- 1Department of Psychiatry, Chaohu Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Anhui Psychiatric Center, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

- 3Healthcare Management and Evaluation Research Center, Institute of Health Yangtze River Delta, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

- 4Research Center for Public Health, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

- 5Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 6Institute for Hospital Management of Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

- 7Public Health School, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

- 8Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Decatur, GA, United States

Objectives: Mental healthcare has gained momentum and significant attention in China over the past three decades. However, many challenges still exist. This survey aimed to investigate mental health resources and the psychiatric workforce in representative top-tier psychiatric hospitals in China.

Methods: A total of 41 top-tier psychiatric hospitals from 29 provinces participated, providing data about numbers and types of psychiatric beds, numbers of mental health professionals, outpatient services and hospitalization information covering the past 3 years, as well as teaching and training program affiliation.

Results: Significant variations were found among participating hospitals and across different regions. Most of these hospitals were large, with a median number of psychiatric beds of 660 (range, 169-2,141). Child and geriatric beds accounted for 3.3 and 12.6% of all beds, respectively, and many hospitals had no specialized child or geriatric units. The overall ratios of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, and psychologists per bed were 0.16, 0.34, and 0.03, respectively. More than 40% of the hospitals had no clinical social workers. Based on the government's staffing guidelines, less than one third (31.7%) of the hospitals reached the lower limit of the psychiatric staff per bed ratio, and 43.9% of them reached the lower limit of the nurse per bed ratio.

Conclusion: Although some progress has been made, mental health resources and the psychiatric workforce in China are still relatively insufficient with uneven geographical distribution and an acute shortage of psychiatric beds for children and elderly patients. In the meantime, the staffing composition needs to be optimized and more psychologists and social workers are needed. While addressing these shortages of mental health resources and the workforce is important, diversifying the psychiatric workforce, promoting community mental health care, and decentralizing mental health services may be equally important.

Introduction

Psychiatry and mental health services in China have been traditionally marginalized with limited resources allocated (1–3), however, some positive progress has been noticed. In recent decades these areas have gained certain momentum and significant attention from the public and the government (4), in large part due to recent studies showing the high rates of mental disorders (5, 6) in the population, the increasing global burden of mental disorders, as measured by the disability adjusted life years (DALYs) (7), and the impact of mental disorders on labor market and workplace productivity (8). A recent national mental health survey (9) was conducted in 31 provinces across China and it found the lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder was 16.6%, while the 12-month prevalence was 9.3%. On the other hand, the estimated disability adjusted life years (DALYs) in thousands by mental and substance use disorders reached 31,095.0 years in China in 2016 (30,368.7 years in 2010, and 31,014.0 years in 2015), which accounted for 8.3% of the total disease burden of China, and 18.2% of the global burden of mental and substance use disorders (10).

Facing increasing challenges in mental health care, great efforts have been made in China to reform the mental health service system (4, 11). One milestone is China's very first Mental Health Law (MHL) (implemented in 2013) (12), which is comprehensive, and involves many aspects of mental health services, including the budget, resources, community services, patients' rights, and professional training. Subsequently, the National Mental Health Work Plan (2015–2020) (13) requires improving the system and network of mental health services and mandating each county (city, district) set up a psychiatric department in at least one general hospital. To increase the supply of the psychiatric workforce, 31 medical colleges across China have established psychiatry programs for medical students with vigorous promotion by the National Health Commission and Ministry of Education. These are specialized programs with a curriculum focusing on psychiatry-related teaching, with the goal to fast-track graduates to psychiatry residency directly (14). Now, there are total 6,271 medical students in psychiatry programs in medical colleges, and 720 students graduated in 2018.

With all these efforts, significant progress has been made in bolstering mental health resources and the psychiatric workforce across the country. The number of psychiatric beds nationwide increased from 228,100 (17.1 per 100,000 population, same units hereafter unless otherwise specified) in 2010 to 433,090 (31.5) in 2015, with a growth rate of 89.9% (15). There were 13 provinces with an increase of more than 100% in the number of psychiatric beds (Top three provinces: Guizhou with an increase of 241.4%, Jiangxi with 192.5%, and Hunan with 172.9%, respectively). The government has put forward a plan to strengthen the mental health service system in the central and western regions and on a national level (15). The numbers of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses increased from 20,480 (1.54) and 35,337 (2.65) in 2010 (16) to 30,122 (2.19) and 75,765 (5.51) in 2015 (15), respectively. By the end of 2018, there were 506,637 psychiatric beds (36.3) and about 36,000 psychiatrists (2.58), including licensed psychiatrists and psychiatric registrars in China (17), which are slightly above the average (or median) levels in upper middle-income countries (UMICs) (24.3 and 2.11, respectively) (18).

