95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 17 March 2022

Sec. Psychological Therapies

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.811665

Background: Innovative technologies, such as machine learning, big data, and artificial intelligence (AI) are approaches adopted for personalized medicine, and psychological interventions and diagnosis are facing huge paradigm shifts. In this literature review, we aim to highlight potential applications of AI on psychological interventions and diagnosis.

Methods: This literature review manifest studies that discuss how innovative technology as deep learning (DL) and AI is affecting psychological assessment and psychotherapy, we performed a search on PUBMED, and Web of Science using the terms “psychological interventions,” “diagnosis on mental health disorders,” “artificial intelligence,” and “deep learning.” Only studies considering patients' datasets are considered.

Results: Nine studies met the inclusion criteria. Beneficial effects on clinical symptoms or prediction were shown in these studies, but future study is needed to determine the long-term effects.

Limitations: The major limitation for the current study is the small sample size, and lies in the lack of long-term follow-up-controlled studies for a certain symptom.

Conclusions: AI such as DL applications showed promising results on clinical practice, which could lead to profound impact on personalized medicine for mental health conditions. Future studies can improve furthermore by increasing sample sizes and focusing on ethical approvals and adherence for online-therapy.

Increasing prevalent mental problems including depressive disorders, anxiety and related disorders are affecting the population's health conditions in a negative way. Frequency of mental health and artificial intelligence (AI) publications are expanding dramatically over the past few years (1). Deep learning (DL) methods would be important to handle complicated medical data-sets, building vigorous data-sets to share between institutions. Recent AI studies suggested promising directions for employing technology including deep learning in improving our understanding of mental health diagnosis and treatment (2, 3). Robotic interactions assist in providing the availability of information regarding individual emotional changes and keep daily records on cognitive changes (4). Technology such as Machine Learning has been implemented to solve mental health problems; emerging data in this field have provided insights into application of AI technologies in psychological treatments (5). Research regarding deep learning and its application in the medical ground is clinically increasingly relevant to therapeutic applications in treating mental disorders, which leads the aim of this review.

The innovation of machine learning endorses a data-driven approach in which a general-purpose program automatically learns elements from data (6), with no prior expertise needed (7). Methods developed based on deep learning in the machine learning field have effectively improved the current state of psychotherapy, and applied in a wide range of applications, such as identifying objects in images (8), recognizing speech (9), translating languages (10), understanding the genetic determinants of diseases (11), and predicting health status using electronic health records (12). With current technology covering online-treatments and robotic care for dementia and autism disorder (13, 14), AI applications in mental health can bring insights into new treatment approaches, Hilty et al. (15) provided evidence that AI brings opportunities to involve rural areas that have insufficient medical resources, better patient response, and save time for clinicians in the U.S. Additionally, DL is utilized in interventions for schizophrenia and is suggested to be effective in reducing anxiety by helping patients to detect emotional changes and thought patterns and to enhance flexible thinking styles. Fiske et al. (16) offer evidence that DL algorithms such as Tess, specifically designed for practical and accessible use of internet psychotherapy. Even though integrative psychological AI is not designed to replace the role of a trained therapist, it emerges as a feasible option for providing support for patients in need. People designed Tess to flag expressions that indicate emotional distress; the study found that it helped reduce depression and anxiety symptoms among users. Tess interprets psychological terms such as cognitive distortions and provides detailed advice for ascertaining and tackling difficult situations, which can be employed in areas that have fewer clinical resources. Nonetheless, a recent review by Horn and Weisz (17) argued that most psychological treatments focus on the aspects of cognition, behavior and emotion of a person much more than the biological features. These client features, which may vary adequately between individuals, apart from the interactions between these features and the environment, would need to be improved by AI to make it as precise and as useful as AI is for medical and pharmaceutical intervention. The objective of the review is to highlight potential applications of AI on psychological interventions and diagnosis, along with searching for new treatments, or complementary ways to improve effects of scale assessment or drug treatment.

