95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 09 April 2021

Sec. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643234

This article is part of the Research Topic Advances in Social Cognition Assessment and Intervention in Autism Spectrum Disorder View all 22 articles

Background: Several studies have reported contradictory results regarding the benefits of music interventions in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), including autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Methods: We performed a systematic review according to the PRISMA guidelines. We searched the Cochrane, PubMed and Medline databases from January 1970 to September 2020 to review all empirical findings, except case reports, measuring the effect of music therapy on youths with ASD, intellectual disability (ID), communication disorder (CD), developmental coordination disorder (DCD), specific learning disorder, and attention/deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Results: Thirty-nine studies (N = 1,774 participants) were included in this review (ASD: n = 22; ID: n = 7; CD and dyslexia: n = 5; DCD: n = 0; ADHD: n = 5 studies). Two main music therapies were used: educational music therapy and improvisational music therapy. A positive effect of educational music therapy on patients with ASD was reported in most controlled studies (6/7), particularly in terms of speech production. A positive effect of improvisational music therapy was reported in most controlled studies (6/8), particularly in terms of social functioning. The subgroup of patients with both ASD and ID had a higher response rate. Data are lacking for children with other NDDs, although preliminary evidence appears encouraging for educational music therapy in children with dyslexia.

Discussion: Improvisational music therapy in children with NDDs appears relevant for individuals with both ASD and ID. More research should be encouraged to explore whether oral and written language skills may improve after educational music therapy, as preliminary data are encouraging.

The new section of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) in the DSM-5 encompasses psychiatric disorders with an onset in early childhood (1). The clinical expression of all NDDs is closely related to the child's own developmental dynamics. Several mechanisms may explain the structural abnormalities in brain structures reported in most patients with NDDs: consequences of perinatal risk factors, abnormal brain maturation, and consequences of a lack of opportunity to use functional areas. The NDD section of the DSM-5 includes autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual disability (ID), attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity (ADHD), developmental coordination disorders (DCD), communication disorders (CD) (including language, phonological, and pragmatic social communication disorders, and stuttering) and specific learning disabilities (SLDs) (characterized by persistent difficulties in learning the fundamental academic skills of reading, writing or mathematics).

ASD is characterized by two main dimensions: a deficit in communication and reciprocal social interactions and a restriction of interests with repetitive and stereotypical behaviors (1). In addition to the core symptoms of ASD, other developmental dimensions are worth investigating to document associated problems (intellectual functioning, sensory modulation impairments, language difficulties, motor skills, attentional difficulties, emotional regulation, associated medical condition (e.g., seizures), eating, and sleeping) (2). Such integrative approaches help clinicians provide tailored interventions. Three categories of therapeutic interventions for children with ASD have been distinguished:

1. Pure behavioral methods [e.g., Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)] are based on a comprehensive analysis of children's behaviors to promote well-adapted behaviors based on positive reinforcement. Some behavioral methods are based on the child's preferences, such as pivotal response training (PRT). Some of these programs involve parents, such as the Son Rise program, which occurs at home (3, 4).

2. Developmental methods aim to promote the development process (e.g., floor time or the Early Start Denver Model—ESDM). In these programs, the therapist starts from the child's interests and follows their initiatives to promote communication performance using the skills of imitation and synchrony. Some of these methods include behavioral techniques, such as ESDM (5, 6).

3. Mixed methods (e.g., Treatment and Education of Autistic and Communication Handicapped Children—TEACCH) aim to reduce problematic behaviors in a behavioral approach while considering the child's specific developmental level. Parental guidance is an essential aspect of these programs to allow the child's emerging competences to be generalized into his natural environment (7).

These methods target the primary difficulties experienced by patients with ASD in social interaction and communication, in particular joint attention, imitation, synchrony, emotional sharing and symbolic play. The predictors of the treatment response of patients with ASD to these interventions include intensive interventions (at least 3–4 h per day), interventions provided at an early age, intervention tailored to the patient's developmental needs, interventions promoting family inclusion and spontaneous communication with peers, and interventions with repeated assessment of therapeutic goals based on the child's progress (8).

Children with ID require a global approach with interventions promoting cognitive skills and autonomy. Most authors recommend that a regular multidimensional evaluation of cognitive, educational, socioemotional, and adaptive skills throughout life. It usually provides a better understanding of how individuals with ID function (9). The goal regarding treatment approach is to contribute toward the planning of more appropriate strategies for learning, care, and support, leading to a better quality of life and participation in society. Specific programs are delivered according to children's developmental levels, family burdens and etiological factors (e.g., antiepileptic drug in case of seizures). Interventions provided at school or specialized institutions play a key role in enhancing pedagogic and academic achievements. Specific intervention form speech therapists, occupational therapists, reading specialists may also target a specific function (9).

For other NDDs, therapeutic approaches directly target the impaired function: speech therapists for children with communication disorders, reading specialists for children with written language difficulties, and occupational therapists for children with motor disorders. Children with ADHD may benefit from attention remediation and cognitive therapy. ADHD is also the only NDD for which effective medications are available (e.g., methylphenidate).

From the biblical scene of David playing harp to the Gnaoua ritual in Maghreb, anecdotal testimonies of the healing effect of music are reported in all cultures. In the history of psychiatry, music was a component of the moral treatment advocated by Pinel in the eighteenth century. Since music remains one aspect of the milieu and occupational therapy of patients receiving ambulatory care for chronic mental health conditions. It is after the Second World War that music therapy became a structured psychotherapy in North America to treat veteran (10). Nordoff and Robbins (11) created a structured method known as “creative musical therapy” based on the principle of a relational component of music.

Among music therapies, a traditional distinction exists between receptive music therapy techniques (based on listening) and active music therapy techniques (based on sound production by voice, body percussion, or use of instruments). This distinction has been questioned because listening may also involve an active component. Current research usually distinguishes three techniques: music listening, interactive music therapy and improvisational music therapy (12). Interactive music therapy is essentially a structured method including techniques for educational purposes or musical games. For clarity, in this article, the term educational music therapy will be used for this category. Improvisational music therapy uses children's music production to promote spontaneous non-verbal communication. As the distinction between these categories is somewhat arbitrary, a mixed method category also exists.