However, several insufficiencies in mental health resources and workforce of China remain. First, for the most part, mental health services in China are organized around psychiatric hospitals, which provide nearly 80% of mental health services (78.8% of all beds, and 78.4% of mental health workers) in China, followed by psychiatric departments in general hospitals (16.8 and 17.3%), primary care settings (3.8 and 3.1%), and rehabilitation hospitals (1.4 and 0.9%) (15). This is very different from many other countries. The reality is, except for a few major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou (Canton), community mental health services are rather limited and psychiatric hospitals remain as the main or even the only mental health provider in most places. Second, mental health resources are even more limited for key population subgroups, including the elderly and children. Third, relative to the mental health workforce located in UMICs, the total number of Chinese mental health workers is small (8.90 vs. 20.6 per 100,000 population) and staffing composition is different from that in UMICs (5.51 vs. 6.83 psychiatric nurses, 0.35 vs. 1.89 psychologists, and 0.11 vs. 0.50 social workers per 100,000 population) (15, 18), with psychologists and social workers disproportionally understaffed.

To date, no detailed data at the hospital level are available to enable suitable analysis and guidance on the allocation of mental health resources and the psychiatric workforce in China. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate and analyze the resources and the workforce based on several new indicators in representative top-tier psychiatric hospitals in China, and hope to use the data to optimize resource allocation and staffing to improve hospital-based mental health service in China.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study was part of the 2019 National Hospital Performance Evaluation Survey (NHPES). It focused on the topic of mental health services, aiming to identify current deficiencies and imbalances in China's mental health care and to ultimately improve its quality. Basic information about each hospital was filled out by staff members in the hospitals' medical management departments through an online questionnaire survey from March 18 to 31, 2019. A paper document with the hospital manager's signature, contact information, and hospital seal was subsequently requested to be submitted. As a result of the assurance of a notification issued by each Provincial Health Commission, participation rate of target hospitals reached 100%. The psychiatric investigation project had been approved by the Ethics Committee of Chaohu Hospital of Anhui Medical University (No. 201903-kyxm-02) before the study began.

In total, 41 tertiary psychiatric hospitals from 29 provinces and autonomous regions in China were investigated and coded as P1–P41. Two provinces, Gansu and Tibet, had no provincial tertiary psychiatric hospitals at the time of survey and therefore were not included. According to the classification of Chinese economic regions reported by the National Bureau of Statistics (19), four regions were ranked by the number of top-tier psychiatric hospitals: East China (14 hospitals), West China (12 hospitals), Central China (nine hospitals), and Northeast China (six hospitals) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Geographical distribution and basic data of 41 participating psychiatric hospitals in China. H, number of hospitals; B, number of psychiatric beds.

Data Collection

The questionnaire about resources and the workforce was designed for these hospitals above to collect psychiatric bed data (i.e., number of psychiatric beds in closed-door, open-door, child, and geriatric wards, and occupancy rate), psychiatric workforce composition (i.e., number of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, psychologists, and social workers), outpatient services and hospitalization information (i.e., outpatient visits, average hospitalization days, and number of discharged patients) in the past 2 years, teaching and training program affiliation, and other relevant information. The supplementary hospitalization information of 32 hospitals (P1–P32) in 2016 was extracted from the NHPES conducted in 2017 (20).

To exclude resources related to non-psychiatric services provided in 15 of the 41 hospitals (P12, P16, P21, P22, P23, P24, P26, P27, P32, P34, P35, P36, P37, P38, and P41), we conducted a second survey from October 18 to 31, 2019. Data about psychiatric standardized residency training programs (2019) were obtained from their official websites in each province. All data collection and entry were double checked.

Indicators About Staffing and Setting

We collected the numbers of psychiatric beds (including beds in closed-door wards and open-door wards), psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, psychologists/ therapists and social workers in each hospital. Based on these numbers, we calculated different ratios as indicators of staffing adequacy and composition: They include: the number of psychiatrists/number of beds (P/B ratio); psychiatric nurses/beds (N/B ratio); psychiatric nurses/psychiatrists (N/P ratio). The staffing guidelines in tertiary psychiatric hospitals (21) recommended by National Health Commission of China was as follows: at least 0.55 healthcare professionals per bed with an average of at least 0.35 nurses per bed. Because most of the time, doctors and nurses are the primary providers working directly with patient care in the inpatient setting in China, the sum of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses was substituted for the number of healthcare professionals in the data analysis. Variation in outpatient visits, average hospitalization days, and number of discharged patients in these psychiatric hospitals from 2016 to 2018 were also calculated as they reflect the current need for mental health services in China. In addition, the psychiatrists in these hospitals were required to provide mental health services in the outpatient clinic for outpatients, therefore, the ratio of outpatient visits (2018 data) /psychiatrists (OVs/P) was calculated for measuring the overall productivity of the psychiatrists' outpatient work.

Data Analysis

Statistical descriptions and analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS, version 23.0. Frequency distributions and medians were calculated for qualitative and quantitative variables, respectively, and weighted ratios for P/B, N/B, N/P, and OVs/P. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to detect the distribution normality of variables (n < 50). Outpatient visits (OVs), average hospitalization days (AHDs), and number of discharged patients (DPs) between adjacent years were compared by using Paired-Samples T Test or Two Related-Samples Test (Wilcoxon), as appropriate. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (2- tailed).

