95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 09 September 2021

Sec. Sleep Disorders

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.733998

This article is part of the Research Topic Interaction Between Neuropsychiatry and Sleep Disorders: from Mechanism to Clinical Practice View all 19 articles

Objective: To observe the changes in sleep characteristics and BDI scores in patients with short-term insomnia disorder (SID) using a longitudinal observational study.

Methods: Fifty-four patients who met the criteria for SID of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition, were recruited. Depression levels were assessed using the Beck depression inventory (BDI) at enrollment and after 3 months of follow-up, respectively. Sleep characteristics were assessed by polysomnography.

Results: After 3 months of follow-up, the group was divided into SID with increased BDI score (BDI >15) and SID with normal BDI score (BDI ≤ 15) according to the total BDI score of the second assessment. The differences in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep latency, REM sleep arousal index, and NREM sleep arousal index between the two groups were statistically significant. The total BDI score was positively correlated with REM and NREM sleep arousal index and negatively correlated with REM sleep latency, which were analyzed by Pearson correlation coefficient. Multiple linear regression was used to construct a regression model to predict the risk of depression in which the prediction accuracy reached 83.7%.

Conclusion: REM sleep fragmentation is closely associated with future depressive status in patients with SID and is expected to become an index of estimating depression risk.

Insomnia disorder is the most common sleep disorder worldwide. It is an important public health problem not only because of its high rate of prevalence and disability, but also because insomnia has been found to be an important risk factor for various psychiatric disorders (1–3), especially major depression disorder. Studies show that people with insomnia are two to three times more likely to develop depression than those without insomnia (4, 5), and other researchers believe that the core problem of insomnia involves an overactive arousal system. During sleep, frequent arousals can lead to unstable or fragmented sleep architecture (6–8). Because rapid eye movement (REM) sleep represents a state of high brain arousal during sleep, it plays a key role in insomnia (9–11). At the same time, REM sleep is shown to play an important role in the reprocessing and consolidation of emotional experiences in the limbic system (12). A previous study (13) finds that changes in REM sleep are frequently observed in patients with major depression, for example, shorter REM sleep latency, increased REM sleep duration, and REM density. Excessive arousal and REM sleep fragmentation play an important role in the mood regulation of insomnia and depression by affecting the elimination of negative emotions. The bidirectional relationship between these two disorders may also suggest that instability of REM sleep has a particular impact on insomnia and depression and may be a key factor in the common mechanism of action of insomnia and depression (11, 14). The concept of instability of REM sleep is based on evidence showing increased micro- and macro-arousals during REM sleep in insomnia patients (15). REM sleep is involved in processes that affect emotional homeostasis in the brain. Prolonged and sustained disturbance of REM sleep through arousal or wake intrusion leads to decreased REM stability during sleep (16). REM sleep fragmentation is one of the pathological bases of depression in patients with chronic insomnia (17, 18). Therefore, stability of REM sleep is important for insomnia patients.

In our study, polysomnography (PSG) was used to analyze and assess the sleep architecture of patients with short-term insomnia, to explore the effects of REM sleep segments and REM-related sleep architecture on the mood of patients with short-term insomnia disorder (SID), and to try to construct regression models that can better predict the risk of depression.

Patients attended the sleep clinic and psychological consultation clinic of Ningbo First Hospital from January 2019 to September 2020. They met the diagnostic criteria for SID of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition (19): age >18 years, male and female, total duration of illness <3 months, able to cooperate with the completion of questionnaires and PSG monitoring, and could comply with study requirements for follow-up. Exclusion criteria were untreated physical disease; a previous history of epilepsy, depressive disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, neurodevelopmental delay, or cognitive disorder; shift workers; travel across three or more time zones within 14 days prior to enrollment; a previous history of other sleep disorders or PSG monitoring revealing the following conditions: sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome, apnea hypopnea index (AHI) >15 breaths/h, REM AHI (RAHI) >5 times/h; oxygen saturation <90%; periodic leg movement syndrome: periodic leg movement index (PLMI) >5 times/h; heterogeneous sleep. All subjects did not receive any psychological, physical, and/or pharmacological treatment between 7 days prior to admission and 3 months of follow-up.