The particular interest in music of patients with autism was already noted in the historical description by Kanner (13). He observed that some non-verbal patients are able to sing or hum. Some other patients are able to recognize complex melodies. Several reasons for the hypothesis that music therapy represents a useful adjunct treatment in youths with autism have been documented. Music therapy is regarded as a way of promoting preverbal communication through the improvement of joint attention, motor imitation, and ultimately synchronous rhythm (14). Music therapy has also been used to enhance some cognitive functions, such as attention or memory (15). As impairments in social interactions are also often reported at some point in youths with other NDDs, the effects of music therapy are worth investigating in patients with these other conditions. In this review, we aimed to review the evidence examining the use of music therapy in youths with ASD and/or other NDDs.

The systematic review was conducted according to the recommendations outlined in the PRISMA guidelines (16). Titles and abstracts were scanned for relevance. Full texts were ordered in cases of uncertainty. Reference lists of retrieved systematic reviews were checked. All full texts were assessed for eligibility. Any original study was eligible for inclusion in this review. Abstracts, editorials, and case series with only one evaluation were excluded. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were examined for references but not included.

We included studies that measured the effect of music therapy intervention (music listening, interactive or educational music therapy, improvisational music therapy, or mixed method), in children or adolescents (participants aged up to 18 years), diagnosed with ASD and/or another NDD. Other NDD were ADHD, ID, DCD, CD, and SLD. Exclusion criteria were: (1) study without outcomes derived from a distinct subgroup of subjects with ASD and/or other NDD; (2) study reporting pooled results without distinction between adults and youths; (3) study that did not provide new empirical data or without objective assessment of clinical outcome; (4) study reporting the effect of music therapy in neurological/neurodevelopmental disorder different from the list mentioned above (e.g., epilepsy).

Relevant articles were obtained by searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed and Medline databases. Each database was searched from January 1970 to September 2020. In addition, we hand searched reference lists of identified articles and pertinent reviews for additional studies. Only studies in English, French or German were included. References from the reviewed articles were also screened to find more articles of interest. We used the following search terms: (“music” OR “music therapy”) AND (“autism” OR “pervasive developmental disorder” OR “intellectual disability” OR “dyslexia” OR “written language disorder” OR “attention deficit disorder” OR “hyperkinetic disorder” OR “communication disorder” OR “oral language disorder” OR “specific learning disorder” OR “social relationship” OR “social skills” OR “social responsive behaviours” OR “social motivation” OR “communication” OR “nonverbal” OR “joint attention”). The systematic review yielded 2,778 hits, and 2,725 hits were excluded based on the information in the title or abstract. The full texts of the remaining 54 hits were critically reviewed, leading to the exclusion of another 15 articles because they were only reviews or comments and no new original data were included; alternatively, the research did not present objective outcomes or did not present music therapy intervention or child or adolescent population. One full-text was not found (17). Thirty-nine studies were included: 22 studies of children with ASD, 7 studies of children with ID, 5 studies of children with ADHD, and 5 studies of children with CD and SLD (dyslexia). No study was found for children with DCD, but one ASD study evaluates motor impairment associated with ASD (18). Figure 1 summarizes the PRISMA flowchart of the study.

Data and information were independently extracted from each study by the first two authors. In cases of disagreement, a consensus approach was adopted that included the third author. For each study under review, the year of publication and references were extracted. In each report, we collected the following information: (i) description of the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants (age, gender, and method of diagnosis), (ii) description of the interventions (method of music therapy, duration, frequency, and setting), and (iii) clinical outcomes (effect of the intervention and possible side effects). Considering the disparity in music therapy methods used for children with ASD, the results were presented according to the category of music therapy, i.e., educational music therapy or improvisational music therapy. Only one study included in our review offered a music listening technique, but results were not presented in tables due to severe methodological problems (19). The diverse statistical methods and measurement practices used across studies did not allow for the calculation of pooled effect sizes, such as those used in meta-analyses.

An evaluation of the different risk of bias was performed by the first author according to the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool (20) and the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) (21). Results are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

