95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 10 December 2021

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.777251

This article is part of the Research Topic The Consequences of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Students View all 71 articles

Jenney Zhu1,2

Jenney Zhu1,2 Nicole Racine1,2

Nicole Racine1,2 Elisabeth Bailin Xie1

Elisabeth Bailin Xie1 Julianna Park1

Julianna Park1 Julianna Watt1

Julianna Watt1 Rachel Eirich1,2

Rachel Eirich1,2 Keith Dobson1

Keith Dobson1 Sheri Madigan1,2*

Sheri Madigan1,2*The COVID-19 pandemic has posed notable challenges to post-secondary students, causing concern for their psychological well-being. In the face of school closures, academic disruptions, and constraints on social gatherings, it is crucial to understand the extent to which mental health among post-secondary students has been impacted in order to inform support implementation for this population. The present meta-analysis examines the global prevalence of clinically significant depression and anxiety among post-secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several moderator analyses were also performed to examine sources of variability in depression and anxiety prevalence rates. A systematic search was conducted across six databases on May 3, 2021, yielding a total of 176 studies (1,732,456 participants) which met inclusion criteria. Random-effects meta-analyses of 126 studies assessing depression symptoms and 144 studies assessing anxiety symptoms were conducted. The pooled prevalence estimates of clinically elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms for post-secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic was 30.6% (95% CI: 0.274, 0.340) and 28.2% (CI: 0.246, 0.321), respectively. The month of data collection and geographical region were determined to be significant moderators. However, student age, sex, type (i.e., healthcare student vs. non-healthcare student), and level of training (i.e., undergraduate, university or college generally; graduate, medical, post-doctorate, fellow, trainee), were not sources of variability in pooled rates of depression and anxiety symptoms during the pandemic. The current study indicates a call for continued access to mental health services to ensure post-secondary students receive adequate support during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Systematic Review Registration: PROSPERO website: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier: CRD42021253547.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted the lives of individuals around the world. Physical-distancing measures and quarantine orders implemented were intended to prepare for, and mitigate the risk of, an overburdened healthcare system. However, an unintended consequence of these protective measures is an increased risk for mental illness. Indeed, one of the largest and most sustained effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is estimated to be its negative effects on the mental health and well-being of citizens (1–4). Several emerging meta-analyses of general population samples show that rates of mental illness have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (1, 5). Further, large population-based samples with longitudinal pre-pandemic data have shown that the mental health of certain subgroups of the population have deteriorated more rapidly, including individuals aged 18–24 (3), many of whom are post-secondary students.

Post-secondary students may be uniquely at increased risk for mental illness during the pandemic due to university/college closures, academic disruptions, and social restrictions. Extensive research has been conducted on the mental health of post-secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic, and prevalence rates have varied widely, from 1.3–100% for clinically elevated depression and 1.1–100% for clinically elevated anxiety (6, 7). Ascertaining more precise estimates of clinically significant depression and anxiety symptoms among post-secondary students globally during the COVID-19 pandemic will be important for informing how supports can be allocated to young adults. To this end, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of research amassed to date. We also conducted demographic and methodological study quality moderator analyses in order to identify under what circumstances and for whom prevalence rates of depression and anxiety may be higher or lower. These moderator analyses may inform practice and health policy initiatives more reliably and be used to guide future research.

Depression and anxiety are two of the most common mental illnesses in the general population and represent leading causes of disease burden worldwide (8). Depression is characterized by overwhelming feelings of sadness, hopelessness, as well as lack of interest, pleasure, and/or motivation. Depression often has associated physical symptoms, such as sleep, appetite, and concentration difficulties. Anxiety includes symptoms such as excessive worry, physiological hyperarousal, and/or debilitating fear. Existing meta-analyses have demonstrated that, prior to COVID-19, 23.8% of Chinese university students and 24.4% of university students living in low- and middle-income countries experienced symptoms of depression (9, 10). Further, 33.8% of university students globally experienced at least mild symptoms of anxiety (11) and a meta-analysis of Iranian university students found 33% of students experienced mild to severe anxiety (12). A study of over 43,000 Canadian college students found 14.7 and 18.4% of students were diagnosed or treated for depression and anxiety, respectively, in the past 12 months (13).

There are several reasons to expect that depression and anxiety will rise due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Being quarantined is associated with negative psychological symptoms, such as stress, loneliness, confusion, and anger (14, 15). Fear of contamination, or fear of death to self or loved ones, can lead to efforts to increase self-isolation (16). The unpredictable and uncontrollable nature of COVID-19 can also increase mental distress. When social capital, such as social support, community integration, social norms, as well as family rituals, norms, and values are limited or inhibited, disruptions to emotional and behavioral regulation are likely to occur (16–18). Unique to post-secondary students, stressors include a fear of class cancellation and missed milestones (e.g., graduation), which could lead to increased psychological distress (19). Moreover, peer relationships represent a crucial and prominent source of social support among emerging adults (20). Given academic closures and isolation measures, students were distanced from a crucial support network during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To date, several meta-analyses have attempted to synthesize pooled prevalence estimates of depression and anxiety among post-secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research examining depression symptoms have found pooled prevalence rates that range from 26 to 34% (21–24) and anxiety symptoms that range from 28 to 31% (21, 24, 25). However, there are several limitations of the previous meta-analyses. First, their inclusion criteria often did not specify the need for moderate-to-severe symptoms, which are considered to indicate “clinically elevated” mental distress. Second, several of the meta-analyses examined specific student populations (e.g., nursing or medical students) who may experience higher rates of mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic due to stress from frontline clinical work (26) and may, in turn, inflate prevalence estimates. Third, several of the existing meta-analyses did not explore sources of between-study variability (i.e., moderators) in prevalence estimates. A central goal of a meta-analysis is to conduct moderator analyses to determine if between-study variability can be attributed to methodological or demographic factors. Finally, existing meta-analyses have only synthesized data from a portion of time over the course of the pandemic. The current meta-analysis addresses the above-mentioned issues by synthesizing data on clinically elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety (i.e., moderate to severe) which is more consistent with large-scale research reporting on the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders [e.g., (27)] and studies evaluating the global burden of diseases, which are typically based on the proportion of individuals who meet the threshold for DSM/ICD criteria (28). The present meta-analysis also addresses gaps in existing literature by conducting moderator analyses and includes studies on all populations of post-secondary students well over a year into the COVID-19 pandemic.

Within the context of a meta-analysis, moderator analyses can ascertain whether certain populations of post-secondary students are at higher risk for mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as whether certain study-level characteristics, such as methodological characteristics, explain variability in prevalence estimates. As mentioned, compared to studies investigating post-secondary students broadly, the mental health of students enrolled in healthcare fields involved in clinical work may have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 due to engaging in frontline clinical training in addition to the pandemic-related changes affecting all students, such as academic closures and online learning. Further, mental illness rates have been found to differ based on level of training. A previous meta-analysis found higher rates of mental illness among undergraduate students relative to graduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic (29). Differing rates of mental illness across levels of training could be the result of the distinct stressors at each level, which could be exacerbated by the pandemic. For example, undergraduate students are often adjusting to increased independence during an age that coincides with the onset of many mental illnesses (30). Graduate students, however, may be focused on academic work and have longer work hours which may limit the amount of time dedicated to protective factors such as social activities and hobbies (31). Another source of between-study variability could include methodological factors. For example, it is likely that the desire for rapid information about mental health during COVID-19 has led to less rigorous methodologies [e.g., convenience sampling; (32)], which may explain between-study heterogeneity. Geographical region may also increase or decrease the prevalence of mental illness during the pandemic. A meta-analysis of child and adolescent mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic found higher rates of anxiety symptoms in European countries compared to East Asian countries (4). Rates may vary across geographical region as certain countries or regions have more accepting attitudes toward mental illness (33). In addition, countries have varied in terms of COVID-19 infection rates, strictness of quarantine and self-isolation orders, and governmental responses to the pandemic, all of which could impact reports of mental distress. Rates may also vary over the course of the pandemic, such that continued social isolation and school disruptions may have more negative effects on mental health over time. Indeed, existing research has found that rates of mental illness were higher later in the pandemic compared to the beginning of the pandemic (4, 34). More generally, it is also well-established that symptoms of depression and anxiety are more common among females than males (33) and the age of onset for both depression and anxiety disorders begins in young adulthood (35), thus sex and age will also be examined as moderators.

