94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Psychiatry , 28 April 2021

Sec. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.630029

This article is part of the Research Topic Advances in Social Cognition Assessment and Intervention in Autism Spectrum Disorder View all 22 articles

Marine Dubreucq1,2*

Marine Dubreucq1,2* Julien Dubreucq1,2,3,4

Julien Dubreucq1,2,3,4Later age of diagnosis, better expressive behaviors, increased use of camouflage strategies but also increased psychiatric symptoms, more unmet needs, and a general lower quality of life are characteristics often associated with female gender in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Psychiatric rehabilitation has shown small to moderate effectiveness in improving patients' outcomes in ASD. Few gender differences have been found in the response to psychiatric rehabilitation. This might be related to the predominance of males in research samples, but also to the lack of programs directly addressing women's unmet needs. The objectives of the present paper were: (i) to review the needs for care of autistic women in romantic relationships and reproductive health; (ii) to review the existing psychosocial treatments in these domains; and (iii) to evaluate the strengths and limitations of the current body of evidence to guide future research. A systematic electronic database search (PubMed and PsycINFO), following PRISMA guidelines, was conducted on autistic women's needs for care relating to psychiatric rehabilitation in romantic relationships and reproductive health. Out of 27 articles, 22 reported on romantic relationships and 16 used a quantitative design. Most studies were cross-sectional (n = 21) and conducted in North America or Europe. Eight studies reported on interventions addressing romantic relationships; no published study reported on interventions on reproductive health or parenting. Most interventions did not include gender-sensitive content (i.e., gender variance and gender-related social norms, roles, and expectations). Autistic women and autistic gender-diverse individuals may face unique challenges in the domains of romantic relationships and reproductive health (high levels of stigma, high risk of sexual abuse, increased psychiatric symptoms, and more unmet needs). We discussed the potential implications for improving women's access to psychiatric and psychosocial treatment, for designing gender-sensitive recovery-oriented interventions, and for future research.

Increasing research interest on potential sex/gender differences in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has led to the description of a “female phenotype” of ASD characterized by similarities in core ASD symptoms (i.e., lifelong social impairment, communication deficits, and repetitive behavior), better expressive behaviors (e.g., sharing interests or more vivid gestures), increased use of camouflage strategies, later age of diagnosis, but also higher increased depression and anxiety, and a general lower quality of life (1). In the present study, we used the term sex to refer to biological characteristics and the term gender to refer to sociocultural norms, roles, expressions, and expectations (2). Given the high frequency of gender variance (i.e., gender identity or gender expression that does not conform to masculine or feminine gender norms) (3) in ASD, we used self-reported gender identity (i.e., cisgender women, but also transgender or non-binary women) to define female gender in this study (4).

Psychiatric rehabilitation is a person-centered approach that aims to help people with serious mental illness (SMI) or ASD to “be successful and satisfied in the living, working, learning, and social environments of their choice” (5). Therapeutic tools are selected based on people's strengths, weaknesses, needs for care, and personal life goals as part of a customized recovery-oriented action plan (6, 7). The action plan can include strength-based case management, improvements in physical and mental health, peer support interventions, joint crisis plans, cognitive remediation (CR), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), social skills training (SST), self-stigma reduction, family support, and supported housing and supported employment (SE) (6, 7). Psychiatric rehabilitation interventions have shown small to moderate effectiveness in improving patients'outcomes in adults with ASD (8–11).

Although no gender differences were found in social participation and the employment rates, women were less likely than men to have long-standing friendships and to maintain post-secondary/employment over time (12–14). To date, three studies have looked for potential gender differences in the response to psychosocial treatment in adults with ASD (15, 16). McVey et al. (15) and Visser et al. (17) found no gender differences in treatment outcomes for SST, whereas Sung et al. (16) reported that men benefited more from vocational rehabilitation.

The predominance of males in research samples may induce gender-related biases affecting the development of psychosocial interventions (18). Two recent systematic reviews have reported a large predominance of males in studies on cognitive remediation or social skills training [up to 100% in some studies (8, 19)]. Similar proportions have been reported in studies targeting social skills in dating contexts (20, 21). Autistic women report more unmet needs with respect to their mental health concerns and vocational services (21, 22) and report a higher risk of sexual abuse (×2.2) (23, 24). Gender variance has been associated with higher depression and reduced well-being in autistic women (25). It could be associated with the higher risk of sexual abuse (25). Reproductive and parenting issues, which may be more salient in women with ASD than in men, remain underinvestigated (26, 27).

The objectives of the present paper were: (i) to review the needs for care of autistic women in romantic relationships and reproductive health; (ii) to review the existing psychosocial treatments in these domains; and (iii) to evaluate the strengths and limitations of the current body of evidence to guide future research.

