- Department of Psychiatry and Narcology, Riga Stradinš University, Riga, Latvia

Schizophrenia is a psychiatric disorder characterized by positive, negative, cognitive and affective symptoms. Patient cooperation with health care professionals, compliance with the treatment regime, and regular use of medications are some of the preconditions that need to be met for a favorable disease course. A negative experience following the use of a first-generation antipsychotic to treat first-episode psychosis can negatively affect a patient's motivation for further medication use. In the clinical case reported here, cariprazine was able to restore one such patient's confidence in therapy and facilitated their cooperation with the physician, thereby ensuring effective control of negative and positive symptoms and good functioning for a period of 1 year. Cariprazine may be a good option for maintenance therapy following first-episode psychosis, especially in situations in which a patient has had a negative first experience associated with antipsychotic medication use.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a serious psychiatric disorder with a prevalence of ~1% in the population (1, 2). Positive symptoms of schizophrenia include delusions, hallucinations, abnormalities in how thoughts are linked together, thought insertion, withdrawal, thought broadcasting, and the belief that actions, feelings, or emotions are being controlled by external forces. Negative symptoms can include affective flattening, lack of motivation, loss of drive, lack of pleasure in any activities, poverty of speech, and diminished capacity to express feelings. Cognitive deficits may also be present with attention, language, and memory impairment. Affective symptoms may include depression and anxiety.

Throughout the course of schizophrenia, it is important to treat exacerbations of the positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms of the disease. Antipsychotics are effective in treating positive symptoms; however, treatment options for negative and cognitive symptoms are limited (3). Currently, most medications have not demonstrated sufficient efficacy in the treatment of negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia; although, cariprazine shows promise for the treatment of negative symptoms (4–6).

Premature termination of therapy leading to repeated psychotic episode is a serious issue when treating schizophrenia. More than 50% of patients with schizophrenia terminate their treatment following hospital discharge (7). Each subsequent psychotic episode adversely affects the overall course of the disease and reduces the patient's functional abilities. However, patients with schizophrenia are less frequently rehospitalized if they receive maintenance therapy and outpatient treatment (8). Unfortunately, a patient's initial experience with a psychiatric service (e.g., admission to a psychiatric hospital, receiving first-generation antipsychotics, and experiencing the side effects of antipsychotics) may disincentivize them to continue with their treatment (9). While it is difficult to determine a patient's non-adherence to treatment early on; medication adjustment and the minimization of side effects could increase treatment adherence (10).

Case Presentation

A 50-year-old male underwent emergency treatment for acute psychosis (delusions and hallucinations) in a psychiatric hospital and received haloperidol. The patient experienced the following side effects in the post hospital phase: acute dystonia, parkinsonism, dysarthria, and akathisia. The medication therapy was changed to a cariprazine-clozapine combination and was then continued with only cariprazine. A dose of 3 mg of cariprazine in monotherapy achieved stable improvement and full patient functionality for a period of at least 1 year.

Background History

A family history uncovered mental health problems in a sister, which was likely depression. The patient was born in a difficult labor, and presented fetal macrosomia. At an early age, the patient experienced difficulty pronouncing words and had attended speech therapy. He had average grades in school and was a loner. He continued his education at the university and attained a doctoral degree. For the past 20 years he has worked at a public institution at a senior level position.

The patient divorced 15 years ago and has two children. He currently lives with his father and sister and has had a girlfriend for several years with whom he shares common interests in astrology and the occultism.

The patient had rarely been ill during his lifetime and indicated only a gastric ulcer as a problem. Approximately 5 years ago, he suffered a concussion, but did not incur permanent damage. He does not consume alcohol or other addictive substances.

