- 1Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia

- 2Department of Anatomy, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia

- 3Research and Training Department, Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Background: People living with HIV/AIDS have a higher rate of depression/depressive symptoms and this highly affects antiretroviral medication adherence. Therefore, much stronger evidence weighing the burden of depressive symptoms/major depression is warranted.

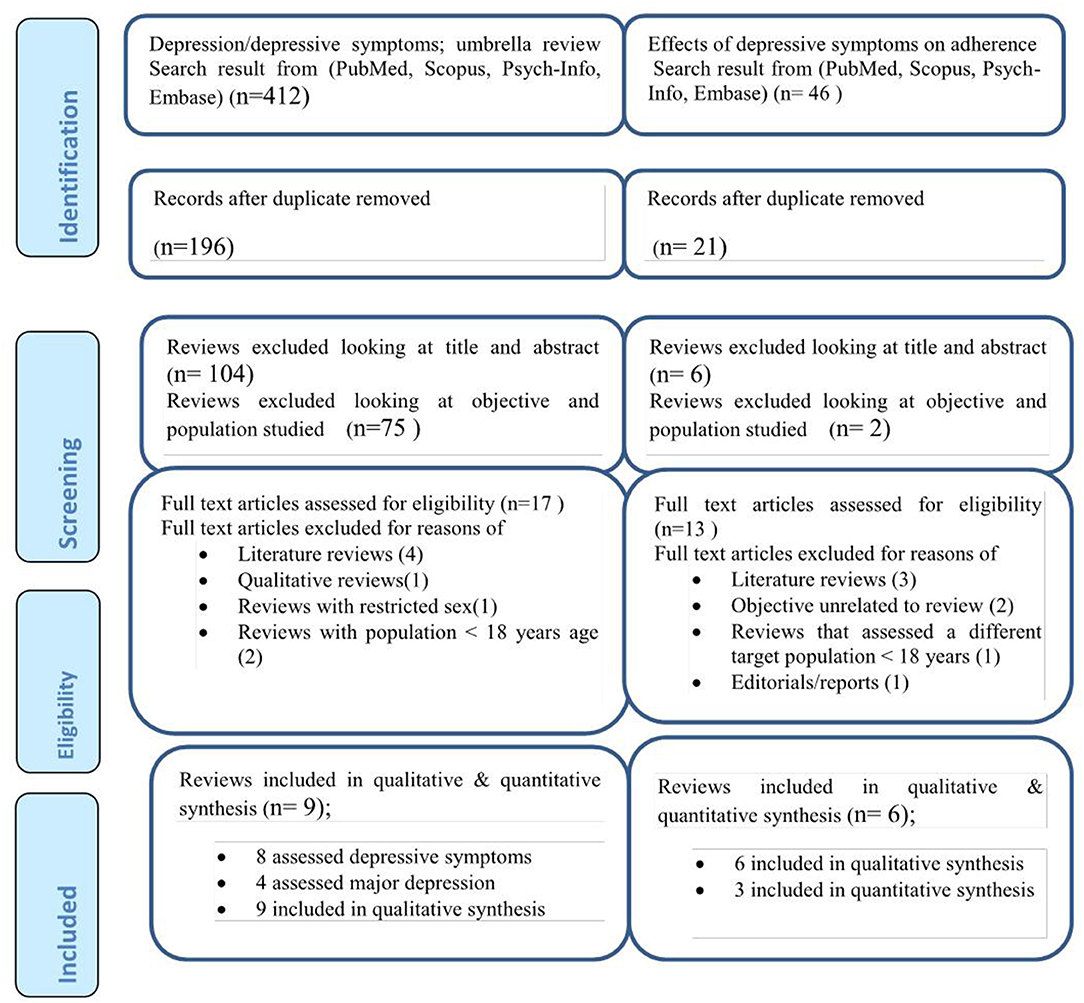

Methods: We investigated PubMed, Scopus, Psych-Info, and Embase databases for systematic review studies. A PRISMA flow diagram was used to show the search process. We also used the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist scores. A narrative review and statistical pooling were accompanied to compute the pooled effect size of outcome variables.

Results: Overall, 8 systematic review studies addressing 265 primary studies, 4 systematic review studies addressing 48 primary studies, and six systematic review studies addressing 442 primary studies were included for depressive symptoms, major depression, and their effect on medication non-adherence, respectively. Globally, the average depressive symptoms prevalence using the random effect model was 34.17% (24.97, 43.37). In addition, the average prevalence of major depressive disorder was obtained to be 13.42% (10.53, 16.31). All of the 6 included systematic review studies reported a negative association between depressive symptoms and antiretroviral medication non-adherence. The pooled odds ratio of antiretroviral medication adherence among patients with depressive symptoms was 0.54 (0.36, 0.72) (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.487).

Conclusion: Globally, the prevalence of depressive symptoms and major depression is high. There existed a high degree of association between depressive symptoms and antiretroviral medication non-adherence. So, focused intervention modalities should be developed and implemented.

Background

Individuals living with HIV/AIDS are more affected by this mental health problem than the general population up to 3 times higher (1). Depressive symptoms and the prevalence of depression are increased in people living with human immune virus (PLWHIV) and the presence of depressive symptoms or depression is associated with decreased adherence to antiretroviral medication.

The global prevalence of depressive symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS reaches 78% as evidenced from a review study by Uthman et al. (2). A sub-Saharan Africa review study that integrated 30 studies from 10 African countries revealed that the pooled prevalence of depression in patients with HIV/AIDS was 31.2% (3). Another sub-Saharan Africa review study revealed that depression symptom prevalence reaches 32% (4). A review study by Ayano et al. (5) on the east African HIV/AIDS population also obtained a high prevalence of depression (38%).

Major depressive disorder/depressive symptoms are linked to many undesired treatment outcomes in individuals living with HIV/AIDS (6), partially owing to the intermediating part of antiretroviral therapy (ART) non-adherence. It is known that depression is related to non-adherence in numerous long-lasting physical health conditions (7, 8); the probabilities of health non-adherence to medical prescriptions being more than 3 times higher in patients having depressive disorders/symptoms than patients not having depressive disorders (8). A systematic review and meta-analysis study consisted of 95 studies that reported that the presence of depressive disorder meaningfully affected ART medication non-adherence (9).