A stepwise systematic literature review (PRISMA guidelines) (28) was conducted by searching PubMed, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO for published peer-reviewed papers using the following keywords: “sexu*” OR “romantic relationship” OR “intimate relationship” OR “parent*” OR “reproductive health” OR “mother*” OR “pregn*” AND “women” OR “gender diverse” OR “transgender” OR “non-binary” AND “autism” NOT “valproate” NOT “22q11.” No time restriction was set. Only published papers in English or French were included in the review. The reference list of seven literature reviews on sexuality and autism were screened for additional relevant articles. To be included in this review, the articles had to meet all of the following criteria: (a) have a main focus on women's outcomes; (b) concern a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder; (c) report on romantic relationships or parenting; and (d) use a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods design. The first author applied the eligibility criteria and screened the records to select the included studies. The last author reviewed each decision. Disputed items were solved through discussion and by reading the paper in detail to reach a final decision. For each study, we extracted the following information: general information (author, year of publication, country, design, population considered, setting, total number of participants, and mean age or age range), outcome measure (scale), the main findings, and the variables relating to quality assessment. Quality assessment was performed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (29). This tool comprises five sets of criteria for: (a) qualitative, (b) randomized controlled trials, (c) non-randomized trials, (d) descriptive studies, and (e) mixed-methods studies. For the mixed-methods studies, raters assess the qualitative set, the quantitative set, and the mixed-methods set. An overall quality score (low, moderate, high, or very high) was determined based on adequacy in the corresponding set of criteria.

Our search on January 13, 2021 found 672 articles on PubMed and 187 on PsycINFO. After manually removing all duplicates, there were 450 remaining references. Based on their titles and abstracts, 404 papers were excluded for lack of relevance. Most of these articles focused on other populations (e.g., parents of children or adolescents with autism, healthcare professionals, other neurodevelopmental conditions, and autistic traits in the general public) or other topics (e.g., biological sex differences, physical health, and vocational function). Our search strategy yielded 46 full-text articles. After conducting a full-text analysis of all these papers and excluding those that did not meet the inclusion criteria, we ended up with 27 relevant papers (Figure 1).

The 27 papers included were characterized by the heterogeneity of their samples, methods, and reported outcomes. Most papers reported on romantic relationships (n = 22, 81.4%) and used a quantitative design (n = 16, 59.3%). Ten studies were qualitative and one was mixed methods. Most studies used cross-sectional designs (n = 21, 77.8%). Six studies reported on interventions (22.2%). Two studies were a randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and four studies used quasi-experimental or non-controlled designs. Eleven studies were conducted in North America (40.8%), nine in Europe (33.3%), and seven in Australia (25.9%). Most studies included adult participants (n = 22, 81.5%). One study included only adolescents (3.7%) and two studies had mixed samples (7.4%). Three studies (11.1%) included both parents and ASD participants. Of the studies using a quantitative or a mixed-methods design, most reported on sexuality-related outcomes (e.g., sexual desire, sexual awareness, sexual well-being, and sexual assertiveness; n = 10, 62.5%). One study reported on social skills in the context of dating (21) and one on general social skills (30). Two quantitative studies used self-reported assessments for parenting-related outcomes (27, 31). The quality ratings of the included studies obtained using MMAT ranged from low to moderate. The results are shown in Table 1.

Loneliness, negative self-perceptions, self-stigma, sensory sensitivity, and impaired social communication related to dating situations have been identified as barriers to romantic relationships in ASD (33). Women with ASD may face unique challenges in their adolescence and during the transition to adulthood, such as decrypting dating situations (e.g., judging subtle social cues in dating situations such as flirting, aggression, or coercion) and adopting assertive behaviors in intimate relationships (34). Compared with non-autistic women, autistic women have less sexual interest, but had more experiences and received more unwanted sexual advances (24, 35, 36). They report lower sexual well-being and have an increased risk of sexual abuse (24, 34, 37). Engagement in sexual behaviors to reduce social exclusion and alcohol use to reduce social anxiety could increase the risk of victimization in women with ASD (24, 32, 34).

This risk might be higher for non-binary or transgender autistic women who may also face unique challenges in romantic relationships (e.g., relating to the intersection of ASD and the gender identity stigma) (25, 33, 38). Bargiela et al. (34) and Kanfiszer et al. (32) reported that, after being diagnosed with ASD, autistic women needed to reframe past negative experiences and to discuss gender-related social roles and expectations. Compared with typically developing women and autistic men, autistic women expressed less desire to live with a partner (32, 39, 40). Those living with a typically developing partner reported social and communications challenges, but also to have resources to deal with them (41). Marital satisfaction was higher for autistic women living with an autistic partner (40). Support from healthcare and social professionals was often described as inadequate (41). Table 2 presents the characteristics of the included studies on romantic relationships.

Four interventions addressed romantic relationships in women with ASD. One was a general SST program including social skills in dating (Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relationship Skills, PEERS) (15) and the other a social skills in dating program (Ready for Love) (21). Two programs were psychosexual trainings for autistic adolescents [socio-sexual training (43) and Tackling Teenage (17)]. Participants in these interventions were mostly male (>75%) (15, 17, 21). McVey et al. (15) and Visser et al. (17) reported no gender differences in treatment effects for PEERS and Tackling Teenage. One SST intervention was designed for autistic female adolescents (the Girls Night Out model) (30), but did not address dating or romantic relationships. Two qualitative studies assessed stakeholders' needs to design new interventions (38, 44). Common factors to these interventions were the emphasis put on: (i) group-based interventions to receive support from other participants; (ii) peer support; (iii) discussions about gender variance and gender-related social roles and expectations; iv) improving social cognition and social skills; and v) interventions supporting the relatives (38, 43, 44). Descriptions of the interventions are shown on Table 3.