Diagnostic Assessment

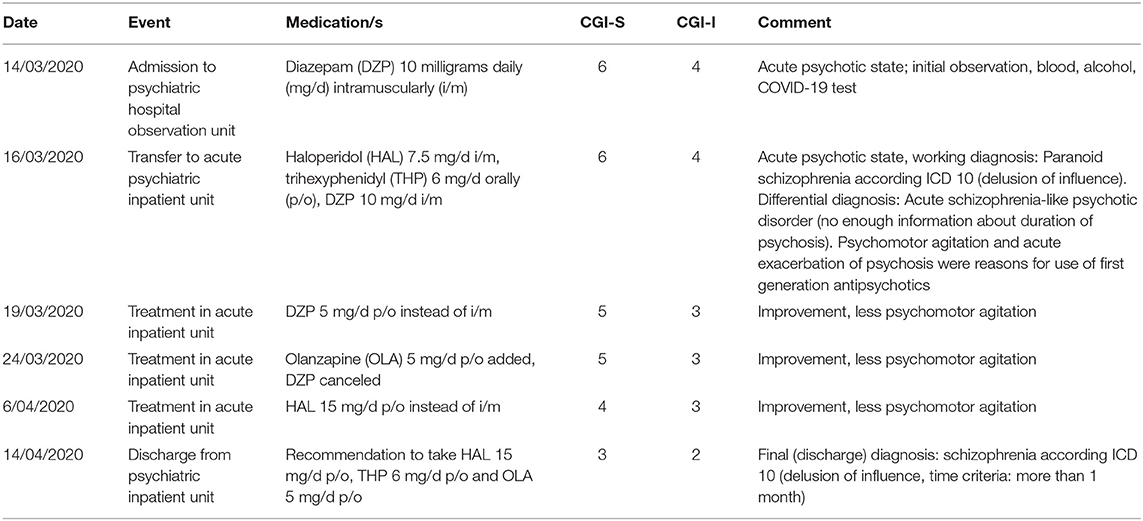

An overview of events, medications, evaluation, and associated comments about first hospital treatment episode is found in Table 1. The patient was initially admitted to an acute psychiatric inpatient unit at the instigation of the family as he had rapidly—within a period of 1 week—developed acute psychosis, psychomotor agitation, and thoughts of being cursed.

Table 1. Timeline of patient events, medications and scoring (CGI-S, CGI-I) across the first inpatient treatment episode.

Using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD 10) (11), a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia (F20.0) was made. Organic causes such as drug-induced psychosis, delirium, and metabolic disturbances were excluded. Differentiation from acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder (F23.2) was made based on detailed information from the patient and relatives concerning the duration of the psychosis. At the inpatient unit, the patient received haloperidol up to 15 mg/day (which was initially given intramuscularly in a dose 7.5 mg/day and then perorally 15 mg/day), 6 mg/day of trihexyphenidyl, and 5 mg of olanzapine in the evenings. The patient remained hospitalized for 31 days. Throughout this period, his acute psychotic symptoms lessened, although they were not eliminated. Some delusions remained, and the patient was suspicious.

The patient underwent a psychodiagnostic examination, and it was noted that his thinking was distinctly peculiar, atypical, and characterized by making judgments on the basis of assumptions understandable to himself but difficult for others to understand. The personality profile reflected fatigue, an apathetic state, a low energy level, and difficulty in motivating himself with purposeful actions. Interpersonal relations showed a tendency toward social introversion with avoidance and distancing behavior, a limited ability to express feelings and experiences, sensitivity to other people's attitudes toward him, cautiousness, and slight suspiciousness.

