- 1Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia

- 2Department of Nursing, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, South Korea

Background: Depression and hope are considered pivotal variables in the recovery process of people with schizophrenia.

Aim: This study examined the moderating effect of depression on the relationship between hope and recovery, and the mediating effect of hope on the relationship between depression and recovery in persons with schizophrenia.

Methods: The model was tested empirically using the data of 115 persons with schizophrenia from Central Java Province, Indonesia. The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia Hope Scale-9, and Recovery Assessment Scale were used to measure participants' depression, hope, and recovery, respectively.

Results: The findings supported the hypothesis that depression moderates the relationship between hope and recovery, and hope mediates the relationship between depression and recovery.

Conclusions: The findings suggest that mental health professionals need to focus on instilling hope and reducing depression to help improve the recovery of persons with schizophrenia. Furthermore, mental health professionals should actively develop and implement programs to instill hope and continuously evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions, particularly in community-based and in-patient mental health settings.

Introduction

Globally, schizophrenia is a serious mental illness that places a prolonged burden on people of all ages and both sexes (1). The diagnosis of mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, in Indonesia rose to 7.0% per million in 2018 from 1.7% per million in 2013 (2).

The prominent symptoms of schizophrenia include hallucinations, delusions, social withdrawal, and lack of motivation (3); however, persons with schizophrenia are also likely to experience depression (4–6). Previous studies on schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder found that 31–59% of participants experienced depression (7–9).

Depression is common in persons with schizophrenia; however, it is underdiagnosed and undertreated (5, 9, 10). Of concern, depression in persons with schizophrenia is a significant predictor of suicidal ideation (11) and suicide (5, 9, 12). Additionally, depression lowers the quality of life of persons with schizophrenia (13, 14). Thus, depression could be a barrier to the recovery of persons with schizophrenia, whereas hope could be used to support their recovery process (15).

Recovery is a process in which an individual with mental illness finds meaning and builds a life beyond their illness (16). Hope plays an important role in the recovery of persons with mental illnesses (17, 18). Previous studies found that a high level of hope was associated with a high quality of life in persons with schizophrenia (14, 19). Moreover, depression indirectly mediated the relationship between hope and quality of life (20).

According to the illness identity model (21, 22), a stigmatized view of mental illness diminishes hope and self-esteem, which induces detrimental effects, such as depressed mood and suicidal ideation, and eventually hinders recovery among people with severe mental illnesses. The model suggests that hope and depression are crucial variables in the recovery process of persons with schizophrenia. To the best of our knowledge, little is known about the moderating effect of depression and the mediating effect of hope on recovery. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the moderating effect of depression on the relationship between hope and recovery, and the mediating effect of hope on the relationship between depression and recovery in persons with schizophrenia in Indonesia.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study used a cross-sectional design. Persons with schizophrenia were recruited through convenience sampling from psychiatric hospitals in Central Java Province, Indonesia. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged 18–60; (2) diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (3); (3) psychological stability to answer the questionnaires (as determined by the medical staff); and (4) being able to provide informed consent voluntarily. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) intellectual disability or organic mental disorder and (2) worsening of psychotic symptoms during the data collection period. All participants in this study were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

Instruments

Socio-Demographic Questionnaire

The socio-demographic questionnaire included items on age, sex, marital status, education, occupational status, religion, and diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Depression

Depression was measured using the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) (23). The CDSS is an observer-rated interview-based instrument comprising nine items: depression, hopelessness, self-depreciation, guilty ideas of reference, pathological guilt, morning depression, early wakening, suicide, and observed depression. Each item is rated on a four-point scale (0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) with a score range of 0–27. The CDSS is the most reliable and valid measurement of depressive symptoms in persons with schizophrenia (24). For this scale, Cronbach's alpha was 0.81.

Hope

Hope was measured using the Schizophrenia Hope Scale-9 (SHS-9) (25). The SHS-9 measures hope in persons with schizophrenia based on three dimensions: positive expectations for the future, confidence in life and the future, and meaning in life. This self-reported scale consists of nine items on a three-point scale (0 = disagree, 1 = agree, 2 = strongly agree). Participants can score between 0–18, with higher scores indicating higher levels of hope. For this scale, Cronbach's alpha was 0.91.

Recovery

The 24-item Recovery Assessment Scale-revised (RAS-R), derived from the original 41-item scale (26), is a self-administered questionnaire that includes five factors: personal confidence and hope, willingness to ask for help, goals and success orientation, reliance on others, and no domination by symptoms. This questionnaire uses a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) to evaluate the recovery status of persons with a mental illness, such as schizophrenia (score range = 24–120). For this scale, Cronbach's alpha was 0.90.