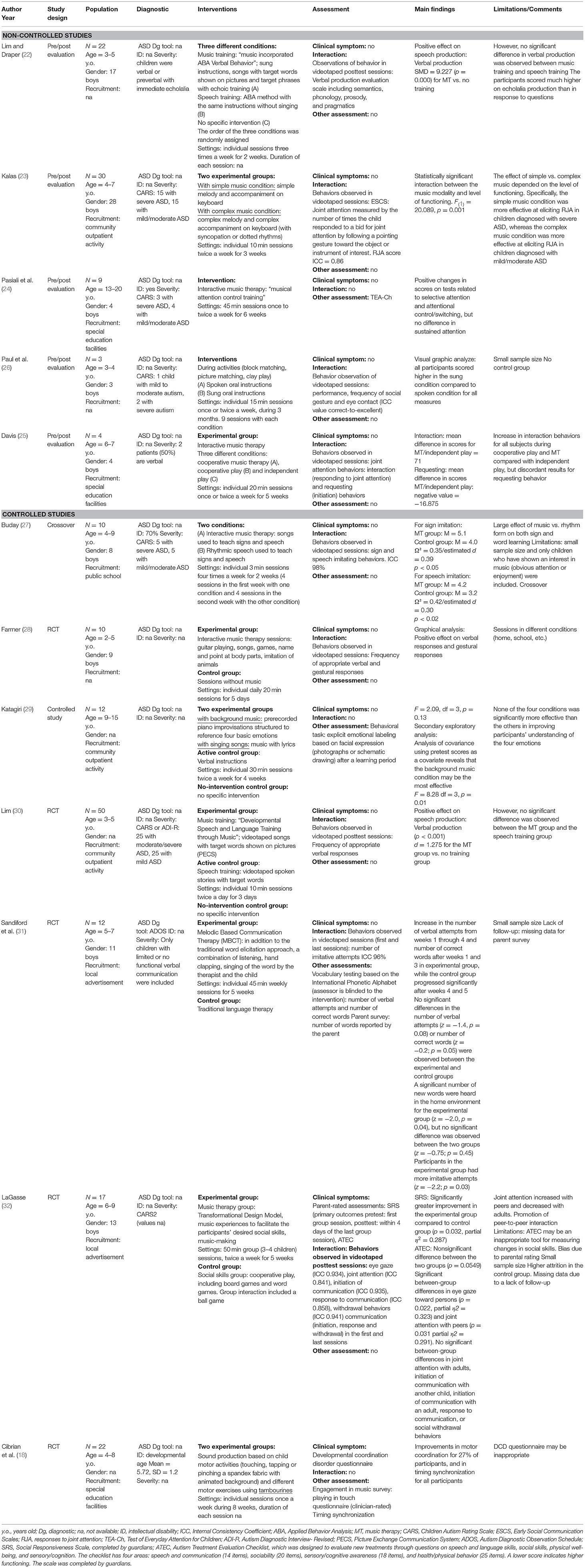

Ten studies evaluated the effects of educational music therapy in youths with ASD: five uncontrolled studies (22–26) and seven controlled studies (18, 27–32). They are all summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Studies assessing educational musicotherapy in patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Only one study examined the effect of an educational music therapy intervention on the severity of autistic symptoms (32). The authors observed a small effect of the intervention on the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) score (partial η2 = 0.29) within the 4 days following the last session. Other studies assessed the effect of educational music therapy on other developmental dimensions. Four studies evaluated the benefit of educational music therapy on joint attention (23, 25, 26, 32). Joint attention was assessed with videos of adult-child interactions by collecting data on pointing behaviors (23, 32), direction of gaze toward an object/person (26, 32), and spontaneous reactions or in response to adults' behaviors (25, 26). None of these studies reported a statistically significant effect of these interventions on the joint attention of children with ASD (23, 25, 26, 32). Paul et al. (26) suggests a positive effect of sung directives during different activities compared to spoken directives on graphic analyzes. Pasiali et al. (24) assessed the effect of music therapy on different components of attention using TEA-Ch (Test of Everyday Attention for Children) in youths with ASD. The authors reported that youths with ASD who received music therapy achieved higher performance in selective and divided attention than at baseline; however, no change in sustained attention was observed before and after the intervention. Another study evaluated the effect of musical therapy on the recognition of emotions in youths with ASD. Katagiri (29) examined whether a piano melody congruent with the emotional valence of a facial expression presented with a picture or a drawing influenced the performance on an emotional recognition task. The authors did not obtain any significant results.

Cibrian et al. (18) evaluated two different music therapy interventions in the motor impairments of young patients with ASD. The reported outcome suggests a positive effect of music therapy on coordination and timing synchronization.

Finally, five studies evaluated the benefits of educational music therapy on language and communication skills (22, 27, 28, 30, 31). In these studies, language was assessed using different methods: list of new words learned (27, 28, 30, 31), spontaneous verbal production (22), and number of words reported by parents (31). Four of five studies showed statistically significant results (22, 27, 28, 30). According to Buday (27), youths with ASD who learned a word list with rhythmic music achieved better results than youths who participated in sessions using the rhythm alone (d = 0.30). Farmer (28) observed a tendency in children with ASD who received an intervention with structured musical games to express more appropriate verbal responses than children who received an intervention with non-musical games. Lim (30) showed that the use of music videos facilitated the learning of target words (d = 1.28) in children with autism compared to those in a control group that did not receive the intervention. This difference, however, was not statistically significant compared to the group receiving a language intervention based on non-music videos (d = 1.14). The same team showed that singing instructions inspired by the ABA method exerted a positive effect on learning target words compared to a control group that did not receive any intervention. This difference was again not statistically significant compared to the group receiving the language intervention (22). Sandiford, Mainess (31) did not report any significant difference in the rate of new words learned between the group of children with ASD who received an intervention using mixed music therapy methods (singing, listening to music and rhythmic hand clapping) compared to children who underwent classical speech therapy sessions. However, an analysis of learning trajectories showed faster progress in the group with music therapy.