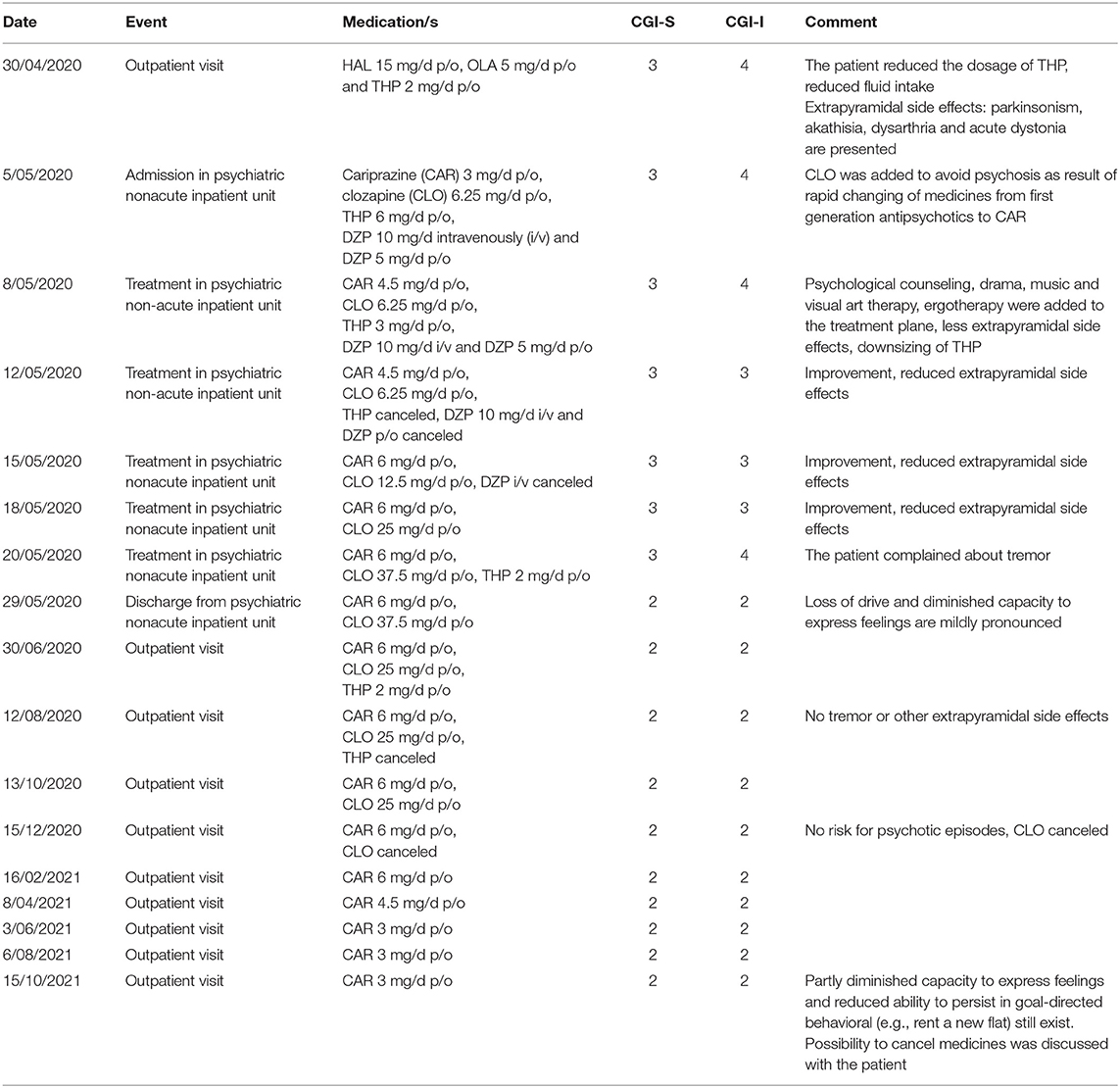

The patient was discharged from the hospital with recommendations to take 15 mg/day of haloperidol, 6 mg/day of trihexyphenidyl, and 5 mg of olanzapine in the evenings. The patient had planned to return to work. However, his condition deteriorated within ~2 weeks following hospital discharge. An overview of events, medications, evaluations, and comments about second hospitalization and outpatient treatment is available in Table 2. The patient began to exhibit side effects from the neuroleptics including parkinsonism, akathisia, dysarthria, and acute dystonia. This was partially the result of the patient reducing the dosage of trihexyphenidyl. In addition, without full understanding about the role of medications, he had little fluid intake due to a fear of sweating. He sought help from the outpatient service because of the pronounced neuroleptic side effects. His treatment was subsequently adjusted, and he was rehospitalized.

