- 1Institute of Mental Health, Hebei Mental Health Centre, Baoding, China

- 2Unit of Psychiatry, Department of Public Health and Medicinal Administration, Faculty of Health Sciences and Institute of Translational Medicine, University of Macau, Macao, China

- 3Centre for Cognitive and Brain Science, University of Macau, Macao, China

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Chaohu Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

- 5Anhui Psychiatric Center of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

- 6The National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders and Beijing Key Laboratory of Mental Disorders, Beijing Anding Hospital and the Advanced Innovation Center for Human Brain Protection, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 7The Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou Huiai Hospital), Guangzhou, China

- 8Beijing Municipal Key Laboratory of Clinical Epidemiology, Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 9The University of Notre Dame Australia, Fremantle, WA, Australia

- 10Division of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA, Australia

- 11Department of Psychiatry, The Melbourne Clinic and St. Vincent's Hospital, University of Melbourne, Richmond, VIC, Australia

Background: Constipation is a common but often ignored side effect of antipsychotic treatment, although it is associated with adverse outcomes. The results of the efficacy and safety of traditional Chinese herbal medicine (TCM) in treating constipation are mixed across studies. This is a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of the efficacy and safety of TCM compared to Western medicine (WM) in treating antipsychotic-related constipation.

Methods: Major international electronic (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science) and Chinese (Wanfang, WeiPu VIP, SinoMed, and CNKI) databases were searched from their inception to November 29, 2020. Meta-analysis was performed using the random-effects model.

Results: Thirty RCTs with 52 arms covering 2,570 patients in the TCM group and 2,511 patients in the WM group were included. Compared with WM, TCM alone was superior regarding the moderate response rate [risk ratio (RR) = 1.165; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.096–1.238; P < 0.001], marked response rate (RR = 1.437; 95% CI: 1.267–1.692; P < 0.001), and remission rate (RR = 1.376; 95% CI: 1.180–1.606; P < 0.001) for constipation, while it was significantly associated with lower risk of rash (RR = 0.081; 95% CI: 0.019–0.342; P = 0.001). For the moderate response rate, meta-regression analyses revealed that publication year (β = −0.007, P = 0.0007) and Jadad score (β = 0.067, P < 0.001) significantly moderated the results. For the remission rate, subgroup and meta-regression analyses revealed that the geographical region (P = 0.003), inpatient status (P = 0.035), and trial duration (β = 0.009, P = 0.013) significantly moderated the results.

Conclusions: The efficacy of TCM for antipsychotic-related constipation appeared to be greater compared to WM, while certain side effects of TCM, such as rash, were less frequent.

Introduction

Constipation is a common side effect of antipsychotics with a prevalence rate between 28.1 and 36.3% (1–3) and is associated with a range of severe consequences, such as paralytic ileus, bowel ischemia, sepsis, intestinal perforation, and even pre-mature mortality (4, 5). The occurrence of constipation in psychiatric patients may be associated with a decrease in gastrointestinal hypomotility due to peripheral muscarinic anticholinergic activity (6, 7). For instance, certain antipsychotics, such as clozapine, quetiapine, and olanzapine (8), have strong affinity to muscarinic cholinergic receptors, which could increase peripheral muscarinic anticholinergic activity (9, 10) and may result in constipation.

Commonly used Western medicine (WM) for constipation, including fiber supplements and laxatives, could cause side effects including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and even severe adverse events in certain special populations such as those with renal insufficiency (11, 12). Traditional Chinese herbal medicine (TCM) is commonly prescribed in treating and preventing constipation in clinical practice, particularly in Asian countries such as China (13–15), with good evidence found in some high-quality studies (16–20).

To date, findings on the efficacy and safety of TCM for antipsychotic-related constipation compared with WM have been inconsistent. Recent reviews (21, 22) summarized the efficacy of TCM for antipsychotic-related constipation but only included publications in English databases, even though most relevant studies were only published in Chinese language journals. Consequently, only two studies conducted in China were included; one study (23) focused on physical therapy of traditional Chinese Medicine (e.g., acupuncture and Tuina) and the other focused on the use of 250 ml of 10% mannitol with 2 g of Rhubarb-soda plus 0.8 g of Phenolphthalein Tablets (24). This gave us the impetus to conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of the efficacy and safety TCM and WM in treating antipsychotic-related constipation.

Materials and Methods

This meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020168832) and was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Eligibility Criteria and Outcome Measures

According to the PICOS acronym (25), the inclusion criteria were as follows: Participants (P): patients with constipation caused by antipsychotic medications. Intervention (I): TCM alone. Comparison (C): WM alone or concurrent use of two or more WMs. Outcomes (O): efficacy and safety of TCM. Study design (S): RCTs. Exclusion criteria included (a) severe physical comorbidities and (b) receiving physiotherapy alone or a combination of physiotherapy plus TCM for constipation. Primary outcome included three efficacy measures: moderate response rate, marked response rate, and remission rate. Secondary outcomes included treatment adherence and adverse drug reactions (ADRs), such as nausea, vomiting, and rash.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

Literature search in both international (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science) and Chinese (Wanfang, WeiPu VIP, SinoMed, and CNKI) databases from inception to October 30, 2019, were independently conducted by two researchers (WWR and JJY), using both subject and free terms of the following search terms: “Constipation [MeSH],” “Medicine, Chinese Traditional [MeSH],” and “Randomized Controlled Trial [MeSH]” (Supplementary Table 2). An updated search to November 29, 2020, was also performed.

The same two researchers (WWR and JJY) independently screened titles and abstracts and then read full texts of relevant publications for eligibility. Any discrepancy was discussed with a third researcher (ZW). In addition, the reference lists of relevant reviews and previous meta-analysis (21, 22) were searched manually for additional studies.

