95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

STUDY PROTOCOL article

Front. Psychiatry , 25 May 2021

Sec. Psychological Therapies

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.682965

This article is part of the Research Topic Insights in Psychological Therapies: 2021 View all 7 articles

Andrea S. Hartmann1*†

Andrea S. Hartmann1*† Michaela Schmidt1†

Michaela Schmidt1† Thomas Staufenbiel2

Thomas Staufenbiel2 David D. Ebert3

David D. Ebert3 Alexandra Martin4

Alexandra Martin4 Katrin Schoenenberg4

Katrin Schoenenberg4Background: Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a relatively common mental disorder in adolescents and young adults, and is characterized by severe negative psychosocial consequences and high comorbidity as well as high mortality rates, mainly due to suicides. While patients in Germany have health insurance-financed access to evidence-based outpatient treatments, that is, cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT), waiting lists are long. Furthermore, patients with BDD report diverse treatment barriers, primarily feelings of shame and the belief that they would be better off with treatments that would alter the perceived flaw(s). Given adolescents' and young adults' high affinity to electronic media, the accessibility of evidence-based care for this severe mental disorder could be improved by providing an internet-based therapist-guided CBT intervention.

Methods: In a two-arm randomized controlled trial (N = 40), adolescents and young adults (15–21 years) with a primary diagnosis of BDD based on a semi-structured clinical expert interview will be randomly allocated to an internet-based therapist-guided CBT intervention or a supportive internet-based therapy intervention. Assessments will take place at baseline, after mid-intervention (after 6 weeks), post-intervention, and at 4-week follow-up. The primary outcome is expert-rated BDD symptom severity at the primary endpoint post-intervention. Secondary outcomes include responder and remission rates based on expert rating, self-reported BDD symptoms, and psychosocial variables associated with BDD.

Interventions: The CBT-based intervention consists of six modules each comprising one to three sessions, which focus on psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, work on self-esteem, exposure and ritual prevention, mirror retraining, and relapse prevention. A study therapist provides feedback after each session. The supportive therapy intervention consists of access to psychoeducational materials for the same 12-week period and at least one weekly supportive interaction with the study therapist.

Conclusions: This is the first study to examine the feasibility and efficacy of an internet-based therapist-guided CBT intervention in adolescents and young adults with BDD. It could be an important first step to increase accessibility of care in this age group and for this severe and debilitating mental disorder.

Clinical Trial Registration: German Register of Clinical Studies, DRKS00022055.

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is characterized by one or more perceived flaws in one's body, which are not visible or appear minor to others [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5; (1)]. Appearance-related concerns can be delusional [i.e., individuals do not understand that their perception of their own appearance differs from reality; (2)], and there is evidence that BDD is linked to more delusional concerns in adolescence than in adulthood (3). These appearance-related concerns lead to negative emotions such as shame, anxiety, and depression (4). Moreover, they are accompanied by so-called safety behaviors, which are compulsive and mental rituals performed in order to check, fix, or improve the perceived flaw(s) (1). Further typical examples of safety behaviors include rumination processes (5) and avoidance of situations in which one is confronted with one's appearance flaws or in which the perceived flaws are exposed to others [e.g., looking at oneself in the mirror, going to a party; (6)].

Various studies hint at a similar phenomenological picture of BDD in adolescents and adults [e.g., (3, 7–14)]. BDD is highly debilitating, with case studies in children and adolescents showing that BDD sufferers achieve poorer school grades (15), give up leisure time activities (12), miss a lot of school (16) or even drop out of school (15), withdraw socially (12), and might even become housebound (14). Comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception (14), and the disorder is characterized by low self-esteem and low quality of life [e.g., (17, 18)] as well as high rates of suicidality (19). Thus, BDD is a severe mental disorder, for which adolescence is a critical age period given the mean age of onset at 16 years (20) and the particularly high prevalence rate of 3.6% among 15–21-year-olds (19). Against this background, the need for adequate treatment for this age group is clear.

Two meta-analyses summarized the growing number of randomized controlled treatment trials in BDD, and concluded that cognitive-behavioral therapy and a pharmacological intervention with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) represent first-choice treatments (21, 22). Evidence in adolescents is far more limited, although case studies also support the effectiveness of CBT (15, 23–25) and SSRIs (14–16, 24, 26). Two larger studies established the feasibility of CBT for BDD in adolescents (26) and the superiority of CBT over a control condition consisting of telephone monitoring and psychoeducational materials (27).

Despite being a therapy method that is financed by health care insurers, waiting lists for CBT for adolescents in Germany are long (28). Furthermore, BDD might still be relatively unknown to practitioners and appearance concerns might be mistaken for age-appropriate concerns that do not require therapeutic attention. Additionally, many patients with BDD are very reluctant to seek psychological treatment (29), mainly due to shame, but also the idea that a treatment that changes the perceived flaw (i.e., plastic surgery, dermatology) might be more suitable for their problem. Given the highly relevant role of body image in the transitions occurring during adolescence (30) and the long-term severe consequences for future development potentially caused by BDD, an adequate treatment of BDD in adolescence is indispensable but is hindered, among other things, by the aforementioned factors.

