94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Psychiatry, 12 November 2021

Sec. Aging Psychiatry

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.774533

This article is part of the Research TopicInsights in Aging Psychiatry: 2021View all 12 articles

With a steady increase in population aging, the proportion of older people living with mental illness is on rise. This has a significant impact on their autonomy, rights, quality of life and functionality. The biomedical approach to mental healthcare has undergone a paradigm shift over the recent years to become more inclusive and rights-based. Dignity comprises of independence, social inclusion, justice, equality, respect and recognition of one's identity. It has both subjective and objective components and influences life-satisfaction, treatment response as well as compliance. The multi-dimensional framework of dignity forms the central anchor to person-centered mental healthcare for older adults. Mental health professionals are uniquely positioned to incorporate the strategies to promote dignity in their clinical care and research as well as advocate for related social/health policies based on a human rights approach. However, notwithstanding the growing body of research on the neurobiology of aging and old age mental health disorders, dignity-based mental healthcare is considered to be an abstract and hypothetical identity, often neglected in clinical practice. In this paper, we highlight the various components of dignity in older people, the impact of ageism and mental health interventions based on dignity, rights, respect, and equality (including dignity therapy). It hopes to serve as a framework for clinicians to incorporate dignity as a principle in mental health service delivery and research related to older people.

The world's population is aging rapidly with persons aged 65 or older projected to reach 1.5 billion by 2050 (1). Approximately 20% of them will have mental health conditions such as dementia, depression, anxiety and substance use, often complicated by physical and psychosocial comorbidities (2). Implicit and explicit biases that negatively influence their care include the triple jeopardy of ageism, mentalism, and ableism (3). The concept of dignity is complex and forms the ethical basis for enhancing a person's sense of wellbeing and quality of life, especially for persons with mental health conditions. Our neurobiological understanding of late-life mental health conditions has improved significantly over the last few decades, but there is an urgent and significant unmet need to incorporate the principles of dignity within mental health service delivery (4). This is particularly important to address for clinicians caring for older persons who must respect the human rights and the autonomy of every person. Incorporating dignity in the care of older persons takes on greater importance, due to their multiple and interdependent vulnerabilities such as physical, psychological, cognitive, and social frailty, interacts with dependence on others, loneliness, social isolation, polypharmacy, medical comorbidities subjecting them to human rights abuses, loss of autonomy and poorer access to healthcare. Promoting their dignity and protecting older persons against stigma, discrimination, violence, abuse and neglect enhances clinical outcomes and quality of life.

Practical models for promoting the principles of dignity, and a rights-based approach to mental health care, serve as a moral, ethical, and legal anchor to support the independence and autonomy of older persons with mental health conditions (5–7). Most older persons have higher ratings of successful aging despite declining physical and cognitive function and satisfied with their quality of life (8), however with speedy population aging, there are several others with increased needs of support. These include people with chronic medical illnesses, geriatric depression and anxiety, as well as neurocognitive disorders. Besides functional recovery, optimum management of their conditions also needs to preserve their independence, respect, autonomy and rights. Even though most of these concepts are of a Western origin, transcultural connotations are common. This assumes a special significance in light of the United Nations Convention for Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD), which views human rights as an “instrument with an explicit, social development dimension” (9). There are currently 82 signatories to the Convention who agree that fundamental freedoms should be at the core of healthcare in conditions of disability, which include psychiatric disorders. The UNCRPD changes the approach from viewing the “mentally disabled” as “subjects of charity needing medical and social protection” to “individuals with human rights who can participate in society and informed decision-making with appropriate care” (10). This furthers the concept the autonomy and free will beyond the geographical and cultural boundaries. Besides, autonomy in a mental health setting, but also in other contexts of vulnerability, is often an ideal that can become a fallacy if structural factors are ignored; in some settings, the ideal of autonomy should be framed as interdependency (11–13). Controversies about the cultural acceptability of the concept of “autonomy” aside, it is only one of the dimensions of dignity, which is a much more holistic concept in healthcare. The social context of care, process of caregiving, challenges associated with aging and psychiatric symptoms: all can be potentially grounded in recognition of the individual's abilities, respecting the free will, preventing health inequalities and recognition of diversities, all of which constitute dignified mental healthcare in daily practice (14). As global health inequalities are widening, more so in light of the ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, incorporating dignity in mental health services and planning become more important. Non-inclusion of such practices in mental health policies and programmes have led to poor healthcare access, stigma, inadequate social welfare benefits and discrimination in older people (15, 16).

