Studies have found that autistic adults report a wide range of strategies or experiences that help them cope and build resilience, including strategies commonly reported in the broader coping literature, such as engaging in recreational activities or seeking social support, as well as strategies that may be more autism-specific, such as seeking support from the autistic community, using technology to facilitate social interactions and daily activities, masking, or self-understanding and acceptance following their autism diagnosis; (38, 39). Elsewhere, autistic adolescents and adults have described stimming as an adaptive coping mechanism that helps them self-regulate, self-soothe, and communicate when faced with overwhelming sensory environments, thoughts and emotions, or uncertainty (40, 41). Taken together, an emerging literature suggests that autistic people engage in a variety of coping behaviors, some of which converge with existing categorizations and definitions of coping, and some of which may be specific to autism. However, limited research to date has focused on autistic people's experiences of coping with trauma specifically. Moreover, existing research has focused primarily on autistic adults' first-hand narratives. Parental perspectives may provide valuable information on how autistic children, or those with varied communication abilities, respond to trauma. Although past qualitative studies have shed light on how the parents of autistic individuals cope with stressors (42), research has yet to ask the parents of autistic individuals about their children's coping behaviors.

Research suggests that what constitutes a traumatic event and reaction varies across autistic and non-autistic individuals (27, 29, 43–45). In the same way, coping may also vary between autistic and non-autistic people. An important step toward understanding how autistic people respond to trauma is to conduct open-ended explorations of diverse personal narratives. This may help generate accurate frameworks for future research and practice. Therefore, in this study we used qualitative methods to explore firsthand and caregiver perspectives on how autistic people cope with trauma, with the aim of describing the range of coping strategies used by autistic individuals.

Methods

Participants

Participants took part in a broader study of the sources, nature, and experiences of trauma among autistic people (46). The current study is a secondary analysis of the data collected in this original study. In total, fourteen autistic adults and 15 caregivers of autistic individuals (hereafter collectively referred to as “participants”) were recruited via US-based autism-related organizations, the researchers' professional networks, or word of mouth. Using stratified purposive sampling, participants of varied genders, ages, clinical presentations, and adversity histories were included to ensure a diverse range of perspectives. Participants were required to be 18–70 years old and fluent in English. Caregivers (biological or adoptive parents) were selected to ensure representation of individuals unable to participate themselves (i.e., very young children or individuals with significant communication challenges). Three parent-child dyads were included in the final sample. Upon enrolling in the study, participants completed a study-specific survey of socio-demographics, diagnostic history, and for parents, their child's communication ability. Participants also completed measures of PTE [Trauma History Questionnaire [THQ; (47, 48)]] and, for autistic adults, a self-report of post-traumatic symptoms [PTSD Diagnostic Scale for adults [PDS-5; (49)]].