Data Extraction

A pre-designed Excel data collection sheet was used to independently extract relevant data by two researchers (WWR and JJY). The following study and participant characteristics were extracted: the first author, year of publication and survey, sample size, type of medications, mean age of participants, proportion of males, and diagnostic criteria of psychiatric disorders and constipation. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Quality Assessment and Evidence Level

The two researchers (WWR and JJY) independently assessed study quality using both the Jadad scale (0–5 points) (26) and Cochrane risk of bias tool (27). Studies with a Jadad total score of 3 or higher were considered as “high quality;” otherwise, they were considered as “low quality.” The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology was used to evaluate evidence level of primary and secondary outcomes (i.e., very low, low, moderate, or high) (28).

Statistical Analyses

Due to different sample sizes, types and doses of antipsychotic medications, and demographic characteristics between studies, the random-effects model was used to synthesize outcome data, with risk ratio (RRs) and its 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as the effect size. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran's Q and I2 statistic. I2-values of ≥50% and P-value of ≤ 0.10 indicated great heterogeneity across studies. Publication bias was tested using forest plots, Egger's regression test, Begg's rank test, and Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill analysis. The sources of heterogeneity between studies on primary outcomes (e.g., moderate/marked response and remission rates of constipation) were examined by subgroup analyses for categorical variables [e.g., diagnostic criteria for psychiatry: Chinese Mental Disorder Classification and Diagnosis, Third Edition (CCMD-3) vs. Chinese Mental Disorder Classification and Diagnosis, Second Edition (CCMD-2)/Chinese Mental Disorder Classification and Diagnosis, Second Edition, Revised (CCMD-2-R) vs. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), geographic region (east vs. middle vs. west), analysis method (intent to treat vs. per-protocol), and inpatient group (Yes vs. Mix)] and meta-regression analyses for continuous variables (e.g., publication year, trial duration, Jadad total score, and overall sample size). Sensitivity analysis was carried out to identify outlying studies. All statistical analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis (version 2.0; Biostat), with a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Literature Search and Study Characteristics

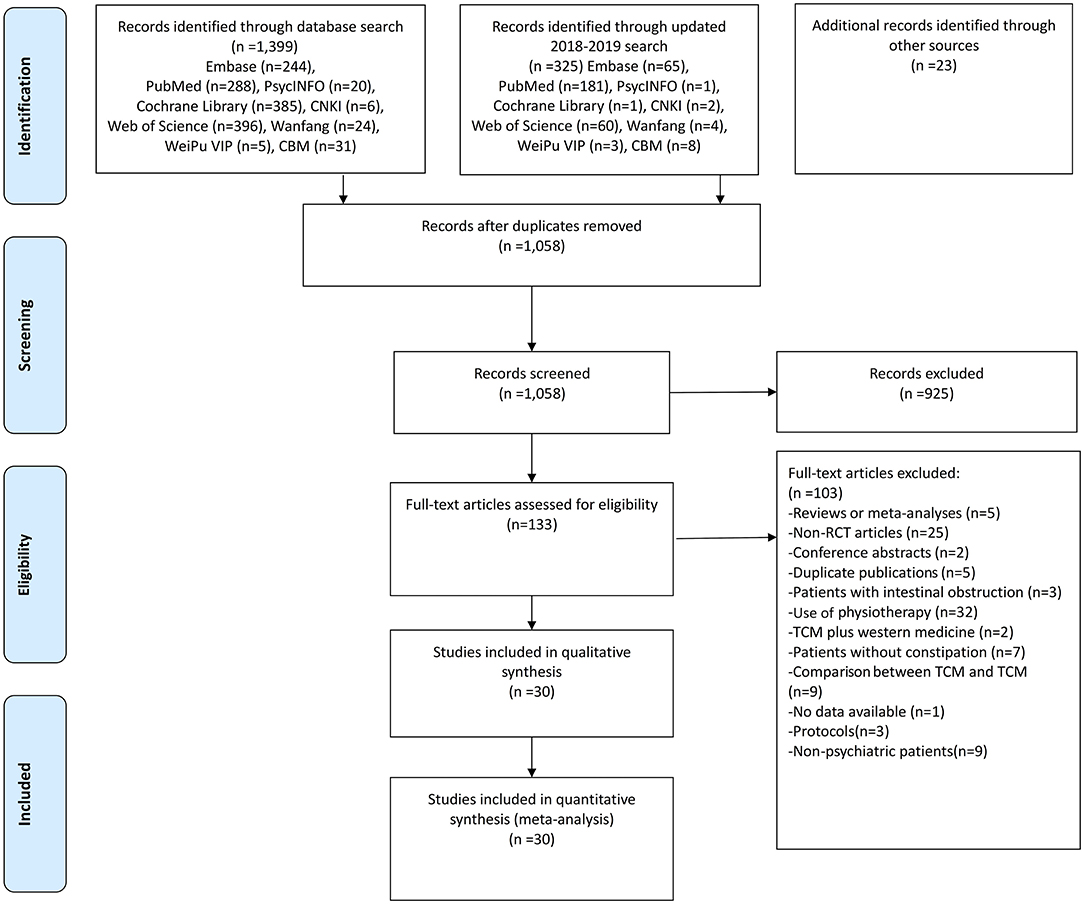

A total of 1,725 articles were initially identified. After screening the titles and abstracts, 133 articles were retrieved for full-text review. Finally, 30 studies with 52 arms (2,570 patients in the TCM group and 2,511 patients in the WM group) were included for meta-analyses (Figure 1).