We recorded baseline data on subjects' age, sex, body mass index, smoking, and alcohol consumption by telephone and clinic visits. After subjects were enrolled, psychological evaluations included the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (20), a 19-item questionnaire that assesses sleep quality and disorders over a 1-month interval. The first four items are open-ended questions, and items 5–19 are scored using a 4-point Likert scale. Scores for the seven components were obtained, and the scores were summed to obtain a total score ranging from 0 to 21. A score >5 indicates poor sleep quality. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (21), developed by 21, contains 21 self-administered anxiety questionnaires that reflect the severity of anxiety, and a BAI ≥45 is used as a criterion for positive anxiety. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (22) was developed by 22. The whole scale is divided into 21 groups, which are divided into 0–3 levels. After completing the sum of the parts, the total score was divided into four levels with total scores as follows: ≤ 10: healthy and no depression, 10–15: bad mood and attention, and 15–25: depression. A total score >25 indicates that depression is severe, and the patient must be seen by a psychiatrist. Subjects were followed up for 3 months, and then depression was assessed again using the BDI.

A trained psychometrician administered the questionnaire to the patients, informing them of the purpose of the study, the protocol, and precautions. The subject gave informed understanding and consent and then began to fill out the questionnaire. After completion of the questionnaire, the participant returned it, and the staff checked the completeness of the content.

Subjects who met the enrollment criteria underwent PSG within 1 week, and patients were given a sleep diary record to determine their resting patterns while waiting for PSG. The specific information of the polysomnograph used in the study is as follows: model and specification: Grael, medical device registration certificate number: 20172210823, manufacturer: Compumedics Limited. Sleep lab tests include one night of PSG monitoring. The PSG monitoring consists mainly of six leads of EEG activity (EEG: F3-M2, F4-M1, C3-M2, C4-M1, O1-M2, O2-M1), electromyographic activity of the jaw and tibialis anterior muscles (EMG), bilateral electro-ocular activity (EOG), electrocardiogram (ECG), oral and nasal airflow, chest and abdominal movements, oxygen saturation, and snoring. The measured parameters include stage REM sleep latency (RL): sleep onset to first epoch of Stage REM in minutes; number of REM sleep cycles (RC); total sleep time (TST) in minutes; REM sleep arousal index (REM-ArI): number of arousals in stage REM × 60/TST; NREM sleep arousal index (NREM-ArI): number of arousals in stage NREM × 60/TST; REM sleep duration (RD): time in stage REM; percentage of TST in stage REM (REM%): (time in stage REM/TST) × 100; percentage of TST in stage NREM (NREM%): (time in stage NREM/TST) × 100; and sleep efficiency (SE): (TST/time in bed) × 100. The installation of the PSG equipment and the analysis of the PSG were performed by professional PSG technicians under the technical guidance of a physician licensed as a registered PSG technician in the United States. The rules, terminology, and technical specifications of the American Association for Sleep Research Manual of Interpretation of Sleep and Associated Events version 2.6 (AASM) were used (23) as the interpretation criteria to determine sleep staging and sleep events.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0. Measured data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s), count data were expressed as percentages, mean values between groups were compared using independent samples t-test and chi-square (χ2) test, and Levene's homogeneity of variance test was used for independent samples t-test to test the difference in t-distribution of each index between two groups. If P > 0.05, there is a statistical difference. Both t-test and chi-square test (χ2) were used as two-sided tests, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson analysis was performed to analyze the correlation between multiple variables. Regression models were created using multiple linear regression, and their correlation was assessed using covariance diagnostics in linear regressions between multiple variables to determine whether these variables could be modeled. The Durbin-Watson (D-W) test was used to determine whether the independence conditions for linear regression were met. Analysis of variance was used to determine that the constructed regression model was statistically significant in the range of P < 0.05. Regression coefficients were used to indicate the degree of influence between the four constants of the REM arousal index, the number of REM cycles, REM latency, the number of REM arousals, and the dependent variable of depression score, and the regression coefficient P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