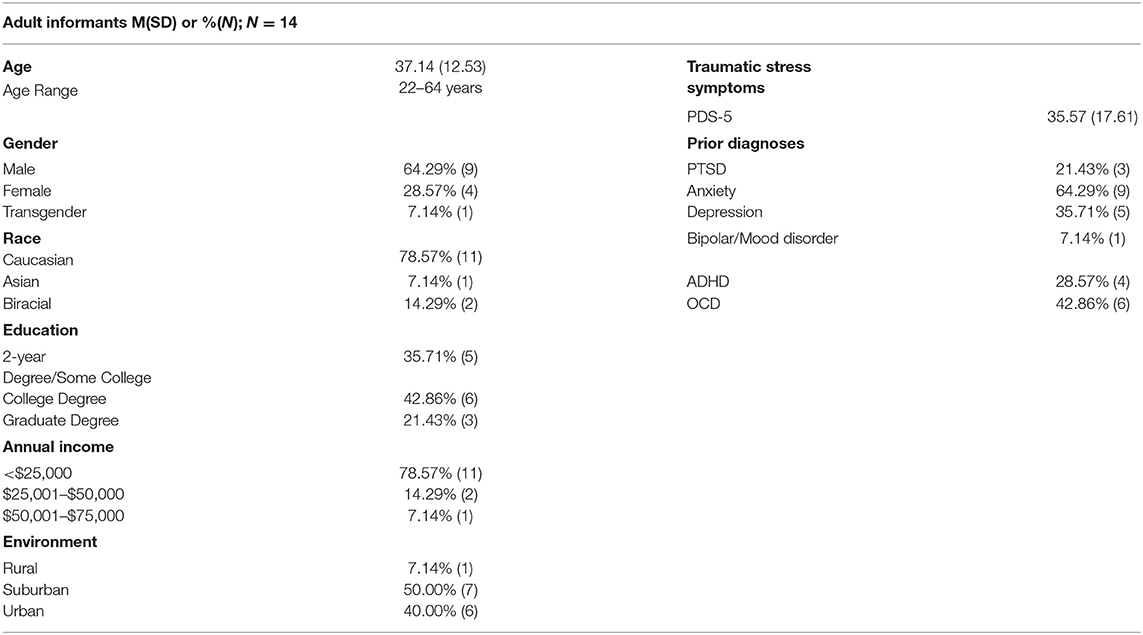

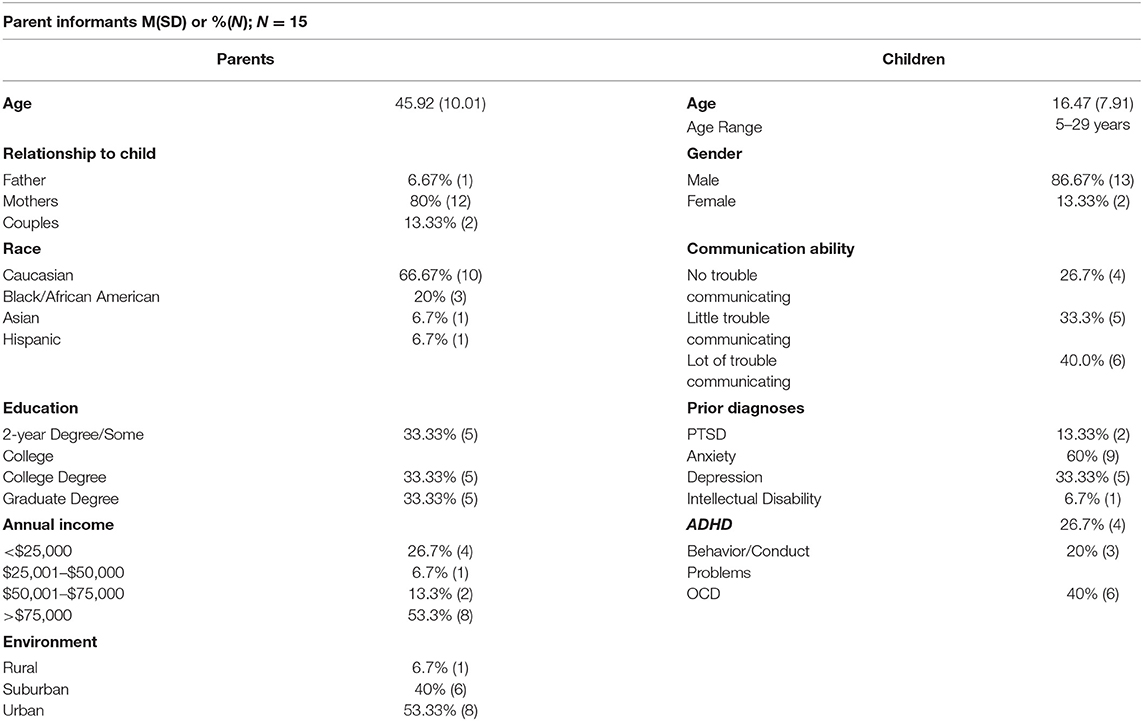

Autistic adult informants (Table 1) were predominantly Caucasian (n = 11; 79%) and male (n = 9; 64%). The majority (n = 11; 79%) had an annual income of < $25,000. All 14 were verbally fluent. Caregiver informants (Table 2) were predominantly mothers (n = 12; 93%), and more racially and socioeconomically diverse. The majority of caregiver informants' children were male (n = 13; 87%) and had some degree of difficulty communicating (n = 11; 73%). Details of psychiatric comorbidities (per self-reported community diagnoses) in the sample are provided in Tables 1, 2. Anxiety, depression and OCD were the most common comorbidities. Community diagnoses of PTSD were reported by three (21%) individuals in the autistic adult sample and two (13%) caregivers, both of adult children. Among the autistic adult participants, 10 (71%) scored above the clinical cut-off on the PDS. These results are consistent with prior work suggesting that PTSD is often undetected and undiagnosed in autistic people (26); however, the research examining the accuracy of the PDS in autistic samples is also needed.

Autistic adults and the children of participating caregivers needed to have (a) received a community diagnosis of autism and (b) experienced a self-reported traumatic event that negatively impacted their well-being for >1 month (per self/parent report), a time-criterion commonly used to differentiate acute from post-traumatic stress (2). Autism status was corroborated by ensuring all participants exceeded clinical cut-offs for autism on either the Ritvo Autism and Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised Screen [RAADS-14; clinical cut-off >13; (50)] for adults, or the Social Communication Questionnaire [SCQ; clinical cut-off >15; (51)] for children. Given studies suggesting that for autistic individuals, traumatic reactions arise from a broad array of experiences and not only those events defined in PTSD criteria (28, 46, 52), trauma sources were not restricted so long as they were associated with prolonged (>1 month) distress. Trauma sources, as reported by participants via the THQ and qualitative interviews, are presented in Supplementary Material 1: physical abuse, emotional abuse, bullying, and “other traumas,” which included varied forms of social exclusion, instances of sensory overload, and traumatic transitions/changes [see (46), for further information].

Interview Procedure

Procedures were approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board. Participants gave informed consent. Data was collected during 60–90 min qualitative interviews, conducted and recorded by CMK – a Caucasian female, clinical psychologist, and researcher with expertise in autism and stress-related disorders. Interviews were completed in-person at the research center (n = 13), over the phone (n = 15), or via email (n = 1) according to participant preference over a 6-month period in 2017. During the interview conducted via email, the interviewer sent all interview questions to the participant in a single document. Responses, once returned via email, were reviewed by the interviewer, who then sent a final round of follow-up questions to clarify meaning as needed.

The interview guide is provided in Supplementary Material 2. The guide was developed with a multidisciplinary (social work, psychology, psychiatry, epidemiology, sociology) team and revised per stakeholder (autistic adults, caregivers) recommendations, to ensure sensitivity and offset researcher positionality. As autistic individuals may experience a wider range of events as traumatic than defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; 2), participants were given the SAMHSA (1) trauma definition (previously outlined in the Introduction) and asked to describe events in their/their child's life they perceived as traumatic. They were also asked to describe coping strategies: all participants were asked, “Were there things you/they did to help yourself/themselves feel better or to get through?” Field notes taken during interviews were shared with participants for clarification and validation [for further protocol details see (46)].