Results from a longitudinal study implied that reductions in depression symptoms over time were strongly connected with enhancements in ART treatment adherence and better treatment outcome (10). Another systematic review and meta-analysis study consisted of 29 studies and 12,243 participants living with HIV/AIDS reported that the effective treatment for depressive symptoms/disorder and emotional distress enhanced antiretroviral medication adherence and patients' overall treatment outcome (11).

The low level of policy consideration on depression among people living with HIV/AIDS and its effect on the antiretroviral medication adherence as well as the congruently inadequate implementation practice of interventions in this population might be attributed to the inadequacy of well-aggregated data regarding the extent of the problem. The need to develop a systematic review of reviews for a better evaluation, complementary data, and invention of evidence for policymakers and intervention planners is essential. Therefore, this umbrella review would have potential implications for different health sector stakeholders for having conclusive evidence regarding the problem and designing appropriate intervention plans and clinical guidelines.

Methods

Definition of an Umbrella Review

An umbrella review also known as a systematic review of systematic reviews is a synthesis that integrates previously done systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies, to provide very strong and concrete evidence in a given area. The evidence obtained from this review is essential for the development of health care policy, treatment, and prevention guidelines (12, 13). As with systematic review and meta-analysis studies, an umbrella review follows a systematic approach in searching the articles, quality appraisal, synthesis, and reporting of the results (14–16).

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria for Systematic Reviews

We searched PubMed, Scopus, Psych-Info, and Embase databases for systematic reviews for available eligible studies. The main objectives of the search for this umbrella review were the burden of depressive symptoms/depressive disorder and its effect on antiretroviral medication non-adherence.

Sample of the search strategy for depressive symptoms/major depressive disorder in PsycINFO via Ovid: (((depressive symptoms.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures]) OR (major depressive disorder.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures]))) OR (depression.mp. [mp = tile, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures]))) AND (HIV.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures]))) OR (AIDS.mp. [mp = tile, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures]))) OR (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.mp. [mp = tile, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures]))) AND (((review.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures]) OR (meta-analysis.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures] OR (systematic review.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, & measures]))). Furthermore, Google scholar, and the reference lists of on hand articles were investigated.

Outcome Measures and Their Operational Definitions

In this umbrella review, the systematic review studies that reported the following outcomes were incorporated.

Depressive Symptoms

In the present umbrella review, depressive symptoms among patients with HIV/AIDS were the first outcome variable. It was defined as the average effect size of depressive symptoms reported by a systematic review study or an estimate of depression obtained with varieties of screening tools in a meta-analysis study. Such measurement tools include but are not limited to the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D); Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale.

Depressive Disorder

In the present study, the depressive disorder was defined as the reported pooled estimate of depressive disorder by the included systematic review study or the estimated effect size of depression measured with varieties depression diagnostic tools, such as Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), and Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).

Effect of Depression on Antiretroviral Medication Non-adherence

One of our outcome variables is the effect of depression on antiretroviral medication non-adherence, and it was operationalized in the study as a measured effect size in terms of association measures between depression and antiretroviral medication non-adherence.

Inclusion Criteria

A study was included in the current umbrella review if it fulfills the following criteria [1] it must be titled with systematic review/meta-analysis in its heading [2]; depressive symptoms/major depressive disorder and its effect on antiretroviral medication non-adherence was the main objective [3]; incorporated at least two primary studies that investigated depressive symptoms/major depression and/or its effect on antiretroviral medication non-adherence [4]; the language of publications must be in the English language [5] if pooled effect size was calculated in the primary reviews, the model, the methodology, heterogeneity issues, and publication bias were indicated.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded systematic review articles that assessed depression/depressive symptoms and their effect on non-adherence to medication in HIV/AIDS patients at extreme age groups (adolescents and old age groups of patients). In addition, we excluded articles that were mere literature reviews that do not follow a standard guideline and articles published in non-English languages. Moreover, editorials reports, qualitative reviews, and reviews that assessed the outcome in either male or female sex only were excluded from the analysis.

Risk of Bias and Data Extraction

All systematic review and meta-analysis studies retrieved from the search databases were exported to an Endnote database manager. In the Endnote database manager, all articles imported from the different search databases were checked for duplicates and duplicate articles were then removed. The next step was assessing the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles before reviewing full texts. Systematic Review studies that meet the inclusion criteria after full-text review were then assessed using Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist scores for their quality. The checklist has-11 components which can be summed and scored from 11. An overall score of ≥8, 4–7, and score ≤ 3 was interpreted as high quality, medium quality, and low-quality studies, respectively. Two authors (MN & YZ) individualistically evaluated the quality of each systematic review study. The internal consistency between the two authors was 96% and agreement on the remaining 4% was touched by discussion. Relevant data from the included systematic review studies were extracted in a table having the following format: Name of author and year of publication; geographic coverage of the systematic review; the investigated databases; assessment tool for depressive symptoms/major depression; number of primary studies; the number of studied participants in the systematic review; main findings of the systematic review; and the AMSTAR score.

Data Synthesis

We synthesize the data separately for depressive symptoms/ major depressive disorder and its effect on antiretroviral medication non-adherence. A narrative review and statistical pooling (meta-analysis using the random effect model) were accompanied to compute the pooled effect size of depressive symptoms/ major depressive disorder and its effect on antiretroviral medication non-adherence. The presence of heterogeneity was confirmed using the Higgins method, with I2 statistics value ≥50 implying heterogeneity. The existence of publication bias was checked with a funnel plot and Egger's regression test. The Stata-11 software packages were used to compute the effect size (17).

Result

Search

We searched 412 articles concerning depressive symptoms/major depression in HIV/AIDS patients and 46 articles related to the association between depressive symptoms/major depressions and antiretroviral medication non-adherence. Once duplicate articles were removed and further screening for titles and abstracts were done, 17 systematic reviews for depressive symptoms/major depression prevalence and 13 systematic reviews on the effect of depressive symptoms/major depressions on antiretroviral medication non-adherence were assessed as full-text reviews. Eight systematic reviews studying the depressive symptoms/major depression in HIV/AIDS were excluded due to the following reasons: they were mere literature reviews (2), qualitative reviews (18), reviews addressing only the female sex (18), reviews conducted in HIV/AIDS patients with <18 years ago (19). Similarly, seven of the articles on the effect of depressive symptoms/major depressions on antiretroviral medication non-adherence were excluded as they were literature reviews (1), their objectives are unrelated to the review (19), reviews that assessed a different target population/ <18 years of age (18), and editorials/reports (18). Finally, 8 studies that assessed depressive symptoms (3–5, 20–24), of which 4 studies that assessed major depression (3, 5, 9, 23) were included in the umbrella review for the prevalence of depressive symptoms. Similarly, six studies (2, 3, 9, 11, 25, 26) that assessed the effect of depressive symptoms/depression on antiretroviral medication non-adherence were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Depressive Symptoms/Major Depression Prevalence

Characteristics of Included Reviews in the Umbrella Review

Overall, eight systematic review studies (3–5, 20–24) addressing 265 primary studies assessed depressive symptoms and four systematic review studies (3, 5, 9, 23) addressing 48 primary studies that assessed major depression were included in this umbrella review.