To date, a few qualitative studies and two quantitative studies have investigated the experiences of motherhood in ASD. Kanfiszer et al. (32) reported that some autistic women identified motherhood as a potential trigger of stress more than a rewarding experience and reported to have “no maternal instinct.” In a sample comparing the experiences of 355 mothers with ASD with those of 132 non-autistic mothers, Pohl et al. (27) have found that autistic mothers had an increased frequency of perinatal depression. Although most autistic mothers described parenting as a rewarding experience, they were more prone than non-autistic mothers to find it also challenging and isolating (27). Autistic mothers were more likely to report parenting difficulties (e.g., with household responsibilities or with the multitasking demands of parenting) and to be dissatisfied with service provision during perinatal care (e.g., feeling judged in their parenting abilities) (27, 46, 47). They described stressful and negative experiences in communicating with healthcare professionals and social workers about their child (27, 46, 47). Some women reported to have concealed their diagnosis to providers to avoid stigmatizing behaviors and child protective services implications (46, 47). Other factors associated with negative experiences in perinatal care included uncertain and stressful environment and sensory sensitivity (46–48). Sundelin et al. (31) have reported that, compared to children of non-autistic mothers, those of autistic mothers had poorer obstetrical and neonatal outcomes (e.g., pre-term birth, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery). Table 4 shows the characteristics of the included studies on parenting.