Data Collection

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Faculty of Medicine, Diponegoro University (No. 351/EC/FK-RSDK/V/2018). Data collection was conducted from April to June 2018 by the authors who visited the psychiatric hospitals to administer the questionnaire and the scales. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The questionnaire took 10 min on average to complete. After 28 participants were removed from the data due to incomplete questionnaires, the data of 115 participants were statistically analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants were reported in terms of frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations (SD). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to examine the normal distribution of the quantitative variables; the total scores on the CDSS and SHS-9 were not normally distributed (p < 0.05). Therefore, we used the Mann–Whitney U-test to compare the groups. The scores of the RAS-R showed a normal distribution for sex and marital status; therefore, a t-test was used to analyze the difference between the two groups. Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the association between the scores. Subsequently, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to test whether depression moderated the relationship between hope and recovery. Interaction terms hope (SHS-9) × depression (CDSS) were created and entered after adjusting for control variables. The statistical significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

General Characteristics and Univariate Analyses

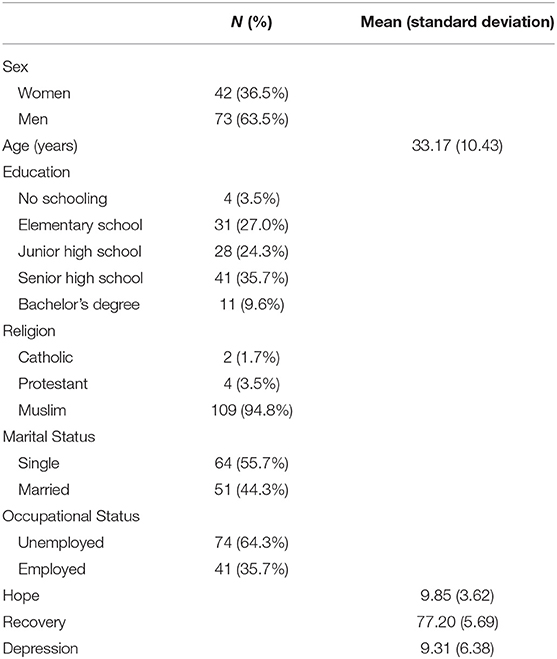

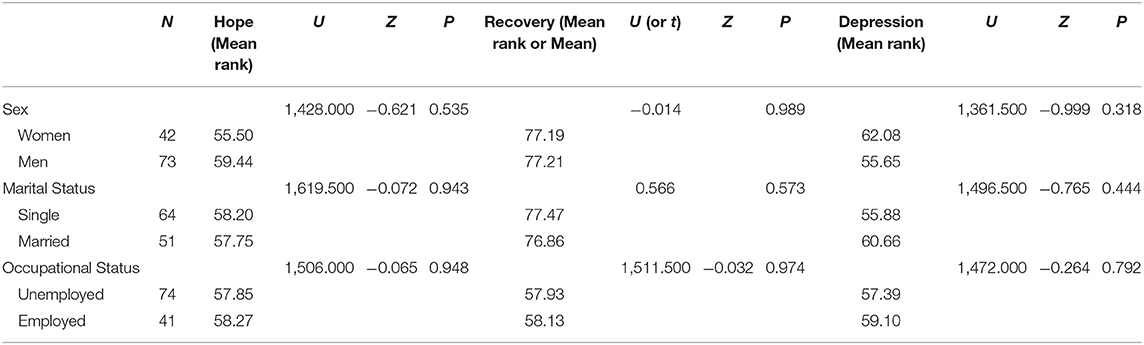

Of the 115 participants, 73 (63.5%) were men and 42 (36.5%) were women. The mean age was 33.17 years (range: 18–70 years). Of the total participants, 30.5% had an educational level lower than elementary school, 94.8% identified as Muslim, 55.7% were single, and 64.3% were unemployed (Table 1). The mean scores of hope, recovery, and depression were 9.85 (SD = 3.62), 77.20 (SD = 5.69), and 9.31 (SD = 6.38), respectively (Table 1). There was no significant difference in hope, recovery, and depression according to participants' sex, marital status, and occupational status (Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate analyses between demographic characteristics, hope, recovery, and depression (N = 115).

