95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry , 19 November 2020

Sec. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Rehabilitation

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586230

This article is part of the Research Topic Design and Implementation of Rehabilitation Interventions for People with Complex Psychosis View all 19 articles

Atul Jaiswal1*

Atul Jaiswal1* Karin Carmichael2

Karin Carmichael2 Shikha Gupta3

Shikha Gupta3 Tina Siemens2

Tina Siemens2 Pavlina Crowley2

Pavlina Crowley2 Alexandra Carlsson2

Alexandra Carlsson2 Gord Unsworth2

Gord Unsworth2 Terry Landry2

Terry Landry2 Naomi Brown2

Naomi Brown2Introduction: There is an increasing emphasis on recovery-oriented care in the design and delivery of mental health services. Research has demonstrated that recovery-oriented services are understood differently depending on the stakeholders involved. Variations in interpretations of recovery lead to challenges in creating systematically organized environments that deliver a consistent recovery-oriented approach to care. The existing evidence on recovery-oriented practice is scattered and difficult to apply. Through this systematic scoping study, we aim to identify and map the essential elements that contribute to recovery outcomes for persons living with severe mental illness.

Methods: We used the Arksey & O'Malley framework as our guiding approach. Seven key databases (MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL/EBSCO, EMBASE, ProQuest, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar) were searched using index terms and keywords relating to recovery and severe mental illness. To be included, studies had to be peer-reviewed, published after 1988, had persons with severe mental illness as the focal population, and have used recovery in the context of mental health. The search was conducted in August 2018 and last updated in February 2020.