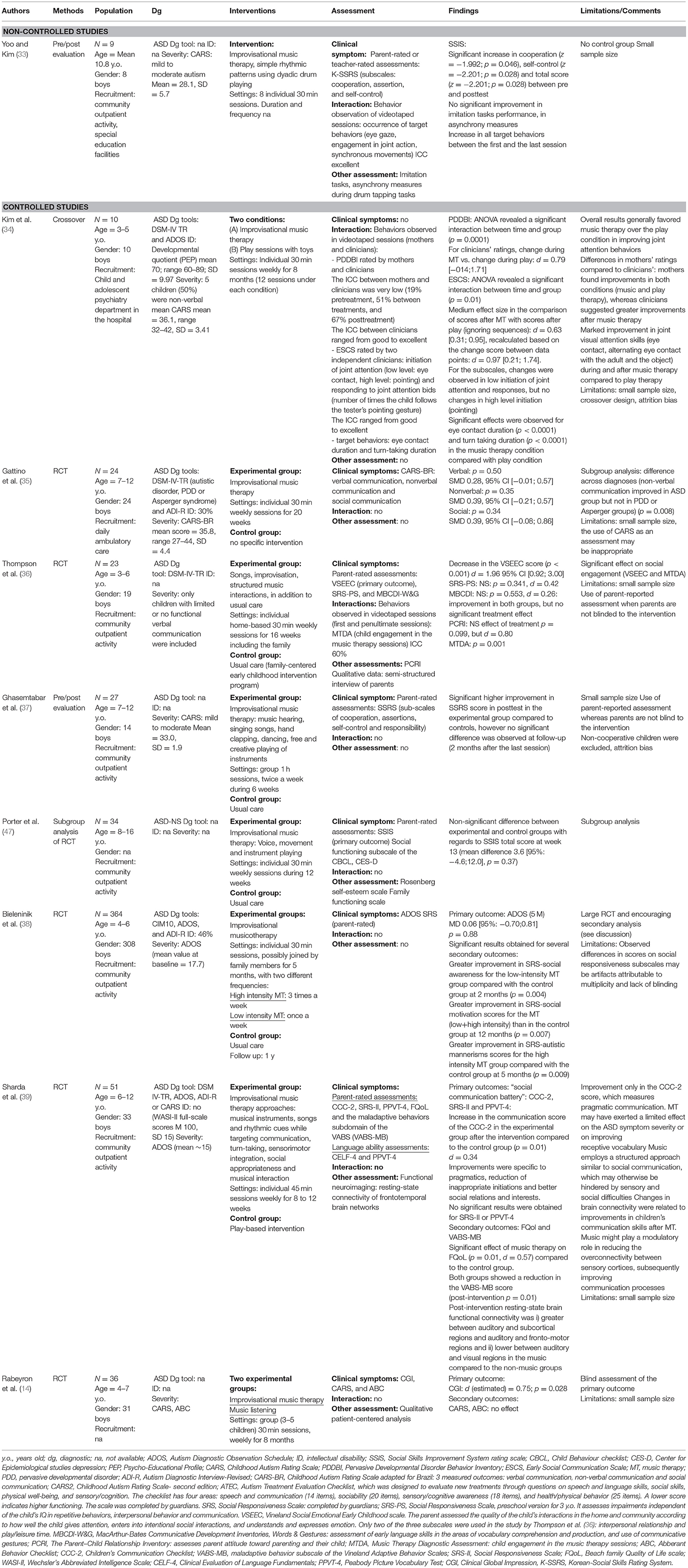

One uncontrolled study (33) and eight controlled studies (14, 34–39, 47) evaluated the effect of improvisational music therapy on youths with ASD (Table 2). Thompson, McFerran (36) measured the effects of home-based improvisational music therapy sessions including family members on the severity of clinical symptoms and the overall level of functioning of youths with ASD. The authors noted that the youths who participated in music therapy sessions had a lower score on the Vineland scale (d = 1.96) than the control group who received the current standard of care. No difference was observed in scores on the SRS scale (secondary outcome) between the two groups. Sharda et al. (39) described positive effects of improvisational music therapy sessions compared to games sessions on the level of pragmatic of language (Children's Communication Checklist-2, CCC-2 score) and the quality of life, but no effect on the other main primary outcomes (SRS score and score on the Peabody vocabulary test). Rabeyron et al. (14) documented a higher clinical improvement in the primary outcome (change in Clinical Global Impression, CGI, score, d = 0.75) of youths who participated in improvisational music therapy sessions than youths who received an intervention with listening music therapy sessions. The changes observed in the secondary outcomes (i.e., Childhood Autism Rating Scale, CARS, and Autism Behavior Checklist, ABC, scores) were not significantly different between the two groups after the music therapy sessions. Kim et al. (34) observed a positive effect of music therapy sessions on joint attention and prosocial behaviors. Impact of improvisational music therapy on social skills were contradictory: two studies (33, 37) showed an improvement of the Social Skills Improvements System Rating Scale after music therapy sessions, while no significant differences were found in another study (47). Gattino et al. (35) did not find any statistically significant difference in the CARS score between the group receiving music therapy and the group receiving the usual treatment.

Table 2. Studies assessing improvisational music therapy in patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The study by Bieleninik et al. (38) deserves more attention, as the study included 364 young patients with ASD in 9 different country sites. They did not observe a significant difference in the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) or SRS score (primary outcomes) at 2, 5, and 12 months between the three arms: treatment as usual, non-intensive music therapy, and intensive music therapy. However, they identified some differences in scores for SRS subscales, with a greater improvement in the score for the social motivation subscale of the music therapy group at 12 months and in the score for the autistic mannerisms subscale at 5 months. In addition, the authors presented at a congress unpublished data stressing that the subgroups of subjects with both ASD and ID had a higher response rate for the primary outcome ADOS (risk ratio = 1.43 [95% CI: 1–2.05], p = 0.049).

Five non-controlled studies (40–44) and two controlled studies (45, 46) evaluated the effect of music therapy on youths with ID (Table 3). Two studies showed a positive effect of music therapy sessions on parent-child interactions, with increased spontaneous demands by the child and adapted parental responses (41, 43), more synchronous behaviors between parents and children (43), and an improvement in parents' mental health (41). Zyga et al. (44) also reported an improvement in the socioemotional abilities of children who participated in mixed music therapy sessions, including singing, dancing and theater. Mendelson et al. (42) documented a positive effect of educational music therapy sessions delivered in the classroom on peer interactions during the sessions. However, this effect was observed only in subjects who participated in a 15 week program and not in participants who received a shorter 7 week intervention.

Regarding controlled studies, Aldridge et al. (45) showed a non-significant trend for a positive effect of improvisational music therapy sessions on a global measure of the developmental level in children with ID. Specifically, the authors stressed the importance of the improvement in hand-eye coordination. Duffy and Fuller (46) did not detect a significant difference in the rate of progress in terms of imitation, vocalization, initiation of interaction, eye contact and turn-taking between children who received music therapy and those who did not.

