94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Psychiatry, 05 March 2021

Sec. Psychopathology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.642322

Background: The psychopathological notion of the Praecox Feeling (PF) refers to an experience of strangeness and bizarreness that arises in a clinician during contact with a patient with schizophrenia. There is evidence that psychiatrists take advantage of this feeling in their diagnostic decisions despite the domination of an operationalized diagnostic approach.

Methods: The article presents the results of a survey assessing the self-reported prevalence of the PF among psychiatrists in Poland and compares them with data from West Germany (1962), USA (1989), and France (2017) based on the same survey.

Results: The study finds a consistent prevalence of reported feelings suggestive of the diagnosis of schizophrenia among psychiatrists of different cultural backgrounds and times. These feelings are independent of variables such as attitude toward schizophrenia, professional orientation, and professional experience and are considered reliable, even if not the most reliable, by the psychiatrists who have them. The study also finds that intersubjective phenomena, such as problematic affective attunement, gestures, and body language, are considered core to these feelings by the psychiatrists.

Conclusions: The evidence confirms that psychiatrists' feelings about patients with schizophrenia are considered diagnostically relevant and calls for more deeply investigating the nature and diagnostic significance of these feelings. The article concludes with some speculations regarding the possible benefits of recognizing the PF in facilitating a psychotherapeutic encounter with psychotic patients.

This article presents the results of a study investigating the prevalence of self-reports of the Praecox Feeling (PF) in diagnostic decision making among a population of psychiatrists in Poland. It compares these results cross-culturally (Germany, USA, France) and cross-historically (over 50 years). Finally, it discusses the possible implications of the findings for the structure of medical judgment in diagnosis and the potential implications of PF for the modeling of psychotherapies for psychosis.

Praecox Feeling (PF) is a highly ambiguous notion in the conceptual history of schizophrenia. It was first described by Rümke as an experience arising in the physician in contact with a person with schizophrenia. Rümke stated that it is remarkable that “it is rare for a clinician to be able to say exactly how he arrives at a diagnosis of schizophrenia” (1), the positive and negative symptoms being, in his view, non-specific. Instead, there is a specific atmosphere or hue of symptoms—an inability to come into contact with the other's personality as a whole—that induces an intuition that leads to diagnostic certainty (2). Elsewhere, Rümke describes PF as an unease in the relationship or foreclosure of empathy. PF has been considered an important determinant of medical decision making, with high diagnostic specificity referring implicitly to a specific gestalt of the schizophrenic experience (3). Other authors have argued that PF is part of an implicit perceptual process, also called “Typification” (4, 5), which allows us to grasp the singular mode of the self/world relationship. The theoretical issues of PF have been described elsewhere (6–8).

With the rise of operational diagnostic systems (ICD and DSM) and accusations of legitimizing arbitrary psychiatry, PF has fallen into disuse since the 1980s. This experiential dimension of the clinical approach has disappeared from medical teaching programs. It reappeared in scientific discussions in the last decade in the course of reflections on the validity of the clinical diagnostic approach to the spectrum of schizophrenia (9). In the absence of consistent biomarkers, the question of finding an adequate phenomenological marker for a rapid and precise diagnosis has arisen (10). Some scholars have argued that PF is a phenomenological marker of specific alteration of basic self-consciousness (11) and intersubjectivity (12–14). And since the basic sense of self may be a core phenotypic marker of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, it has been shown that acknowledging PF in a clinical examination can predict a deteriorating course of illness in populations with a high risk of psychosis (15, 16).

Very few empirical studies have produced evidence of PF's validity and reliability compared to the operational approach. Grube's study of 67 patients with acute positive psychotic symptoms measured the intensity of PF in an experienced clinician during a few minutes long interview. This intensity was compared to standardized diagnostic classifications assessed independently. The validity of PF was high (Sensibility = 0.88; Specificity = 0.82) (17). Ungvary et al. study of 102 patients (37 with schizophrenia) assessed the intensity of PF among five psychiatrists, which was then compared to the results of a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. This study showed very inconsistent results between the five evaluators and showed poor sensitivity and specificity (18).