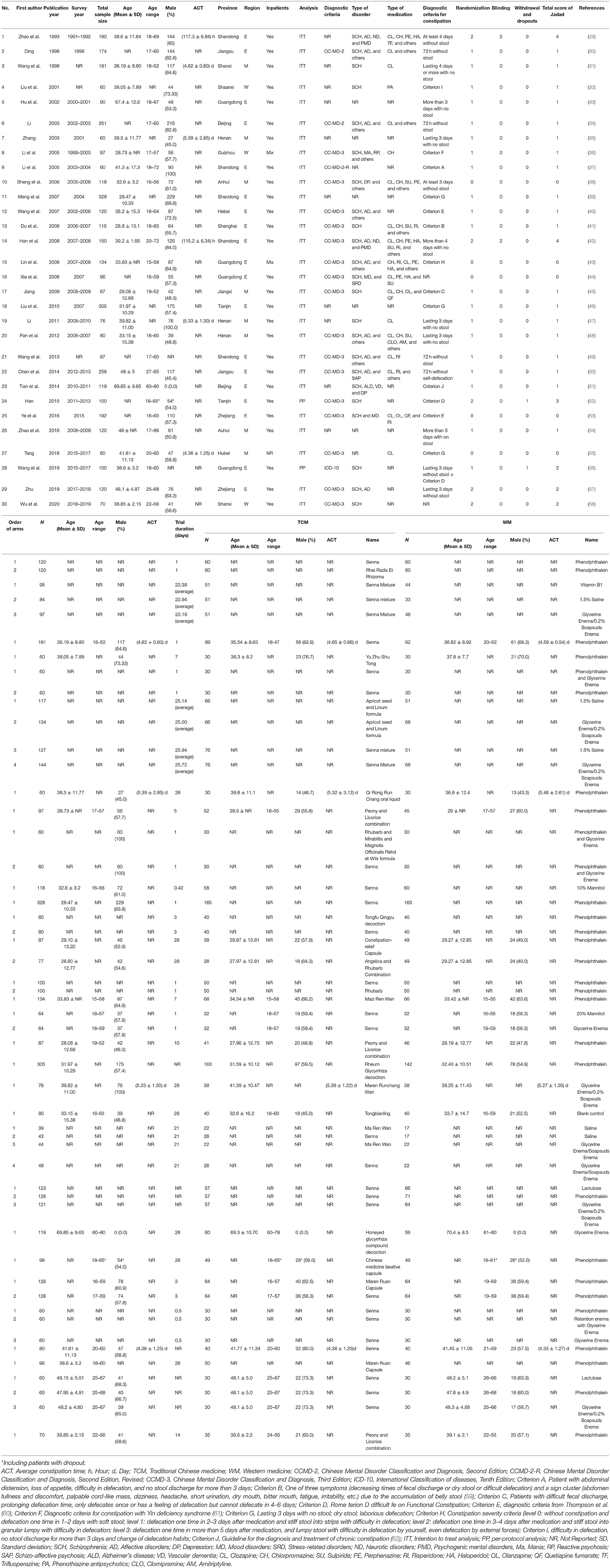

Included studies were published from 1993 to 2020. All studies were conducted in China: 19 studies were conducted in the eastern region, 8 in the central region, and 3 in the western region of China. Sixteen studies used the CCMD-3; two used the CCMD-2; one used the CCMD-2-R; one used the ICD-10; and ten studies did not report diagnostic criteria. The sample size ranged from 60 to 328, and mean age ranged between 28.08 and 69.85 years. Study duration ranged from 0.42 to 28 days (Table 1).

Assessment Quality and Outcome Evidence

The mean Jadad scores of the 30 studies ranged from 0 to 4 with a median of 1; of them, 3 were considered as “high quality” (Table 1). Non-blinded assessment and omission of reported dropout were the major reasons for low quality. For the assessment of Cochrane risk of bias, five RCTs mentioned “randomization” in detail (i.e., low risk), and five RCTs used randomization with incorrect methods (i.e., high risk). In addition, no RCT described allocation concealment; therefore, the biases were unclear. Two RCTs mentioned “blinding” (Supplementary Figure 1). The overall quality of the 13 meta-analyzable outcomes was rated as “moderate” (15.4%, 2/13) and “high” (3.03%, 1/13) according to the GRADE approach (Supplementary Table 1).

