- 1Beijing Key Laboratory of Mental Disorders, The National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders, The Advanced Innovation Center for Human Brain Protection, Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 2Unit of Psychiatry, Department of Public Health and Medicinal Administration, Faculty of Health Sciences, Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences, University of Macau, Macao, China

- 3Institute of Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Macau, Macao, China

- 4School of Nursing, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China

- 5Department of Psychiatry, The Melbourne Clinic, St Vincent's Hospital, University of Melbourne, Richmond, VIC, Australia

Aims: Carers of psychiatric patients often suffered from mental and physical burden during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic due to the lack of mental health services. This study investigated the pattern of fatigue and its association with quality of life (QOL) among the carers of patients attending psychiatric emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, carers of patients attending psychiatric emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic were consecutively included. Fatigue, insomnia symptoms, depressive symptoms, and QOL were assessed with standardized instruments.

Results: A total of 496 participants were included. The prevalence of fatigue was 44.0% (95% CI = 39.6–48.4%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that fatigue was positively associated with higher education level (OR = 1.92, P < 0.01) and more severe depressive (OR = 1.18, P < 0.01) and insomnia symptoms (OR = 1.11, P < 0.01). ANCOVA analysis revealed that the QOL was significantly lower in carers with fatigue compared with those without (P = 0.03).

Conclusions: Fatigue was common among carers of patients attending psychiatric emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the adverse impact of fatigue on QOL and other health outcomes, routine screening and appropriate intervention for fatigue are warranted for this subpopulation.

Introduction

As of the end of April 2021, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which was declared as a pandemic (1), has been reported in more than 200 countries/territories and caused more than 143 million confirmed cases and over 3 million deaths worldwide (2). Patients with psychiatric disorders have an increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality (3). In China, due to the lack of community mental health services, maintenance psychiatric treatments are mostly provided by outpatient departments of psychiatric hospitals, which are mostly located in urban areas (4, 5). During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the lockdown restrictions and quarantine measures have prevented psychiatric patients from visiting psychiatric outpatient services, hindering their maintenance therapy (6). Moreover, visits to psychiatric outpatient departments may increase patients' exposure to nosocomial infections during the pandemic. For example, over 300 patients with psychiatric disorders were infected with the COVID-19 at the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in China (7). Hence, to reduce the risk of transmission, outpatient services in many psychiatric hospitals were restricted or suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, these factors have reduced the access to mental health services and maintenance treatment for psychiatric patients, which has led to more frequent illness relapses and presentations to psychiatric emergency services.

In China, the carers of psychiatric patients (i.e., spouse, parents, adult children, and close relatives and friends) are usually responsible for supervising their medication adherence at home. Additionally, the stigmatization, social discrimination, and economic burden of caring for their family member with psychiatric disorder, often lead to the carers' mental and physical distress (8–12). Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the carer' burden has increased due to several patient factors such as impaired cognition, unhealthy lifestyle, poor self-care, and suboptimal health status, all of which could increase the risk of infection with COVID-19 in psychiatric patients compared with those without psychiatric disorders (13, 14). Therefore, their carers had to take more precautions to remind psychiatric patients about COVID-19-related information and supervise them to comply with the preventive measures. All the abovementioned challenges are likely to exacerbate carers' mental and physical distress.

Fatigue, a major stress-related symptom, is frequently experienced by carers of psychiatric patients (15). Fatigue is a multidimensional symptom, which involves subjective (e.g., feelings of tiredness, lack of energy, and decreased motivation), behavioral (e.g., decline in performance, such as inaccuracy and/or reaction time during a cognitive task), and physiological (e.g., alterations in brain activity) components (16). It is also associated with a range of negative outcomes, including poor work performance, negative emotions (17), and even increased risk of sudden death (18).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, fatigue was examined among healthcare professionals (19–22) and the general population (23). To date, no studies on fatigue in carers of psychiatric patients during the COVID-19 pandemic have been published. In addition, the association of fatigue and quality of life (QOL) in carers of psychiatric patients has not been studied. Quality of life, as a comprehensive health outcome (24, 25), reflects individuals' perception toward their multidimensional general well-being, including physical and mental health, social ability and relationships, personal expectations, and so forth (26). Hence, this study examined the patterns of fatigue and its association with QOL among the carers of patients attending psychiatric emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from April 30 to July 4, 2020 in the Emergency Department of Beijing Anding Hospital, which provided the only psychiatric emergency services for psychiatric patients in the Beijing municipality and neighboring provinces. The carers of patients who attended the psychiatric emergency service during the study period were consecutively invited to participate in the survey. The inclusion criteria were: (1) carers of patients with psychiatric disorders according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (27), (2) aged 18 years and above, and (3) being able to understand the content of the assessment and provide written informed consent before the survey. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Anding Hospital.