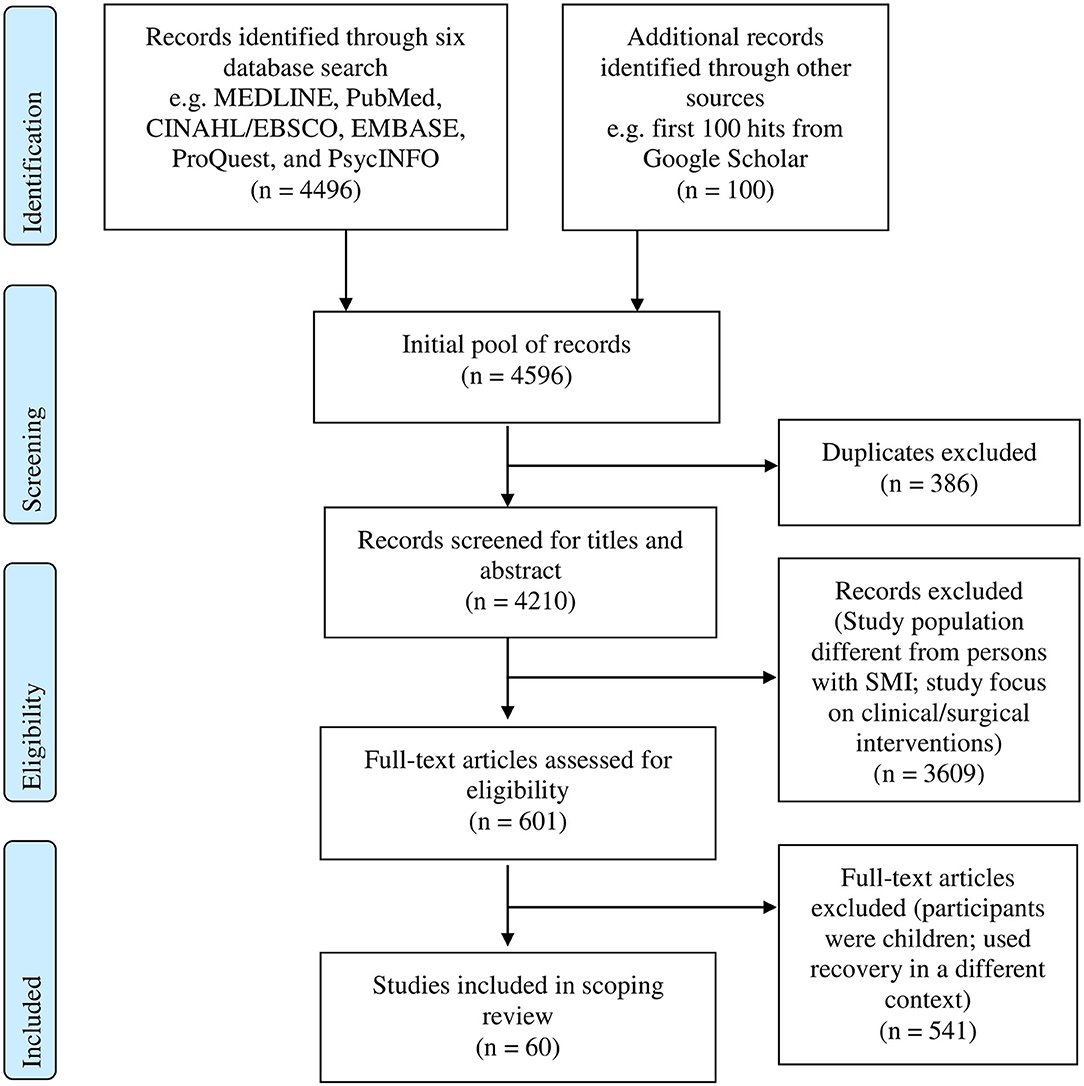

Results: Out of 4,496 sources identified, sixty (n = 60) sources were included that met all of the selection criteria. Three major elements of recovery that emerged from the synthesis (n = 60) include relationships, sense of meaning, and participation. Some sources (n = 20) highlighted specific elements such as hope, resilience, self-efficacy, spirituality, social support, empowerment, race/ethnicity etc. and their association with the processes underpinning recovery.

Discussion: The findings of this study enable mental health professionals to incorporate the identified key elements into strategic interventions to facilitate recovery for clients with severe mental illness, and thereby facilitate recovery-oriented practice. The review also documents important gaps in knowledge related to the elements of recovery and identifies a critical need for future studies to address this issue.

The concept of recovery-oriented care has gained prominence as a philosophical underpinning of the design and delivery of mental health services (1, 2). The recovery approach challenges previously held paternalistic beliefs regarding treatment and prognosis, allowing for a more individualized, holistic approach that respects personal definitions of recovery (3). The literature suggests that recovery is both a process and an outcome, with symptom remission as only one of many possible directions a personal experience with mental illness can take (4). Research has demonstrated that recovery-oriented services are understood differently depending on the stakeholders involved (5, 6). Individuals with mental illness often refer to recovery as a personal transformative journey (7, 8), clinicians discuss recovery in terms of measurable outcomes (9, 10), and decision-makers reference recovery as a vision or guiding philosophy (1). These variations in priorities highlight the lack of common emphasis surrounding recovery as an approach to care, which allows for lack of consistency in the delivery.

The recovery journey is often described as facilitated by a collection of qualities, including holistic, non-linear, and strengths-based, among many others (11, 12). Several theoretical models have been developed that outline characteristics identified in the recovery literature. These frameworks are meant to resolve the lack of clarity that existed previously. The current models contain upwards of five (CHIMES) to 10 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, SAMSHA) components, which are further split into related elements, highlighting aspects such as hope, empowerment, and meaning (10, 13). These models, while helpful as theoretical frameworks, present a challenge in their practical implementation by organizations and clinicians due to a gap between what is often a conceptualization (i.e., hope) and pragmatic capabilities. This gap has allowed providers to advertise recovery-oriented services without necessarily describing what such services entail. The term recovery has the potential to be commandeered by various programs in order to relabel traditional approaches to care (3). Variations in interpretations of recovery lead to challenges in creating systematically organized environments that deliver a consistent recovery-oriented approach to care (2, 6).

In the absence of a pragmatic understanding of recovery, the practical applications may be limited based on the attitude and knowledge of the individual service provider (8, 14, 15). The purpose of this scoping study is to identify and map the essential elements that contribute to recovery for individuals living with severe mental illness. In doing so, we endeavor to create a practical framework that will enable mental health professionals to better understand and incorporate these key elements into their strategic efforts to support clients, in an attempt to narrow the current gap in knowledge translation between knowing and doing.

We followed Arksey & O'Malley's scoping review strategy to design and conduct this study (16). This strategy consists of five main steps: (a) identifying the research question, (b) identifying relevant studies, (c) selection of critical articles, (d) reviewing and charting the data, and (e) collating and summarizing the results. This strategy allowed us to identify key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in the research literature by systematically searching and synthesizing existing knowledge to inform mental health care practice. We also incorporated recommendations of Peters and colleagues for systematic scoping review by reporting the operational definition of “population,” “concept,” and “context” of the review, and providing information on search strategy, inclusion criteria, and data synthesis (17).