Deep learning is a category of machine learning allows advanced problem-solving techniques of complicated non-linear pattern recognition of spatial samples. The proposition is to employ neural networks (NN) to learn a stratified representation of the data and continuously produce interpretable outcomes (18). Diagnosis for mental health disorders such as depression includes obtaining and extracting relevant data from DL databases to analyze patients who display classic symptoms of depression, such as feelings of sadness, emptiness, loss of interest or pleasure, and sleep disturbances. Recent studies (19, 20) reviewed the literature applying Deep Learning-based methods to analyze neuroimaging and EEG data for psychiatric disorders (including ASD, SZ, ADHD), DL technology would be a promising tool for the diagnosis and classification of patients with mental health disorders.

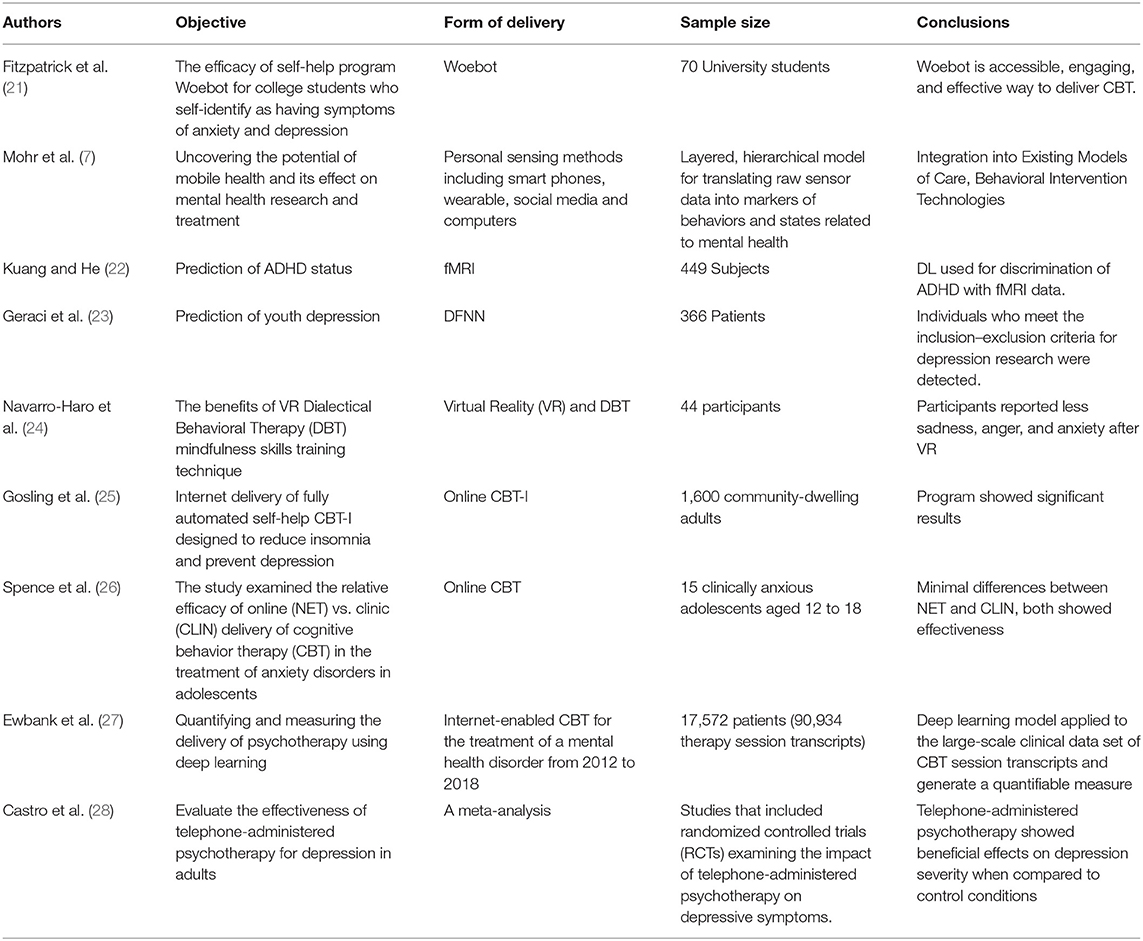

For this mini-review, articles published in English from January 2010 to December 2020 were searched in Pubmed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) and Web of Science using the terms “psychological interventions,” “diagnosis on mental health disorders,” “artificial intelligence,” and “deep learning.” We have based the criteria for selection on various components, the benefit of this approach is that we could narrow down a more precise range of articles. Publications were only included in the analysis if patients' datasets contained clinical, genetic, or medical information. Nine studies, which have been summarized in Table 1, met these inclusion criteria. We included studies showing positive results to discuss the constructive influences of different AI applications when implemented in psychological diagnosis and interventions.

Table 1. Summary of studies of artificial intelligence technology in psychological interventions and diagnosis.

AI is the theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks that usually require human intelligence, including components such as visual perception, speech recognition, and decision-making. Machine Learning is a type of artificial intelligence that includes systems that can learn from data, identify patterns, and make decisions with minimal human intervention, ML techniques include support vector machines, decision trees, neural networks, latent Dirichlet allocation, and clustering. ML focus on building systems that can automatically improve through experience using advanced statistical and probabilistic techniques (29). The application of ML in mental health has demonstrated a wide range of advantages across the fields of diagnosis, interventions and clinical administration (30). Researchers have applied ML to social media and online community information to decide the individual and linguistic and psychological features most predictive for successful alcohol abstinence (31). Deep Learning is a type of machine learning method based on learning data representations. Gkotsis et al. (32) revealed that Natural language processing of electronic health records in social media can be used to analyse people's mental health status on a daily basis. By implementing a deep learning approach, Gkotsis et al. (32) automatically recognized source of “in the moment” posts on social media platforms and classify posts related to mental illness following psychological disorder themes.