Due to the risk of contagion, conventional face-to-face interviews could not be conducted. Following other studies (28–30), data collection was carried out using the WeChat-based survey program, “Questionnaire Star,” which has been commonly used in epidemiological surveys before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. WeChat is a social communication application for smartphones, with over 1 billion users in China including all the carers who were invited to participate in this study.

Evaluation and Assessment Instruments

The assessments were completed in a consultation room. The basic sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, such as age, gender, education level, employment, average personal monthly income, major medical conditions, and preexisting psychiatric disorders, were recorded. The COVID-19 outbreak-related questions with “yes/no” options, including “concerns about the COVID-19 outbreak?” and “frequent use of mass media for COVID-19 related information,” were asked.

Severity of fatigue was evaluated with the “0–10” numeric rating scale (NRS) (31), with “0” indicating “no fatigue at all” and “10” indicating “unbearable fatigue.” A score of 4 and more indicated “having fatigue” (32, 33). Severity of insomnia symptoms (insomnia hereafter) was assessed using the Chinese version of Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (34, 35), which was validated in Chinese populations (35). The ISI consisted of seven items with the total score ranging from 0 to 28. A higher total score indicated more severe insomnia. The severity of depressive symptoms (depression hereafter) was assessed using the Chinese version of the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (36, 37), which has been widely used in previous Chinese research (38). The total score of PHQ-9 ranged from 0 to 27 with a higher total score representing more severe depression. The overall QOL was evaluated with the total score of the first two items of the World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief version (WHOQOL-BREF) (39–41), with a higher score indicating higher QOL.

Data Analysis

All the data analyses were performed with the Statistic Package for Social Science (SPSS), Version 24.0. The P-P Plot was used to examine the normality of continuous variables. Univariate analyses were conducted to compare the sociodemographic and clinical data between carers with and without fatigue using two independent-sample t-tests, Mann–Whitney U-tests, and χ2 tests as appropriate. The independent associates of fatigue were tested using the binary logistic regression analysis with the “enter” method (i.e., all independent variables were included in the regression model at the same time regardless of whether the independent variables were significant or non-significant). In the logistic regression analysis, the sociodemographic and clinical variables with P < 0.1 in univariate analyses were entered as independent variables, while fatigue was the dependent variable. In addition, the independent association between fatigue and QOL was tested using the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with all variables with significant group differences in univariate analyses as covariates. The significance level was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

