- 1Divison of Life Sciences, Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana, Bengaluru, India

- 2Department of Neurology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

- 3Centre for Mind Body Medicine, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

- 4Centre of Phenomenology and Cognitive Sciences, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India

- 5College of Health and Behavioral Sciences, Fort Hays State University, Hays, KS, United States

- 6Department of General Medicine, Dr. Pinnamaneni Siddhartha Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Foundation, Chinna-Avutapalli, India

- 7Division of Yoga and Physical Sciences, Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana, Bengaluru, India

Uncertainty about Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and resulting lockdown caused widespread panic, stress, and anxiety. Yoga is a known practice that reduces stress and anxiety and may enhance immunity. This study aimed to (1) investigate that including Yoga in daily routine is beneficial for physical and mental health, and (2) to evaluate lifestyle of Yoga practitioners that may be instrumental in coping with stress associated with lockdown. This is a pan-India cross-sectional survey study, which was conducted during the lockdown. A self-rated scale, COVID Health Assessment Scale (CHAS), was designed by 11 experts in 3 Delphi rounds (Content valid ratio = 0.85) to evaluate the physical health, mental health, lifestyle, and coping skills of the individuals. The survey was made available digitally using Google forms and collected 23,760 CHAS responses. There were 23,290 valid responses (98%). After the study's inclusion and exclusion criteria of yogic practices, the respondents were categorized into the Yoga (n = 9,840) and Non-Yoga (n = 3,377) groups, who actively practiced Yoga during the lockdown in India. The statistical analyses were performed running logistic and multinomial regression and calculating odds ratio estimation using R software version 4.0.0. The non-Yoga group was more likely to use substances and unhealthy food and less likely to have good quality sleep. Yoga practitioners reported good physical ability and endurance. Yoga group also showed less anxiety, stress, fear, and having better coping strategies than the non-Yoga group. The Yoga group displayed striking and superior ability to cope with stress and anxiety associated with lockdown and COVID-19. In the Yoga group, participants performing meditation reportedly had relatively better mental health. Yoga may lead to risk reduction of COVID-19 by decreasing stress and improving immunity if specific yoga protocols are implemented through a global public health initiative.

Introduction

WHO declared Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), originating from Wuhan, China, caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2), as a pandemic on March 11, 2020. To prevent spread and provide sufficient time for hospitals' readiness, the Governments worldwide had to impose “Lockdown” in their respective countries. Under lockdown, people were restricted from remaining outdoors with certain exceptions resulting from emergencies.

India imposed the world's most extensive lockdown on March 23, 2020 (1). Many people were either stranded in their homes or containment zones, disrupting small businesses' earnings, working of domestic maids, daily wagers, and laborers. In addition, the uncertainty of the disease's contagious nature among the public and healthcare workers led to fear, panic, anxiety, and stress. Stress also intensified among those with chronic illnesses, as susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 were associated with co-morbidities (2–4). Furthermore, global infodemic and fake news exasperated anxiety and stress among the general public (5, 6).

Previous studies have evidenced increased post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after epidemic or natural calamities such as SARS, earthquake, or a tornado, including COVID-19 (7–10). Wang et al. conducted a comprehensive self-administered online survey in China to understand the prevalence of psychological stress in the COVID-19 pandemic. They reported increased panic, stress, anxiety, and depression similar to previous studies conducted during the 2003 SARS epidemic (7, 8, 11). A similar online survey by Liu et al. reported that 20% of people showed anxiety, 27% reported depression, 7.7% had psychological distress, and 10% suffered from phobias (12). Furthermore, there were changes in people's behavioral patterns due to lockdown, especially concerning their eating habits. Increased consumption of junk food, soft drinks, and alcohol resulted in obesity. Lockdown disrupted the daily routines, sleep hours, outdoor activities, and increased screen time and smoking, predisposing people to risks of COVID-19 (13, 14). Two small studies from India have shown similar trends (15, 16).

In the current study on the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been reported that the impact on psychological stress might be more pronounced due to persistent global media feeds and internet access. The present COVID Health Assessment Scale (CHAS) survey was designed to evaluate the physical and mental health and coping skills of participants who practiced yoga and those who did not. Several studies have shown that Yoga brings a positive change in physical and mental health by regulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system, sympathetic nervous system, reducing the cortisol, and improving immunity indicated by an increase in CD4, heart rate, fasting blood glucose, cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein levels (17–20). Thus, it appears that Yoga practitioners have healthy lifestyle among the general population. This study investigated that including Yoga in daily routine is beneficial for physical and mental health. Also, Yoga practitioners have a healthier lifestyle, which improves their ability to cope with the restrictions and stress under lockdown.