Deep learning (DL) has emerged as a way to examine large data-sets to reinforce risk detection (33). DL can screen through large data-sets including clinical files and social media information to recognize factors that might increase the risk of depression, including certain personality traits, such as low self-esteem or being too dependent, self-critical or pessimistic, or some traumatic or stressful events, or relatives with a history of mental disorders and so on.

Data collection and recognition allows clinical institutions to prevent suicidal attempts, and the analysis of prediction help to identify individuals in crisis so that we can intervene with emotional support, psycho-educational resources, and alerts for the need for emergency assistance (34). At the population level, algorithms can reduce suicidal attempt risks by identifying groups that are at risk or suicide hotspots, which help resource mobilization, policy reform or advocate local resources to help out and inform. The application of advanced machine learning technology to analyze the relations between different risk factors can improve early stages of mental health disorders and help early intervention and detection of patients with a tendency of getting ill ahead of time.

Zheng et al. (35) provides strong evidence of the connection between mental illness and attempted suicidal behavior. They conclude that the risk of suicide attempts among the people with one mental disorder at least is more than 10 times greater than those without. DL technologies are capable of detecting and intervening population who has the predisposition of attempting suicide, for example, Annette (36) highlighted salient risk factors like previous suicidal behavior. The diathesis-stress model of predicting population who are more vulnerable to mental health illnesses is being taken into consideration (37). The potential benefits that DL approaches can provide include precise risk hierarchy, informing specialists of the demand for mental health intervention, as a result, more integrated care plans can be developed. The method is likely to allow facilitation of the effectiveness of interventions to mitigate risk through targeting for providers in actual time. Therefore, developing and advancing personalized health care plans by analyzing available data from clinical institutions, record the intervention progress can help reducing suicidal risks.

Brain neural network plays an important role in the neuropathological mechanism of depression. DL learning about neuro-imaging (fMRI scans) helps to detect brain changes and subsequent mental disorders (38). Moreover, DL can learn features from the raw data without the need for a prior feature selection, resulting in a process that is more objective and less bias-prone. Kang et al. (39) demonstrated how integrative DL applications are used to differentiate panic disorder from other anxiety disorders using HRV (heart rate variability), thus using objective measurements to check biological differences and brain chemistry adjustment can be meaningful in the detection of mental health disorders, with DL technologies, identifications and detection could be more comprehensive in various ways.

