94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Psychiatry, 12 February 2021

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.638874

This article is part of the Research TopicDeath and Mourning Processes in the Times of the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)View all 47 articles

Although death is an inherent part of life, for many it is a terrifying event, which awareness is often to be avoided at all costs (1). However, with the daily updates of COVID-19 cases and deaths, the confrontation with human mortality and physical fragility is unavoidable. Over 100 million confirmed cases and over 2 million confirmed deaths worldwide have been recorded (2). The COVID-19 pandemic is a health crisis unprecedented in contemporary history.

Furthermore, an estimate of 9 bereaved family members results from each COVID-19 death (3). Recent evidence indicates that, due to the circumstances in which deaths in the COVID era occur—unexpected and shocking deaths, social distancing, restrictions in visits in healthcare facilities and in funerals—another epidemic is on the rise: prolonged grief disorder (PGD) [e.g., (4)]. PGD is characterized by persistent and pervasive longing for, or preoccupation with the lost one, as well as severe emotional pain (such as, guilt, anger, or sadness), difficulty accepting the death, emotional numbness, a sense that a part of them has been lost, an inability to experience positive mood and difficulty participating in social activities (International Classification of Diseases-11, (5)).

With each death that occurs, there are loved ones who will be deeply impacted by the loss, particularly at a time when, due to sanitary restrictions, they may experience limited autonomy, and resourcefulness when coping with their grief. The awareness of these limitations heighten the risk of grievers experiencing their grief as disenfranchised to a degree.

Kenneth Doka first formally introduced the notion of disenfranchised grief in 1989 and defined it as the process in which the loss is felt as not being “openly acknowledged, socially validated, or publicly mourned” (1989, p. xv). This experience of grief might pose difficulties in terms of emotional processing and expression, as one may not recognize his/her right to grieve, and in terms of social support, by diminishing the opportunity to freely express their emotions, and to obtain expressions of compassion and support (6).

Given the challenges that the disenfranchisement of grief might add to the bereavement experience, it is important to reflect on the risk for this experience in the context of the COVID-19 circumstances. In this opinion paper we aim to frame this in light of the felt limitations in autonomy and resourcefulness in the COVID-19 bereaved, either imposed externally, or internally (self-disenfranchisement).

Doka (6) suggests that which losses and which relationships have the legitimacy of being grieved is defined by each society's grieving norms. When a loss does not accommodate these guidelines, the resultant grief remains unrecognized and undervalued and a person may feel as his/her “right to grieve” has been denied. So it seems that there are bereavements that are not socially acceptable, in which its grieving is complex and triggers secondary variables like the disenfranchised grief. According to Corr (7) an aspect that contributes to the grieving process being disenfranchised is the devaluing of public mourning rituals. Arguably, restrictions are needed to contain the spread; however, there are concerns about how current restrictions in end of life care and funeral rites may compromise the salutary grieving process and amplify the risk for disenfranchised grief.

The usual rituals, customs and interactions that occur in the context of end of life and after a death are another casualty of the virus. During end of life, in order to conform with the guidelines for preventing the spread of the disease, patients are often faced with separation from their loved ones reporting high levels of loneliness, uncertainty and despair. In the same way, it could increase feelings of neglect and dehumanized treatment (8).

In addition, Bromberg (9) identifies therapeutic functions in the funeral rituals: (1) they assist family members and friends in recognizing and confronting the reality of the loss; (2) they offer room for introspection on the death as a process integrated into life; (3) they foster the awareness and assimilation of the grief process. These therapeutic functions may be deeply compromised currently as families are deprived from access to social support and usual burial and funeral rituals.

Funeral rituals have been taking place with a reduced number of family members present, leaving the online mode as the only option for many people. These virtual interactions don't replace usual in person interactions and rituals. Not only did they previously include both immediate and extended family members and friends but allowed for physical connection and touch—a pat in the back, a stroke, a hug (10). Sharing their pain with other bereaved people, and having a place of memorialization, may foster emotion expression and meaning-making for bereaved people (11, 12). Therefore, bereaved people may find the shortage or minimalistic nature of funerary rituals painful (13). Also challenging is the perception that their loved one didn't receive the funerary ritual they deserved, not being able to say farewell to the deceased and not being able to visit the grave afterwards (14).