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Response Rate

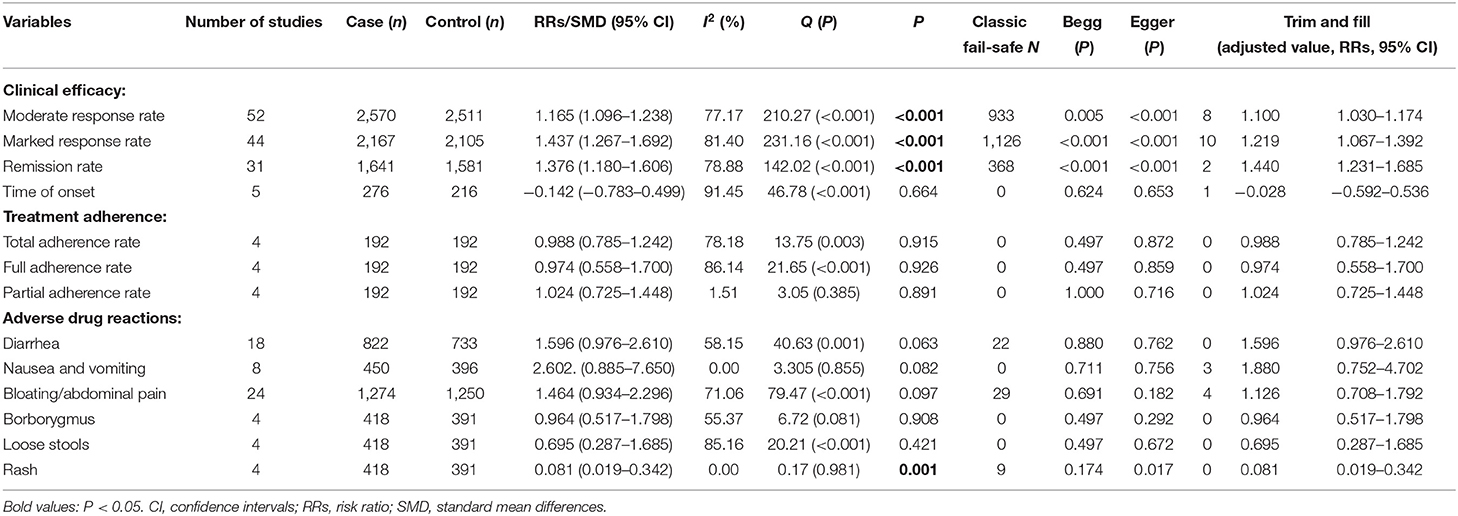

Traditional Chinese herbal medicine alone had significant advantages in terms of the moderate response rate (RR = 1.165; 95% CI: 1.096–1.238, P < 0.001, I2 = 77.17%, Table 2, Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3), marked response rate (RR = 1.437; 95% CI: 1.267–1.692, P < 0.001, I2 = 81.40%, Table 2, Supplementary Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3), and remission rate (RR = 1.376; 95% CI: 1.180–1.606, P < 0.001, I2 = 78.88, Table 2, Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 3) compared to WM. In contrast, no significant difference was found regarding the onset of response after treatment between TCM alone and WM groups (SMD = −0.142; 95% CI: −0.783–0.499; P = 0.664; I2 = 91.45, Table 2).

Treatment Adherence

No difference was found between TCM alone and WM groups in both overall adherence, full adherence, and partial adherence rates (all P-values > 0.05; Table 2).

Adverse Drug Reactions

No group differences were found in most of the ADRs (e.g., diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, bloating/abdominal pain, borborygmus, and loose stools) (all P-values > 0.05; Table 2), while rash was less frequent (RR = 0.081, 95% CI: 0.019–0.342; P = 0.001; I2 = 0.0) in the TCM alone group compared to the WM group (Table 2).

Three RCTs compared relapse or exacerbation rates of constipation after discontinuation and all studies found that those receiving WM has a higher relapse rate than those receiving TCM. Specifically, one RCT found that the TCM group had a significantly lower relapse rate than the WM group at 1, 3, and 6 months after discontinuation (36). Another RCT had a similar finding (TCM: 13.24% vs. WM:36.37%; X2 = 8.45, P < 0.01) at 1 month after discontinuation (43). Jiang et al. (45) reported that some participants had relapsed after discontinuation in the WM group, but the result in the TCM group was not reported.

Subgroup and Meta-Regression Analyses

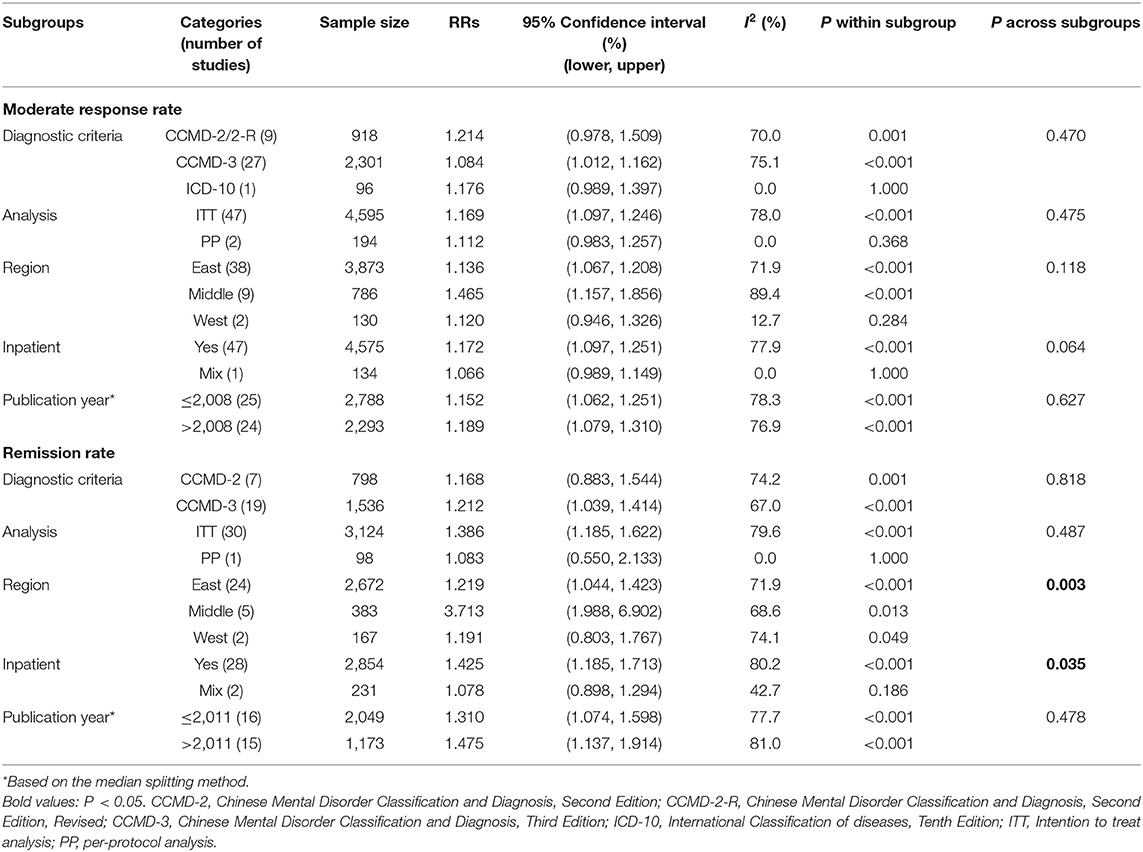

For the moderate response rate, subgroup and meta-regression analyses found that diagnostic criteria of psychiatric disorders (CCMD-2/CCMD-2-R vs. CCMD-3 vs. ICD-10), geographical region (east vs. middle vs. west), analysis method (intent to treat vs. per-protocol), inpatient group (Yes vs. Mix), trial duration (β = −0.002, P = 0.128, n = 44 arms), total sample size (β = −0.0002, P = 0.473), and sample size in the TCM group (β = 0.0004, P = 0.315) and WM group (β = 0.0002, P = 0.717) did not moderate the primary results (all P-values > 0.05, Table 3), except for the publication year (β = −0.007, P = 0.0007) and Jadad score (β = 0.067, P < 0.001).