Dignity is a complex multi-dimensional construct with a high likelihood for various subjective interpretations. It is difficult to have an universally agreed definition for such an abstract concept. Nevertheless, people are usually able to recognize when an individual's dignity is violated, and also when dignity in care is enhanced. Hence, when we talk about the need for dignity in mental health, there needs to be a shared understanding among clinicians, patients, caregivers and policy-makers alike (14, 17).

Dignity has often been conceptualized in sync of human rights in being of “value or worthy” and enjoying the “deserved respect.” The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act toward one another in a spirit of brotherhood” (18). This is translated in the Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO) when it is stated that “The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of age, race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition” (19).

In the practice of medicine, dignity gradually became a focus for physicians and medical researchers. In more recent debates, it has been invoked in questions of bioethics of human genetic engineering, human cloning, and end-of-life care (20). In June 1964, the World Medical Association issued the Declaration of Helsinki that says at article 11: “It is the duty of physicians who participate in medical research to protect the life, health, dignity, integrity, right to self-determination, privacy, and confidentiality of personal information of research subjects” (21). The Council of Europe, on 4th April 1997, at Oviedo, approved the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine. The Convention states that “Parties to this Convention shall protect the dignity and identity of all human beings and guarantee everyone, without discrimination, respect for their integrity and other rights and fundamental freedoms with regard to the application of biology and medicine” (22).

A phenomenological analysis of how care providers perceived dignity as a core value in healthcare promotion in older people revealed that it was constituted by three primary components: worthiness, autonomy, and identity (23). The authors state that these themes reflected the principles of nursing practice to improve the older patient's health potential. Ivbijaro et al. (24) highlighted that dignity is not simply a medical strategy but rather a holistic outlook to healthcare which involves both service users and providers. They mention cultural sensitivity, kindness, respect, empathy, independence, autonomy and self-esteem as the various dimensions of dignified mental healthcare for older people. Targeting these attributes in various settings through collaborative care can enhance the quality of life of seniors who are mentally ill. Further, principles of dignity can also help counteract ageist attitudes, negative beliefs and social stereotypes about “being old” both among the general public and mental healthcare professionals (25). It's also vital how service consumers understand dignity themselves. A recent meta-synthesis explored the “understandings of dignity” from the perspective of older adults in the Nordic countries (26). The need for recognition and visibility formed the overarching theme and also an important unmet need in healthcare. There was a critical need to balance between “toning down their illness to gain more independence” vs. “losing a voice by being less visible to the society.” Hence, besides autonomy and independence, the need for social visibility also formed a vital component of dignity. In lines with the same, mental health first aid delivery based on dignity has shown to be an effective public health intervention tool for improving knowledge, attitude and practices (27). Informed decision-making, participation in healthcare, providing audience to the voices of persons with mental illness and a non-judgemental approach formed the main components.

Based on this evidence, personal dignity can be understood in two interconnected ways: internal (how I see myself) and external (how others see me) (28). Each is dependent on the other. Hence, as a mental health professional it is essential to have an inclusive, empathetic and non-discriminative approach to consider the individual as “an independent human being” rather than just a “subject of care.” This brings in the sense of “subjectiveness” and “individualism” which are important constructs of self-dignity (26). The temptation to stereotype older adults into a single homogenous group takes away their individuality, contributes to the increased stigma associated with older age and increases the risk of denying them their dignity. Based on ethical principles, dignity has also been conceptualized as autonomy/self-determination, non-maleficence, ensuring justice, and veracity (right to know and participate in their treatment process) (20).

It is clear from the discussion above that dignity involves various attributes which reinforce each other. Also the perceptions vary based on needs and care-providing. Unfortunately, most of the interventions and guidelines speak about “needs and should” in dignified mental healthcare rather than highlighting the processes of change (28, 29). Dignity in true sense is both structural and interpersonal. These dynamics need to be considered while imbibing it into mental health interventions. A common fallacy is attributing lack of dignity solely to psychological causes while it is divorced from “symptoms” which essentially have a medical model. This dichotomy is potentially harmful (30). It is high time that the premise of dignity and rights in mental healthcare of older adults are considered through a biopsychosocial model. Maintaining respect, optimum medication to ensure functional independence and granting social recognition as an individual go hand-in-hand and hence no single dimension of personal dignity can exist in a vacuum. As Clancy et al. (26) state that the effect of mental illness is to make older people invisible to the society and their voices unheard, it is the onus of healthcare providers to protect them from this “cloak of invisibility.”