The following research question guided this systematic scoping study: What are the essential elements that contribute to recovery outcomes for individuals living with severe mental illness? For this study, the population was individuals with severe mental illness. Severe mental illness was defined as “a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities” (18). We defined the concept of recovery as “… a deeply personal, unique process of changing one's attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by illness” [11, p. 15]. The spatial and temporal context for this review is studies from across the globe that are related to the recovery of individuals with severe mental illness and were produced from 1988 (one of the first published articles to reference “Recovery” as a concept) (19).

To identify pertinent journal articles, we developed our search strategy in consultation with a health sciences research librarian. We used seven key databases, including MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL/EBSCO, EMBASE, ProQuest, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar, to locate the relevant literature. The keywords used to identify relevant studies are presented in Box 1. Please note that these keywords varied to some extent depending on the different indexing schemes of respective databases. The search was conducted in August 2018 and last updated in February 2020.

BOX 1. Search terms.

(severe mental illness OR chronic mental illness OR serious mental illness OR persistent mental illness OR psychosis OR schizophrenia OR bipolar disorder OR depression OR personality disorder OR trauma disorders OR anxiety) AND (recovery OR psychosocial rehabilitation OR psychiatric rehabilitation) AND (theor$ OR framework OR model OR dimension OR paradigm OR concept$ OR frame of reference OR approaches OR oriented services OR oriented interventions OR themes OR processes OR outcomes)

We applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to the studies that emerged in the initial search, as documented in Table 1. We followed a two-stage screening process to select studies that matched our objective. The first stage involved reading the titles and abstracts, and the second stage included reading the full-text articles. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts, and the selected articles were divided within the research team for full-text review. Any discrepancies were resolved during the monthly consultation meetings of the research team. The final list of articles was compiled into an MS–Excel file/spreadsheet for data charting. The information on a number of sources identified, screened, found eligible, and finally included in the study is presented in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). The PRISMA 2009 checklist can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart. SMI, Severe mental illness. Source: (20).

The descriptors used for data charting included authors, journal title, time and location of the study, study design, study population, sample size, the purpose of the study, key outcomes or results, and any other data relevant to our study objectives. The descriptor “not available” was used if any of the required information was missing from the source. All the authors completed data charting in the spreadsheet.

After data charting was completed, the research team prepared a descriptive numerical summary and conducted a qualitative thematic analysis to present the key findings of the study. A summary of descriptive findings was collated from the spreadsheet, and each team member coded them independently using Braun and Clarke principles of thematic analysis (21). Later, all team members listed their codes and similar codes were clustered to key themes inductively in two consecutive team meetings. Details on study design, study population, sample size, time and location, and purpose of the study are given in the form of numerical summary, while critical results and outcomes are reported in the way of thematic synthesis. We are reporting this study using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (22).

Out of 4,496 sources identified, 601 references were extracted from seven bibliographic databases. Sixty (n = 60) sources were finally accepted that met all the selection criteria.

Of the 60 sources that were included in the final review, the majority were empirical, comprising qualitative studies (n = 32), followed by quantitative (n = 21), and mixed methods (n = 3). The non-empirical records were primarily literature reviews (n = 4). The records presenting empirical research covered a broad spectrum of methodologies (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, and mixed), designs (e.g., longitudinal, cross-sectional, randomized controlled trial, systematic reviews, and case study) and data collection strategies (e.g., interviews, focus groups, ethnographic observations, and surveys). Table 2 provides details on study location, study type, participant population, sample size, and study focus.

Almost all of the sources stemmed from high-income countries. Many studies were conducted in the continent of North America (n = 25) [United States of America (n = 16) and Canada (n = 9)], Europe (n = 16), Australia (n = 7), and the United Kingdom (n = 7) followed by two studies from Israel, one from India, one from South Korea, and one from China. Just under half of the included articles (n = 27, 45%) were published before 2010 (1999–2010), while 55% (n = 33) were published after 2010 (2011–2019). Forty-seven percent of included studies (n = 28) were published within the last 5 years.

