- 1Biological Psychiatry Laboratory, Jiangxi Mental Hospital/Affiliated Mental Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Jiangxi Mental Hospital/Affiliated Mental Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China

- 3Jiangxi Provincial Clinical Research Center on Mental Disorders, Nanchang, China

- 4Department of Neurology, The Second Clinical Medical College, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Quanzhou, China

Accumulating evidence has suggested a dysfunction of synaptic plasticity in the pathophysiology of depression. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), an endogenous gasotransmitter that regulates synaptic plasticity, has been demonstrated to contribute to depressive-like behaviors in rodents. The current study investigated the relationship between plasma H2S levels and the depressive symptoms in patients with depression. Forty-seven depressed patients and 51 healthy individuals were recruited in this study. The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) was used to evaluate depressive symptoms for all subjects and the reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) was used to measure plasmaH2S levels. We found that plasma H2S levels were significantly lower in patients with depression relative to healthy individuals (P < 0.001). Compared with healthy controls (1.02 ± 0.34 μmol/L), the plasma H2S level significantly decreased in patients with mild depression (0.84 ± 0.28 μmol/L), with moderate depression (0.62 ± 0.21μmol/L), and with severe depression (0.38 ± 0.18 μmol/L). Correlation analysis revealed that plasma H2S levels were significantly negatively correlated with the HAMD-17 scores in patients (r = −0.484, P = 0.001). Multivariate linear regression analysis showed that plasma H2S was an independent contributor to the HAMD-17 score in patients (B = −0.360, t = −2.550, P = 0.015). Collectively, these results suggest that decreased H2S is involved in the pathophysiology of depression, and plasma H2S might be a potential indicator for depression severity.

Introduction

Depression is a common illness with more than 264 million people affected in the worldwide (1). Person with depressive disorder experiences depressed mood, loss of interest and enjoyment, and reduced energy leading to diminished activity for at least 2 weeks. Depression results from a complex interaction of social, psychological and biological factors (2). Although the neurobiological mechanisms underlying depression have not been recognized completely, emerging evidence suggests a dysfunction of synaptic plasticity in the pathophysiology of depression (3–5). For example, exposure to chronic stress was shown to induce dendritic atrophy and spine loss in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (6–8). Impaired long-term potentiation (LTP) was observed in the hippocampus of the chronic stress mice model of depression (9). Restoration of stress-induced changes in synaptic plasticity within the corticoaccumbal glutamate circuit prevented the behavioral vulnerability of mice to chronic stress (10).

Synaptic plasticity is an experience-dependent change in synaptic strength at preexisting synapses, in which one type of ionotropic glutamate receptors, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR), plays a key role (11). Numerous studies have reported that there are abnormal gene expression and function in NMDARs in the hippocampus of depressed patients (12–14). Chronic stress could reduce the expression of NMDARs in the hippocampus in rodents (15–17). Preclinical studies indicate that both acute and chronic stress can perturb the normal balance between synaptic potentiation and depression in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (18–20). Furthermore, a number of experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that improving actions of antidepressants are associated with restoration of maladaptive brain plasticity (21–23).

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a member of the gasotransmitter family that is associated with the maintenance of neuronal plasticity, excitability, and homeostatic functions (24). It is mainly produced by the enzyme cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) in the brain and the enzyme cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) in the peripheral tissues (25). Abe and Kimura first demonstrated the influences of H2S on synaptic plasticity. They showed that physiological concentrations of H2S facilitated the induction of hippocampal LTP by increasing the activity of NMDARs (26). Inhibition of H2S generation would lead to a reduction in NMDAR-mediated synaptic response and cause an impairment of LTP in the amygdala (27). Gas can freely diffuse across cell membranes and blood-brain barrier. Previous studies have demonstrated that intraperitoneal injection of NaHS (an H2S donor) or inhalation of H2S can increase brain H2S content and promote amygdalar LTP and emotional memory in rats (28), and systemic administration of NaHS could elevate hippocampal H2S level and dramatically reversed the cognitive and synaptic plasticity deficits in APP/PS1 transgenic mice (29).