The aim of the current meta-analysis was to provide estimates of the global prevalence of clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among post-secondary student samples. It was hypothesized that depression and anxiety have increased on account of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to prior global estimates. Methodological study quality, type of student (i.e., healthcare vs. non-healthcare), level of training (i.e., undergraduate, university or college generally; graduate, medical, post-doctorate, fellow, trainee), as well as participant sex, age, month data collection was completed, and geographical region were explored as potential moderating factors that may amplify or attenuate prevalence estimates.

This review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (36) and the PRISMA-S extension (37). The protocol for this review was developed by the authors and registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021253547). Searches were conducted in MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), APA PsycINFO (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Ovid), ERIC (EBSCOhost), and Education Research Complete (EBSCOhost) by a health sciences librarian on May 3, 2021. Search strategies combined search terms falling under three themes: (1) mental health and illness (including, anxiety and depression); (2) COVID-19; and (3) students (see Supplementary Tables 1–5 for full search strategies in each database). The search included students broadly with the understanding that results could be more deliberately limited to the post-secondary audience during the screening phase. Terms were searched both as keywords and as database subject headings as appropriate. Both adjacency operators and truncation were used to capture phrasing variations in keyword searching. No language or date restrictions were applied. References of relevant studies were reviewed manually for additional pertinent articles. Using Covidence software, three authors reviewed all titles, abstracts, and full text articles emerging from the search strategy to determine eligibility for inclusion. All abstracts were reviewed by at least two independent coders. Disagreements were resolved to consensus via expert review by the first author. All studies identified in the abstract review as meeting inclusion criteria, underwent full text review by five coders to ensure that all inclusion criteria were met. Thirty percent of full texts were reviewed by two independent coders and random agreement probabilities ranged from 0.72 to 0.90.

Studies meeting inclusion criteria during full text review underwent data extraction. In this phase, prevalence data on clinically elevated anxiety and depression symptoms were recorded. We also extracted data on the following moderators: (1) study quality (see below); (2) participant age (continuously as a mean); (3) sex (% male in a sample); (4) type of student (healthcare; non-healthcare); (5) level of training (undergraduate, university or college generally; graduate, medical, post-doctorate, fellow, trainee), (6) time of data collection (i.e., month in 2020) and (7) geographical region (e.g., East Asia, Europe, North America). Twenty percent of included studies underwent data extraction by a second coder to verify judgements for correctness and accuracy (random agreement probabilities ranged from 0.84 to 1.00). Discrepancies were resolved via discussion and attainment of consensus coding.

A 5-item study quality measure was used, based on modified versions of the National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observation Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (38) for cross-sectional studies (scores ranged from 0 to 5). The following criteria were applied: (1) outcome was assessed with a validated measure of depression and/or anxiety; (2) study was peer-reviewed vs. unpublished; (3) study had a response rate of at least 50%; (4) depression or anxiety was assessed objectively (i.e., diagnostic interview); (5) the study had sufficient exposure time to COVID-19 (i.e., at least 1 week since the onset of COVID-19 in the specific country where the study was conducted). Studies were given a score of 0 (no) or 1 (yes) for each criterion and a summed score out of 5. When information was not provided by the study authors, it was marked as 0 (no). The coding protocol for the quality scoring can be found in Supplementary Table 6.

Extracted data were entered into Comprehensive Meta-Analysis [CMA version 3.0; (39)]. Pooled prevalence rates were computed with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the estimate. CMA transforms the prevalence into a logit event rate (i.e., represented as 0.XX but interpreted as prevalence = XX%) with a computed standard error. Subsequently, event rates are weighted by the inverse of their variance, giving greater weight to studies with larger sample sizes. Finally, logits are retransformed into proportions to facilitate ease of interpretation.

Random-effects models, which assume that variations observed across studies exist because of differences in samples and study designs, were used. To assess for between-study heterogeneity, the Q and I2 statistics were computed. A significant Q statistic suggests that study variability is greater than sampling error and that moderator analyses should be explored (40). The I2 statistic, which ranges from 0 to 100%, examines the rate of variability across studies (41). Typically, when I2 values are > 75%, moderator analyses should be explored (41). As recommended by Borenstein et al. (39), categorical moderators were conducted when k ≥ 10 with a cell size of k > 3 for each categorical comparison. Random-effect meta-regression analyses were conducted with restricted maximum likelihood estimation for all continuous moderators. Egger's test and visual examination of funnel plots was utilized to identify publication bias (42). The set threshold for significance of moderators was p < 0.05.

As illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1), the electronic search yielded 3,614 records. After removing 1,207 duplicates, 548 full-text articles were retrieved for evaluation against inclusion criteria and 176 non-overlapping studies met full inclusion criteria.

The present meta-analysis included 176 studies, 126 of which reported clinically significant depression symptoms and 144 reported on clinically significant anxiety symptoms. As detailed in Table 1, across all 176 studies, 1,732,456 participants were included, with 35.6% being male and a mean age of 21.8 years (age range, 18.5–31.5). Forty-eight studies (27.3%) were from East Asia, 40 (22.7%) from Europe, 35 (19.9%) from South Asia, 18 (10.2%) from Middle East, 17 (9.7%) from North America, eight (4.5%) from Southeast Asia, four (2.3%) from Africa, three (1.7%) from Central America, one (0.6%) from Oceania, and two were from multiple geographical regions. The mean study quality score was 3.5 out of 5 (range: 2–4; see Supplementary Table 7). Specifically, 176 (100%) studies used validated measures; 176 (100%) were peer-reviewed, 102 (58.0%) had a response rate ≥ 50%, no studies (0%) used diagnostic interviews to assess clinically elevated anxiety or depression, and 165 (93.8%) of studies had sufficient exposure time to COVID-19.

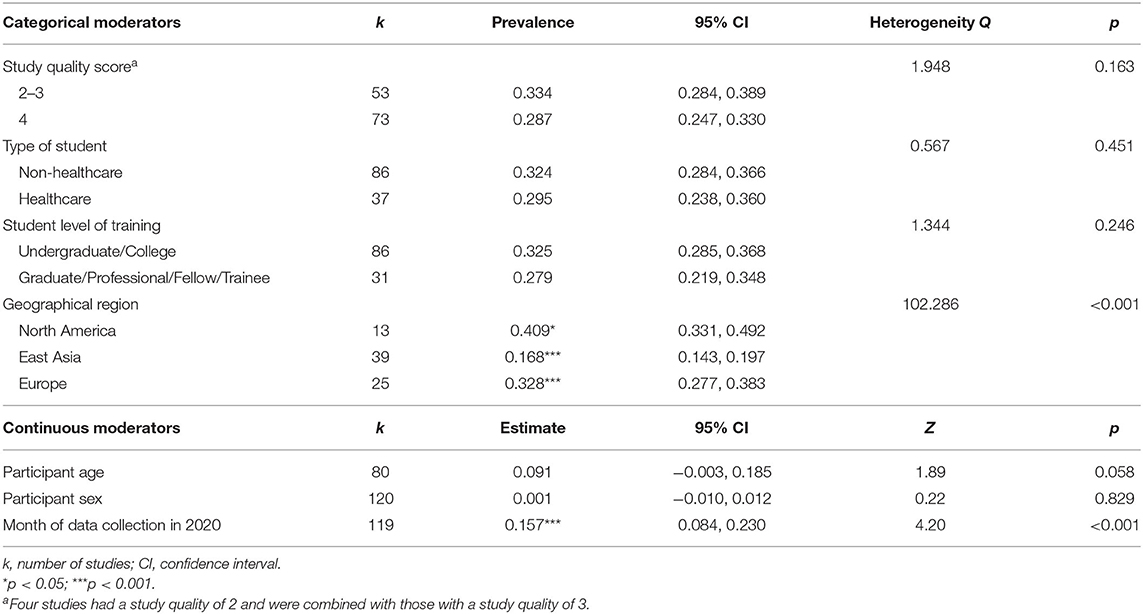

A random-effects meta-analysis of 126 studies revealed a pooled event rate of 0.306 (95% CI: 0.274, 0.340; see Figure 2). That is, the prevalence of clinically significant depression across studies was 30.6%. The funnel plot was symmetrical (see Supplementary Figure 1); however, Egger's test was significant (p = 0.028), indicating possible publication bias. There was significant between-study heterogeneity (Q = 128,577.686, p < 0.001, I2 = 99.90); thus, potential moderators were explored based on all included studies (see Table 2).