Materials and Methods

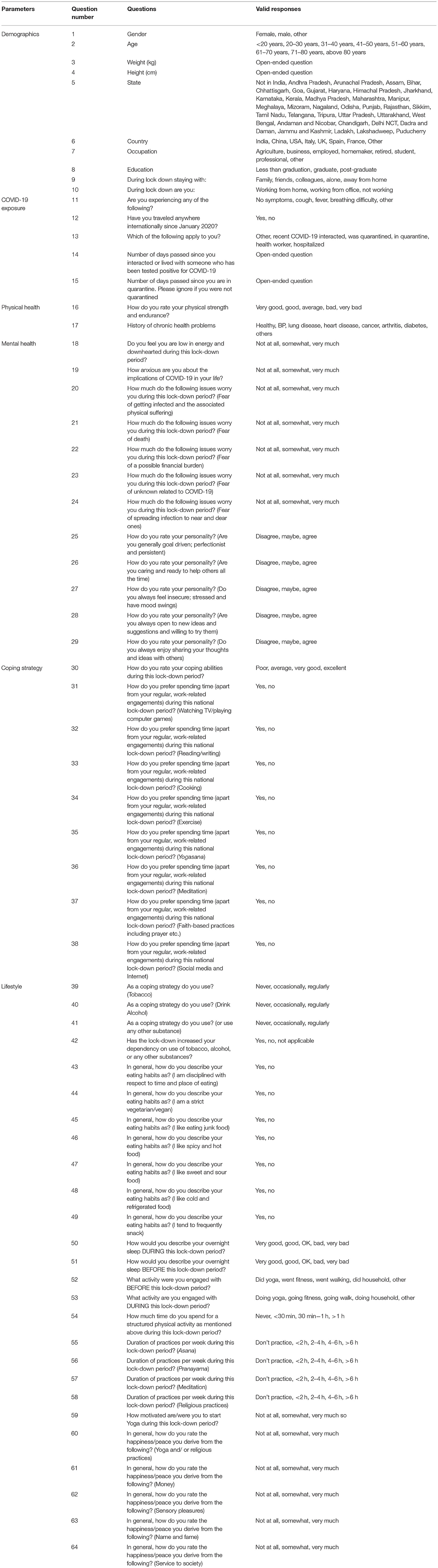

The current study received ethical approval from Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana (S-VYASA) University, Karnataka, India. CHAS, a unique self-assessment scale, was designed for the survey in 10 different languages, English, Hindi, Assamese, Bengali, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Odia, Tamil, and Telugu. A committee consisting of 11 experts was constituted who undertook three rounds of discussions as per Delphi protocol and agreed to the CHAS questionnaire that assessed the positive and negative aspects of physical and mental health, lifestyle, and associated coping methods during the lockdown period (Table 1). Among 11 experts, 6 had PhD in Yoga with more than 15 years of experience in yoga research, 3 were post-graduate in yoga with experience of more than 10 years in yoga, one is a professor of statistics, a mathematician with masters in psychology and PhD in yoga, and one is a psychologist with PhD in yoga. Content valid ratio (CVR) was 0.85 for CHAS as per Delphi method (21–23). CHAS also collected the demographic (questions 1–10) and lifestyle (questions 39–64) details of the participants.

Questions 11–15 accessed COVID-19 exposure of participants; these included self-reported symptoms, travel history, details of interaction with COVID-19–positive patient, and quarantine history. Physical health was accessed by rating physical strength and endurance (question 16) and disease history (question 17). In question 16, two extreme options were considered as a single option during analysis.

Twelve questions (questions 18–29) were included in CHAS to assess the mental health during the lockdown. The questions were designed to evaluate fear and anxiety during the lockdown and evaluate the individual's general personality or character. Standard neuropsychological questionnaires were not used to evaluate stress and anxiety.

The coping ability of participants was accessed by a direct question with four options, i.e., “Poor,” “Average,” “Very good,” and “Excellent” (question 30). During analysis, “Poor” and “Average” were merged into a single attribute, i.e., “Poor.” Similarly, “Very Good” and “Excellent” were merged to constitute “Good.” Questions 31–38 enquired about different activities of participants during lockdown; these questions indicate coping strategy of participants during lockdown. Questions 39–42 in lifestyle domain also provide information on coping strategy.

Data Collection and Study Participants

The survey items for CHAS were prepared on Google forms and circulated in public through social media. Snowball method was used to acquire the data nationwide. Phone calls and special requests were sent to different sections of the society (~200 universities, Corporate companies, healthcare institutions, government organizations, wellness centers, and their networks) to acquire data within this short period. No inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined during the circulation of CHAS. Hence, the received responses showed diversity in age, gender, occupation, education, and other demographics (Table 2). This study was sponsored and conducted by S-VYASA. The participation was voluntary, and the response sheets were downloaded daily.

The CHAS data were collected between May 9, 2020 and May 31, 2020, and 23,760 responses were received. Incomplete and unreliable responses, respondents from outside of India and respondents aged <18 years were excluded (n = 470). The remaining 23,290 responses were evaluated to assign participants in Yoga and non-Yoga groups. Inclusion criteria were age should be ≥18 years and all respondents should be residing in India. Yoga and non-Yoga group was defined according to the responses of question numbers 52, 53, 55, 56, and 57 of the CHAS questionnaire (Table 1).

Criteria for Defining Yoga Group

The Yoga group was defined as individuals who performed Yoga both before (question 52) and during (question 53) the lockdown, which included practicing one or more among Asanas (question 55) (Yoga postures), Pranayama (Yogic breathing exercises) (question 56), and meditation (question 57) for a few hours to more than 6 h per week during the lockdown. Participants, who replied “Did Yoga” for questions 52 and 53, but marked “Don't practice” for questions 55–57 were excluded from the Yoga group. According to these criteria, 9,840 participants qualified for the Yoga group.

Furthermore, the Yoga group was divided into four sub-groups, i.e., Yoga practitioners who practiced Asana, Pranayama, and meditation (all three together; n = 6,156), practitioners who practiced only Asana (n = 149), only Pranayama (n = 89), and only meditation (n = 1,485). The combination of two practices among Asana, Pranayama, and meditation was not considered as a sub-group.

Criteria for Defining Non-Yoga Group

The non-Yoga group included respondents who did not perform Yoga before (question 52) or during (question 53) the lockdown and replied “Don't Practice” for the questions on Asana (question 55), Pranayama (question 56), and meditation (question 57). Following the aforementioned inclusion criteria, 3,377 participants were accepted in the non-Yoga group.

Statistical Analysis

R Statistical software, version 4.0.0, was used for data cleaning, extraction, and analyses. The arsenal package in R was used to determine cross-tabulations and χ2 test; logistic and multinomial regression was used. Age, gender, occupation, education, and working status during lockdown were used as covariates.

The dependent variables were the study groups. We used multiple predictors in each of the regression models. Sequential contrast was used for ordinal variables. The predictors were selected based on the domains presented in the survey. The domains were demographic details, physical health, mental health, coping strategy, and lifestyle.