One possibility to overcome these hindrances is an internet-based intervention. On the one hand, adolescents show a high affinity to electronic media and high acceptance rates of internet-based interventions (31). On the other hand, internet-based interventions have proven to be effective for various mental disorders in children and adolescents [for a meta-analytic overview: (32)]. The applicability of this modality for BDD treatment is further supported by a study which demonstrated the effectiveness of an internet-based therapist-guided CBT intervention in adults with BDD (33). Therefore, we developed a therapist-guided internet-based cognitive-behavioral (CBT) intervention in the style of an adult therapist-guided internet-based CBT intervention, which focused on clinical and subthreshold forms of BDD (Schoenenberg and Martin, unpublished manuscript: Online Behandlung der Körperdysmorphen Störung: Das imagin Programm [Online treatment of Body Dysmorphic Disorder: the “Imagin” program]; DRKS00015626) and was inspired by CBT manuals for the treatment of BDD (34, 35).

The main aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of an internet-based therapist-guided CBT intervention (ImaginYouth) for reducing symptoms of BDD in adolescents and young adults (in the following named adolescents) and to evaluate its superiority over a supportive online therapy condition (SOT) from pre- to post-intervention. Furthermore, we aim to assess the stability of both efficacy and superiority to follow-up, and the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention format.

We hypothesize that the ImaginYouth intervention will reduce primary expert-rated BDD symptom severity from pre- to post-intervention. Further, we expect the reduction of primary BDD symptom severity to be greater in the ImaginYouth than in the SOT intervention group from pre- to post-intervention. Secondary analyses include the testing of the above-mentioned hypotheses regarding self-reported BDD-symptom severity and associated (comorbid) symptoms. Additionally, we hypothesize that the number of remitted patients and responders will be higher at post-intervention in the ImaginYouth than in the SOT intervention group. Moreover, we expect both the changes and differences between the conditions at post-intervention to be stable over the 4-week follow-up period, and thus hypothesize a significant symptom reduction from pre-intervention to follow-up and a larger symptom reduction from pre-intervention to follow-up in the ImaginYouth compared to the SOT intervention.

A two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) will be conducted to evaluate the internet-based therapist- guided CBT intervention compared to a supportive online therapy intervention. After screening (t0), assessments will take place at baseline (t1), mid-intervention (t2), post-intervention (t3), and 4-week follow-up (t4). Figure 1 provides a detailed overview of the study design. The mid-intervention assessment will not be a focus of the main study and therefore of this protocol, but will be used to identify, for example, predictors and early responders in secondary exploratory analyses. All procedures involved in the study will be consistent with the generally accepted standards of ethical practice approved by the Osnabrück University ethics committee (Ethik-35/2018). The trial is registered in the German Register of Clinical Studies (Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien; DRKS00022055).

Inclusion criteria include age between 15 and 21 years, a primary diagnosis of BDD (comorbid diagnoses are allowed) established by the expert interview Body Dysmorphic Disorder Diagnostic Module for DSM-5 [BDDDM; (36)] after a previous sum score of ≥14 on the Body Dysmorphic Symptoms Inventory [BDDI as is in the Table; (37)] during the screening. Exclusion criteria current substance abuse, bipolar or psychotic episodes, suicidal intent and plans, current psychotherapy, cognitive limitations that would hinder work on the intervention, and/or a change in psychopharmacological medication in the last 2 months.

Recruitment will take place in mainly German-language countries (i.e., Germany, Austria, Switzerland) and will mostly be performed online through social media (e. g., Instagram, Facebook, YouTube), the study's website, and thematic websites. Furthermore, we will announce the start of the study (including in-depth information on the intervention and contact details) in a University press release, in newspapers, youth-specific magazines, student mailing lists/newsletters, student counseling centers or organizations, and to therapists affiliated with Osnabrück University.

After participants have contacted us by telephone, email or via our social media channels, they will be provided with a link to the online self-report screening (t0, in Unipark; EFS Survey, Questback GmbH, Cologne) through a self-chosen email address. If they fulfill the first inclusion criteria (age, BDDI as is in Table sum score ≥14, and no current psychotherapy), the diagnostician (a clinical psychologist in training) will contact them by email in order to make an appointment to (1) conduct the informed consent procedure and (2) complete the structured clinical interviews. The diagnostician is blind to the condition of the participant both at pre- and post-assessment. In case of crossover (i.e., a participation in ImaginYouth after having participated in SOT before) the ratings will not be blind anymore. The diagnostician will also provide the participants with detailed written information on the study procedure, our privacy policy and a note that it is possible to withdraw from the intervention at any time without facing any consequences. The informed consent procedure and the interviews will be conducted online using RedConnect (RED Medical Systems GmbH, Munich), the latter only after the informed consent form has been sent to the diagnostician by email. If the participants fulfill the remaining inclusion and exclusion criteria, they will then be randomized to one of the two intervention conditions by our external collaboration partners (AM and KS) who, from this point, will not be further involved in the study. A full randomization of the prospective 40 cases will be generated via a list randomizer (RANDOM.ORG, Randomness and Integrity Services Ltd, Dublin) by KS. Once randomization has been conducted, the second first-author (MS; study therapist in both conditions; clinical psychologist in training) will provide participants with a log-in for the intervention to which they have been allocated on the e-mental-health platform Minddistrict (Minddistrict, Berlin).