Since H2S has an important regulatory role in synaptic plasticity, some studies have explored its role in depression. Chen et al. reported that chronic intraperitoneal treatment with NaHS produced a specific antidepressant-like effect in non-stressed mice and rats (30). Administration of NaHS significantly alleviated the depressive-like behaviors in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats (31). Moreover, a recent study showed that decreased level of endogenous H2S in the hippocampus was responsible for the abnormal behaviors induced by chronic unpredictable mild stress, and the depressive-like behavior of rats could be alleviated within a few hours by increasing H2S level in the hippocampus through giving H2S donor or inhaling H2S (32). However, whether plasma H2S levels are changed in patients with depression and its association with the severity of depression remains unknown. In this study, we further explored the role of H2S signaling in the pathophysiology of depression by investigating whether (1) plasma H2S level was altered in patients with depression and (2) there were any relationships between H2S levels and depressive symptoms in these patients.

Method

Subjects

Forty-seven inpatients with acute depressive episode (male/female = 20/27) were recruited from Jiangxi Mental Hospital. Two psychiatrists have confirmed the diagnosis of depression based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). The exclusion criteria included any other axis I or axis II DSM-IV diagnoses, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance abuse, anxiety disorder and so on. Fifty-one healthy controls (male/female = 28/23), matched with the patients by gender, age, education years, and body mass index (BMI), were recruited from the local community. Subject with a personal or family history of mental illness was excluded from control group. The exclusion criteria for all participants also included current pregnancy, autoimmune, allergic and neoplastic diseases, as well as other physical diseases that had occurred in the past 3 months, including hypertension, diabetes, heart or brain infarction.

The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) was used to evaluate depressive symptoms for all subjects (Supplementary Table 1) (33). The severity of depression was ranked on a HAMD-17 score: mild depression (8–17), moderate depression (18–24), and severe depression (>24) (34). To investigate whether antidepressants affected plasma H2S level, the depressed patients were divided into an antidepressant-treatment subgroup (n = 31) and an antidepressant-naive subgroup (n = 16). Subjects who were free of any antidepressant treatment for at least 1 month were defined as antidepressant-naive patients.

The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Jiangxi Mental Hospital and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent was provided from each subject, or his or her parents/guardians.

Measurement of Plasma H2S

Whole blood from subjects who fasted overnight was collected into tubes with EDTA. After collection, samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min at the temperature of 4°C and then the plasma was separated, aliquoted, and stored at−80°C until analysis.

The concentration of H2S in plasma was measured using a monobromobimane method coupled with reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (35). Free H2S in the plasma was analyzed by RP-HPLC after derivatization with excess monobromobimane (MBB) to form stable sulfide dibimane derivative. 30 μL of sample was pipetted and mixed with 70 μL of 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 9.5, 0.1 mM DTPA), followed by addition of 50 μL of 10 mM MBB. The reaction was terminated by adding 50 μL of 200 mM 5-sulfosalicylic acid at 30 mins later. After centrifugation, the supernatant was determined using an Agilent 1,220 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse XDB-C18 column. The content of plasma H2S was calculated based on sulfidedibimane standard curves.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed with the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) 18.0 software. We compared categorical variables between patients and healthy controls using a chi-squared test. The continuous variables that were distributed normally were compared by Student's t-test and the independent variables that did not fit the normal distribution were analyzed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Mann-Whitney U tests. The relationships between plasma H2S and other variables were determined by Pearson correlation analysis and the independent relationships were analyzed by multivariate linear regression analysis. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

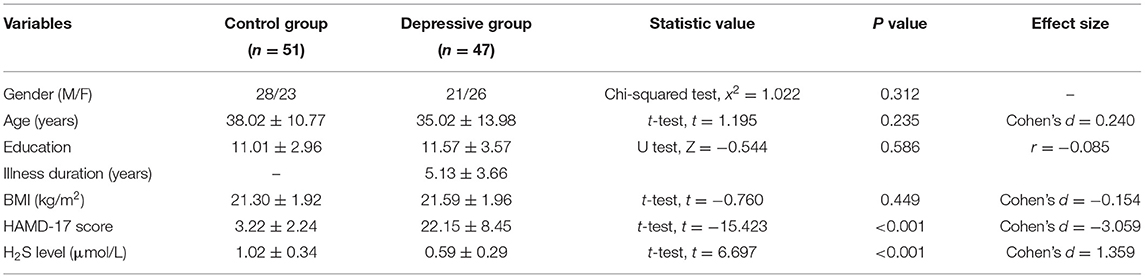

Forty-seven inpatients with depression (21 male, 26 female) and 51 healthy controls (28 male, 23 female) was enrolled in this study. Table 1 shows the demographic variables and the clinical values of control group and depressive group. There was no significant difference between two groups in terms of gender, age and BMI. The mean HAMD-17 score in depressive patients was statistically higher than that in the control group (22.15 ± 8.45 in depressive group vs. 3.22 ± 2.24 in control group, P < 0.001).