Table 2. Timeline of patient events, medications and scoring (CGI-S, CGI-I) across the outpatient treatment and second inpatient treatment episode.

Hospital treatment consisted of intravenously administered diazepam to alleviate the side effects, stopping the administration of haloperidol and olanzapine and, instead, introducing 6 mg/day of cariprazine with 37.5 mg of clozapine in the evenings, and 6 mg/day of trihexyphenidyl. Clozapine was added to avoid psychosis as result of the rapid changing of medicines from first generation antipsychotics to cariprazine. Given a treatment history that included an acute psychotic episode, possible future monotherapy appeared to be unlikely. A more likely option was a combination of cariprazine and clozapine. However, the patient received complex therapy during his hospital stay, including psychological counseling, drama, music, and visual art therapy (12), as well as ergotherapy sessions. The medication side effects resolved, and the patient regained confidence in therapy. Therefore, 6 mg/day of cariprazine was recommended following hospital discharge.

Current Status

After discharge, the patient returned to work. He currently sees a psychiatrist on a regular basis, and the dose of cariprazine has been gradually reduced to 3 mg/day in monotherapy. To date, his condition is stable. He has been fully functional for a year, with no positive or negative symptoms such as a loss of drive. However, a diminished capacity to express feelings are mildly pronounced. No additional psychological and social therapies have been needed. The patient is positive about his future treatment course; although, no final decision has been made concerning future medication use. While the patient is interested in quitting medication, there is the risk of future psychotic episodes or, in the case of a worsening mental health status, he might avoid treatment based on his negative experience.

Discussion

After analyzing the patient's disease course, there is evidence that, while the psychotic episode developed rapidly, there were premorbid signs suggestive of negative symptoms. His acute psychosis and agitation did not allow for a treatment method other than the use of first-generation neuroleptics (13). However, during the treatment process, the administration of olanzapine (14) was initiated with the aim of further transitioning to the use of second-generation antipsychotics.

Cooperation with a psychiatric patient is crucial for a successful treatment outcome. A patient's confidence in therapy is also important, and medication side effects do not facilitate trust in treatments regiments. However, negative, initial hospital treatment experiences can be avoided if proper information and psychoeducation is provided to the patient. It is possible that other atypical, antipsychotic medications would yield results that are similar to cariprazine in regard to negative side effects. However, the choice of cariprazine in this case was based on the patient's negative symptoms.

The patient was at high risk for avoiding further treatment given his negative experience following his first-episode psychosis. Therefore, further treatment needed to result in significantly fewer (and less severe) side effects, but with sufficient efficacy in addressing both his positive and negative symptoms. One important therapy goal is preventing recurrent psychotic episodes that can lead to deterioration in the overall course of the disease. In this case, the patient had a number of preconditions which suggested a sufficiently favorable disease course was possible. This included a late onset of psychosis, a high level of educational attainment, employment, and acute psychosis development (15). It was also extremely important for the patient to have confidence in further treatment and to trust the health care professionals. The choice of cariprazine proved to be effective as the patient's mental health and social functioning have been adequate for a year and continues to be stable.

There are several limitations concerning the approach taken toward this case. First no other clinical scales were used for patient assessment other than the Clinical Global Impressions Scale-Severity (CGI-S) and the Clinical Global Impressions Scale- Improvement (CGI-I). Second, during the first inpatient treatment course not enough information was provided to the patient. There was a low level of psychoeducation and not enough information was given regarding the role of each medication and his future treatment. Providing this information must play role for successful treatment. Finally, the patient did not receive any antipsychotic medications other than cariprazine, haloperidol and, periodically, olanzapine and clozapine. Therefore, we cannot know the possible results of medications other than cariprazine.