The development of the therapist-guided internet-based CBT intervention was inspired by a therapist-guided internet-based CBT intervention for adults with clinical and subthreshold BDD, “the Imagin program” (Schoenenberg and Martin, unpublished manuscript). From this program, we adopted the overall structure as well as some exercises, headers, images and videos. However, this was strongly adapted to fit the younger participants. As such, we introduced a different order of modules, a different emphasis on certain topics over others, mostly new psychoeducational reading materials, exercises and homework, a different underlying etiological model, and a different structure and composition of single sessions.

ImaginYouth consists of six modules comprising one to three sessions each. Each session can be completed in about 30–60 min and participants are advised to find a specific day on which they can take part in one session on the same day each week. If participants stick to their schedule, the intervention will last for 12 weeks. At the beginning of each session, participants are asked to report on their experiences with the last session and the homework in order to give them the opportunity to reflect on their BDD development. Furthermore, they have the chance to report on their current overall emotional state and to answer an open question on this week's particular life events. Sessions consist of psychoeducational materials on the topic being worked on (e.g., safety behaviors), including summarizing recap paragraphs and optional drop-down “Read more” sections to facilitate reading. This focus is due particularly to the diverse nature of the sample, especially in terms of age and cognitive abilities. Moreover, we included optional drop-down “Practical tips” sections for some of the exercises to provide further support if needed, as well as optional drop-down “Fun fact!” sections to enhance the overall experience of undergoing the session. Overall, attempts were made to tailor the sessions to the individual needs of the participants and to give the young participants a sense of autonomy and co-determination. The written content was enhanced by drawings that emphasize the information given as well as video and audio clips. Furthermore, participants are asked to complete mandatory exercises to apply the material to their own behavior and/or perception. The content and the exercises are accompanied by three teenage case descriptions (two girls, one boy) that are introduced in the first session. These serve as relatable examples by sharing their experiences with and everyday-life application of the current topic of the session and/or sharing their answers in the exercises to give participants a better idea of what they are being asked to do. Another connecting element of the sessions is the BDD model that is introduced in the second session. This model links to the current topic at the beginning of each session to explain the rationale for the proposed exercises, and aims to increase participants' motivation. At the end of each session, participants are asked to complete a short survey (see section Assessment and Data Management). Between sessions, participants work on homework that aims to facilitate transfer to the real-world setting (e.g., diaries, exposure exercises); this is often enhanced by “cheat sheets” summarizing the crucial content of the previous session. After each session, participants receive written feedback from the study therapist on the exercises and homework through the program's chat function. At the end of each module, participants can download a handout summarizing the crucial aspects of the module in order to create their personal BDD “toolbox.” After the completion of each session, further content is automatically released. New modules need to be released by the study therapist. While the sessions and the integrated chat can only be accessed via a web browser, the homework is also available on the complementary smartphone app. Detailed information on the number of sessions per module and content are illustrated in Table 1.

A supportive therapy condition was chosen as the control condition, as this has proven to be feasible in BDD in adults (33) and in children and adolescents with depression or anxiety symptoms (38, 39). In the SOT condition, patients can read psychoeducational material on BDD for 12 weeks (symptoms, prevalence, development, maintenance, therapy options, case examples) that is identical to the psychoeducational reading material from the first module of the ImaginYouth condition, but without exercises to facilitate transfer to the patient's individual case or the identification of intervention targets. Through the program's messaging function, the control patients are contacted weekly (repeated in case of non-responding) by the study therapist. In this communication, the therapist asks about their current well-being as well as their experiences, thoughts, and emotions regarding BDD symptoms and how these influence participants' lives if participants do not bring up their own questions or concerns.

Given the high suicidality in BDD (19), we aim to provide a thorough safety management in our study. First, potential participants with concrete suicidal intentions and plans identified during screening and/or diagnostic sessions will be excluded from participation and will be informed about potential places to seek treatment in their area of residence. During the intervention, we will have a weekly monitoring of suicidal ideation in place, which the study therapist has to consult prior to interaction with the patient. If suicidal ideation develops, a stepped-care plan will be set in motion, including anti-suicide contracts, a telephone call with the study therapist in which a stepped emergency plan is developed, a telephone call with the supervisor (AH; a clinical psychologist with expertise in treatment of BDD), and involvement of treatment providers in the patient's area of residence. In order to track the general development of all patients, a fortnightly supervision session will be held. The supervisor will be accessible for the study therapist during the whole project. For post-hoc analyses, we will also assess adverse events during and after the intervention (see measures) to assess its moderation of treatment effects.

Quality management (i.e., adherence to condition and engagement) will include the aforementioned fortnightly supervision session, measurement of the time used to communicate with each patient as well as number of messages. Messages between patients and study therapist are in written format only, are recorded, and can be subject to content analysis of adherence to condition during data analysis. Furthermore, diagnostic sessions will be recorded and interrater reliability will be calculated in 20% of randomly chosen cases. The diagnostician will be blind to the randomization of the participants and will be replaced if deblinded.