Results

Demographic Characterization

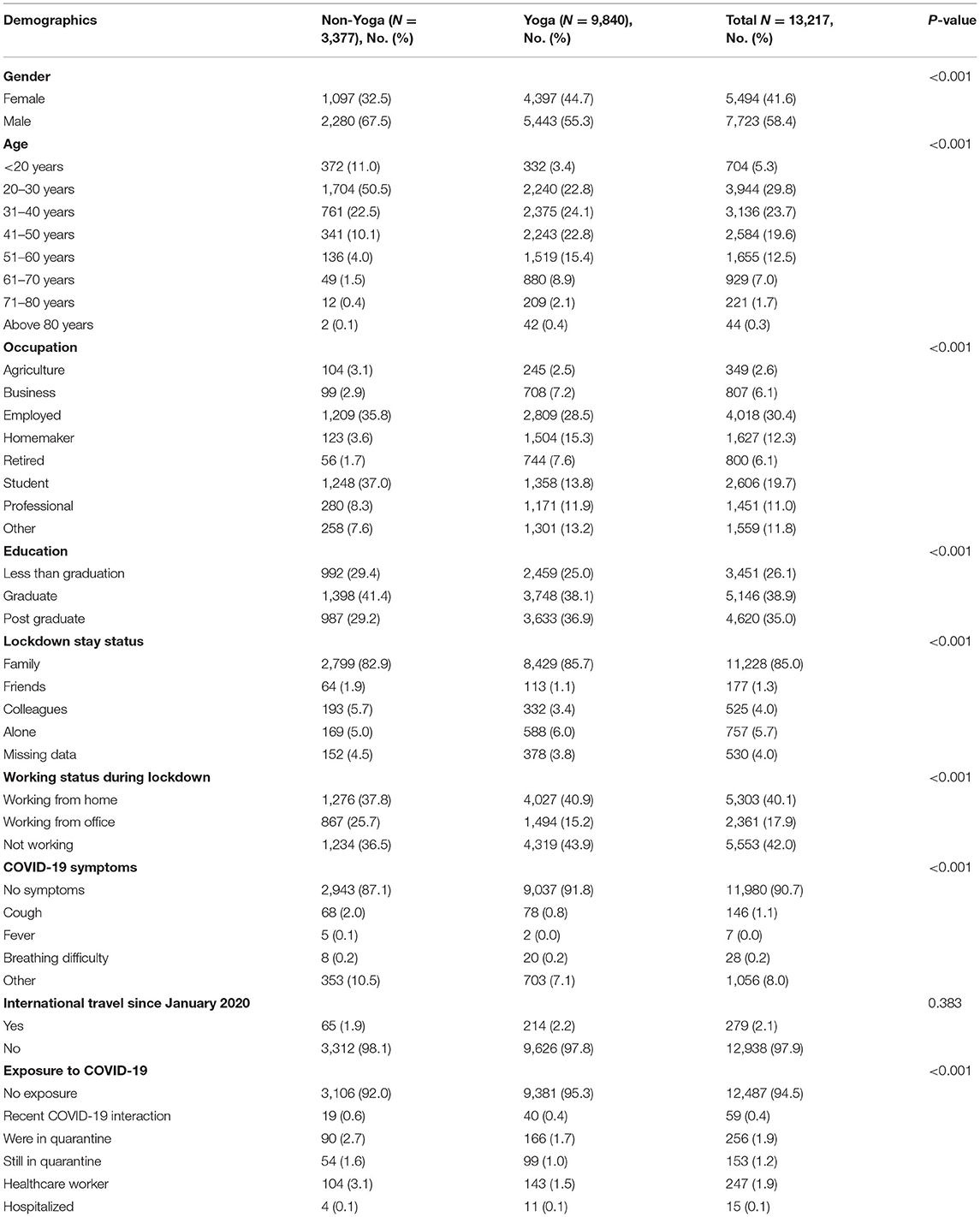

Table 2 summarizes the demographics of the non-Yoga group (25.6%), Yoga group (74.4%), and total participants. Participation of males in the survey was proportionally higher in both non-Yoga (67.5%) and Yoga (55.3%) groups. The young population in the age group of 20–30 years was higher in the non-Yoga (50.5%) group than in the Yoga group (22.8%). The participation from the age group > 50 years was higher in the Yoga group (26.8%) than in the non-Yoga group (6.0%). Our data also revealed that the percentage of employed and professional participants was higher in both groups, with 44.1% in non-Yoga and 40.4% in Yoga. The non-Yoga group had 37.0% participation from young students. Most of the participants had a good educational background as they were either graduates or post-graduates. We noted that 85.0% of the participants stayed with their family during the lockdown, apparently lending help to cope with stress. On further analysis, we found that the non-working participants were fewer in the non-Yoga group (36.5 vs. 43.9%). Furthermore, the proportion of participants going to the office during lockdown was more in the non-Yoga group (25.7 vs. 15.2%).

COVID-19 Exposure

Participants with no symptoms are less likely to be in the non-Yoga group than participants with cough, fever, breathing difficulty, and other symptoms (Table 2). The symptoms of COVID-19 were self-reported. Approximately 98.1% of non-Yoga and 97.8% of the Yoga group did not undertake any international travel since January 2020. Further, the non-Yoga group is more likely to have exposure to COVID-19 than the Yoga group.

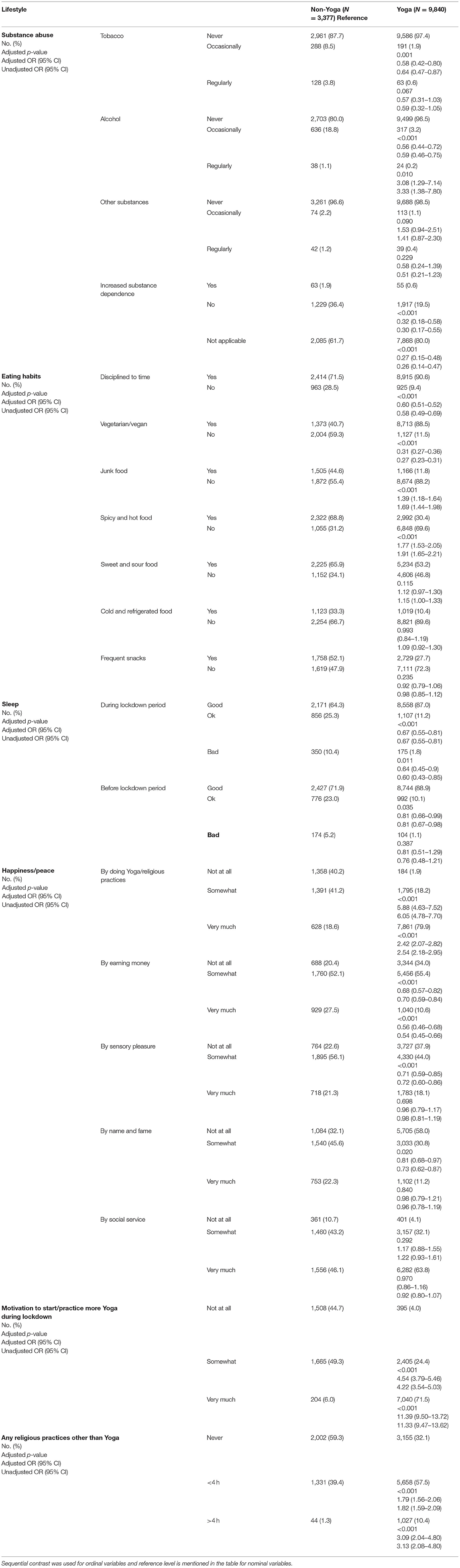

Lifestyle

Although the proportion of participants using substances was lower in both groups, the non-Yoga group was more likely to depend on alcohol, tobacco, and other substances (Table 3). The non-Yoga group was less likely to have a good quality of sleep before and during the lockdown than the Yoga group, odds ratio (OR) <1 (Table 3).