Thematic Analysis

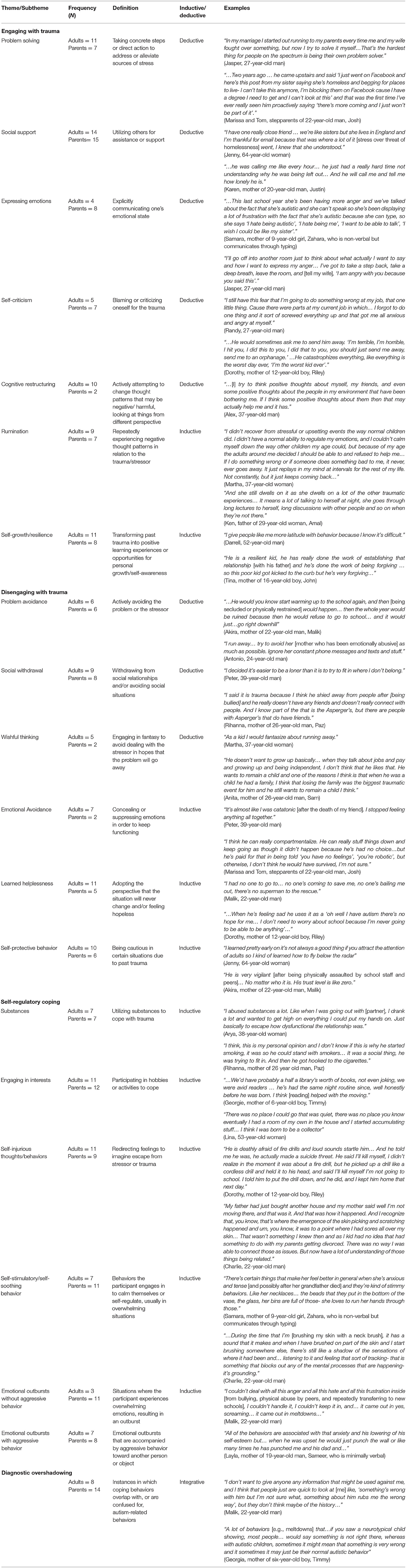

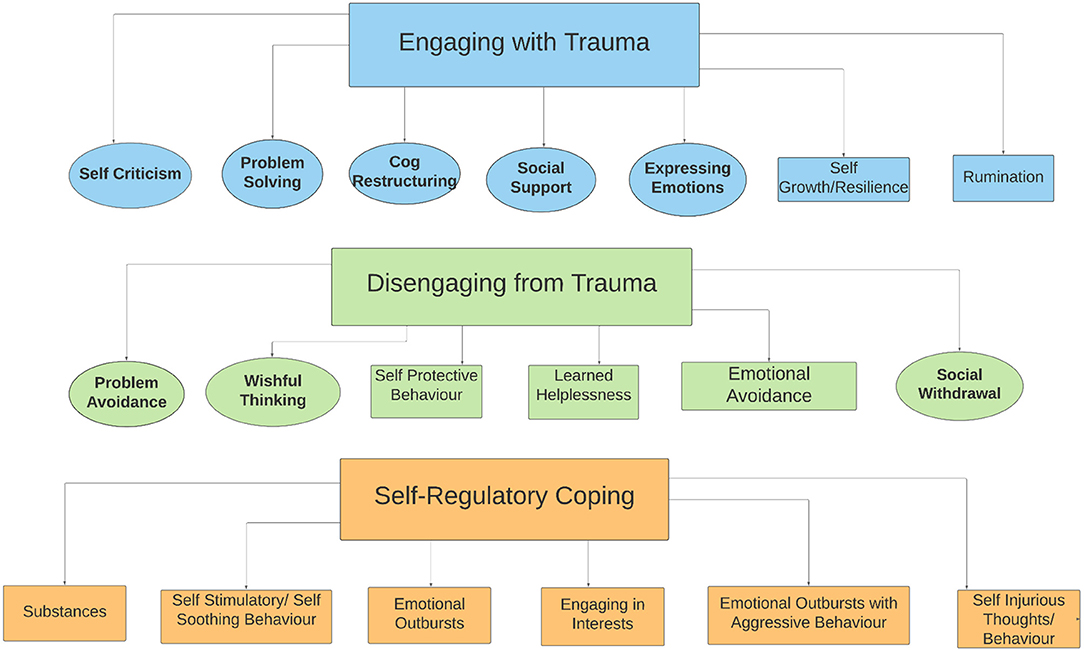

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and submitted to thematic analysis using Nvivo (53). All participants were assigned a pseudonym. Using a realist framework and semantic coding approach, which integrated inductive (a ‘bottom-up' approach whereby themes are generated from data, not pre-existing theory) and deductive (a ‘top-down' approach; driven by prior theory) analyses, themes were identified via six iterative stages: data familiarization, coding, theme generation, review, and definition, and writing (54, 55). This approach allowed the identification of coping strategies already prominent in the existing coping literature (deductive), as well as behaviors less commonly identified as coping, or potentially more specific to autism (inductive). Deductive codes and identification of themes were guided by Tobin et al.'s (12) theoretical framework, but then modified to include inductive codes/themes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Thematic map of coping strategies. Circles represent deductive codes [originating from Tobin et al. (12) framework]; rectangles represent inductive codes [any codes identified in dataset not outlined in the Tobin et al. (12) framework]; green codes indicate the Disengaging from Trauma theme, blue codes the Engaging with Trauma theme, and orange codes the Self-Regulatory theme. This figure was created in Lucidchart.

Two primary analysts (AR and HP) familiarized themselves with four interviews (two adult, two caregiver), and identified codes via line-by-line readings and discussion (56). A resulting coding scheme was refined with input from other team members (ENC and CMK), then applied to another four interviews (two adult, two caregiver), revised and formalized. Analysts applied this coding scheme to all remaining interviews. The broader coding team met regularly to resolve discrepancies and revise themes iteratively and reflexively. Inter-rater reliability was calculated (prior to resolutions) using percentage agreement (#inter-rater agreements / total #extracts coded; mean = 96%; range = 92–100%) or, for low prevalence codes (present in <14 interviews; n = 7), prevalence-adjusted, bias-adjusted kappa [mean = 0.96, range = 0.86–1.00; (57)]. The final set of themes and subthemes was organized and refined based on discussions with all co-authors. The authorship team comprised women and men of Caucasian, East Asian and South Asian descent, at early, mid, and senior career levels, with training and expertise in psychology, psychiatry, sociology, social work and epidemiology, as well as experience being on, or caring for someone on the autism spectrum.

Results

We identified 19 subthemes (each representing a coping strategy), three main themes, and one integrative theme (Figure 1, Table 3). Throughout this section, the term “participants” refers collectively to autistic adult and caregiver informants. More specific language is used to denote instances in which observations pertain primarily or solely to one group (e.g., autistic adults but not caregivers).

Engaging With Trauma

This theme encompassed seven subthemes in which participants actively addressed or managed trauma-related thoughts, emotions, or situations. Regarding deductive codes, problem-solving involved taking concrete steps to mitigate a traumatic situation: autistic adults reported setting interpersonal boundaries, for example with bullies or within toxic relationships. Parents noted children used problem-solving to navigate interpersonal problems and sensory situations, such as informing parents of overstimulating situations in advance. Both children and adults sought others' help to solve problems, such as reporting a situation to the school principal, or engaged in the problem more directly, for example proactively blocking a family member on social media to prevent further distress and distraction from one's studies. However, children tended to problem-solve by seeking others' help, whereas adults tended to engage with the problem more directly. Social support was the most commonly endorsed coping strategy, with every participant noting that autistic individuals relied on others for support in at least one traumatic situation. Support came from many sources, including family, friends, therapists, doctors, teachers, and pets; moreover, the types of support also varied. Some participants received practical support to complete specific tasks, such as assistance from a job coach in navigating the stressful process of job interviews. Others sought out emotional support, such as physical and emotional comfort from friends, family, and pets. Martha, a 37-year-old woman, spoke of the bond she had with her bird, who was “one of my reasons for living.” Children tended to receive support from family members (primarily parents) but also sought from friends, professionals such as a school counselor, social groups, and members of the community, such as neighbors or a librarian. Adults most often received support from professionals such as a job coach, lawyer, psychiatrist, or social worker, although they also reported being supported by friends and family. Participants also described expressing emotions, which entailed autistic people sharing trauma-related emotions with others as an outlet to process their trauma, rather than seeking practical support to address the traumatic situation itself. Adults and children alike mostly turned to family members, like parents, grandparents, or partners to express their emotions. However, adults also turned to professionals such as a job coach, or in one case, expressed their emotions to themselves. Participants noted both social support and expressing emotions had positive implications, especially when support came from those close to them, like parents, friends, or teachers.

Autistic individuals also engaged in self-criticism – blaming themselves (as opposed to their environment or circumstances) when attempting to understand the cause of their trauma and distress. Autistic adults attributed interpersonal trauma such as social exclusion or bullying to themselves. Parents described their children blaming themselves for their communication differences and for feeling “different” or disconnected from others. Several autistic adults also blamed themselves for encountering and reacting to abuse. Martha not only blamed herself for her sexual assault, but had also internalized the idea that sexual assault of women is socially accepted: “I felt so ashamed...and I felt stupid for getting upset at all because I know this happens to all women and nobody else lets it bother them.” Participants also described cognitive restructuring, or actively changing thought patterns to reframe traumatic experiences. This strategy was largely used by autistic adults, who described it as a way to reflect on past experiences with self-compassion. Some participants reported that cognitive restructuring occurred after learning that they were autistic provided a new perspective on their experiences. Others reported that friends, partners, job coaches, social workers, and therapists had helped, or directly taught them to reframe their experiences. Cognitive restructuring was largely used by adults; although one participant recalled that receiving their autism diagnosis as a child had helped them reframe their traumatic experiences.

Regarding inductive coping themes, rumination (repeated negative thoughts about the trauma) was noted by both parents, who described their children constantly worrying about past and anticipated sensory stimuli such as thunderstorms and haircuts, and autistic adults, who described replaying past interpersonal traumas. Although sometimes described as an attempt to understand trauma, rumination, similar to self-criticism, was typically associated with prolonged psychological distress for autistic adults and children. Lastly, participants reported self-growth/resilience (transforming past trauma into opportunities for growth or self-awareness), which typically occurred after a positive turning point, like meeting a spouse or a group of friends. Some autistic adults reported using past trauma to help others in similar situations; others described developing empathy toward others with social challenges. Adults and children found self-growth/resilience through the process of receiving their autism diagnosis, getting help from professionals such as therapists or counselors, and independent choices and actions, for example by deciding to forgive people who had hurt them in the past, or finding a purpose in life. Ultimately, self-growth/resilience captured positivity and meaning that could derive from traumatic experiences.

Disengaging From Trauma

This theme encompassed six subthemes involving autistic individuals withdrawing from trauma-related emotions, thoughts, or situations. Regarding deductive themes, several autistic adults and parents of autistic children reported problem avoidance – avoiding physical places, activities, or situations directly related to the trauma (e.g., staying away from school to avoid bullies). Both children and adults reported problem avoidance; however, this coping strategy was more often reported by children. Children largely reported avoiding places that were associated with their trauma, like home or school. Relatedly, participants described social withdrawal as a specific attempt for autistic people to distance themselves from others socially, in order to protect themselves from further challenges navigating social situations, social exclusion, or victimization. Participants also described nuanced forms of disengagement such as wishful thinking, in which autistic individuals used fantasy or daydreaming to escape trauma-related distress. Some autistic adults reported thinking of ways they could have fought back against bullies, or wishing they were born into a different life. Several parents described children engaging in wishful thinking about their autistic identity: Samara recalled her nine-year-old daughter telling her, “I wish I was like my [non-autistic] sister.”