Detailed self-reports will take place at screening (t0), baseline (t1) prior to randomization, mid-intervention (t2), post-intervention (t3), and 4-week follow-up (t4; see Figure 1 for a detailed overview). On a more regular basis, we will gather brief self-reports on suicidal intent and negative emotions (after each session) as well as on BDD and depressive symptoms (after each module). Self-reported data (t0 through t4) will be collected using the secure online-based assessment system Unipark (EFS Survey, Questback GmbH, Cologne). Expert interviews will be conducted over the internet at t1 and t3 via the secure online video conferencing platform RedConnect (RED Medical Systems GmbH, Munich).

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder [BDD-YBOCS; (40); German version: (41)]. The main primary outcome assessing severity of BDD symptoms will be the semi-structured expert clinical interview BDD-YBOCS (40). This will also be used to assess responder and remission status (42). The BDD-YBOCS is the gold standard instrument and assesses both cognitive (e.g., time occupied by thoughts about body defect) and behavioral symptoms (e.g., degree of control over compulsive behavior) of BDD and delusionality using a total of 12 items. The item regarding delusionality will be rated again within the participants' answers on the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale [BABS; (43)]. Items on the BDD-YBOCS are rated on a 5-point Likert Scale from 0 to 4, with the scale content depending on the respective item (e.g., 0 = none to 4 = extreme [spends more than 8 h/day on these activities]). The scale has shown good internal consistency (0.80) and interrater reliability [0.99; (40)].

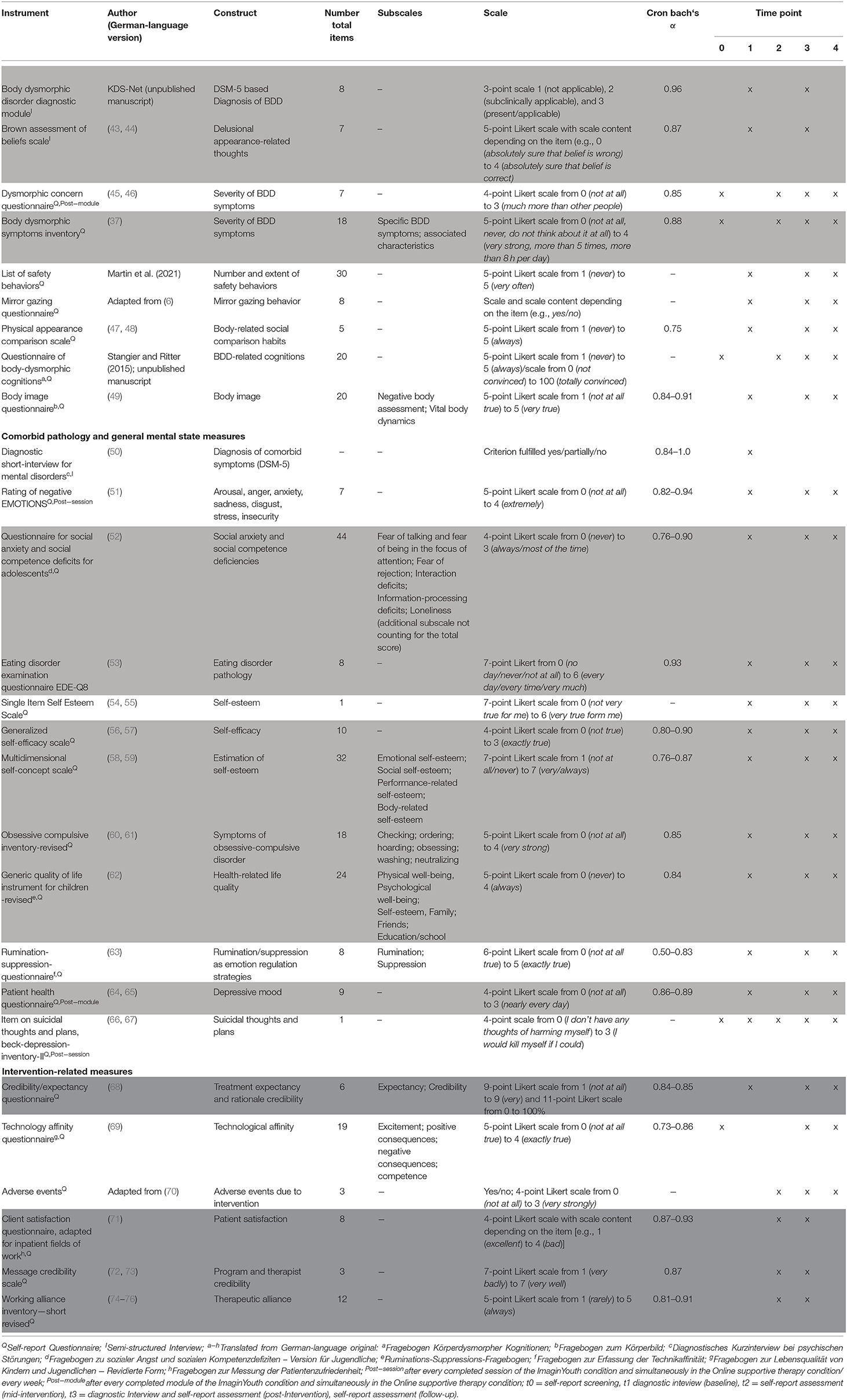

Detailed information on number of scales, items, content scaling, and psychometric properties of all secondary measures (both for further BDD-symptoms and comorbid psychopathology) included in this protocol and primary analyses are highlighted in light gray in Table 2. Table 2 also presents all other variables assessed in the study but not in the focus of the main analyses of the study. Some measures will be administered after each session and/or each module, which is indicated by superscripted post-module or post-session mention.