Results

Psychiatric Bed Settings

The median number of total psychiatric beds was 660 (range, 169-2,141) in 41 top-tier psychiatric hospitals in China (Table 1). 80.5% (33/41) had ≥500 psychiatric beds, nearly two thirds (26/41, 63.4%) had a bed occupancy rate of over 100 percent. The median number of psychiatric beds in closed-door wards and open-door wards were 535 (range, 124–2093) and 120 (range, 20–452), respectively. Regarding the psychiatric bed settings for special populations, we found that 75.6% (31/41) of these hospitals had a child psychiatric unit and 90.2% (37/41) had a geriatric unit. Overall, child and geriatric beds only accounted for 3.3 and 12.6% of all psychiatric beds, respectively.

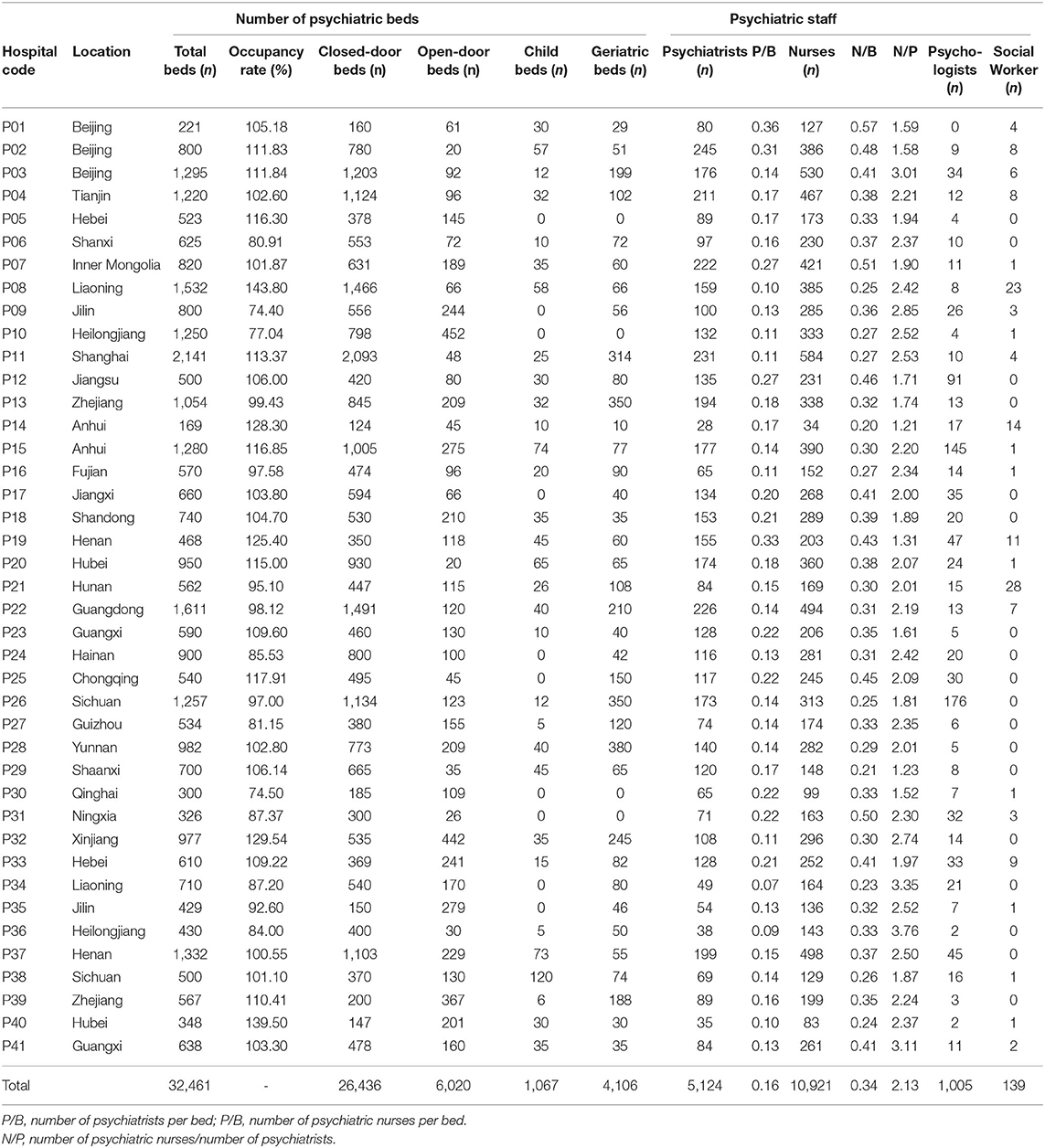

Table 1. Number of psychiatric beds and staff composition in 41 top-tier psychiatric hospitals in China.

Psychiatric Workforce and Its Composition

The median number of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses were 117 (range, 28–245) and 245 (range, 34–584) in these hospitals (Table 1). The overall ratios of P/B and N/B were 0.16 and 0.34 per bed, respectively, with wide variations across different hospitals (from 0.07 to 0.36, and 0.20 to 0.57). Using the staffing guidelines set by the government, less than one third (31.7%) of the hospitals reached the lower limit of the staffing ratio, and 43.9% of them reached the lower limit of nurses per bed. The overall ratio of N/P was around 2:1, and again with a wide variation among different hospitals (from 1.21 to 3.76, more than three times).