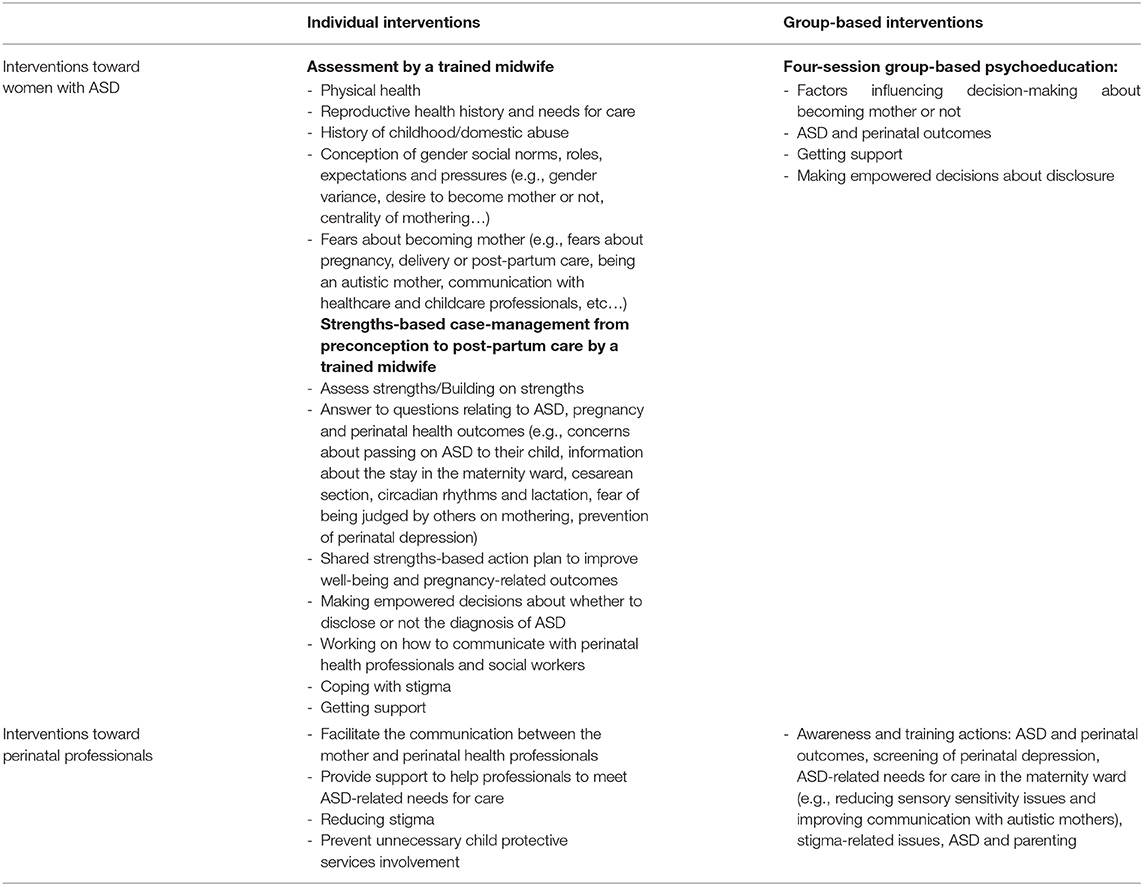

According to Pohl et al. (27), autistic mothers were dissatisfied of the support they received during perinatal care and felt that they should be offered extra support because of their autism. Gardner et al. (46), Rogers et al. (47), and Pohl et al. (27) reported a need for clear and accurate information about normal pregnancy, potential complications, delivery, and post-partum care. To our knowledge, no published studies described interventions to improve reproductive health outcomes and to support parenting in autistic mothers. In the FondaMental Advanced Center of Expertise for ASD (FACE-ASD) of Grenoble, consultation with a trained midwife has been added to the diagnosis and functional assessment. The objectives were: (i) to assess the desire to become a parent; (ii) to answer questions relating to ASD, pregnancy, and perinatal health outcomes (e.g., concerns about passing on ASD to their child, information about the stay in the maternity ward, cesarean section, circadian rhythms, and lactation); (iii) to propose strengths-based case management and a shared recovery-oriented action plan to improve well-being and pregnancy-related outcomes; (iv) to provide individual and/or family psychoeducation; and (v) to improve the communication with perinatal health professionals and social workers. Actions addressing mothers and their partners' needs or aiming to improve knowledge of perinatal health professionals about ASD and to reduce ASD-related stigma could be provided during the perinatal period (i.e., from preconception to 1 year after childbirth). A group-based program on reproductive health and parenting issues for women with ASD and their partners was also developed. It includes three 2-h sessions during which participants and facilitators discuss issues related to reproductive health and parenting (e.g., concerns about heredity or communication with healthcare professionals). A detailed description of these actions is presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Example of interventions to support autistic women in reproductive health (FondaMental Advanced Center of Expertise for ASD (FACE-ASD) center of Grenoble).

Altogether, the results of this systematic review may be summarized as follows: (i) women report several unmet needs in the domains of romantic relationships and reproductive health; (ii) psychosocial treatment addressing skills related to romantic relationships remains underdeveloped and is often inadequate to women's needs for care; (iii) research on reproductive health and parenting in autistic mothers is almost inexistent, and there is a lack of interventions supporting future mothers or mothers with ASD; and (iv) stigma reduction could improve women's outcomes in romantic relationships and reproductive health.

While there are few gender differences in the pattern of service utilization, women report more unmet needs and more negative experiences with healthcare providers and social workers (22, 27). Compared with autistic men and typically developing women, women with ASD report more often comorbid physical health conditions (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome, 7.8 vs. 3.5% in the general population) (49) and less utilization of women's health services (OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.48–0.72) (50). The barriers to accessing adequate healthcare include providers' lack of knowledge and dedicated training regarding autistic women' needs for care and the lack of specific services for adults with ASD (22, 49, 50). Although it has been proposed that autistic women's lower access to women's health services could be explained by less frequent sexual experiences (50), several studies have reported the opposite (23, 24, 34). A higher motivation to engage in social relationships, a higher desire to fit in social contexts and to meet gender-related social expectations, preference for opposite-sex friendships, and increased use of camouflage strategies are characteristics often associated with female gender (32, 34, 51, 52).

Qualitative research reported that women found social relationships challenging and felt exhaustion or identity loss feelings when using camouflage strategies (32, 34, 51). Camouflaging refers to the use of conscious or unconscious strategies to minimize or mask autistic characteristics during a social interaction (1). Reasons for camouflaging include the desire to fit in a non-autistic world, anticipated stigma, concerns about the impression made when not camouflaging, and self-stigma (53). Cooper et al. (3) have reported that autistic women identified less with their gender group and had lower in-group value (i.e., one's perception of his own group) compared to autistic men and typically developing women. Hull et al. (1) have found an increased use of camouflage strategies in non-binary autistic individuals and women compared to autistic men. The negative effects of camouflaging strategies on psychiatric symptoms (i.e., higher psychological distress, anxiety, and depression) (53) might be more pronounced in this population (1).

SST is a group-based intervention that encompasses a set of behavioral strategies for teaching new skills based on social learning theory (54). Compensation strategies refer to the use of alternative cognitive routes to compensate for ASD-related social-cognitive difficulties (e.g., impairments in theory of mind) (55). They have been associated with higher verbal abilities, preserved executive function, and improved social skills, but also poorer mental health (56, 57). Although it has been proposed that compensation could be an adaptive coping strategy contributing to SST effectiveness on social skills, it may partially overlap with camouflaging (1, 56). SST could increase the use of camouflage strategies and indirectly contribute to increased psychological distress and suicidal ideation (1, 4, 58). To our knowledge, existing SST interventions do not address the distinction between compensation and camouflaging and their respective consequences on treatment outcomes and mental health. Future programs should address this distinction to improve compensation while reducing camouflaging (56, 57). SST also carries the risk of reinforcing common gender stereotypes about how a person should act in a given sociocultural context (4, 59). The inclusion of gender-sensitive content (e.g., discussing gender variance and gender-related social roles, norms, and expectations) in SST programs could prevent the internalization of gender social norms and improve treatment effectiveness in autistic women and gender-diverse individuals (4, 38).