Table 2. Description of instruments and psychometric characteristics as well as points of measurement.

Feasibility and acceptability will be measured using the instruments highlighted in dark gray in Table 2.

All statistical analyses will be conducted using SPSS Statistics (IBM; Armonk, New York, USA) and R (77). Data will be mainly analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis including all randomized participants irrespective of their completion of the intervention. Additionally, study completer analyses including only participants who completed the post-intervention questionnaire battery and interviews will be conducted. Missing data will be imputed. Dropouts and completers will be compared with respect to study variables.

The main analysis focusing on efficacy of ImaginYouth will be analyzed using a repeated measures analysis of variance (rmANOVA) comparing pre- to post- intervention scores of the primary outcome. For the main analysis focusing on superiority of ImaginYouth over the SOT intervention, we will conduct a rmANOVA in the primary outcome between the two intervention conditions and changes from pre- to post-intervention. Post-hoc t-tests will be used to examine main effects or interactions in more detail. Cohen's d will be reported as a measure of effect size.

Secondary analyses include the examination of categorical hypotheses [e.g., for the examination of differences between ImaginYouth and SOT in responder (defined as an empirically derived cut-off point of ≥30% reduction from baseline on the BDD-YBOCS), and remission rates (operationalized as a BDD-YBOCS score ≤16 (42))] at post-intervention using Fisher's exact test. Hypotheses on efficacy and superiority regarding self-reported BDD-symptoms severity and associated (comorbid) symptoms will also be tested rmANOVAs (see above). Stability over the follow-up period and differences therein between ImaginYouth and SOT will be tested using a rmANOVA comparing pre-intervention to follow-up scores of self-reported BDD symptom severity. Finally, to examine the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, the respective measures will be inspected descriptively.

Our a priori power analysis using G*Power (78) focused on the main hypothesis of a greater reduction of BDD symptoms in the main outcome measure from pre- to post-intervention in the ImaginYouth than in the SOT group. Thus, we calculated the number of participants necessary to test the interaction effect in a 2 (intervention type) × 2 (repeated measures assessment point) analysis of variance.

The power analysis was based on α= 0.05 and 1-β= 0.95, and an effect size of f = 0.36 [yielded by a meta-analysis on effects in internet-based intervention studies in youth by (32)]. The resulting total sample size is n = 28. Taking into account expected dropouts [about 30% in internet-based studies; (79)], we aim to recruit 20 patients per study arm type.

The aim of this two-arm randomized controlled trial is to evaluate the efficacy of an internet-based therapist-guided CBT intervention (ImaginYouth) and its superiority over SOT for BDD in adolescents. Furthermore, we aim to assess the stability in terms of both efficacy and superiority over a period of 4 weeks post-intervention, as well as the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention format. It is hypothesized that ImaginYouth will reduce primary and secondary BDD symptoms from pre- to mid-, post-, and follow-up assessments. We further expect the reduction of primary and secondary BDD symptoms to be larger in the ImaginYouth group compared to the SOT group from pre- to mid-, post-, and follow-up assessment. Additionally, we hypothesize that the number of remitted patients and repsonders at post-assessment will be higher in the ImaginYouth than in the SOT intervention group.

ImaginYouth provides participants with a CBT-based intervention which makes use of techniques that are currently the first-line treatment recommended in adults (80, 81) and have shown first efficacy in youth as well (82). The ImaginYouth intervention removes some of the treatment barriers which young individuals with BDD might face. Particularly, it might not involve as many feelings of shame. Even though participation is not completely anonymous, contact with study staff (diagnostician and study therapist) do not need to involve personal face-to-face contact. We nevertheless decided in favor of a therapist-guided intervention as guidance has also been shown to increase adherence rates in internet-based interventions (83). ImaginYouth consists of interventions on cognitive, emotional, and behavioral levels, as do treatment manuals for BDD (34, 35). Thus, effects of the intervention should be perceived and measured on all levels (see secondary measures). Moreover, as previous online CBT interventions in BDD have shown (33), effects can also be measured with regard to comorbid psychopathology (e.g., a decrease in depressive symptoms as a consequence of reduced social withdrawal or cognitive restructuring of negative thoughts).