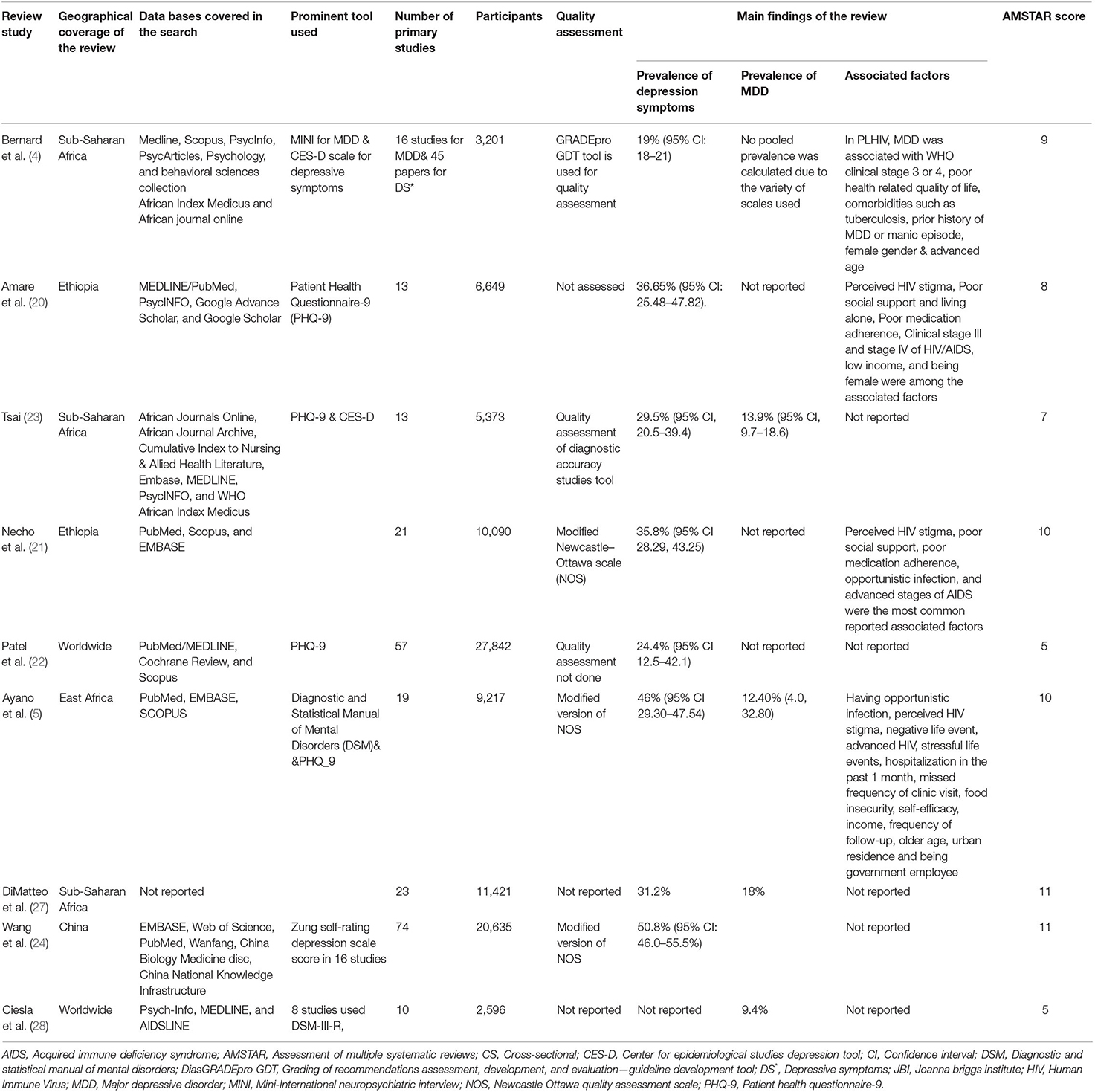

Considering the geographical coverage of the review, three reviews cover primary studies from sub-Saharan Africa (3, 4, 23) and two reviews cover primary studies from Ethiopia (20, 21). The number of original studies incorporated in the systematic reviews vary from as low as 10 studies with 2,596 participants (9) to as high as 74 studies with 20,635 participants (24). Patient health questionnaire-9(PHQ-9) was the most predominantly used tool to screen depressive symptoms in four of the review studies (5, 20, 22, 23). PubMed/MEDLINE, Psych INFO, Scopus, and EMBASE databases were the most frequently searched databases by the systematic review studies. Only six systematic review studies assessed the quality of primary studies using a standard quality assessment tool (see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of systematic reviews conducted on depression among HIV/AIDS patients included in this systematic review of reviews (N = 9).