Regarding inductive themes, participants described emotional avoidance – concealing and/or suppressing one's emotions. Autistic adults reported suppressing their emotions both internally (e.g., disconnecting from their pain, feeling numb) and outwardly (e.g., hiding their emotions, appearing “blank”) after receiving negative feedback from others for expressing their emotions in the past. Parents of younger children described their children ‘shutting down' and hiding their distress. Participants also described learned helplessness, in which autistic individuals adopted a hopeless mindset in relation to their trauma, in order to prevent continued feelings of being let down or disappointed. This often occurred when they felt their situation was beyond their control and would not change, such as being socially marginalized. A sense of helplessness was often described after repeated abuse or interpersonal betrayal. Learned helplessness was more often used by adults and older children after repeated and chronic traumas like prolonged bullying. Lastly, participants described self-protective behavior: remaining vigilant to avoid repeating past traumas. For example, one individual described carrying a backpack of personal items after being stranded as a child, while another described being wary of adults following childhood abuse by caregivers. As with learned helplessness, autistic adults and older children more commonly engaged in self-protective behaviors after repeated or chronic traumas.

Self-Regulatory Coping

This theme included six inductive subthemes involving attempts to calm oneself after experiencing a stressor. While some of these strategies showed potential overlap with Disengaging From Trauma, they were also described as attempts to manage internal trauma-related distress rather than, or in addition to the stressor itself. Some autistic individuals coped with substances, such as alcohol, food, and drugs. With the exception of prescribed medication, which was used by both adults and children, substances were largely used by adults and served varied functions. Participants noted marijuana and prescribed medication helped bring trauma-related thoughts, emotions or stress down to more manageable levels. On the other hand, illicit drugs and alcohol were typically described as a way to escape or numb distress. Participants described engaging in interests (e.g., music, writing, electronics) as a way to immerse oneself in activities that could bring joy, calm, and distraction from a stressor. Children engaged in interests such as video games, listening to music, television shows, and physical activity such as gymnastics, while adults reported engaging in hobbies such as attending science fiction conventions, writing, art, and dressing in costume. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors were described by parents and autistic adults as a way for autistic individuals to channel trauma-related emotions into physical action after reaching a breaking point. For example, parents speculated their child would bang their head when overwhelmed with emotional or sensory pain. Autistic adults also described cutting and burning themselves when they became overwhelmed by stressful situations, and engaging in suicidal thoughts to provide hope for an escape from their pain, and therefore temporary relief, when feeling despondent about their circumstances. Children tended to engage in self-injurious behaviors like head banging, or scratching and hitting themselves, whereas adults were more likely to engage in suicidal thoughts or attempts. Autistic adults reported, and parents speculated, that self-stimulating/self-soothing behaviors, such as rocking, pacing, and repetitive movements, helped autistic individuals calm themselves when distressed. Both children and adults engaged in stimming, although it was more common among children. Other forms of self-stimulating/self-soothing behaviors used by both adults and children included using sensory items such as beads or a weighted blanket, or finding a safe space/quiet room to decompress. Participants also noted emotional outbursts (with or without aggressive behavior), most often described as meltdowns, as a way to release overwhelming distress in traumatic situations. Situations ranged from sensory overstimulation, like getting a haircut, to interpersonal traumas, such as bullying. Emotional outbursts were largely used by children of varied ages and communicative abilities.

Diagnostic Overshadowing

Through the coding process, we observed that participants described overlap (and often confusion) between coping and autistic traits or autism-related behaviors. We therefore developed an integrative theme, Diagnostic Overshadowing, to highlight this issue, which was relevant to coping behaviors from the Disengaging from Trauma (social withdrawal, emotional avoidance) and Self-Regulatory Coping (emotional outbursts, self-injurious thoughts and behaviors, self-stimulatory/self-soothing behaviors) themes. Parents and autistic adults alike recalled the challenges arising from this overlap, including instances in which signs of trauma had been overlooked because they had been mislabelled as autism-related behaviors. For example, when describing her 5-year-old son's increasing social withdrawal following several traumatic hospitalisations, Maria stated, “I don't know if it's related to the trauma or related to just understanding that he's autistic.” Elsewhere, when discussing her 11-year-old son's emotional outbursts after experiencing abuse, Raisa noted, “I don't know what is the autism and what is the trauma…he already has autism but I feel like everything just quadrupled, like the reactions, the sensitivities.” Raisa also described the serious implications of this ambiguity for court proceedings:

“…it was like a double-edged sword–being autistic. You would think that they would…try to understand that part of him more, but instead they would try to use it like ‘oh no, that reaction is from the autism, it's not from the trauma'.”

Autistic adults also described how others could not only fail to recognize signs of trauma and coping, but could also view coping strategies (e.g., self-stimulatory/self-soothing behaviors) as problematic and needing to be “fixed”. Martha noted

“I think a big part of it is that we're already known for behaving oddly, and we're often in some sort of therapy or behavior modification to address it, so people are not expecting us to act normally. There's also a mindset of “fixing behavior problems”, so I think signs of distress or trauma are approached as just another irritating habit we need to be broken of, and nobody stops to think about why we're doing it.”

Discussion

This study interviewed verbally fluent autistic adults and caregivers of autistic children of varying ages and adaptive abilities to explore the varied ways in which autistic individuals cope with traumatic experiences, including but not limited to stressors outlined in PTSD criteria (e.g., abuse, life-threatening accident). To examine this research question from multiple angles and illuminate common themes, individuals with diverse experiences and characteristics were purposefully recruited.

We found that autistic people use multiple and varied strategies to cope with trauma, showcasing the multifaceted and flexible nature of coping (58). During interviews, participants described strategies within three main themes, largely consistent with existing theories of coping: Engaging with Trauma, Disengaging from Trauma, and Self-Regulatory Coping. A key component of coping frameworks is the distinction between approach vs. avoidance (11, 12), which aligns with our themes of engagement and disengagement. Interestingly, self-regulation has been proposed to cover a broad set of skills cutting across cognitive, emotional, and physiological domains, and to overlap with coping (59). Indeed, the Self-Regulatory Coping theme encompassed behaviors that could be framed as forms of disengagement (e.g., substances, engaging in interests, and self-injury), yet were consistently described by participants as autistic individuals' attempts to modulate internal thoughts or emotions. To capture and reflect these perspectives, we conceptualized these behaviors as serving a primarily regulatory function, while also recognizing the fluidity between self-regulation and other coping approaches.