Regarding the prevalence of PF use in clinical practice, a study based on a self-assessed questionnaire in Germany in the pre-DSM era (19) showed a significant prevalence of psychiatrists reporting their experiences as a reliable indicator of diagnosis (85.9%). A study was carried out with the same questionnaire in the USA in the DSM-III era (20) with a similarly high prevalence (82.9%). It was replicated recently in France in the DSM-5 era (21) with comparable results (90.1%). This suggests that psychiatrists continue to take advantage of their feelings for diagnostic decisions despite the apparent contradiction of this phenomenon with operational and criteriological methods.

We used a simplified version of Irle's original questionnaire from 1962 from West Germany (19); it was adapted by Sagi and Schwartz (20) in a survey conducted in New York, and re-adapted by us for a study in France in 2017 (9). We retained the key questions unchanged for cross-cultural and cross-historical comparison.

The key questions of interest concerned: (1) attitudes toward schizophrenia (options: essentially incurable, only improvable with remaining deficiencies, occasionally fully reversible); (2) the possibility of a rapid diagnosis by a skilled psychiatrist (yes/no); (3) self-reported feelings strongly suggestive of the diagnosis of schizophrenia (yes/no), which, following previous interpretations by Irle, Sagi, and Schwartz, and ourselves, were considered an indicator of PF. Those having the feelings in questions were asked to fill out part 2 of the survey concerning (4) the perceived reliability of these feelings (options: usually reliable, often wrong about them); and in case of usual reliability a further qualification (5) whether, despite occasional mistakes, they are more reliable than all other symptoms (options: yes/no); (6) whether they are expressible in words (yes/no); (7) whether they consider them a result of professional experience or an experience of “strangeness” that a layman would have as well. Finally, (8) we added an extra multiple-choice question on their perceived origin, with possible answers going back to Rümke's initial speculations as well as other possibilities (options: delusional or hallucinatory experience, problematic social cognition, problematic affective attunement, gestures and body language, gaze, other—please indicate).

The web-based multi-centric survey purposively targeted psychiatrists from major university clinics and psychiatric hospitals across Poland in late 2019/2020, located in Bialystok, Branice, Bydgoszcz, Cracow, Drewnica, Gdansk, Gniezno, Katowice, Koscian, Koszalin, Lodz, Lublin, Lubliniec, Miedzyrzecz, Olsztyn, Poznan, Plock, Pruszkow, Radom, Rybnik, Stronie Slaskie, Swiecie, Slupsk, Szczecin, Torun, Warsaw, Wroclaw. This was based on the assumption that clinicians working in major psychiatric clinics and hospitals more regularly deal with patients with schizophrenia. After reaching little <200 responses, the survey was circulated on a few psychiatrists' mailing lists. In order to avoid any negative or positive bias in psychiatrists familiar with the concept of PF, the invitation letter mentioned neither PF nor feelings suggestive of the diagnosis of schizophrenia—it merely asked for filling out a survey concerning the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Our Polish survey was filled out by 243 psychiatrists, 152 female and 91 male, both specialists and residents in training, with self-reported professional orientation varying from biological, through bio-psycho-social, to psychodynamic (see Table 1).

For statistical analysis, SPSS v.22 was employed. When assessing the interdependence of the variables, we used Pearson's χ2 test to measure whether the differences within the Polish samples and between the international samples are statistically relevant. Since variables were only nominal, we used Cramér's V (φc) test to measure the strength of associations between them.

As many as 89.3% (n = 217) of the sample of Polish psychiatrists occasionally experience feelings about a patient strongly suggestive of the diagnosis of schizophrenia. This is despite the fact that only 36.6% (N = 63) of the sample believe a skilled psychiatrist can diagnose schizophrenia very rapidly (i.e., within minutes of meeting the patient or even sooner). Furthermore, 77.4% (n = 161) of those having PF (n = 217) find it usually reliable. Females find it reliable more often (84.7%) than males (66.7%, p < 0.05), but the relationship with gender is not that strong (ϕc = 0.211). Only one-fourth of those who have PF (24.9%, n = 54) believe it is more reliable than all other symptoms (see Table 2).