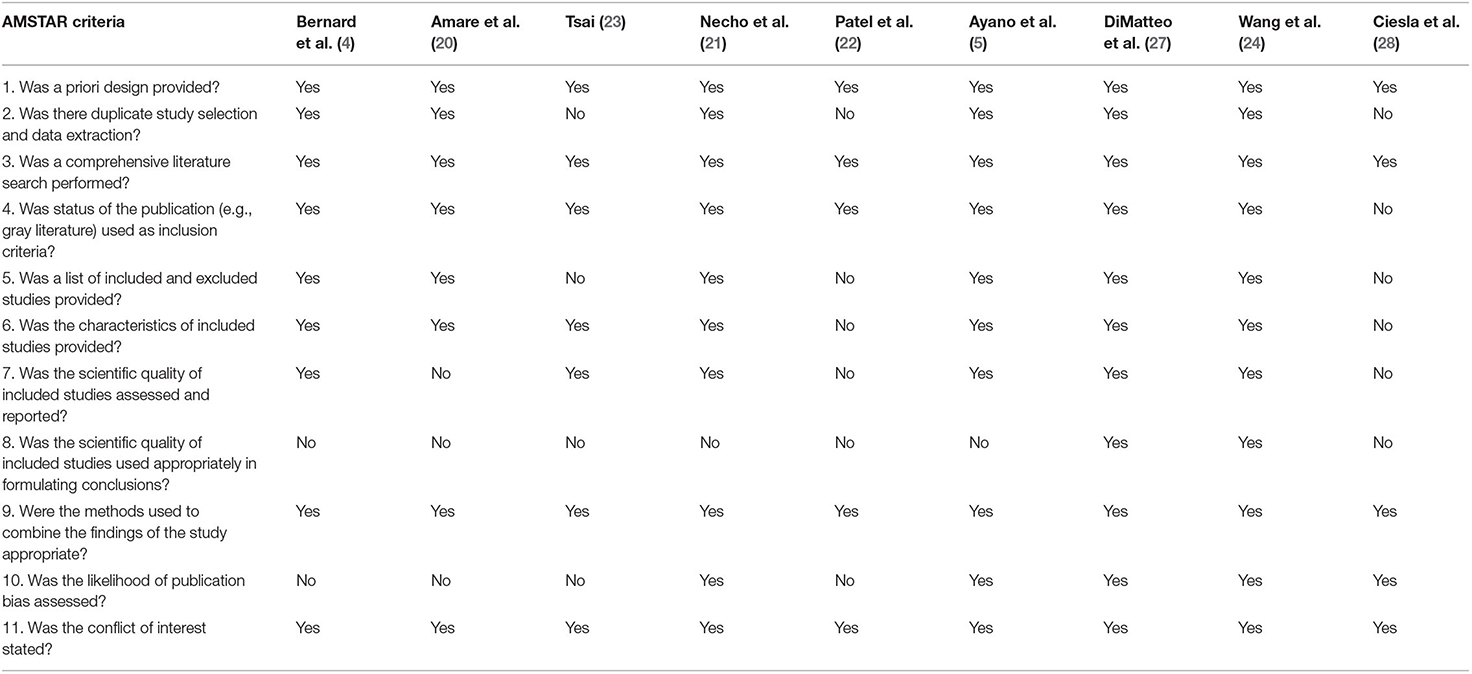

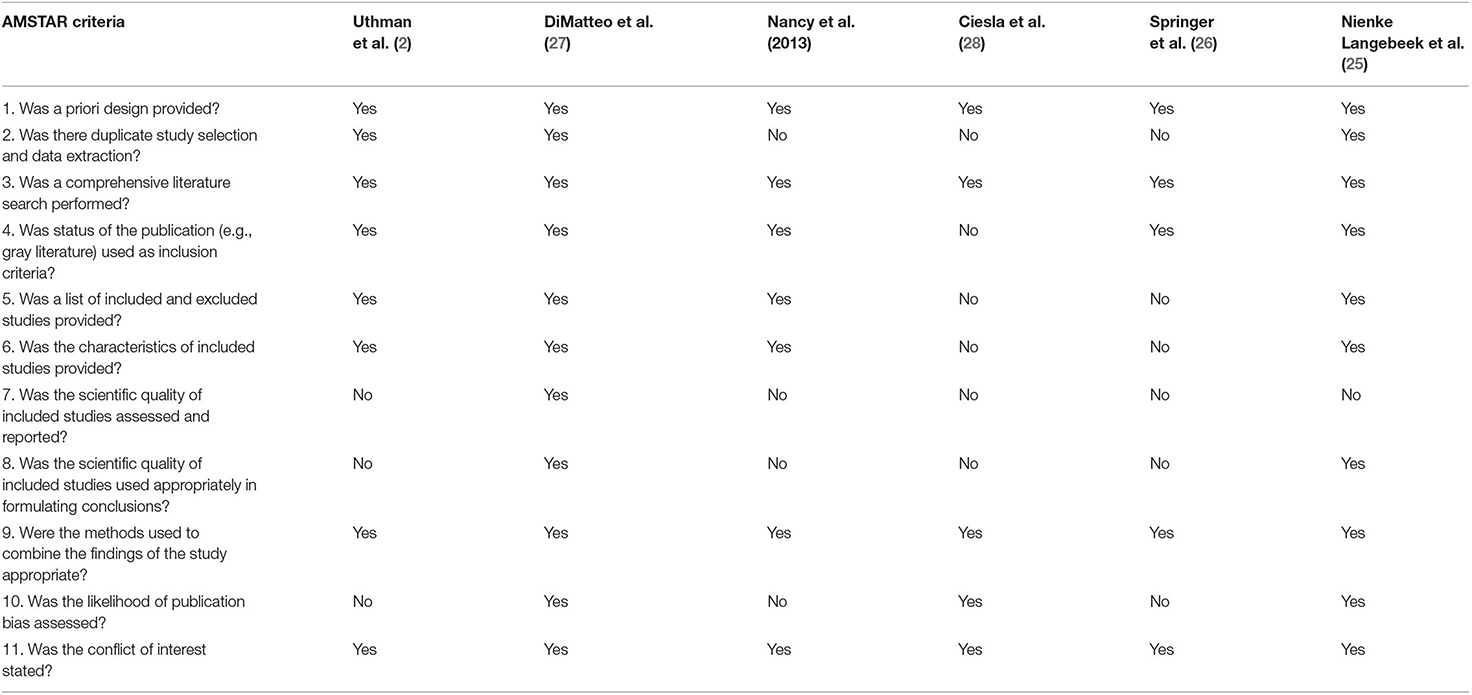

AMSTAR Score of Included Studies

Generally, the AMSTAR score assesses 11 components of a systematic review study; was a priori design provided? Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? Was a comprehensive literature search performed? Was the status of the publication (e.g., gray literature) used as inclusion criteria? Was a list of included and excluded studies provided? Were the characteristics of included studies provided? Was the scientific quality of included studies assessed and reported? Was the scientific quality of included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? Were the methods used to combine the findings of the study appropriate? Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? and was the conflict of interest stated? Considering these parameters, the AMSTAR score of included systematic review studies are as follows: six have high-quality scores and the remaining three have a medium score (see Table 2).