Collaborative care is the cornerstone of mental health services in older people. This requires both empathy and community support. There is growing evidence that clinical empathy–the medical professional's cognitive understanding of the emotions of people with mental illness combined with emotional attachment–directly enhances therapeutic efficacy (31). Increasingly, training in empathetic behavior must be a priority among healthcare professionals caring for the elderly (32). While delivering mental health services for older people, it is important to consider the social determinants of health, which are dynamic throughout the life-course, especially in later life. Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age and which are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels (33). These undergo complex interaction with genetic factors, personal experiences as well as the social environment to influence psychological wellbeing. The various dimensions involved in mental illness that also influences personal dignity and human rights in older people are depicted in Figure 1.

Social determinants may play a role as risk factors for mental health problems (unemployment, poverty, inequalities, stigma and discrimination, poor housing, adverse childhood experiences, violence, abuse, drug and alcohol abuse, poor general health, caring duties), while others may be protective factors (social protection, resilience, social networks, positive community engagement, positive spiritual life, hope, optimism, good general health, good quality family interactions, positive intergenerational relationships) (34, 35).

By acting on social determinants of health, it is possible to contribute to promote the older adults' dignity and a better subjective mental health and well-being of older people, to build the capacity of communities to manage adversity, and to reduce the burden and consequences of mental health problems. Disadvantages because of mental health problems in old age damage the social cohesion of communities and societies by decreasing interpersonal trust, social participation and civic engagement (36). The present-day nosology-focused symptom-triggered psychiatric care often aim at relieving the signs of illness and reduce hospitalization. This can at times deprive the voices of the service-users with their exclusion from the management plan. According to Minoletti (37)

“dignity for persons with mental disorders is exercising citizenship, with a sense of empowerment and control over their lives, and demanding the same rights (e.g., the right to decide where to live, whom to meet, whom to love, where to work, etc.) and take the same responsibilities (e.g., respecting the laws, voting, volunteering, paying taxes, etc.) as other citizens.”

Hence, besides symptom resolution, enjoying citizenship, feeling respected (as well as self-respected), honored, and inclusive are vital components of care in a mentally ill older adult. This makes the resultant mental healthcare for older adults comprehensive and patient-centered rather than bureaucratic and directive.

Ageism manifests in various forms throughout the life course and is most impactful in old age. It is the stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination against an individual based on his/her age or the aging process (38). Coined in 1969 by Robert Butler, it primarily denotes ageist attitudes against senior citizens, although it is also rooted in sexism and racism (38). The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Report on Ageism was developed by the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs as well as the United Nations Population Fund (UNPF) (39). The report calls upon healthcare policies, intergenerational and multi-disciplinary interventions to combat ageist behavior against older people, considering ageism as a major barrier to personal dignity and social visibility (39). Ageism is widespread across places providing health and social care, in workplace, the media, etc. to an extent nearly 50% of the global population have some or the other variation of ageist thoughts, which is much more prevalent in the low-and-middle-income countries (40). Ageism has shown to compound the stigma against mental illness, especially in neurodegenerative disorders as old age is often equated with the process of “disease and decay.” This can lead to a “double jeopardy” in the psychiatrically ill older population (41). Human-rights based approach targeting inequalities and discrimination in healthcare can restore inclusion, dignity and autonomy in psychogeriatric care and thus address the long-term issue of ageism.

Ageism also leads the concerning social evil of elder abuse, which is high in institutional settings. Based on WHO data, one in six individuals above 60 years age have experienced some form of abuse in the community settings within the last year (42). Ageism affects not only the older adults mentally ill but also who care them. Often it is perceived that care older adults with mental health conditions less prestigious than other positions in the health care systems, with prejudice for the professionals' career, self-esteem and their own mental health (42). Family members of older adults with mental health condition may also be victim of stigma and discrimination, with loss of personal projects and resources (including financial ones). Both ageist attitudes and consequent elder abuse have peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic and their intersections with human rights crisis, marginalization and loss of dignity in older people are quite prominent (43–45). Banerjee et al. (46) propose the complex interplay of ageism (and other forms of discrimination in older people), self-stigma, health inequality, and elder abuse that leads to compromised dignity which in association with factors such as frailty, dependence, social isolation and medical morbidities lead to “human rights crisis” in older people. The processes of “rudeness, dismissal, indifference, disregard, objectification, condescension, intrusion, restriction, labeling, discrimination, contempt, deprivation, abjection, revulsion, and assault” lead to violation of dignity in healthcare and reinforce ageist behaviors in the service providers (47). Incorporation of principles such as care, empathy, respect for individual identities, focus on safety, non-judgmental approach and social justice into geriatric mental healthcare can help combat ageism and elder abuse in lines with the Global Strategy and action plan on aging and health and the Decade of Healthy Aging 2021–2030 (48, 49).