Participants of the non-Yoga group were less likely to have food in a disciplined manner [unadjusted OR = 0.58 (0.49–0.69), adjusted OR = 0.60 (0.51–0.52)] and were less likely to be vegetarian [unadjusted OR = 0.27 (0.23–0.31), adjusted OR = 0.31 (0.27–0.36)] (Table 3). The non-Yoga group was more likely to consume junk food [unadjusted OR = 1.69 (1.44–1.98), adjusted OR = 1.39 (1.18–1.64)] and spicy and hot food [unadjusted OR = 1.91 (1.65–2.21), adjusted OR = 1.77 (1.53–2.05)]. Interestingly, about 55.3% of the non-Yoga participants were motivated to start Yoga during the lockdown (Table 3).

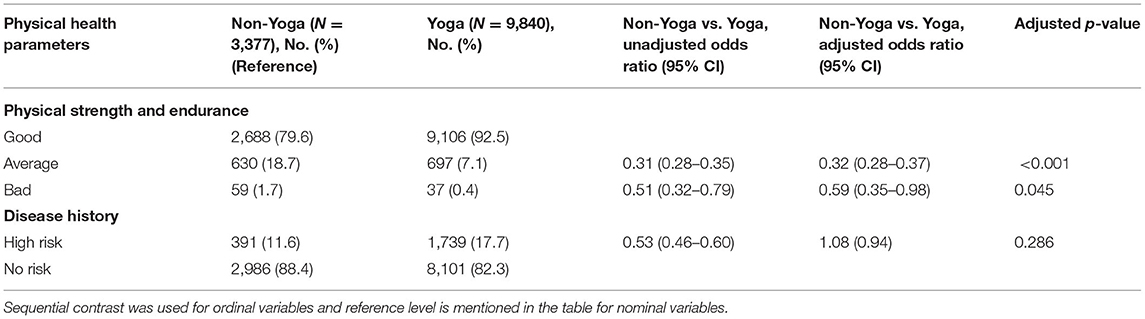

Physical Health

The Yoga group reported very good physical strength and endurance, with only 7.5% of participants reporting an average or below average physical strength and endurance (Table 4). The non-Yoga practitioners were less likely to have good physical strength and endurance (OR < 1), suggesting physical endurance attributes might be superior in Yoga practitioners. Disease risk for co-morbidities, including heart diseases, lung disease, blood pressure, and others, was lower in both the groups (Table 4).