Table 2. AMSTAR score of included reviews on depressive symptoms/major depression and associated factors on HIV/AIDS patients.

The Pooled Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms and Major Depressive Disorder in the Umbrella Review

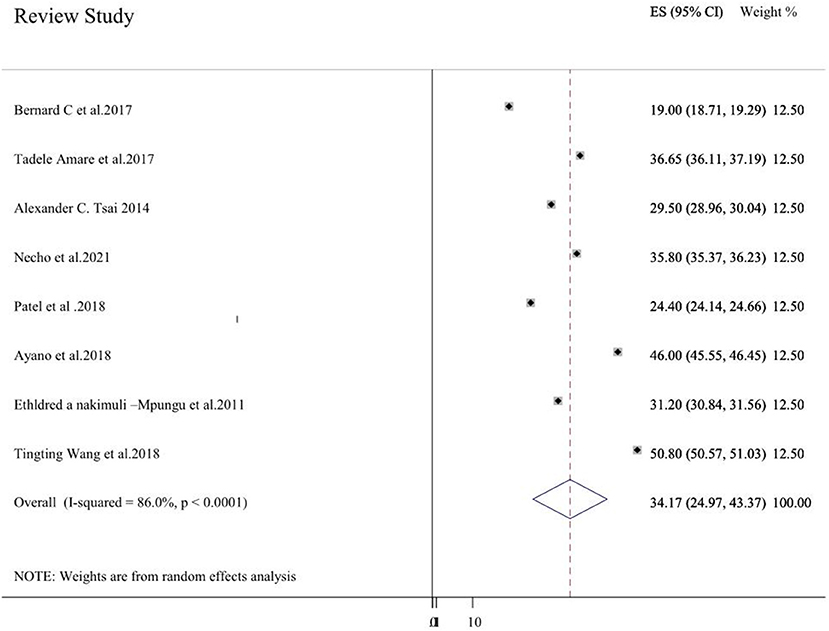

Eight systematic review studies (3–5, 20–24) had reported depressive symptoms in HIV/AIDS patients. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among the review studies ranges from 19% in Sub-Saharan Africa (4) to 50.8% in China (24). The average depressive symptoms prevalence of included systematic review using the random effect model was 34.17% (24.97, 43.37). This average prevalence has a significant heterogeneity (I2 = 86%, p < 0.001) from the difference among the incorporated systematic review studies (Figure 2). Three review studies were from sub-Saharan Africa (3, 4, 23), and the average depressive symptom prevalence of these studies was 26.57% (18.01, 35.12) (I2 = 90.9%, p < 0.001). Two systematic review studies were from Ethiopia (20, 21) and the average depressive symptom prevalence was 36.21% (35.38, 37.04) (I2 = 82.7%, p < 0.001).

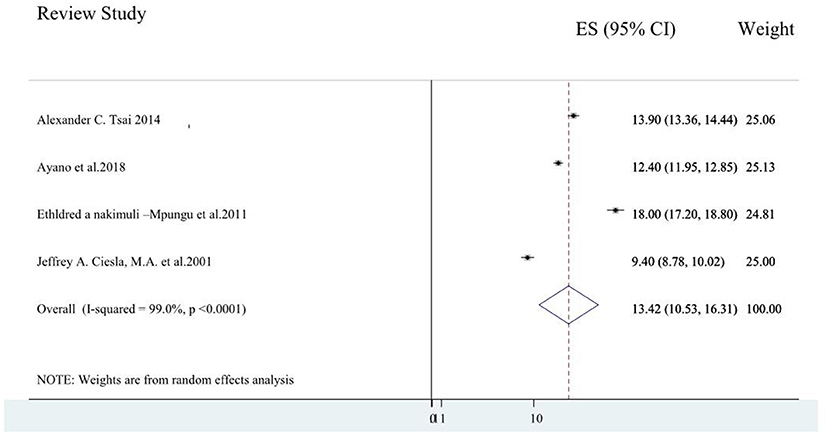

Four systematic review studies (3, 5, 9, 23) reported data on the major depressive disorder, and the average major depression prevalence among these studies varies from 9.4% of global prevalence (9) to 18% Sub-Saharan Africa (3). The average prevalence of the major depressive disorder among the four included systematic review studies were obtained to be 13.42% (10.53, 16.31) (I2 = 90%, p < 0.001; Figure 3).

Sensitivity Analysis

A one systematic review study leave-out at a time sensitivity analysis was done to explore whether a single systematic review study outweighed the average prevalence of depressive symptoms/major depressive disorder. However, the result obtained indicated that the average estimated prevalence of depressive symptoms/major depressive disorder obtained when each systematic review study is left out from pooled analysis was within the 95% confidence interval of the pooled depressive symptom/major depressive disorder prevalence. Therefore, the result of the average prevalence of depressive symptoms/ major depression in HIV/AIDS patients can be credible.

Publication Bias of Reviews for the Pooled Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms in the Included Reviews of the Umbrella Review

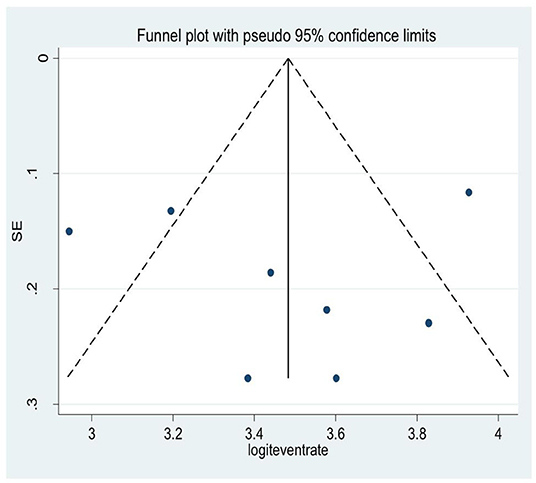

A snowball/visual inspection from the funnel plot for the average depressive symptom prevalence among HIV/AIDS patients showed that there exists an asymmetrical distribution of studies in the right and left margins of the funnel (Figure 4). This was further supported by the result of Egger's regression tests (P = 0.46). This implies there exist non-ignorable missing data during the searching or analysis process of the study.