Likewise, feeling disallowed and unsupported to openly express and manage their grief may contribute to disenfranchisement (15). We are facing times that compromise the normal and necessary social support usually available during the illness and after death. Touch is a basic human need, especially in grief, and can help the person in their coping process after a loss (16). It could help to ground in the present moment (here and now), to have someone, something to hold on to.

Finally, the increasing accumulation of deaths could impede acknowledgment of each individual's grief. The deaths framed as statistic also leaves the bereaved individuals feeling that the pain of their loss in undervalued. In addition, not only can grief be overlooked by society but patients and their families can also experience social stigma regarding COVID-19 losses (17).

Expanding on Doka's original work on disenfranchised grief, Kauffman (18) proposed the concept of self-disenfranchisement, which occurs when individuals have difficulty in acknowledging their own grief as being legitimate. One proposed associated emotion of these situations is guilt, which is especially present in situations of unexpected or sudden loss (19). In the present pandemic context, bereaved people have scarce opportunities to prepare for their loss as, after contracting the virus, it can only take weeks or even days for the person to die. Literature has shown that sudden deaths in the context of intensive care are associated with more mental health problems (20), and highlight the particular impact of the lack of information and the consequent intrusive constant doubts (21). Examples of these doubts in the present context may refer to whether the person has suffered or if they have received appropriate care (associated with the perception of resource scarcity). They may also wonder why they were spared and whether they had a part in the person getting infected (8). Also, the bereaved may feel guilty for not being able to be present at the time of death; for not having reaffirmed their love, providing comfort as they wished to or saying goodbye (22). An experience of guilt-shame at their impotence may therefore be magnified in the current pandemic context (23).

On the other hand, self-disenfranchisement may be related to not having the emotional safeness conditions and coping resources in order to fully connect with their pain and grieving process. One aspect that may contribute to this is the current rise in pandemic-related anxiety and depression levels. It may deplete the emotional resources needed to grieve the loss of the person, on its own, or due to the risk of triggering previous mental illness issues (24). Also, the overload concept of the well-established Dual Process Model (25) may be particularly representative of the current grieving context. These authors argue that apart from the necessary oscillation between loss-oriented coping (confronting and handling feelings of grief and loss) and restoration-oriented coping (stressors of daily life that result from the death) it is important to evaluate the existence of more loss or restoration stressors than the person feels capable of handling. It is our view that the COVID-19 pandemic poses serious risks of overload of restoration stressors. First of all, simultaneously to the already arduous process of grieving, individuals are experiencing varying degrees of personal, economic and social losses (26). Also, as people are being deprived of usual social, recreational, and occupational activities, there are less opportunities for taking time off from the overwhelming emotional experience of grief. Likewise, without face-to-face meetings, after-death practicalities (e.g., sort out phone contracts in the deceased person's name, bank accounts, liaise with funeral directors) may be more difficult to some, especially those with less technology resources, paving the way to difficulties in accepting the loss. Finally, access to support services and social support is much harder. In general, overall needs for grieving and bereavement are largely unattended.

Despite acknowledging the importance of future research investing at primary empirical data, in this opinion paper we aimed at offering a preliminary and exploratory view of the risk for disenfranchisement in grief and bereavement in the current pandemic context.

Therefore, in this context, access to evidence-based bereavement psychological interventions is critical. The existing gaps in the area of mental health can contribute to the lack of investment among the bereaved. Therefore, in order to better prepare for managing grief-related mental health issues, we must first increase general public's literacy around mental health and grief (grief-informed communities), combating stigma and discrimination (27).

For this purpose, we need a public health approach aimed at restoring the normal social and community support systems. It is also important to be aware of risk factors in order to intervene earlier and effectively in the mental health issues and in the grief process. Simultaneously, it could be relevant to build intervention protocols that involve screening and mental health risk assessment for those with greater risk factors for grief complexities.