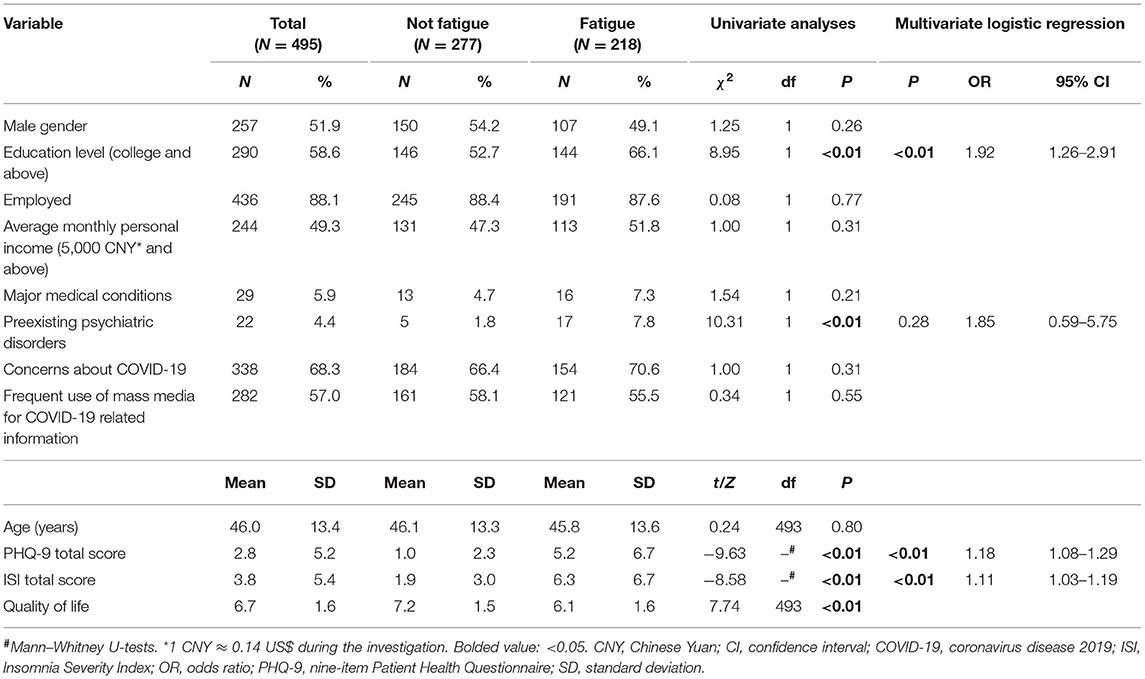

Altogether, 505 carers of patients attending psychiatric emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic were invited, of whom, 496 fulfilled the eligibility criteria and completed the assessment, giving a response rate of 98.2%. Their basic sociodemographic and clinical data are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the whole sample was 46.0 [standard deviation (SD) = 13.4] years, and 51.9% (n = 257) were males. The prevalence of fatigue was 44.0% [95% confidence interval (CI) = 39.6–48.4%), with a mean NRS score of 3.37 (SD = 2.70).

Table 1. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants and their association with fatigue.

Univariate analyses revealed that carers with fatigue were more likely to have higher education level (P < 0.01), preexisting psychiatric disorders (P < 0.01), and more severe depression (P < 0.01) and insomnia (P < 0.01). The binary logistic regression analysis found that the fatigue was positively associated with higher education level [odds ratio (OR) = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.26–2.91, P < 0.01] and more severe depression (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.08–1.29, P < 0.01) and insomnia (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.03–1.19, P < 0.01). The ANCOVA analysis revealed that carers with fatigue had significantly lower QOL than those without [F (1, 496) = 4.59, P = 0.03].

Discussion

This was the first study that examined the pattern of fatigue among carers of patients attending psychiatric emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that around half of the participants (44.0%) reported fatigue. The corresponding figure was 73.7% in Chinese frontline staff (including doctors, nurses, polices, volunteers, community workers, and journalists) during the COVID-19 pandemic (22). However, direct comparisons between studies should be made with caution due to different measurements of fatigue and sampling method.

A variety of reasons could contribute to the common occurrence of fatigue among carers of patients attending psychiatric emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, carer burden is increased during the COVID-19 pandemic as carers need to supervise patients to strictly comply with preventive and self-protection measures against the COVID-19. Second, lockdown restriction and quarantine measures as well as suspended/limited outpatient services in many hospitals could hinder or reduce access to psychiatric services, which could lead to illness relapse and increased carers' burnout and distress. Furthermore, quarantine measures could also limit carers' access to social support, such as friends and relatives who have previously helped with patient care. Third, the COVID-19 pandemic could have decreased employment opportunities and increased economic burden to the general population including the carers (42).

Fatigue was positively associated with depression in this study, which is consistent with studies in family caregivers in intensive care units (43), carers of patients with Parkinson's disease (44), and palliative care patients (45). The association between fatigue and depression is bidirectional. On one hand, fatigue could lead to negative emotions and increase the risk of depression (17, 46, 47). A longitudinal study over 13 years found that individuals with unexplained fatigue had greatly increased incidence of new episode of major depression compared with those without [risk ratio (RR) = 28.4, 95% CI = 11.7–68.0] (48). On the other hand, fatigue could also be caused by depression. It was reported that depressed patients often experience fatigue as a symptom, being one of the diagnostic criteria for major depression, which is reported in up to 87.2% of patients with major depression (49).