Camouflaging has been related to secrecy coping and could be used to avoid the stigma of being labeled with ASD (60). Experienced stigma, anticipated stigma, and self-stigma were identified as barriers to intimacy in ASD (33). This concurs with findings in serious mental illness where self-stigma has been associated with reduced capacity for intimacy and more negative parenting experiences (61). Self-stigma has been found to affect one in five people with ASD (7, 62). It has been associated with poorer recovery-related outcomes (i.e., reduced self-esteem and well-being and higher depression and suicide risk) (7). Gender-diverse autistic individuals are confronted with multiple sources of stigma (e.g., intersection of ASD and gender identity stigma) and may be at particular risk of self-stigma (33). Future research should further investigate perceived stigma, experienced stigma, anticipated stigma, and self-stigma in gender-diverse autistic individuals. Self-stigma reduction [e.g., narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy (65) or peer-delivered interventions (61)] might improve the clinical and functional outcomes in autistic women, although this remains to be investigated. A longitudinal examination is needed to investigate the potential relationships between camouflage strategies, stigma-related issues, capacity for intimacy, and parenting experiences.

Cage and Troxell-Whitman (53) have found that autistic women were more likely than men to endorse “conventional reasons” for camouflaging (e.g., fitting in university or work contexts). Nagib and Wilton (66) have reported that gender-related assumptions about stereotypical jobs to which they should aspire limited autistic women in their vocational insertions. This might contribute to the lower satisfaction and benefits from vocational support services in autistic women compared with men (16, 22). Future research should investigate whether the integration of gender-sensitive content (i.e., taking into account gender variance and discussing gender-related sociocultural norms, roles, and expectations) in psychiatric rehabilitation (e.g., in cognitive behavior therapy) and vocational support services improves treatment outcomes or not.

Compared to non-autistic mothers, autistic mothers had higher risks of perinatal depression and poorer obstetrical and neonatal outcomes (27, 31). Clinical implications from qualitative research included a need for clear and accurate information (e.g., about normal pregnancy, potential complications, delivery, and post-partum care), for stigma reduction (e.g., reducing the feeling of being judged by perinatal health providers), and for improved self-agency and empowerment (27, 46, 47). Awareness actions toward women's health professionals could improve their understanding of autistic women's needs (e.g., heightened sensory processing and medical examinations) and reduce the stigma associated with autism (27, 46, 47). Strategic disclosure programs result in people making empowered decisions about whether to disclose their diagnosis or not (67). A strengths-based case management by a trained midwife, shared decision-making, and shared action plans during the perinatal period (i.e., from preconception to 1 year after childbirth) could improve self-agency, empowerment, and maternal and children's outcomes (68–70). Future studies should investigate the potential effectiveness of these interventions in ASD. In other conditions such as serious mental illness, mothers report concerns about passing on their condition to their children (71). This might also be the case for autistic mothers, although this should be further investigated. Psychoeducation and family psychoeducation (e.g., ASD and pregnancy-related outcomes, heredity, risk factors for perinatal depression and how to deal with them, early detection, and intervention of ASD in children) provided during the perinatal period could prevent perinatal depression and improve maternal and children's outcomes.

Psychiatric rehabilitation interventions on reproductive health should also discuss the centrality of motherhood for autistic women (or, in contrast, their self-reported “absence of maternal instinct”) (32) and its impact on a person's sense of personal identity.

Among the psychosocial interventions addressing romantic relationships or reproductive health in autistic people, no gender differences were reported on treatment outcomes after SST or psychosexual training (15, 17). Although it has been proposed that autistic women and men had similar needs for care and could benefit from the same interventions (15), autistic women may face unique challenges when subjective aspects (e.g., impact of gender-related social norms, roles, and expectations on a person's sense of identity) (32, 34) and specific domains (e.g., romantic relationships and reproductive health) (24, 26, 27, 34, 45) are considered.

While recent epidemiological studies have found lower male-to-female ratios than previously reported (18), the predominance of males in research samples could have affected both the development and the evaluation of psychosocial treatments (18, 19). It can be hypothesized that men, presumed to have poorer social function, are all referred to psychosocial treatment, whereas only the women with severe social communication impairments are referred (19). Another hypothesis could be that existing interventions (mostly developed in male samples) do not meet the unique needs for care of women and gender-diverse individuals (e.g., discussing gender variance and gender-related social norms, roles, and expectations, prevention of sexual abuse, and reproductive health) (4, 26, 44). The development of strengths-based, gender-sensitive (i.e., taking into account gender variance, autistic people's lived experience, and women's needs for care) interventions addressing romantic relationships and reproductive health is needed (4, 13).

There are some limitations to this review due to the heterogeneity in samples, in the methods, scales, interventions, and the reported outcomes. Few studies reported longitudinal outcomes, and only a small number of psychosocial treatments addressed romantic relationships or reproductive health from the perspective of autistic women or autistic gender-diverse individuals. The low–moderate quality of the included studies is also a limitation. This review excluded studies where women's outcomes in specific domains (i.e., romantic relationships and reproductive health) were not the main focus, which means that some needs for care in other domains (e.g., vocational function or leisure activities) might have been overlooked. However, by focusing on these domains using a broad definition of female gender (i.e., cisgender and gender-diverse individuals), this review provides a more accurate understanding of this population's needs for care relating to psychosocial treatments. The underreporting of negative or non-significant results due to publication bias from this review might have limited the accuracy of the synthesis.