Most older people want the same as everybody else in the general population. They want services that are reliable and dependable, easy to access and with competent staff that are sensitive and recognize diversity. When they have health needs, older adult people like to have these needs managed in a collaborative way (50). This requires a supportive community. Older people want to be close to their families if they need to receive treatment in hospital (8, 24, 35). We need innovation for this to be achieved, taking the patient's view into account and may have to adapt and use new technology in an ethical and responsible way. A review of empirical and theoretical literature on dignity in the care of older people revealed that staff attitudes and behavior, environment, culture of care, specific care activities and staff training form the major factors in deciding personal dignity. Sense of purpose and need for recognition in daily life were important considerations for dignity while in mental healthcare there was a constant tussle between degree of dignity and autonomy especially in severe mental illness and dementia (37, 43, 46). The practical wisdom of mental health professionals, social workers, case managers and policy makers and their perceptions about what constitutes dignity are vital in determining the operational interventions at place in mental healthcare settings for older people (37, 46).

Health and social professionals need to receive special education and training to care older adults with mental disorders with dignity. To educate professionals, caregivers and the lay public in mental health issues in old age is necessary to reduce the burden of mental disorders. All health and social professionals should receive information according to a knowledge based curriculum on mental health issues in old age at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Such curriculum should include the special significance in old age of the interdependence of mental, physical and social factors and the prevention and health promotion including recreational and spiritual issues (51, 52). Recovery-oriented and person-centered practices need to be at the core of healthcare. The various areas through which principles of dignity can be incorporated in psychosocial care for older people are mentioned in Table 1.

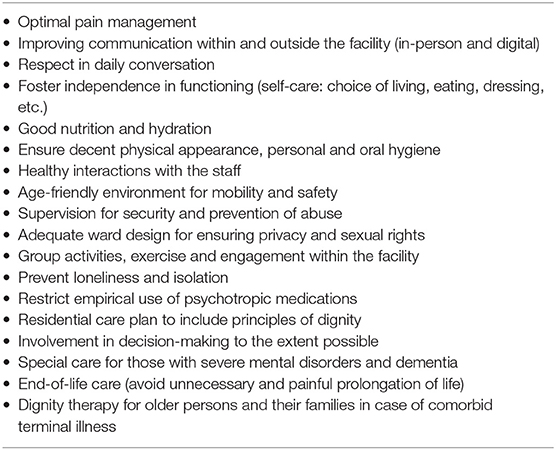

Many older people will be requiring nursing, residential and sheltered homes. Research shows that well-trained staff sensitive to their dignity and independence provide them emotional security, better quality of life and reduce risk of falls (50). Religious, spiritual and cultural values also need to be considered and incorporated into care planning (7, 53, 54). Evidence-based facets of dignity-promoting interventions in nursing home/residential settings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Ensuring dignity-based care for older people in nursing homes/residential facilities (50, 55–59).

Independence is to be encouraged. More sensibility is needed in order to understand needs and desires of people for whom it is difficult to verbalize their preferences, such as in advanced dementia, confusional states and others. Such approaches generally need well-trained staff who knows well the older individual and his or her life history (50).

Hospital managers need to play a role in ensuring that the institution promotes dignity and that staff have the capabilities to provide dignity in care, for instance by avoiding treating older people like children. Ward design can either support privacy, autonomy and dignity or make patients more vulnerable by making it harder to promote individuality (54, 60, 61). Research has suggested that bringing in pieces of their own furniture and household belongings including photographs supports the recognition of individuality (50, 53, 62).

One of the greatest challenges to care delivery in sheltered, residential and nursing care settings is that of balancing risk management with privacy whilst supporting maximum independence. There need to be environmental, relational, and procedural structures in place to ensure that the older adult have as much independence and privacy as possible whilst reducing risk because many people's greatest fear when they enter such accommodation is loss of independence (54, 60).