We did not intend to organize themes based on the adaptive or maladaptive nature of each coping strategy. Nonetheless, in keeping with prior literature [see (11)], participants described disengagement strategies (e.g., learned helplessness) as ultimately enhancing distress and impairment. Some (e.g., social support, problem-solving) but not all (e.g., rumination) engagement strategies were characterized as protective, contributing toward resilience and post-traumatic growth. Consistently, social support and problem-solving are associated with post-traumatic growth in non-autistic adults (60), whereas brooding rumination may exacerbate traumatic stress symptoms for autistic adults (33). Relatedly, rumination and learned helplessness are known risk factors for depression (61, 62), which itself is a prevalent mental health concern among autistic people (63). Nonetheless, rumination was described by some autistic adults as a way of understanding past events, and by the parents of some children as a way of predicting and preventing future exposure. Consistent with findings in non-autistic samples (64, 65); self-regulatory coping strategies were associated with a mixture of positive and negative outcomes – for example, engaging in interests and self-stimulating/self-soothing behaviors could bring relief, yet also increase isolation or scrutiny by others. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors, including suicidal ideation, although dangerous and unsustainable in the long-term, were described by participants as bringing momentary relief from their distress – indeed, research has found that both non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation can function to regulate one's emotions, providing temporary reductions in stress and anxiety (66, 67) but also ultimately increasing the risk of a suicide attempt and suicide (68, 69). These nuances highlight the importance of considering coping strategies as having protective and detrimental aspects which vary across contexts and timeframes (70, 71), although further investigations are needed to evaluate the generalizability of these qualitative patterns.

We also observed that the utility and accessibility of coping behaviors may depend on personal and contextual factors, including an individual's developmental level, the nature and chronicity of their trauma, and the external resources available to them. Self-protective behavior, learned helplessness and emotional outbursts were often employed by children and adults in response to chronic stressors which felt beyond the individual's control, such as prolonged bullying or abuse, or a lack of protection from authority figures following trauma disclosure. On the other hand, problem-solving and cognitive restructuring were often used by older, verbally-able individuals, or those with strong social support networks, including people who recognized and responded to their needs, and who in some cases directly taught them how to use strategies. Overall, our findings suggest that – as with non-autistic people (72) – coping by autistic people takes many forms, may moderate relationships between PTE and outcomes, and is shaped by a confluence of individual and contextual factors. At the same time, existing theories and measures may require adjustment to accommodate additional complexities relevant to autistic people, such as including a broader range of coping behaviors. Systematic investigations of these nuances, particularly the effectiveness of different strategies, will be critical to developing tailored and effective interventions for this group (73). For example, future research could investigate the utility of programs designed to increase access to different forms of social support across multiple settings (e.g., at home, within schools, online, or in the community), as these could provide coping resources to autistic individuals, which may be especially valuable in the context of uncontrollable or chronic trauma. At the same time, programs that teach and scaffold the use of problem-solving and cognitive reframing strategies may prove beneficial in supporting autistic children and adults alike to cope with trauma more effectively, as has been found in other pediatric and neurodevelopmental populations (74–76). Importantly, such programs may be informed by future research seeking to identify the most effective forms of problem-solving or cognitive restructuring, as well as the traumatic contexts in which such strategies are most protective or beneficial.

Though not the primary aim of this investigation, a recurring theme which cut across the narratives of autistic adults and caregivers related to the challenges associated with differentiating coping from autism itself. We termed this theme Diagnostic Overshadowing as it pertained to the ways in which coping strategies may be misunderstood or overlooked due to the presence of an autism diagnosis. Participants described overlap between autistic behaviors and many identified coping strategies, including social withdrawal, emotional avoidance, emotional outbursts, self-stimulatory/self-soothing behaviors, and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Social withdrawal was described as a self-preserving response to bullying and marginalization, but at first blush could resemble and therefore be mistaken for differences in social understanding, communication, or motivation. Similarly, emotional avoidance could be a manifestation of alexithymia, which commonly affects autistic individuals (77), yet was described by participants as a purposeful attempt to minimize outward emotions, manage stress, and avoid scrutiny. Relatedly, in their conceptualization of masking, Pearson and Rose (78) suggest that for autistic people, a social context of stigma and victimization may underlie the pressure to suppress one's natural cognitive, emotional, and motor responses as a form of self-protection. Self-stimulatory/self-soothing behaviors involved modulating one's emotions by engaging in repetitive or sensory-focused activities. Restricted and repetitive activities are designated features of autism (2), yet were described herein as creating moments of relief to manage trauma-related distress. Consistent with these findings, prior research has shown that autistic adolescents and adults describe stimming as an important coping mechanism that helps them self-regulate when distressed (40, 41). Finally, self-injury and emotional outbursts are sometimes conceptualized as challenging behaviors associated with autism, yet were described by participants as outlets through which autistic individuals channeled overwhelming distress or responded to sensory pain. Existing research suggests that overwhelming and painful experiences of sensory stimuli can trigger meltdowns among autistic individuals (79). However, participants in the current study reported a variety of traumas, both sensory and interpersonal, that appeared to underlie emotional outbursts, highlighting the range of potential traumas that may be experienced as physiologically overwhelming and painful.

Diagnostic overshadowing is a barrier to the detection of mental health conditions in autistic individuals (80–82), particularly trauma (43, 83). Consistently, participants in this study illustrated the challenges and implications of traumatic coping being overshadowed for autistic individuals. Parents consistently described the difficulties they and others encountered when attempting to parse their child's traumatic reactions from behaviors commonly associated with autism, an issue also acknowledged by clinical experts (43, 44). Some highlighted the significant ramifications diagnostic overshadowing had in terms of the resources and legal recourse made available to them, while others reflected that not recognizing signs of coping caused themselves, educators, and healthcare workers to miss opportunities to intervene at the peak of their child's distress. These observations are consistent with studies documenting the reduced provision of trauma-focused treatments to autistic versus non-autistic youth, as well as a desire for training in trauma identification and treatment amongst autism-focused providers (29, 84). Similarly, autistic adults reflected on how their attempts to cope could be dismissed as part of their autism diagnosis. Some noted this could increase experiences of stigma and discrimination, which are linked with attempts to mask autistic behaviors and poorer well-being (78). Others highlighted the potential harm of intervention programs that aim to eradicate coping behaviors without considering their protective function.

The overlap between coping and autistic behaviors described here and in prior theoretical work (28, 29) raises important phenomenological questions about their nature, function and intersection. First, it is crucial to note that many of these coping behaviors (e.g., social withdrawal, emotional outbursts) are not unique to autism, and have been widely reported in studies of coping in the non-autism population (11). Nonetheless, the overlap of these strategies with autism-related behaviors may minimize this reality, such that the coping function of these behaviors is under-estimated. It may be that autism-related behaviors overlap with, or increase one's propensity toward a particular coping style; for example, emotion regulation difficulties could motivate varied attempts, such as meltdowns or self-injury, to control distress. Another possibility is that behaviors traditionally viewed as traits of autism also serve a self-regulatory function, and reflect autistic people's attempts to cope with stressors (both traumatic and non-traumatic). Recognizing this overlap may provide a more compassionate than pathologising lens through which to understand the experiences and actions of autistic people, with important implications for clinical practice. For example, notable changes in intensity or frequency of restricted and repetitive behaviors, social withdrawal, or emotional outbursts may signal attempts to cope with distress, alerting others to assess for past or ongoing trauma. In addition, intervention programs aiming to manage or reduce behaviors such as stimming may be untenable if they bar an autistic individual from accessing their coping resources. Relatedly, practitioners should consider if social withdrawal reflects a coping strategy that serves a self-preserving function when planning and delivering interventions to enhance social engagement and integration. In such cases, the clinician and client may need to identify alternative coping strategies that can be protective while still promoting social connection. Ultimately, instead of removing behaviors (and potentially valuable coping resources), autism- and trauma-informed care providers should collaboratively identify strategies that are sustainable, adaptive in the long-term and which best fit an individual and their circumstances in a way that respects their autonomy and differences.