The current design has several advantages and disadvantages. We decided in favor of an older adolescent sample mainly in order to test the intervention in individuals who are able to participate in the trial independently of their caregivers and of their own volition, in order again to limit feelings of shame when having to ask caregivers for permission. Nevertheless, in the future, the intervention could be adapted for younger adolescents and children and also expanded to be suitable for caregivers. Furthermore, we chose a randomized controlled design with an active instead of a waitlist control group, which has the advantage that we will be able to closely monitor and attend to participants in the control group. This is important as, like in other internet- and mobile-based interventions, safety management is difficult to perform, and we have tried to combat this by preparing a multilevel anti-suicidality approach. Another advantage is that participants in SOT will already receive some help that might lead to improvement, allowing unspecific working mechanisms to be controlled for. While we cannot assess long-term stability with the current design with a follow-up period of 4 weeks, the aim of the study is to assess, for the first time, the short-term efficacy in youth with BDD and to allow participants in the SOT condition to cross over to the ImaginYouth condition swiftly. Furthermore, we decided in favor of non-standardized messages after each session of ImaginYouth (and during the SOT) by the therapist, with the therapist instead adapting her comments to the patients. While this might limit generalizability, it might on the other hand decrease dropouts. And lastly, video but not audio recording during the diagnostic sessions will be non-mandatory, as this might hinder potential patients from participating. Thus, we cannot use this option to completely rule out any objective facial flaws in appearance (if other flaws are primary video recording would not be helpful anyway).

To conclude, this internet-based therapist-guided CBT intervention is a treatment that aims to reduce symptoms in adolescents with BDD. Given the scarcity of intervention research in adolescents with BDD, this study will start to close this research gap, illustrating the efficacy of CBT and superiority over supportive therapy in adolescents with BDD, as well as providing information on the acceptability and feasibility of the online format. This format might be especially ideal when targeting this population, as it can be used independently of place and time, by affected individuals who are highly tech-savvy. Furthermore, it might make treatment for BDD more accessible despite high experiences of shame in youth with BDD, and in view of the current limited availability of high-quality treatment as well as long waiting lists.

AH, TS, DE, AM, and KS designed the study. AH and MS drafted the manuscript, supervised by KS. TS, DE, and AM contributed to the further writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was funded by a grant to AH by the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (2018_A160). We further acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and Open Access Publishing Fund of Osnabrück University for the publication of the article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

2. Phillips KA. Psychosis in body dysmorphic disorder. J Psychiatr Res. (2004) 38:63–72. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(03)00098-0

3. Phillips KA, Didie ER, Menard W, Pagano ME, Fay C, Weisberg RB. Clinical features of body dysmorphic disorder in adolescents and adults. Psychiatry Res. (2006) 141:305–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.09.014

4. Kollei I, Martin A. Body-related cognitions, affect and post-event processing in body dysmorphic disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2014) 45:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.09.005

5. Veale D. Advances in a cognitive behavioural model of body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image. (2004) 1:113–25. doi: 10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00009

6. Veale D, Riley S. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the ugliest of them all? The psychopathology of mirror gazing in body dysmorphic disorder. Behav Res Ther. (2001) 39:1381–93. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00102-9

8. Cotterill J. Dermatological non-disease: a common and potentially fatal disturbance of cutaneous body image. Br J Dermatol. (1981) 104:611–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb00746.x

9. Braddock LE. Dysmorphophobia in adolescence: a case report. Br J Psychiatry. (1982) 140:199–201. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.2.199

10. Sondheimer A. Clomipramine treatment of delusional disorder-somatic type. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1988) 27:188–92. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198803000-00010

11. Phillips KA, Susan L, McElroy M, Keck Jr PE. A comparison of delusional and nondelusional body dysmorphic disorder in 100 cases. Psychopharmacol. Bull. (1994) 30:179–86.

12. El-khatib HE, Dickey T. Sertraline for body dysmorphic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1995) 34:1404–5. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199511000-00004

13. Heimann SW. SSRI for body dysmorphic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1997) 36:686. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00004

14. Albertini RS, Phillips KA. Thirty-three cases of body dysmorphic disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1999) 38:453–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199904000-00019

15. Phillips KA, Atala KD, Pope HG. Diagnostic instruments for body dysmorphic disorder. In: American Psychiatric Association 148th Annual Meeting. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association. (1995).

16. Albertini RS, Phillips KA, Guevremont D. Body dysmorphic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1996) 35:1425. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00010

17. IsHak WW, Bolton MA, Bensoussan J-C, Dous GV, Nguyen TT, Powell-Hicks AL, et al. Quality of life in body dysmorphic disorder. CNS Sprectr. (2012) 17:167–75. doi: 10.1017/S1092852912000624

18. Kuck N, Cafitz L, Bürkner P, Nosthoff-Horstmann L, Wilhelm S, Buhlmann U. Body dysmorphic disorder and self-esteem: a meta-analysis. PsyArXiv. (2020). doi: 10.31234/osf.io/5g32t. [Epub ahead of print].

19. Möllmann A, Dietel FA, Hunger A, Buhlmann U. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder and associated features in German adolescents: a self-report survey. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 254:263–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.063

20. Bjornsson AS, Didie ER, Grant JE, Menard W, Stalker E, Phillips KA. Age at onset and clinical correlates in body dysmorphic disorder. Compr Psychiatry. (2013) 54:893–903. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.03.019

21. Williams J, Hadjistavropoulos T, Sharpe D. A meta-analysis of psychological and pharmacological treatments for body dysmorphic disorder. Behav Res Ther. (2006) 44:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.006

22. Harrison A, de la Cruz LF, Enander J, Radua J, Mataix-Cols D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. (2016) 48:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.007

23. Sobanski E, Schmidt M. ‘Everybody looks at my pubic bone’—a case report of an adolescent patient with body dysmorphic disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2000) 101:80–2. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101001080.x