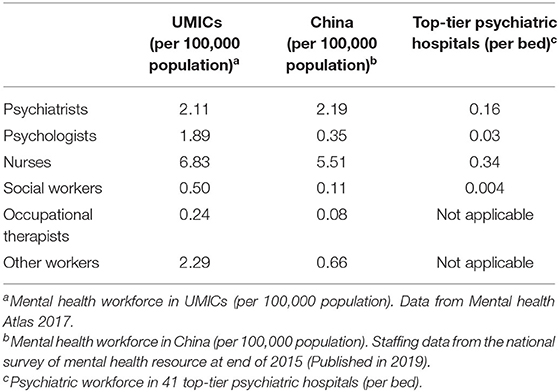

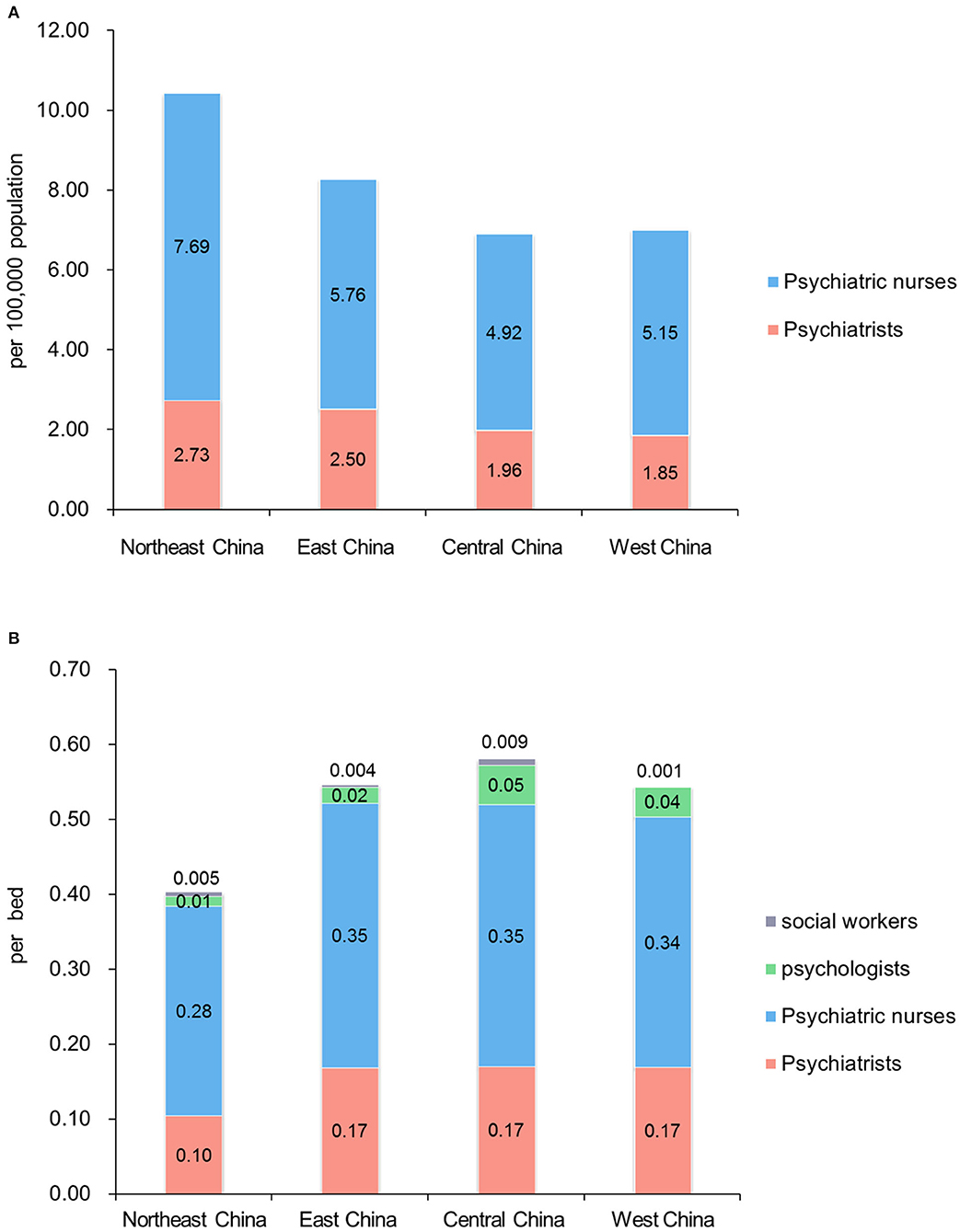

The total number of psychologists was 1,005, and the ratio of psychologists to beds was 0.03 per bed. Notably, 43.9% (18/41) of these hospitals had no social workers. In all, the number of social workers was only 139 in these 41 top-tier psychiatric hospitals. Table 2 showed the staffing composition in UMICs, China, and this survey, and Figure 2 showed the comparison of mental health workforce in different regions in China and this survey.