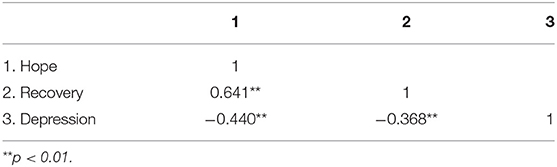

Correlation Analysis

A strong positive correlation was found between hope and recovery (r = 0.641, p < 0.001), while negative correlations were found between hope and depression (r = −0.440, p < 0.001) and recovery and depression (r = −0.368, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

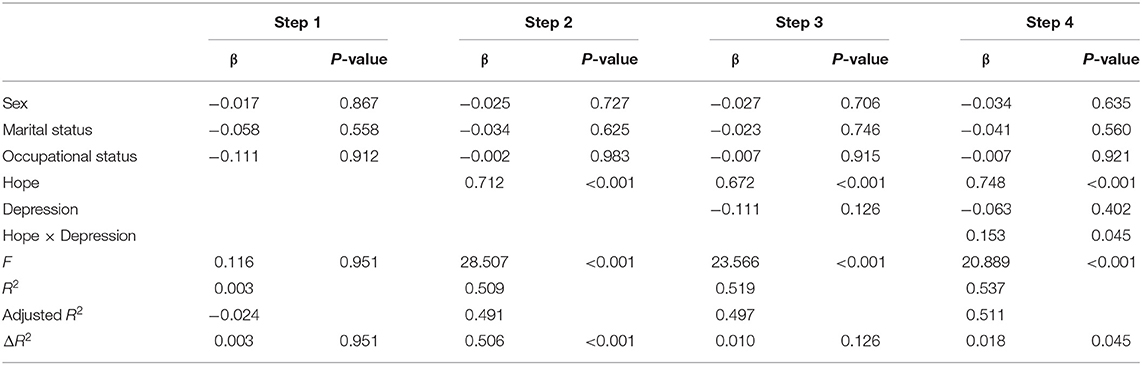

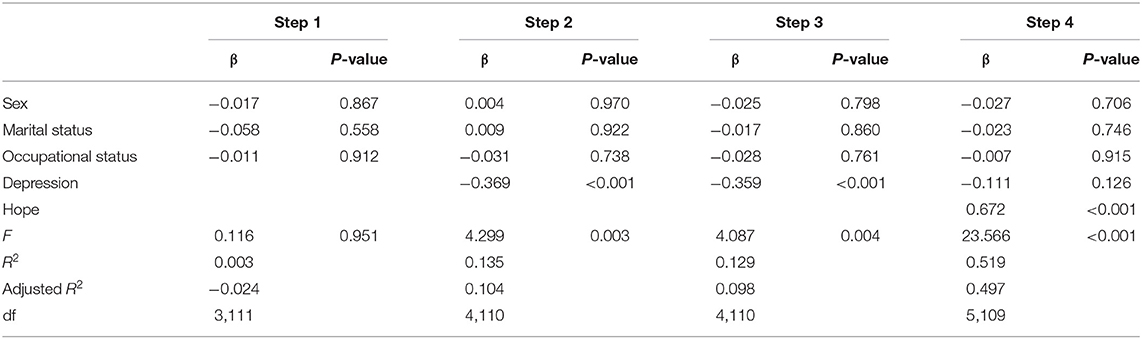

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

As hypothesized, depression moderated the relationship between hope and recovery. The interaction effect of depression on the relationship between hope and recovery was statistically significant (β = 0.153, p = 0.045). The power was 53.7% in model 4 (Table 4). Therefore, depression had a moderating effect on the relationship between hope and recovery.

As shown in Table 5, hope mediated the relationship between depression and recovery. On the second step, depression significantly predicted hope (β = −0.369, p < 0.001). On the third step, depression also significantly predicted recovery (β = −0.359, p < 0.001). On the fourth step, depression and hope were added; depression did not predict recovery (β = −0.111, p = 0.126), but hope significantly predicted recovery (β = 0.672, p < 0.001). Therefore, hope had a mediating effect on the relationship between depression and recovery. The statistical significance of the mediation effect was assessed using the Sobel test (z = −3.78, p < 0.001).

Discussion

In the current study, we examined the moderating effect of depression and the mediating effect of hope on the recovery process among persons with schizophrenia in Central Java Province, Indonesia. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the moderating effect of depression and the mediating effect of hope on the recovery of persons with schizophrenia. In this study, depression moderated the relationship between hope and recovery, and hope mediated the relationship between depression and recovery. The findings of this study reaffirm the influential roles of hope and depression in the recovery of persons with schizophrenia.

Hope and optimism about the future and meaning in life, including quality of life, are central themes of the recovery process in mental health (27). Not surprisingly, persons with mental illnesses who have a high level of hope have a high quality of life (14, 19). Sustaining hope by renewing it is an important process in recovery (16). Conversely, a lack of hope is associated with a low quality of life in persons with serious mental illnesses (28). Furthermore, hopelessness significantly mediates the relationship between symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation (11).