A total of 54 patients with SID were included, 28 (52%) of them were male and 26 (48%) were female. The mean age was (45.20 ± 13.92) years, and body mass index was (22.67 ± 2.73). The BDI score at admission was (6.17 ± 3.73). After 3 months of follow-up, BDI score was (10.07 ± 7.66); insomnia symptoms were relieved in 36 subjects and persisted in 18 subjects. Eleven of these patients (20%) had a BDI score >15, which implies 20% risk of depression in patients with SID after 3 months of follow-up. In the group with persistent insomnia symptoms, the probability of having a BDI score >15 was 50%, whereas in the group with recovery from SID, the probability of having a BID score >15 was only 6%. We define recovery from SID as subjects having 7 or more weeks of good sleep after an episode of SID at a 3-month follow-up, of which the last 4 weeks must be designated as good sleep. Good sleep: five or more nights per week requiring a sleep latency of 30 min or less with 5% TST or less time awake after sleep during the night. Total sleep duration is 6–10 h without daytime symptoms (19, 24).

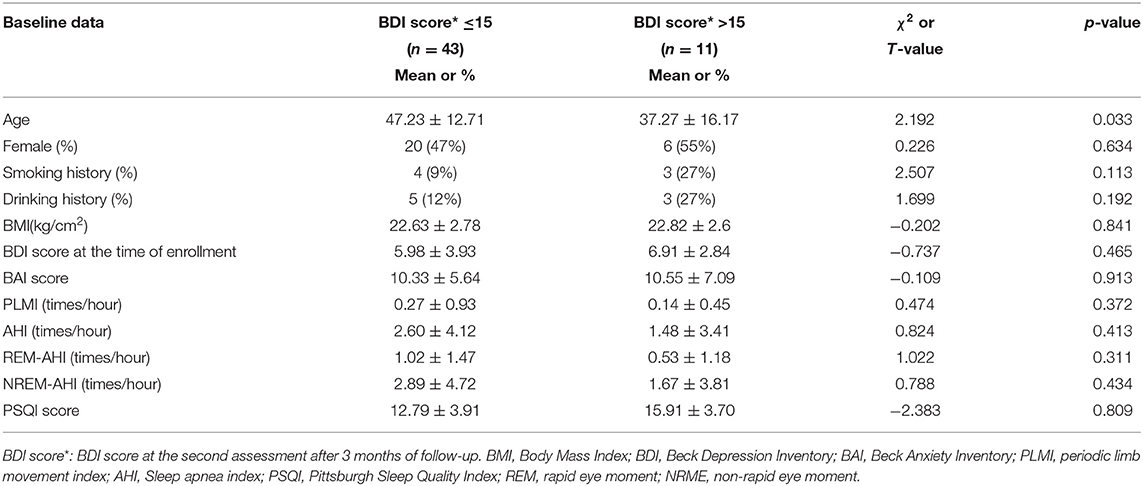

After 3 months of follow-up, the group was divided into SID with increased BDI score (BDI >15) and SID with normal BDI score (BDI ≤ 15) groups according to the BDI score of the second assessment. There was no statistical difference in baseline levels between the two groups except for age differences (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 54 SID patients (BDI score classification after 3 months of follow-up).