Table 2. Staffing composition in upper middle income countries (UMICs), China, and data from this survey.

Figure 2. Comparison of mental health workforce in different regions in China, and data from this survey. (A) Mental health workforce (psychiatrists and nurses only) in different regions in China (per 100,000 population). Staffing data from the national survey at end of 2015, and provincial demographic data from Chinese Health Statistical Yearbook 2019. Numbers of other mental health workers by region were not available. (B) Psychiatric workforce in different regions in 41 top-tier psychiatric hospitals (per bed).

Outpatient Services and Hospitalization

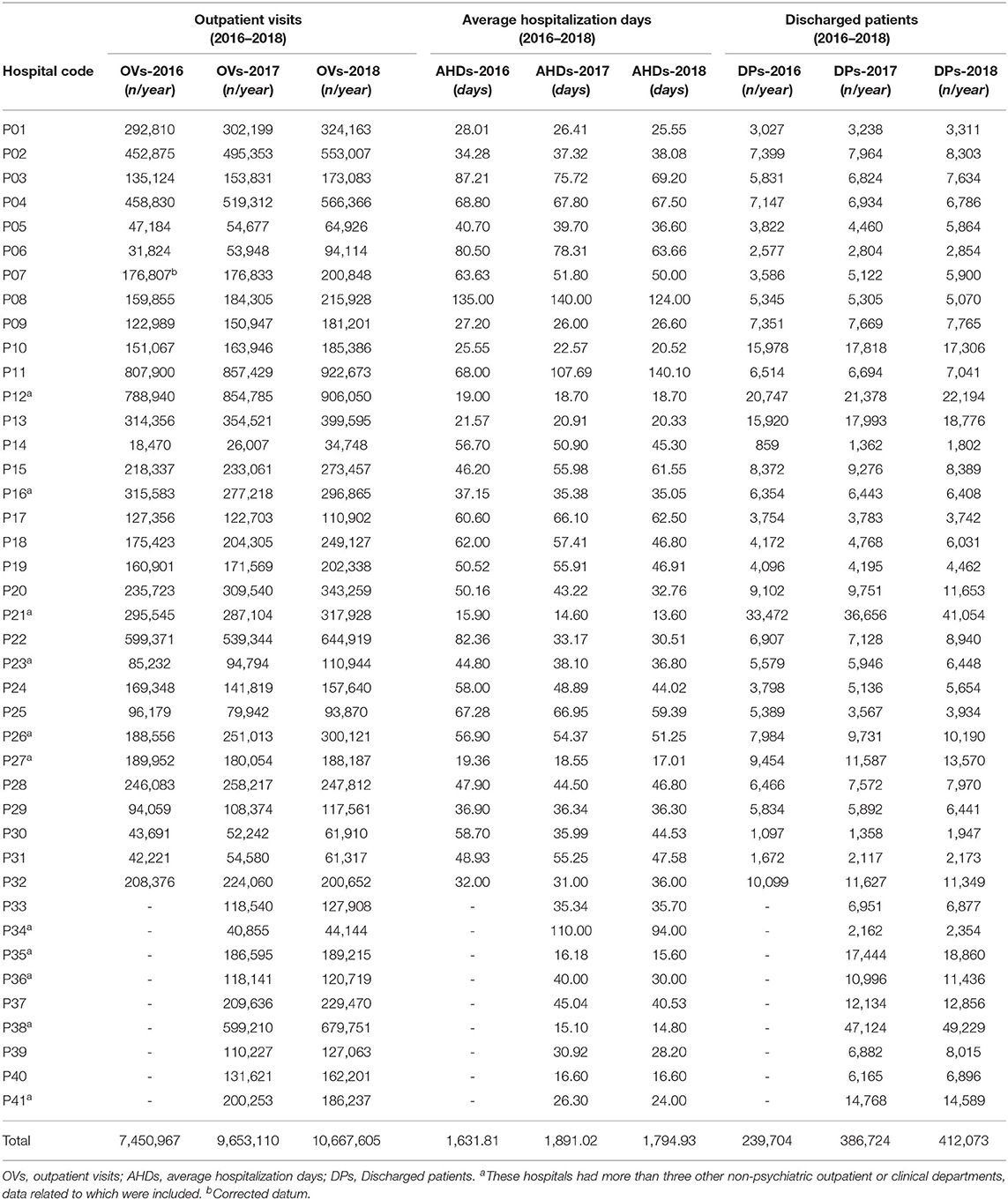

Overall, OVs, and DPs increased from 2016 to 2018, while AHDs decreased (Table 3). The medians of ΔOVs, ΔDPs, and ΔAHDs were 32,836 (range, −18,718–117,110), 924 (range, −1,455–7,582), and −3.04 (range, −51.85–72.10) in 32 hospitals, respectively. Significant statistical differences were observed in OVs (t = −2.931, p = 0.006), DPs (Z = −4.226, p < 0.001), and AHDs (Z = −2.001, p = 0.045) between 2016 and 2017, and OVs (t = −6.242, p < 0.001), DPs (Z = −4.231, p < 0.001), and AHDs (Z = −3.217, p = 0.001) between 2017 and 2018, which reflects the demands for psychiatric outpatient services and hospitalization increasing year by year. After removal of the hospitals that had more than three other non-psychiatric outpatient or clinical departments, the differences remained significant in OVs (t = −2.978, p = 0.006), and DPs (Z = −3.619, p < 0.001) between 2016 and 2017, and OVs (t = −5.604, p < 0.001), DPs (t = −3.798, p < 0.001), and AHDs (Z = −2.303, p = 0.021) between 2017 and 2018.