Diagnosis for mental health disorders such as depression includes obtaining and extracting relevant data from DL databases to analyze patients who display classic symptoms of depression, such as feelings of sadness, emptiness, loss of interest or pleasure, and sleep disturbances. Online evaluation can help the specialist to quickly assess psychological state of patients, as mobile devices are more available nowadays and people can go through a psychological assessment at their convenience. Kalmady et al. (40) classified patients with schizophrenia using fMRI scans, best algorithm was Ensemble model: accuracy = 87%.

Depressed mood and loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities are the main characteristics of depression (41). The impact of depression can be extensive and disrupt social, occupational, and academic functioning. In China, it is estimated that about 100 million people suffer from various mental disorders, and 16 million are severely affected by their conditions. Research showed that Asians, especially those of Chinese descent are less likely to report their negative mood than individuals from Western cultures (42, 43). Not willing to approach for help could lead to a lower reporting rate for depression.

Psychotherapy generally termed as treating depression by talking about your condition and related problems with a therapist. Psychotherapeutic interventions are also known as talk therapy. Applying deep learning to large clinical data sets can provide significant insights into psychotherapy, informing people of the result of new treatments and helping standardize clinical practice and shed light upon interventions for relapse prevention (44). Pastor et al. (45) indicated that digital tools such as robotic partners or mobile devices can remind elderly people to take steps to reduce stress, reach out to family and friends, and getting long-term maintenance treatment. Nguyen et al. (46) used deep learning predictor with 2 hidden layers in DNN to identify whether patients with depression would respond favorably to bupropion. Squarcina et al. (47) suggested that patients' response to treatment vary across studies, might be because of inconsistent methodologies. Hence, deep learning algorithms could stimulate data-driven autoencoder to produce outcome effectively. Moreover, DL distinguishes between psychological interventions and brings out the best available treatment option.

Conversational technology has been increasingly integrated into the delivery of psychological interventions such as social therapy (48), cognitive behavioral therapy (21) and trauma therapy (49). Since the program responds to the presented dialogue, intervention delivery can be tailored to a patient's emotional state and clinical needs (48). Similar technologies, although preliminary, are being incorporated into smart phones to allow voice assistants to recognize and respond to user mental health concerns (50).

Internet-enabled CBT is effective for the treatment of depression clinically, and so is widely adopted in nowadays (27). Horn and Weisz (17) indicated that is not yet feasible to expect AI applications to be as contributive in psychotherapy compared to the extent in medical field, considering the striking difference between treatment response of psychotherapy and pharmacology. Unlike quantifiable and measurable treatments in medical practice (such as the dosage of prescribed drugs), the method of psychological interventions is sessions of confidential discussions between the patient and the clinician. Therapy can be in the form of online sessions, videos or workbooks accessible through internet descriptions and programs can be guided by a mental health professional independently. Ewbank et al. (27) illustrates the clinical relevance of supplementary online therapy; however, whether or not deep learning algorithms could be a substitute for a human therapist is unknown.

RCTs and reviews reported beneficial effects of exercise in moderately-depressed patients (51). Data from electronic health records can show early life adversity, stressful life events, and very proximal factors such as lifestyle, nutrition, and sport. Computers and Internet-based programs have great potential to produce more cost-effective psychological assessment and treatment. Taylor and Luce (2) stated that computer-assisted therapy appears to be as effective as a face-to-face treatment in treating anxiety disorders and depression, Internet support groups also may be effective and have advantages over face-to-face therapy. The results suggest that online assessment could reduce therapist contact time without adjusting or accommodating schedules. VR is a useful apparatus to improve exposure therapy, Botella et al. (52) demonstrated that virtual reality exposure therapy's (VRET) is effective for phobias. Parsons and Rizzo (53) showed large declines in anxiety symptoms following VRET. AI technology has also shown to be effective in improving the social skills of children with autism spectrum disorder (54). This means that children with ASD can practice, imitate and cooperate with their robotic partners that they have a greater chance of improving their interactions with adults. Such automated interaction aims to help children with ASD in need of acquiring proper skills such as social, self-reflection and management, with the aim of the children being able to apply the skills learned with the robot peer to their relationships with human peers.