The plasma level of H2S in the depressive patients was significantly lower than that in healthy controls (patients: 0.59 ± 0.29 μmol/L, controls: 1.02 ± 0.34 μmol/L; t = 6.697, P < 0.001) (Table 1). No significant difference was observed in plasma H2S level between male and female in both groups (both P > 0.05). For depressive patients, the level of plasma H2S was not different between antidepressant-treatment and antidepressant-naïve subgroup (t = 0.218, P = 0.828). A two-way ANOVA for H2S level in depressive patients showed that there was no significant main effect of gender (F(1,43) = 2.384, P = 0.130), no significant main effect of antidepressant treatment (F(1,43) = 0.036, P = 0.851) and no main effect of gender × antidepressant treatment (F(1,43) = 0.731, P = 0.397).

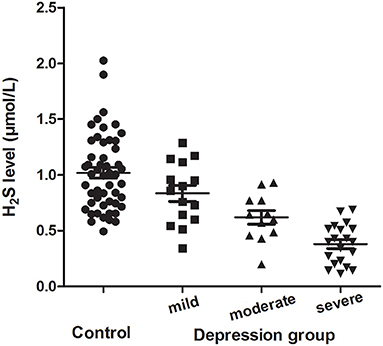

Among 47 depressive patients, 15 patients (31.9%) had mild depression, 12 patients (25.5%) had moderate depression, and 20 patients (42.6%) had severe depression. The level of plasma H2S in mild, moderate and severe depressive patients was 0.84 ± 0.28, 0.62 ± 0.21 and 0.38 ± 0.18 μmol/L, respectively. One-way ANOVA revealed that there were significant differences among healthy controls, mild depressive, moderate depressive and severe depressive patients (F(3, 97) = 24.984, P < 0.001). Bonferroni post hoc multiple tests for depressive subgroups showed that there was a significant decreased trend of the plasma H2S level among mild depressive patients compared to moderate depressive patients (P = 0.047), and moderate depressive patients compared to severe depressive patients (P = 0.015) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Plasma H2S levels (mean ± SD) in the controls and the mild, moderate and severe depression group.

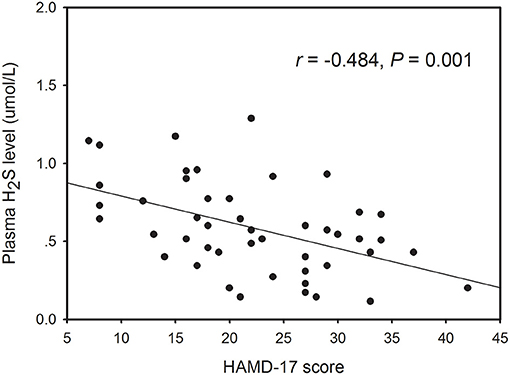

Within the healthy control subjects, there no significant correlation between plasma H2S level and any demographic variable including gender, age, and BMI. However, Pearson correlation analysis revealed that the plasma H2S level was significantly correlated with age (r = −0.296, P = 0.043; Supplementary Figure 1) and HAMD-17 score (r = −0.484, P = 0.001; Figure 2) in patients with depression. Partial correlation analysis showed that the correlation between H2S levels and theHAMD-17 scores was still significant when controlling for gender, age, education years, BMI, and duration of illness (r = −0.374, P = 0.015). Finally, we conducted multivariate regression analysis to elucidate independent determinants of HAMD-17 scores (R2 = 0.586) and found that plasma H2S was an independent contributor to the HAMD-17 scores (B = −0.360, t = −2.550, P = 0.015) (Table 2).

Table 2. Correlations between plasma H2S levels, demographic characteristics and clinical variables in patients with depression.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that H2S is implicated in the pathophysiology of depression in rodents (30–32). In this study, the plasma levels of H2S were determined in Chinese patients with depression. We found a significant decrease in plasma H2S level in depressive patients compared to healthy controls, and decreased plasma H2S level was significantly correlated with the severity of depression.