Adding further complexity to the picture, many of the reported coping strategies also overlapped with designated symptoms of PTSD (2). For instance, rumination may reflect intrusive thoughts or memories of the trauma. Problem avoidance could represent a symptom of avoidance. Self-criticism, social withdrawal, and emotional avoidance could signify negative alterations in cognition and mood. Finally, emotional outbursts, self-protective behavior, and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors could indicate alterations in arousal and reactivity. To our knowledge, the conceptual and phenomenological distinctions between coping behaviors and PTSD symptoms have not been well-defined, yet research has consistently linked certain strategies (e.g., avoidance-based coping) with the subsequent development and severity of PTSD symptomatology (8, 9). We suggest the possibility that when used protractedly, certain coping strategies can themselves become symptoms of PTSD. Although beyond the scope of the current study, further defining the conceptual and temporal boundaries between coping and psychopathology will be of broader theoretical and clinical value.

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations of this study include a reliance on caregiver perspectives to explore the coping of younger children and individuals with communication challenges, which may introduce bias. Further research that systematically gathers and compares multi-informant (e.g., self, parent, teacher) reports of coping behaviors will illuminate converging and diverging perspectives on this phenomenon. Relatedly, we used stratified purposive sampling to select a heterogeneous sample of participants for this study, in order to capture a wide range of perspectives from autistic adults and caregivers. Although this sampling approach facilitated our examination of coping from diverse angles, allowing us to identify common themes across the sample despite its heterogeneity (85), future research investigating coping in more homogeneous samples of autistic people (e.g., among children, or adolescents specifically) may complement our broader observations with more nuanced findings regarding the coping of specific subgroups. On the other hand, limited racial diversity among autistic adults and underrepresentation of autistic girls, non-binary, or transgender individuals in the caregiver sample limited our ability to explore cultural and gender differences in experiences of trauma and coping (86–88). Further, this study focused on coping, rather than the range of traumatic responses possible amongst autistic individuals, which may include trauma resistance (not recognizing an event as traumatic) as well as resilience (risk and protective factors) and symptomatology. It is also important to note that the range of traumatic experiences encountered by autistic individuals varied as widely as the strategies they used to cope. Consistent with prior theoretical work (29) and as has been reported in recent research (44, 46, 52), individuals in this study experienced both PTSD-defined (e.g., physical and sexual abuse, life threatening accident) and broader (e.g., stigma and discrimination, sensory trauma, social confusion) traumas. We suggest the diversity of coping behaviors reported in this study reflects the diversity of traumatic experiences relevant to autistic individuals. Accordingly, future research should examine how coping behaviors may vary in response to traditionally recognized and distinct traumas. Finally, our qualitative observations, while fruitful in generating initial hypotheses and raising questions for further research, require replication and enumeration via quantitative investigation.

Conclusion

It is increasingly recognized that autistic people are disproportionately vulnerable to trauma. Compounding this vulnerability, a lack of access to autism- and trauma-informed mental healthcare may further contribute to physical and mental health disparities. Yet, our understanding of how autistic people respond to trauma, and whether their attempts to cope moderate post-traumatic outcomes, remains limited. Here, we identified a range of coping strategies used by autistic people, many of which are documented in the non-autism literature, and some of which may be more specific to, or appear to overlap with autism-related behaviors. Our findings highlight important considerations for conceptualizing coping in autism, including factors underlying differences in coping, and how aspects of autism may shape, overlap with, or overshadow coping behavior. Replicating these stakeholder-informed themes in future research may facilitate a more nuanced understanding of how autistic people respond to trauma, informing the development of more accurate measures to assess coping behaviors and their utility, as well as interventions to promote resilience. Ultimately, developing this understanding, supporting individual responses to trauma while also addressing environmental sources of trauma, and learning from the lived experiences of autistic people with trauma histories will be central to providing effective support for this population.

Data Availability Statement

The original datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they contain potentially identifying or sensitive personal information. Access to the de-identified datasets can be requested on reasonable demand via the senior author at Y21rZXJuc0Bwc3ljaC51YmMuY2Eu

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Drexel University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CK led the study conceptualization, study design, and data collection with guidance, and consultation from SL, SB, DR, and CN. AR and HP conducted the data analysis. EN-C, AR, HP, and CK interpreted the results with guidance from TG, and drafted the manuscript. EN-C and CK supervised the research project and writing. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript, including the thematic map, and approved the final version for publication.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (K23HD07472 to CK), John R. Evans Leaders Funds from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (#38787 to CK), and the Cordula and Gunther Paetzold Fellowship from the University of British Columbia (to EN-C).

Conflict of Interest

DR is a co-owner of M-CHAT, LLC. M-CHAT, LLC licenses the use of their intellectual property, the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) and M-CHAT Revised, with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F), for use in commercial products and collects royalties. She has a 50% share in the LLC. She also is on the advisory board for Quadrant Biosciences, Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the participants who contributed their valuable insights to this project, and also Dr. Paul Shattuck for his insights regarding study conceptualization and design.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.825008/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CSI, Coping Strategies Inventory; DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition; PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; PTSS, Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms; RAADS-14, Ritvo Autism and Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised Screen; SAMHSA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; TE, Traumatic Experience; THQ, Trauma History Questionnaire.

References

1. Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA's Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (HHS publication no. (SMA) 14-4884). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available online at: https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing (2013). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

3. Young De, Landolt AC. PTSD in children below the age of 6 years. Curr Psych Reports. (2018) 20:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0966-z

4. McCarthy J, Blanco RA, Gaus VL, Razza NJ, Tomasulo DJ. Trauma-and stressor-related disorders. In: Fletcher RJ, Barnhill J, Cooper SA, editors. DM-ID 2. Diagnostic Manual-Intellectual Disability: A Textbook of Diagnosis of Mental Disorders in Persons with Intellectual Disability. Kingston, NY: NADD Press (2017). p. 353–400.

6. Britt TW, Adler AB, Sawhney G, Bliese PD. Coping strategies as moderators of the association between combat exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. J Traum Stress. (2017) 30:491–501. doi: 10.1002/jts.22221

7. Elzy M, Clark C, Dollard N, Hummer V. Adolescent girls' use of avoidant and approach coping as moderators between trauma exposure and trauma symptoms. J Fam Violence. (2013) 28:763–70. doi: 10.1007/s10896-013-9546-5

8. Street AE, Gibson LE, Holohan DR. Impact of childhood traumatic events, trauma-related guilt, and avoidant coping strategies on PTSD symptoms in female survivors of domestic violence. J Traum Stress: Off Pub Int Soc Traum Stress Stud. (2005) 18:245–52. doi: 10.1002/jts.20026

9. Thompson NJ, Fiorillo D, Rothbaum BO, Ressler KJ, Michopoulos V. Coping strategies as mediators in relation to resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. (2018) 225:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.049

10. Badour CL, Blonigen DM, Boden MT, Feldner MT, Bonn-Miller MO. A longitudinal test of the bi-directional relations between avoidance coping and PTSD severity during and after PTSD treatment. Behav Res Ther. (2012) 50:610–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.06.006

11. Littleton H, Horsley S, John S, Nelson DV. Trauma coping strategies and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. J Trauma Stress. (2007) 20:977–88. doi: 10.1002/jts.20276

12. Tobin DL, Holroyd KA, Reynolds RV, Wigal JK. The hierarchical factor structure of the coping strategies inventory. Cognit Ther Res. (1989) 13:343–61. doi: 10.1007/bf01173478