Mental Health

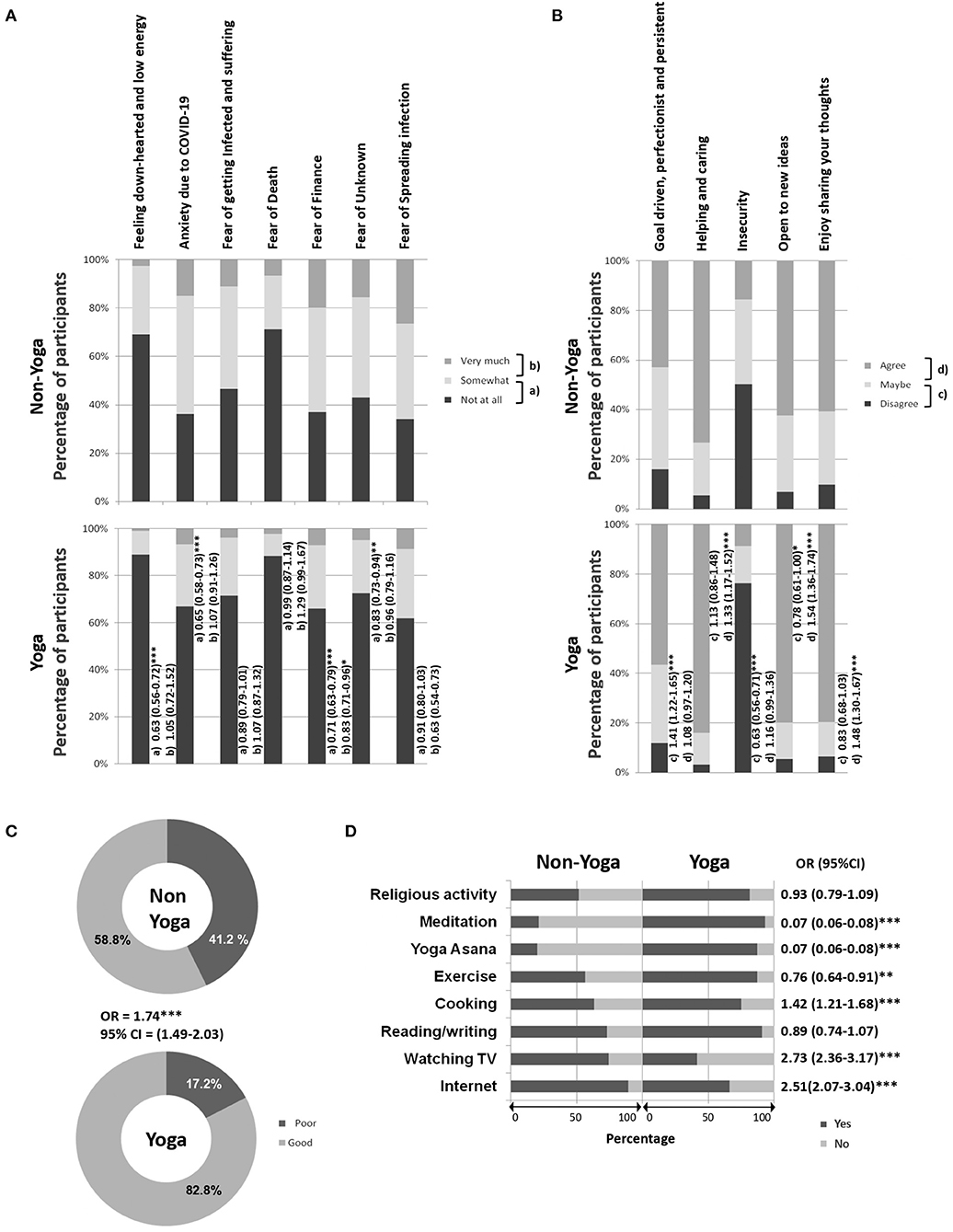

The non-Yoga group reported higher anxiety and fear than the Yoga group when asked about “down-hearted” feeling, low energy (30.9%), anxiety due to COVID-19 (63.9%), fear of getting infected, related suffering (53.4%), fear of death (28.7%), fear of financial difficulties (63.0%), fear of the unknown (57.0%), and fear of spreading infection (65.9%) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Mental health and coping strategy of non-Yoga and Yoga groups. (A) Anxiety and fear during lockdown, (B) general personality, (C) coping ability, and (D) coping activities. In (A,B), odds ratio and CI (in brackets) for each parameter are mentioned on the right side of the bar. The small alphabets represent the pair of tested variables when Yoga group is compared with non-Yoga group. The representation are (a) not at all vs. somewhat, (b) somewhat vs. very much, (c) disagree vs. maybe, and (d) maybe vs. agree. Sequential contrast was used for ordinal variables. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Furthermore, the non-Yoga group was less goal-driven and oriented toward perfection in their activities (15.9%), less helpful and caring (5.2%), more insecure (50.2%), not open to new ideas (6.6%), and do not enjoy sharing their thoughts (9.7%) than the Yoga group (Figure 1B).

Strategies for Coping With COVID-19 and Lockdown-Related Stress

Most of the Yoga group members reported good coping ability (82.8%), while most of the non-Yoga (58.8%) group reported poor coping ability thereby highlighting a significant difference in two groups (Figure 1C).

Figure 1D shows that the non-Yoga group could cope using the Internet, watching TV, reading/writing, cooking, religious activity, and exercise (>50%). In contrast, the Yoga group was engaged in yoga Asanas, meditation, and religious/spiritual activities besides using the Internet, reading/writing, cooking, and exercise (>50%).

Meditation Is Highly Effective to Bring Mental Stability and Strength

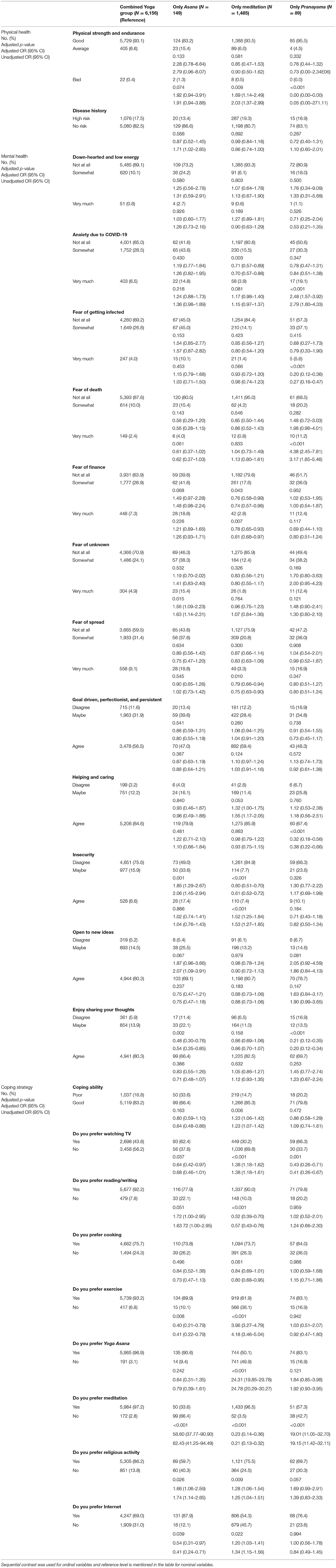

We also examined whether practicing a combination of Asanas, Pranayama, and meditation has a different influence on outcome variables than practicing one of these three yogic practices, individually. Table 5 summarizes the different parameters of physical health, mental health, and coping strategies of four sub-groups. Meditation was frequently performed by the age group of 41–50 years (26.3%), while Asana (49.7%) and Pranayama (39.3%) were favored by young people between the ages of 20 and 30 years. The consolidated Yoga practice was preferred mainly by participants of 31–40 years (24.5%).

Table 5. Physical health, mental health, and coping strategy among the different Yoga groups practicing all or a particular form of Yoga.

Physical health, predicted by strength and endurance, revealed that the Asana group might have lower physical health, whereas co-morbidities were higher in the meditation group (19.3%). Good mental ability was revealed by lower anxiety and stress in the meditation group, followed by the combined group, Asana and Pranayama, sequentially. In addition, the ability to cope with the stress of COVID-19 was highest and comparable in the meditation group (85.3%) and the combined yoga group (83.2%). The preference of watching TV during lockdown was least in the meditation group (30.2%); their preferences included reading/writing (90.0%) and meditation (96.5%). The combined group preferred a range of activities, including reading/writing (92.2%), cooking (75.7%), exercise (93.2%), Yogasana (96.9%), meditation (97.1%), and religious activity (86.2%). TV watching was preferred by the Pranayama group (66.3%) followed by the Asana group (62.4%), and the Internet was preferred by the Asana group (87.9%) followed by the Pranayama group (76.4%). The aforementioned observations suggest that meditation might be more effective in reducing stress and anxiety and improving coping abilities in lockdown situations.

Discussion

Despite limited public health intervention strategies, Yoga has remained the mainstay for improving well-being, disease risk reduction, and improving mental and physical health (17–20, 24, 25). We had earlier reported significant barriers in access to Yoga resources even though the prevalence of Yoga in India and elsewhere was significantly noteworthy (26, 27). Regardless, several studies have reported over time better physical health, mental health, and quality of life both among healthy individuals and those with disease or disorder (17–20, 24, 25). Yoga has been known to improve physical and mental health compared with a physically active group or a physically inactive group, yet the reliance on its anticipated benefits has never been assessed in any nationwide study during a health crisis (28, 29).