Depression is a significant predictor of psychological well-being, such as purpose in life, in persons with schizophrenia (29). Expectedly, in this study, depression affected recovery, and it was negatively correlated with hope and recovery: higher the levels of recovery in relation to hope and personal confidence, fewer the psychiatric symptoms (30). Therefore, researchers need to explore positive factors that contribute to hope and reduce depression. Mental health professionals working in the community need to increase their efforts to enhance and maintain hope as well as reduce depression in persons with schizophrenia.

The results showed that there was no significant difference in hope, depression, and recovery according to sex, marital status, and occupational status. It is generally reported that women have more depressive symptoms than men (31). Our findings are similar to those of previous studies that show that more participants with schizophrenia were men than women, unemployed than employed, and Muslims than members of other religions (8, 32). However, the effect of the general characteristics of participants with schizophrenia on recovery has not been studied sufficiently. Further studies are needed to explore how the general characteristics of persons with schizophrenia, such as sex, educational background, marital status, and occupational status, affect their hope and recovery in Indonesia.

This study had some limitations. We collected data from patients with schizophrenia admitted to some psychiatric hospitals in Central Java Province, Indonesia. Therefore, one needs to be careful while generalizing these findings for other populations. When designing this study, we did not adequately consider other contextual factors (e.g., the length of hospital stay, duration of illness, type of occupation, family presence) that could affect participants' depression, hope, and recovery.

Clinical Implications

This study demonstrates that maintaining and enhancing hope while paying attention to depression is essential for the recovery of persons with schizophrenia. For them, recovery is about having a sense of identity to grow beyond their illness while discovering their strength and ability to pursue personal goals (33). Most of all, hope is a pivotal factor in enhancing recovery in persons with schizophrenia. Therefore, mental health professionals should actively develop and implement psychotherapies to instill hope and reduce depression, continuously evaluate the effectiveness of such interventions, and improve services, particularly in community-based and inpatient mental health settings.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Diponegoro University (No. 351/EC/FK-RSDK/V/2018). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SS, MA, and KC contributed to the conception and design of the study. DW, WS, and UA organized the database. KC performed the statistical analyses. SS and KC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised, read, and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chung-Ang University Research Scholarship Grants in 2019.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants with schizophrenia for their participation in this study.

Abbreviations

CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; SHS-9, Schizophrenia Hope Scale-9; RAS-R, Recovery Assessment Scale-Revised.

References

1. Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392:1736–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

2. Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. Basic Health Research Results (Riskesdas). (2018). Available online at: http://kesmas.kemkes.go.id/assets/upload/dir_519d41d8cd98f00/files/Hasil-riskesdas-2018_1274.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing (2013). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

4. Chiappelli J, Nugent KL, Thangavelu K, Searcy K, Hong LE. Assessment of trait and state aspects of depression in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2014) 40:132–42. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt069

5. Moritz S, Schröder J, Klein JP, Lincoln TM, Andreou C, Fischer A, et al. Effects of online intervention for depression on mood and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2016) 175:216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.04.033

6. Nasrallah HA, Cucchiaro JB, Mao Y, Pikalov AA, Loebel AD. Lurasidone for the treatment of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: analysis of 4 pooled, 6-week, placebo-controlled studies. CNS Spectr. (2015) 20:140–47. doi: 10.1017/S1092852914000285

7. Majadas S, Olivares J, Galan J, Diez T. Prevalence of depression and its relationship with other clinical characteristics in a sample of patients with stable schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. (2012) 53:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.03.009

8. Sari SP, Dwidiyanti M, Wijayanti DY, Sarjana W. Prevalence, demographic, clinical features and its association of comorbid depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil. (2017) 21:99–110.

9. Upthegrove R, Ross K, Brunet K, McCollum R, Jones L. Depression in first episode psychosis: the role of subordination and shame. Psychiatry Res. (2014) 217:177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.023

10. Bosanac P, Castle DJ. Schizophrenia and depression. Med J Aust. (2013) 199:S36–9. doi: 10.5694/mjao12.10516

11. Bornheimer LA. Moderating effects of positive symptoms of psychosis in suicidal ideation among adults diagnosed with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2016) 176:364–70. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.009

12. Yoo T, Kim SW, Kim SY, Lee JY, Kang HJ, Bae KY, et al. Relationship between suicidality and low self-esteem in patients with schizophrenia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. (2015) 13:296–301. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.3.296