Of the total studies, 42% focused broadly on severe mental disorders (n = 25). Most did not specifically mention individual diagnoses to protect the privacy of their participants. A number of sources (32%) focused on or had participants diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum disorders (n = 18), followed by depression (n = 5), psychosis (n = 9), and bipolar disorders (n = 5). Of the 60 studies included, 95% of studies (n = 57) included direct perspectives of individuals with severe mental illness, while three studies focused on the caregiver, expert, and staff experiences, respectively.

The majority of studies (n = 33, 55%) focused broadly on meaning, elements, or aspects of recovery for individuals with severe mental disorders. Some studies (n = 20, 33%) focused on the relevance of specific elements such as hope, resilience, self-efficacy, spirituality, social support, race/ethnicity etc. and their association with the processes underpinning recovery. A few studies (n = 8, 13%) examined various aspects of treatment approaches directed toward recovery.

Through qualitative analysis of the data (see Methods section), the research team developed consensus on the three main elements contributing to recovery from severe mental illness: relationships, sense of meaning, and participation (Figure 2). The research team also reached a consensus on eight sub-elements within these three core elements. Each of the elements and sub-elements is discussed here:

A number of studies (n = 41, 68%) highlighted the importance of supportive relationships in facilitating recovery from severe mental illness. Our analysis generated three relationship subthemes: therapeutic relationships, relationships with significant others, and relationships with the broader community. Please note that these three categories were not mutually exclusive, and each had substantial overlaps.

Several studies included in our review (n = 17, 27%) reported that relationships with service providers impacted the experience and extent of recovery in individuals with severe mental illness (25, 28, 35, 37, 54, 69, 73, 76, 82). Individuals perceived therapeutic relationships, characterized by human qualities such as an attitude of equality, acceptance, empathy, respect, compassion, connection, collaboration, safety and confidence, as helpful in their recovery from schizophrenia (28, 59, 64, 75, 83). Studies also emphasized the role of the therapeutic relationship in kindling and sustaining hope as one of the major factors contributing to full recovery for persons diagnosed with severe mental illness (32, 75). In one model of recovery, clients considered strong and trusting relationships (between service providers, themselves, and their families) that supported their navigation of the mental health system, as essential to their improved mental health (29). Similarly, participants from another study described relationships with clinicians as more facilitative of recovery than the treatment being offered (67). For men, the perceived expertise of the professional and a sense of reciprocity were most important, while for women, trust, listening, and emotional support were more facilitative of recovery (67).

Several studies (n = 10, 16%) found that reconnecting with family and friends was integral to the process of recovery for individuals with severe mental illness (33, 34, 43, 74). One study described the fostering of relationships, facilitated by opportunities to interact with others, develop social skills, and reduce isolation through building social networks, as a core mechanism of recovery (64). In a study involving individuals with depression, participants identified that remaining socially engaged with friends, family, and colleagues, who were informed of the impact of their experience of depression, was key to obtaining the support needed for recovery (78). Similarly, a few studies identified supportive family members or caregivers, who encouraged and positively reinforced the incremental progress of the individual, and were involved as per the choice of the individual, as a critical factor in long-term recovery outcomes for people with schizophrenia (23, 52). A study comparing support from friends and family found that support from friends or others outside of the family network may facilitate recovery from depression more than support from family, as participants' perceived family members as obligated to provide support (58). Thus, perceptions of support from friends or family may influence the recovery process differently (58). Another study found an association between interpersonal relationships, characterized by secure attachment, and participants' levels of hope and self-esteem, suggesting that secure attachments are related to recovery (62).

The research team identified one's relationship with the broader community as the third type of relationship critical to recovery from mental illness, as reported in 25% of the included studies (n = 15) (35, 40, 43, 54, 78, 81). Two studies described recovery as an interactive social journey, involving meaningful, inclusive social relationships, within which individuals exercise rights, encounter opportunities, and receive responses that either support or fail to support their social needs (54, 81). This study described peer support as a bridge toward social opportunities within the wider community and identified the sense of fellowship peer support provides as supportive of recovery (64). Other studies similarly identified peer relationships as key to supporting recovery (61, 72). Many studies described connecting to others, social functioning, and social relationships as important for recovering “coherence,” reducing isolation, making meaning of experiences, and instilling hope (35, 58, 62, 82). One study, involving a group rehabilitation program, described a sense of belonging, or security, acceptance, and connection to others that fosters a feeling that one is a part of a stigma-free community as a mechanism of recovery (64). Another study similarly identified stigma as a factor that impeded recovery through interfering with social inclusion in the community (72).