Table 3. Outpatient visits, average hospitalization days, and discharged patients in 41 top-tier psychiatric hospitals in China from 2016 to 2018.

In addition, the ratio of OVs/P was 1,730.5, ranging from 729.5 to 4,634.3 in 26 psychiatric hospitals with only psychiatric outpatient departments. Assuming all listed psychiatrists worked at outpatient clinics for 104 days/year (2 days a week), then each psychiatrist saw between 7 and 45 patients every working day. Considering many psychiatrists do not work in the outpatient clinic, the actual caseload of each psychiatrist was much higher than this.

Psychiatric Medical Education and Standardized Residency Training

Ninety point two percent (37/41) of the hospitals surveyed were teaching hospitals affiliated with a medical college. Eighty seven point eight percent (36/41) had a psychiatric residency training program, and there were 391 trainees (N/A in three hospitals) in 2019. In all, 1,322 psychiatric residents were newly recruited in the 26 provinces and regions (N/A in three provinces) of China in 2019 (Supplementary Table 1). There were large differences in the numbers of psychiatric residents in provincial recruitment plans with the most (749 psychiatric residents) recruited from provinces in East China, a socioeconomically developed region.

Discussion

In this study, significant efforts were taken to collect accurate data about mental health resources and the psychiatric workforce in 41 top-tier psychiatric hospitals from 29 provinces and autonomous regions across China. All of these hospitals are located in urban centers, representing the best psychiatric resources available in China.

Our findings are both encouraging and concerning. While we found the overall number of mental health professionals in top-tier psychiatric hospitals has increased over the past decade, a few areas clearly need improvement and change. The results showed that although 80% of these hospitals had more than 500 beds, more than 60% still had a bed occupancy rate of over 100 percent, an indicator that more psychiatric beds are needed or more community resources need to be developed. When “extra or temporary” beds are added to accommodate more patients or for economic reasons, safety and security problems may arise.

The non-existence or shortage of child and geriatric psychiatric beds in some provinces or regions is very concerning as well. Due to their unique developmental features, children and adolescents who require inpatient care for mental health problems should be managed in age-appropriate facilities (22). Similarly, due to their special needs in mobility, cognition and other age-related issues, elderly patients often need to be in a specially designed and staffed unit.

According to the most recent data (23), by the end of 2018, the number of children (aged 0–14 years) in China reached 16.9% of the Chinese population (1.395 billion); and the number of elderly (aged ≥65 years) reached 11.9%, and it has been growing for the past 23 years. The prevalence of mental disorders are high in both children (9–10%) (24, 25) and the elderly (4.9%) (9). One recent report showed that there were only 3,825 child psychiatric beds (0.89%) and 28,118 geriatric psychiatric beds (6.49%) nationwide in China (2015 data) (15). In this study, we found 10/41 (24.4%) hospitals did not have a child unit, and 4/41 (9.8%) did not have either a child or a geriatric unit. The overall child and geriatric beds accounted for 3.3 and 12.6% of all beds, respectively. Although they were expectedly higher than the national rate (0.89 and 6.49%, respectively), they were still quite limited. It is known that many children with mental disorders are rejected from hospitals or they are hospitalized with adults, causing safety and other concerns. According to a recent report, there are fewer than 500 full-time child psychiatrists in China, and the distribution is uneven (26).

Of note, we found that the number of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses relative to beds was small in top-tier psychiatric hospitals, although these numbers have increased over the past few years on a national scale. There was also a very limited number of psychologists in these hospitals (0.03 per bed, one psychologist for 30 beds), and there were virtually no psychologists in some hospitals, or psychologists working on inpatient units. According to the estimated number of mental health workers needed in 44 middle-income countries (MICs) (1.5 psychiatrist, 15.0 nurses, and 10.2 psychosocial care providers per 100,000 population) (15, 27), there was a serious shortage of 135,000 psychologists/therapists (9.85 per 100,000) in China by the end of 2015.

Mental health services involve multidisciplinary teams. In addition to psychiatrists and nurses, the roles of psychologists, social workers, and peer specialists are very important and even essential (28, 29). With effective short-term training and supervision, non-specialist health workers including social workers and lay workers may contribute to mental health services in psychiatric hospitals and other settings (29, 30). In this survey, 43.9% (18/41) of the hospitals did not have a single social worker, and only 9.8% (4/41) had more than 10 social workers in their workforce. This is extraordinary and it also means that the psychiatrists in these hospitals often need to take on the role of therapist and social worker at times, in addition to their traditional responsibilities.