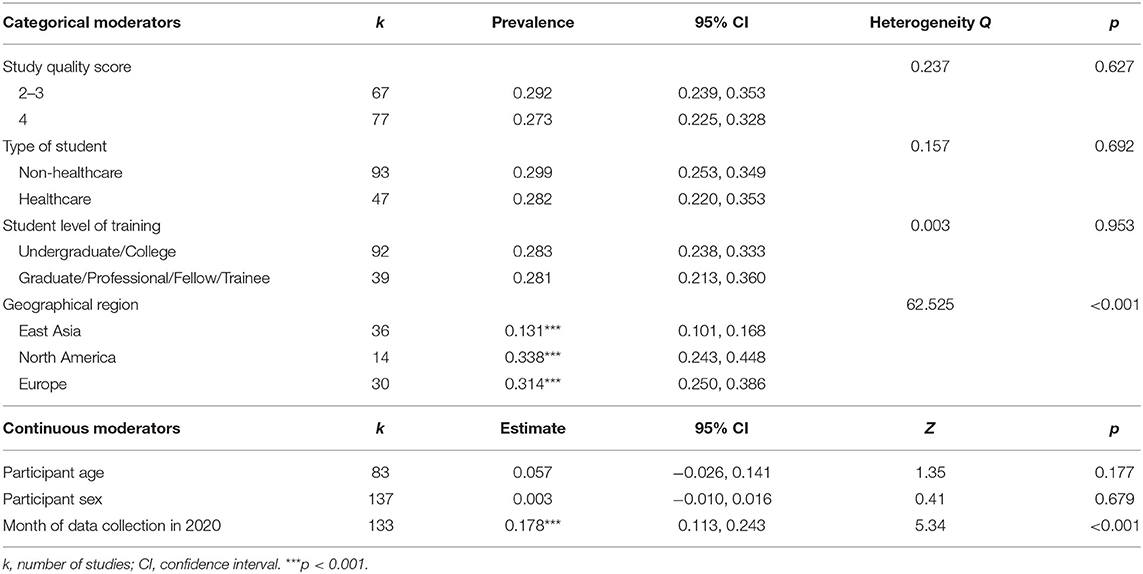

Table 2. Results of moderator analyses for the prevalence of depressive symptoms in post-secondary students during COVID-19.

Two moderators emerged as significant: geographical region and month of data collection. Specifically, prevalence of clinically significant depression was lower in studies conducted in East Asia (k = 39; rate = 0.168, 95% CI: 0.143, 0.197; p < 0.001) compared to studies from all other regions. The second significant moderator was month of data collection, such that for every 1-month increase, a 0.16% increase in depression prevalence was observed (k = 119; rate = 0.157, 95% CI: 0.084, 0.230; p < 0.001. None of age, sex, type of student, level of training, or study quality emerged as significant moderators for the prevalence of depression symptoms among students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

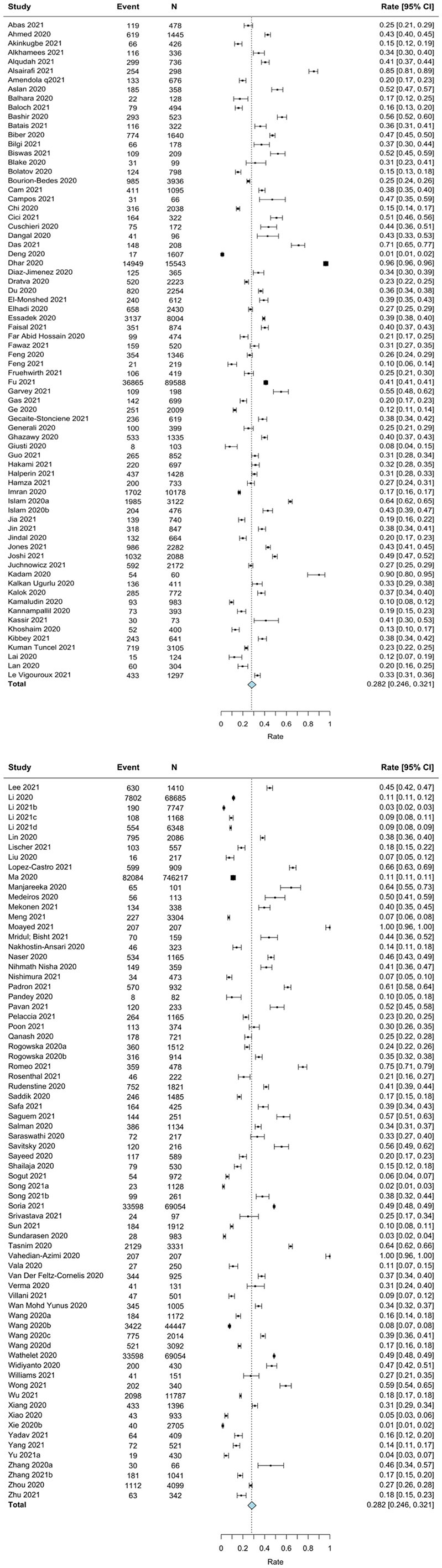

A random-effects meta-analysis of 144 studies revealed a pooled event rate of 0.282 (95% CI: 0.246, 0.321; Figure 3). That is, the prevalence of clinically significant anxiety across studies was 28.2%. The funnel plot was symmetrical (see Supplementary Figure 2); however, Egger's test was significant (p = 0.037), indicating possible publication bias. There was significant between-study heterogeneity with (Q = 160,472.80, p < 0.001, I2 = 99.91); thus, potential moderators were explored based on all included studies (see Table 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot for the meta-analysis on prevalence rates of anxiety in students during COVID-19.

Table 3. Results of moderator analyses for the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in post-secondary students during COVID-19.

Two moderators emerged as significant: geographical region and month of data collection. Specifically, the prevalence of clinically significant anxiety symptoms was lower among studies conducted in East Asia compared to all other geographical regions (k = 36; rate = 0.131, 95% CI: 0.101, 0.168; p < 0.001). Additionally, for every 1-month increase, a 0.18% increase in anxiety prevalence was observed (k = 133; rate = 0.178, 95% CI: 0.113, 0.243; p < 0.001). None of age, sex, type of student, level of training, or study quality emerged as significant moderators for the prevalence of clinically significant anxiety symptoms among students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the current meta-analysis, the pooled estimates of post-secondary students who reported clinically elevated depression (N = 126 studies) or anxiety (N = 144 studies) symptoms were 30.6 and 28.2%, respectively. Although findings of the present research indicate estimates are generally consistent with estimates prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which ranged from 23.8 to 33% (9, 10, 12), anxiety and depression among post-secondary students remains a cause for significant concern. First, the rates of clinically significant anxiety and depression observed among post-secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic were notably higher among students compared to the general population (216, 217) and continue to be higher relative to other populations during the COVID-19 pandemic [e.g., (4, 148)]. Second, in addition to the COVID-19 related stressors faced uniquely by student populations [e.g., academic disruptions and uncertainty; (19)], they also experienced many of the risk factors that have been attributed to worsened mental health among the general population, including financial insecurity, unemployment, and loss of loved ones (2). Indeed, post-secondary student populations lie at a unique intersection of elevated risk for mental health difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, results herein highlight the importance of continued investigation into who is struggling as well as which factors can be targeted through mental health intervention. For example, it will be important for future research to follow participants longitudinally to determine if current levels of anxiety and depression decrease, increase, and/or are sustained over time.