Previous studies have found that fatigue is one of the major consequences of insomnia (50, 51), which was confirmed in this study. With insufficient sleep, individuals may experience impaired executive function, which is associated with fatigue (52). Moreover, depression may mediate the correlation between fatigue and insomnia, as both fatigue and insomnia are key features of depression (53).

Among carers of patients with psychiatric disorders (54, 55) or physical illnesses (e.g., multiple sclerosis and cancer) (56–58), those with higher education level had more access to relevant information and had better coping patterns when caring for patients. Thus, they may have better psychological resilience and are less likely to experience health problems including fatigue. On the contrary, in this study, carers with higher education level reported more severe fatigue. We speculate that during the COVID-19 pandemic, carers with higher education level could have had more access to negative information on COVID-19, e.g., COVID-19 was repeatedly described as a “killer virus” in social media that perpetuated the sense of danger and uncertainty among the public, which may result in mental distress and fatigue.

As expected, carers with fatigue reported lower QOL than those without. Similar association was also reported among frontline staff during the COVID-19 pandemic (22). QOL is determined by the interaction between risk factors (e.g., mental and physical distress) and protective factors (e.g., good economic status and social support) based on the distress/protection QOL model (59). Fatigue is strongly associated with negative emotions [e.g., depression and anxiety (17, 46)], poor work performance, and poor physical health (18, 60, 61), all of which would lower QOL.

The strengths of this study included the relatively large sample size and use of standardized instruments. However, several methodological limitations need to be addressed. First, the causal relationship between fatigue and other variables could not be examined due to the cross-sectional design. Second, certain factors associated with fatigue and psychological burden in the carers [e.g., anxiety and somatization symptoms (22), severity and presence of physical diseases and relevant treatments, and illness duration and severity of psychiatric symptoms of the patients] were not assessed due to logistical reasons. Third, carers of patients were recruited from one psychiatric emergency service in Beijing, which limits the generalization of the findings to other areas of China.

In conclusion, fatigue is common among carers of patients attending psychiatric emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the adverse impact of fatigue on QOL and other health outcomes, routine screening and appropriate intervention for fatigue [e.g., occupational therapy (62), kinesiotherapy (63), interpersonal psychotherapy (64), and self-administered acupressure (65)] are warranted for this subpopulation.

Data Availability Statement

The ethics committee of Beijing Anding Hospital that approved the study prohibits the authors from making the research dataset of clinical studies publicly available. Readers and all interested researchers may contact Dr. YT Xiang (Email address: eHl1dGx5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==) for details. Dr. Xiang could apply to the ethics committee of Beijing Anding Hospital for the release of the data.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Anding Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

HZ and Y-TX designed the study. XJ, WL, and LZ collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. XJ, WL, HZ, LZ, Y-TX, and TC drafted the manuscript. CN critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project for investigational new drug (2018ZX09201-014), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. Z181100001518005), and the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer JL declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with one of the authors, TC, to the handling editor.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the participants and clinicians involved in this study.

References

1. WHO Director. WHO Director-General's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://wwwwhoint/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19–11-march-2020 (accessed April 14, 2020).

2. Jouhns Hopkins University School of Medicine. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Jouhns Hopkins University (JHU). (2020). Available online at: https://gisanddatamapsarcgiscom/apps/opsdashboard/indexhtml#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 (accessed April 21, 2021).

3. Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry. (2021) 20:124–30. doi: 10.1002/wps.20806

4. Xiang YT, Yu X, Sartorius N, Ungvari GS, Chiu HF. Mental health in China: challenges and progress. Lancet. (2012) 380:1715–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60893-3

5. Xiang YT, Ng CH, Yu X, Wang G. Rethinking progress and challenges of mental health care in China. World Psychiatry. (2018) 17:231–2. doi: 10.1002/wps.20500

6. Chinese Society of Psychiatry. Expert consensus on managing pathway and coping strategies for patients with mental disorders during prevention and control of infectious disease outbreak (Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia) (in Chinese) (2020) 53:78–83. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn113661-20200219-00039

7. National Health Commission of China. 323 Patients With Severe Mental Disorders Were Diagnosed With New Coronary Pneumonia (in Chinese). Available online at: http://www.bjnews.com.cn/news/2020/02/18/691444.html (accessed February 19, 2020).