As a neighboring country, the situation in Japan may provide some reference. In Japan, there were 11.87 psychiatrists, 83.81 psychiatric nurses, 3.04 psychologists, and 8.33 social workers per 100,000 population, making the shortage of mental health workers in China more pronounced (18).

The current demands for both outpatient and inpatient mental healthcare in China are growing, as measured by changes in OVs, DPs, and AHDs in these top-tier psychiatric hospitals from 2016 to 2018. Since the 1980s, meeting patients' demand in the outpatient setting in China has been a widespread problem, which is fundamentally caused by the unbalanced distribution of mental health resources and the workforce. The low-income population has increased risks of mental health problems, but little access to mental healthcare (31). In China, the 12-month rate of professional contact coverage for any mental disorders ranged from 2.7 to 3.4%, and the 12-month rate of effective treatment coverage was only 24.1% (32). Previous investigation of four provinces in China projected that 173 million Chinese adults suffer from mental disorders, of whom 158 million (91.3%) had never received professional services (5). In contrast, 18.6 million (43.1%) of such adults in the United States received professional help in 2015 (33).

China is a hierarchical society where capital cities often have the most healthcare resources. While the hospitals in the study are “large” and many trained professionals work there, the situation overall is rather bleak, especially for those in rural areas. While most well-trained professionals prefer to work and live in urban areas, the overall level of career satisfaction among mental health professionals were either moderate (general job satisfaction) or low (perceived social recognition and respect from the public and patients) and a large percentage of them considered leaving their job (20% among both psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses) (20, 34, 35).

As affiliated hospitals of medical universities or colleges, almost all the hospitals in this study were involved in psychiatric undergraduate education (90.2%, 37/41) and standardized residency training (87.8%, 36/41). In China, a qualified specialist physician is required to receive 5 years of medical (undergraduate) education and 3 years of standardized residency training (36).

A few limitations of this survey should be noted. First, the participating hospitals were all tertiary hospitals, and these hospitals often have more resources than the hospitals at the district- or county-levels, or in rural areas. According to a previous report, although provincial hospitals had 10.8% of all the psychiatric beds, they had 16.0% of mental health workers in China (50.3 and 53.6% in municipal hospitals, and 38.8 and 30.4% in county level hospitals, respectively) (15). As a result, the generalizability of our findings may be limited and our results may actually overestimate the resource allocation and workforce numbers, supporting our overall concerns. Second, we did not include some potentially important data in this survey, such as psychiatrists' subspecialty background, e.g., child psychiatrist, adult psychiatrist, or geriatric psychiatrist; and the nature of the outpatient visits (assessment, medication management, vs. therapy).

Conclusions

In summary, we found a critical shortage of mental health professionals, particularly in less developed regions, and the situation for non-top-tier hospitals is likely worse. The staffing composition of the psychiatric workforce needs to be optimized and more psychologists and social workers must be trained and hired. More beds, especially those serving child and elderly patients are urgently needed. While improving the resources and building the workforce in psychiatric hospitals is important, developing more community-based mental health services are equally, if not more important over the long run. Psychiatric hospitals and community mental health services are part of a system that provides a continuity of care and keeps patients safe.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

FJ, HL, YL, TL, and YLT conceived and planned the survey. LX, YZ, YS, and KZ contributed to the implementation and acquisition of data for this study. LX and FJ did all data analyses and drafted the manuscript. YLT and JR gave many useful suggestions and amended the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Clinical Key Specialty Project Foundation (CN), and the Beijing Medical and Health Foundation (Grant No. MH180924).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the institutions and persons involved in the survey.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.573333/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Phillips MR. Mental health services in China. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. (2000) 9:84–8. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00008253

2. Yip KS. An historical review of the mental health services in the People's Republic of China. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2005) 51:106–18. doi: 10.1177/0020764005056758

3. Tang YL, Sevigny R, Mao PX, Jiang F, Cai Z. Help-seeking behaviors of Chinese patients with schizophrenia admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2007) 34:101–7. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0084-9

4. Liu J, Ma H, He YL, Xie B, Xu YF, Tang HY, et al. Mental health system in China: history, recent service reform and future challenges. World Psychiatry. (2011) 10:210–6. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00059.x

5. Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, Song Z, Ding Z, Pang S, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001-05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet. (2009) 373:2041–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7

6. Liu J, Yan F, Ma X, Guo HL, Tang YL, Rakofsky JJ, et al. Prevalence of major depressive disorder and socio-demographic correlates: Results of a representative household epidemiological survey in Beijing, China. J Affect Disord. (2015) 179:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.009

7. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. (2012) 380:2163–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2

8. Lu C, Frank RG, Liu Y, Shen J. The impact of mental health on labour market outcomes in China. J Ment Health Policy Econ. (2009) 12:157–66.

9. Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:211–24. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X

10. World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates 2016: Disease Burden by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2016. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

11. Xiang YT, Ng CH, Yu X, Wang G. Rethinking progress and challenges of mental health care in China. World Psychiatry. (2018) 17:231–2. doi: 10.1002/wps.20500

12. Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. Mental Health Law of China. Beijing (2012). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2012-10/26/content_2252122.htm (accessed January 1, 2021).