Although it may appear as though global estimates of mental health concerns in this population appear to have remained largely unchanged compared to pre-pandemic estimates, it is of utmost importance to consider the heterogeneous trajectories of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. That is, while the mental health of some students may have remained stable prior to, and during the pandemic, the pandemic may have initiated and/or attenuated mental distress in other students. Previous research has shown disparities in who was more severely impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic from a mental health standpoint (218). Recent studies showed that students who faced greater COVID-19 related stressors (e.g., lack of social support, uncertainties about academic programs) were more vulnerable to declines in mental health (122). Thus, whereas some students may have experienced consistent or improved mental health, it is likely that those with greater stressors may be disproportionately negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It will be important in future longitudinal research to examine the trajectories of mental distress from pre-pandemic to during the pandemic (and beyond) to ascertain a more complete picture of the patterns of stability and change in mental distress among post-secondary students.

We included a much larger sample of studies (n = 176, ~2 million participants) and applied more strict inclusion criteria in the current study, compared to previous meta-analyses. More specifically, we only included studies that reported clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms (i.e., above clinical cut-offs in the moderate to severe range), whereas previous meta-analyses have also included mild (i.e., subthreshold) symptoms in their pooled prevalence estimates, which could lead to estimate inflation. Nonetheless, the current prevalence estimates are in line with previous meta-analyses examining post-secondary student depressive [26–34%; (21–24)] and anxiety [28–31%; (21, 24, 25)] symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, unique to this meta-analysis was an examination of moderator variables. Results revealed that geographical location and month of data collection were important for explaining between-study differences in prevalence estimates, with rates of both anxiety and depression being lower in East Asian countries and higher as the month of data collection increased. Further, while estimates of mental illness typically vary by sex and age, these demographic factors did not explain between-study variability in the current meta-analysis of pandemic related mental illness symptoms, emphasizing the importance of providing adequate mental health services to individuals regardless of age or sex. As well, study quality was not a significant moderator. This may be related to the fact that there was limited variability in study quality among included studies (2–4 out of 5 with a mean study quality of 3.5). Although previous studies have found differences in student mental illness depending on level of study before (219) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (29), and healthcare fields may be disproportionately affected by the pandemic, none of these emerged as significant moderators. This finding may be explained by the fact that students working in healthcare fields may not necessarily be in direct contact with COVID-19 patients. Further, there may be stressors that negatively impact all students, regardless of level of training and type of student, such as financial stress.

This meta-analysis suggests that rates of clinically significant anxiety and depression among post-secondary students may be similar to pre-pandemic estimates. It is possible that the COVID-19 pandemic may have led to a shift in university and college procedures that created favorable learning conditions for post-secondary students. Take, for example, the finding that a sample of medical students reported lower levels of burnout during online learning over the course of the pandemic compared to traditional in-person learning pre-pandemic (85). As such, factors such as method of teaching delivery could have created an environment for students that decreases stress and increases flexibility and accessibility compared to in-person learning pre-pandemic.

Rates of anxiety and depression may also have remained relatively unchanged due to continued access to familial social support. Research during the pandemic has shown that college students who reported greater social support displayed better psychological health compared to those with lower levels of social support (122, 220). Many post-secondary students moved home and were in quarantine with family members. Returning home may have provided a source of support that helped to protect against the adverse mental health consequences of the pandemic, given that students who did not return to their home country or region reported more COVID-19 related stressors, including a lack of social support and worse mental health (122). For all students, access to social media may have been a particularly helpful tool to continue seeking and obtaining social support from peers, relatives, and colleagues (221).

Further, despite the disruption to mental health services during COVID-19 generally, many post-secondary students may have been able to continue to receive mental health services. Even prior to the pandemic, some colleges began implementing telehealth services to meet the increasing demands and these telemental health services may have been particularly helpful for students by allowing them to stay connected to care (222). Previous research has shown that many students, especially those with greater levels of depression and anxiety symptoms, are willing to use telemental health resources (223). Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of accessible mental health services and some institutions may be presently exploring strategies to promote better mental health among their students [e.g., (224, 225)].

Many included studies with the largest sample sizes were conducted in East Asian countries. The current results revealed that samples from East Asia possessed lower pooled prevalence rates of depression and anxiety compared to other geographical regions. Previous research has documented that East Asian populations may underreport or underestimate their psychological distress (32), either because they do not perceive their symptoms as indicative of mental health problems or due to the stigma associated with mental illness. Thus, the large representation of studies from East Asian countries should be considered in the interpretation of the minimal increase in results from pre- to during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, East Asian countries were also the first to report COVID-19 infections and had some of the strongest public health measures. The measures to “flatten the curve” may have reduced the risk of mental health responses where infection rates were diminished. These results are consistent with existing literature that similarly found rates of anxiety and depression among youth were lower in East Asian countries during COVID-19 (4). The current meta-analysis cannot explicate whether regional differences in the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms were related to true cultural differences in these symptoms, or to differing attitudes and reports of symptoms.

In addition to geographical region, the current study revealed month of data collection as a moderator of elevated depression and anxiety, such that rates of depression and anxiety increased later into the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding parallels a recent meta-analysis on children and adolescents (4), which also found that mental health deteriorated over the course of the pandemic. Among young adults, peer relationships can be an important element of social support (20). Although students may have experienced increased familial support throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, campus closures and social distancing measures removed students from a critical source of social support (i.e., peers). One possible explanation for the current finding is that social isolation, campus closures, and academic disruptions had a compounding effect on the mental health of post-secondary students as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed (14, 19). Alternatively, studies conducted earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to have been conducted in East Asia as East Asian countries were the first to report COVID-19 infections (Racine et al., 2021). Previous studies have indicated that self-reported prevalence of psychological distress tends to be lower among East Asian populations (226).

The results of this meta-analysis should be viewed within the context of several limitations. First, power was limited in some categorical moderator analyses due to small sample sizes at each level of the moderator variable. Several potentially interesting moderators could also not be explored as there were insufficient studies reporting on these factors. For example, factors that may have increased or decreased prevalence rates of anxiety and depression could include SES, history of pre-existing mental disorder, and living situation (e.g., subjected to stay-at-home vs. physical distancing orders). Indeed, pandemic-related mental health research has shown that mental illness tends to increase during periods of quarantine and self-isolation. A fuller exploration of these factors in future research will be essential for planning and targeting interventions to address mental distress. Relatedly, despite strict criteria for inclusion in the present meta-analysis (e.g., use of clinical cut off scores for depression and anxiety), there was still considerable heterogeneity among the included studies that was not accounted for by the tested moderators. This indicates there is notable heterogeneity in research conducted on this topic to date, suggesting there may be unexplored moderators that further account for the observed heterogeneity. Future research may wish to explore moderators including SES, vaccination rates, and mental health assessment measures to determine if greater heterogeneity among existing research can be accounted for. Second, while all included studies used validated measures of anxiety and depressive symptoms, no study to date has employed diagnostic measures. Therefore, our results are based on elevated self-reports of moderate to severe anxiety and depressive symptoms, but not diagnoses of these disorders. Fourth, all included studies are cross-sectional reports of mental illness symptoms. Cross-sectional studies can establish rates of mental illness during an acute period of distress, but it is critical to establish if the estimated prevalence rates are sustained over time.

This meta-analysis provided a synthesis of existing evidence on clinically elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms experienced by post-secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research should attend to several methodological issues to inform this body of research more fully and to increase the applicability of findings for health policy and practice (32, 227). First, as aptly outlined by others (2, 32), more rigorous recruitment methods, such as random sampling methods, are critical in order to fully understand the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic and capture inequalities experienced by vulnerable groups. Second, it is important for future research to continue to longitudinally examine whether the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms remain constant, decrease, or increase over the course of the pandemic, and beyond. For example, an innovative study by Ayers et al. (228) demonstrated that internet searches for acute anxiety spiked early in the pandemic compared to historical pre-pandemic levels, but following the peak of the pandemic, searches returned to historical pre-pandemic levels. To date, several longitudinal studies have been conducted to assess mental illness throughout the COVID-19 pandemic [e.g., (3, 229, 230)]. For example, emerging longitudinal research on student populations by Amendola et al. (50) shows that the prevalence of moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic decreased between the first to second timepoint. As highlighted above, the present research underscores the need for additional longitudinal research on mental illness among post-secondary student populations over the course of, and in the aftermath of, the COVID-19 pandemic to determine if estimates are sustained over time and/or lead to an increase in treatment seeking. Cohort samples with baseline estimates pre-COVID-19 pandemic are particularly advantageous, as they can ascertain changes in prevalence rates on account of the COVID-19 pandemic. Future longitudinal studies can also be harnessed to examine mechanisms associated with mental health, so that targets of interventions can be mechanistically informed (2).