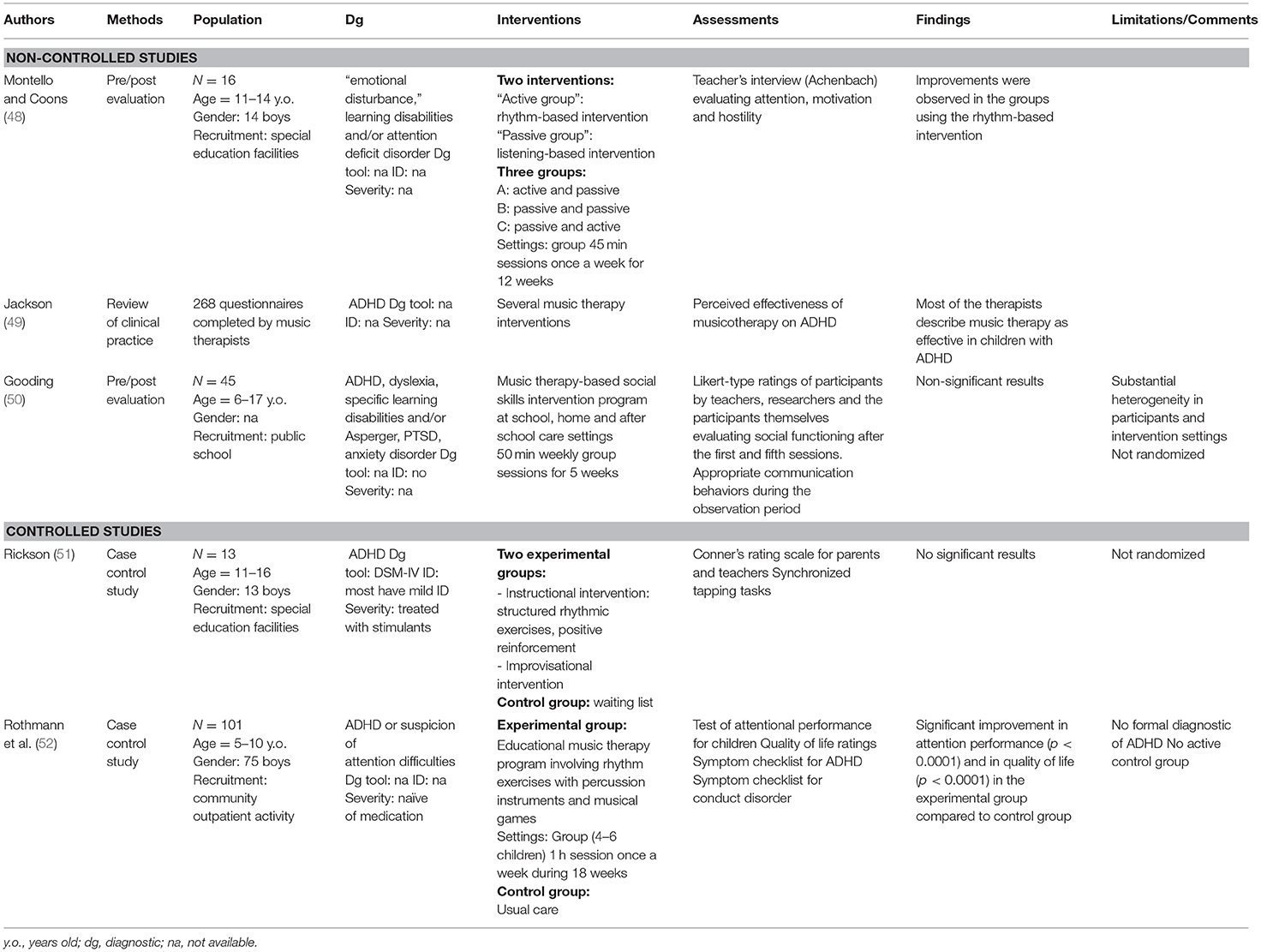

Three non-controlled studies (48–50) and two controlled study (51, 52) evaluated the effect of music therapy on youths with ADHD (Table 4). These studies presented significant methodological biases. The largest study (n = 268) was based on a questionnaire administered to music therapists (34). Rothmann et al. (52) showed significant improvements in attentional performance tests and in quality of life after music therapy among children with suspected ADHD compared to those who received usual care. Montello and Coons (48) suggested that school-based educational music therapy sessions using rhythms are associated with increased attention and motivation and decreased hostility in children with behavioral problems based on teacher reports.

Table 4. Studies assessing musicotherapy in youths with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

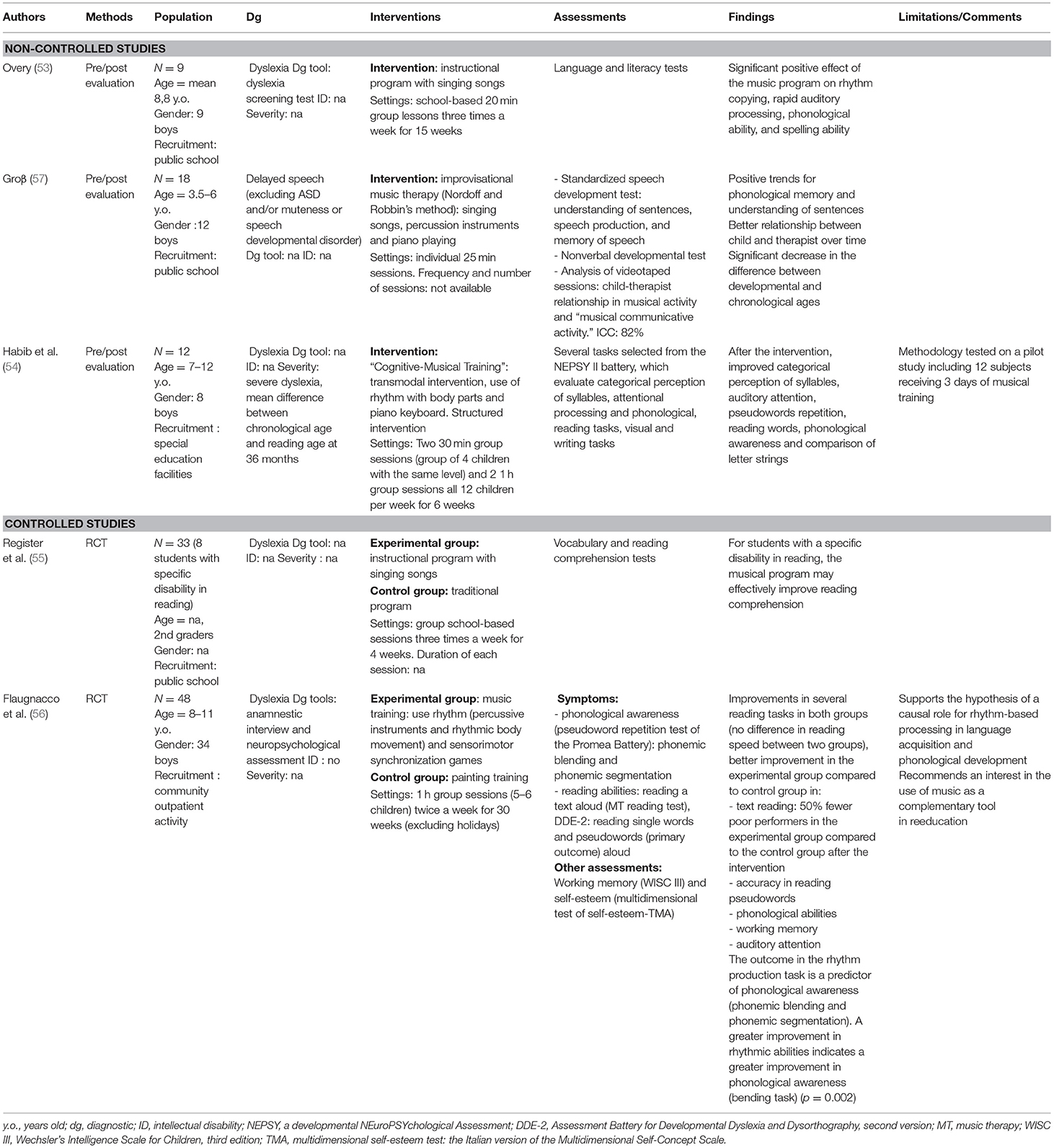

Four studies were conducted in youths with dyslexia, and one study was conducted in youths with language delay (Table 5). Two non-controlled studies examined the effect of educational music therapy on children with dyslexia (53, 54). Overy (53) reported a positive effect of school-based music therapy sessions on reading competence in nine children with dyslexia. Habib et al. (54) documented an improvement in several domains of written language competence in 12 children with dyslexia after music therapy sessions, such as phonological perception, pseudoword repetition, word reading, and auditory attention.

