- 1The Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou Huiai Hospital), Guangzhou, China

- 2The First School of Clinical Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

Objectives: To first explore the role of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) concentrations in ketamine's antianhedonic effects, focusing on Chinese patients with treatment-refractory depression (TRD).

Methods: Seventy-eight patients with treatment-refractory major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder (BD) were treated with six ketamine infusions (0.5 mg/kg). Levels of anhedonia were measured using the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) anhedonia item at baseline, day 13 and 26. Plasma VEGF concentrations were examined at the same time points as the MADRS.

Results: Despite a significant reduction in anhedonia symptoms in individuals with treatment-refractory MDD (n = 59) or BD (n = 19) after they received repeated-dose ketamine infusions (p < 0.05), no significant changes in plasma VEGF concentrations were found at day 13 when compared to baseline (p > 0.05). The alteration of plasma VEGF concentrations did not differ between antianhedonic responders and non-responders at days 13 and 26 (all ps > 0.05). Additionally, no significant correlations were observed between the antianhedonic response to ketamine and plasma VEGF concentrations (all ps > 0.05).

Conclusion: This preliminary study suggests that the antianhedonic effects of ketamine are not mediated by VEGF.

Introduction

Anhedonia, a reduced capacity for pleasure, is regarded as one of the typical characteristics of major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar depression (BD) (1) and appears to occur irrespective of other depressive symptoms (2, 3). Anhedonia is a robust predictor of poor outcomes (4) and suicidal ideation independent of neurocognitive dysfunction and affective symptoms (5), suggesting that it appears to be an independent somatic domain in mood disorders (3). As a residual interepisodic symptom, anhedonia has been commonly described in patients suffering from treatment-refractory depression (TRD) treated with conventional pharmacotherapy (6). Patients with mood disorders, especially those with TRD, frequently endorse disturbance in reward capacity, providing the impetus for exploring novel agents and treatment approaches (7, 8).

Ketamine, as a dissociative anesthetic, is currently evaluated as a rapid-acting antidepressant. In addition to the rapid effect on depressive symptoms, ketamine also has rapid and robust effects on anhedonia symptoms (1, 9, 10) and suicidal ideation (11–13) in treatment-refractory BD and MDD. When compared with placebo, a single ketamine infusion could rapidly ameliorate anhedonia symptoms in individuals suffering from treatment-refractory BD; the reduction in anhedonia symptoms occurred within 40 min and lasted up to 14 days (10). Interestingly, ketamine's antianhedonic effects occur independently of the reduction in depressive symptoms (10).

Accumulating evidence has implicated neurotrophic factors including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (14–16) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (15–17) in the MDD and BD pathophysiology. VEGF can potentially mediate the antidepressant effects of ketamine (18, 19) and typical antidepressants (20). Similarly, serum BDNF levels were increased in chronic ketamine users (21) and change in plasma BDNF levels following subanesthetic ketamine infusion are associated with acute and 24 h resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) changes (22). Findings on the association of VEGF and ketamine's antidepressant effects have been inconsistent (18, 23–25). For example, the expression of VEGF is necessary for the antidepressant-like behaviors of ketamine (18, 19). A recent study supported a role for VEGF in the antidepressant action of ketamine (25), but two recent studies found that ketamine does not change the plasma concentrations of VEGF (23, 24). However, evidence on the role of plasma VEGF concentrations in ketamine's antianhedonic effects is still lacking.

Therefore, the main aim of this current study, which employed a real-world design, is to determine the role of plasma VEGF concentrations in the antianhedonic effects of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) administered thrice weekly over 2 weeks, focusing on Chinese subjects experiencing treatment-refractory MDD or BD.