Future research should explore additional contextual factors that may impact the risk for mental illness. For example, student SES may have notable impacts on the ability to engage in online learning. Consider the fact that stable internet connection, electronic devices, and a workspace at home are all prerequisites to partaking in online learning. Indeed, high SES has been found to be a protective factor following natural disasters and low SES students tended to report higher rates of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic (231, 232). Examination of such factors may inform how best to support students and gain a better understanding regarding how to target prevention and intervention efforts. Further, targeted research with post-secondary students who have pre-existing mental illness and may be particularly impacted by COVID-related stressors [e.g., loss of social capital, suspension of mental health services; (233)] is critical to determine if these stressors have exacerbated mental illness or increased the potential for relapse (16). Initial research has found that female university students with pre-existing mental illness reported greater loneliness, avoidant, and negative emotional coping during the pandemic compared to those without pre-existing mental illness (234). Finally, to our knowledge, few studies have examined protective factors that may mitigate the risk for mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sun et al. (181) found that, among a sample of university students, perceived social support and mindfulness was associated with lower anxiety and depression symptoms. It will be important to conduct additional research to examine whether the protective benefits of social support differ between physical and virtual social support, for example, and can buffer the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, to further inform policy and resource planning.

The current results implicate a need for continued, and possibly increased, availability of mental health services to meet the needs of students who develop or continue to experience pre-existing mental health symptomatology during, and following, the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research has shown that unaddressed mental health difficulties can lead to poor long-term health (235), as well as lost income and productivity (236). Distress and anxiety related to unemployment or fear of contracting illness may be best addressed via broader social or public health interventions, rather than psychiatric care. Thus, governments and policymakers must prioritize the funding and provision of mental health services alongside social and public health interventions that broadly improve quality of life.

Mental health supports for post-secondary students are of utmost importance given the high rates of clinically significant anxiety and depression both prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, it may be necessary to provide students with psychoeducational materials regarding mental health and well-being (i.e., importance of sleep hygiene, routines, exercise) and create increased accessibility to in-person and/or telemental health services. Telemental health services in particular will be important to increase equitable accessibility and improve scalability for student populations (237). Further, academic accommodations, including flexible deadlines and the option of virtual lectures, for students suffering from severe mental distress should be implemented in post-secondary institutions. The mental health needs of some students may surpass what can be provided by on-campus mental health centers, and funding for students to access mental health services in the community may be necessary. Given that stress is a primary precipitant of mental illness (238), policies that reduce stress by offering students financial support (i.e., income supplements) and social support (e.g., peer support resources; helplines) may be necessary and represent important mental health prevention efforts (239). Overall, these suggestions are encouraged both during, and following, the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, while the implementation of quarantine may be necessary at times, previous research suggests that quarantine is associated with psychological distress (14), and as such, the closure of post-secondary institutions should be considered a last resort.

The current meta-analysis of 176 studies and close to 2 million participants demonstrate consistent prevalence rates of clinically elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms prior to, and during, the COVID-19 pandemic among post-secondary students. The COVID-19 pandemic represents a global crisis, both with respect to its physical consequences, but also its dire implications for the mental health of individuals globally. As such, the results of the current study represent a clarion call for urgent and sustained funding and support for evidence-based mental health screening, case-finding, and treatment for depression and anxiety.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

NR, SM, and JZ: concept and design. JZ, NR, RE, KD, and SM: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. NR: statistical analysis. SM: administrative, technical, and material support. NR and SM: supervision. All authors: acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors acknowledge Nicole Dunnewold, MLIS (University of Calgary), for conducting the literature search for this project.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.777251/full#supplementary-material

1. Cooke JE, Eirich R, Racine N, Madigan S. Prevalence of posttraumatic and general psychological stress during COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2020). 292:113347. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113347

2. Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020). 7:547–60. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

3. Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020). 2020:ssrn.3624264. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3624264

4. Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc Pediatr. (2021). 2021:2482. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

5. Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Niu J, Yin X, Xie J, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2021). 281:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117

6. *Deng C-H, Wang J-Q, Zhu L-M, Liu H-W, Guo Y, Peng X-H, et al. Association of web-based physical education with mental health of college students in Wuhan during the COVID-19 outbreak: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. (2020). 22:e21301. doi: 10.2196/21301

7. *Vahedian-Azimi A, Moayed MS, Rahimibashar F, Shojaei S, Ashtari S, Pourhoseingholi MA. Comparison of the severity of psychological distress among four groups of an Iranian population regarding COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. (2020). 20:402. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02804-9

8. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1994). 51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002

9. Akhtar P, Ma L, Waqas A, Naveed S, Li Y, Rahman A, et al. Prevalence of depression among university students in low and middle income countries (LMICs): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2020). 274:911–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.183

10. Lei X-Y, Xiao L-M, Liu Y-N, Li Y-M. Prevalence of depression among Chinese University Students: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2016). 11:e0153454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153454

11. Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res. (2012). 47:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015

12. Sarokhani D, Delpisheh A, Veisani Y, Sarokhani MT, Esmaeli Manesh R, Sayehmiri K. Prevalence of depression among university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Depress Res Treat. (2013). 2013:373857–373857. doi: 10.1155/2013/373857

13. Esmaeelzadeh S, Moraros J, Thorpe L, Bird Y. The association between depression, anxiety and substance use among Canadian post-secondary students. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2018). 14:3241. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S187419

14. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. (2020). 395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

15. Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2013). 7:105–10. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22

16. Asmundson GJG, Paluszek MM, Landry CA, Rachor GS, McKay D, Taylor S. Do pre-existing anxiety-related and mood disorders differentially impact COVID-19 stress responses and coping? J Anxiety Disord. (2020). 102271. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102271

17. Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Lim JX, Ho M-hR, Rohde P. Incidence, recurrence and comorbidity of anxiety disorders in four major developmental stages. J Affect Disord. (2018). 228:248–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.014

18. Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). outbreak in January 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit Int Med J Exp Clin Res. (2020). 26:e923921. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923921

19. Hasan N, Bao Y. Impact of “e-Learning crack-up” perception on psychological distress among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: a mediating role of “fear of academic year loss” Children and Youth Services. Review. (2020). 118:105355. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105355

20. Lee CY, Goldstein SE. Loneliness. Stress, and social support in young adulthood: does the source of support matter? J Youth Adolesc. (2016). 45:568–80. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9

21. Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, Silver Z, Wong CY, Chang O, et al. The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2021). 301:113863–113863. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113863

22. Guo S, Kaminga AC, Xiong J. Depression and coping styles of college students in China during COVID-19 pandemic: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. (2021). 9:735. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.613321

23. Luo W, Zhong BL, Chiu HFK. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2021). 2021:1–50. doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000202

24. Chang J, Ji Y, Li Y, Pan H, Su P. Prevalence of anxiety symptom and depressive symptom among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2021). 292:242–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.109

25. Lasheras I, Gracia-García P, Lipnicki DM, Bueno-Notivol J, López-Antón R, De La Cámara C, et al. Prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020). 17:6603. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186603

26. Guerrini Christi J, Storch Eric A, McGuire Amy L. Essential, not peripheral: addressing health care workers' mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Occup Health. (2020). 62:e12169. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12169

27. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen H-U. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2012). 21:169–84. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

28. Baxter AJ, Vos T, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Whiteford HA. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol Med. (2014). 44:2363–74. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713003243

29. Chirikov I, Soria KM, Horgos B, Jones-White D. Undergraduate and Graduate Students' Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. SERU Consortium (2020).

30. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005). 62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

31. Wyatt T, Oswalt SB. Comparing mental health issues among undergraduate and graduate students. Am J Health Educ. (2013) 44:96–107. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2013.764248

32. Pierce M, McManus S, Jessop C, John A, Hotopf M, Ford T, et al. Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020). 7:567–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20).30237-6

33. James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. (2018). 392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18).32279-7

34. Tomfohr-Madsen LM, Racine N, Giesbrecht GF, Lebel C, Madigan S. Depression and anxiety in pregnancy during COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2021). 113912. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113912

35. Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso Caballero J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2007). 20:359–64. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c

36. Page MJ, Moher D, McKenzie JE. Introduction to PRISMA 2020 and implications for research synthesis methodologists. Res Synthesis Methods. (2021). doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1535

37. Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:39. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z

38. Wells G. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analysis. (2004). Available online at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology.oxford.htm (accessed September 1, 2021).

39. Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3. Englewood, NJ: Biostat (2013).

40. Borenstein M, Hesdges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. West Sussex: Wiley. (2009). doi: 10.1002/9780470743386

41. Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analysis. Br Medican J. (2003). 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

42. Egger M, Davey G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997). 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

43. *Abas IMY, Alejail IIEM, Ali SM. Anxiety among the Sudanese university students during the initial stage of COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon. (2021). 7:e06300. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06300

44. *Ahmed M, Hamid R, Hussain G, Bux M, Ahmed N, Kumar M. Anxiety and depression in medical students of Sindh province during the covid-19 pandemic. Rawal Med J. (2020). 45:947–50. Available online at: https://www.rmj.org.pk/index.php?fulltxt=123902&fulltxtj=27&fulltxtp=27-1597076831.pdf (accessed September 1, 2021).

45. *Akinkugbe AA, Garcia DT, Smith CS, Brickhouse TH, Mosavel M. A descriptive pilot study of the immediate impacts of COVID-19 on dental and dental hygiene students' readiness and wellness. J Dent Educ. (2021). 85:401–10. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12456

46. *Alkhamees AA, Aljohani MS. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the students of Saudi Arabia. Open Public Health J. (2021). 14:12–23. doi: 10.2174/1874944502114010012

47. *Alqudah A, Al-Smadi A, Oqal M, Qnais EY, Wedyan M, Abu Gneam M, et al. About anxiety levels and anti-anxiety drugs among quarantined undergraduate Jordanian students during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Clin Practic. (2021). 2021:e14249. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14249

48. *Alsairafi Z, Naser AY, Alsaleh FM, Awad A, Jalal Z. Mental health status of healthcare professionals and students of health sciences faculties in Kuwait during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021). 18:42203. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042203

49. *Amatori S, Donati Zeppa S, Preti A, Gervasi M, Gobbi E, Ferrini F, et al. Dietary habits and psychological states during COVID-19 home isolation in Italian College Students: the role of physical exercise. Nutrients. (2020). 12:12366.0 doi: 10.3390/nu12123660

50. *Amendola S, von Wyl A, Volken T, Zysset A, Huber M, Dratva J. A longitudinal study on generalized anxiety among university students during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Switzerland. Front Psychol. (2021). 12:643171. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643171

51. *Amerio A, Brambilla A, Morganti A, Aguglia A, Bianchi D, Santi F, et al. COVID-19 Lockdown: housing built environment's effects on mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020). 17:65973. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165973

52. *Aslan I, Ochnik D, Cinar O. Exploring perceived stress among students in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020). 17:238961. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17238961

53. Aylie NS, Mekonen MA, Mekuria RM. The psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic among university students in Bench-Sheko Zone, South-west Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manage. (2020) 13:813–21. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S275593

54. *Balhara YPS, Kattula D, Singh S, Chukkali S, Bhargava R. Impact of lockdown following COVID-19 on the gaming behavior of college students. Indian J Public Health. (2020). 64:S172–6. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_465_20

55. *Baloch GM, Sundarasen S, Chinna K, Nurunnabi M, Kamaludin K, Khoshaim HB, et al. COVID-19: exploring impacts of the pandemic and lockdown on mental health of Pakistani students. PeerJ. (2021). 9:e10612. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10612

56. *Bashir TF, Hassan S, Maqsood A, Khan ZA, Issrani R, Ahmed N, et al. The psychological impact analysis of novel COVID-19 pandemic in health sciences students: a global survey. Eur J Dentistry. (2020). 14:S91–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721653

57. *Batais MA, Temsah M-H, AlGhofili H, AlRuwayshid N, Alsohime F, Almigbal TH, et al. The coronavirus disease of 2019 pandemic-associated stress among medical students in middle east respiratory syndrome-CoV endemic area: an observational study. Medicine. (2021). 100:e23690. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023690

58. *Biber DD, Melton B, Czech DR. The impact of COVID-19 on college anxiety, optimism, gratitude, and course satisfaction. J Am College Health. (2020). 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1842424

59. *Bilgi K, Aytas G, Karatoprak U, Kazancioglu R, Ozcelik S. The effects of coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak on medical students. Front Psychiatry. (2021). 12:637946. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.637946

60. *Biswas S, Biswas A. Anxiety level among students of different college and universities in India during lock down in connection to the COVID-19 pandemic. Zeitschrift fur Gesundheitswissenschaften. (2021). 8:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01431-8

61. *Blake H, Corner J, Cirelli C, Hassard J, Briggs L, Daly JM, et al. Perceptions and experiences of the university of nottingham pilot SARS-CoV-2 asymptomatic testing service: a mixed-methods study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020). 18:10188. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010188

62. *Bolatov AK, Seisembekov TZ, Askarova AZ, Baikanova RK, Smailova DS, Fabbro E. Online-learning due to COVID-19 improved mental health among medical students. Med Sci Educator. (2020). 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01165-y

63. *Bourion-Bedes S, Tarquinio C, Batt M, Tarquinio P, Lebreuilly R, Sorsana C, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on students in a French region severely affected by the disease: results of the PIMS-CoV 19 study. Psychiatry Res. (2021). 295:113559. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113559

64. *Brett W, King C, Shannon B, Gosling C. Impact of COVID-19 on paramedicine students: a mixed methods study. Int Emerg Nurs. (2021). 56:100996. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2021.100996

65. *Cam HH, Ustuner Top F, Kuzlu Ayyildiz T. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and health-related quality of life among university students in Turkey. Curr Psychol. (2021). 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01674-y

66. *Campos JADB, Campos LA, Bueno JL, Martins BG. Emotions and mood swings of pharmacy students in the context of the coronavirus disease of 2019 pandemic. Curr Pharmacy Teach Learn. (2021). 13:635–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2021.01.034

67. *Chakraborty T, Subbiah GK, Damade Y. Psychological distress during COVID-19 lockdown among dental students and practitioners in India: a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Dentistry. (2020). 14:S70–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1719211

68. *Chen RN, Liang SW, Peng Y, Li XG, Chen JB, Tang SY, et al. Mental health status and change in living rhythms among college students in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: a large-scale survey. J Psychosomatic Res. (2020). 137:110219. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110219

69. *Chi X, Becker B, Yu Q, Willeit P, Jiao C, Huang L, et al. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of mental health outcomes among chinese college students during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). pandemic. Front Psychiatry. (2020). 11:803. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00803

70. *Cici R, Yilmazel G. Determination of anxiety levels and perspectives on the nursing profession among candidate nurses with relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2021). 57:358–62. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12601

71. *Cuschieri S, Calleja Agius J. Spotlight on the shift to remote anatomical teaching during covid-19 pandemic: perspectives and experiences from the University of Malta. Anat Sci Educ. (2020). 13:671–9. doi: 10.1002/ase.2020

72. *Dangal MR, Bajracharya LS. Students anxiety experiences during COVID-19 in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. (2021). 18:53–7. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v18i2.32957

73. *Das R, Hasan MR, Daria S, Islam MR. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among general Bangladeshi population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2021). 11:e045727. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045727

74. *Dhar BK, Ayittey FK, Sarkar SM. Impact of COVID-19 on psychology among the university students. Glob Challenges. (2020). 2020:2000038. doi: 10.1002/gch2.202000038

75. *Diaz-Jimenez RMPD, Caravaca-Sanchez FPD, Martin-Cano MCPD, De la Fuente-Robles YMPD. Anxiety levels among social work students during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Social Work Health Care. (2020). 59:681–93. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2020.1859044