The sample disclosed different attitudes toward schizophrenia, which is important given that historically PF advocates were rather Kraepelinian and believed that schizophrenia is degenerative (22, 23). Here, only 11.1% expressed the view that schizophrenia is essentially incurable, with 39.1% opting for occasionally reversible, and 49.8% for only improvable with remaining deficiencies. Interestingly however, these attitudes do not correlate with psychiatrists having or not having PF.

Also, psychiatrists' professional orientation (51.9% bio-psycho-social, 31.6% biological, 9.5% psychodynamic, 7% other) does not correlate with any of the abovementioned PF measures, except for the ability to express it in words. In the case of biological psychiatrists, it is significantly lower (36.8%) than in all the others (57.5%, p = 0.005, φc = 0.193).

Finally, psychiatrists report that the feelings in questions are due to problematic affective attunement (83.6%, n = 173), gestures and body language (58%, n = 120), problematic social cognition (56.5%, n = 117), and gaze (55.1%, n = 114), while only (38.6%, n = 80) ascribe it to delusional or hallucinatory experience (a multiple-choice question so values do not sum up to 100%). These answers correspond to Rümke's original exposition of the source of PF.

Our 2017 French study based on the same survey indicated that 90.1% of the sample declared feelings strongly suggestive of the diagnosis of schizophrenia—a result significantly higher than in previous West Germany (1962) and New York (1989) studies (p = 0.015). Seventy-four percent found it reliable—a significantly larger proportion (p = 0.009) than in previous studies, and 12.3% declared it more reliable than all other symptoms—a significantly lower proportion (p = 0.004) than in previous studies (21). Therefore, we speculated earlier about a possible French exception regarding the presence of PF and its reliability. However, the Polish study results are very close to the French one in terms of PF presence (89.3%) and to West Germany and New York ones in terms of PF being considered more reliable than all other symptoms (22.2%). The comparison of all four studies (see Table 3) shows significant differences regarding PF presence (p < 0.02), reliability (p < 0.001), and being the most reliable (p < 0.001), but Cramér's V (measuring the strength of associations between these variables) is very weak (V = 0.068, V = 0.17, V = 0.123, respectively).