13. Aldao A, Tull MT. Putting emotion regulation in context. Curr Opi Psychol. (2015) 3:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.03022

14. Moritz S, Jahns AK, Schröder J, Berger T, Lincoln TM, Klein JP, et al. More adaptive versus less maladaptive coping: What is more predictive of symptom severity? Development of a new scale to investigate coping profiles across different psychopathological syndromes. J Affect Disord. (2015) 191:300–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.027

15. Aupperle RL, Melrose AJ, Stein MB, Paulus MP. Executive function and PTSD: Disengaging from trauma. Neuropharmacology. (2012) 62:686–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.008

16. Wadsworth ME. Development of maladaptive coping: a functional adaptation to chronic, uncontrollable stress. Child Dev Perspect. (2015) 9:96–100. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12112

17. Amirkhan J, Auyeung B. Coping with stress across the lifespan: absolute vs. relative changes in strategy. J App Develop Psychol. (2007) 28:298–317. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2007.04.002

18. Aldwin C. Stress and coping across the lifespan. In S. Folkman (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping (pp. 15–34). New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2011). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.013.0002

19. Hartley SL, MacLean WE Jr. Perceptions of stress and coping strategies among adults with mild mental retardation: Insight into psychological adjustment. Am J Men Retard. (2005) 110:285–90. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110[285:POSACS]2.0.CO;2

20. Benson BA, Fuchs C. Anger-arousing situations and coping responses of aggressive adults with intellectual disabilities. J Intell Develop Disabil. (1999) 24:207–15. doi: 10.1080/13668259900033991

21. Hoover DW, Kaufman J. Adverse childhood experiences in children with autism spectrum disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2018) 31:128. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000390

22. Kerns CM, Newschaffer CJ, Berkowitz S, Lee BK. Brief report: examining, the association of autism and adverse childhood experiences in the National Survey of, Children's Health: the important role of income and co-occurring mental health, conditions. J Autism Dev Disord. (2017) 47:2275–81. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3111-7

23. McDonnell CG, Boan AD, Bradley CC, Seay KD, Charles JM, Carpenter LA. Child maltreatment in autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability: results from a population-based sample. J Child Psychol Psych. (2019) 60:576–84. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12993

24. Kerns CM, Rast JE, Shattuck PT. Prevalence and correlates of caregiver-, reported mental health conditions in youth with autism spectrum disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. (2020) 82:0–0. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13242

25. Taylor JL, Gotham KO. Cumulative life events, traumatic experiences, and psychiatric symptomatology in transition-aged youth with autism spectrum disorder. J Neurodev Disord. (2016) 8:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s11689-016-9160-y

26. Rumball F, Brook L., Happ,é F., Karl A. Heightened risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults with autism spectrum disorder: the role of cumulative trauma and memory deficits. Res Develop Disabil. (2021) 110:103848. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103848

27. Haruvi-Lamdan N, Horesh D, Golan O. PTSD and autism spectrum disorder: Co- morbidity, gaps in research, and potential shared mechanisms. Psychol Trauma Theory, Res, Pract, Policy. (2018) 10:290. doi: 10.1037/tra0000298

28. Haruvi-Lamdan N, Horesh D, Zohar S, Kraus M, Golan O. Autism spectrum disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder: an unexplored co-occurrence of conditions. Autism. (2020) 24:884–98. doi: 10.1177/1362361320912143

29. Kerns CM, Newschaffer CJ, Berkowitz SJ. Traumatic childhood events and autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. (2015) 45:3475–86. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2392-y

30. Berg KL, Shiu CS, Acharya K, Stolbach BC, Msall ME. Disparities in adversity among children with autism spectrum disorder: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. (2016) 58:1124–31. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13161

31. Maïano C, Normand CL, Salvas M, Moullec G, Aimé A. Prevalence of school bullying among youth with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. (2016) 9:601–15. doi: 10.1002/aur.1568

32. Nowell KP, Brewton CM, Goin-Kochel RP. A multi-rater study on being teased among Children/Adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their typically developing siblings: associations with ASD symptoms. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. (2014) 29:195–205. doi: 10.1177/1088357614522292

33. Golan O, Haruvi-Lamdan N, Laor N, Horesh D. The comorbidity between autism spectrum disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder is mediated by brooding rumination. Autism. (2021) 13623613211035240. doi: 10.1177/13623613211035240

34. Mehtar M, Mukaddes NM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in individuals with diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2011) 5:539–46. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.020

35. Haruvi-Lamdan N, Lebendiger S, Golan O, Horesh D. Are PTSD and autistic, traits related? An examination among typically developing Israeli adults. Comprehensive, psychiatry. (2019) 89:22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.11.004

36. Jahromi LB, Meek SE, Ober-Reynolds S. Emotion regulation in the context of frustration in children with high functioning autism and their typical peers. J Child Psychol Psych. (2012) 53:1250–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02560.x

37. Konstantareas MM, Stewart K. Affect regulation and temperament in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. (2006) 36:143–54. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0051-4

38. Dachez J, Ndobo A. Coping strategies of adults with high-functioning autism: A qualitative analysis. J Adult Dev. (2018) 25:86. doi: 10.1007/s10804-017-9278-5

39. Ghanouni P, Quirke S. Resilience and coping strategies in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Develop Disord. (2022) 3:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05436-y

40. Joyce C, Honey E, Leekam SR, Barrett SL, Rodgers J. Anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty and restricted and repetitive behaviour: Insights directly from young people with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. (2017) 47:3789–802. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3027-2

41. Kapp SK, Steward R, Crane L, Elliott D, Elphick C, Pellicano E, et al. ‘People should be allowed to do what they like': autistic adults' views and experiences of stimming. Autism. (2019) 23:1782–92. doi: 10.1177/1362361319829628

42. Hastings RP, Kovshoff H, Brown T, Ward NJ, Espinosa FD, Remington B. Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of preschool and school-age children with autism. Autism. (2005) 9:377–91. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056078

43. Kildahl AN, Helverschou SB, Bakken TL, Oddli HW. “Driven and tense, stressed out and anxious”: clinicians' perceptions of post-traumatic stress disorder symptom expressions in adults with autism and intellectual disability. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. (2020) 13:201–30. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2020.1760972

44. Kildahl AN, Helverschou SB, Bakken TL, Oddli HW. “If we do not look for it, we do not see it”: Clinicians' experiences and understanding of identifying post-traumatic stress disorder in adults with autism and intellectual disability. J App Res Intell Disabil. (2020) 33:1119–32. doi: 10.1111/jar.12734

45. Rumball F. A systematic review of the assessment and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Rev J Aut Develop Disord. (2019) 6:294–324. doi: 10.1007/s40489-018-0133-9

46. Kerns CM, Lankenau S, Shattuck PT, Robins DL, Newschaffer CJ, Berkowitz SJ. Exploring potential sources of childhood trauma: a qualitative study with autistic adults and caregivers. Autism. (2022) 3:637. doi: 10.1177/13623613211070637

47. Berkowitz SJ, Stover CS, Marans SR. The child and family traumatic < Collab>stress intervention: Secondary prevention for youth at risk of developing PTSD. J Child Psychol Psych. (2011) 52:676–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02321.x

48. Stover CS, Hahn H, Im JJ, Berkowitz S. Agreement of parent and child reports of trauma exposure and symptoms in the early aftermath of a traumatic event. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy. (2010) 2:159. doi: 10.1037/a0019156

49. Foa EB, McLean CP, Zang Y, Zhong J, Powers MB, Kauffman BY, et al. Psychometric properties of the post-traumatic diagnostic scale for DSM−5 (PDS−5). Psychol Assess. (2016) 28:1166. doi: 10.1037/pas0000258

50. Eriksson JM, Andersen LM, Bejerot S. RAADS-14 Screen: validity of a screening tool for autism spectrum disorder in an adult psychiatric population. Mol Autism. (2013) 4:49. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-49

51. Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. The Social Communication Questionnaire: Manual. Western Psychological Services. Torrance, CA (2003).