Yoga represents a regulated lifestyle that involves Asanas, Pranayamas, and meditation. It makes an individual self-aware of his/her body, mind, thoughts, and soul. The Yogic teaching is based on the fundamentals of Yama (restraints) and Niyama (observances) (30). Yama includes teachings of non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, moderation, and non-hoarding, whereas Niyama includes teachings of cleanliness, contentment, self-discipline, self-study, and wellness. Yoga practitioners routinely isolate themselves from the general population to achieve higher spiritual goals (31). Thus, one who follows the Yoga and Yogic lifestyle can easily maintain cleanliness and social distancing without an agitated mind. Therefore, Yoga practitioners can be hypothesized to quickly adapt to lockdown rules without experiencing chronic anxiety and stress.

The present study extends the above hypothesis operationalized as an investigation carried out when the world is gripped with fear and uncertainty due to an impending pandemic. In this context, the present study has evaluated the outcomes of physical and mental health, including lifestyle and coping strategies of Yoga and non-Yoga groups, during the lockdown imposed by COVID-19 pandemic. A CHAS questionnaire was generated following the Delphi protocol and was circulated among the Indian mass by snowball method as Google Forms. Phone calls and special requests were sent to different sections of the society including ~200 universities, Corporate companies, healthcare institutions, government organizations, wellness centers, and their networks to acquire data. The data were collected between May 9, 2020 and May 31, 2020; data were downloaded daily.

In the present survey, among the total respondents of 23,290, 42.2% (n = 9,840) were Yoga practitioners, which is much higher than the previous report of 11.8% of a nationwide randomized structured survey in 2017 (27). This may not indicate a true rise in the number of yoga practitioners in the country as this was not a randomly selected population.

The current study reports proportionately higher response from males than females. Non-Yoga group has a higher percentage of young participants than the Yoga group, which is a limitation of the study. In both Yoga and non-Yoga groups, most of the participants were employed or well-educated professionals. Furthermore, the analysis of the data collected during this survey revealed that both groups represented a similar proportion of participants living with family; however, a small proportion of participants were also reported to be living alone in both groups. Thus, loneliness cannot be a leading attribute of anxiety, stress, and fear in this study. Another feature of the participants who responded to the survey was that a greater proportion of the working and office going population was represented in the non-Yoga. Working and attending office during the lockdown may be considered as a reason for not practicing Yoga.

Emerging data have shown differences in the susceptibility to COVID-19 symptoms based on age and co-morbidities (4). Studies have shown the benefits of Yoga intervention in reducing the risk and severity of diabetes and other co-morbidities (24, 25). Such interventions may, therefore, be helpful for the risk reduction of COVID-19. Our data show increased non-Yoga group susceptibility to COVID-19 compared with those belonging to the Yoga group; however, RT-PCR for COVID-19 was not carried out to confirm this. Regardless, this calls for new public health and cost-effective intervention strategies based on a digital Yoga interface, compliant to Tele-Yoga regulations. Recently, a breathing technique known as Liuzijue has been reported to improve pulmonary function and quality of life in discharged COVID-19 patients (32). However, it cannot be neglected that the Yoga group is mainly constituted by participants who are “not working” or “working from home,” because of which they have a lower COVID-19 risk and are less fearful about COVID-19.

Sleeping and eating habits in the Yoga group were more health promotive. Furthermore, it also revealed that the dependence on substances use, as resources to cope with anxiety and stress, was lower in the Yoga group. Moreover, good physical strength and endurance coupled with the absence of chronic disease were also proportionately higher in the Yoga group, suggesting better health outcomes corresponding to COVID-19. Our study, however, did not estimate the non-Yoga exercise groups consisting of sportsmen or other physical activities.

We observed that the non-Yoga group was coping with COVID-19 lockdown by relying on the Internet, TV, reading/writing, cooking, and exercise, while the Yoga group was more engaged in Asana, meditation, and religious/spiritual activities besides using the Internet, reading/writing, cooking, and exercise. The Yoga group maintained their routine consistently, while the non-Yoga group could not sustain their regular practices.

The comparisons between the two groups unanimously showed that the non-Yoga group faced mental challenges. They reported higher anxiety and fear associated with COVID-19, including fear of getting infected with COVID-19, death, finance-related stress, and spreading COVID-19 in addition to other unknown causes. Instead, compared with the non-Yoga group, the Yoga group was reportedly more goal-driven and methodical, eliciting responses that showed a helping and caring attitude. The latter group displayed more openness to new ideas and enjoyed sharing their thoughts, being less insecure. Reports from China also show similar psychological distress (8, 17, 33).

COVID-19–related stress creates panic and reduces quality of life in patients as well as in healthcare workers (HCWs). Hence, introducing Yoga in the healthcare system would be beneficial for the patients, HCWs, and other service providers: they may successfully cope with psychological stress (34–37). Stress, anxiety, and depression among HCWs in COVID-19 pandemic was reduced by practicing Sudarshan kriya (38). Perceived stress in COVID-19 patients was also reduced by multimedia psychoeducational intervention, which included relaxation and mindfulness techniques (39). Not limited to COVID-19, integrative medicine including modern medicine, Yoga, mindfulness techniques, Ayurveda, and many more can be helpful for managing health and quality of life, and have the ability to reduce severity of disease. However, randomized trials are required to develop integrative healthcare.

It has been shown that meditation can potentially decrease the risk of acquiring cold and flu by improving physiological function and quality of life (40). Yogic breathing techniques improve respiratory and cardiac function, rendering it an effective tool to combat COVID-19 (41). Yoga will help calm down the mind and enhance immunity (17–20). PTSD due to natural disasters, epidemics, and wars has been shown to regress after practicing Yoga (42). Its application in the current pandemic using the digital module of Yoga and mindfulness may be helpful. If administered to COVID-19 patients under supervision, it may even reduce psychological stress (43). A few randomized controlled trials are taken up in the present pandemic that are investigating the efficacy of various breathing techniques including Yogic breathing in COVID-19 (44–46).