Methods

Study Design and Population

Data were collected from an open-label, real-world ketamine clinical trial (registration number: ChiCTR-OOC-17012239). IRB approval of the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University was obtained for this study (Ethical Application Ref: 2016030). All participants gave written informed consent. In this study, we specifically report the relationship of plasma VEGF concentrations and antianhedonic effects of subanaesthetic doses of ketamine, focusing on individuals suffering from treatment-refractory MDD or BD. The detailed study design, study population and clinical findings of this single-center open-label ketamine clinical study were described in our early studies (26, 27). Briefly, seventy-eight subjects aged between 18 and 65 years were recruited, with a diagnosis of major depressive episode (MED)–MDD or BD–using DSM-5 criteria. In this study, each patient was required to score ≥ 17 points on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) (28, 29), experiencing TRD defined as failure to respond to at least two pharmacological therapies for the current MDE (30). Patients with other psychiatric disorders such as drug/alcohol dependence or schizophrenia were excluded, but a comorbidity of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) or anxiety disorder was permitted if it was not judged to be the primary presenting problem. Similar to prior studies (26, 27), each participant received six ketamine infusions (0.5 mg/kg over 40 min).

Antianhedonic Response

Similar to several early studies (31, 32), the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) anhedonia item including items 1 (apparent sadness), 2 (reported sadness), 6 (concentration difficulties), 7 (lassitude), and 8 (inability to feel) was also used in this study to assess anhedonia symptoms at baseline, day 13 and 26 (at the 1 day and 2 week follow-ups after completing the last infusion, respectively). Antianhedonic response was defined as at least a 50% reduction in MADRS anhedonia item scores on day 13.

Measurement of Plasma VEGF Concentrations

All blood samples of seventy-eight subjects with treatment-refractory MDD or BD were collected preinfusion and again at days 13 and 26. Consistent with a recent study (24), a Human VEGF Immunoassay enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) was used to measure the plasma concentrations of VEGF.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 24.0 statistical software focusing on Chinese patients suffering from treatment-refractory MDD or BD, with a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided). We performed a two-sample t-test and/or a Mann–Whitney U test as well as a chi-square test and/or a Fisher's exact test to compare the differences in baseline plasma concentrations of VEGF and demographic and clinical features between the two groups (patients with and without antianhedonic response), if necessary. A linear mixed model was conducted for changes in anhedonia symptoms as measured by MADRS and the plasma concentrations of VEGF over time between the two groups, with Bonferroni correction for the time points examined. Correlation analyses were conducted to determine the relationship of the effects of ketamine on anhedonia symptoms and the plasma concentrations of VEGF.