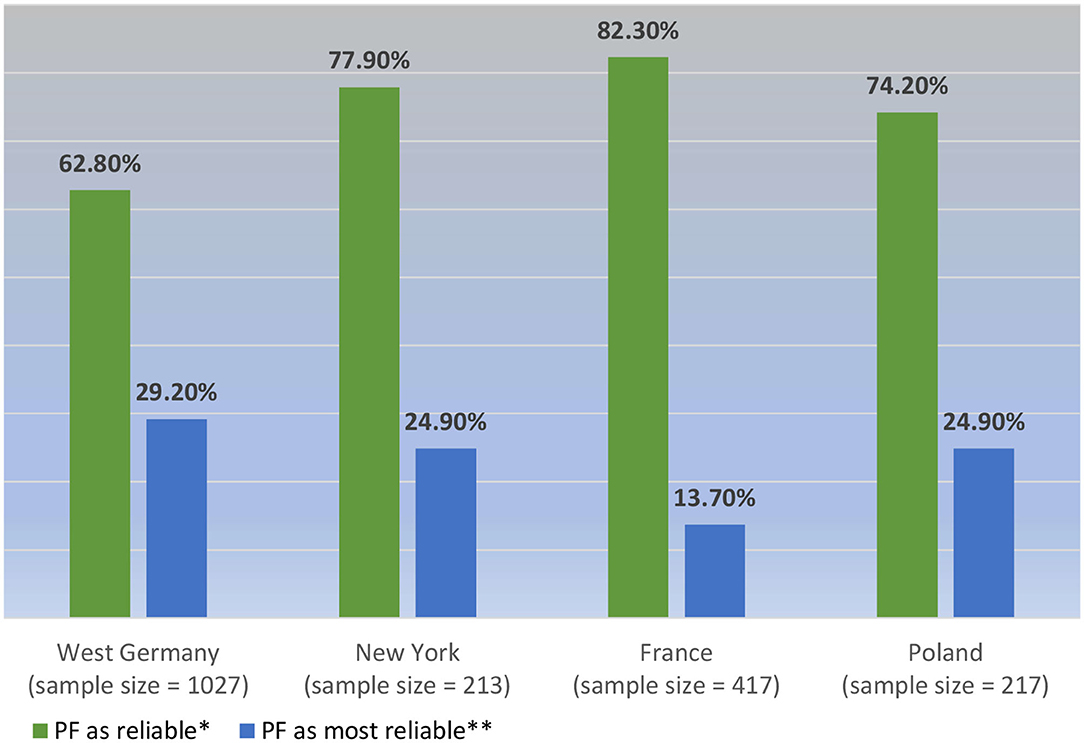

We may also combine those who report to experience PF in all four countries to construct a new artificial sample (n = 1874). With such a cross-cultural and cross-historical look, we find that 70.2% of all psychiatrists responding to the survey over the years considered the feelings in question reliable (n = 1315), but only 24.8% (n = 464) declared them more reliable than all other symptoms (see Figure 1). Given the low Cramér's V, the differences between the countries are equally negligible here.

Figure 1. PF considered reliability in a cross-cultural sample of psychiatrists who report it (N = 1,874). *p < 0.001; V = 0.184; **p < 0.001; V = 0.143.

In this light, we may conclude that there is a stable prevalence of feelings suggestive of the diagnosis of schizophrenia among psychiatrists of different cultural backgrounds and times, that the differences are negligible, and that the hypothesis of the French exception regarding PF presence (21) is unwarranted.

Our study indicates that PF is reported to be present in diagnostic decision-making and that is it considered reliable but not the most reliable indication by the psychiatrists themselves. For this reason, after a more thorough and experimental investigation, it could possibly guide diagnosis together with an operationalized approach. PF is also relatively independent of other variables and stable across the countries surveyed. The study also finds that what we interpret as intersubjective phenomena, such as problematic affective attunement, gestures, and body language, are considered at the core of PF by the psychiatrists who have it.

However, there are some limitations to these findings. For reasons explained above, the questionnaire's key question concerned feelings about a patient strongly suggestive of the diagnosis of schizophrenia and not PF explicitly. It is also important to underline that the considered reliability of PF is merely declarative, and it does not take into account the phenomenology of a singular encounter, in which it could be experimentally verified. In addition, even if the cross-cultural and cross-historical comparison is based on the same questionnaire, the studies compared were based on different types and sizes of samples. The German and the French studies used non-probability samples of the whole population of psychiatrists in West Germany and Marseille and Toulouse as well as residents from across France, respectively, but with high response rates of 51 and 25.6%. The New York study was a probability sample representative of New York County. In contrast, the Polish sample—which equaled the New York sample in size—was non-probability and mixed, and mainly targeted psychiatrists from major university clinics and psychiatric hospitals. In consequence, the international comparison conclusions cannot be representative of the psychiatrists' population.

We have speculated earlier following the New York study findings about the possible impact of expertise on PF, namely that the number of years spent in clinical practice would affect the belief in the rapid diagnosis and its reliability (7). In the Polish sample, however, the cut-off of 25 years of professional experience considered in the New York study does not bring any statistically significant differences regarding PF's presence, its perceived reliability, or any other tested variables. The only differences appear in the cut-off between residents in psychiatry and specialists. Specialists more often believe that the presence of PF is a result of their experience as psychiatrists and not just as an experience of strangeness that a layperson could have as well (80% of specialists against 64.3% of residents; p < 0.05, φc 0.175); and within the total sample of Polish survey respondents with PF (both specialists and residents, n = 217), 71.8% believe that this is due to their professional experience. At the same time, 84.2% of specialists against 71% of residents find PF reliable (p < 0.05, φc = 0.157), but given the low Cramér's V, the association is negligible. In conclusion, based on the new data from Poland, we cannot sustain the argument that professional expertise significantly affects PF. This implies that any psychiatrist—specialist or resident—could take advantage of their feeling suggestive of schizophrenia.