13. General Office of the State Council of China. Work Plan (2015-2020) of National Mental Health. Beijing (2015). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-06/18/content_9860.htm (accessed January 1, 2021).

14. Cui G. Psychiatric Undergraduates Education in China. (2019). Available online at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/glO26HfQu0NeE0YzxlaGgQ (accessed January 10, 2021).

15. Shi C, Ma N, Wang L, Yi L, Wang X, Zhang W, et al. Study of the mental health resources in China. Chin J Health Policy. (2019) 12:51–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2019.02.008

16. Liu C, Chen L, Xie B, Yan J, Jin T, Wu Z. Number and characteristics of medical professionals working in Chinese mental health facilities. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. (2013) 25:277–85. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.05.003

17. National Health Commission of China. Chinese Health Statistical Yearbook 2019. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Press (2019).

19. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Division method of East, West, Central and Northeast China. Beijing (2011). Available online at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/ztjc/zthd/sjtjr/dejtjkfr/tjkp/201106/t20110613_71947.htm (accessed January 1, 2021).

20. Zhou H, Jiang F, Rakofsky J, Hu L, Liu T, Wu S, et al. Job satisfaction and associated factors among psychiatric nurses in tertiary psychiatric hospitals: Results from a nationwide cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. (2019) 75:3619–30. doi: 10.1111/jan.14202

21. National Health Commission of China. Basic Standards for Medical Institutions. Beijing (2017). Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/ewebeditor/uploadfile/2017/06/20170614162520548.docx (accessed January 1, 2021).

22. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Inpatient Hospital Treatment of Children and Adolescents. Washington (1989). Available online at: https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Policy_Statements/1989/Inpatient_Hospital_Treatment_of_Children_and_Adolescents.aspx (accessed January 1, 2021).

23. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Chinese Statistical Yearbook 2019. Beijing: Bureau of Statistics of China (2019).

24. Xiaoli Y, Chao J, Wen P, Wenming X, Fang L, Ning L, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents in northeast China. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e111223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111223

25. Shen YM, Chan BSM, Liu JB, Zhou YY, Cui XL, He YQ, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among students aged 6~ 16 years old in central Hunan, China. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:243. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1823-7

26. Wu JL, Pan J. The scarcity of child psychiatrists in China. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:286–7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30099-9

27. Scheffler RM, Bruckner TA, Fulton BD, Yoon J, Shen G, Chisholm D, et al. Publication on Human Resources for Mental Health: Workforce Shortages in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Geneva: World Health Organization (2011).

28. Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. (2007) 370:1164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X

29. Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, et al. Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet. (2011) 378:1654–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61093-3

30. Sweetland AC, Oquendo MA, Sidat M, Santos PF, Vermund SH, Duarte CS, et al. Closing the mental health gap in low-income settings by building research capacity: perspectives from Mozambique. Ann Glob Health. (2014) 80:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.014

31. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. (2007) 370:878–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2

32. Patel V, Xiao S, Chen H, Hanna F, Jotheeswaran AT, Luo D, et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet. (2016) 388:3074–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00160-4

33. Park-Lee E, Lipari RN, Hedden SL, Kroutil LA, Porter JD. Receipt of Services for Substance Use and Mental Health Issues Among Adults: Results From the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US) (2016). p. 1–35.

34. Jiang F, Hu L, Rakofsky J, Liu T, Wu S, Zhao P, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics and job satisfaction of psychiatrists in China: results from the first nationwide survey. Psychiatr Serv. (2018) 69:1245–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800197

35. Jiang F, Zhou H, Rakofsky J, Hu L, Liu T, Wu S, et al. Intention to leave and associated factors among psychiatric nurses in China: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. (2019) 94:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.03.013

Keywords: mental health, resources, workforce, psychiatric hospitals, China

Citation: Xia L, Jiang F, Rakofsky J, Zhang Y, Shi Y, Zhang K, Liu T, Liu Y, Liu H and Tang YL (2021) Resources and Workforce in Top-Tier Psychiatric Hospitals in China: A Nationwide Survey. Front. Psychiatry 12:573333. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.573333

Received: 16 June 2020; Accepted: 03 February 2021;

Published: 24 February 2021.

Edited by:

Jutta Lindert, University of Applied Sciences Emden Leer, GermanyReviewed by:

Raluca Sfetcu, Spiru Haret University, RomaniaXiangdong Wang, Peking University Sixth Hospital, China

Copyright © 2021 Xia, Jiang, Rakofsky, Zhang, Shi, Zhang, Liu, Liu, Liu and Tang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huanzhong Liu, aHVhbnpob25nbGl1JiN4MDAwNDA7YWhtdS5lZHUuY24=; Yi-lang Tang, eXRhbmc1JiN4MDAwNDA7ZW1vcnkuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Lei Xia

Lei Xia Feng Jiang

Feng Jiang Jeffrey Rakofsky

Jeffrey Rakofsky Yulong Zhang1,2

Yulong Zhang1,2 Kai Zhang

Kai Zhang Yuanli Liu

Yuanli Liu Huanzhong Liu

Huanzhong Liu Yi-lang Tang

Yi-lang Tang