While good staff communication skills are fundamental to the promotion of dignity in older adults, this is a skill that can be trained. Older people living with mental illness should routinely be asked about how they would like to be addressed, and there should be meaningful interactions between those who care for the older adult and the older adult being cared for in order to avoid social isolation (59).

In addition to the treatment interventions offered, an important goal in the care of dementia is supporting quality of life, dignity and comfort: this should remain central to treatment and care delivery. Meaningful attention should be paid to the activities of daily living, the choice of treatments offered and the involvement and engagement of the individual and their family to enhance and maintain the individual's dignity (63).

Intervention programme that include the individual's family network is helpful. Family care giver's health needs should always be considered: positive health in family care givers may improve the well-being of the person with dementia and prevent care givers burn out affecting their own mental health balance. This promotes dignity by offering opportunities to care persons at the place of their choice (64).

It is necessary to develop national frameworks to protect people with impaired decision-making ability, in the respect of the person's dignity, and in accordance with the article 12 of the UN Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (10). Substitute decision making (SDM) arrangements including informal surrogate through proxies appointed by the care recipient when still competent to those who are Court-appointed. SDM measures and actions must be in the interests of the incapacitated person and their continuing necessity should be reviewed regularly. They can be tailored based on national policies and socio-cultural norms. Mechanisms should be in place for appeal and for review as well as for reporting of alleged mistreatment by SDMs (20).

The population is aging and multimorbidity and co-morbidity is no longer the exception. People who care for older adults must be willing to understand the effects of multimorbidity and co-morbidity to promote dignity and the rights of older adults.

The quality of care people with dementia receive in hospital has raised concerns in many quarters and the need for clinicians to focus on dignity for people in hospital or receiving end of life care is very important (65). In addition to having a legal framework to support dignity and the rights of older adults we also need to provide practical tools for those who care for older adults to use. Applying these tools will help the older adult to maintain their autonomy and improve their self-identity and sense of purpose.

Dying with dignity in older people is very important to relatives and to the individual concerned and the end of life presents a further challenge to older adults (66). Factors that are associated with dignity in death for an older person are complex and include the type of multi and co-morbidity, quality of relationships with family including siblings and with caregivers, enjoyment of good days prior to death, feeling contented, not feeling lonely or a burden and maintaining a feeling of being in control. We need to ensure that end of life care promotes a sense of dignity and purpose and Dignity Therapy (DT) as a psychotherapeutic intervention for people near the end of life has been explored and has the potential to enhance the dignity of the older person.

A 2005 Canadian study showed that 91% of participants were satisfied with DT with 75% of participants reporting an enhanced sense of dignity (67). DT is one of the few non-pharmacological interventions that can be useful in older adults at the end of life however this is not routinely taught in clinical practice and we should recommend this approach as an additional tool in the armory of clinicians working with older adults in end of life care.

DT is not new and is well-accepted by family members (68). Sixty family members of people who had participated in DT and later died were surveyed to understand their perspectives on DT and 95% of respondents said that it helped their loved ones and 78% reported that it had heightened their loved one's sense of dignity and reduced their suffering (68). 65% of the family members felt that this form of therapy constitutes the most important part of healthcare and nearly all of them wanted to recommend it to other families confronting a terminal illness.

A randomized controlled trial in patients with a terminal prognosis receiving palliative care in hospital or community setting compared DT with client-centered care and standard palliative care (69). Though reduction of patient distress was same in all the three interventions, DT was significantly more likely to improve family's stress, quality of life and sense of purpose in those affected. A 2015 systematic review of DT concluded that there is robust evidence to support its acceptability and suggested the need for further research into how and in what settings it should be provided (70). Another systematic review of DT in palliative care by Martínez et al. (71) showed that DT was effective in reducing psychological distress, enhancing resilience and improving depression and anxiety scores. Non-randomized studies have reported significant gains in existential distress, death anxiety and psychosocial measures, which warrant further study. Even though, DT has been used mostly in palliative care, the principals involved be translated to routine clinical care of older people so that inclusion, compassion, sense of purpose, quality of life and person-centered approach can be used rather than a purely symptom-triggered diagnosis-based management.