H2S is an endogenous gasotransmitter with numerous homeostatic functions, such as neurotransmission and neuromodulation (24). A large number of studies have demonstrated that a dysfunction of H2S signaling takes a part in the pathophysiology of many neuropsychiatric disorders. The H2S level was decreased in the hippocampus of Alzheimer's disease (AD) mice and treating AD mice with NaHS reversed the impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity and cognitive function (29, 36). Plasma H2S level is significantly decreased in both schizophrenia and AD patients, and has a correlation with the severity of cognitive impairments in these patients (35, 37). Hou et al. reported that endogenous H2S was decreased in the hippocampus of depressive model rats and responsible for the depressive-like behaviors of rats (32). In consistent with these results, we here showed that plasma H2S levels were significantly decreased in depressed patients and were correlated with the severity of depressive symptoms of patients, providing evidence for the contribution of H2S signaling to the pathogenesis of depression. It should be noted that change of plasma H2S in patients might also result from the treatment of antidepressants. However, we enrolled inpatients with acute depressive episode who had HAMD scores >8 in this study. Although some of the patients were taking antidepressants at the time of inclusion, the HAMD score showed that they were still depressed, suggesting that current antidepressants they used were not effective in improving their depressive symptoms. Indeed, meta-analyses of clinical trials have reported that more than 60% of patients fail to obtain significant or sustained remission with any single traditional antidepressant drug, with approximately one third of all depressed individuals failing two or more first-line antidepressant courses of treatment, consistent with the diagnosis of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) (38, 39). Our present study found that the level of plasma H2S was not different between antidepressant-treatment and antidepressant-naive subgroups in depressive patients, indicating that antidepressants alone do not affect plasma H2S levels in those patients whose depressive symptoms have not improved significantly. Therefore, in combination with the finding that endogenous H2S was decreased in the hippocampus of depressive rats (32), we postulate that change of plasma H2S level in patients is related to the illness per se, rather than secondary to antidepressant treatment. However, the mechanisms underlying the reduction of H2S in depression are still needed further investigations.

The HAMD is the most widely used scale for patient selection and follow-up in depression treatment studies (40, 41). We used HAMD-17 to evaluate the severity of depressive symptoms in the present study. Correlation analysis showed that there was a significantly negative correlation between plasma H2S levels and the HAMD-17 scores in depressive patients. Partial correlation analysis demonstrated that the correlation between H2S levels and the HAMD-17 scores was still significant when controlling for gender, age, education years, BMI, and duration of illness. Multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that plasma H2S level was negatively associated with HAMD-17 score. These results suggest that patients with lower H2S levels would be more likely to have severer depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the level of plasma H2S was decreased gradually from mild depression to moderate depression, and from moderate depression to severe depression, also indicating that plasma H2S is associated with the severity of depression. Therefore, the plasma H2S level may be served as a biomarker to evaluate the severity of depression.

There are some limitations in this study. First, the sample size was relatively small and all subjects were recruited from a single hospital. Replication in larger and multicenter samples is required to validate this conclusion. Second, H2S levels were measured in plasma, but not in the brain. Whether H2S level in the brain changes parallel with the level in plasma in patients is still unclear. Third, this was across-sectional study. Future studies are needed to elucidate the role of plasma H2S in the progression of depression. Additionally, although an association of decreased plasma H2S and the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with depression was found in this study, the mechanisms through which H2S affects depressive behaviors are needed to be investigated.

Conclusion

Our present study shows that patients with depression have lower plasma H2S levels than healthy controls, and decreased H2S was associated with the severity of depressive symptoms inpatients. These results demonstrate an important role of H2S signaling in the pathophysiology of depression, suggesting that plasma H2S level may be a potential biomarker for the severity of depression.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Jiangxi Mental Hospital. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

Y-JY, C-NC, J-QZ, Q-SL, YL, and S-ZJ participated in clinical data collection and lab data analysis. Y-JY and BW designed the study, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060258 and 81760254). It was also supported by the Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20202BAB206026, 20202BAB216012, 20202BBG73022, and 2020BCG74002), the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2019J01164) and the Scientific Foundation of Quanzhou City for High Level Talents (2019C075R).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.765664/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, Fukutaki K, Fullman N, Mcgaughey M, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet. (2018) 392:2052–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31694-5

2. Papadimitriou G. The “Biopsychosocial Model”: 40 years of application in Psychiatry. Psychiatriki. (2017) 28:107–10. doi: 10.22365/jpsych.2017.282.107

3. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, Krystal JH. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. (2016) 22:238–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.4050

4. Aleksandrova LR, Wang YT, Phillips AG. Evaluation of the Wistar-Kyoto rat model of depression and the role of synaptic plasticity in depression and antidepressant response. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2019) 105:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.07.007

5. Price RB, Duman R. Neuroplasticity in cognitive and psychological mechanisms of depression: an integrative model. Mol Psychiatry. (2020) 25:530–43. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0615-x

6. Magarinos AM, Mcewen BS. Stress-induced atrophy of apical dendrites of hippocampal CA3c neurons: comparison of stressors. Neuroscience. (1995) 69:83–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00256-I

7. Sandi C, Davies HA, Cordero MI, Rodriguez JJ, Popov VI, Stewart MG. Rapid reversal of stress induced loss of synapses in CA3 of rat hippocampus following water maze training. Eur J Neurosci. (2003) 17:2447–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02675.x

8. Goldwater DS, Pavlides C, Hunter RG, Bloss EB, Hof PR, Mcewen BS, et al. Structural and functional alterations to rat medial prefrontal cortex following chronic restraint stress and recovery. Neuroscience. (2009) 164:798–808. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.053

9. Yang Y, Ju W, Zhang H, Sun L. Effect of Ketamine on LTP and NMDAR EPSC in hippocampus of the chronic social defeat stress mice model of depression. Front Behav Neurosci. (2018) 12:229. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00229

10. Jiang B, Wang W, Wang F, Hu ZL, Xiao JL, Yang S, et al. The stability of NR2B in the nucleus accumbens controls behavioral and synaptic adaptations to chronic stress. Biol Psychiatry. (2013) 74:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.10.031

11. Citri A, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2008) 33:18–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301559

12. Feyissa AM, Chandran A, Stockmeier CA, Karolewicz B. Reduced levels of NR2A and NR2B subunits of NMDA receptor and PSD-95 in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2009) 33:70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.10.005

13. Amidfar M, Woelfer M, Reus GZ, Quevedo J, Walter M, Kim YK. The role of NMDA receptor in neurobiology and treatment of major depressive disorder: evidence from translational research. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 94:109668. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109668

14. Adell A. Brain NMDA Receptors in Schizophrenia and depression. Biomolecules. (2020) 10:947. doi: 10.3390/biom10060947

15. Lehner M, Wislowska-Stanek A, Gryz M, Sobolewska A, Turzynska D, Chmielewska N, et al. The co-expression of GluN2B subunits of the NMDA receptors and glucocorticoid receptors after chronic restraint stress in low and high anxiety rats. Behav Brain Res. (2017) 319:124–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.11.004

16. Pacheco A, Aguayo FI, Aliaga E, Munoz M, Garcia-Rojo G, Olave FA, et al. Chronic stress triggers expression of immediate early genes and differentially affects the expression of AMPA and NMDA subunits in dorsal and ventral hippocampus of rats. Front Mol Neurosci. (2017) 10:244. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00244

17. Elhussiny MEA, Carini G, Mingardi J, Tornese P, Sala N, Bono F, et al. Modulation by chronic stress and ketamine of ionotropic AMPA/NMDA and metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat hippocampus. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 104:110033. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110033

18. Holderbach R, Clark K, Moreau JL, Bischofberger J, Normann C. Enhanced long-term synaptic depression in an animal model of depression. Biol Psychiatry. (2007) 62:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.007

19. Maggio N, Segal M. Persistent changes in ability to express long-term potentiation/depression in the rat hippocampus after juvenile/adult stress. Biol Psychiatry. (2011) 69:748–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.026

20. Chattarji S, Tomar A, Suvrathan A, Ghosh S, Rahman MM. Neighborhood matters: divergent patterns of stress-induced plasticity across the brain. Nat Neurosci. (2015) 18:1364–75. doi: 10.1038/nn.4115

21. Maya Vetencourt JF, Sale A, Viegi A, Baroncelli L, De Pasquale R, O'leary OF. The antidepressant fluoxetine restores plasticity in the adult visual cortex. Science. (2008) 320:385–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1150516

22. Workman ER, Niere F, Raab-Graham KF. Engaging homeostatic plasticity to treat depression. Mol Psychiatry. (2018) 23:26–35. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.225