In short, gender may influence a person's needs for care and treatment outcomes in autistic people, but this remains underinvestigated. Psychosocial treatments addressing romantic relationships or reproductive health remain underdeveloped and are often inadequate for women's and gender-diverse individuals' needs for care. High-quality research taking into account the perspectives and lived experiences of autistic women and gender-diverse individuals relating to their needs for care in romantic relationships and reproductive health is needed to guide the development of new interventions. Adopting a woman's health lens during the care of autistic women (e.g., with an evaluation and interventions by a trained midwife or by integrating gender-sensitive content in psychosocial treatments) might improve their access to physical healthcare services and to adequate support from perinatal services. This remains, however, to be investigated.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

MD and JD carried out the literature review and drafted the article. Both authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

This work was funded by the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Nouvelle-Aquitaine regional health agencies.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors are grateful to the reviewers of a previous version of the manuscript for their helpful comments.

1. Hull L, Petrides KV, Mandy W. The female autism phenotype and camouflaging: a narrative review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 7:306–17. doi: 10.3389/frym.2019.00129

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5), 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press (2013). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

3. Cooper K, Smith LGE, Russell AJ. Gender identity in autism: sex differences in social affiliation with gender groups. J Autism Dev Disord. (2018) 48:3995–4006. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3590-1

4. Strang JF, van der Miesen AI, Caplan R, Hughes C, daVanport S, Lai MC. Both sex- and gender-related factors should be considered in autism research and clinical practice. Autism. (2020) 24:539–543. doi: 10.1177/1362361320913192

5. Farkas M, Anthony WA. Psychiatric rehabilitation interventions: a review. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2010) 22:114–29. doi: 10.3109/09540261003730372

6. Franck N, Bon L, Dekerle M, Plasse J, Massoubre C, Pommier R, et al. Satisfaction and needs in serious mental illness and autism spectrum disorder: the REHABase psychosocial rehabilitation project. Psychiatr Serv. (2019) 70:316–23 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800420

7. Dubreucq J, Plasse J, Gabayet F, Faraldo M, Blanc O, Chereau I, et al. Self-stigma in serious mental illness and autism spectrum disorder: results from the REHABase national psychiatric rehabilitation cohort. Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 63:e13. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2019.12

8. Dandil Y, Smith K, Kinnaird E, Toloza C, Tchanturia K. Cognitive remediation interventions in autism spectrum condition: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:722. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00722

9. Mavranezouli I, Megnin-Viggars O, Cheema N, Howlin P, Baron-Cohen S, Pilling S. The cost-effectiveness of supported employment for adults with autism in the United Kingdom. Autism. (2014) 18:975–84. doi: 10.1177/1362361313505720

10. Keefer A, White SW, Vasa RA, Reaven J. Psychosocial interventions for internalizing disorders in youth and adults with ASD. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2018) 30:62–77. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1432575

11. Spain D, Blainey SH. Group social skills interventions for adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Autism. (2015) 19:874–86. doi: 10.1177/1362361315587659

12. Hillier A, Campbell H, Mastriani K, Izzo MV, Kool-Tukcer AK, Cherry L, et al. Two-year evaluation of a vocational support program for adults on the autism spectrum. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. (2007) 30:35–47 doi: 10.1177/08857288070300010501

13. DaWalt LS, Taylor JL, Bishop S, Hall LJ, Steinbrenner JD, Kraemer B, et al. Sex differences in social participation of high school students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. (2020) 13:2155–63. doi: 10.1002/aur.2348

14. Taylor JL, Henninger NA, Mailick MR. Longitudinal patterns of employment and postsecondary education for adults with autism and average-range IQ. Autism. (2015) 19:785–93. doi: 10.1177/1362361315585643

15. McVey AJ, Schiltz H, Haendel A, Dolan BK, Willar KS, Pleiss S, et al. Brief report: does gender matter in intervention for ASD? Examining the impact of the PEERS® social skills intervention on social behavior among females with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. (2017) 47:2282–9. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3121-5

16. Sung C, Sánchez J, Kuo HJ, Wang CC, Leahy MJ. Gender differences in vocational rehabilitation service predictors of successful competitive employment for transition-aged individuals with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. (2015) 45:3204–18. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2480-z

17. Visser K, Greaves-Lord K, Tick NT, Verhulst FC, Maras A, van der Vegt EJM. A randomized controlled trial to examine the effects of the Tackling Teenage psychosexual training program for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2017) 58:840–50. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12709

18. Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Auyeung B, Chakrabarti B, Baron-Cohen S. Sex/gender differences and autism: setting the scene for future research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2015) 54:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003

19. Dubreucq J, Haesebaert F, Plasse J, Dubreucq M, Franck N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social skills training for adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. Revised.