Association of Depressive Symptoms on Medication Non-adherence Among HIV/AIDS Patients Included in This Umbrella Review

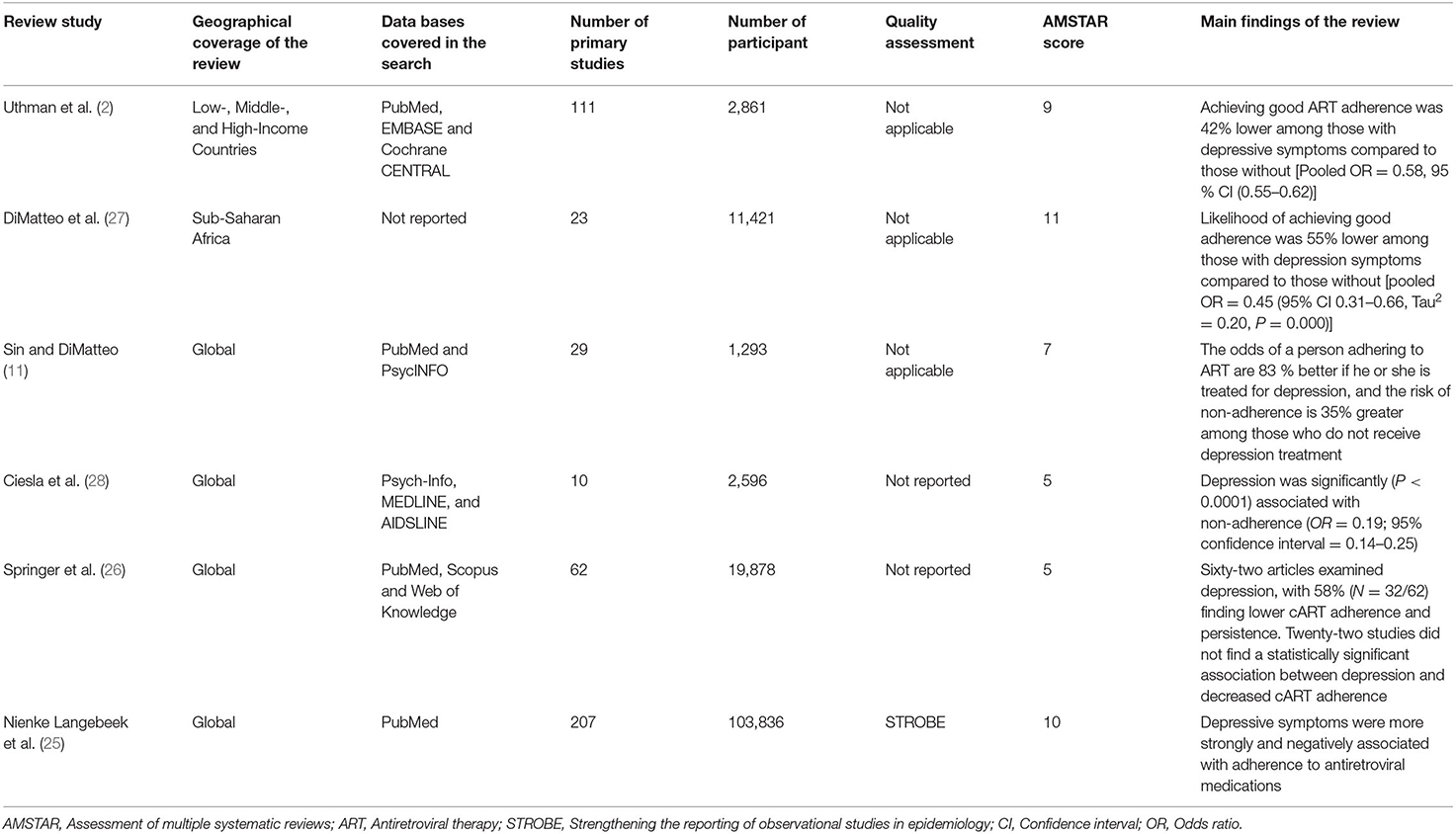

Characteristics of Included Reviews

We identified six systematic review studies (2, 3, 9, 11, 25, 26) that studied the effect of depressive symptoms on antiretroviral medication non-adherence. Except for one (3) which covers sub-Saharan articles, all of the remaining included systematic review studies cover articles from the global context. A total of 442 primary studies that assessed 141,885 participants were included. PubMed/Medline and Scopus were the most searched databases by the systematic reviews (see Table 3). Three of the systematic reviews had a high-quality score on the AMSTAR quality assessment criteria and the remaining three scored medium quality (see Table 4).

Table 3. Summary of systematic reviews conducted on the effect of depressive symptoms on medication non-adherence among HIV/AIDS patients included in this systematic review of reviews (N = 6).

Table 4. AMSTAR score of included reviews on effect of depressive symptoms on medication non-adherence among HIV/AIDS patients included in this systematic review of reviews.

The Pooled Odds Ratio for the Association of Depressive Symptoms on Antiretroviral Medication Adherence

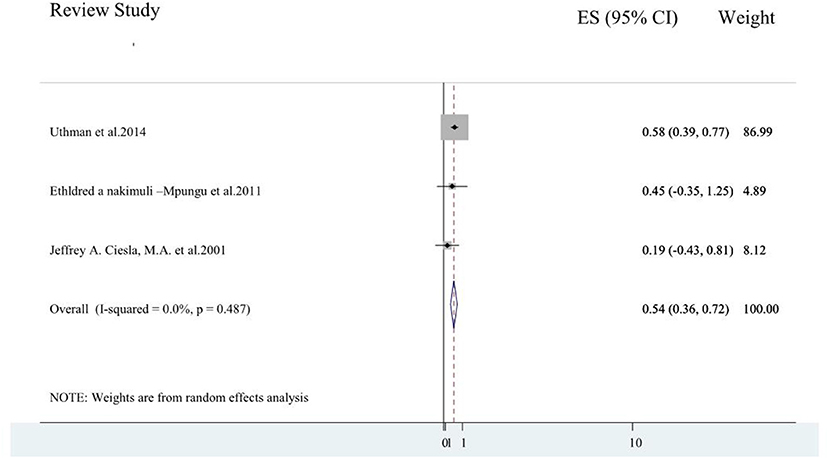

All of the included systematic review studies (2, 3, 9, 11, 25, 26) reported a negative association between depressive symptoms and antiretroviral medication adherence. For example, a review study by Uthman et al. (2) reported that patients with depressive symptoms were 42 % lower to adherent for their ART than those without depressive symptoms [Pooled OR = 0.58, 95 % CI (0.55–0.62)]. Similarly, a sub-Saharan review study (3) reported that depressed patients were 55% lower adherent to their medication as compared to those without depression [pooled OR = 0.45 (95% CI 0.31–0.66, Tau2 = 0.20, P = 0.000)].