As professionals from different backgrounds and regions of the world we collectively pledge to employ a human rights-based lens aimed to reduce the burden of ageism, mentalism, and ableism permeating virtually every aspect of older persons' lives (3). “Leave no one behind (LNOB)” is at the heart of the United Nations' (UN's) 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (72). The UN's Decade of Healthy Aging (2021–2030) strives for all persons to enjoy peace, prosperity, and a healthy planet (48). These commendable aspirations are clearly not the reality of countless older persons who have suffered needlessly for decades. “What you permit, you promote.” Let us not permit this status quo. Let the lives sacrificed by older persons not be in vain by ensuring a positive change for the human rights of every generation of older persons. A global paradigm shift is required to transform the deeply-rooted stigma against older persons to one where every older person can fully enjoy their life with dignity and with respect. An urgent call for action is needed for a legally binding United Nations convention on the human rights of older persons.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

DB drafted the first version of the manuscript with contributions from KR, CM, and GI who also edited the manuscript. The final version was read and approved by all the authors. All authors were involved in conceptualization.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2020). World Population.

2. WHO. Mental Health of Older Adults (2017). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed September 11, 2021).

3. Rabheru K. The spectrum of ageism, mentalism, and ableism: expressions of a triple jeopardy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) (In Press). doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.06.019

4. World Needs “Revolution” in Mental Health Care–UN Rights Expert. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21689 (accessed September 11, 2021).

5. Saxena S, Hanna F. Dignity- a fundamental principle of mental health care. Indian J Med Res. (2015) 142:355–8. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.169184

6. UN General Assembly. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. United Nations Treaty Series. New York, NY: UN General Assembly (1966).

7. WHO. Quality Rights Tool Kit to Assess and Improve Quality and Human Rights in Mental Health and Social Care Facilities. Geneva: WHO (2012).

8. Jeste DV, Savla GN, Thompson WK, Vahia IV, Glorioso DK, Martin AV, Palmer BW, Rock D, Golshan S, Kraemer HC, Depp CA. Association between older age and more successful aging: critical role of resilience and depression. Am J Psychiatry. (2013) 170:188–96. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030386

9. Szmukler G. UN CRPD: equal recognition before the law. Lancet Psychiatry. (2015) 2:e29. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00369-7

10. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities (N.d.). Available online at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed September 11, 2021).

11. Smebye KL, Kirkevold M. K., Engedal. Ethical dilemmas concerning autonomy when persons with dementia wish to live at home: a qualitative, hermeneutic study. BMJ Health Serv Res. (2016) 16:16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1217-1

12. Leibing A. Geriatrics and humanism: dementia and fallacies of care. J Aging Stud. (2019) 51:100796. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2019.100796

13. Caplan A. L. Why autonomy needs help. J Med Ethics. (2014) 40:301–2. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-100492

14. Nordenfelt L. Dignity in the care of the older adult. Med Health Care Philos. (2003) 6:103–10. doi: 10.1023/A:1024110810373

15. Gallagher A, Li S, Wainwright P, Jones IR, Lee D. Dignity in the care of older people–a review of the theoretical and empirical literature. BMC Nurs. (2008) 7:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-7-11

16. Picker Institute Europe. Improving Patients' Experience: Sharing Good Care No. 11 Stroke Care: The National Picture. Oxford: Picker Institute Europe (2005).

17. Gallagher A. Editorial: what do we know about dignity in care? Nurs Ethics. (2011) 18: 471–3. doi: 10.1177/0969733011413845

19. World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. New York, NY: WHO (1948).

20. Katona C, Chiu E, Adelman S, Baloyannis S, Camus V, Firmino H, et al. World psychiatric association section of old age psychiatry consenus statement on ethics and capacity in older people with mental disorders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2009) 24:1319–24. doi: 10.1002/gps.2279

21. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving humen subjects. JAMA. (2013) 310:2191–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053

22. Council of Europe. Convention for the protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. ETS N° 164. Oviedo. Strasbourg: Council of Europe (1997).

23. Høy B, Wagner L, Hall EO. The elderly patient's dignity. The core value of health. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. (2007) 2:160–8. doi: 10.1080/17482620701472447

24. Ivbijaro G, Kolkiewicz L, Goldberg D, Brooks C, Enum Y. Promoting dignity in the care of the older adult. In: de Mendonça Lima C, Ivbijaro G, editors. Primary Care Mental Health in Older People. Cham: Springer (2019). p. 73–82.