Majority (n = 49, 82%) of the included studies described a sense of meaning as a facilitator of recovery from severe mental illness. During the qualitative synthesis stage, the research team divided a sense of meaning into three key elements: sense of self, hope, and purpose.

Just under one-third (n = 18, 30%) of the included studies identified a “sense of self” as making an important contribution to recovery. However, each of these studies defined and examined “sense of self” differently. For example, one study involving individuals with severe mental illness (n = 107), suggested that enhancing a positive, clear, non-stigmatizing sense of self may lead to a positive recovery process (39). In a study that examined the experience of recovery from psychosis, recovery was seen as non-linear, occurring in stages, and encompassing physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual aspects of the person (33). Other studies found that building self-efficacy, self-sufficiency, self-acceptance, and reducing self-stigma was a critical recovery mechanism that involved helping individuals gain skills and feel more capable of, and confident in, acting independently and participating in society (31, 32, 40, 46, 64, 70, 79, 81, 84).

Studies seeking individuals' perspectives on recovery from severe mental illness identified personal agency as a key to recovery (41, 72, 78, 79). Factors described as contributing to personal agency included perceived determination to get better, optimism, taking responsibility to help themselves, and understanding, managing, and accepting their illness (41, 44, 72, 79). Another study described self-organization, an ongoing process of “self-creation and self-repair,” as central to recovery in schizophrenia [(56), p. 273]. Participants from another study identified rebuilding the self through self-awareness and reconciling with the past as one of the important components of recovery (77). Other studies identified the acquisition of skills for daily living and self-management as contributing to recovery outcomes (55, 64).

A number of studies (n = 21, 35%) identified hope as a strong determinant of recovery (24, 26, 34, 40, 41, 43, 48, 77). Included studies conceptualized hope in different ways. Many studies described hope in terms of spirituality. Studies described faith as helping to generate and maintain hope in recovery and as providing comfort throughout the process (56, 75). A quantitative study, involving 99 patients with depression, identified higher spirituality as a stronger predictor of recovery (55). This study defined spirituality as a personal quest for a sense of purpose and meaning of life, rather than as religious affiliation. It identified domains of “wholeness and integration,” “inner peace,” and “hope and optimism” as the strongest contributors to the negative association between spirituality and depression (55). Other authors reported similar findings involving different populations (38, 46, 52, 67, 72, 74). For instance, studies involving a group of individuals diagnosed with psychosis or schizophrenia-spectrum disorders identified hope, along with a sense of self-agency, wellbeing resilience, and strength, as integral components of recovery (26, 30, 32, 38, 46).

Several studies (n = 10, 17%) identified a “sense of purpose” as an element that contributes to recovery (24, 40, 43). Individuals with a severe mental illness described the “sense of purpose,” generated from participating in the running of a clubhouse recovery program and contributing to shared goals, as a mechanism of recovery (64). Another study identified creating a sense of purpose as the most important aspect of recovery (48). This study, along with other studies, suggested that the development of self-esteem, agency, and active participation in life is an empowering process that both creates and is created by a sense of purpose (32, 46, 48, 53, 61). One study described empowerment as a gendered recovery process (67). It found that women described recovery as a process of regaining their “whole” identity, moving from a sense of oneself as the object of treatment to the perception that one is a subject, engaged in, and accepting of, the recovery process [(38), p. 563].

The research team divided participation into two sub-themes: roles and personal agency. Articles grouped within this theme described participation in meaningful roles within one's family and community (roles) and participation in one's life choices (agency) as critical elements contributing to recovery. Just under half (n = 25, 42%) of the included sources identified participation as an important recovery theme, of which 17 studies highlighted roles and eight studies highlighted personal agency.

A number of studies (n = 17, 28%) found certain roles to be associated with recovery from severe mental illness. Several studies described meaningful, helping, or productive roles as positively impacting the recovery journey of patients with severe mental illness (27, 32, 46, 76, 77, 82). Some of these studies explored the different life roles of their participants related to productive work such as employment, parenthood, volunteering, religious practice, or self-care (35, 46, 57, 60, 64, 66, 72, 78, 80). For example, one study found that gaining and maintaining employment was associated with financial stability, increased self-esteem, and empowerment (66). Decreased boredom, associated with employment, was also associated with an increase in meaningful activities, which was, in turn, associated with increased social interaction and feelings of inclusion (66).