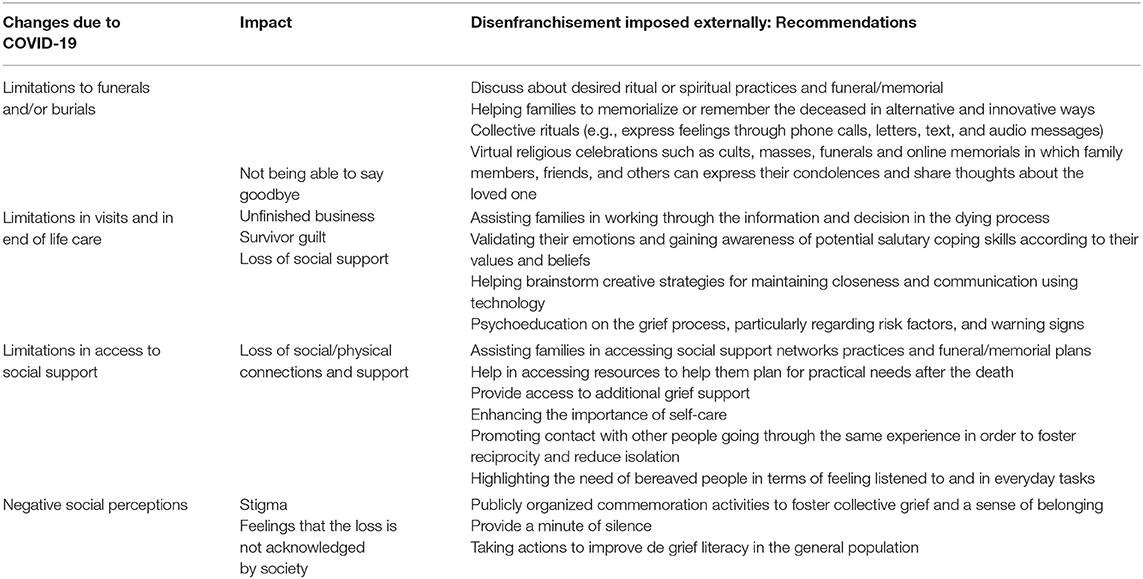

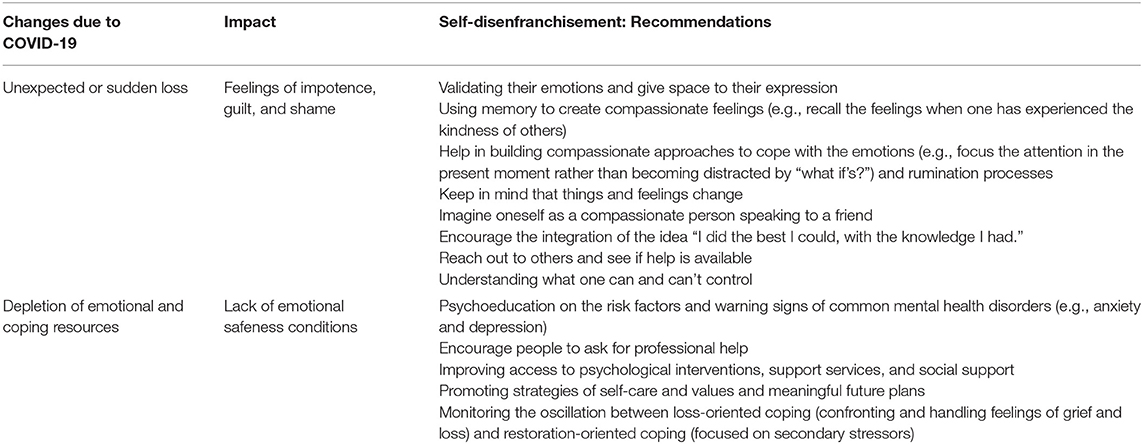

In addition, specific recommendations regarding coping with social restrictions in funerals, access to social support, and in regards to promoting more supportive social perceptions for bereaved people are offered in Table 1. Recommendations to address feelings of impotence, guilt and shame and lack of emotional and coping resources are offered in Table 2.

Table 1. Recommendations regarding disenfranchisement imposed externally to promote healthy COVID-19 related grieving.

Table 2. Recommendations regarding self-disenfranchisement to promote healthy COVID-19 related grieving.

COVID-19 related deaths are in multiple ways lonely and dehumanized processes for patients and families. Limitations in self-efficacy, choice, and control not only changed the landscape of grief and grieving but pose a significant risk and added burden in the already arduous and painful grieving experience.

SA and AT contributed to the development of the idea, the literature research, and the writing of the manuscript. JR provided critical feedback.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Solomon S, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T. The cultural animal: twenty years of terror management theory and research. In: Greenberg J, Koole SL, Pyszczynski T, editors. Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2004). p. 13–34. doi: 10.1037/e631532007-001

2. World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

3. Verdery AM, Smith-Greenaway E, Margolis R, Daw J. Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proce Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:17695–701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007476117

4. Eisma MC, Boelen PA, Lenferink L. Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:113031. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113031

5. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (11th Revision). Geneva: World Health Organization (2018). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

6. Doka KJ. (Ed.). Disenfranchised Grief: New Directions, Challenges, and Strategies for Practice. Champaign, IL: Research Press (2002).