Table 3. Subgroup analyses of response rate and remission of traditional Chinese medicine compared with Western medicine for constipation.

For the remission rate, subgroup analyses revealed that geographical region (P = 0.003) and inpatient group (P = 0.035) were significantly associated with the results (Table 3). Meta-regression analyses did not reveal significant moderating effects of the publication year (β = 0.009, P = 0.110), Jadad score (β = −0.036, P = 0.624), total sample size (β = 0.0007, P = 0.337), and sample size in the TCM (β = 0.001, P = 0.469) and WM groups (β = 0.002, P = 0.248) on the results, except for the trial duration (β = 0.009, P = 0.013, n = 23 arms).

Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

After excluding one outlying study (37) with two arms in which two WMs were used, the primary results did not significantly change (moderate response rate: RR = 1.156, 95% CI: 1.087–1.230, P < 0.001, I2 = 77.47%; marked response rate: RR = 1.391, 95% CI: 1.229–1.575, P < 0.001, I2 = 80.96%). In addition, we excluded each study one by one, and no significant changes were found in the moderate response rate, marked response rate, or remission rate (Supplementary Figures 8–10).

Both Egger's and Begg's-tests (all P-values > 0.05) and funnel plot did not detect publication bias in most outcomes, but publication bias was found in moderate response rate (Egger's-test: t = 4.248, P < 0.001; Begg's-test: Z = 2.793, P = 0.005; Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 5), marked response rate (Begg's-test: Z = 4.379, P <0.001; Egger's-test: t = 5.790, P < 0.001; Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 6), remission rate (Begg's-test: Z = 3.384, P <0.001; Egger's-test: t = 3.855, P < 0.001; Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 7), and rash (Egger's test, P = 0.017, Table 2). Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill analysis did not find any missing study, which indicates that no missing effect size qualitatively influence the primary results in all outcomes, except for the moderate response rate (missing studies = 8; new RR = 1.1, 95% CI: 1.030–1.174), marked response rate (missing studies = 10; new RR = 1.219, 95% CI: 1.067–1.392), remission rate (missing studies = 2; new RR = 1.440, 95% CI: 1.231–1.685), time of onset (missing studies = 1; new SMD = −0.028, 95% CI: −0.592–0.536), nausea and vomiting (missing studies = 3; new RR = 1.880, 95% CI: 0.752–4.702), and bloating/abdominal (missing studies = 4; new RR = 1.126, 95% CI: 0.708–1.792).

Discussion

This was the first systematic review and meta-analysis that examined the efficacy and safety of TCM in treating antipsychotic-related constipation. Commonly prescribed TCM included Senna, Apricot Seed and Linum Formula, Ma Ren Wan, etc., while WM included Phenolphthalein, Glycerine Enema, etc. We found that TCM alone was superior to WM in terms of moderate response rate, marked response rate, and remission rate for constipation, while TCM alone was significantly associated with lower risk of rash. Skin rash is a common side effect associated with certain Western drug allergy (63) including antipsychotic drugs (64–66). In this meta-analysis compared to WM, TCM has a lower risk of rash. Traditional Chinese herbal medicine has been widely prescribed in China in treating antipsychotic drug-induced constipation (67), and TCM prescriptions strictly follow relevant treatment guidelines and regulations (68).

Our efficacy findings are similar to the findings of large case–control studies (69). An earlier review found that TCM was more effective than cisapride (RR = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.17–0.34), polyethylene glycol (RR = 0.14, 95% CI: 0.06–0.34), mosapride (RR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.23–0.46), and phenolphthalein (RR = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.13–0.46) in treating functional constipation (13), which is consistent with the findings of this study and another meta-analysis (70). Traditional Chinese herbal medicine appears more effective for constipation than WM; however, due to the variety of components found across TCM, the mechanisms are still not clear. To date, no basic science research on the efficacy of TCM for constipation have been published.

Subgroup analyses revealed that the remission rate for treating constipation was moderated by geographical regions. When comparing TCM with WM, the RR of TCM vs. WM was 1.219 (95% CI: 1.044–1.423) in the eastern region and 3.713 (95% CI: 1.988–6.902) in the central region, while no difference was found in the western region of China. It should be noted that most studies were conducted in the eastern region, and only two studies with small sample size were conducted in the western region of China; therefore, the results of this subgroup analysis may not be stable. The different dietary habits among populations between regions in China may be partly responsible for the discrepancy. For example, many people in the central region of China (e.g., Hunan, Hubei, and Jianxi provinces) prefer spicy foods, which could increase the risk of constipation (71), while those in the eastern region prefer bland foods. The advantage of TCM in terms of remission rate was more obvious in the inpatient group compared to the mixed inpatient and outpatient group, which may be related to better treatment adherence among inpatients (72, 73) or due to a small number of studies on mixed patient sample (n = 2). As expected, meta-regression analysis found that a longer trial duration (β = 0.009, P = 0.013) was associated with a higher remission rate of constipation, probably because the delivery of TCM is more stable in longer studies. Meta-regression demonstrated that the moderate response rate was negatively related to the publication year (β = −0.007, P = 0.0007). We speculate that first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) were widely used in the past, which often led to severe constipation (1). In the past decade, however, FGAs have been gradually replaced by second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). In contrast, SGAs are less likely to cause severe constipation (74, 75). Unexpectedly, compared to those with only mild constipation, patients with severe constipation were often more likely to respond to TCM. We speculate that the doses of TCM and types of constipation may moderate this association although relevant data were insufficient to clarify this finding, which needs to be confirmed in future studies. The association of the higher response rate with higher-quality studies might be due to the fact that response is more likely to be identified in higher-quality studies, e.g., those with well-trained researchers and sensitive assessment tools.