A few studies also looked at the interplay of gendered roles, culture, and ethnicity and their influence on recovery (47, 49). A study examining the importance of enabling women to challenge assumptions related to roles, limitations, and rules considered this process as empowering women to make sense of their depression and to construct new lives (68). However, in another study, the authors argued that traditional gender roles advantaged women (67). The authors of this study found that greater acceptance of women as dependent on social supports, such as family, and reduced pressures for women to work and study, actually lessened the burden of role expectations and contributed toward recovery (67). In a qualitative study exploring the relationship between ethnicity, culture, and recovery (n = 47), all the ethnic groups identified progress in employment, social engagement, and community participation as facilitators to recovery while identifying stigma, financial constraints, and psychiatric hospitalization as barriers to recovery (80).

Several studies (n = 8, 13%) identified active agency in one's recovery path, cultivated through opportunities to take an active role in treatment decisions and to choose to use services according to one's wants and needs, as a critical element of recovery from severe mental illness (31, 34, 35, 64, 76). One study referred to the personal agency as “self-directed empowerment” in discussions regarding the recovery of study participants with bipolar disorder (77). In a study on self-management in the recovery from depression, participants found that assuming an active and critical attitude toward the illness and service providers and using self-management strategies in their daily life such as goal setting, activity schedules, to-do lists, and distractions contributed to their recovery (78). In another study, participants shared that autonomous action helped them to become independent citizens rather than subjects of a paternalistic mental health care system (57).

This systematic scoping review aimed to identify and explore the essential elements of recovery to better guide practical clinical interventions. The authors approached this research through a functional lens with a focus on the practical application of theoretical knowledge to better support evidence-informed delivery of care. Previous research has found the boundary between the questions, “what constitutes recovery and what are the factors that enhance it” are blurry [(85), p. 177]. The themes generated in this scoping review represent an ongoing fusion of recovery as a means and an end, suggesting that recovery can be promoted through enhancing relationships, sense of meaning, and participation, and also be measured through the presence of each of these elements in our lives.

It is noteworthy that most of the literature included qualitative studies conducted with individuals with severe mental illness belonging to North American countries. Within the studies included, schizophrenic disorders were dominantly represented, with only a few studies focusing on depression, which is among the largest single cause of disability worldwide (83). Similarly, only a few studies included the perspectives of informal caregivers/support persons or professionals working with clients with severe mental illness (24, 42). These findings point to the fact that while there has been an increase in the effort to understand recovery from client perspectives, there remains a need to incorporate the diversity in perspectives and socio-demographic needs of those living with a broader spectrum of severe mental illness and those offering support.

The research team acknowledges that recovery is a deeply personal and unique journey for each individual, which implies that each person may have their own definition of what recovery entails for them [(12), p. 1250]. Despite the personal nature of recovery, previous research has identified several elements commonly cited in the literature as influential to recovery. Our findings on recovery compliment and simplify recovery components discussed in this research, including those described in a recent systematic review specific to recovery and mental illness (2). Our research team grouped common elements found in the literature into three pillars: relationships, sense of self, and participation. The significance of each pillar and its respective components allow for infinite variation in the recovery journey while providing clinicians with a practical approach to supporting those individuals. These pillars and elements do not represent an exhaustive list but are consistent themes throughout the literature and can offer clinicians guidance in translating recovery theory into practice.

Keeping the three pillars in the forefront of the clinical practice, while allowing the client to define their specific recovery journey, may provide clinicians with a pragmatic approach to better facilitate client recovery. This research team also feels that the simplistic approach of the three pillars (relationships, participation, and sense of self) to this complex topic will enable dynamic discussions on this issue with clients, support members and also with policymakers. Demonstrating a clear need to create an environmental shift through policy to better support personal recovery through the utilization of pragmatic relatable terms may help to move the recovery model forward regardless of objective outcome measures.