24. Horowitz K, Gorfinkle K, Lewis O, Phillips KA. Body dysmorphic disorder in an adolescent girl. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2002) 41:1503. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200212000-00023

25. Aldea MA, Storch EA, Geffken GR, Murphy TK. Intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder. Clin Case Stud. (2009) 8:113–21. doi: 10.1177/1534650109332485

26. Greenberg JL, Mothi SS, Wilhelm S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent body dysmorphic disorder: A pilot study. Behav Ther. (2016) 47:213–24. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.10.009

27. Mataix-Cols D, de la Cruz LF, Isomura K, Anson M, Turner C, Monzani B, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2015) 54:895–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.08.011

28. BundesPsychotherapeutenKammer. (2018). Ein Jahr nach der Reform der Psychotherapie-Richtlinie: Wartezeiten 2018. Availabloe online at: https://www.bptk.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/20180411_bptk_studie_wartezeiten_2018.pdf (accessed December 31, 2020).

29. Schulte J, Schulz C, Wilhelm S, Buhlmann U. Treatment utilization and treatment barriers in individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02489-0

31. Sweeney GM, Donovan CL, March S, Forbes Y. Logging into therapy: Adolescent perceptions of online therapies for mental health problems. Internet Interv. (2019) 15:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.12.001

32. Ebert DD, Zarski A.-C, Christensen H, Stikkelbroek Y, Cuijpers P, et al. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0119895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119895

33. Enander J, Andersson E, Mataix-Cols D, Lichtenstein L, Alström K, Andersson G, et al. Therapist guided internet based cognitive behavioural therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: Single blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ. (2016) 352:i241. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i241

34. Veale D, Neziroglu FA. Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Treatment Manual. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd (2010).

35. Wilhelm S, Phillips K, Steketee G. A Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Manual for Body Dysmorphic Disorder. New York, NY: Guilford (2013).

36. Phillips KA. Body Dysmorphic Disorder Diagnostic Module. Belmont, Massachusetts: McLean Hospital (1994).

37. Buhlmann U, Wilhelm S, Glaesmer H, Brähler E, Rief W. Fragebogen körperdysmorpher Symptome (FKS): Ein Screening-Instrument. Verhaltenstherapie. (2009) 19:237–42. doi: 10.1159/000246278

38. Khanna MS, Kendall PC. Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2010) 78:737. doi: 10.1037/a0019739

39. Stasiak K, Hatcher S, Frampton C, Merry SN. A pilot double blind randomized placebo controlled trial of a prototype computer-based cognitive behavioural therapy program for adolescents with symptoms of depression. Behav Cogn Psychother. (2014) 42:385. doi: 10.1017/S1352465812001087

40. Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, Aronowitz BR, DeCaria C, Goodman WK. A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. (1997) 33:17–22.

41. Stangier U, Hungerbühler R, Hungerbühler R, Meyer A, Wolter M. Diagnostische Erfassung der Körperdysmorphen Störung: Eine Pilotstudie. Nervenarzt. (2000) 71:876–84. doi: 10.1007/s001150050678

42. Fernández de la Cruz L, Enander J, Rück C, Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Steketee G, et al. Empirically defining treatment response and remission in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychol Med. (2021) 51:83–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003003

43. Buhlmann U. The German version of the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS): Development and evaluation of its psychometric properties. Compr Psychiatry. (2014) 55:1968–71. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.011

44. Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, Beer DA, Atala KD, Rasmussen SA. The brown assessment of beliefs scale: reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry. (1998) 155:102–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.102

45. Oosthuizen P, Lambert T, Castle DJ. Dysmorphic concern: Prevalence and associations with clinical variables. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (1998) 32:129–32. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062719

46. Schieber K, Kollei I, de Zwaan M, Martin A. The dysmorphic concern questionnaire in the German general population: psychometric properties and normative data. Aesthetic Plast Surg. (2018) 42:1412–20. doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1183-1

47. Thompson JK, Fabian LJ, Moulton DO, Dunn ME, Altabe MN. Development and validation of the physical appearance related teasing scale. J Pers Ass. (1991) 56:513–21. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5603_12

48. Mölbert CS, Hautzinger M, Karnath HO, Zipfel S, Giel K. Validation of the physical appearance comparison scale (PACS) in a German sample: psychometric properties and association with eating behavior, body image and self-esteem. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. (2017) 67:91–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-123842

49. Clement U, Löwe B. Die Validierung des FKB-20 als Instrument zur Erfassung von Körperbildstörungen bei psychosomatischen Patienten. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. (1996) 46:254–9.

50. Margraf J, Cwik JC. Mini-DIPS open access: Diagnostic short-interview for mental disorders. Bochum: Forschungs- und Behandlungszentrum für psychische Gesundheit, Ruhr-Universität (2017).

51. Vocks S, Legenbauer T, Wachter A, Wucherer M, Kosfelder J. What happens in the course of body exposure? Emotional, cognitive, and physiological reactions to mirror confrontation in eating disorders. J Psychosom Res. (2007) 62:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.08.007

52. Castelao CF, Kolbeck S, Ruhl U. SASKO-J: Fragebogen zu sozialer Angst und sozialen Kompetenzdefiziten Version für Jugendliche: Manual. Göttingen: Hogrefe (2017).