We may speculate that PF refers to a rupture in dynamic interactions between two embodied self-consciousness, physician's and patient's, which produces uncertainty of their dialogical synchrony. This break is noticed through the unease of the clinician, who finds the patient un-understandable, or bizarre, as Rümke already claimed (8). Disturbances in the interactive, phenomenal field are thus crucial. We hypothesized elsewhere, following Zahavi (24) among others, that PF presumably originates in the break of primordial connection between oneself, the other, and the world (7). This idea is close to that of Minkowski, who developed the so-called penetration diagnosis (25). This concept refers to the clinician's experience that the patient has “lost vital contact with reality.” This core determinant of the psychopathology of schizophrenia is based on Bergson's vitalist philosophy and refers to the “lived synchronism” of the person and the surrounding space. We may rethink this notion as the dynamic and embodied relationship of subjectivity with the outside world, including the other. Two currents nowadays support this line of thinking: on the one hand, phenomenologically inspired psychiatrists and philosophers, and, on the other, neuroscientific proponents of 4E cognition (Embodied, Embedded, Extended, and Enacted) (26) both at times overlapping to an extent. Both argue that the human mind is not just embodied but dialogical and that experience is relational in nature (27). Consequently, mental illness is not just in the brain; it is a complex, contextual and relational process (27–29). For the remainder of this paper, we shall briefly discuss the diagnostic and therapeutic relevance of this assumption.

Such conceptualization backed by the Polish data favors the idea that PF is a visible side of an alteration of intersubjectivity that every trained clinician could feel. To better understand how diagnostic decision-making is structured, it is useful to distinguish two PF levels. First, there is an atmospheric change and a feeling of strangeness of the encounter, difficult to describe because it is pre-reflective and non-declarative in nature, but one that a layman can sense. Referring to Gozé (8), we call this implicit level “bizarreness of contact.” And second, this experience can be refined by the professional training of a clinician who can cognitively recognize PF as a clinical sign and refer it to his/her clinical judgment. The reflexive level refers to what Rümke called PF—a phenomenon constructed in the context of diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic decisions. In the diagnostic process, the tacit (pre-reflective) and explicit (reflective) PF components work in a dialectical fashion and enrich each other. Thus, PF does not stand in opposition to evidence-based criteriological diagnosis (30). Indeed, if a clinician directs the medical interview in one direction rather than another, it is based, among other factors, on where PF directs them. This is why clinicians do not explore verbal acoustic hallucinations or delusions in all patients seen in consultation; PF directs them in one direction, sometimes without thinking about it. We believe that clinicians may learn to become attentive to and skillfully explore any breaks of intersubjectivity (28), and our study calls for integrating the ability to identify one's feelings into medical training. These phenomena may likely affect structured clinical interviews, and being alert to them may increase diagnostic accuracy.

The results of our cross-cultural and cross-historical comparison also call for experimental investigation of the therapeutic potential of PF. Would a greater openness of the clinician/therapist to PF-like experience and the ability to identify feelings and explore phenomenal intersubjective filed significantly affect the therapeutic process?

We may speculate that being attentive to PF could facilitate psychotherapeutic encounters with psychotic patients. PF could not be just a pre-reflective sign that facilitates more reflective diagnosis, but additionally an indicator of what should be dealt with during therapy in the first place. The self-reported presence of feelings that are strongly suggestive of schizophrenia may indicate that psychiatrists are capable of detecting subtle changes in affective attunement (83.6% of the Polish sample indicate problematic affective attunement as the supposed source of their feelings).