20. Laugeson EA, Gantman A, Kapp SK, Orenski K, Ellingsen R. A Randomized controlled trial to improve social skills in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: the UCLA PEERS(®) program. J Autism Dev Disord. (2015) 45:3978–89. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2504-8

21. Cunningham A, Sperry L, Brady MP, Peluso PR, Pauletti RE. The effects of a romantic relationship treatment option for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Counsel Outcome Res Eval. (2016) 7:99–110. doi: 10.1177/2150137816668561

22. Tint A, Weiss JA. A qualitative study of the service experiences of women with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. (2018) 22:928–37. doi: 10.1177/1362361317702561

23. Urbano MR, Hartmann K, Deutsch SI, Bondi Polychronopoulos GM, Dorbin V. Relationships, sexuality, and intimacy in autism spectrum disorders. In: Fitzgerald M, editor. Recent Advances in Autism Spectrum Disorders - Volume I. IntechOpen (2013). Available online at: https://www.intechopen.com/books/recent-advances-in-autism-spectrum-disorders-volume-i/relationships-sexuality-and-intimacy-in-autism-spectrum-disorders (accessed January 12, 2021).

24. Pecora LA, Hancock GI, Mesibov GB, Stokes MA. Characterising the sexuality and sexual experiences of autistic females. J Autism Dev Disord. (2019) 49:4834–46. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04204-9

25. George R, Stokes MA. A quantitative analysis of mental health among sexual and gender minority groups in ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. (2018) 48:2052–63. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3469-1

26. Taylor JL, DaWalt LS. Working toward a better understanding of the life experiences of women on the autism spectrum. Autism. (2020) 24:1027–30. doi: 10.1177/1362361320913754

27. Pohl AL, Crockford SK, Blakemore M, Allison C, Baron-Cohen S. A comparative study of autistic and non-autistic women's experience of motherhood. Mol Autism. (2020) 11:3. doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0304-2

28. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. (2015) 4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

29. Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O'Cathain A, Griffiths F, et al. Proposal: A Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for Systematic Mixed Studies Reviews. (2011). Available online at: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5tTRTc9yJ (accessed October 4, 2018).

30. Jamison TR, Schuttler JO. Overview and preliminary evidence for a social skills and self-care curriculum for adolescent females with autism: the girls night out model. J Autism Dev Disord. (2017) 47:110–25. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2939-6

31. Sundelin HE, Stephansson O, Hultman CM, Ludvigsson JF. Pregnancy outcomes in women with autism: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. (2018) 10:1817–1826. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S176910

32. Kanfiszer L, Davies F, Collins S. 'I was just so different': the experiences of women diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder in adulthood in relation to gender and social relationships. Autism. (2017) 21:661–9. doi: 10.1177/1362361316687987

33. Sala G, Hooley M, Stokes MA. Romantic intimacy in autism: a qualitative analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 50:4133–47. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04377-8

34. Bargiela S. Steward of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: an investigation of the female autism phenotype. J Autism Dev Disord. (2016) 46:3281–94. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8

35. Bejerot S, Eriksson JM. Sexuality and gender role in autism spectrum disorder: a case control study. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e87961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087961

36. Busch HH. Dimensions of sexuality among young women, with and without autism, with predominantly sexual minority identities. Sex Disabil. (2018) 37:275–92. doi: 10.1007/s11195-018-9532-1

37. Byers ES, Nichols S, Voyer SD, Reilly G. Sexual well-being of a community sample of high-functioning adults on the autism spectrum who have been in a romantic relationship. Autism. (2013) 17:418–33. doi: 10.1177/1362361311431950

38. Strang JF, Knauss M, van der Miesen A, McGuire JK, Kenworthy L, Caplan R, et al. A clinical program for transgender and gender-diverse neurodiverse/autistic adolescents developed through community-based participatory design. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2020) 6:1–16. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2020.1731817

39. Baldwin S, Costley D. The experiences and needs of female adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism. (2016) 20:483–95. doi: 10.1177/1362361315590805

40. Strunz S, Schermuck C, Ballerstein S, Ahlers CJ, Dziobek I, Roepke S. Romantic relationships and relationship satisfaction among adults with asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. J Clin Psychol. (2017) 73:113–25. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22319

41. Smith R, Netto J, Gribble NC, Falkmer M. 'At the end of the day, it's love': an exploration of relationships in neurodiverse couples. J Autism Dev Disord. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04790-z. [Epub ahead of print].

42. Corona LL, Fox SA, Christodulu KV, Worlock JA. Providing education on sexuality and relationships to adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and their parents. Sex Disabil. (2015) 34:199–214. doi: 10.1007/s11195-015-9424-6

43. Hénault I. Programme d'éducation sociosexuelle. In: Hénault I, editor. Sexualité et Syndrome d'Asperger, Éducation Sexuelle et Interventions Auprès de la Personne Autiste. Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck (2010), p. 115–20.

44. Dubreucq M, Dubreucq J. Recovery-oriented program on sexuality and prevention of sexual abuse for women with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): a new intervention based on a qualitative analysis. In preparation.