AI technology holds great promises to transform mental health care and is not without potential pitfalls. Deep learning technology and online-interventions have significant meaning to mental health domain in that patients are given limited time during actual psychotherapy, compared to therapy hours being extended and accumulated through online-courses. Ewbank et al. (27) suggested that a therapist may accumulate abundant experience during his/her career which represents valuable expertise in CBT. Deep learning might allow us to make use of this knowledge to provide benefits to online interventions, and help improve the efficacy of psychotherapy. Shatte et al. (30) summarized the methods and applications of ML in mental health and found that four main application domains emerged: detection and diagnosis, prognosis treatment and support, public health, and research and clinical administration. DL applications can also be relevant in treatment studies in which new modes of intervention delivery methods can be explored. Durstewitz et al. (55) reviewed deep learning applications in psychiatry and suggested that they may provide insights similar to machine learning in psychiatry.

Other ethical considerations include severe consequences for online counseling (56). Particularly, online counseling and DL was noted as inappropriate for suicidal and psychotic clients, though online operations offer clinicians the chance to help people that were previously not able to be engaged in psychotherapy (57). Limitations are highlighted as studies point out contraindications for online therapy, noting that “severe pathology and risky behavior such as lethally suicidal conditions may not be appropriate for online work”. There are other limitations of online counseling, one of which is the inability to read non-verbal cues. The visual anonymity of much online counseling is often perceived as a strength; however, since body language plays a crucial role in face-to-face therapy, its absence online is likely to also bring challenges to practitioners and clients (58–60). Despite the reality that online counseling is developing very rapidly, there's very limited research focused on the phenomena, although more and more literature has emerged around online communication in general. Adherence to conversational agents is another factor to be considered when utilizing AI in psychotherapy (21). Taking findings from this more general research (61–64), however, problematic because counseling has many unique characteristics as a form of communication. In light of the prominence of evidence-based practice in the counseling industry, research specifically addressing the problems of online counseling practice is essential to access and flexibility as the strongest perceived advantages, identified by 85% of practitioners as strengths of online mental health services.

Overall, AI such as DL applications can be useful to treat mental disorders at the client's convenience. However, the field of AI and psychological interventions still have to be explored, and further research is needed to address the broader ethical and societal concerns of these technologies to negotiate the best research.

SZ, LZ, and JZ developed the framework for the mini-review. SZ and LZ wrote the manuscript and approved its submission. LZ edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (Grant No. 202002030262) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2017A030313809).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Graham S, Depp C, Lee EE, Nebeker C, Tu X, Kim HC, et al. Artificial intelligence for mental health and mental illnesses: an overview. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2019) 21:116. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1094-0

2. Taylor CB, Luce KH. Computer- and internet-based psychotherapy interventions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. (2016) 12:18–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01214

3. Su C, Xu Z, Pathak J, Wang F. Deep learning in mental health outcome research: a scoping review. Transl Psychiatry. (2020) 10:116. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0780-3

4. Savery R, Weinberg G. A survey of robotics and emotion: classifications and models of emotional interaction. In: Conference Paper (2020) 14838. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2007.14838

5. Luxton DD. Artificial intelligence in psychological practice: current and future applications and implications. Prof Psychol Res Pract. (2014) 45:332–9. doi: 10.1037/a0034559

6. Schmidhuber J. Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Netw. (2015) 61:85–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003

7. Mohr DC, Zhang M, Schueller SM. Personal sensing: understanding mental health using ubiquitous sensors and machine learning. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2017) 13:23–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-044949

8. Krizhevsky A.lex, Sutskever I.lya, Hinton, Geoffrey E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. (2017) 60:84–90. doi: 10.1145/3065386