Three of the six review studies (2, 3, 9) reported the strength of association between depressive symptoms and antiretroviral medication adherence. The pooled odds ratio of adherence among patients with depressive symptoms was 0.54 (0.36, 0.72) (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.487; Figure 5).

Figure 5. A forest plot for the systematic review of reviews of effects of depressive symptoms on antiretroviral medication adherence.

Discussion

Even though depressive symptoms/ major depression is highly associated with antiretroviral medication non-adherence, this has been poorly integrated into prevention policies and strategies. This could be due to the absence of concert aggregate evidence that could guide policymakers and intervention planners.

We accompanied these umbrella reviews to systematically generalize the worldwide burden of depressive symptoms/major depressive disorder and its impact on antiretroviral medication adherence.

Nine systematic review studies (3–5, 9, 20–24) that addressed 275 primary studies had reported depressive symptoms/major depression in HIV/AIDS patients. Of these systematic review studies, three assessed primary studies from sub-Saharan Africa (3, 4, 23), and two assessed primary studies from Ethiopia (20, 21). The remaining reviews cover primary studies from low and middle-income countries (22), East Africa (5), China (24), and the global context (9). The number of original studies incorporated in the systematic reviews vary from as low as 10 studies with 2,596 participants (9) to as high as 74 studies with 20,635 participants (24).

The prevalence of depressive symptoms among the review studies ranges from 19% in Sub-Saharan Africa (4) to 50.8% in China (24). The average depressive symptom prevalence among the included systematic review studies was 36.21%. This was in line with the pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms among rheumatoid arthritis patients where the pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms was 38.8% and 34.2% as measured with PHQ_9 and HADS, respectively (29). The pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms among chronic kidney patients was 39% (30) and was consistent with the current study. Additionally, this result is comparable to the average prevalence of depressive symptoms in cancer patients where 72 studies from 30 countries were pooled and resulted in 32.2% for depression symptom prevalence (31).

However, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in the present study was higher compared to the pooled estimated prevalence of depressive symptoms among general outpatient attendants (27%) (29). Moreover, the current finding was higher than the pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms among hypertensive patients (26.8%) (32). The higher rate of internalized as well as perceived stigma and socio-cultural discrimination in HIV patients could attribute to the higher magnitude of depressive symptoms (33).

On the contrary, the results of the present study were relatively lower as compared to the pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms among tuberculosis patients as reported with a systematic review and meta-analysis study of 25 studies and 4,903 participants where 45.19% of participants had depressive symptoms (34). Evidence suggests that the activation of enzymes, such as indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase, secondary to chronic inflammation as a result of TB infection reduces tryptophan and by this means affects serotonin production (35). Moreover, the psychosocial and health-related quality of life dysfunction that tuberculosis poses on patients would elevate the level of depressive symptoms (36, 37).

Four systematic review studies (3, 5, 9, 23) reported data on major depressive disorder, and the average major depression prevalence of these systematic review studies varies from 9.4% (9) to 18% in Sub-Saharan Africa (3). The average prevalence of the major depressive disorder among the four included systematic review studies were obtained to be 13.42%. A study on the prevalence of depression in the Community from 30 Countries between 1994 and 2014 obtained a result that was consistent with this study (38).

Moreover, six systematic reviews studies (2, 3, 9, 11, 25, 26) that included a total of 442 primary studies and 141,885 participants assessed the effect of depressive symptoms on antiretroviral medication adherence. Except for one (3) which covers sub-Saharan articles, all of these included systematic review studies cover articles from the global context. All of the included systematic review studies (2, 3, 9, 11, 25, 26) reported a negative association between depressive symptoms and antiretroviral medication adherence. For example, a review study by Uthman et al. (2) reported that patients with depressive symptoms were 42% lower adherent to their ART than those without depressive symptoms. Similarly, a sub-Saharan review study (3) reported that depressed patients were 55% lower adherent to their medication as compared to those without (pooled OR = 0.45).

Three of the six review studies reported the strength of association between depressive symptoms and antiretroviral medication adherence. The pooled odds ratio of adherence among patients with depressive symptoms was 0.54 (0.36, 0.72). This implied that people living with HIV/AIDS who had depressive symptoms were 46% less adherent to antiretroviral medication as compared to patients who had no depressive symptoms. A systematic review and meta-analysis studies reported that depressed patients had a loss of self-efficacy and the ability of decision-making capacity for treatment adherence which could attribute to this finding (39, 40).

Strength and Limitations of This Review of Reviews

These systematic reviews of reviews have the following strengths and limitations. The primary strengths of this review of reviews are the very broad and inclusive scope of the data and the applicability of the data to the problem. This umbrella review also yields an average burden of depressive symptoms/depression and its association with treatment adherence by uniting the result of multiple systematic reviews. A separate pooled analysis was also done for depression as a condition and depressive symptoms as measured using symptom checklists. This lays pivotal evidence for policymakers and intervention planners. The constraint of the study was that this systematic review of review did not address the possible contributing factors/meta-regression was not done for depressive symptoms/major depression which had to be addressed by researchers in the future. Moreover, high heterogeneity existed for review studies included in the umbrella analysis of depressive symptoms. Furthermore, as this study did not address the impact of treatment for depressive symptoms/depression on antiretroviral medication adherence, future research and researchers should investigate this phenomenon of interest. Last but not least, due to the wider contextual scope of coverage of the umbrella review, there might be a possibility of missing eligible studies during the search process. The challenges of comparisons between different methods were also another difficulty during the analysis.

Conclusion

This systematic review of reviews found a high pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms and major depression among people living with HIV/AIDS. The study also obtained that depressive symptoms affect patients' adherence to antiretroviral medication. These findings are very imperative as it suggests evidence for a variety of stakeholders that works for the betterment of the quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS. The primary stakeholders are clinicians who might benefit from the early screening and treatment of depressive symptoms/disorders in people living with HIV/AIDS. Next, policymakers and intervention players should encircle depression during the development of clinical guidelines, manuals, and prevention modules for people living with HIV/AIDS.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

MN premeditated the study, did the analysis and interpretation of the findings, and drafted the article. MN, BY, GA, and YZ accomplished the data search, extraction, and quality assessment of studies. YZ and MN revised the article. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AIDS, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; AMSTAR, Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews; ART, Antiretroviral Therapy; CS, Cross-sectional; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale; CI, Confidence Interval; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders; DiasGRADEpro GDT, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation—Guideline Development Tool; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute; HIV, Human Immune Virus; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NOS, Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; STROBE, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.

References

1. DeJean D, Giacomini M, Vanstone M, Brundisini F. Patient experiences of depression and anxiety with chronic disease: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. (2013) 13:1–33.

2. Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle-and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. (2014) 11:291–307. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0220-1

3. Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Bass JK, Alexandre P, Mills EJ, Musisi S, Ram M, et al. Depression, alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. (2012) 16:2101–18. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0087-8

4. Bernard C, Dabis F, de Rekeneire N. Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0181960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181960

5. Ayano G, Solomon M, Abraha M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiology of depression in people living with HIV in east Africa. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:254. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1835-3

6. Hartzell JD, Janke IE, Weintrob AC. Impact of depression on HIV outcomes in the HAART era. J Antimicrobiol Chemother. (2008) 62:246–55. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn193

7. Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, Suttorp M, Maglione M, McGlynn EA, et al. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. (2011) 26:1175–82. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1704-y

8. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. (2000) 160:2101–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101

9. Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2011) 58:181–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0B013E31822D490A

10. Wagner GJ, Goggin K, Remien RH, Rosen MI, Simoni J, Bangsberg DR, et al. A closer look at depression and its relationship to HIV antiretroviral adherence. Ann Behav Med. (2011) 42:352–60. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9295-8

11. Sin NL, DiMatteo MR. Depression treatment enhances adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. (2014) 47:259–69. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9559-6

12. Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, Dziedzic K, Treweek S, Eldridge S, et al. Achieving change in primary care—causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci. (2015) 11:1–39. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4

13. Langell JT. Evidence-based medicine: a data-driven approach to lean healthcare operations. Int J Healthc Manag. (2021) 14:226–9. doi: 10.1080/20479700.2019.1641650

14. Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2011) 11:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-15

15. Hasanpoor E, Hallajzadeh J, Siraneh Y, Hasanzadeh E, Haghgoshayie E. Using the methodology of systematic review of reviews for evidence-based medicine. Ethiopian J Health Sci. (2019) 29:26–39. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v29i6.15

16. Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid Implement. (2015) 13:132–40. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055

18. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (2011).

20. Amare T, Getinet W, Shumet S, Asrat B. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among PLHIV in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis, 2017. AIDS Res Treat. (2018) 2018:5462959. doi: 10.1155/2018/5462959

21. Necho M, Belete A, Tsehay M. Depressive symptoms and their determinants in patients who are on antiretroviral therapy in the case of a low-income country, Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2021) 15:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-00430-2

22. Patel P, Rose CE, Collins PY, Nuche-Berenguer B, Sahasrabuddhe VV, Peprah E, et al. Noncommunicable diseases among HIV-infected persons in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. (2018) 32 (Suppl. 1):S5. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001888

23. Tsai AC. Reliability and validity of depression assessment among persons with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2014) 66:503–11. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000210

24. Wang T, Fu H, Kaminga AC, Li Z, Guo G, Chen L, et al. Prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:160. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1741-8

25. Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, Vervoort SC, Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Richter C, et al. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. BMC medicine. (2014) 12:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0142-1

26. Springer SA, Dushaj A, Azar MM. The impact of DSM-IV mental disorders on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among adult persons living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. (2012) 16:2119–43. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0212-3

27. Abas M, Ali G-C, Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Chibanda D. Depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: time to act. Trop Med Int Health. (2014) 19:1392–96. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12382

28. Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. (2001) 158:725–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725

29. Wang J, Wu X, Lai W, Long E, Zhang X, Li W, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among outpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017173. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017173

30. Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, Tonelli M, Johnson DW, Nicolucci A, et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. (2013) 84:179–91. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.77

31. Pilevarzadeh M, Amirshahi M, Afsargharehbagh R, Rafiemanesh H, Hashemi S-M, Balouchi A. Global prevalence of depression among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2019) 176:519–33. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05271-3

32. Li Z, Li Y, Chen L, Chen P, Hu Y. Prevalence of depression in patients with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. (2015) 94:e1317. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001317

33. Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Sock Sci Med. (2007) 64:1823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006

34. Duko B, Bedaso A, Ayano G. The prevalence of depression among patients with tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2020) 19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00281-8

35. Yen Y-F, Chung M-S, Hu H-Y, Lai Y-J, Huang L-Y, Lin Y-S, et al. Association of pulmonary tuberculosis and ethambutol with incident depressive disorder: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. (2015) 76:505–11. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09403

36. Bhatia M, Bhasin S, Dubey K. Psychosocial dysfunction in tuberculosis patients. Indian J Med Sci. (2000) 54:171–3. doi: 10.18535/jmscr/v5i5.222

37. Bauer M, Leavens A, Schwartzman K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of tuberculosis on health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. (2013) 22:2213–35. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0329-x

38. Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x

39. Hindmarch T, Hotopf M, Owen GS. Depression and decision-making capacity for treatment or research: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. (2013) 14:54. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-14-54

Keywords: depression, depressive symptoms, HIV/AIDS, review of reviews, global

Citation: Necho M, Zenebe Y, Tiruneh C, Ayano G and Yimam B (2022) The Global Landscape of the Burden of Depressive Symptoms/Major Depression in Individuals Living With HIV/AIDs and Its Effect on Antiretroviral Medication Adherence: An Umbrella Review. Front. Psychiatry 13:814360. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.814360

Received: 13 November 2021; Accepted: 17 March 2022;

Published: 12 May 2022.

Edited by:

Rahul Shidhaye, Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences, IndiaReviewed by:

Glenn J. Treisman, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesCunxian Jia, Shandong University, China

Copyright © 2022 Necho, Zenebe, Tiruneh, Ayano and Yimam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mogesie Necho, bmVjaG9tb2dlczIwMTRAZ21haWwuY29t

Mogesie Necho

Mogesie Necho Yosef Zenebe

Yosef Zenebe Chalachew Tiruneh2

Chalachew Tiruneh2