Results

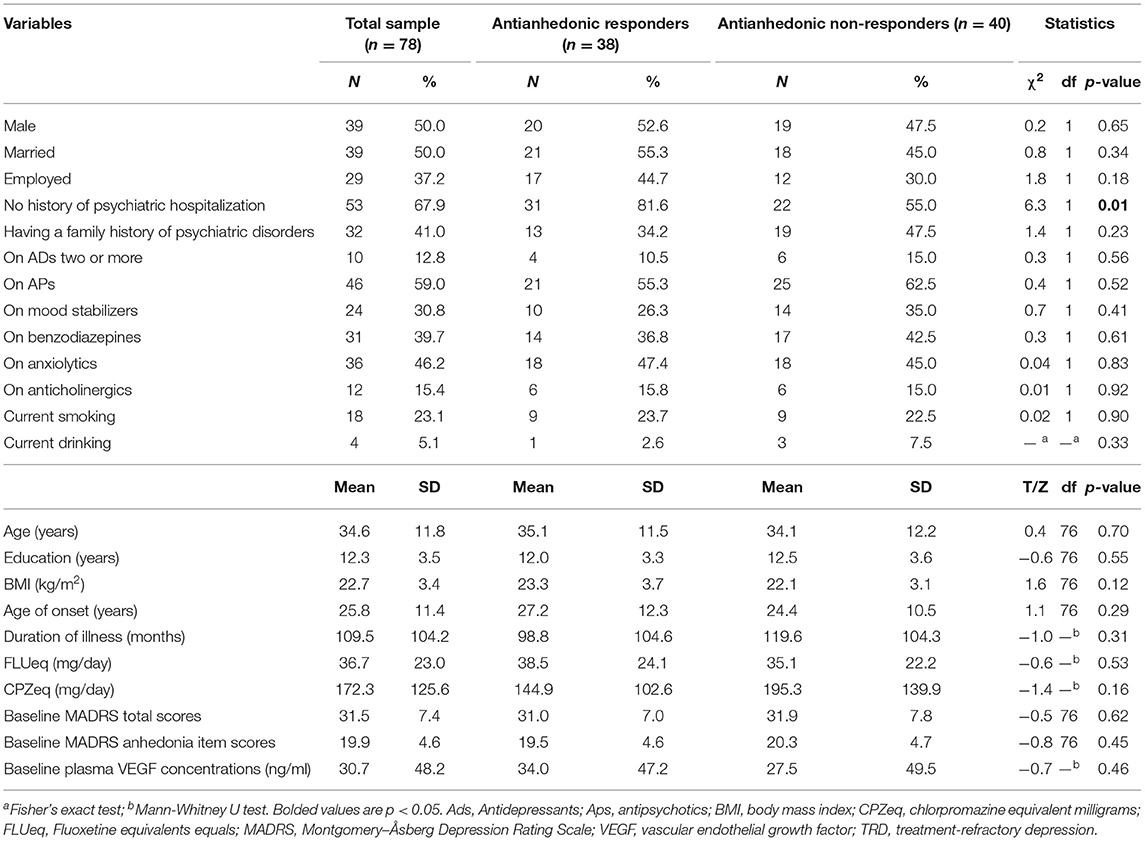

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical data of the patients suffering from treatment-refractory MDD (n = 59) or BD (n = 19) who received repeated ketamine infusions and provided a blood sample at baseline. Antianhedonic non-responders had a significantly higher history of psychiatric hospitalization than antianhedonic responders (p < 0.05).

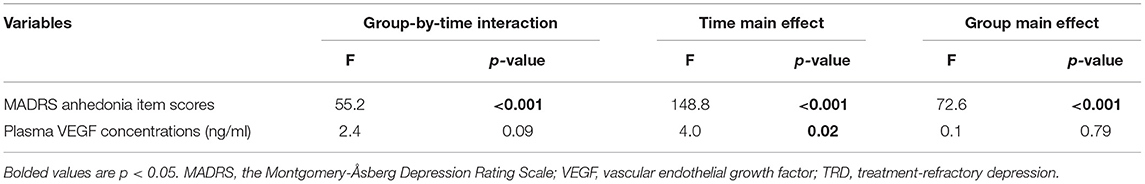

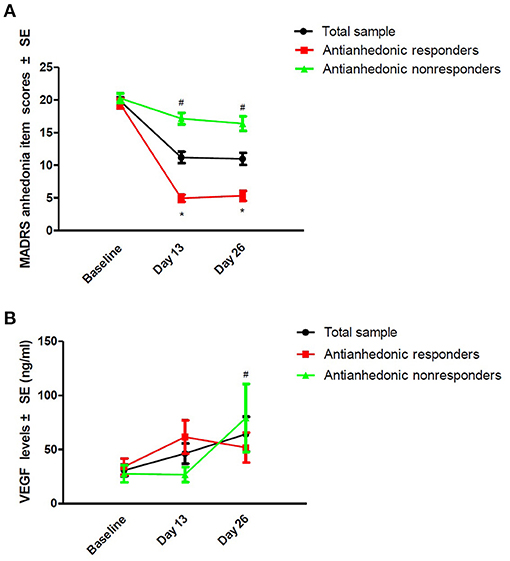

Thirty-eight patients (48.7%, 95% Cl = 37.4–60.1%) fulfilled the criteria for antianhedonic response. As depicted in Table 2, significant time main effects were found regarding MADRS anhedonia item scores and plasma VEGF concentrations (all ps < 0.05). No significant group main effects or group-by-time interactions were detected regarding plasma VEGF concentrations (all ps > 0.05; Table 2). Despite significant reductions in MADRS anhedonia item scores at days 13 and 26 (all ps < 0.05; Figure 1), no significant changes in plasma VEGF concentrations were observed at day 13 when compared to baseline (p > 0.05) (Figure 1). No significant differences in plasma VEGF concentrations were found between antianhedonic responders and non-responders at days 13 and 26 (all ps > 0.05) (Figure 1).