9. Hinton G, Deng L, Yu D, Dahl GE, Kingsbury B. Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition: the shared views of four research groups. IEEE Signal Process Mag. (2012) 29:82–97. doi: 10.1109/MSP.2012.2205597

10. Sutskever I, Vinyals O, Le QV. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. Adv Neural Inform Proc Syst. (2014) 4:3014–112. Available online at: https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/5b070c85-03ed-3373-8933-333ac3886dec/

11. Xiong HY, Alipanahi B, Lee LJ, Bretschneider H, Merico D, Yuen RKC, et al. The human splicing code reveals new insights into the genetic determinants of disease. Science. (2015) 347:1254806. doi: 10.1126/science.1254806

12. Miotto R, Li L, Kidd BA, Dudley JT. Deep patient: an unsupervised representation to predict the future of patients from the electronic health records. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:26094. doi: 10.1038/srep26094

13. Rostill H, Nilforooshan R, Morgan A, Barnaghi P, Chrysanthaki T. Technology integrated health management for dementia. Br J Commun Nurs. (2018) 23:502–8. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2018.23.10.502

14. Ismail M, Barnes G, Nitzken M, Switala A, El-Baz A. A new deep-learning approach for early detection of shape variations in autism using structural mri. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). Beijing: IEEE (2017). 1057–61. doi: 10.1109/ICIP.2017.8296443

15. Hilty DM, Yellowlees PM, Cobb HC, Bourgeois JA, Neufeld JD, Nesbitt TS. Models of telepsychiatric consultation–liaison service to rural primary care. Psychosomatics. (2006) 47:152–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.2.152

16. Fiske A, Henningsen P, Buyx A. Your robot therapist will see you now: ethical implications of embodied artificial intelligence in psychiatry, psychology, and psychotherapy. J Med Internet Res. (2019) 21:e13216. doi: 10.2196/13216

17. Horn RL, Weisz JR. Can artificial intelligence improve psychotherapy research and practice?. Administr Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. (2020) 47:852–5. doi: 10.1007/s10488-020-01056-9

18. Zhang QS, Zhu SC. Visual interpretability for deep learning: a survey. Front Inform Technol Electr Eng. (2018) 19:27–39. doi: 10.1631/FITEE.1700808

19. Quaak M, van de Mortel L, Thomas RM, van Wingen G. Deep learning applications for the classification of psychiatric disorders using neuroimaging data: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage Clin. (2021) 30:102584. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102584

20. Mateo de Bardeci C, Cheng T, Soab C. Deep learning applied to electroencephalogram data in mental disorders: a systematic review. Biol Psychol. (2021) 162:108117. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2021.108117

21. Fitzpatrick KK, Darcy A, Vierhile M. Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (woebot): a randomized controlled trial. Jmir Mental Health. (2017) 4:e19. doi: 10.2196/mental.7785

22. Kuang D, He L. Classification on ADHD with deep learning. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Cloud Computing and Big Data. (2014). p. 27–32. doi: 10.1109/CCBD.2014.42

23. Geraci J, Wilansky P, de Luca V, Roy A, Kennedy JL, Strauss J. Applying deep neural networks to unstructured text notes in electronic medical records for phenotyping youth depression. Evid Based Mental Health. (2017) 20:83–7. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102688

24. Navarro-Haro V, López-del-Hoyo Y, Campos D, Linehan MM, Hoffman HG, García-Palacios A, et al. Meditation experts try virtual reality mindfulness: a pilot study evaluation of the feasibility and acceptability of virtual reality to facilitate mindfulness practice in people attending a mindfulness conference. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0187777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187777

25. Gosling JA, Glozier N, Griffiths K, Ritterband L, Thorndike F, Mackinnon A, et al. The goodnight study-online cbt for insomnia for the indicated prevention of depression: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. (2014) 15:56. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-56

26. Spence SH, Donovan CL, March S, Gamble A, Anderson RE, Prosser, et al. A randomized controlled trial of online versus clinic-based CBT for adolescent anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2011) 79:629–42. doi: 10.1037/a0024512