23. Moda-Sava RN, Murdock MH, Parekh PK, Fetcho RN, Huang BS, Huynh TN, et al. Sustained rescue of prefrontal circuit dysfunction by antidepressant-induced spine formation. Science. (2019) 11:364. doi: 10.1126/science.aat8078

24. Shefa U, Kim D, Kim MS, Jeong NY, Jung J. Roles of gasotransmitters in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric conditions. Neural Plast. (2018) 2018:1824713. doi: 10.1155/2018/1824713

25. Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide: from brain to gut. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2010) 12:1111–23. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2919

26. Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci. (1996) 16:1066–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996

27. Chen HB, Wu WN, Wang W, Gu XH, Yu B, Wei B, et al. Cystathionine-beta-synthase-derived hydrogen sulfide is required for amygdalar long-term potentiation and cued fear memory in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. (2017) 155:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2017.03.002

28. Wang CM, Yang YJ, Zhang JT, Liu J, Guan XL, Li MX, et al. Regulation of emotional memory by hydrogen sulfide: role of GluN2B-containing NMDA receptor in the amygdala. J Neurochem. (2015) 132:124–34. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12961

29. Yang YJ, Zhao Y, Yu B, Xu GG, Wang W, Zhan JQ, et al. GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors contribute to the beneficial effects of hydrogen sulfide on cognitive and synaptic plasticity deficits in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neuroscience. (2016) 335:170–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.08.033

30. Chen WL, Xie B, Zhang C, Xu KL, Niu YY, Tang XQ, et al. Antidepressant-like and anxiolytic-like effects of hydrogen sulfide in behavioral models of depression and anxiety. Behav Pharmacol. (2013) 24:590–7. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283654258

31. Tang ZJ, Zou W, Yuan J, Zhang P, Tian Y, Xiao ZF, et al. Antidepressant-like and anxiolytic-like effects of hydrogen sulfide in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats through inhibition of hippocampal oxidative stress. Behav Pharmacol. (2015) 26:427–35. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000143

32. Hou XY, Hu ZL, Zhang DZ, Lu W, Zhou J, Wu PF, et al. Rapid antidepressant effect of hydrogen sulfide: evidence for activation of mTORC1-TrkB-AMPA receptor pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2017) 27:472–88. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6737

33. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1960) 23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

34. Lin CH, Park C, Mcintyre RS. Early improvement in HAMD-17 and HAMD-7 scores predict response and remission in depressed patients treated with fluoxetine or electroconvulsive therapy. J Affect Disord. (2019) 253:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.082

35. Xiong JW, Wei B, Li YK, Zhan JQ, Jiang SZ, Chen HB, et al. Decreased plasma levels of gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide in patients with schizophrenia: correlation with psychopathology and cognition. Psychopharmacology. (2018) 235:2267–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4923-7

36. He XL, Yan N, Zhang H, Qi YW, Zhu LJ, Liu MJ, et al. Hydrogen sulfide improves spatial memory impairment and decreases production of Abeta in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurochem Int. (2014) 67:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.01.004

37. Liu XQ, Jiang P, Huang H, Yan Y. Plasma levels of endogenous hydrogen sulfide and homocysteine in patients with Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia and the significance thereof. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. (2008) 88:2246–9. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.659402

38. Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Levitt A. The sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) trial: a review. Can J Psychiatry. (2010) 55:126–35. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500303

39. Gerhard DM, Wohleb ES, Duman RS. Emerging treatment mechanisms for depression: focus on glutamate and synaptic plasticity. Drug Discov Today. (2016) 21:454–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.01.016

40. Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. (1979) 134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

Keywords: depression, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), plasma, severity, correlation

Citation: Yang Y-J, Chen C-N, Zhan J-Q, Liu Q-S, Liu Y, Jiang S-Z and Wei B (2021) Decreased Plasma Hydrogen Sulfide Level Is Associated With the Severity of Depression in Patients With Depressive Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 12:765664. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.765664

Received: 27 August 2021; Accepted: 22 October 2021;

Published: 11 November 2021.

Edited by:

Sheng Wei, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, ChinaReviewed by:

Chong Chen, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, JapanRuiyong Wu, Yangzhou University, China

Copyright © 2021 Yang, Chen, Zhan, Liu, Liu, Jiang and Wei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bo Wei, anhtaF93YkAxNjMuY29t

Yuan-Jian Yang

Yuan-Jian Yang Chun-Nuan Chen4

Chun-Nuan Chen4 Bo Wei

Bo Wei