The nature of recovery is unique and often ambiguous, which presents an ongoing challenge to clinicians on how to best facilitate/support the recovery process. System-level policies and funding models emphasize measurable outcomes, but the personal recovery journey does not always lend itself to measurable change. This sanctions the traditional paternalistic approach in which clinicians and family members are seeking symptom remission despite what the recovery literature suggests that the client is not necessarily focused on remission. The traditional approach is symptom remission through medication in order to permit participation, engage in relationships and deepen one's sense of self. Perhaps if the focus is weighted more heavily on the pillars of recovery, symptom reduction would be the outcome. To challenge this traditional approach would also require environmental/system-level changes to allow for appropriate supports to be available without the necessity of traditional outcome measures.

Underemphasized, in the included articles, was the role that environmental interventions could play in recovery. This predominant focus on person-level elements has likewise been noted in a recent systematic review and could be explained, in part, by accepted definitions of recovery that do not explicitly reference the environment as a site of change (2, 7, 11, 19). Despite the tendency in clinical practice to direct service toward the individual, a growing body of research shows that the environment is often more immediately amenable to change than the person (86–90). The WHO's Commission on the Social Determinants of Mental Health supports the role of the environment in promoting recovery, arguing that mental health is shaped “to a great extent by the social, economic, and physical environments in which people live” [(91), p. 8]. Many models, such as the WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), the Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO), the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E), and Ecology of Human Performance, also recognize the environment as a valid and consequential site for recovery-oriented intervention (92). Though treating the environment as an agent of change is becoming more common in policy and public health initiatives seeking to create recovery opportunities for clients, such as Housing First and Individual Placement and Support (93, 94), access to these services is often limited (3). This scoping review reinforces that essential elements of recovery must be identified through a broader lens that considers the role of micro, meso, and macro layers of the environment in effecting change and achieving optimal recovery outcomes (95).

Through the examined literature, it has become clear that the majority of research exploring recovery-oriented practice has been completed using a client-centered approach (5, 96). The paradigm of client-centered mental health care is becoming more widely used and accepted amongst clinicians and researchers (50, 97). Future research using qualitative and quantitative methods must be employed to improve our understanding of recovery from perspectives of family, caregivers, and clinicians. The role of environmental and social factors must also be more carefully considered in future research to facilitate its integration into the design of recovery-oriented interventions. Through further research and continued consideration of the many elements of recovery, clinicians will be better able to engage in meaningful and beneficial recovery-oriented practice (1). Furthermore, critical research into the concept of recovery itself may reinforce the need for substantive restructuring of systems that claim to promote recovery, expanding the focus from the individual to consider cooperative, collective, and systems-level approaches to recovery [(98), p. 145, (99)].

As our search strategy was limited to articles in English, we did not consider articles written in other languages. We also limited the selection of articles to electronic databases and peer-reviewed journal articles available at Queen's University Health Science Library. It is possible that the strategy and inclusion criteria may have limited the number of studies found to be appropriate for the review. We attempted to be comprehensive in our search by employing several strategies: (1) including articles from 1988 (first reference of recovery concept); (2) conducting searches in Google and the six most relevant electronic databases for peer-reviewed articles on recovery and mental health; and (3) consulting a health science librarian and incorporating her input on keywords and search strategy. We also acknowledge that our research team's composition of occupational therapists providing mental health rehabilitation care may have influenced our analysis. Although the team includes one group of stakeholders (occupational therapists seeking to implement recovery-oriented interventions), we could not consult with other key stakeholders (service users and community partners) to validate themes generated, and so did not fully include the sixth stage of scoping review methodology recommended by Levac et al. (100). Engaging clients, family members, caregivers, other mental health professionals or researchers in reviewing this paper and the identified components would have been advantageous. Seeking out explicit feedback through focus groups could identify new ideas or gaps in the paper that could guide future research.

This scoping review documents important knowledge translation gaps in the literature on recovery elements and identifies a critical need for future studies to address this issue. Our review identified relationships, sense of meaning, and participation as the three major pillars key to recovery for persons with severe mental illness. This review revealed a number of gaps, which may inform future research: (1) lack of standardized elements for conceptualizing recovery for persons with severe mental illness; (2) need to incorporate diversity in perspectives and socio-demographic needs of those with severe mental illness; (3) lack of emphasis on the role of the environment in influencing the process and outcome of recovery. Further research and continued emphasis on the application of the core elements of recovery will facilitate clinicians' engagement in meaningful and effective recovery-oriented practice.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