Table 2. Comparison of MADRS anhedonia item scores and plasma VEGF concentrations between antianhedonic responders and non-responders in subjects suffering from TRD using linear mixed models.

Figure 1. Change in anhedonia symptoms (A) and plasma VEGF concentrations (B) in subjects suffering from TRD. #Significant difference was found when compared to baseline at the indicated times (p < 0.05). *Significant difference was found between antianhedonic responders and non-responders at the indicated times (p < 0.05). MADRS, the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; SE, standard error; TRD, treatment-refractory depression; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

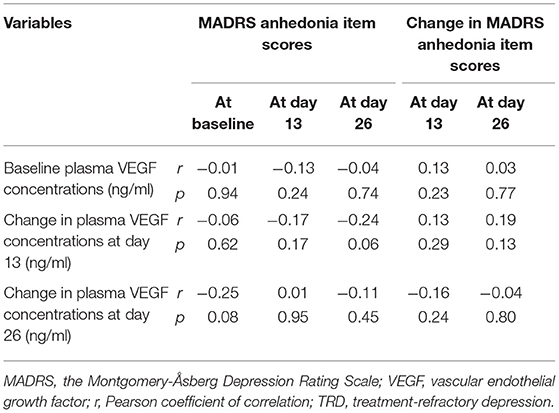

As shown in Table 3, correlation analysis of plasma VEGF concentrations and anhedonia symptoms as measured by the MADRS anhedonia item did not yield any significant relationships (all ps > 0.05).

Table 3. Relationship of baseline plasma VEGF concentrations and anhedonia symptoms in subjects suffering from TRD.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report to determine whether plasma VEGF concentrations are involved in the rapid antianhedonic effects of ketamine. The major finding in the present study was that (1) consistent with previous studies (1, 2, 9, 10), ketamine exerted significant and rapid antianhedonic effects; (2) plasma VEGF concentrations showed no significant changes at day 13, and no significant difference in plasma VEGF concentrations was found in antianhedonic responders compared to non-responders at days 13 and 26; and (3) plasma VEGF concentrations showed no significant correlation with the observed antianhedonic effects in individuals treated with six ketamine infusions.

In this study, the observed rapid reduction in anhedonia symptoms after six ketamine infusions replicates findings from numerous earlier studies (1, 2, 9, 10). Of them, the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) was used to evaluate the levels of anhedonia in some studies (1, 9, 10) but not all (2). In addition to the SHAPS, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) anhedonia item was used in Ballard et al. study (2). Similarly, a recent study examined the effects of esketamine on anhedonia symptoms by using MADRS item 8 (inability to feel) (30). In this study, the MADRS anhedonia item rather than a specific scale for anhedonia was used to evaluate anhedonia symptoms. Thus, a specific scale for anhedonia, such as the SHAPS and the Profile of Mood States (POMS), should be used to confirm these findings. Importantly, future studies should adopt a more specific assessment approach.

Preclinical trials have shown that rapid increases in VEGF in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) are required for the behavioral action of ketamine (33). Neuronal VEGF–Flk-1 signaling in the mPFC was associated with the antidepressant actions of ketamine (19). VEGF also appeared to be critical for the behavioral effects of various antidepressants (20, 34, 35) and lamotrigine (36) in rodent models of depression. In a recent clinical study, a single infusion of ketamine increased the plasma mRNA levels of VEGF, supporting a role for VEGF in the action of ketamine (25). However, our data failed to demonstrate that plasma VEGF concentrations were significantly associated with ketamine's rapid antianhedonic effects in subjects with TRD. Similarly, a recent study also found that VEGF does not play a critical role in the observed antidepressant response to ketamine in depressed patients (24). However, the association of VEGF and ketamine's antisuicidal effects is unclear.