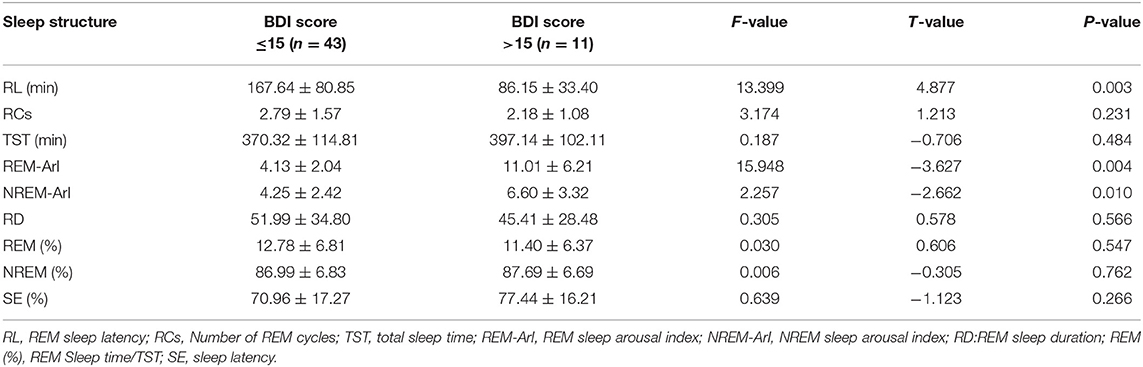

The statistical method of independent samples t-test was used to compare the differences between the two groups of indicators (Table 2): the REM sleep latency (t = 4.877, P = 0.003), the REM sleep arousal index (t = −3.627, P = 0.004) and the NREM sleep arousal index (t = −2.662, P = 0.010) with statistically significant differences.

Table 2. Independent sample t-test of sleep structure of the two groups of patients (BDI score classification after 3 months of follow-up).

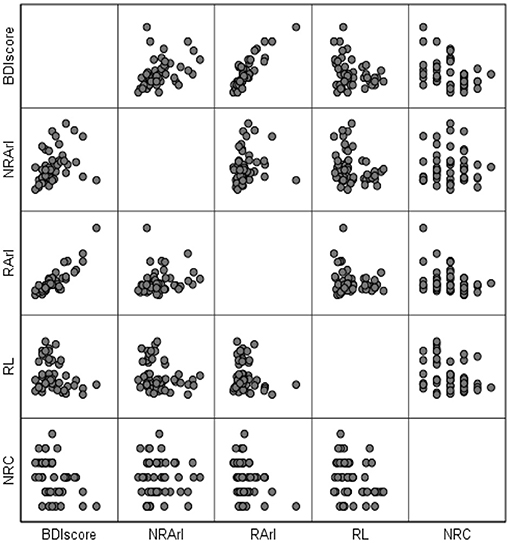

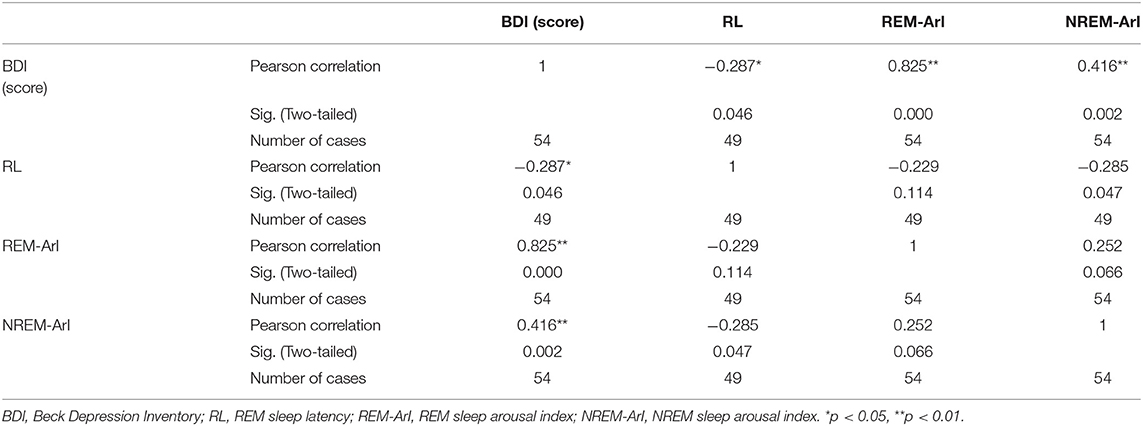

In linear regression and Pearson correlation analyses (Figure 1; Table 3), it is shown that the BDI score is positively correlated with the REM-ArI and NREM-ArI (significant at the 0.01 level, P = 0.000, P = 0.002) and negatively correlated with REM sleep latency (significant at the 0.05 level, P = 0.046).

Figure 1. Matrix scatterplot between BDI scores (after 3 months of follow-up) and structural variables of rapid eye movement sleep after 3 months of follow-up. BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; RL, REM sleep latency; REM-ArI, REM sleep arousal index; NREM-ArI, NREM sleep arousal index; RCs, Number of REM cycles.

Table 3. Correlation analysis between the BDI score and various indicators of sleep structure after 3 months of follow-up.