Table 5. Studies assessing musicotherapy in children with communication/oral and written language disorder.

Two randomized controlled studies were conducted to document the effect of educational music therapy on children with dyslexia. Register et al. (55) observed an improvement in vocabulary and reading comprehension test scores in children with written language difficulties who participated in school-based music therapy sessions compared to children who participated in a traditional program for learning difficulties. Flaugnacco et al. (56) found that children with dyslexia who participated in school-based music therapy group sessions presented increased phonological awareness and reading skills (for accuracy but not speed) compared to children who had participated painting sessions during the same time. The authors noted that rhythm perception during the sessions was a predictor of a positive treatment response.

Finally, one non-controlled study (57) evaluated the effect of improvisational music therapy on 18 children with language delay. The authors observed a significant increase in developmental age (in particular phonological memory and sentence understanding) after a 6 week individual improvisational music therapy program.

Considering the diversity of music therapy approaches, improvisational and educational music therapy programs provided to youths with ASD and other NDDs were distinguished. Regarding educational music therapy, our findings support a positive but small effect of educational music therapy on children with NDDs, particularly patients with ASD and/or ID. Two major limitations in the results obtained for children with ASD are noted. First, only one study used core ASD symptoms as a primary outcome (32), leading to difficulties in generalizing the results. Second, the results for improving joint attention are mixed. The determination of whether educational music therapy interventions are ineffective or whether these effects are difficult to demonstrate is challenging. Indeed, joint attention measures are rarely standardized, questioning their validity.

Studies evaluating the effect of educational music therapy on language and communication skills in children with ASD reported three main results. First, a significant effect on learning target words based on imitation skills was observed. Second, a study showed that educational music therapy sessions were associated with improvements in several components of oral language (phonology, semantics, prosody, and pragmatics) (30). Third, a positive effect was observed for the music therapy group compared to the group without treatment, but not for the active control group using non-musical techniques.

Regarding improvisational music therapy, we found few empirical findings supporting a positive effect of improvisational music therapy sessions on youths with NDD, but some findings appear interesting for children with ASD and/or ID. The most methodologically robust study conducted by Bieleninik, Geretsegger (38) did not report a significant improvement in the primary outcome (ADOS) and a positive effect of music therapy sessions only on a few secondary outcomes. However, they observed a significant effect on the subgroup of participants with ASD and ID. In a secondary analysis based on what aspects of improvisational music therapy predicted an improvement, the authors performed a microanalysis of the video therapy sessions and showed that a high level of relational adjustment between the child and the therapist was a strong predictor of positive outcomes (58). These authors concluded that the intervention is more effective when the therapist adopts a relational pattern similar to the child's pattern. A similar hypothesis was formulated by Rainey Perry (40) based on their work with children with severe and multiple disabilities. The therapist uses a relational mode that fits the child's “communication profile” to provide the child opportunities to respond to interactions.

The choice of the primary outcomes in the reviewed studies should be discussed. In the study conducted by Bieleninik, Geretsegger (38), the primary outcome was the social affect score of the ADOS at 5 months (i.e., encompassing problematic reciprocal social interactions and communication). However, the ADOS is a diagnostic tool that was not specifically designed to assess variations in clinical severity over time. However, the studies that used clinical scales such as the SRS or the CARS to track changes in the severity of autistic symptoms did not present significant findings. However, several reviewed studies showed a positive effect of improvisational music therapy sessions on children with ASD or/and ID using measures of subjective clinical improvement (e.g., CGI) and the level of global functioning or quality of life (14, 36, 39). Finally, music interventions including family members exerted a stronger effect than other types of interventions for youths with ID (36). This finding is a possible argument supporting the inclusion of family in improvisational music intervention sessions in youths with ID. However, so far, no direct comparison between therapy sessions including family members or not has been conducted to test this hypothesis.

Regarding children with NDDs other than ASD and/or ID, two observations can be made from the preliminary data on the effect of musicotherapy. First, a positive trend for music therapy sessions using rhythm on the written language of children with dyslexia was reported. However, the number of studies and the total number of children included (n = 120) remain limited. Second, the quality of evidence supporting a positive effect of music therapy on children with ADHD remains poor.

Currently, many limitations exist regarding the studies included in the current review. The main limitation of this review is related to the methodological quality of the studies analyzed, with small sample sizes and wide age ranges (Supplementary Table 1). Most studies had a non-controlled design, and when a control group existed the allocation of the treatment was not necessarily randomized (e.g., case-control study) questioning the impact of possible confounding biases. Second, music therapy interventions are extremely heterogeneous, particularly in the context of educational music therapy, making cross-study comparisons difficult and meta-analysis calculations invalid. Third, the primary outcomes used varied widely between studies. A lack of information about the measures of interaction, if any, contributes to the heterogeneity of the studies. Associated evaluations of clinical dimensions have rarely been performed. In particular, no study included a standardized assessment of anxiety symptoms, while previous reports show a benefit of music therapy sessions in patients with these symptoms (59). Finally, the conclusion of this review may be influenced by the process of study selection and the limitations inherent to the search strategy (e.g., lacking of keywords, studies in other language, publication bias).

How useful is the addition of music therapy sessions to the traditional care of children with NDDs? A number of methodological biases prevents us from generating any firm conclusions based on the studies reviewed. Among the different combinations of music therapy sessions and clinical characteristics of the patients tested, a stronger effect was observed for the use of improvisational music therapy in children with both ASD and ID (22, 24, 31). While these interventions failed to significantly reduce the level of autistic symptoms in most published studies, several authors reported a positive effect on other clinical dimensions (22), on the overall level of functioning (e.g., CGI) (24), and on quality of life (39, 41). Notably, the effect was enhanced when family members were included in sessions (36, 41, 43).