There were several limitations in the current study. First, since patient samples were limited to Chinese subjects suffering from treatment-refractory MDD or BD, the findings may not be fully generalizable. In addition, the pooling of individuals diagnosed with MDD and BD made the sample nonhomogeneous. Second, patients continued receiving psychotropic medication in this open-label real-world study, which may have affected the plasma VEGF concentrations and partly explained the contradictory findings between our study and early reports (25). Third, we did not directly measure brain VEGF levels since blood VEGF levels may not be related to brain VEGF concentrations (37). Fourth, other key neurobiological mediators of the ketamine response, such as phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (p-GSK-3) or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (38, 39), should be measured in future studies. Finally, the possible comorbid diagnosis such as a comorbidity of OCD or anxiety disorder was not reported in this study. Although treatment strategies for OCD, substance use disorders (SUD) and eating disorders (ED) are complex and difficult, ketamine and esketamine appeared to be effective in treating them (40).

Conclusions

This preliminary study suggests that the antianhedonic effects of ketamine are not mediated by VEGF.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

YPN: study design. WZ, YLZ, and CYW: data collection. WZ and LMG: analysis and interpretation of data. WZ: drafting of the manuscript. BZ, DFW, and YPN: critical revision of the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the final draft of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82101609), Scientific Research Project of Guangzhou Bureau of Education (202032762), Science and Technology Program Project of Guangzhou (202102020658), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Liwan District of Guangzhou (202004034), Guangzhou Health Science and Technology Project (20211A011045), Guangzhou science and Technology Project of traditional Chinese Medicine and Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western medicine (20212A011018), China International Medical Exchange Foundation (Z-2018-35-2002), Guangzhou Clinical Characteristic Technology Project (2019TS67), Science and Technology Program Project of Guangzhou (202102020658), and Guangdong Hospital Association (2019ZD06). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rodrigues NB, McIntyre RS, Lipsitz O, Cha DS, Lee Y, Gill H, et al. Changes in symptoms of anhedonia in adults with major depressive or bipolar disorder receiving IV ketamine: results from the Canadian rapid treatment center of excellence. J Affect Disord. (2020) 276:570–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.083

2. Ballard ED, Wills K, Lally N, Richards EM, Luckenbaugh DA, Walls T, et al. Anhedonia as a clinical correlate of suicidal thoughts in clinical ketamine trials. J Affect Disord. (2017) 218:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.057

3. Słupski J, Cubała WJ, Górska N, Słupska A, Gałuszko-Wegielnik M. Copper and anti-anhedonic effect of ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. Med Hypotheses. (2020) 144:110268. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110268

4. Vrieze E, Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Hermans D, Pizzagalli DA, Sienaert P, et al. Dimensions in major depressive disorder and their relevance for treatment outcome. J Affect Disord. (2014) 155:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.020

5. Winer ES, Nadorff MR, Ellis TE, Allen JG, Herrera S, Salem T. Anhedonia predicts suicidal ideation in a large psychiatric inpatient sample. Psychiatry Res. (2014) 218:124–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.016

6. Cao B, Zhu J, Zuckerman H, Rosenblat JD, Brietzke E, Pan Z, et al. Pharmacological interventions targeting anhedonia in patients with major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 92:109–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.01.002

7. McCabe C, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ. Neural representation of reward in recovered depressed patients. Psychopharmacology. (2009) 205:667–77. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1573-9

8. Young CB, Chen T, Nusslock R, Keller J, Schatzberg AF, Menon V. Anhedonia and general distress show dissociable ventromedial prefrontal cortex connectivity in major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. (2016) 6:e810. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.80