52. Rumball F, Happé F, Grey N. Experience of trauma and PTSD symptoms in autistic adults: risk of PTSD development following DSM-5 and non-DSM-5 traumatic life events. Autism Res. (2020) 13:2122–32. doi: 10.1002/aur.2306

53. International QSR. NVivo 12 (2018). Available online at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data- < Collab>analysis-software/support-services/nvivo-downloads

54. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

55. Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exe Health. (2019) 11:589–97. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

56. Lofland J, Snow D, Anderson L, Lofland LH. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning (2006).

57. Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol. (1993) 46:423–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90018-V

58. Aldwin CM, Yancura LA. Coping and health: a comparison of the stress and trauma literatures. Trauma Health: Physical Health Conseq Expos Ext Stress. (2004) 99–125. doi: 10.1037/10723-005

59. Aldwin CM, Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Taylor AL. Coping and self-regulation across the life span. In Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Smith J, Antonucci TC (Eds.), Handbook of Life-Span Development. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. (2011) (pp. 561–587). doi: 10.1002/9780470880166.hlsd002009

60. Joseph S, Murphy D, Regel S. An affective–cognitive processing model of post-traumatic growth. Clin Psychol Psych. (2012) 19:316–25. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1798

61. McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther. (2011) 49:186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006

62. Trindade IA, Mendes AL, Ferreira NB. The moderating effect of psychological flexibility on the link between learned helplessness and depression symptomatology: a preliminary study. J Contex Behav Sci. (2020) 15:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.12.001

63. Hollocks MJ, Lerh JW, Magiati I, Meiser-Stedman R, Brugha TS. Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2019) 49:559–72. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718002283

64. Aldao A, Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies: interactive effects during CBT for social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. (2014) 28:382–9. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.005

66. Al-Dajani N, Uliaszek AA. The after-effects of momentary suicidal ideation: a preliminary examination of emotion intensity changes following suicidal thoughts. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 302:114027. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114027

67. McKenzie KC, Gross JJ. Non-suicidal self-injury: an emotion regulation perspective. Psychopathology. (2014) 47:207–19. doi: 10.1159/000358097

68. Griep SK, MacKinnon DF. Does nonsuicidal self-injury predict later suicidal attempts? A review of studies. Arch Sui Res. (2020). 1–19. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2020.1822244

69. Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY. Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2016) 12:307–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204

70. Fischer R, Scheunemann J, Moritz S. Coping strategies and subjective well-being: context matters. J Happ Stud. (2021) 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10902-021-00372-7

71. Rottweiler AL, Taxer JL, Nett UE. Context matters in the effectiveness of emotion regulation strategies. AERA Open. (2018) 4:1–13. doi: 10.1177/2332858418778849

72. Stallman HM, Beaudequin D, Hermens DF, Eisenberg D. Modelling the relationship between healthy and unhealthy coping strategies to understand overwhelming distress: a Bayesian network approach. J Aff Disord Reports. (2021) 3:100054. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100054

73. Peterson JL, Earl RK, Fox EA, Ma R, Haidar G, Pepper M, et al. Trauma and autism spectrum disorder: review, proposed treatment adaptations and future directions. J Child Adoles Trauma. (2019) 12:529–47. doi: 10.1007/s40653-019-00253-5

74. Braun-Lewensohn O. Coping and social support in children exposed to mass trauma. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2015) 17:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0576-y

75. Gil KM, Wilson JJ, Edens JL, Workman E, Ready J, Sedway J, et al. Cognitive coping skills training in children with sickle cell disease pain. Int J Behav Med. (1997) 4:364–377. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0404_7

76. Salloum A, Overstreet S. Grief and trauma intervention for children after disaster: exploring coping skills versus trauma narration. Behav Res Ther. (2012) 50:169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.001

77. Kinnaird E, Stewart C, Tchanturia K. Investigating alexithymia in autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eu Psych. (2019) 55:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.09.004

78. Pearson A, Rose K. A conceptual analysis of autistic masking: Understanding the narrative of stigma and the illusion of choice. Autism Adulthood. (2021) 3:52–60. doi: 10.1089/aut.2020.0043

79. Fulton R, Reardon E., Kate R., Jones R. (2020). Sensory Trauma: Autism, Sensory Difference and the Daily Experience of Fear. Autism Wellbeing CIC.

80. Rosen TE, Mazefsky CA, Vasa RA, Lerner MD. Co-occurring psychiatric conditions in autism spectrum disorder. Int Rev Psych. (2018) 30:40–61. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1450229

81. South M, Costa AP, McMorris C. Death by suicide among people with autism: beyond zebrafish. JAMA network open. (2021) 4:e2034018. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34018

82. Stadnick NA, Brookman-Frazee L, Mandell DS, Kuelbs CL, Coleman KJ, Sahms T, et al. A mixed methods study to adapt and implement integrated mental healthcare for children with autism spectrum disorder. Pilot Feasibil Stud. (2019) 5:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40814-019-0434-5

83. Brenner J, Pan Z, Mazefsky C, Smith KA, Gabriels R. Behavioral symptoms of reported abuse in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in inpatient settings. J Autism Dev Disord. (2018) 48:3727–35. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3183-4

84. Stadnick NA, Lau AS, Dickson KS, Pesanti K, Innes-Gomberg D, Brookman-Frazee L. Service use by youth with autism within a system-driven implementation of evidence-based practices in children's mental health services. Autism. (2020) 24:2094–103. doi: 10.1177/1362361320934230

85. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA. 3rd Sage Publications (2002).

86. Yeh C, Inose M. Difficulties and coping strategies of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean immigrant students. Adolescence. (2002) 37:69–82.

87. Eschenbeck H, Kohlmann CW, Lohaus A. Gender differences in coping strategies in children and adolescents. J Indiv Diff. (2007) 28:18–26. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001.28.1.18

Keywords: trauma, autism (ASD), coping (C), quantitative analysis, internalizing

Citation: Ng-Cordell E, Rai A, Peracha H, Garfield T, Lankenau SE, Robins DL, Berkowitz SJ, Newschaffer C and Kerns CM (2022) A Qualitative Study of Self and Caregiver Perspectives on How Autistic Individuals Cope With Trauma. Front. Psychiatry 13:825008. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.825008

Received: 29 November 2021; Accepted: 15 June 2022;

Published: 14 July 2022.

Edited by:

Luigi Mazzone, University of Rome Tor Vergata, ItalyReviewed by:

Iliana Magiati, University of Western Australia, AustraliaAilsa Russell, University of Bath, United Kingdom

Daniel Shepherd, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand

Mirabel Pelton, Coventry University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Ng-Cordell, Rai, Peracha, Garfield, Lankenau, Robins, Berkowitz, Newschaffer and Kerns. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elise Ng-Cordell, ZWxpc2Uubmdjb3JkZWxsQHBzeWNoLnViYy5jYQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Elise Ng-Cordell

Elise Ng-Cordell Anika Rai1†

Anika Rai1† Connor M. Kerns

Connor M. Kerns