AJ and KC contributed to the conception and design of the study. AJ and SG reviewed the title and abstracts of all the articles found during the initial search. All authors were involved equally in screening the articles using inclusion and exclusion criteria, extracting the information for data charting, qualitative data synthesis, and writing the first draft of the manuscript. SG prepared the numerical summary and tables. PC, TS, SG, KC, and AJ edited the final manuscript for submission. All authors read and approved the submitted version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors acknowledged the support received from the Providence Care Community Mental Health Services for this project work. We also thanked Karen Gagnon, Health Sciences Librarian at the Providence Care Hospital and Queen's University, for her guidance on developing the search strategy. We would also like to thank Alison Best, Elly Mechefske, Jennifer Pritchett, Karen Gagnon, Rachelle Hill, and Simona Sanislav for their assistance with the article screening process.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586230/full#supplementary-material

1. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Guidelines for Recovery Oriented Practice. Ottawa, ON: Mental Health Commission of Canada (2015).

2. Ellison ML, Belanger LK, Niles BL, Evans LC, Bauer MS. Explication and definition of mental health recovery: a systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. (2018) 45:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0767-9

3. Drake RE, Whitley R. Recovery and severe mental illness: description and analysis. Can J Psychiatry. (2014) 59:236–42. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900502

4. Whitley R, Palmer V, Gunn J. Recovery from severe mental illness. CMAJ. (2015) 187:951–2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141558

5. Lal S. Prescribing recovery as the new mantra for mental health: does one prescription serve all? Can J Occup Ther. (2010) 77:82–9. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2010.77.2.4

6. Leamy M, Clarke E, Le Boutillier C, Bird V, Choudhury R, MacPherson R, et al. Recovery practice in community mental health teams: national survey. Br J Psychiatry. (2016) 209:340–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160739

7. Deegan P. Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (1996) 19:91–7. doi: 10.1037/h0101301

8. Piat M, Lal S. Service providers' experiences and perspectives on recovery-oriented mental health system reform. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2012) 35:289–96. doi: 10.2975/35.4.2012.289.296

9. Mausbach BT, Moore R, Bowie C, Cardenas V, Patterson TL. A Review of instruments for measuring functional recovery in those diagnosed with psychosis. Schizophr Bull. (2009) 35:307–18. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn152

10. Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry. (2011) 199:445–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

11. Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J. (1993) 16:11–23. doi: 10.1037/h0095655

12. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA's 1237 Working Definition of Recovery. Rockville, VA: SAMHSA (2012).

13. Whitley R, Drake RE. Recovery: a dimensional approach. Psychiatr Serv. (2010) 61:1248–50. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.12.1248

15. Dickerson FB. Disquieting aspects of the recovery paradigm. Psychiatr Serv. (2006) 57:647. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.5.647

16. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

17. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13:141–6. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

18. The National Insitute of Mental Health. Mental Illness. (2019). p. 1–8. Available online at: www.nimh.nih.gov (accessed January 24, 2020).

19. Deegan P. Recovery: the lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosoc Rehabil J. (1988) 11:11–9. doi: 10.1037/h0099565

20. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ. (2009) 339:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

21. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

22. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA-ScR checklist items. Ann Intern Med. (2019) 11–2. Available online at: http://www.prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA-ScR Fillable Checklist.pdf%0A (accessed January 29, 2020).

23. Aldersey HM, Whitley R. Family influence in recovery from severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J. (2015) 51:467–76. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9783-y

24. Andresen R, Oades L, Caputi P. The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2003) 37:586–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01234.x

25. Anthony KH. Helping partnerships that facilitate recovery from severe mental illness. J Psychosoc Nurs. (2008) 46:24–35. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20080701-01

26. Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, Lysaker PH, Minor KS, Salyers MP. Language and hope in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 245:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.013

27. Bonfils KA, Adams EL, Firmin RL, White LM, Salyers MP. Parenthood and severe mental illness: relationships with recovery. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2014) 37:186–93. doi: 10.1037/prj0000072

28. Borg M, Kristiansen K. Recovery-oriented professionals: helping relationships in mental health services. J Ment Heal. (2004) 13:493–505. doi: 10.1080/09638230400006809

29. Chinman M, Allende M, Bailey P, Maust J, Davidson L. Therapeutic agents of assertive community treatment. Psychiatr Q. (1999) 70:137–62. doi: 10.1023/A:1022101419854

30. