94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Psychiatry, 14 September 2021

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.713987

Hossein Akbarialiabad1,2

Hossein Akbarialiabad1,2 Bahar Bastani3

Bahar Bastani3 Mohammad Hossein Taghrir4

Mohammad Hossein Taghrir4 Shahram Paydar4

Shahram Paydar4 Nasrollah Ghahramani5

Nasrollah Ghahramani5 Manasi Kumar6,7*

Manasi Kumar6,7*The new era of digitalized knowledge and information technology (IT) has improved efficiency in all medical fields, and digital health solutions are becoming the norm. There has also been an upsurge in utilizing digital solutions during the COVID-19 pandemic to address the unmet mental healthcare needs, especially for those unable to afford in-person office-based therapy sessions or those living in remote rural areas with limited access to mental healthcare providers. Despite these benefits, there are significant concerns regarding the widespread use of such technologies in the healthcare system. A few of those concerns are a potential breach in the patients' privacy, confidentiality, and the agency of patients being at risk of getting used for marketing or data harnessing purposes. Digital phenotyping aims to detect and categorize an individual's behavior, activities, interests, and psychological features to properly customize future communications or mental care for that individual. Neuromarketing seeks to investigate an individual's neuronal response(s) (cortical and subcortical autonomic) characteristics and uses this data to direct the person into purchasing merchandise of interest, or shaping individual's opinion in consumer, social or political decision making, etc. This commentary's primary concern is the intersection of these two concepts that would be an inevitable threat, more so, in the post-COVID era when disparities would be exaggerated globally. We also addressed the potential “dark web” applications in this intersection, worsening the crisis. We intend to raise attention toward this new threat, as the impacts might be more damming in low-income settings or/with vulnerable populations. Legal, health ethics, and government regulatory processes looking at broader impacts of digital marketing need to be in place.

Globally stigma, gender-, cultural-, racial insensitivities, and discrimination are some of the systemic barriers in optimally scaling up mental health care (1). Digital tools have the potential to ease these barriers by making mental health services accessible to all; more importantly to remote, needier, and vulnerable populations. Digital solutions offer more choices to patients and service users. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, digital health and telehealth services have expanded tremendously to meet the rising demands (2–5). Using such technologies has improved freedom, efficacy, and flexibility in communication for patients and physicians worldwide. On the flip side, several studies have shown that digital mental health applications may alienate some and raise anxiety and stress for some clients, including fear of relapse and even paranoid thinking (6–9). Concerns that continue to remain unaddressed include breach of patients' privacy, confidentiality, autonomy, and undermining of patients' agency by using patient data for other purposes than they consented for (10). The rapid albeit heedless use of digital tools has introduced a substantial threat. There is a relative lack of proper legislation and practical safeguards to protect patients' personal information in general and more so in emerging economies (11). We underscore the emergence of a potentially serious threat to individuals and communities at large arising from the intersecting impact of rapid “digital phenotyping” and “digital neuromarketing” globally. This commentary collectively highlights how this unregulated practice may adversely impact under-resourced contexts where patient interests may be cast aside to serve big data for commercial gains.

Digital phenotyping aims to detect individual behavior, activities, interests, and physiological features to utilize the information to customize the care (12). A few examples are: tracking the digital biomarkers like locations, accelerometer, social communication, screen lock/unlock events, call logs, camera events, use of particular app(s), browser history, light sensor, sleep-wake cycle, exercise, and social interactions through the smartwatches/phones (13). Digital phenotyping applications have been utilized in detecting and intervening in a wide range of psychiatric disorders, from mood and anxiety disorders to drug abuse and suicidal thoughts (14–21). Recently, sensing technologies have yielded a wide range of usage in detecting and predicting the psychological and psychiatric conditions. Using heart rate variability (HRV) by multilayer perception model, skin conductance (SC) method, and long short-term memory neural network models (LSTM) are the commonest ways currently used for detecting and predicting the stress level through biosensors (22). Apart from sensors, other minor aspects of smartphones such as the average number of daily calls and text messages, average time spending on social media and entertainment applications, and the average time of web browsing have been shown to be able to detect and predict the severity of depression with high accuracy (23). However, alongside the competitive advantage of offering appropriate customized services, digital phenotyping intrinsically impacts what it is to be a human person and potentially undermines human-human interaction as emanating from a therapeutic/clinical consultation where two individuals (at times more) connect deeply to address highly intricate and complex problems (24–27).

Neuromarketing, too, has similarly attracted significant academic and commercial interest (28). It develops tools to capture the unspoken feelings/emotions, desires, and cognition of the consumers to various marketing stimuli to foresee personal decisions, such as purchasing decisions. The neuromarketing studies took advantage of the advances in the neurosciences, and while in the beginning, they were more focused on neuroimaging, encompassing functional brain MRI (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG), lately the field has turned to tapping into autonomic nervous system to enhance targeted marketing using biofeedback mechanisms (29). For example, using digital neuromarketing, Cerf and colleagues predicted the future sale of a movie by measuring the engagement of a sample population while simultaneously looking to their EEGs by around 20% better comparing to the traditional methods (30, 31); Moreover, there are multiple other real world implications of neuromarketing are available (32, 33). Furthermore, neuromarketing research has recently turned to detecting clients' physiologic responses, such as heart rate changes, eye tracking, galvanic cutaneous reactions, and developing facial action coding systems, with or without utilizing brain signal recording techniques gauging occult clients' reactions (30). Digital neuromarketing is quite different from traditional marketing tools since it bypasses the clients' thinking processes and directly captures the response of the clients' nervous systems (34). The market of global neuromarketing is by no mean negligible; the market was valued 1.158 billion US dollar in 2020 and projected to be 1.896 billion dollar in 2026 (35).

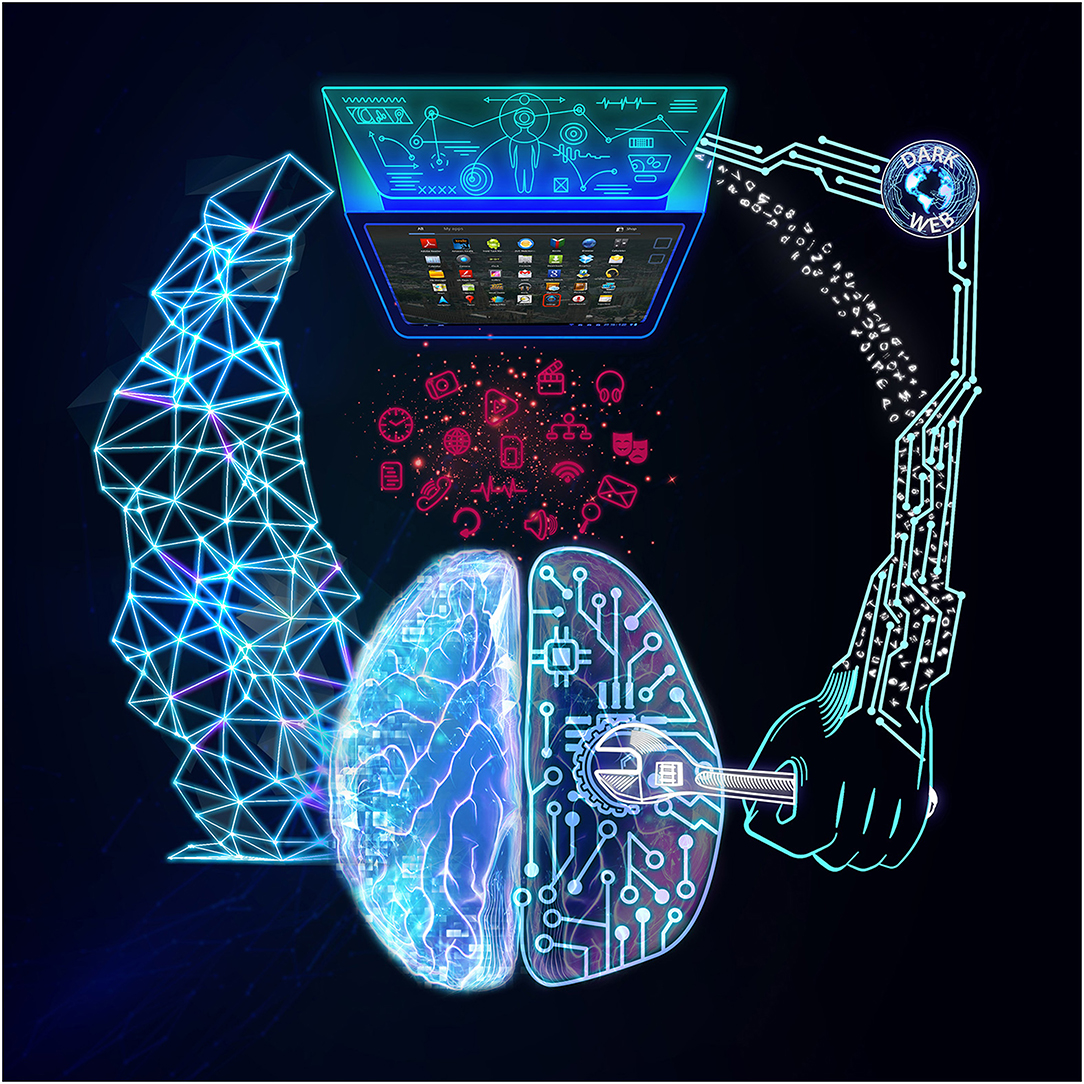

The intersection of digital phenotyping and digital neuromarketing can be perilous and could potentially lead to what we may call “digital surveillance capitalism” in Figure 1. The former recognizes human preferences from the “inside” via multiple bodily sensors that may be out of our control, such as our heartbeat and other autonomic responses. The latter analyzes the input and directs us toward shopping for particular goods, voting for a particular candidate, or may steer us to a specific brand name. This kind of behavioral targeting also influences our concepts of free will, democracy, and our human agency in the long term. Moreover, targeting those with sub-optimal ability to control their impulses and interests, such as children and adolescents, could make this issue even more complicated. It can become even more complicated with integrating personal health information from the dark web as an illegal but potent data source (36). The dark web is a part of the interconnected network (internet) that requires specific softwares and configurations to access, where many illicit transactions of drugs, human organs, weapons, and data trade occur (37). For example, in 2016, health-related documents, including the family history of about 16 million individuals, were sold in the internet's black market (dark web) around 20-50$ (38). By Looking to this illegal data sharing and multiple similar uses of the dark web (39, 40), the undesireable kind of connection between digital neuromarketing and digital phenotyping would be strengthened (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Digital Surveillance Capitalism. On the left, you see the potentially beneficial digital phenotyping, where clients' or patients' information are collected through their apps to better serve them. On the right, you see the potentially unintended consequences of the intersection of digital phenotyping, dark web, and digital neuromarketing where profiteers may use the collected personal information for their illegal and unethical financial gain. The figure also shows the bidirectional nature of these communications; such that, the dark web that is fed by digital phenotyping and digital neuromarketing; meanwhile, can simultaneously strengthen their hazardous impact.

To further clarify this menacing intersection, imagine a giant technology company or government agency accessing the individuals' digital phenotyping and neuromarketing data. This could potentially enable them to influence and manipulate a populations' emotions and collective external behavior. For example, prior to an election, they could present a seemingly casual political advertisement on their smartphone (digital neuromarketing). The population's reaction to these advertisements would subsequently be analyzed using digital biomarkers, such as a heartbeat change as a sign of satisfaction or disgust and anger (digital phenotyping). The next step would be to reinforce positive emotions toward the desired candidate and promote negative feelings toward the undesired candidate by targeting the individuals at the time of their relaxation and happiness with positive and relaxing ads supporting the desired candidate. Vise versa, during stressful moments, presenting them with negative advertisements against the undesired political candidate. Such scenarios would favor the emergence of powerful totalitarian governments that could control and shape the populations' external behavior based on their intrinsic reactions to targeted stimuli. A similar scenario could be extended to a big pharmaceutical company directing physicians and patients into a desired pharmaceutical choice, which would go on in many other contexts.

We believe that while digital phenotyping and digital neuromarketing will unravel many unknown frontiers of neuroscience and mental health, their intersection would act as a double-edged sword and bring serious mental health concerns to individuals, such as invasion of privacy, decrease in self-confidence, and use of unhealthy monitoring through digital phenotyping into mental health care programs. The following recommendations may be needed to be put in place to help reduce the unintended consequences.

- Technical and Public Evaluation of technologies and media before release: These advanced technologies should be rigorously studied and critically evaluated before their widespread implementation to maximize their benefits and minimize the potential misuse in the hands of profiteers. More rigorous, well-defined regulations and guidelines are urgently needed to protect the public from those who wish to exploit them for their financial or political gain. As an example, a single company has been penalized several times for privacy issues, the current regulations and laws seem unworkable (41–43). Besides, there are several technical methods to maintain the patients' and users' privacy. In parallel with using blockchain technology (44, 45), differential privacy algorithms are the most efficient methods currently utilized in this regard by creating random noise to sensitive data. In addition, other methods are also important; for instance, blurring face of bystanders and real-time processing locally to prevent the harms of data sharing with third parties (46). Also, “white hat hackers,” ethical professional hackers who use their knowledge and competency to find digital systems' vulnerability for good purposes (47), could play a significant role in evaluating apps that claim they do not collect and use this kind of information.

- Regulatory processes in place with careful monitoring: Independent mentoring and regulatory organizations should vigorously investigate abuses of these high technology tools, particularly digital phenotyping and neuromarketing, to protect the public from unethical practices. As suggested by multiple recent United Nations' documents and meetings (48, 49), establishing international collaborations and ethical committees to supervise and monitor digital tools' activity would be beneficial (44).

- Transparency as a policy measure: Each digital tool's ‘terms and policy' should clearly state that the applications may analyze the users' data and behavior for commercial intents as a separate item to be approved. It should be considered a crime if a company uses the consumers' data without their permission or without clearly explaining it to them, as this is a clear violation of consumers' right to privacy.

- Public awareness and Education on apps: The public should be educated on the benefits and the harms of using telehealth apps. Public health programs, NGOs, and human rights activists should take action on this. This is of more importance for those living in developing countries as they are at higher risk of being exploited in such unregulated intersections. Education should be contextual and need-based; thus, digital mental health and its related ethical considerations should be incorporated into the curriculum of mental health trainings to start this discussion early on with learners at all levels.

- Taxing the information gathering: Information is one of the most invaluable assets. Similar to property tax, we suggest information tax for giant companies to modulate the current inappropriate global trend toward compiling big data of the consumers. The notion of imposing such taxes will certainly draw the attention of politicians and policymakers to this important issue. We suggest such taxes be used for public education toward sustainable and ethical e-health solutions towards strengthening the health care system in low-resource settings.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

HA conceived the concept and wrote the initial draft. All authors contributed to the evolving, editing, and revising of this paper and approved the final draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to express their great appreciation to Dr. Sima Roushenas, Dr. Parimah Shahravan, and Dr. Amin Feili for the figure's conceptualization. We also acknowledge Dr. Joseph Charles Kvedar, M.D. for his dedicated and kind support in developing this concept.

1. Crumb L, Mingo TM, Crowe A. “Get over it and move on”: The impact of mental illness stigma in rural, low-income United States populations. Mental Health & Prevention. (2019) 13:143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mhp.2019.01.010

2. Tang S, Helmeste D. Digital psychiatry. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2000) 54:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2000.00628.x

3. Balcombe L, De Leo D. An integrated blueprint for digital mental health services amidst COVID-19. JMIR mental health. (2020) 7:e21718. doi: 10.2196/21718

4. Kola L. Global mental health and COVID-19. The Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:655–7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30235-2

5. Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. (2020) 395:1180–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7

6. Eisner E, Bucci S, Berry N, Emsley R, Barrowclough C, Drake RJ. Feasibility of using a smartphone app to assess early signs, basic symptoms and psychotic symptoms over six months: a preliminary report. Schizophr Res. (2019) 208:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.04.003

7. Eisner E, Drake RJ, Berry N, Barrowclough C, Emsley R, Machin M, et al. Development and long-term acceptability of ExPRESS, a mobile phone app to monitor basic symptoms and early signs of psychosis relapse. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. (2019) 7:e11568. doi: 10.2196/11568

8. Ben-Zeev D, Scherer EA, Gottlieb JD, Rotondi AJ, Brunette MF, Achtyes ED, et al. mHealth for schizophrenia: patient engagement with a mobile phone intervention following hospital discharge. JMIR mental health. (2016) 3:e6348. doi: 10.2196/mental.6348

9. Bradstreet S, Allan S, Gumley A. Adverse event monitoring in mHealth for psychosis interventions provides an important opportunity for learning. J Mental Health. (2019) 28:461–6. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2019.1630727

10. Parker L, Bero L, Gillies D, Raven M, Mintzes B, Jureidini J, et al. Mental health messages in prominent mental health apps. Ann Family Med. (2018) 16:338–42. doi: 10.1370/afm.2260

11. Larsen ME, Huckvale K, Nicholas J, Torous J, Birrell L, Li E, et al. Using science to sell apps: evaluation of mental health app store quality claims. NPJ Dig Med. (2019) 2:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0093-1

12. Jain SH, Powers BW, Hawkins JB, Brownstein JS. The digital phenotype. Nat Biotechnol. (2015) 33:462–3. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3223

13. Melcher J, Hays R, Torous J. Digital phenotyping for mental health of college students: a clinical review. Evid Based Ment Health. (2020) 23:161–6. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2020-300180

14. Barnett I, Torous J, Staples P, Sandoval L, Keshavan M, Onnela JP. Relapse prediction in schizophrenia through digital phenotyping: a pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2018) 43:1660–6. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0030-z

15. Henson P, Barnett I, Keshavan M, Torous J. Towards clinically actionable digital phenotyping targets in schizophrenia. npj Schizophrenia. (2020) 6:13. doi: 10.1038/s41537-020-0100-1

16. Nandakumar R, Gollakota S, Sunshine JE. Opioid overdose detection using smartphones. Sci Trans Med. (2019) 11:1–10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau8914

17. Jacobson NC, Weingarden H, Wilhelm S. Using digital phenotyping to accurately detect depression severity. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2019) 207:893–6. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001042

18. Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Beale EE, Picard RW, Huffman JC, et al. Digital phenotyping of suicidal thoughts. Depress Anxiety. (2018) 35:601–8. doi: 10.1002/da.22730

19. Jacobson NC, Summers B, Wilhelm S. Digital biomarkers of social anxiety severity: digital phenotyping using passive smartphone sensors. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e16875. doi: 10.2196/16875

20. Byrnes HF, Miller BA, Wiebe DJ, Morrison CN, Remer LG, Wiehe SE. Tracking adolescents with global positioning system-enabled cell phones to study contextual exposures and alcohol and marijuana use: a pilot study. Journal of Adolescent Health. (2015) 57:245–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.013

21. Hahn L, Eickhoff SB, Habel U, Stickeler E, Schnakenberg P, Goecke TW, et al. Early identification of postpartum depression using demographic, clinical, and digital phenotyping. Transl Psychiatry. (2021) 11:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01245-6

22. Ueafuea K, Boonnag C, Sudhawiyangkul T, Leelaarporn P, Gulistan A, Chen W, et al. Potential applications of mobile and wearable devices for psychological support during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. IEEE Sens J. (2020) 21:7162–78. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2020.3046259

23. Razavi R, Gharipour A, Gharipour M. Depression screening using mobile phone usage metadata: a machine learning approach. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2020) 27:522–30. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz221

24. Stanghellini G, Leoni F. Digital phenotyping: ethical issues, opportunities, and threats. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:473. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00473

25. Onnela J-P, Rauch SL. Harnessing smartphone-based digital phenotyping to enhance behavioral and mental health. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2016) 41:1691–6. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.7

26. Char DS, Shah NH, Magnus D. Implementing machine learning in health care—addressing ethical challenges. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:981. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1714229

27. Cosgrove L, Karter JM, Morrill Z, McGinley M. Psychology and surveillance capitalism: the risk of pushing mental health apps during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Humanistic Psychol. (2020) 60:611–25. doi: 10.1177/0022167820937498

28. Spence C. Neuroscience-inspired design: From academic neuromarketing to commercially relevant research. Organ Res Methods. (2019) 22:275–98. doi: 10.1177/1094428116672003

29. Ariely D, Berns GS. Neuromarketing: the hope and hype of neuroimaging in business. Nature reviews neuroscience. (2010) 11:284–92. doi: 10.1038/nrn2795

31. Barnett SB, Cerf MA. ticket for your thoughts: method for predicting content recall and sales using neural similarity of moviegoers. J Consumer Res. (2017) 44:160–81. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucw083

32. Recent Neuromarketing Research Studies (and Their Real-World Takeaways). Available online at: https://cxl.com/blog/neuromarketing-research/. (accessed August11, 2021).

33. How Neuromarketing Can Revolutionize the Marketing Industry [+Examples]. Available online at: https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/neuromarketing. (accessed August 10, 2021).

34. Rawnaque FS, Rahman KM, Anwar SF, Vaidyanathan R, Chau T, Sarker F, et al. Technological advancements and opportunities in Neuromarketing: a systematic review. Brain Inform. (2020) 7:1–19. doi: 10.1186/s40708-020-00109-x

35. Neuromarketing Market - Growth Trends COVID-19 Impact and Forecasts (2021 - 2026). Available online at: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/neuromarketing-market. (accesed August 11, 2021).

36. Akbarialiabad H, Dalfardi B, Bastani B. The double-edged sword of the dark web: its implications for medicine and society. J Gen Intern Med. (2020) 35:3346–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05911-1

37. Li Z, Du X, Liao X, Jiang X, Champagne-Langabeer T. Demystifying the dark web opioid trade: content analysis on anonymous market listings and forum posts. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e24486. doi: 10.2196/24486

38. Conaty-Buck S. Cybersecurity and healthcare records. Am Nurse Today. (2017) 12:62–4. Available online at: https://www.myamericannurse.com/cybersecurity-healthcare-records/ (accessed August 28, 2021).

39. Bracci A, Nadini M, Aliapoulios M, McCoy D, Gray I, Teytelboym A, et al. Dark Web Marketplaces and COVID-19: before the vaccine. EPJ data science. (2021) 10:6. doi: 10.1140/epjds/s13688-021-00259-w

40. MacIntyre CR, Engells TE, Scotch M, Heslop DJ, Gumel AB, Poste G, et al. Converging and emerging threats to health security. Environ Syst Decis. (2018) 38:198–207. doi: 10.1007/s10669-017-9667-0

41. Cardoso R. Antitrust: Commission fines Google e2.42 billion for abusing dominance as search engine by giving illegal advantage to own comparison shopping service: European Commission. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_1784. (accessed June 27, 2017)

42. Stempel J. Google faces $5 billion lawsuit in U.S. for tracking 'private' internet use: Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-alphabet-google-privacy-lawsuit-idUSKBN23933H. (accessed June 3, 2020).

43. Keshner A. Supreme Court sends consumers suing Google over privacy issues back to court: Market Watch. Available online at: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/supreme-court-sends-consumers-suing-google-over-privacy-issues-back-to-court-2019-03-20. (accessed March 20, 2019)

44. Roman-Belmonte JM, De la Corte-Rodriguez H, Rodriguez-Merchan EC. How blockchain technology can change medicine. Postgraduate Med. (2018) 130:420–7. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2018.1472996

45. Radanović I, Likić R. Opportunities for use of blockchain technology in medicine. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2018) 16:583–90. doi: 10.1007/s40258-018-0412-8

46. Leelaarporn P, Wachiraphan P, Kaewlee T, Udsa T, Chaisaen R, Choksatchawathi T, et al. Sensor-driven achieving of smart living: a review. IEEE Sens J. (2021). doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2021.3059304

47. Caldwell T. Ethical hackers: putting on the white hat. Netw Secur. (2011) 2011:10–3. doi: 10.1016/S1353-4858(11)70075-7

48. Global cooperation and regulation key in addressing multilayered threats posed by new technology. United Nations (UN). (accessed August 11 2021).

Keywords: digital phenotyping, digital neuromarketing, global mental health, data privacy, digital mental health regulations, lower and middle income counteries

Citation: Akbarialiabad H, Bastani B, Taghrir MH, Paydar S, Ghahramani N and Kumar M (2021) Threats to Global Mental Health From Unregulated Digital Phenotyping and Neuromarketing: Recommendations for COVID-19 Era and Beyond. Front. Psychiatry 12:713987. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.713987

Received: 24 May 2021; Accepted: 23 August 2021;

Published: 14 September 2021.

Edited by:

Charlotte R. Blease, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, United StatesReviewed by:

Theerawit Wilaiprasitporn, Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology, ThailandCopyright © 2021 Akbarialiabad, Bastani, Taghrir, Paydar, Ghahramani and Kumar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Manasi Kumar, bS5rdW1hckB1Y2wuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.