Further studies would be particularly inspired to document the potential mediators of the therapeutic effects (e.g., age of the participants; cognitive characteristics), in addition to the measurements of clinical symptoms and level of functioning (58). Among other hypotheses, music therapy sessions might exert a positive effect by increasing the quantity and quality of adult-child interactions. The child-therapist relation might be regarded as an “experimental” relation for children, where he/she learns to attune his/her behaviors to adult behaviors. Another promising finding that deserves attention is the positive effect of educational music therapy on children with dyslexia, but more research is needed to conclude any definitive positive effect. For children with other NDDs, more substantial studies are needed before a conclusion can be made on the value of their use.

DC and HM-B designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HM-B, XB, and FV performed the study search. HM-B and XB extracted the data from the studies. FV checked the data for consensus agreement. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

The systematic review was founded by the Centre d'Activités et de Recherche en Psychiatrie Infanto-Juvénile (CARPIJ) and by the Fond de Dotation Entreprendre pour Aider (EpA).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643234/full#supplementary-material

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

2. Xavier J, Bursztejn C, Stiskin M, Canitano R, Cohen D. Autism spectrum disorders: an historical synthesis and a multidimensional assessment toward a tailored therapeutic program. Res Autism Spect Disord. (2015) 18:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.06.011

3. Reichow B, Hume K, Barton EE, Boyd BA. Early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 5:Cd009260. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009260.pub3

4. Virués-Ortega J. Applied behavior analytic intervention for autism in early childhood: meta-analysis, meta-regression and dose-response meta-analysis of multiple outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. (2010) 30:387–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.008

5. Rogers SJ, Dawson G. Early start denver model for young children with autism: promoting language, learning and engagement. J Autism Dev Disord. (2011) 41:978–80. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1041-8

6. Ospina MB, Krebs Seida J, Clark B, Karkhaneh M, Hartling L, Tjosvold L, et al. Behavioural and developmental interventions for autism spectrum disorder: a clinical systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2008) 3:e3755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003755

7. Virues-Ortega J, Julio FM, Pastor-Barriuso R. The TEACCH program for children and adults with autism: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Clin Psychol Rev. (2013) 33:940–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.005

8. Narzisi A, Costanza C, Umberto B, Muratori F. Non-pharmacological treatments in autism spectrum disorders: an overview on early interventions for pre-schoolers. Curr Clin Pharmacol. (2014) 9:17–26. doi: 10.2174/15748847113086660071

9. Szymanski L, King BH. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with mental retardation and comorbid mental disorders. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Working Group on Quality Issues. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1999) 38(Suppl. 12):5–31s. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(99)80002-1

10. Gaston ET. Music in Therapy. New York, NY: Sixth Book of Proceedings of the National Association for Music Therapy (1968).

11. Nordoff P, Robbins C. Creative Music Therapy: Individualized Treatment for the Handicapped Child. New York, NY (1977).

12. Lecourt É. Chapitre 3. La Musicothérapie. Les Art-Thérapies. Paris: Armand Colin (2017). p. 75–119.

14. Rabeyron T, Saumon O, Dozsa N, Carasco E, Bonnot O. De la Médiation musicotherapique dans la prise en charge des troubles du spectre autistique chez l'enfant : evaluation, processus et modelisation. La Psychiatr l'enfant. (2019) 62:147–71. doi: 10.3917/psye.621.0147

15. Ho YC, Cheung MC, Chan AS. Music training improves verbal but not visual memory: cross-sectional and longitudinal explorations in children. Neuropsychology. (2003) 17:439–50. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.17.3.439

16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

17. Thomas E, Egnal NS, van Eeden F, Bond A. The effects of music therapy on a group of institutionalised mentally retarded boys. S Afr Med J. (1974) 48:1723–8.

18. Cibrian FL, Madrigal M, Avelais M, Tentori M. Supporting coordination of children with ASD using neurological music therapy: a pilot randomized control trial comparing an elastic touch-display with tambourines. Res Dev Disabil. (2020) 106:103741. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103741

19. Lanovaz MJ, Sladeczek IE, Rapp JT. Effects of music on vocal stereotypy in children with autism. J Appl Behav Anal. (2011) 44:647–51. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-647

20. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. (2016) 355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919

21. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

22. Lim AH, Draper E. The effects of music therapy incorporated with applied behavior analysis verbal behavior approach for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Music Ther. (2011) 48:532–50. doi: 10.1093/jmt/48.4.532

23. Kalas A. Joint attention responses of children with autism spectrum disorder to simple versus complex music. J Music Ther. (2012) 49:430–52. doi: 10.1093/jmt/49.4.430

24. Pasiali V, LaGasse AB, Penn SL. The effect of musical attention control training (MACT) on attention skills of adolescents with neurodevelopmental delays: a pilot study. J Music Ther. (2014) 51:333–54. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thu030

25. Davis M. The Effect of Music Therapy on Joint Attention Skills in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. University of Kansas (2016).

26. Paul A, Sharda M, Menon S, Arora I, Kansal N, Arora K, et al. The effect of sung speech on socio-communicative responsiveness in children with autism spectrum disorders. Front Hum Neurosci. (2015) 9:555. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00555

27. Buday EM. The Effects of Signed and Spoken Words Taught with Music on Sign and Speech Imitation by Children with Autism. J Music Ther. (1995) 32:189–202. doi: 10.1093/jmt/32.3.189

28. Farmer KJ. The Effect of Music vs. Nonmusic Paired With Gestures on Spontaneous Verbal and Nonverbal Communication Skills of Children With Autism Between the Ages 1-5. Florida State University (2003).