8. Rui L, Yue M, Ying-ying S. Prevalence and influencing factors of depression among relatives of mental disorder patients. Chin J Public Health. (2017) 20:81–4. doi: 10.11847/zgggws2017-33-02-20

9. Guo X, Mao Z. An analysis of anxiety and depression in the family members of the inpatients with schizophrenia (in Chinese). J Psychiatry. (2008) 21:344–6.

10. Kudva KG, El Hayek S, Gupta AK, Kurokawa S, Bangshan L, Armas-Villavicencio MVC, et al. Stigma in mental illness: perspective from eight Asian nations. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2020) 12:e12380. doi: 10.1111/appy.12380

11. Hill H, Killaspy H, Ramachandran P, Ng RMK, Bulman N, Harvey C. A structured review of psychiatric rehabilitation for individuals living with severe mental illness within three regions of the Asia-Pacific: implications for practice and policy. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2019) 11:e12349. doi: 10.1111/appy.12349

12. Li W, Reavley N. Patients' and caregivers' knowledge and beliefs about mental illness in mainland China: A systematic review. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2021) 13:e12423. doi: 10.1111/appy.12423

13. Xiang YT, Zhao YJ, Liu ZH, Li XH, Zhao N, Cheung T, et al. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: managing challenges through mental health service reform. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1741–4. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45072

14. Zhu Y, Chen L, Ji H, Xi M, Fang Y, Li Y. The risk and prevention of Novel Coronavirus pneumonia infections among inpatients in psychiatric hospitals. Neurosci Bull. (2020) 36:299–302. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00476-9

15. Gater A, Rofail D, Tolley C, Marshall C, Abetz-Webb L, Zarit SH, et al. “Sometimes it's difficult to have a normal life”: results from a qualitative study exploring caregiver burden in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Treat. (2014) 2014:368215. doi: 10.1155/2014/368215

16. Van Cutsem J, Marcora S, De Pauw K, Bailey S, Meeusen R, Roelands B. The effects of mental fatigue on physical performance: a systematic review. Sports Med. (2017) 47:1569–88. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0672-0

17. Robinson RL, Stephenson JJ, Dennehy EB, Grabner M, Faries D, Palli SR, et al. The importance of unresolved fatigue in depression: costs and comorbidities. Psychosomatics. (2015) 56:274–85. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2014.08.003

18. Schnohr P, Marott JL, Kristensen TS, Gyntelberg F, Grønbæk M, Lange P, et al. Ranking of psychosocial and traditional risk factors by importance for coronary heart disease: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Eur Heart J. (2015) 36:1385–93. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv027

19. Franza F, Basta R, Pellegrino F, Solomita B, Fasano V. The role of fatigue of compassion, burnout and hopelessness in healthcare: experience in the time of COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatr Danubina. (2020) 32(Suppl. 1):10–4.

20. Ruiz-Fernández MD, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Ibáñez-Masero O, Cabrera-Troya J, Carmona-Rega MI, Ortega-Galán ÁM. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction, and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:4321–30. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15469

21. Sasangohar F, Jones SL, Masud FN, Vahidy FS, Kash BA. Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a high-volume intensive care unit. Anesth Analg. (2020) 131:106–11. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004866

22. Teng Z, Wei Z, Qiu Y, Tan Y, Chen J, Tang H, et al. Psychological status and fatigue of frontline staff two months after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in China: A cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. (2020) 275:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.032

23. Morgul E, Bener A, Atak M, Akyel S, Aktas S, Bhugra D, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and psychological fatigue in Turkey. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2020). doi: 10.1177/0020764020941889. [Epub ahead of print].