53. Kliem S, Mößle T, Zenger M, Strauss BM, Brähler E, Hilbert A. The Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire 8: A brief measure of eating disorder pathology (EDE-Q8). Int J Eat Disord. (2016) 49:613–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.22487

54. Robins RW, Hendin HM, Trzesniewski KH. Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (2001) 27:151–61. doi: 10.1177/0146167201272002

55. Brailovskaia J, Margraf J. How to measure self-esteem with one item? Validation of the German single-item self-esteem scale (G-SISE). Curr Psychol. (2020) 39:2192–202. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9911-x

56. Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. Measures in health psychology: A user's portfolio. Causal Control Beliefs. (1995) 1:35–7.

57. Jerusalem M, Schwarzer R. Skala zur allgemeinen Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin (1999).

58. Fleming JS, Courtney BE. The dimensionality of self-esteem: II. Hierarchical facet model for revised measurement scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1984) 46:404–21. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.2.404

60. Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, et al. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess. (2002) 14:485. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.4.485

61. Gönner S, Ecker W, Leonhart R. Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory Revised (OCI-R). Deutsche Adaptation. Manual. Frankfurt/Main: Pearson Assessment and Information (2009).

62. Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. Assessing health-related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content analytical results. Qual Life Res. (1998) 7:399–407. doi: 10.1023/A:1008853819715

63. Pjanic I, Bachmann MS, Znoj H, Messerli-Bürgy N. Entwicklung eines Screening-Instruments zu Rumination und Suppression RS-8. PPmP Psychother. Psychosom. Medizinische Psychol. (2013) 63:456–62. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333302

64. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD — the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. (1999) 282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

65. Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Gräfe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord. (2004) 81:61–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(03)00198-8

66. Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Ass. (1996) 67:588–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13

67. Hautzinger M, Keller F, Kühner C. BDI-II Beck Depressions-Inventar. Frankfurt am Main: Harcourt Test Services (2010).

68. Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2000) 31:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4

69. Karrer K, Glaser C, Clemens C, Bruder C. Technikaffinität erfassen–der Fragebogen TA-EG. Der Mensch im Mittelpunkt technischer Systeme. (2009) 8:196–201.

70. Rozental A, Andersson G, Boettcher J, Ebert DD, Cuijpers P, Knaevelsrud C, et al. Consensus statement on defining and measuring negative effects of internet interventions. Internet Interv. (2014) 1:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.02.001

71. Schmidt J, Lamprecht F, Wittmann WW. Zufriedenheit mit der stationären Versorgung. Entwicklung eines Fragebogens und erste Validitätsuntersuchungen. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. (1989) 39:248–55.

72. Appelman A, Sundar SS. Measuring message credibility. J Mass Commun. Q. (2015) 93:59–79. doi: 10.1177/1077699015606057

73. Thielsch MT, Hirschfeld G. Quick assessment of web content perceptions. Int J Hum-Comput Int. (2021) 37:68–80. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2020.1805877

74. Horvath AO, Greenberg L. The development of the working alliance inventory. In: Greenberg L. Pinsoff W, editors. The Psychotherapeutic Process: A Research Handbook. New York, NY: Guilford (1986). p. 529–56.

75. Wilmers F, Munder T, Leonhart R, Herzog T, Plassmann R, Barth J, et al. Die deutschsprachige Version des Working Alliance Inventory-short revised (WAI-SR)-Ein schulenübergreifendes, ökonomisches und empirisch validiertes Instrument zur Erfassung der therapeutischen Allianz. Klinische Diagnostik und Evaluation. (2008) 1:343–58.

76. Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of counseling psychology. (1989) 36:223. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223

77. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2017). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/

78. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. (2007) 39:175–91. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

79. Melville KM, Casey LM, Kavanagh DJ. Dropout from Internet-based treatment for psychological disorders. Br J Clin Psychol. (2010) 49:455–71. doi: 10.1348/014466509X472138

80. Veale D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiatr Ann. (2010) 40:333–40. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20100701-06

81. Mancusi L, Ojserkis R, McKay D. Treatment of Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons Ltd (2017).

82. Krebs G, Fernandez de la Cruz L, Monzani B, Bowyer L, Anson M, Cadman J, et al. Long-term outcomes of cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent body dysmorphic disorder. Behav Ther. (2017) 48:462–73. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.01.001

Keywords: adolescents, cognitive behavioral therapy, internet-based intervention, appearance concerns, body dysmorphic disorder, young adults, e-mental health

Citation: Hartmann AS, Schmidt M, Staufenbiel T, Ebert DD, Martin A and Schoenenberg K (2021) ImaginYouth—A Therapist-Guided Internet-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Program for Adolescents and Young Adults With Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Study Protocol for a Two-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychiatry 12:682965. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.682965

Received: 19 March 2021; Accepted: 19 April 2021;

Published: 25 May 2021.

Edited by:

Derek Richards, Trinity College Dublin, IrelandReviewed by:

Hilary Weingarden, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Hartmann, Schmidt, Staufenbiel, Ebert, Martin and Schoenenberg. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea S. Hartmann, YW5kcmVhLmhhcnRtYW5uQHVvcy5kZQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.