27. Ewbank MP, Ronan C, Valentin T, Sarah B, Ana C, Martin AJ, et al. Quantifying the association between psychotherapy content and clinical outcomes using deep learning. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:35–43. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2664

28. Castro A, Gili M, Ricci-Cabello I, Roca M, Mcmillan D. Effectiveness and adherence of telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2019) 1:514–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.023

29. Jordan MI, Mitchell TM. Machine learning: trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science. (2015) 349:255–60. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8415

30. Shatte AB, Hutchinson DM, Teague SJ. Machine learning in mental health: a scoping review of methods and applications. Psychol Med. (2019) 49:1426–48. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000151

31. Harikumar H, Nguyen T, Gupta S, Rana S, Kaimal R, Venkatesh S. Understanding behavioral differences between short and long-term drinking abstainers from social media. In: International Conference on Advanced Data Mining and Applications. Cham: Springer (2016). pp. 520–33.

32. Gkotsis G, Oellrich A, Velupillai S, Liakata M, Hubbard TJ, Dobson RJ, et al. Characterisation of mental health conditions in social media using Informed Deep Learning. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep45141

33. Biswas M, Kuppili V, Edla DR, Suri HS, Suri JS. Symtosis: a liver ultrasound tissue characterization and risk stratification in optimized deep learning paradigm. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. (2018) 155:165–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.12.016

34. Bernert RA, Hilberg AM, Melia R, Kim JP, Abnousi F. Artificial intelligence and suicide prevention: a systematic review of machine learning investigations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:5929. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165929

35. Zheng L, Wang O, Hao S, Ye C, Liu M, Xia M, et al. Development of an early-warning system for high-risk patients for suicide attempt using deep learning and electronic health records. Transl Psychiatry. (2020) 10:72. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0684-2

36. Annette ALB. Intervening to prevent suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. (2014) 1:165–7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70304-9

37. Spangler DL, Simons AD, Monroe SM, Thase ME. Evaluating the hopelessness model of depression: diathesis-stress and symptom components. J Abnorm Psychol. (1993) 102:592–600. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.4.592

38. Zhu G, Jiang B, Tong L, Xie Y, Wintermark M. Applications of deep learning to neuro-imaging techniques. Front Neurol. (2019) 10:869. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00869

39. Kang MJ, Kim SY, Na DL, Kim BC, Youn YC. Prediction of cognitive impairment via deep learning trained with multi-center neuropsychological test data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2019) 19:231. doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0974-x

40. Kalmady SV, Greiner R, Agrawal R, Shivakumar V, Narayanaswamy JC, Brown MRG, et al. Towards artificial intelligence in mental health by improving schizophrenia prediction with multiple brain parcellation ensemble-learning. NPJ Schizophr. (2019) 5:2. doi: 10.1038/s41537-018-0070-8

41. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Publication (2013).

42. Hofmann SG, editor. International Perspectives on Psychotherapy. Springer (2017). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56194-3

43. Lei XY, Xiao LM, Liu YN, Li YM. Prevalence of depression among chinese university students: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0153454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153454

44. Fulmer R, Joerin A, Gentile B, Lakerink L, Rauws M. Using psychological artificial intelligence (tess) to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health. (2018) 5:e64. doi: 10.2196/mental.9782

45. Pastor C, Gaminde G, Renteria A, Cornet G, Etxeberria I. Affective robotics for assisting elderly people. In: 10th European Conference for the Advancement of Assistive Technology (2009). 153–8. doi: 10.3233/978.1.60750.042.1.153

46. Nguyen KP, Fatt CC, Treacher A, Mellema C, Montillo A. Predicting response to the antidepressant bupropion using pretreatment fMRI. In: Predictive Intelligence in Medicine. Cham: Springer. ISBN: 978-3-030-32280-9 (2019).