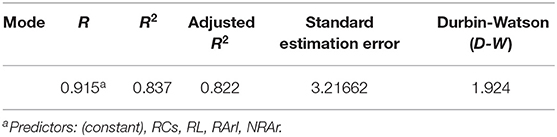

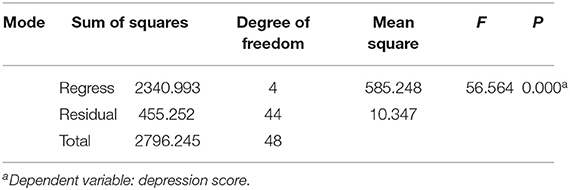

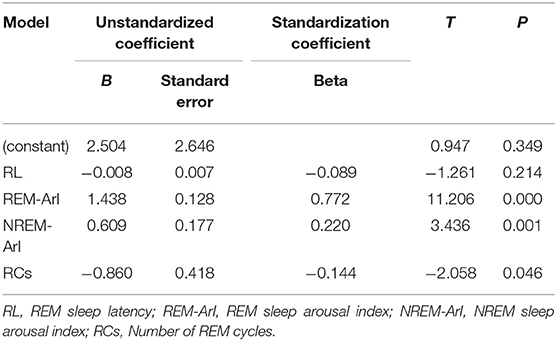

We constructed a regression model to further explore the relationship between REM sleep characteristics and BDI scores in patients with SID. Using the diagnosis of covariance in linear regression (Table 4), the correlation between multiple variables in this study was not significant. The D-W test value of 1.924 can be considered to satisfy the independence condition for linear regression. The results of the statistical tests of the model are presented in the analysis of variance (Table 5): the regression model (F = 56.564, p = 0.000 < 0.05), indicates that the constructed regression model is statistically significant. Therefore, a statistically significant model was constructed in this study, which had a good explanatory power (R2 = 0.837). The accuracy of the model in predicting the risk of depression was 83.7%. Table 6 shows the coefficients of the regression model used to predict the risk of depression in patients with SID: the standardized coefficient of the REM = ArI was β = 0.772, p = 0.000, indicating that the REM-ArI had the greatest effect on the risk of depression across the four variables.

Table 4. Summary of regression models for predicting the risk of depression in patients with short-term insomnia.

Table 5. Analysis of variance of the regression model for predicting the risk of depression in patients with short-term insomnia.

Table 6. Predictive regression model coefficients of depression risk in patients with short-term insomnia.

The challenge of the link between insomnia and depression is that insomnia disorder may be both a risk factor for and a consequence of depression. The comorbidity of depression and insomnia disorder did not first attract the attention of researchers, and at first, attention was focused on the latter proposition: that insomnia was a clinical symptom accompanying depressive disorders and that insomnia symptoms would resolve with improvement of depressive symptoms as long as we treated them with antidepressant therapy. Until the early 1990s, several studies showed that preexisting or persistent insomnia symptoms not only failed to resolve with improvement in depressive symptom but instead, increased the risk of depressive episodes and were a risk factor for depressive disorders (25, 26). Therefore, one of our aims in this study was to investigate whether the presence or persistence of insomnia symptoms increases the risk of depressive episodes. By measuring depression in 54 patients with SID using the BDI depression scale, it was found that the probability of having a BDI score >15 was found to be 50% in the group with persistent insomnia symptoms after 3 months of follow-up, and the probability of having a BID score >15 was only 6% in the group with remission of insomnia symptoms. This result suggests that patients with persistent insomnia symptoms are more likely to experience depressive mood. Insomnia is an important marker of depression, which is consistent with the results of many foreign studies (5, 6, 27).