45. Pecora LA, Hancock GI, Hooley M, Demmer DH, Attwood T, Mesibov GB, et al. Gender identity, sexual orientation and adverse sexual experiences in autistic females. Mol Autism. (2020) 11:57. doi: 10.1186/s13229-020-00363-0

46. Gardner M, Suplee PD, Bloch J, Lecks K. Exploratory study of childbearing experiences of women with asperger syndrome. Nurs Womens Health. (2016) 20:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2015.12.001

47. Rogers C, Lepherd L, Ganguly R, Jacob-Rogers S. Perinatal issues for women with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Women Birth. (2017) 30:e89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.09.009

48. Donovan J. Childbirth experiences of women with autism spectrum disorder in an acute care setting. Nurs Womens Health. (2020) 24:165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2020.04.001

49. Kassee C, Babinski S, Tint A, Lunsky Y, Brown HK, Ameis SH, et al. Physical health of autistic girls and women: a scoping review. Mol Autism. (2020) 11:84. doi: 10.1186/s13229-020-00380-z

50. Ames JL, Massolo ML, Davignon MN, Qian Y, Croen LA. Healthcare service utilization and cost among transition-age youth with autism spectrum disorder and other special healthcare needs. Autism. (2020). doi: 10.1177/1362361320931268. [Epub ahead of print].

51. Milner V, McIntosh H, Colvert E, Happé F. A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. (2019) 49:2389–402. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

52. Sedgewick F, Hill V, Pellicano E. 'It's different for girls': gender differences in the friendships and conflict of autistic and neurotypical adolescents. Autism. (2019) 23:1119–32. doi: 10.1177/1362361318794930

53. Cage E, Troxell-Whitman Z. Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. (2019) 49:1899–911. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x

54. Moody CT, Laugeson EA. Social skills training in autism spectrum disorder across the lifespan. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2020) 29:359–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2019.11.001

55. Livingston LA, Happé F. Conceptualising compensation in neurodevelopmental disorders: Reflections from autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2017) 80:729–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.005

56. Livingston LA, Colvert E, Social Relationships Study Team, Bolton P, Happé F. Good social skills despite poor theory of mind: exploring compensation in autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2019) 60:102–10. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12886

57. Livingston LA, Shah P, Happé F. Compensatory strategies below the behavioural surface in autism: a qualitative study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:766–77. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30224-X

58. Cassidy SA, Gould K, Townsend E, Pelton M, Robertson AE, Rodgers J. Is camouflaging autistic traits associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours? Expanding the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide in an undergraduate student sample. J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 50:3638–48. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04323-3

59. Tint A, Hamdani Y, Sawyer A, Desarkar P, Ameis SH, Bardikoff N, et al. Wellness efforts for autistic women. Curr Dev Disord Rep. (2018) 5:207–16. doi: 10.1007/s40474-018-0148-z

60. Schneid I, Raz AE. The mask of autism: social camouflaging and impression management as coping/normalization from the perspectives of autistic adults. Soc Sci Med. (2020) 248:112826. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112826

61. Dubreucq J, Plasse J, Franck N. Self-stigma in serious mental illness: a systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophr Bull. (2021). doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa181. [Epub ahead of print].

62. Bachmann CJ, Höfer J, Kamp-Becker I, Küpper C, Poustka L, Roepke S, et al. Internalised stigma in adults with autism: a German multi-center survey. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 276:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.023

63. Turner D, Briken P, Schöttle D. Sexual dysfunctions and their association with the dual control model of sexual response in men and women with high-functioning autism. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:425. doi: 10.3390/jcm8040425

64. Barnett JP, Maticka-Tyndale E. Qualitative exploration of sexual experiences among adults on the autism spectrum: implications for sex education. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. (2015) 47:171–9. doi: 10.1363/47e5715

65. Yanos PT, Lysaker PH, Silverstein SM, Vayshenker B, Gonzales L, West ML, et al. A randomized-controlled trial of treatment for self-stigma among persons diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2019) 54:1363–78. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01702-0

66. Nagib W, Wilton R. Gender matters in career exploration and job-seeking among adults with autism spectrum disorder: evidence from an online community. Disabil Rehabil. (2020) 42:2530–41. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1573936

67. Mulfinger N, Müller S, Böge I, Sakar V, Corrigan PW, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Honest, open, proud for adolescents with mental illness: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2018) 59:684–91. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12853

68. Hauck Y, Rock D, Jackiewicz T, Jablensky A. Healthy babies for mothers with serious mental illness: a case management framework for mental health clinicians. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2008) 17:383–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00573.x

69. Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, Humberstone V, Jablensky A, Killackey E, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand college of psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2016) 50:410–72. doi: 10.1177/0004867416641195

70. Dubreucq M, Provasi A, Baudrant M, Dubreucq J. Development of a shared decision-making tool from preconception to post-partum care for women with serious mental illness: a qualitative analysis. In preparation.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, women, gender-diverse, unmet needs, psychiatric rehabilitation

Citation: Dubreucq M and Dubreucq J (2021) Toward a Gender-Sensitive Approach of Psychiatric Rehabilitation in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Systematic Review of Women Needs in the Domains of Romantic Relationships and Reproductive Health. Front. Psychiatry 12:630029. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.630029

Received: 17 November 2020; Accepted: 15 March 2021;

Published: 28 April 2021.

Edited by:

Asma Bouden, Tunis El Manar University, TunisiaReviewed by:

Yoon Phaik Ooi, University of Basel, SwitzerlandCopyright © 2021 Dubreucq and Dubreucq. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marine Dubreucq, bWFyaW5lLmJlbmVAaG90bWFpbC5mcg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.