The strengths of this systematic review and meta-analysis included the inclusion of both international and Chinese databases, large number of included studies, large sample size, and use of sophisticated analyses (e.g., subgroup, meta-regression, and sensitivity analyses). Some methodological limitations should be noted. First, all studies were conducted in China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other parts of the world. Additionally, the included studies were not large-scale RCTs. Second, the active ingredients of TCM and their optimal doses for constipation were not analyzed due to insufficient data. Unlike WM, due to the varied ingredients in most TCM, no dosages were provided as they were only administered as tablets and/or capsules in clinical practice. Also, due to different components and forms of TCM between included RCTs, head-to-head comparisons of TCM could not be conducted in this meta-analysis. Third, some factors related to constipation, such as lifestyle, outdoor activities and physical exercise status of participants, types and doses of antipsychotic medications, and major physical conditions, were not reported in most of the included studies. Finally, the efficacy and side effects between different TCMs were not compared due to the small number of studies in each subgroup.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis found that the efficacy of TCM on antipsychotic-related constipation was greater compared to WM, but certain side effects of TCM, such as rash, were less frequent. Hence, TCM appears to be an effective and safe treatment for antipsychotic-related constipation in clinical practice. However, these findings will need to be confirmed in future high-quality studies.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

W-WR, Y-TX, and WZ: study design. W-WR, J-JY, HQ, and SS: data collection, analysis, and interpretation. W-WR, HQ, and Y-TX: drafting of the manuscript. LZ, GU, and CN: critical revision of the manuscript. All authors: approval of the final version for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project for investigational new drug (2018ZX09201-014), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. Z181100001518005), and the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer XW declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with several of the authors, HQ, SS, and LZ, to the handling Editor. The reviewer QL declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with several of the authors, HQ, SS, and LZ, to the handling Editor.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610171/full#supplementary-material

References

1. De Hert M, Dockx L, Bernagie C, Peuskens B, Sweers K, Leucht S, et al. Prevalence and severity of antipsychotic related constipation in patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective descriptive study. BMC Gastroenterology. (2011) 11:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-17

2. Lu Y-S, Chen Y-C, Kuo S-H, Tsai C-H. Prevalence of antipsychotic drugs related to constipation in patients with schizophrenia. Taiwan J Psychiatry. (2016) 30:294–9.

3. Shirazi A, Stubbs B, Gomez L, Moore S, Gaughran F, Flanagan RJ, et al. Prevalence and predictors of clozapine-associated constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. (2016) 17:863. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060863

4. Freudenreich O, Goff DC. Colon perforation and peritonitis associated with clozapine. J Clin Psychiatry. (2000) 61:950. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v61n1210e

5. De Hert M, Hudyana H, Dockx L, Bernagie C, Sweers K, Tack J, et al. Second-generation antipsychotics and constipation: a review of the literature. Eur Psychiatry. (2011) 26:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.03.003

6. Talley NJ, Jones M, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Risk factors for chronic constipation based on a general practice sample. Am J Gastroenterol. (2003) 98:1107–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07465.x

7. Nielsen J, Meyer JM. Risk factors for ileus in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2012) 38:592–8. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq137

8. Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA, et al. Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry. (2006) 163:611–22. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.611

9. Every-Palmer S, Nowitz M, Stanley J, Grant E, Huthwaite M, Dunn H, et al. Clozapine-treated patients have marked gastrointestinal hypomotility, the probable basis of life-threatening gastrointestinal complications: a cross sectional study. EBioMedicine. (2016) 5:125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.020

10. West S, Rowbotham D, Xiong G, Kenedi C. Clozapine induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: a potentially life threatening adverse event. Rev Lit Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2017) 46:32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.02.004

11. Arnaud M. Mild dehydration: a risk factor of constipation? Eur J Clin Nutr. (2003) 57:S88–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601907

12. Gallagher P, O'Mahony D. Constipation in old age. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. (2009) 23:875–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.09.001

13. Cheng CW, Zhao-Xiang B, Tai-Xiang W. Systematic review of Chinese herbal medicine for functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol. (2009) 15:4886–95. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4886

14. Lin L-W, Fu Y-T, Dunning T, Zhang AL, Ho T-H, Duke M, et al. Efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine for the management of constipation: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. (2009) 15:1335–46. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0373

15. Zhai J, Li Y, Lin J, Dong S, Si J, Zhang J. Chinese herbal medicine for postpartum constipation: a protocol of systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e023941. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025891

16. Eliasvandi P, Khodaie L, Mohammad Alizadeh Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M. Effect of an herbal capsule on chronic constipation among menopausal women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Avicenna J Phytomed. (2019) 9:517–29. doi: 10.22038/AJP.2019.13109

17. Zhong LLD, Cheng CW, Kun W, Dai L, Hu DD, Ning ZW, et al. Efficacy of MaZiRenWan, a Chinese herbal medicine, in patients with functional constipation in a randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 17:1303–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.005

18. Chen P, Jiang L, Geng H, Han X, Wu S, Wang Y, et al. Effectiveness of Xinglouchengqi decoction on constipation in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J Tradit Chin Med. (2020) 40:112–20. doi: 10.19852/j.cnki.jtcm.2020.01.012

19. Huang T, Zhao L, Lin CY, Lu L, Ning ZW, Hu DD, et al. Chinese herbal medicine (MaZiRenWan) improves bowel movement in functional constipation through down-regulating oleamide. Front Pharmacol. (2020) 10:1570. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01570

20. Jin ZH, Liu ZT, Kang L, Yang AR, Zhao HB, Yan XY, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial of Bushen Yisui and Ziyin Jiangzhuo formula for constipation in Parkinson disease. Medicine. (2020) 99:e21145. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021145

21. Every-Palmer S, Newton-Howes G, Clarke MJ. Pharmacological treatment for antipsychotic-related constipation. Schizophr Bull. (2017) 43:490–2. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx011

22. Every-Palmer S, Newton-Howes G, Clarke MJ. Pharmacological treatment for antipsychotic-related constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017) 1:CD011128. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011128.pub2

23. Fan YW, Luo WL. Clinical study on treatment of constipation caused by antipsychotic drugs with acupuncture and Tuina combined with laxative suppository. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. (2004) 2:51–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02845405

24. Wang SM, Wang GZ. Oral administration of 10% mannitol treatment of psychiatric drug-induced constipation (in Chinese). J Zhangjiakou Med Coll. (1995) 2:110–1.

25. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151:264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

26. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. (1996) 17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

27. Higgins JPT, Green S editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration Version 5.1.0 (2011).

28. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. (2004) 328:1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490

29. Zhao LM, Wang YX, Sun SH, Zou JH. Senna treatment for drug-induced constipation: a double-blind, randomized controlled tria (in Chinese). Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. (1993) 5:107–8.

30. Ding ZM. Study on the best therapy for neuroleptic-induced astriction (in Chinese). J Nurs Sci. (1998) 13:197–9.

31. Wang LH, Dong GH, Li JK. Clinical observation on senna in the treatment of 89 cases with clozapine-induced constipation (in Chinese). Shanxi J Tradit Chin Med. (1998) 14:10–1.

32. Liu ZJ, He L, Yao DG, Zhai HJ. Clinical research of Yu Zhu Shu Tong treatment on antipsychotic-induced constipation (in Chinese). Med J Chin Civil Admin. (2001) 13:333. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0369.2001.06.031

33. Hu CR, Jiang YB, Nie S. Clinical observation on senna in the treatment for constipation in patients with psychiatric disorders (in Chinese). J Nurs Sci. (2002) 17:338–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-4152.2002.05.007

34. Li CW. Clinical observation on Apricot Seed and Linum Formula in the treatment of 261 cases with antipsychotic-related constipation (in Chinese). Chin J Geriatr Care. (2003) 1:33–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-4860-B.2003.03.010

35. Zhang ZF. Qi Rong Run Chang oral liquid treatment for antipsychotic-induced constipation: a randomized controlled tria (in Chinese). Henan J Pract Nerv Dis. (2003) 6:115. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5110.2003.06.087

36. Li KQ, Xu Y, Jiang Y. Clinical observation on Peony and Licorice combination in the treatment of 52 cases with chlorpromazine-induced constipation (in Chinese). Acta Academiae Medicinae Zunyi. (2005) 28:470–1. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-2715.2005.05.036

37. Li XY, Wang XL. Clinical study on treatment of antipsychotic-related constipation with Rhubarb and Mirabilite and Magnolia Officinalis Rehd et wils formula (in Chinese). J Nurs Sci. (2005) 20:43–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-4152.2005.13.025

38. Sheng CD, Xie LY. Clinical study on treatment of antipsychotic-related constipation with oral 10 % Mannitol (in Chinese). Chronic Pathematol J. (2006) 12X: 45–6.

39. Meng QL, Zhang FY, Ruan JQ, Xu LR. A clinical control study between Senna and phenolphthalein in treatment of the coprostasis about patient with psychosis (in Chinese). Medicine World. (2007) 3:51–3.

40. Wang ZF, Sun SG. Clinical research of Tongfu qingyu decoction treatment on antipsychotic-induced constipation (in Chinese). Chin J Postgrad Med. (2007) 30:20–1. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4904.2007.z2.011

41. Du YH, Yi ZH, Deng HY, Long B. Clinical study on treatment of antipsychotic-related constipation with constipation-relief capsule (in Chinese). J Mod Clin Med. (2008) 7:43–4.

42. Han YD, Ding LY, Liu GM, Yue DH. Clinical effective analysis of senne and rhubarb and phenolphthalein in the treatment of 150 patients with drug-induced constipation. Chin J Pract Chin Mod Med. (2008) 21:1619–20.

43. Lin H, Zhang HY, Xiang XX. Clinical observation on traditional chinese medicine in the treatment of 68 cases with antipsychotic-induced constipation (in Chinese). Nei Mongol J Tradit Chin Med. (2008) 7:17–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-0979.2008.07.007

44. Xie ZY, Yao XF, Su M, Zhao YH. Clinical study on treatment of antipsychotic-related constipation with three methods of catharsis (in Chinese). Int Med Health Guid. (2008) 14:52–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-1245.2008.09.021

45. Jiang XJ. Clinical study on treatment of antipsychotic-related constipation with Peony and Licorice combination (in Chinese). Chin Commun Doctors. (2009) 19:120. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-614x.2009.19.159

46. Liu BZ, Zhang J. Clinical observation on Rheum Glycyrrhiza decoction in the treatment of 163 pasychatic patients with constipation (in Chinese). Shandong Med J. (2010) 50:31. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2010.52.016

47. Li ZY. Clinical research of Maren Runchang Wan treatment on clozapine-induced constipation: a randomized controlled tria (in Chinese). China Foreign Med Treat. (2011) 12:118. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-0742.2011.12.093

48. Pan HP, Wu GX. Comparative observation on laxative drug treatment of constipation (in Chinese). J Henan Univ Sci Technol (Med Sci). (2012) 30:131–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-688X.2012.02.026

49. Wang ZL, Yu X, Li ZC, Li ZX. Clinical study on treatments of constipation caused by antipsychotic drugs (in Chinese). J Front Med. (2013) 19:20. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-1752.2013.19.015

50. Chen X, Yang Q. Clinical research of lactulose treatment on antipsychotic-induced constipation (in Chinese). Chin J Clin Ration Drug Use. (2014) 17:72. doi: 10.15887/j.cnki.13-1389/r.2014.17.122

51. Tian JB, Wang BM. Clinical observation on honeyed glycyrrhiza compound decoction in the treatment of 60 patients with drug-induced constipation (in Chinese). Henan Tradit Chin Med. (2014) 34:1226–7. doi: 10.16367/j.issn.1003-5028.2014.07.012

52. Han ZM. Clinical observation on Chinese medicine laxative capsule in the treatment of 50 cases with antipsychotic-related constipation (in Chinese). Nei Mongol J Tradit Chin Med. (2015) 4:8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-0979.2015.04.008

53. Ye FZ, Zhang SJ, Chen YL. Clinical study on treatment of antipsychotic-related constipation with Maren Ruan capsule (in Chinese). Chin Tradit Herbal Drugs. (2016) 47:2502–5. doi: 10.7501/j.issn.0253-2670.2016.14.019

54. Zhao JT, Tong YR, Yang YH, Huang J, Wang DB, Yang B. 40ml Glycerine with retention enema treatment for psychiatirc patients with constipation (in Chinese). J Today Health. (2016) 15:186. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-5160.2016.07.173

55. Tang Y. Clinical efficacy of TCM medicine on constipation from clozapine (in Chinese). Clin J Chin Med. (2018) 10:84–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7860.2018.16.038

56. Wang Z, Liao JL, Zhong YH. Analysis on curative effect of Maren soft capsules on inpatients with schizophrenia complicated with constipation (in Chinese). China Med Pharm. (2019) 9:194–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-0616.2019.01.056

57. Zhu Q. A randomized controlled trial of lactulose for antipsychotic-related constipation (in Chinese). Home Med. (2019) 7:127–8.

58. Wu XH, Cao GR. Clinical study on treatment of antipsychotic-related constipation with Peony and Licorice Combination (in Chinese). Health Everyone. (2020) 8:96.

59. He JC, Wen R. Diagnosis and treatment of constipation: a perspective of traditional Chinese medicine (in Chinese). Liaoning J Tradit Chin Med. (1998) 5:110.

60. Thompson W, Longstreth G, Drossman D, Heaton K, Irvine E, Müller-Lissner S. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. (1999) 45(Suppl. 2):II43–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43

62. Gastrointestinal Dynamics Group of Chinese Digestive Society. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation (in Chinese). Chin Gen Pract. (2005) 8:119–21. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-9572.2005.02.016

63. Ardern-Jones MR, Friedmann PS. Skin manifestations of drug allergy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2011) 71:672–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03703.x

64. Chae B-J, Kang B-J. Rash and desquamation associated with risperidone oral solution. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. (2008) 10:414. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v10n0511e

65. Nath S, Rehman S, Kalita KN, Baruah A. Aripiprazole-induced skin rash. Ind Psychiatry J. (2016) 25:225. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.207862

66. Shah M, Karia S, Merchant H, Shah N, De Sousa A. Olanzapine-induced skin rash: a case report. Telangana J Psychiatry. (2019) 5:70–1. doi: 10.18231/j.tjp.2019.013

67. Wang M, Li MC, Wang JH, Xin X, Ren L. Traditional medicine for antipsychotic drugs induced constipation: a bibliometric analysis of clinical studies. Adv Integr Med. (2019) 6:S115. doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2019.03.333

68. World Traditional Medcine Forum. Law of the People's Republic of China on Traditional Chinese Medicine. (2020). Available online at: http://www.worldtmf.org/index/article/view/id/14008.html (accessed January 16, 2021).

69. Pan HP, Duan YS. Observation on 48 cases of drug-induced constipation treated by modified cannabis seed pills (in Chinese). J Pract Tradit Chin Med. (2010) 3:150–1. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-2814.2010.03.003

70. Qi H, Liu R, Zheng W, Zhang L, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. Efficacy and safety of traditional Chinese medicine for Tourette's syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asian J Psychiatry. (2020) 47:101853. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101853

71. Song J, Bai T, Zhang L, Hou XH. Clinical features and treatment options among Chinese adults with self-reported constipation: an internet-based survey. J Dig Dis. (2019) 20:409–14. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12792

72. Yun LJ. The impact of traditional chinese medicine pharmaceutical care on the medication compliance (in Chinese). Hosp Dir Forum. (2014) 4:47–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-1700.2014.04.420

73. Dong M, Zeng LN, Zhang Q, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Chiu HF, et al. Concurrent antipsychotic use in older adults treated with antidepressants in Asia. Psychogeriatrics. (2019) 19:333–9. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12416

74. Liu JF, Tong Y, Huang Y, Liu M, Ma J, Song T. Clinical efficacy and adverse effects of first and second generation antipsychotics (in Chinese). J Clin Psychosom Dis. (2008) 14:111–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-187X.2008.02.006

Keywords: meta-analysis, randomized controlled study, constipation, traditional Chinese medicine, antipsychotic

Citation: Rao W-W, Yang J-J, Qi H, Sha S, Zheng W, Zhang L, Ungvari GS, Ng CH and Xiang Y-T (2021) Efficacy and Safety of Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine for Antipsychotic-Related Constipation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Psychiatry 12:610171. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610171

Received: 28 September 2020; Accepted: 09 March 2021;

Published: 29 April 2021.

Edited by:

Mirko Manchia, University of Cagliari, ItalyReviewed by:

Xin Li, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, ChinaXiao Ma, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Xiaomin Wang, Capital Medical University, China

Qingquan Liu, Capital Medical University, China

Copyright © 2021 Rao, Yang, Qi, Sha, Zheng, Zhang, Ungvari, Ng and Xiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chee H. Ng, Y25nQHVuaW1lbGIuZWR1LmF1; Yu-Tao Xiang, eHl1dGx5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Wen-Wang Rao

Wen-Wang Rao Juan-Juan Yang

Juan-Juan Yang Han Qi

Han Qi Sha Sha6†

Sha Sha6† Wei Zheng

Wei Zheng Ling Zhang

Ling Zhang Chee H. Ng

Chee H. Ng Yu-Tao Xiang

Yu-Tao Xiang