9. Lally N, Nugent AC, Luckenbaugh DA, Niciu MJ, Roiser JP, Zarate CA. Neural correlates of change in major depressive disorder anhedonia following open-label ketamine. J Psychopharmacol. (2015) 29:596–607. doi: 10.1177/0269881114568041

10. Lally N, Nugent AC, Luckenbaugh DA, Ameli R, Roiser JP, Zarate CA. Anti-anhedonic effect of ketamine and its neural correlates in treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Transl Psychiatry. (2014) 4:e469. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.105

11. Witt K, Potts J, Hubers A, Grunebaum MF, Murrough JW, Loo C, et al. Ketamine for suicidal ideation in adults with psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of treatment trials. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2020) 54:29–45. doi: 10.1177/0004867419883341

12. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, Mathew SJ, Murrough JW, Feder A, et al. The Effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. (2018) 175:150–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040472

13. Zheng W, Zhou YL, Wang CY, Lan XF, Zhang B, Zhou SM, et al. Association between plasma levels of BDNF and the antisuicidal effects of repeated ketamine infusions in depression with suicidal ideation. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. (2020) 10:1–10. doi: 10.1177/2045125320973794

14. Caviedes A, Lafourcade C, Soto C, Wyneken U. BDNF/NF-κB signaling in the neurobiology of depression. Curr Pharm Des. (2017) 23:3154–63. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170111141915

15. Amidfar M, Réus GZ, de Moura AB, Quevedo J, Kim YK. The Role of neurotrophic factors in pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2021) 1305:257–72. doi: 10.1007/978-981-33-6044-0_14

16. Scola G, Andreazza AC. The role of neurotrophins in bipolar disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2015) 56:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.08.013

17. Tsai SJ, Hong CJ, Liou YJ, Chen TJ, Chen ML, Hou SJ, et al. Haplotype analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFA) gene and antidepressant treatment response in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. (2009) 169:113–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.028

18. Choi M, Lee SH, Chang HL, Son H. Hippocampal VEGF is necessary for antidepressant-like behaviors but not sufficient for antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2016) 1862:1247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.04.001

19. Deyama S, Bang E, Wohleb ES, Li XY, Kato T, Gerhard DM, et al. Role of neuronal VEGF signaling in the prefrontal cortex in the rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine. Am J Psychiatry. (2019) 176:388–400. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121368

20. Warner-Schmidt JL, Duman RS. VEGF is an essential mediator of the neurogenic and behavioral actions of antidepressants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2007) 104:4647–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610282104

21. Ricci V, Martinotti G, Gelfo F, Tonioni F, Caltagirone C, Bria P, et al. Chronic ketamine use increases serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Psychopharmacology. (2011) 215:143–8. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2121-3

22. Woelfer M, Li M, Colic L, Liebe T, Di X, Biswal B, et al. Ketamine-induced changes in plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels are associated with the resting-state functional connectivity of the prefrontal cortex. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2020) 21:696–710. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2019.1679391

23. Medeiros GC, Greenstein D, Kadriu B, Yuan P, Park LT, Gould TD, et al. Treatment of depression with ketamine does not change plasma levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor or vascular endothelial growth factor. J Affect Disord. (2021) 280:136–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.011

24. Zheng W, Zhou YL, Wang CY, Lan XF, Zhang B, Zhou SM, et al. Association of plasma VEGF levels and the antidepressant effects of ketamine in patients with depression. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. (2021) 11:1–7. doi: 10.1177/20451253211014320

25. McGrory CL, Ryan KM, Gallagher B, McLoughlin DM. Vascular endothelial growth factor and pigment epithelial-derived factor in the peripheral response to ketamine. J Affect Disord. (2020) 273:380–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.013

26. Zheng W, Zhou YL, Liu WJ, Wang CY, Zhan YN, Li HQ, et al. Rapid and longer-term antidepressant effects of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for patients with unipolar and bipolar depression. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) 106:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.09.013

27. Zheng W, Zhou YL, Liu WJ, Wang CY, Zhan YN, Li HQ, et al. Neurocognitive performance and repeated-dose intravenous ketamine in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. (2019) 246:241–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.005

28. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1960) 23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

29. Xie GR, Shen QJ. Use of the Chinese version of the hamilton rating scale for depression in general population and patients with major depression (In Chinese). Chin J Nerv Ment Dis. (1984) 10:364.