24. Farina N, Page TE, Daley S, Brown A, Bowling A, Basset T, et al. Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. (2017) 13:572–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.010

25. Caqueo-Urízar A, Gutiérrez-Maldonado J, Miranda-Castillo C. Quality of life in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: a literature review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2009) 7:84. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-84

26. World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL). (2012). Available online at: https://wwwwhoint/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-HSI-Rev201203 (accessed April 22, 2021).

27. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines: Geneva: World Health Organization (1992).

28. Bo HX, Li W, Yang Y, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitude toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China. Psychol Med. (2021) 51:1052–3. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720000999

29. Luo H, Lie Y, Prinzen FW. Surveillance of COVID-19 in the general population using an online questionnaire: report from 18,161 respondents in china. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2020) 6:e18576. doi: 10.2196/18576

30. Zhou J, Liu L, Xue P, Yang X, Tang X. Mental health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:574–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304

31. Oldenmenger WH, de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CC. Cut points on 0-10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Sympt Manag. (2013) 45:1083–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.007

32. Butt Z, Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, Paice JA, Peterman AH, Shevrin D, et al. Use of a single-item screening tool to detect clinically significant fatigue, pain, distress, and anorexia in ambulatory cancer practice. J Pain Sympt Manag. (2008) 35:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.040

33. Berger AM, Abernethy AP, Atkinson A, Barsevick AM, Breitbart WS, Cella D, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines cancer-related fatigue. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. (2010) 8:904–31. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0067

34. Morin CM. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press (1993). p. xvii, 238-xvii.

35. Bai C, Daihong J, Chen L, Liang L, Wang C. Reliability and validity of Insomnia Severity Index in clinical insomnia patients (in Chinese). Chin J Pract Nurs. (2018) 34:2182–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1672-7088.2018.28.005

36. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Int Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

37. Chen M, Sheng L, Qu s. Diagnostic test of screening depressive disorder in general hospital with the Patient Health Questionnaire (in Chinese). Chin Mental Health. (2015) 29:241–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2015.04.001

38. Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, Li X, Wang W, Du J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hospital Psychiatry. (2014) 36:539–44. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.021

39. Harper A, Power M, Grp W. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. (1998) 28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798006667

40. Fang JQ, Hao YA. Reliability and validity for Chinese version of WHO Quality of Life Scale (in Chinese). Chin Mental Health J. (1999) 13:203–9.

41. Xia P, Li N, Hau K-T, Liu C, Lu Y. Quality of life of Chinese urban community residents: a psychometric study of the mainland Chinese version of the WHOQOL-BREF. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2012) 12:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-37

42. The World Bank. COVID-19 to Plunge Global Economy Into Worst Recession Since World War II. (2020). Available online at: https://wwwworldbankorg/en/news/press-release/2020/06/08/covid-19-to-plunge-global-economy-into-worst-recession-since-world-war-ii (accessed September 5, 2020).

43. Hetland B, Pozehl B, Kupzyk K, Heusinkvelt J, Krabbenhoft L, Grotts E, et al. The impact of family caregiver psychophysiological characteristics on the caregiver role in the intensive care unit. Enhancing the treatment environment to improve patient and caregiver outcomes. Am Thorac Soc. (2019) 199:A4361. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2019.199.1_MeetingAbstracts.A4361

44. Lee Y, Chiou Y-J, Hung C-F, Chang Y-Y, Chen Y-F, Lin T-K, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive disorder in caregivers of individuals with parkinson disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. (2020). doi: 10.1177/0891988720933359. [Epub ahead of print].

45. Perpiñá-Galvañ J, Orts-Beneito N, Fernández-Alcántara M, García-Sanjuán S, García-Caro MP, Cabañero-Martínez MJ. Level of burden and health-related quality of life in caregivers of palliative care patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4806. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234806

46. Corfield EC, Martin NG, Nyholt DR. Co-occurrence and symptomatology of fatigue and depression. Compr Psychiatry. (2016) 71:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.08.004

47. Walker EA, Katon WJ, Jemelka RP. Psychiatric disorders and medical care utilization among people in the general population who report fatigue. J Gen Int Med. (1993) 8:436–40. doi: 10.1007/BF02599621

48. Addington A, Gallo JJ, Ford DE, Eaton WW. Epidemiology of unexplained fatigue and major depression in the community: the Baltimore ECA follow-up, 1981-1994. Psychol Med. (2001) 31:1037. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004214