The aforementioned break in the phenomenal field and unease of the clinician, who finds the patient un-understandable, the feeling of isolation from the Other may be a resource for realizing the need for a response that would rebuild intersubjective relatedness. In the phenomenological and hermeneutic tradition of psychopathology, what should be explored is the phenomenal field of the encounter (28). Therapy should be experiential and embodied, immersed in the present, and focused on the process rather than on the content or the past (27, 28).

One possible example of a therapeutic approach relying on an embodied and relational understanding of the mind is the Open Dialogue—a systemic and dialogical method inspired by phenomenology (27, 28). From its perspective, the psychotic experience is largely an affective response to traumatic stress. Isolation and bizarre behavior result from the lack of an adequate response (27). Open Dialogue is a consistent implementation of humanistic and phenomenological ideas that may bring about better outcomes (27, 31, 32), although more research and evidence on efficacy is needed (33). Principles such as establishing a relationship with the Other without the intention to change the Other and tolerance of uncertainty are at the heart of this approach (34). Interpersonal relatedness developed therapeutically through unconditional response to all internal and external voices in the dialogue, including non-conceptual contact, allows the creation of a language to describe the experiences manifested in symptoms (31).

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

MM, MS, and TG conceived the study and prepared the survey. AB, MM, and PK collected the data. TG wrote the introduction. MM and PK wrote the methods and results section. AB, MM, and TG wrote the discussion. All authors contributed to the article, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the psychiatrists who helped to circulate and filled out the survey.

1. Rümke HC. Das kernsymptom der schizophrenie und das “praecox-gefühl.” Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr. (1941) 102:168–75.

3. Parnas J, Sass LA, Zahavi D. Rediscovering psychopathology: the epistemology and phenomenology of the psychiatric object. Schizophr Bull. (2013) 39:270–7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs153

4. Schwartz MA, Wiggins OP. Typifications: the first step for clinical diagnosis in psychiatry. J Nerv Ment Dis. (1987) 175:65–77. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198702000-00001

5. Fernandez AV. “Phenomenology, typification, and ideal types in psychiatric diagnosis and classification,” In: Bluhm R, editor. Knowing and Acting in Medicine. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield International (2016). p. 39–58.

6. Pallagrosi M, Fonzi L. On the concept of praecox feeling. Psychopathology. (2018) 51:353–61. doi: 10.1159/000494088

7. Moskalewicz M, Schwartz MA, Gozé T. Phenomenology of intuitive judgment: praecox-feeling in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. AVANT. (2018) 9:63–74. doi: 10.26913/avant.2018.02.04

9. Gozé T, Moskalewicz M, Schwartz MA, Naudin J, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Cermolacce M. Reassessing “praecox feeling” in diagnostic decision making in schizophrenia: a critical review. Schizophr Bull. (2019) 45:966–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby172

10. Stanghellini G, Rossi R. Pheno-phenotypes: a holistic approach to the psychopathology of schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2014) 27:236–41. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000059

11. Parnas J. A disappearing heritage: the clinical core of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2011) 37:1121–30. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr081

12. Fuchs T. Subjectivity and intersubjectivity in psychiatric diagnosis. Psychopathology. (2010) 43:268–74. doi: 10.1159/000315126

13. Varga S. Vulnerability to psychosis, I-thou intersubjectivity and the praecox-feeling. Phenom Cogn Sci. (2013) 12:131–43. doi: 10.1007/s11097-010-9173-z

14. Pallagrosi M, Fonzi L, Picardi A, Biondi M. Assessing clinician's subjective experience during the interaction with patients. Psychopathology. (2014) 47:111–8. doi: 10.1159/000351589

15. Nelson B, Yung AR. Can clinicians predict psychosis in an ultra high risk group? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2010) 44:625–30. doi: 10.3109/00048671003620210

16. Nelson B, Thompson A, Yung AR. Basic self-disturbance predicts psychosis onset in the ultra high risk for psychosis “prodromal” population. Schizophr Bull. (2012) 38:1277–87. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs007

17. Grube M. Towards an empirically based validation of intuitive diagnostic: Rümke's “praecox feeling” across the schizophrenia spectrum: preliminary results. Psychopathology. (2006) 39:209–17. doi: 10.1159/000093921

18. Ungvari GS, Xiang Y-T, Hong Y, Leung HCM, Chiu HFK. Diagnosis of schizophrenia: reliability of an operationalized approach to “praecox-feeling”. Psychopathology. (2010) 43:292–9. doi: 10.1159/000318813

19. Irle G. Das “praecoxgefuehl” in der diagnostik der schizophrenie. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr. (1962) 203:385–406.