13. Staring ABP, Van der Gaag M, Van den Berge M, Duivenvoorden HJ, Mulder CL. Stigma moderates the associations of insight with depressed mood, low self-esteem, and low quality of life in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. (2009) 115:363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.015

14. Vrbova K, Prasko J, Ociskova M, Kamaradova D, Marackova M, Holubova M, et al. Quality of life, self-stigma, and hope in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2017) 13:567–76. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S122483

15. Lagger N, Amering M, Sibitz I, Gmeiner A, Schrank B. Stability and mutual prospective relationships of stereotyped beliefs about mental illness, hope and depressive symptoms among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 268:484–89. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.010

16. Wyder M, Bland R, Crompton D. Personal recovery and involuntary mental health admissions: the importance of control, relationships and hope. Health. (2013) 5:574–81. doi: 10.4236/health.2013.53A076

17. Hobbs M, Baker M. Hope for recovery–how clinicians may facilitate this in their work. J Ment Health. (2012) 21:144–53. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.648345

18. Schrank B, Hayward M, Stanghellini G, Davidson L. Hope in psychiatry. Adv Psychiatr Treat. (2011) 17:227–35. doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.109.007286

19. Hayes L, Herrman H, Castle D, Harvey C. Hope, recovery and symptoms: the importance of hope for people living with severe mental illness. Australas Psychiatry. (2017) 25:583–87. doi: 10.1177/1039856217726693

20. Wang WL, Zhou YQ, Chai NN, Li GH, Liu DW. Mediation and moderation analyses: exploring the complex pathways between hope and quality of life among patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:22. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-2436-5

21. Yanos PT, DeLuca JS, Roe D, Lysaker PH. The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112950. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112950

22. Yanos PT, Roe D, Lysaker PH. The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2010) 13:73–93. doi: 10.1080/15487761003756860

23. Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the calgary depression scale. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. (1993) 163:39–44. doi: 10.1192/S0007125000292581

24. Lako IM, Bruggeman R, Knegtering H, Wiersma D, Schoevers RA, Slooff CJ, et al. A systematic review of instruments to measure depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. (2012) 140:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.014

25. Choe K. Development and preliminary testing of the schizophrenia hope scale, a brief scale to measure hope in people with schizophrenia. Int J Nurs Stud. (2014) 51:927–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.10.018

26. Corrigan PW, Salzer M, Ralph RO, Sangster Y, Keck L. Examining the factor structure of the recovery assessment scale. Schizophr Bull. (2004) 30:1035–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007118

27. Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry. (2011) 199:445–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

28. Mashiach-Eizenberg M, Hasson-Ohayon I, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH, Roe D. Internalized stigma and quality of life among persons with severe mental illness: the mediating roles of self-esteem and hope. Psychiatry Res. (2013) 208:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.013

29. Strauss GP, Sandt AR, Catalano LT, Allen DN. Negative symptoms and depression predict lower psychological well-being in individuals with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. (2012) 53:1137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.05.009

30. Kukla M, Lysaker PH, Salyers MP. Do persons with schizophrenia who have better metacognitive capacity also have a stronger subjective experience of recovery? Psychiatry Res. (2013) 209:381–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.04.014

31. Shors TJ, Millon EM, Chang HYM, Olson RL, Alderman BL. Do sex differences in rumination explain sex differences in depression? J Neurosci Res. (2017) 95:711–718. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23976

32. Pribadi T, Lin ECL, Chen PS, Lee SK, Fitryasari R, Chen CH. Factors associated with internalized stigma for Indonesian individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia in a community setting. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 27:584–94. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12611

Keywords: depression, hope, moderating effect, recovery, schizophrenia depression, mediating effect

Citation: Sari SP, Agustin M, Wijayanti DY, Sarjana W, Afrikhah U and Choe K (2021) Mediating Effect of Hope on the Relationship Between Depression and Recovery in Persons With Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 12:627588. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.627588

Received: 09 November 2020; Accepted: 18 January 2021;

Published: 09 February 2021.

Edited by:

Elisa C. Dias, Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, United StatesReviewed by:

Massimo Tusconi, University of Cagliari, ItalyDiane Carol Gooding, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States

Copyright © 2021 Sari, Agustin, Wijayanti, Sarjana, Afrikhah and Choe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kwisoon Choe, a3dpc29vbmNob2VAY2F1LmFjLmty

Sri Padma Sari

Sri Padma Sari Murti Agustin

Murti Agustin Diyan Yuli Wijayanti

Diyan Yuli Wijayanti Widodo Sarjana1

Widodo Sarjana1 Umi Afrikhah

Umi Afrikhah Kwisoon Choe

Kwisoon Choe