47. Squarcina L, Villa FM, Nobile M, Grisan E, Brambilla P. Deep learning for the prediction of treatment response in depression. J Affect Disord. (2020) 281:618–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.104

48. D'Alfonso S, Santesteban-Echarri O, Rice S, Wadley G, Lederman R, Miles C, et al. Intelligent automated online social therapy for youth mental health. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:796. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00796

49. Tielman ML, Neerincx MA, Bidarra R, Kybartas B, Brinkman WP. A therapy system for post-traumatic stress disorder using a virtual agent and virtual storytelling to reconstruct traumatic memories. J Med Syst. (2017) 41:125. doi: 10.1007/s10916-017-0771-y

50. Miner AS, Milstein A, Schueller S, Hegde R, Mangurian C, Linos E. Smartphone-based conversational agents and responses to questions about mental health, interpersonal violence, and physical health. JAMA Intern Med. (2016) 176:719. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0400

51. Mead GE, Morley W, Campbell P, Greig CA, Mcmurdo M, Lawlor DA. Exercise for Depression. The Cochrane Library. John Wiley and Sons (2008). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6

52. Botella C, Fernández-Álvarez J, Guillén V, García-Palacios A, Baños R. Recent progress in virtual reality exposure therapy for phobias: a systematic review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0788-4

53. Parsons TD, Rizzo AA. Affective outcomes of virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety and specific phobias: a meta-analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2008) 39:250–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.07.007

54. Bird G, Leighton J, Press C, Heyes C. Intact automatic imitation of human and robot actions in autism spectrum disorders. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. (2007) 274:3027–31. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1019

55. Durstewitz D, Koppe G, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Deep neural networks in psychiatry. Mol Psychiatry. (2019) 24:1583–98. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0365-9

56. Chester A, Glass CA. Online counselling: a descriptive analysis of therapy services on the internet. Br J Guid Counsel. (2006) 34:145–60. doi: 10.1080/03069880600583170

57. Fonseka TM, Bhat V, Kennedy SH. The utility of artificial intelligence in suicide risk prediction and the management of suicidal behaviors. Australian N Zeal J Psychiatry. (2019) 53:954–64. doi: 10.1177/0004867419864428

58. Gravenhorst F, Muaremi A, Bardram J, Gruenerbl A, Mayora O, Wurzer G, et al. Mobile phones as medical devices in mental disorder treatment: an overview. Pers Ubiquitous Comput. (2015) 19:335–53. doi: 10.1007/s00779-014-0829-5

59. Ma Y, Xu B, Bai Y, Sun G, Zhu H. Daily mood assessment based on mobile phone sensing. In: Proceeding of the International Workshop on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks (BSN). London; Washington, DC: IEEE (2012). p. 142–47.

60. Ploug T, Holm S. Doctors, patients, and nudging in the clinical context-four views on nudging and informed consent. Am J Bioethics. (2015) 15:28–38. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2015.1074303

61. LiKamWa R, Liu Y, Lane ND, Zhong L. MoodScope: building a mood sensor from smartphone usage patterns. In: MobiSys '13: Proceeding of the 11th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services. Taipei; New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery (2013). p. 389–402.

62. Jones T, Glover L. Exploring the psychological processes underlying touch: lessons from the Alexander technique. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2014) 21:140–53. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1824

63. Cuzzolin F, Morelli A, Crstea B, Sahakian BJ. Knowing me, knowing you: theory of mind in AI. Cambridge Open Access. (2020) 50:1057–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720000835

Keywords: artificial intelligence, deep learning, machine, intervention, diagnosis

Citation: Zhou S, Zhao J and Zhang L (2022) Application of Artificial Intelligence on Psychological Interventions and Diagnosis: An Overview. Front. Psychiatry 13:811665. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.811665

Received: 11 November 2021; Accepted: 21 February 2022;

Published: 17 March 2022.

Edited by:

Luis Gutiérrez-Rojas, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Roopam Kumari, Department of Psychiatry, IndiaCopyright © 2022 Zhou, Zhao and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lulu Zhang, bGx6aGFuZzEzMDRAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.