20. Sagi GA, Schwartz MA. The “praecox feeling” in the diagnosis of schizophrenia; a survey of Manhattan psychiatrists. Schizophr Res. (1989) 2:35. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(89)90071-6

21. Gozé T, Moskalewicz M, Schwartz MA, Naudin J, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Cermolacce M. Is “praecox feeling” a phenomenological fossil? A preliminary study on diagnostic decision making in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2019) 204:413–4. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.07.041

22. Rümke HC. La difference clinique à l'intérieur du groupe des schizophrénie. L'Evol Psychiatr. (1958) 3:525–38.

23. Neelman J. The legacy of Dutch psychiatry. Psychiatr Bull. (1990) 14:222–3. doi: 10.1192/pb.14.4.222

24. Zahavi D. Beyond empathy: phenomenological approaches to intersubjectivity. J Conscious Stud. (2001) 8:151–67. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0036

26. Newen A, De Bruin L, Gallagher S. The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2018).

27. Seikkula J. Psychosis is not illness but a survival strategy in severe stress: a proposal for an addition to a phenomenological point of view. Psychopathology. (2019) 52:143–50. doi: 10.1159/000500162

28. Fuchs T. The interactive phenomenal field and the life space: a sketch of an ecological concept of psychotherapy. Psychopathology. (2019) 52:67–74. doi: 10.1159/000502098

29. Fuchs T, Röhricht F. Schizophrenia and intersubjectivity. An embodied and enactive approach to psychopathology and psychotherapy. Philos Psychiatry Psychol. (2017) 24:127–42. doi: 10.1353/ppp.2017.0018

30. Jansson L, Nordgaard J. The Psychiatric Interview for Differential Diagnosis. New York, NY: Springer (2016).

31. Seikkula J, Arnkil TE. Open Dialogues and Anticipations: - Respecting Otherness in the Present Moment. Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare (2014).

32. Seikkula J. “From research on dialogical practice to dialogical research: open dialogue is based on a continuous scientific analysis,” In: Ochs M, Borcsa M, Schweitzer J, editors. Systemic Research in Individual, Couple, and Family Therapy and Counseling. European Family Therapy Association Series. Cham: Springer (2020). p. 143–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36560-8_9

33. Freeman AM, Tribe RH, Stott JCH, Pilling S. Open dialogue: a review of the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. (2019) 70:46–59. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800236

34. Olson M, Seikkula J, Ziedonis D. The Key Elements of Dialogic Practice in Open Dialogue. Worcester, MA: The University of Massachusetts Medical School (2014). Available online at: https://medschool.ucsd.edu/Pages/results.aspx#stq=open%20dialogue

Keywords: schizophrenia, praecox feeling, diagnosis, psychopathology, phenomenology, bizarreness, expertise

Citation: Moskalewicz M, Kordel P, Brejwo A, Schwartz MA and Gozé T (2021) Psychiatrists Report Praecox Feeling and Find It Reliable. A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Front. Psychiatry 12:642322. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.642322

Received: 15 December 2020; Accepted: 11 February 2021;

Published: 05 March 2021.

Edited by:

Roumen Kirov, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, BulgariaReviewed by:

Neil Dagnall, Manchester Metropolitan University, United KingdomCopyright © 2021 Moskalewicz, Kordel, Brejwo, Schwartz and Gozé. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcin Moskalewicz, bW9za2FsZXdpY3pAZ21haWwuY29t orcid.org/0000-0002-4270-7026

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.