It is pertinent to note that we had stratified the Yoga group into a consolidated Yoga group, only Asana, only Pranayama, and only meditation groups. Meditation seemed to evoke beneficial outcomes than those practicing all, i.e., Asana, Pranayamas, and meditation. However, a longitudinal randomized trial is imperative to establish evidence. Our observation that the younger population preferred Asanas and Pranayama, while meditation was mainly preferred by the elderly, can help deliver innovative yoga protocols that make meditation more attractive to the young population and, consequently, useful for mental hygiene if presented as integrated yoga protocols (available at www.svyasa.edu.in). Our report highlights that a large number of subjects practiced consolidated Yoga (including Asanas, Pranayama, and meditation), proving the acceptability of an integrated module for school and college teachers. This could partly be due to the widespread popularity of both the Common Yoga Protocol released by the Ministry of AYUSH on the eve of International Day of Yoga, celebrated on June 21, as well as the widely published efficacy of Diabetic Yoga Protocol and COVID-19 Yoga Protocols released by the S-VYASA University (47, 48). These protocols include Asana, Pranayama, and meditation.

Limitations of the Study

The study is limited by the fact that the sampling does not generate a study group that represents the general population as it was collected through social media. Second, the duration and regularity of Yoga practice before the lockdown was not assessed in the Yoga group, which would have given details of practice before lockdown. The same was assessed for lockdown period. Third, a proportionately higher number of younger subjects were found represented in the non-Yoga group; this might have influenced the outcome in a few components of the scales like the use of the Internet, physical strength, and others. Fourth, the self-reported COVID-19 symptoms could not be verified and RT-PCR for COVID-19 was not performed to establish increased susceptibility of non-Yoga group because of the lockdown restrictions. Fifth, a non-standard questionnaire was used. Mental health was not evaluated by any neuropsychological questionnaire such as the Perceived Stress Scale, but was based on the responses of CHAS.

We also could not rule out the role of physical exercises in improving mental and physical health; however, outdoor activities were restricted due to the lockdown. Furthermore, whether the restrictions mentioned earlier provided the environment conducive for the practice of Asanas, Pranayamas, and meditation, available through digital media, cannot be ascertained unless another validation study is carried out. In addition, we did not explore means to rule out repetitive form filling by the same individual due to error or intention; however, there were no rewards or benefits attached to completing the survey. Because the survey was administered online, the possibility of cognitive bias in the study was minimal; however, we entirely relied on the answers provided online without verifying the IP address, consistent with similar reports published elsewhere.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon eligible request.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

RN conceptualized the study, supervised data collection, and involved in discussions during article preparation. AA conceptualized the article. MR and MSS wrote and edited the article and contributed in data presentation. MNKS conceptualized the study. RK and JI performed the statistical analyses. AS created the scale and administered it nationally. HN envisioned the study, and inspired and guided the study to its completion imparting quality assurance. RN, AA, and VS critically reviewed and edited the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the participants of the CHAS survey. This study is part of a larger pan-India study.

Abbreviations

CHAS, COVID Health Assessment Scale; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; OR, Odds ratio; PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorders; S-VYASA, Swami Vivekananda Yoga AnusandhanaSamsthana.

References

1. The Lancet. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. (2020) 395:1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30938-7

2. Liu MY, Li N, Li WA, Khan H. Association between psychosocial stress and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Res. (2017) 39:573–80. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2017.1317904

3. Mishra A, Podder V, Modgil S, Khosla R, Anand A, Nagarathna R, et al. Perceived stress and depression in prediabetes and diabetes in an Indian population-A call for a mindfulness-based intervention. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2020) 64:127–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.01.001

4. Wang B, Li R, Lu Z, Huang Y. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: evidence from meta-analysis. Aging. (2020) 12:6049–57. doi: 10.18632/aging.103000

5. Orso D, Federici N, Copetti R, Vetrugno L, Bove T. Infodemic and the spread of fake news in the COVID-19-era. Eur J Emerg Med. (2020) 27:327–8. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000713

6. Garfin DR, Silver RC, Holman EA. The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychol. (2020) 39:355–7. doi: 10.1037/hea0000875

7. Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, Fan B, Fang Y, Kong J, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. (2012) 53:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003

8. Main A, Zhou Q, Ma Y, Luecken LJ, Liu X. Relations of SARS-related stressors and coping to Chinese college students' psychological adjustment during the 2003 Beijing SARS epidemic. J Couns Psychol. (2011) 58:410–23. doi: 10.1037/a0023632

9. Farooqui M, Quadri SA, Suriya SS, Khan MA, Ovais M, Sohail Z, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder: a serious post-earthquake complication. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. (2017) 39:135–43. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0029

10. Restauri N, Sheridan AD. Burnout and posttraumatic stress disorder in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: intersection, impact, and interventions. J Am Coll Radiol. (2020) 17:921–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.021

11. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

12. Liu X, Luo WT, Li Y, Li CN, Hong ZS, Chen HL, et al. Psychological status and behavior changes of the public during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Infect Dis Poverty. (2020) 9:58. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00678-3

13. Hamer M, Kivimäki M, Gale CR, Batty GD. Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: a community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:184–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.059

14. Pietrobelli A, Pecoraro L, Ferruzzi A, Heo M, Faith M, Zoller T, et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: a longitudinal study. Obesity. (2020) 28:1382–5. doi: 10.1002/oby.22861

15. Varshney M, Parel JT, Raizada N, Sarin SK. Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian Community: an online (FEEL-COVID) survey. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0233874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233874

16. Rehman U, Shahnawaz MG, Khan NH, Kharshiing KD, Khursheed M, Gupta K, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among Indians in times of Covid-19 lockdown. Community Ment Health J. (2020) 23:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00664-x

17. Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Ski CF. Yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and stress-related physiological measures: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2017) 86:152–68. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.08.008

18. Hendriks T. The effects of Sahaja Yoga meditation on mental health: a systematic review. J Complement Integr Med. (2018) 15:20160163. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2016-0163

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, Houts CR, Malarkey WB, Emery CF, et al. Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice. Psychosom Med. (2010) 72:113–21. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb9377

20. Joseph B, Nair PM, Nanda A. Effects of naturopathy and yoga intervention on CD4 count of the individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy-report from a human immunodeficiency virus sanatorium, Pune. Int J Yoga. (2015) 8:122–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.158475

21. George N, Barrett N, McPeake L, Goett R, Anderson K, Baird J. Content validation of a novel screening tool to identify emergency department patients with significant palliative care needs. Acad Emerg Med. (2015) 22:823–37. doi: 10.1111/acem.12710

22. Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. (2003) 41:376–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x

23. Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e20476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476

24. Bali P, Kaur N, Tiwari A, Bammidi S, Podder V, Devi C, et al. Effectiveness of Yoga as the public health intervention module in the management of diabetes and diabetes associated dementia in South East Asia: a narrative review. Neuroepidemiology. (2020) 54:287–303. doi: 10.1159/000505816