Cariprazine should be considered an antipsychotic of choice for maintenance therapy in patients who have experienced first-episode psychosis, especially if the patient has had a negative experience associated with medication side effects.

Patient Perspective

The patient is fully satisfied about current treatment, but also remember side effects from first generation antipsychotics. He is still cautious about treatment and hope quitting medication in a near future. The patient is positive about future, employment, relationship.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The patient provided written informed consent. Institutional approval was not necessary for publication.

Author Contributions

MT designed the case report, gathered the data, wrote, and edited the manuscript.

Funding

The open access fee is covered by Prescott Medical Communications Group.

Conflict of Interest

The author has received financial benefits for participation in boards, and as a speaker from the pharmaceutical companies: Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, Gedeon Richter, Olainfarm, Grindex, and Medochemie.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Cowen P, Harrison P, Burns T. Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2012). p. 818.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluver (2015). p. 1472.

3. Mäkinen J, Miettunen M, Isohanni M, Koponen H. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review. Nord J Psychiatry. (2008) 62:334–41. doi: 10.1080/08039480801959307

4. Citrome L. Cariprazine for acute and maintenance treatment of adults with schizophrenia: an evidence-based review and place in therapy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2018) 14:2563–77. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S159704

5. Rodriguez CJ, Sahlsten SJ, Hjorth S. Case report: cariprazine in a patient with schizophrenia, substance abuse, and cognitive dysfunction. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:727666. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.727666

6. Fleischhacker W, Galderisi S, Laszlovszky I, Szatmari B, Barabassy A, Acsai K, et al. The efficacy of cariprazine in negative symptoms of schizophrenia: Post hoc analyses of PANSS individual items and PANSS-derived factors. Eur Psychiatry. (2019) 58:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.01.015

7. Vega D, Acosta FJ, Saavedra P. Nonadherence after hospital discharge in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a six-month naturalistic follow-up study. Compr Psychiatry. (2021) 108:152240. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152240

8. Barnes TR, Drake R, Paton C, Cooper SJ, Deakin B, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychophar. (2020) 34:3–78. doi: 10.1177/0269881119889296

9. Neef J, Palacios DS. Progress in mechanistically novel treatments for schizophrenia. RSC Med Chem. (2021) 12:1459–75. doi: 10.1039/d1md00096a

10. Leijala J, Kampman O, Suvisaari J, Eskelinen S. Daily functioning and symptom factors contributing to attitudes toward antipsychotic treatment and treatment adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:37. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03037-0

11. World Health Organization. ICD-10 Version:2010. (2010). Available online at: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2010/en (accessed November 18, 2021).

12. Attard A, Larkin M. Art therapy for people with psychosis: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:1067–78. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30146-8

13. Keating D, McWilliams S, Schneider I, Hynes C, Cousins G, Strawbridge J, et al. Pharmacological guidelines for schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparison of recommendations for the first episode. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013881. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013881

14. Meltzer HY, Gadaleta E. Contrasting typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Focus. (2021) 19:3–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20200051

Keywords: cariprazine, full recovery, psychosis, neuroleptics, side effects, compliance, monotherapy

Citation: Taube M (2021) Case Report: Severe Side Effects Following Treatment With First Generation Antipsychotics While Cariprazine Leads to Full Recovery. Front. Psychiatry 12:804073. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.804073

Received: 28 October 2021; Accepted: 24 November 2021;

Published: 14 December 2021.

Edited by:

György Németh, Gedeon Richter, HungaryReviewed by:

Octavian Vasiliu, Dr. Carol Davila Central Military Emergency University Hospital, RomaniaMario Di Fiorino, Psychiatry of Versilia Hospital, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Taube. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maris Taube, bWFyaXMudGF1YmVAcnN1Lmx2

Maris Taube

Maris Taube