25. Lothian K, Philp I. Care of older people: maintaining the dignity and autonomy of older people in the healthcare setting. BMJ. (2001) 322:668–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7287.668

26. Clancy A, Simonsen N, Lind J, Liveng A, Johannessen A. The meaning of dignity for older adults: a meta-synthesis. Nurs Ethics. (2020) 28:878–94. doi: 10.1177/0969733020928134

27. Hadlaczky G, Hökby S, Mkrtchian A, Carli V, Wasserman D. Mental Health First Aid is an effective public health intervention for improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2014) 26:467–75. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.924910

28. Mann J. Dignity and health: the UDHR's Revolutionary First Article. Health Hum Rights. (1998) 3: 30–8. doi: 10.2307/4065297

31. Halpern J. What is clinical empathy? J Gen Intern Med. (2003) 18: 670–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21017.x

32. Lee T. How to Spread Empathy in Healthcare. Harvard Business Review. (2014). Available online at: https://hbr.org/2014/07/how-to-spread-empathy-in-health-care (accessed September 11, 2021).

33. de Mendonça Lima CA. Social determinants of health and promotion of mental health in old age. In: Bährer-Kohler S., editor. Social Determinants and Mental Health. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc, (2011). p. 203–13.

34. Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, Marmot M. Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2014) 26:392–407. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.928270

35. Silva M, Loureiro A, Cardoso G. Social determinants of mental health: a review of the evidence. Eur J Psychiatry. (2016) 30:259–92. Available online at: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S0213-61632016000400004&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

36. Searight HR, Gafford J. Cultural diversity at the end of life: issues and guidelines for family physicians. Am Fam Phys. (2005) 71:515–22.

37. Minoletti A. 4.2. Promoting Mental Health Dignity–The Role of Secondary Care Mental Health Services. Dignity In Mental Health. Available online at: https://crehpsy-documentation.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=227#page=32 (accessed September 11, 2021).

38. Iversen TN, Larsen L, Solem PE. A conceptual analysis of ageism. Nordic Psychol. (2009) 61:4–22. doi: 10.1027/1901-2276.61.3.4

39. World Health Organization. Global Report on Ageism (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/demographic-change-and-healthy-ageing/combatting-ageism/global-report-on-ageism (accessed September 11, 2021).

40. Chang ES, Kannoth S, Levy S, Wang SY, Lee JE, Levy BR. Global reach of ageism on older persons' health: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0220857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220857

41. Mikton C, de la Fuente-Núñez V, Officer A, Krug E. Ageism: a social determinant of health that has come of age. Lancet. (2021) 397:1333–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00524-9

42. World Health Organization. Elder Abuse (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse (accessed September 11, 2021).

43. D'cruz M, Banerjee D. “An invisible human rights crisis”: the marginalization of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic–an advocacy review. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 292:113369. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113369

44. Monahan C, Macdonald J, Lytle A, Apriceno M, Levy SR. COVID-19 and ageism: how positive and negative responses impact older adults and society. Am Psychol. (2020) 75:887–96. doi: 10.1037/amp0000699

45. Moradi M, Navab E, Sharifi F, Namadi B, Rahimidoost M. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the elderly: a systematic review. Iran J Ageing. (2021) 16:2–9. doi: 10.32598/sija.16.1.3106.1

46. Banerjee D, Rabheru K, de Mendonca Lima CA, Ivbijaro G. Role of dignity in mental health care: impact on ageism and human rights of older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) 29:1000–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.05.011

47. Jacobson N. Dignity violation in health care. Qual Health Res. (2009) 19:1536–47. doi: 10.1177/1049732309349809

48. World Health Organization. UN Decade of Healthy Ageing 2021-2030 (N.d.). Available online at: https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing#:~:text=The%20United%20Nations%20Decade%20of,improve%20the%20lives%20of%20older (accessed September 11, 2021).

49. World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health (2017). Available online at: https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf (accessed September 11, 2021).

50. Levenson R, Jeyasingham M, Joule N. Looking Forward to Care in Old Age. Care Services Inquiry Working Paper. London: Kings Fund (2005).

51. WHO/WPA. Education in psychiatry of the elderly: a technical consensus statement. WHO/MNH/MND/98.4. Geneva: WHO (1998).