30. Delfino RS, Del-Porto JA, Surjan J, Magalhães E, Sant LCD, Lucchese AC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of esketamine in the treatment of anhedonia in bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. (2021) 278:515–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.056

31. McIntyre RS, Loft H, Christensen MC. Efficacy of vortioxetine on anhedonia: results from a pooled analysis of short-term studies in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2021) 17:575–85. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S296451

32. Cao B, Park C, Subramaniapillai M, Lee Y, Iacobucci M, Mansur RB, et al. The efficacy of vortioxetine on anhedonia in patients with major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00017

33. Deyama S, Bang E, Kato T, Li XY, Duman RS. Neurotrophic and antidepressant actions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor require vascular endothelial growth factor. Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 86:143–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.12.014

34. Greene J, Banasr M, Lee B, Warner-Schmidt J, Duman RS. Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling is required for the behavioral actions of antidepressant treatment: pharmacological and cellular characterization. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2009) 34:2459–68. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.68

35. Warner-Schmidt JL, Duman RS. VEGF as a potential target for therapeutic intervention in depression. Curr Opin Pharmacol. (2008) 8:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.013

36. Sun R, Li N, Li T. VEGF regulates antidepressant effects of lamotrigine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2012) 22:424–30. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.09.010

37. Levy MJF, Boulle F, Steinbusch HW, van den Hove DLA, Kenis G, Lanfumey L. Neurotrophic factors and neuroplasticity pathways in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. Psychopharmacology. (2018) 235:2195–220. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4950-4

38. Yang C, Zhou ZQ, Gao ZQ, Shi JY, Yang JJ. Acute increases in plasma mammalian target of rapamycin, glycogen synthase kinase-3β, and eukaryotic elongation factor 2 phosphorylation after ketamine treatment in three depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. (2013) 73:e35–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.022

39. Denk MC, Rewerts C, Holsboer F, Erhardt-Lehmann A, Turck CW. Monitoring ketamine treatment response in a depressed patient via peripheral mammalian target of rapamycin activation. Am J Psychiatry. (2011) 168:751–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010128

40. Martinotti G, Chiappini S, Pettorruso M, Mosca A, Miuli A, Di Carlo F, et al. Therapeutic potentials of ketamine and esketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), substance use disorders (SUD) and eating disorders (ED): a review of the current literature. Brain Sci. (2021) 11:856. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11070856

Keywords: ketamine, VEGF, antianhedonic effect, major depressive disorder, response

Citation: Zheng W, Gu LM, Zhou YL, Wang CY, Lan XF, Zhang B, Shi HS, Wang DF and Ning YP (2021) Association of VEGF With Antianhedonic Effects of Repeated-Dose Intravenous Ketamine in Treatment-Refractory Depression. Front. Psychiatry 12:780975. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.780975

Received: 22 September 2021; Accepted: 11 November 2021;

Published: 03 December 2021.

Edited by:

Celia J. A. Morgan, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Polymnia Georgiou, University of Maryland, Baltimore, United StatesGiovanni Martinotti, University of Studies G. d'Annunzio Chieti and Pescara, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Zheng, Gu, Zhou, Wang, Lan, Zhang, Shi, Wang and Ning. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu-Ping Ning, bmluZ2plbnlAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Wei Zheng

Wei Zheng Li-Mei Gu1

Li-Mei Gu1 Yan-Ling Zhou

Yan-Ling Zhou Bin Zhang

Bin Zhang Yu-Ping Ning

Yu-Ping Ning