76. *Dratva J, Zysset A, Schlatter N, von Wyl A, Huber M, Volken T. Swiss university students' risk perception and general anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020). 17:207433. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207433

77. *Du C, Zan MCH, Cho MJ, Fenton JI, Hsiao PY, Hsiao R, et al. Increased resilience weakens the relationship between perceived stress and anxiety on sleep quality: a moderated mediation analysis of higher education students from 7 countries. Clocks Sleep. (2020). 2:334–53. doi: 10.3390/clockssleep2030025

78. Dun Y, Ripley-Gonzalez JW, Zhou N, Li Q, Chen M, Hu Z, et al. The association between prior physical fitness and depression in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—a cross-sectional, retrospective study. Peer J. (2021) 9:e11091. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11091

79. *Elhadi M, Buzreg A, Bouhuwaish A, Khaled A, Alhadi A, Msherghi A, et al. Psychological impact of the civil war and COVID-19 on libyan medical students: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. (2020). 11:570435. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570435

80. *El-Monshed AH, El-Adl AA, Ali AS, Loutfy A. University students under lockdown, the psychosocial effects and coping strategies during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional study in Egypt. J Am College Health. (2021). 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1891086

81. *Essadek A, Rabeyron T. Mental health of French students during the Covid-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. (2020). 277:392–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.042

82. *Evans S, Alkan E, Bhangoo JK, Tenenbaum H, Ng-Knight T. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample. Psychiatry Res. (2021). 298:113819. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113819

83. *Faisal RA, Jobe MC, Ahmed O, Sharker T. Mental health status, anxiety, and depression levels of Bangladeshi university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Mental Health Addict. (2021). 2021:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00458-y

84. *Far Abid Hossain S, Nurunnabi M, Sundarasen S, Chinna K, Kamaludin K, Baloch GM, et al. Socio-psychological impact on Bangladeshi students during COVID-19. J Public health Res. (2020). 9:1911. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2020.1911

85. *Fawaz M, Samaha A. E-learning: depression, anxiety, and stress symptomatology among Lebanese university students during COVID-19 quarantine. Nurs For. (2021). 56:52–7. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12521

86. *Feng Y, Zong M, Yang Z, Gu W, Dong D, Qiao Z. When altruists cannot help: the influence of altruism on the mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Health. (2020). 16:61. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00587-y

87. *Feng S, Zhang Q, Ho SMY. Fear and anxiety about COVID-19 among local and overseas Chinese university students. Health Soc Care Commun. (2021). 2021:hsc.13347. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13347

88. *Fruehwirth JC, Biswas S, Perreira KM. The Covid-19 pandemic and mental health of first-year college students: examining the effect of Covid-19 stressors using longitudinal data. PLoS ONE. (2021). 16:e0247999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247999

89. *Fu W, Yan S, Zong Q, Anderson-Luxford D, Song X, Lv Z, et al. Mental health of college students during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. J Affect Disord. (2021). 280:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.032

90. *Garvey AM, Garcia IJ, Otal Franco SH, Fernandez CM. The psychological impact of strict and prolonged confinement on business students during the COVID-19 pandemic at a Spanish University. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021). 18:41710. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041710

91. *Gas S, Eksi Ozsoy H, Cesur Aydin K. The association between sleep quality, depression, anxiety and stress levels, and temporomandibular joint disorders among Turkish dental students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cranio J Craniomandibular Practice. (2021). 2021:1–6. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2021.1883364

92. *Ge F, Zhang D, Wu L, Mu H. Predicting psychological state among chinese undergraduate students in the COVID-19 epidemic: a longitudinal study using a machine learning. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2020). 16:2111–8. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S262004

93. *Gecaite-Stonciene J, Saudargiene A, Pranckeviciene A, Liaugaudaite V, Griskova-Bulanova I, Simkute D, et al. Impulsivity mediates associations between problematic internet use, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in students: a cross-sectional COVID-19 study. Front Psychiatry. (2021). 12:634464. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.634464

94. *Generali L, Iani C, Macaluso GM, Montebugnoli L, Siciliani G, Consolo U. The perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental undergraduate students in the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna. Eur J Dental Educ. (2020). 2020:eje.12640. doi: 10.1111/eje.12640

95. *Ghazawy ER, Ewis AA, Mahfouz EM, Khalil DM, Arafa A, Mohammed Z, et al. Psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on the university students in Egypt. Health Promot Int. (2020). 2020:daaa147. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaa147

96. *Giusti L, Salza A, Mammarella S, Bianco D, Ussorio D, Casacchia M, et al. Everything will be fine. Duration of home confinement and “all-or-nothing” cognitive thinking style as predictors of traumatic distress in young university students on a digital platform during the COVID-19 Italian lockdown. Front Psychiatry. (2020). 11:574812. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.574812

97. *Graupensperger S, Benson AJ, Kilmer JR, Evans MB. Social (un).distancing: teammate interactions, athletic identity, and mental health of student-athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. (2020). 67:662–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.001

98. *Guo AA, Crum MA, Fowler LA. Assessing the psychological impacts of COVID-19 in undergraduate medical students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021). 18:62952. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062952

99. *Hakami Z, Khanagar SB, Vishwanathaiah S, Hakami A, Bokhari AM, Jabali AH, et al. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). pandemic on dental students: a nationwide study. J Dent Educ. (2021). 85:494–503. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12470

100. *Halperin SJ, Henderson MN, Prenner S, Grauer JN. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical students during the covid-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Med Educ Curr Dev. (2021). 8:2382120521991150. doi: 10.1177/2382120521991150

101. *Hamza CA, Ewing L, Heath NL, Goldstein AL. When social isolation is nothing new: a longitudinal study on psychological distress during COVID-19 among university students with and without preexisting mental health concerns. Can Psychol. (2021). 62:20–30. doi: 10.1037/cap0000255

102. *Imran N, Masood HMU, Ayub M, Gondal KM. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on postgraduate trainees: a cross-sectional survey. Postgraduate Med J. (2020). 97:632–7. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138364

103. *Islam MA, Barna SD, Raihan H, Khan MNA, Hossain MT. Depression and anxiety among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: a web-based cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE. (2020). 15:e0238162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238162

104. *Islam MS, Sujan MSH, Tasnim R, Sikder MT, Potenza MN, van Os J. Psychological responses during the COVID-19 outbreak among university students in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. (2020). 15:e0245083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245083

105. *Jia Y, Qi Y, Bai L, Han Y, Xie Z, Ge J. Knowledge-attitude-practice and psychological status of college students during the early stage of COVID-19 outbreak in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2021). 11:e045034. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045034

106. *Jin L, Hao Z, Huang J, Akram HR, Saeed MF, Ma H. Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with problematic smartphone use under the COVID-19 epidemic: the mediation models. Child Youth Services Rev. (2021). 121:105875. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105875

107. *Jindal V, Mittal S, Kaur T, Bansal AS, Kaur P, Kaur G, et al. Knowledge, anxiety and the use of hydroxychloroquine prophylaxis among health care students and professionals regarding COVID-19 pandemic. Adv Respirat Med. (2020). 88:520–30. doi: 10.5603/ARM.a2020.0163

108. *Jones HE, Manze M, Ngo V, Lamberson P, Freudenberg N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college students' health and financial stability in New York City: findings from a population-based sample of City University of New York (CUNY). students. J Urban Health. (2021). 98:187–96. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00506-x

109. *Joshi A, Kaushik V, Vats N, Kour S. Covid-19 pandemic: pathological, socioeconomical and psychological impact on life, and possibilities of treatment. Int J Pharmaceut Res. (2021). 13:2724–38. doi: 10.31838/ijpr/2021.13.02.361

110. *Juchnowicz D, Baj J, Forma A, Karakula K, Sitarz E, Bogucki J, et al. The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the well-being of polish students: the risk factors of the emotional distress during COVID-19 lockdown. J Clin Med. (2021). 10:50944. doi: 10.3390/jcm10050944