49. Zimmerman M, Ellison W, Young D, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K. How many different ways do patients meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder? Compr Psychiatry. (2015) 56:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.09.007

50. Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. (2007) 3(5 Suppl.):S7–10. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.26929

51. Altevogt BM, Colten HR. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2006).

52. Groeger JA, Viola AU, Lo JCY, von Schantz M, Archer SN, Dijk D-J. Early morning executive functioning during sleep deprivation is compromised by a PERIOD3 polymorphism. Sleep. (2008) 31:1159–67. doi: 10.5665/sleep/31.8.1159

53. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub (2013).

54. Li J, Lambert CE, Lambert VA. Predictors of family caregivers' burden and quality of life when providing care for a family member with schizophrenia in the People's Republic of China. Nurs Health Sci. (2007) 9:192–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00327.x

55. Liu M, Lambert CE, Lambert VA. Caregiver burden and coping patterns of Chinese parents of a child with a mental illness. Int J Mental Health Nurs. (2007) 16:86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00451.x

56. Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH, Gould DA, Levine C, Kuerbis AN, Donelan K. When the caregiver needs care: the plight of vulnerable caregivers. Am J Public Health. (2002) 92:409–13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.3.409

57. Petrikis P, Baldouma A, Katsanos AH, Konitsiotis S, Giannopoulos S. Quality of life and emotional strain in caregivers of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Neurol. (2019) 15:77–83. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2019.15.1.77

58. Cameron JI, Franche RL, Cheung AM, Stewart DE. Lifestyle interference and emotional distress in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Cancer. (2002) 94:521–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10212

59. Voruganti L, Heslegrave R, Awad AG, Seeman MV. Quality of life measurement in schizophrenia: reconciling the quest for subjectivity with the question of reliability. Psychol Med. (1998) 28:165–72. doi: 10.1017/S0033291797005874

60. Bower JE. Cancer-related fatigue—mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2014) 11:597. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.127

61. Kluger BM, Herlofson K, Chou KL, Lou JS, Goetz CG, Lang AE, et al. Parkinson's disease-related fatigue: a case definition and recommendations for clinical research. Mov Disord. (2016) 31:625–31. doi: 10.1002/mds.26511

62. Francis T, Tomita M, Binkewicz K, Dinatale K, Anderson V, Grandolph L, et al. Effects of OT-based interventions to reduce perceived burden and depression of caregivers of older adults with dementia. Am J Occup Therapy. (2020) 74(4_Supplement_1):7411515341p1. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2020.74S1-PO3405

63. Milbury K, Li J, Weathers S-P, Mallaiah S, Armstrong T, Li Y, et al. Pilot randomized, controlled trial of a dyadic yoga program for glioma patients undergoing radiotherapy and their family caregivers. Neuro Oncol Pract. (2019) 6:311–20. doi: 10.1093/nop/npy052

64. Stuart S, Pereira XV, Chung JP. Transcultural adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy in Asia. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2021) 13:e12439. doi: 10.1111/appy.12439

Keywords: psychiatric emergency service, fatigue, quality of life, COVID-19, carers

Citation: Ji X, Li W, Zhu H, Zhang L, Cheung T, Ng CH and Xiang Y-T (2021) Fatigue and Its Association With Quality of Life Among Carers of Patients Attending Psychiatric Emergency Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 12:681318. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.681318

Received: 16 March 2021; Accepted: 10 May 2021;

Published: 22 June 2021.

Edited by:

Yanhui Liao, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Jessie Lin, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, ChinaBao-Liang Zhong, China University of Geosciences Wuhan, China

Copyright © 2021 Ji, Li, Zhu, Zhang, Cheung, Ng and Xiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu-Tao Xiang, eHl1dGx5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Chee H. Ng, Y25nQHVuaW1lbGIuZWR1LmF1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Xiao Ji1†

Xiao Ji1† Wen Li

Wen Li Ling Zhang

Ling Zhang Teris Cheung

Teris Cheung Chee H. Ng

Chee H. Ng Yu-Tao Xiang

Yu-Tao Xiang