25. Park SH, Han KS. Blood pressure response to meditation and Yoga: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. (2017) 23:685–95. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0234

26. Mishra A, Chawathey SA, Mehra P, Nagarathna R, Anand A, Rajesh SK, et al. Perceptions of benefits and barriers to Yoga practice across rural and urban India: Implications for workplace Yoga. Work. (2020) 65:721–32. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203126

27. Mishra AS, Sk R, Hs V, Nagarathna R, Anand A, Bhutani H, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of Yoga in rural and urban India, KAPY 2017: a nationwide cluster sample survey. Medicines. (2020) 7:8. doi: 10.3390/medicines7020008

28. Govindaraj R, Karmani S, Varambally S, Gangadhar BN. Yoga and physical exercise - a review and comparison. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2016) 28:242–53. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2016.1160878

29. Sivaramakrishnan D, Fitzsimons C, Kelly P, Ludwig K, Mutrie N, Saunders DH, et al. The effects of yoga compared to active and inactive controls on physical function and health related quality of life in older adults- systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2019) 16:33. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0789-2

30. Saraswati S, Saraswati SN. Four Chapters on Freedom: Commentary on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Munger: Yoga Publications Trust (2002).

31. Muktibodhananda S. Hatha Yoga Pradipika. 4th ed. Munger, Bihar: Yoga Publications Trust (2012). p. 718.

32. Tang Y, Jiang J, Shen P, Li M, You H, Liu C, et al. Liuzijue is a promising exercise option for rehabilitating discharged COVID-19 patients. Medicine. (2021) 100:e24564. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024564

33. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. (2020) 33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

34. Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:510–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017

35. Ornell F, Halpern SC, Kessler FHP, Narvaez JCM. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. Cad Saude Publica. (2020) 36:e00063520. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00063520

36. Sadhasivam S, Alankar S, Maturi R, Vishnubhotla RV, Mudigonda M, Pawale D, et al. Inner engineering practices and advanced 4-day Isha Yoga retreat are associated with cannabimimetic effects with increased endocannabinoids and short-term and sustained improvement in mental health: a prospective observational study of meditators. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2020) 2020:8438272. doi: 10.1155/2020/8438272

37. La Torre G, Raffone A, Peruzzo M, Calabrese L, Cocchiara RA, D'Egidio V, et al. Yoga and mindfulness as a tool for influencing affectivity, anxiety, mental health, and stress among healthcare workers: results of a single-arm clinical trial. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:1037. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041037

38. Divya K, Bharathi S, Somya R, Darshan MH. Impact of a Yogic breathing technique on the well-being of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob Adv Health Med. (2021) 10:2164956120982956. doi: 10.1177/2164956120982956

39. Shaygan M, Yazdani Z, Valibeygi A. The effect of online multimedia psychoeducational interventions on the resilience and perceived stress of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a pilot cluster randomized parallel-controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:93. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03085-6

40. Obasi CN, Brown R, Ewers T, Barlow S, Gassman M, Zgierska A, et al. Advantage of meditation over exercise in reducing cold and flu illness is related to improved function and quality of life. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. (2013) 7:938–44. doi: 10.1111/irv.12053

41. Santaella DF, Devesa CR, Rojo MR, Amato MB, Drager LF, Casali KR, et al. Yoga respiratory training improves respiratory function and cardiac sympathovagal balance in elderly subjects: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. (2011) 1:e000085. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000085

42. Gallegos AM, Crean HF, Pigeon WR, Heffner KL. Meditation and yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 58:115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.004

43. Wei N, Huang BC, Lu SJ, Hu JB, Zhou XY, Hu CC, et al. Efficacy of internet-based integrated intervention on depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with COVID-19. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. (2020) 21:400–4. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2010013

44. Lai KSP, Watt C, Ionson E, Baruss I, Forchuk C, Sukhera J, et al. Breath regulation and yogic exercise an online therapy for calm and happiness (BREATH) for frontline hospital and long-term care home staff managing the COVID-19 pandemic: a structured summary of a study protocol for a feasibility study for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. (2020) 21:1–3. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04583-w

45. Weiner L, Berna F, Nourry N, Severac F, Vidailhet P, Mengin AC. Efficacy of an online cognitive behavioral therapy program developed for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the REduction of STress (REST) study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. (2020) 21:870. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04772-7

46. Zhang S, Zhu Q, Zhan C, Cheng W, Mingfang X, Fang M, et al. Acupressure therapy and Liu Zi Jue Qigong for pulmonary function and quality of life in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19): a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. (2020) 21:751. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04693-5

47. Common Yoga Protocol. Ministry of AYUSH (2020). Available online at: http://mea.gov.in/images/pdf/common-yoga-protocol-english.pdf (accessed August 8, 2020).

Keywords: COVID-19, Yoga, global health, stress, coping straregies

Citation: Nagarathna R, Anand A, Rain M, Srivastava V, Sivapuram MS, Kulkarni R, Ilavarasu J, Sharma MNK, Singh A and Nagendra HR (2021) Yoga Practice Is Beneficial for Maintaining Healthy Lifestyle and Endurance Under Restrictions and Stress Imposed by Lockdown During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 12:613762. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.613762

Received: 07 October 2020; Accepted: 11 May 2021;

Published: 22 June 2021.

Edited by:

Rochelle Eime, Victoria University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Lucia Sideli, Libera Università Maria SS. Assunta, ItalyRamajayam Govindaraj, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, India

Copyright © 2021 Nagarathna, Anand, Rain, Srivastava, Sivapuram, Kulkarni, Ilavarasu, Sharma, Singh and Nagendra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Raghuram Nagarathna, cm5hZ2FyYXRuYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Akshay Anand, YWtzaGF5MWFuYW5kQHJlZGlmZm1haWwuY29t

Raghuram Nagarathna

Raghuram Nagarathna Akshay Anand

Akshay Anand Manjari Rain

Manjari Rain Vinod Srivastava

Vinod Srivastava Madhava Sai Sivapuram

Madhava Sai Sivapuram Ravi Kulkarni

Ravi Kulkarni Judu Ilavarasu

Judu Ilavarasu Manjunath N. K. Sharma

Manjunath N. K. Sharma Amit Singh

Amit Singh Hongasandra Ramarao Nagendra

Hongasandra Ramarao Nagendra