7. Corr CA. Revisiting the concept of disenfranchised grief. In: Doka KJ, editor. Disenfranchised Grief: New Directions, Challenges, and Strategies for Practice. Champaign, IL: Research Press (2002). p. 39–60.

8. Taylor S. The Psychology of Pandemics: Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak of Infectious Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2019).

9. Bromberg MHP. A Psicoterapia em Situações de Perdas e Luto. São Paulo: Editora Livro Pleno (2000).

10. Fang C, Comery A. Understanding grief in a time of COVID-19 - a hypothetical approach to challenges and support. J Popul Ageing. (2020). doi: 10.31124/advance.12687788.v1. [Epub ahead of print].

11. Davies D. Death, Ritual and Belief: The Rhetoric of Funerary Rites. London: Bloomsbury Publishing (2017).

12. Walter T. A new model of grief: Bereavement and biography. Mortality. (1996) 1:7–25. doi: 10.1080/713685822

13. O'Rourke T, Spitzberg BH, Hannawa AF. The good funeral: toward an understanding of funeral participation and satisfaction. Death Stud. (2011) 35:729–50. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2011.553309

14. Ingravallo F. Death in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Pub Health. (2020) 5:e258. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30079-7

15. Doka KJ. Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Hidden Sorrow. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books (1989).

16. Johns L, Blackburn P, McAuliffe D. COVID-19, Prolonged Grief Disorder and the role of social work. Int Soc Work. (2020) 63:660–4. doi: 10.1177/0020872820941032

17. Kokou-Kpolou CK, Cénat JM, Noorishad PG, Park S, Bacqué MF. A comparison of prevalence and risk factor profiles of prolonged grief disorder among French and Togolese bereaved adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2020) 55:757–64. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01840-w

18. Kauffman J. The psychology of disenfranchised grief: Liberation, shame, and self-disenfranchisement. In: Doka K, editor. Disenfranchised Grief: New Directions, Challenges, and Strategies for Practice. Champaign, IL: Research Press (2002). p. 61–77.

19. Holst-Warhaft G. The Cue for Passion: Grief and Its Political Uses. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (2000). doi: 10.4159/harvard.9780674498587

20. Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, Loseth DB, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. (2008) 36:1722–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72

21. Van der Klink MA, Heijboer L, Hofhuis JGM, Hovingh A, Rommes JH, Westerman MJ, et al. Survey into bereavement of family members of patients who died in the intensive care unit. Intens Crit Care Nurs. (2010) 26:215–25. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2010.05.004

22. Van Bortel T, Basnayake A, Wurie F, Jambai M, Koroma AS, Muana AT, et al. Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community and international levels. Bull World Health Organ. (2016) 94:210–4. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.158543

23. Tay AK, Rees S, Steel Z, Liddell B, Nickerson A, Tam N, et al. The role of grief symptoms and a sense of injustice in the pathways to post-traumatic stress symptoms in post-conflict timor-leste. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2017) 26:403–13. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000317

24. Xiang Y-T, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:228–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8

25. Stroebe M, Schut H. Overload: A Missing Link in the Dual Process Model? OMEGA J Death Dying. (2016) 74:96–109. doi: 10.1177/0030222816666540

26. Mayland CR, Harding AJE, Preston N, Payne S. Supporting adults bereaved through COVID-19: a rapid review of the impact of previous pandemics on grief and bereavement. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2020) 60:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.012

Keywords: death, grief, bereavement, disenfranchised grief, COVID-19

Citation: Albuquerque S, Teixeira AM and Rocha JC (2021) COVID-19 and Disenfranchised Grief. Front. Psychiatry 12:638874. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.638874

Received: 07 December 2020; Accepted: 22 January 2021;

Published: 12 February 2021.

Edited by:

Lydia Gimenez-Llort, Autonomous University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

María Nieves Pérez-Marfil, University of Granada, SpainCopyright © 2021 Albuquerque, Teixeira and Rocha. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sara Albuquerque, c2FyYW1hZ2FsaGFlczlAbXNuLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.