Although we observed that the chronic presence of insomnia symptoms is a risk factor for the development of depression, no studies have been able to explain the specific mechanisms underlying the association between insomnia and depression, and there is a lack of corresponding physiological features or biological characteristics that can predict the risk of depression (28). The quantitative electroencephalogram (EEG) studies show that there are characteristic changes in depression, consisting of disturbed sleep continuity, inductions of REM sleep. Of all the changes, abnormalities in REM sleep are key to the EEG changes in depression (29). It was shown as early as 2009 that REM sleep facilitates the reactivation of previously acquired emotional experiences in the limbic system of the brain and their integration with semantic memory, leading to a decrease in amygdala activity and traces of emotional memory over time (30). This finding suggests that changes in the structure of REM sleep results in blocked reactivation of previously acquired emotional experiences in the limbic system of the brain, leading to diminished amygdala activity and elimination of traces of emotional memory. Studies on how eye movements in REM sleep cause transient, time-specific activation of the amygdala also confirm the role of the limbic system in the reprocessing and consolidation of emotional experiences in REM sleep (12). As observed through several studies (13): changes in the structure of REM sleep, such as shortened REM latency, increased REM sleep duration, and increased density of REM, are frequently observed in people diagnosed with depressive disorders.

Recently, it was found that depression may be related to the dysfunction of a network of structures that regulate REM sleep, such as the limbic system, including the hippocampus, amygdala, and medial pre-frontal cortex. The reward network is dysfunctional and associated with depression symptoms in patients with chronic insomnia disorder (31). Furthermore, the subregions of the medial pre-frontal cortex (mPFC) show great changes in neural activity in depressed patients (32). Anatomic tracing studies show that the mPFC projects to the pontine REM-off neurons in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray and adjacent lateral pontine tegmentum, which interacts with REM-on neurons in the dorsal pons. Therefore, the ventral mPFC may be a critical area for regulating both depression and sleep, and it is suggested as a critical site for REM sleep abnormalities and other behaviors in depression (33). Depression is reported to be associated with a reduction in 5-hydroxytryptamine neurotransmission, which may explain why depression is characterized by a short REM sleep latency (the 5-hydroxytryptamine system is off-line during REM sleep). That said, the role of 5-hydroxytryptamine neurotransmission between insomnia and depression may be much more complex and may be better characterized by an overall dysregulation of the system (i.e., the system is online when it should be off-line and off-line when it should be online) (28, 34).

Expanding upon traditional ways of looking at REM alterations, recent studies examine REM sleep fragmentation (i.e., the number and duration of short arousals that disrupt the continuity of the REM period). Thus, REM sleep continuity may function to depotentiate emotional load: a function that is disrupted when REM is fragmented by brief arousals (13, 35). The possibility exists that REM sleep fragmentation is linked with less efficient regulation of negative affect. The results of our study found that 54 patients with SID were divided into SID with increased BDI score (BDI >15) and SID with normal BDI score (BDI ≤ 15), and the total BDI score was positively correlated with REM-ArI and NREM-ArI and negatively correlated with REM sleep latency after a 3-month follow-up observation. This structural sleep characteristic could suggest that the presence of shortened REM latency and REM sleep fragmentation (increased microarousal index) in patients with clinical insomnia disorder would increase the risk of depressive episodes. We further developed a regression model to predict the risk of depression to explore the relationship between REM sleep characteristics and depression in patients with SID. The model uses four independent variables, REM-ArI, REM cycle number, REM sleep latency, and NREM-ArI, to predict the risk of subsequent depression with 83.7% accuracy. Further analysis of the regression coefficients revealed that their REM-ArI had the greatest effect on depression. The results suggest that REM sleep fragmentation has an extremely important role in depressive mood changes, there are relatively few studies on specific REM structural characteristics in previous studies, and the study of the relationship between changes in REM structure and depressive mood may further refine the explanation and description of the mechanism that there are many studies reporting that insomnia disorder increases the risk of depressive episodes.

This may also indirectly suggest that insomnia may act on emotion regulation mechanisms by disrupting the structure of REM sleep, thus affecting the reprocessing and consolidation of emotions and leading to a weakening of the effect of eliminating negative emotions. Excessive arousal and REM sleep fragmentation play an important role in emotion regulation in insomnia, depression, and PTSD by affecting the elimination of negative emotions (36). Our study suggests that changes in the structure of REM sleep, especially REM sleep fragmentation, may be a characteristic marker for assessing the risk of depressive episodes and that these patients with short-term insomnia disorders presenting with REM sleep fragmention should be alerted to appropriate interventions to reduce the risk of developing depression.