111. *Kadam P, Jabade M, Ligade T. A study to assess the student's anxiety level about examination during lock down in selected colleges of pune city. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. (2020). 14:3723–5. doi: 10.37506/ijfmt.v14i4.12211

112. *Kalkan Ugurlu Y, Durgun H, Gok Ugur H, Mataraci Degirmenci D. The examination of the relationship between nursing students' depression, anxiety and stress levels and restrictive, emotional, and external eating behaviors in COVID-19 social isolation process. Perspectiv Psychiatric Care. (2020). 57:507–16. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12703

113. *Kalok A, Sharip S, Abdul Hafizz AM, Zainuddin ZM, Shafiee MN. The psychological impact of movement restriction during the COVID-19 outbreak on clinical undergraduates: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020). 17:228522. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228522

114. *Kamaludin K, Chinna K, Sundarasen S, Khoshaim HB, Nurunnabi M, Baloch GM, et al. Coping with COVID-19 and movement control order (MCO).: experiences of university students in Malaysia. Heliyon. (2020). 6:e05339. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05339

115. *Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, McAlister RP, Duncan J. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS ONE. (2020). 15:e0237301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237301

116. *Kaparounaki CK, Patsali ME, Mousa DPV, Papadopoulou EVK, Papadopoulou KKK, Fountoulakis KN. University students' mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Res. (2020). 290:113111. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111

117. *Kassir G, El Hayek S, Zalzale H, Orsolini L, Bizri M. Psychological distress experienced by self-quarantined undergraduate university students in Lebanon during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Psychiatry Clin Practice. (2021). 2021:1900872. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2021.1900872

118. *Khoshaim HB, Al-Sukayt A, Chinna K, Nurunnabi M, Sundarasen S, Kamaludin K, et al. Anxiety level of university students during COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. Front Psychiatry. (2020). 11:579750. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579750

119. *Kibbey MM, Fedorenko EJ, Farris SG. Anxiety, depression, and health anxiety in undergraduate students living in initial US outbreak “hotspot” during COVID-19 pandemic. Cogn Behav Therapy. (2021). 2020:1853805. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2020.1853805

120. *Kohls E, Baldofski S, Moeller R, Klemm S-L, Rummel-Kluge C. Mental health, social and emotional well-being, and perceived burdens of university students during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Germany. Front Psychiatry. (2021). 12:643957. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643957

121. *Kuman Tuncel O, Tasbakan SE, Gokengin D, Erdem HA, Yamazhan T, Sipahi OR, et al. The deep impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: an online cross-sectional study evaluating Turkish students' anxiety. Int J Clin Practice. (2021). 2021:e14139. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14139

122. *Lai AY-K, Lee L, Wang M-P, Feng Y, Lai TT-K, Ho L-M, et al. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on international university students, related stressors, and coping strategies. Front Psychiatry. (2020). 11:584240. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.584240

123. *Lan HT. Q., Long NT, Hanh NV. Validation of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21).: immediate psychological responses of students in the E-learning environment. Int J Higher Educ. (2020). 9:125–33. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v9n5p125

124. *Le Vigouroux S, Goncalves A, Charbonnier E. The psychological vulnerability of french university students to the COVID-19 confinement. Health Educ Behav. (2021). 48:123–31. doi: 10.1177/1090198120987128

125. *Lee J, Jeong HJ, Kim S. Stress, anxiety, and depression among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic and their use of mental health services. Innov Higher Educ. (2021). 21:9552. doi: 10.1007/s10755-021-09552-y

126. *Li D, Zou L, Zhang Z, Zhang P, Zhang J, Fu W, et al. The psychological effect of COVID-19 on home-quarantined nursing students in China. Front Psychiatry. (2021). 12:652296. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.652296

127. *Li X, Lv Q, Tang W, Deng W, Zhao L, Meng Y, et al. Psychological stresses among Chinese university students during the COVID-19 epidemic: the effect of early life adversity on emotional distress. J Affect Disord. (2021). 282:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.126

128. *Li Y, Qin L, Shi Y, Han J. The psychological symptoms of college student in China during the lockdown of COVID-19 epidemic. Healthcare. (2021). 9:40447. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9040447

129. *Li Y, Zhao J, Ma Z, McReynolds LS, Lin D, Chen Z, et al. Mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: a 2-wave longitudinal survey. J Affect Disord. (2021). 281:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.109

130. *Liang S-W, Chen R-N, Liu L-L, Li X-G, Chen J-B, Tang S-Y, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on Guangdong College Students: the difference between seeking and not seeking psychological help. Front Psychol. (2020). 11:2231. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02231

131. *Lin J, Guo T, Becker B, Yu Q, Chen S-T, Brendon S, et al. Depression is associated with moderate-intensity physical activity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: differs by activity level, gender and gender role. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2020). 13:1123–34. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S277435

132. *Lin Y, Hu Z, Alias H, Wong LP. Influence of mass and social media on psychobehavioral responses among medical students during the downward trend of COVID-19 in Fujian, China: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. (2020). 22:e19982. doi: 10.2196/19982

133. *Lischer S, Safi N, Dickson C. Remote learning and students' mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: a mixed-method enquiry. Prospects. (2021). 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09530-w

134. *Liu J, Zhu Q, Fan W, Makamure J, Zheng C, Wang J. Online mental health survey in a medical college in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychiatry. (2020). 11:459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00459

135. *Lopez-Castro T, Brandt L, Anthonipillai NJ, Espinosa A, Melara R. Experiences, impacts and mental health functioning during a COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown: data from a diverse New York City sample of college students. PLoS ONE. (2021). 16:e0249768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249768

136. *Ma Z, Zhao J, Li Y, Chen D, Wang T, Zhang Z, et al. Mental health problems and correlates among 746 217 college students during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2020). 29:e181. doi: 10.1017/S2045796020000931

137. *Majumdar P, Biswas A, Sahu S. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: cause of sleep disruption, depression, somatic pain, and increased screen exposure of office workers and students of India. Chronobiol Int. (2020). 37:1191–200. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1786107

138. *Manjareeka M, Pathak M. COVID-19 lockdown anxieties: is student a vulnerable group? J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Mental Health. (2020). 17:72–80. Available online at: https://jiacam.org/ojs/index.php/JIACAM/article/download/644/352 (accessed September 1, 2021).

139. *Mechili EA, Saliaj A, Kamberi F, Girvalaki C, Peto E, Patelarou AE, et al. Is the mental health of young students and their family members affected during the quarantine period? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic in Albania. J Psychiatric Mental Health Nurs. (2020). 2020:jpm.12672. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12672

140. *Medeiros RAD, Vieira DL, Silva EVFD, Rezende LVMDL, Santos RWD, Tabata LF. Prevalence of symptoms of temporomandibular disorders, oral behaviors, anxiety, and depression in Dentistry students during the period of social isolation due to COVID-19. J Appl Oral Sci. (2020). 28:e20200445. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2020-0445

141. *Mekonen EG, Workneh BS, Ali MS, Muluneh NY. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on graduating class students at the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2021). 14:109–22. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S300262

142. *Meng N, Liu Z, Wang Y, Feng Y, Liu Q, Huang J, et al. Beyond sociodemographic and COVID-19-related factors: the association between the need for psychological and information support from school and anxiety and depression. Med Sci Monitor. (2021). 27:e929280. doi: 10.12659/MSM.929280

143. *Miskulin FPC, Da Silva TCRP, Pereira MB, Neves BA, Almeida BC, Perissotto T, et al. P.700 Prevalence of depression in medical students during lockdown in Brazil due to COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2020). 40(Suppl.1).:S399. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.09.518

144. *Moayed MS, Vahedian-Azimi A, Mirmomeni G, Rahimi-Bashar F, Goharimoghadam K, Pourhoseingholi MA, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19).-associated psychological distress among medical students in Iran. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2021). 1321:245–51. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-59261-5_21

145. *Mridul B. B., Sharma D, Kaur N. Online classes during covid-19 pandemic: anxiety, stress & depression among university students. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. (2021). 15:186–9. doi: 10.37506/ijfmt.v15i1.13394

146. *Mushquash AR, Grassia E. Coping during COVID-19: examining student stress and depressive symptoms. J Am College Health. (2021). 2020:1865379. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1865379