29. Katagiri J. The effects of background music and song texts ont he emotional understanding of children with autism. J Music Ther. (2009) 46:15–31. doi: 10.1093/jmt/46.1.15

30. Lim AH. Effect of “Developmental speech and language training through music” on speech production in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Music Ther. (2010) 47:2–26. doi: 10.1093/jmt/47.1.2

31. Sandiford GA, Mainess KJ, Daher NS. A pilot study on the efficacy of melodic based communication therapy for eliciting speech in nonverbal children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. (2013) 43:1298–307. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1672-z

32. LaGasse AB. Effects of a music therapy group intervention on enhancing social skills in children with autism. J Music Ther. (2014) 51:250–75. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thu012

33. Yoo GE, Kim SJ. Dyadic drum playing and social skills: implications for rhythm-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Music Ther. (2018) 55:340–75. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thy013

34. Kim J, Wigram T, Gold C. The effects of improvisational music therapy on joint attention behaviors in autistic children: a randomized controlled study. J Autism Dev Disord. (2008) 38:1758–66. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0566-6

35. Gattino GS, Riesgo RdS, Longo D, Leite JCL, Faccini LS. Effects of relational music therapy on communication of children with autism: a randomized controlled study. Nordic J Music Ther. (2011) 20:142–54. doi: 10.1080/08098131.2011.566933

36. Thompson GA, McFerran KS, Gold C. Family-centred music therapy to promote social engagement in young children with severe autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled study. Child Care Health Dev. (2014) 40:840–52. doi: 10.1111/cch.12121

37. Ghasemtabar SN, Hosseini M, Fayyaz I, Arab S, Naghashian H, Poudineh Z. Music therapy: an effective approach in improving social skills of children with autism. Adv Biomed Res. (2015) 4:157. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.161584

38. Bieleninik L, Geretsegger M, Mossler K, Assmus J, Thompson G, Gattino G, et al. Effects of improvisational music therapy vs. enhanced standard care on symptom severity among children with autism spectrum disorder: the time-a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2017) 318:525–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9478

39. Sharda M, Tuerk C, Chowdhury R, Jamey K, Foster N, Custo-Blanch M, et al. Music improves social communication and auditory-motor connectivity in children with autism. Transl Psychiatry. (2018) 8:231. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0287-3

40. Rainey Perry MM. Relating improvisational music therapy with severely and multiply disabled children to communication development. J Music Ther. (2003) 40:227–46. doi: 10.1093/jmt/40.3.227

41. Williams KE, Berthelsen D, Nicholson JM, Walker S, Abad V. The effectiveness of a short-term group music therapy intervention for parents who have a child with a disability. J Music Ther. (2012) 49:23–44. doi: 10.1093/jmt/49.1.23

42. Mendelson J, White Y, Hans L, Adebari R, Schmid L, Riggsbee J, et al. A preliminary investigation of a specialized music therapy model for children with disabilities delivered in a classroom setting. Autism Res Treat. (2016) 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2016/1284790

43. Yang YH. Parents and young children with disabilities: the effects of a home-based music therapy program on parent-child interactions. J Music Ther. (2016) 53:27–54. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thv018

44. Zyga O, Russ SW, Meeker H, Kirk J. A preliminary investigation of a school-based musical theater intervention program for children with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil. (2018) 22:262–78. doi: 10.1177/1744629517699334

45. Aldridge D, Gustroff D, Neugebauer L. A pilot study of music therapy in the treatment of children with developmental delay. Comple. Ther. Med. (1995) 3:197–205. doi: 10.1016/S0965-2299(95)80072-7

46. Duffy B, Fuller R. Role of music therapy in social skills development in children with moderate intellectual disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2001) 13:77–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3148.2000.00011.x

47. Porter S, McConnell T, McLaughlin K, Lynn F, Cardwell C, Braiden H-J, et al. Music therapy for children and adolescents with behavioural and emotional problems: a randomised controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. (2017) 58:586–94. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12656

48. Montello L, Coons EE. Effects of active versus passive group music therapy on preadolescents with emotional, learning, and behavioral disorders. J Music Ther. (1998) 35:49–67. doi: 10.1093/jmt/35.1.49

49. Jackson NA. A survey of music therapy methods and their role in the treatment of early elementary school children with ADHD. J Music Ther. (2003) 40:302–23. doi: 10.1093/jmt/40.4.302

50. Gooding LF. The effect of a music therapy social skills training program on improving social competence in children and adolescents with social skills deficits. J Music Ther. (2011) 48:440–62. doi: 10.1093/jmt/48.4.440

51. Rickson D. Instructional and improvisational models of music therapy with adolescents who have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a comparison of the effects on motor impulsivity. J Music Ther. (2006) 43:39–62. doi: 10.1093/jmt/43.1.39

52. Rothmann K, Hillmer JM, Hosser D. [Evaluation of the Musical Concentration Training with Pepe (MusiKo mit Pepe) for children with attention deficits]. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. (2014) 42:325–35. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000308

53. Overy K. Dyslexia and music. From timing deficits to musical intervention. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2003) 999:497–505. doi: 10.1196/annals.1284.060

54. Habib M, Lardy C, Desiles T, Commeiras C, Chobert J, Besson M. Music and dyslexia: a new musical training method to improve reading and related disorders. Front Psychol. (2016) 7:26. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00026

55. Register D, Darrow AA, Standley J, Swedberg O. The use of music to enhance reading skills of second grade students and students with reading disabilities. J Music Ther. (2007) 44:23–37. doi: 10.1093/jmt/44.1.23

56. Flaugnacco E, Lopez L, Terribili C, Montico M, Zoia S, Schon D. Music training increases phonological awareness and reading skills in developmental dyslexia: a randomized control trial. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0138715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138715

57. Groß W, Linden U, Ostermann T. Effects of music therapy in the treatment of children with delayed speech development - results of a pilot study. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2010) 10:39. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-39

58. Mossler K, Schmid W, Assmus J, Fusar-Poli L, Gold C. Attunement in music therapy for young children with autism: revisiting qualities of relationship as mechanisms of change. J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 50:3921–34. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04448-w

Keywords: music therapy, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, neurodevelopmental disorder, systematic review

Citation: Mayer-Benarous H, Benarous X, Vonthron F and Cohen D (2021) Music Therapy for Children With Autistic Spectrum Disorder and/or Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 12:643234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643234

Received: 17 December 2020; Accepted: 11 March 2021;

Published: 09 April 2021.

Edited by:

Soumeyya Halayem, Tunis El Manar University, TunisiaReviewed by:

Omneya Ibrahim, Suez Canal University, EgyptCopyright © 2021 Mayer-Benarous, Benarous, Vonthron and Cohen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Cohen, ZGF2aWQuY29oZW5AYXBocC5mcg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.