Our study used primarily one night of sleep monitoring data, and therefore, there is some controversy as to whether the results are affected by first-night effects. Although several previous studies show no statistical difference in sleep structure data between subjects on the first and second night (37–39). Another limitation of the study is that in the present study, we mainly assessed depression levels using the BDI scale in patients with SID with a 3-month follow-up without further clarifying the diagnosis according to the diagnostic criteria of depression.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Ningbo First Hospital (No. 2018-R048). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

DW: conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, writing-original draft, visualization, investigation, and formal analysis. MT: writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, investigation, and validation. YJ: validation, investigation, and supervision. LR: project administration and validation. ZL: data curation and visualization. HG: investigation and formal analysis. QY: resources and investigation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by Medicine and Health Technology Plan Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2019RC261), Research Fund of traditional Chinese medicine in Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2018ZB116), Medicine and Health Technology Plan Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2017KY136), and Major Social Development Special Foundation of Ningbo (Grant No. 2017C510010).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Mai E, Buysse DJ. Insomnia: prevalence, impact, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Sleep Med Clin. (2008) 3:167–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2008.02.001

2. Spiegelhalder K, Regen W, Nanovska S, Baglioni C, Riemann D. Comorbid sleep disorders in neuropsychiatric disorders across the life cycle. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2013) 15:364. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0364-5

3. Patel D, Steinberg J, Patel P. Insomnia in the elderly: a review. J Clin Sleep Med. (2018) 14:1017–24. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7172

4. Hertenstein E, Feige B, Gmeiner T, Kienzler C, Spiegelhalder K, Johann A, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2019) 43:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006

5. Wei Y, Colombo MA, Ramautar JR, Blanken TF, Werf YD, Spiegelhalder K, et al. Sleep stage transition dynamics reveal specific stage 2 vulnerability in insomnia. Sleep. (2017) 40:1–10. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx117

6. Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Price JC, Miewald JM, Kupfer DJ. Functional neuroimaging evidence for hyperarousal in insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. (2004) 161:2126–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2126

7. Cano G, Mochizuki T, Saper CB. Neural circuitry of stress-induced insomnia in rats. J Neurosci. (2008) 8:10167–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1809-08.2008

8. Kay DB, Karim HT, Soehner AM, Hasler BP, Wilckens KA, James JA, et al. Sleep-wake differences in relative regional cerebral metabolic rate for glucose among patients with insomnia compared with good sleepers. Sleep. (2016) 39:1779–94. doi: 10.5665/sleep.6154

9. Feige B, Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K. The microstructure of sleep in primary insomnia: an overview and extension. Int J Psychophysiol. (2013) 89:171–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.04.002

10. Pérusse AD, Pedneault-Drolet M, Rancourt C, Turcotte I, St-Jean G, Bastien CH. REM sleep as a potential indicator of hyperarousal in psychophysiological and paradoxical insomnia sufferers. Int J Psychophysio. (2015) 195:372–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.01.005

11. Wassing R, Benjamin JS, Dekker K. Slow dissolving of emotional distress contributes to hyperarousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:2538–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522520113

12. Corsi-Cabrera M, Velasco F, Río-Portilla YD, Armony JL, Trejo-Martínez D, Guevara MA, et al. Human amygdala activation during rapid eye movements of rapid eye movement sleep: an intracranial study. J Sleep Res. (2016) 25:576–82. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12415

13. Pesonen AK, Gradisar M, Kuula L, Short M, Merikanto I, Tark R, et al. REM sleep fragmentation associated with depressive symptoms and genetic risk for depression in a community-based sample of adolescents. J Affect Disord. (2019) 245:757–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.077

14. Gilson M, Deliens G, Leproult R, Bodart A, Nonclercq A, Ercek R, et al. REM-Enriched naps are associated with memory consolidation for sad stories and enhance mood-related reactivity. Brain Sci. (2015) 6:1. doi: 10.3390/brainsci6010001

15. Riemann D, Krone LB, Wulff K, Nissen C. Sleep, insomnia, and depression. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2012) 45:167–76. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299721

16. Goldstein AN, Walker MP. The role of sleep in emotional brain function. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2014) 10:679–708. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153716

17. Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. (2011) 135:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011

18. Li LQ, Wu CM, Gan Y, Qu XG, Lu Z, Insomnia X and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:375. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1075-3

19. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders-Third Edition. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2014).

20. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

21. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1988) 56:893–7. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893

22. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation (1996). doi: 10.1037/t00742-000

23. Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, Berry HSM, Lloyd RM, Marcus CL, et al. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. VERSION 2.3. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2017).

24. Perlis ML, Vargas I, Ellis JG, Grandner MA, Morales KH, Gencarelli A, et al. The Natural History of Insomnia: the incidence of acute insomnia and subsequent progression to chronic insomnia or recovery in good sleeper subjects. Sleep J. (2020) 43:1–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz299

25. Riemann D, Krone LB, Wulff K, Nissen C. Sleep, insomnia, and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2020) 45:74–89. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0411-y

26. Victor R, Garg S, Gupta R. Insomnia and depression: how much is the overlap? Indian J Psychiatry. (2020) 6:623–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_461_18

27. Rouquette A, Pingault JB, Fried EI, Orri M, Falissard B, Kossakowski JJ, et al. Emotional and behavioral symptom network structure in elementary school girls and association with anxiety disorders and depression in adolescence and early adulthood: a network analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. (2018) 75:1173–81. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2119

28. Vargas I, Perlis ML. Insomnia and depression: clinical associations and possible mechanistic links-Science Direct. Curr Opin Psychol. (2020) 34:95–9. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.11.004

29. Steiger A, Kimura M. Wake and sleep EEG provide biomarkers in depression. J Psychiatr Res. (2010) 44:242–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.08.013

30. Walker MP, van der Helm E. Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychol Bull. (2009) 135:731–48. doi: 10.1037/a0016570

31. Gong L, Yu SY, Xu RH, Liu D, Dai XJ, Wang ZY, et al. The abnormal reward network associated with insomnia severity and depression in chronic insomnia disorder. Brain Imaging Behav. (2020) 15:1033–42. doi: 10.1007/s11682-020-00310-w

32. Wang YQ, Li R, Zhang MQ, Zhang Z, Qu WM, Huang ZL. The neurobiological mechanisms and treatments of rem sleep disturbances in depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2015) 13:543–53. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666150310002540

33. Chang CH, Chen MC, Qiu MH, Lu J. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex regulates depressive-like behavior and rapid eye movement sleep in the rat. Neuropharmacology. (2014) 86:125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.07.005

35. Habukawa M, Uchimura N, Maeda M, Ogi K, Hiejima H, Kakuma T. Differences in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep abnormalities between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder patients: REM interruption correlated with nightmare complaints in PTSD. Sleep Med. (2018) 43:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.10.012

36. Bottary R, Seo J, Daffre C, Gazecki S, Moore KN, Kopotiyenko K, et al. Fear extinction memory is negatively associated with REM sleep in insomnia disorder. Sleep J. (2020) 43:1–2. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa007

37. Moser D, Kloesch G, Fischmeister F, Bauer H, Zeitlhofer J. Cyclic alternating pattern and sleep quality in healthy subjects—is there a first-night effect on different approaches of sleep quality? Biol Psychol. (2010) 83:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.09.009

38. Gaines J, Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Basta M, Pejovic S, He F, et al. Short- and long-term sleep stability in insomniacs and healthy controls. Sleep. (2015) 38:1727–34. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5152

Keywords: polysomnography, REM fragmentation, acute insomnia, sleep arousal, depression

Citation: Wu D, Tong M, Ji Y, Ruan L, Lou Z, Gao H and Yang Q (2021) REM Sleep Fragmentation in Patients With Short-Term Insomnia Is Associated With Higher BDI Scores. Front. Psychiatry 12:733998. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.733998

Received: 30 June 2021; Accepted: 05 August 2021;

Published: 09 September 2021.

Edited by:

Bin Zhang, Southern Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Xinhua Shen, Third People's Hospital of Huzhou, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Wu, Tong, Ji, Ruan, Lou, Gao and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maoqing Tong, bmluZ2JvZHl5eUAxNjMuY29t; Yunxin Ji, amFuZWdlZ2VfMTIzQDE2My5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.