52. Gustafson L, Burns A, Katona C, Bertolote JM, Camus V, Copeland JR, et al. Skill-based objectives for specialist training in old age psychiatry. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2003) 18:686–93. doi: 10.1002/gps.899

53. Bland R. Independence, privacy and risk: two contrasting approaches to residential care for older people. Ageing Soc. (1999) 19:539–60. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X99007497

54. Leibing A, Guberman N, Wiles J. Liminal homes: older people, loss of capacities, and the present future of living spaces. J Aging Stud. (2015) 37:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.12.002

55. Hall S, Dodd RH, Higginson IJ. Maintaining dignity for residents of care homes: a qualitative study of the views of care home staff, community nurses, residents and their families. Geriatr Nurs. (2014) 35:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.10.012

56. Wårdh I, Andersson L, Sörensen S. Staff attitudes to oral health. A comparative study of registered nurses, nursing assistants and home care aides. Gerodontology. (1997) 14:28–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1997.00028.x

57. Stanley SH, Laugharne JDE. Clinical guidelines for the physical care of mental health consumers: a comprehensive assessment of monitoring package for mental health and primary care clinicians. Austr N Z J Psychiatry. (2011) 45:824–9. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.614591

58. Cederholm T, Barazzoni R, Austin P, Ballmer P, Biolo G, Bischoff SC, et al. ESPEN guidelines and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin Nutr. (2017) 36:49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.09.004

59. Caris-Verhallen WMCM, Kerkstra A, Bensing JM. The role of communication in nursing care for older adult people: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. (1997) 25:915–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025915.x

60. Baillie L. Patient dignity in an acute hospital setting: a case study. Int J Nurs Stud. (2009) 46:23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.003

61. Walsh K, Kwanko I. Nurses' and patients' perceptions of dignity. Int J Nurs Pract. (2002) 8:143–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172X.2002.00355.x

62. Anttonen A Haïkïö. Care “going market”: finnish older adult-care policies in transition. Nordic J Soc Res. (2011) 2:70–90. doi: 10.7577/njsr.2050

63. Volicer L. Goals of care in advanced dementia: quality of life, dignity and comfort. J Nutr Health Ageing. (2007) 11:481.

64. Smits CHM, de Lange J, Dröes R-M, Meiland F, Vernooij-Dassen M, Pot AM. Effects of combined intervention programmes for people with dementia living at home and their caregivers: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2007) 22:1181–93. doi: 10.1002/gps.1805

65. Bridges J, Wilkinson C. Achieving dignity for older people with dementia in hospital. Nurs Standard. (2011) 25:42–7. doi: 10.7748/ns2011.03.25.29.42.c8402

66. Van Gennip IE, Pasman HRW, Kaspers PJ, Oosterveld-Vlug MG, Willems DL, Deeg DLH, Onwuteaka-Philipsen. Death with dignity from the perspective of the surviving family: a survey study among family caregivers of deceased older adults. Palliat Med. (2013) 27:616–24. doi: 10.1177/0269216313483185

67. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. (2005) 23:5520–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.391

68. McClement S, Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, Kristjanson LJ. Dignity therapy: family member perspectives. J Palliat Med. (2007) 10:1076–82. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0002

69. Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, McClement S, Hack TF, Hassard T, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. (2011) 12:753–62. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X

70. Fitchett G, Emanuel L, Handzo G, Boyken L, Wilkie DJ. Care of the human spirit and the role of dignity therapy: a systematic review of dignity therapy research. BMC Palliat Care. (2015) 14:8. doi: 10.1186/s12904-015-0007-1

71. Martínez M, Arantzamendi M, Belar A, Carrasco JM, Carvajal A, Rullán M, Centeno C. “Dignity therapy”, a promising intervention in palliative care: a comprehensive systematic literature review. Palliat Med. (2017) 31:492–509. doi: 10.1177/0269216316665562

72. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. THE 17 GOALS (N.d.). Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed September 11, 2021).

Keywords: dignity, human rights, older people, ageism, elder abuse, mental health

Citation: Banerjee D, Rabheru K, Ivbijaro G and Mendonca Lima CAd (2021) Dignity of Older Persons With Mental Health Conditions: Why Should Clinicians Care? Front. Psychiatry 12:774533. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.774533

Received: 12 September 2021; Accepted: 11 October 2021;

Published: 12 November 2021.

Edited by:

Gianfranco Spalletta, Santa Lucia Foundation (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Paroma Mitra, New York University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Banerjee, Rabheru, Ivbijaro and Mendonca Lima. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Debanjan Banerjee, ZHIuZGphbjg4QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.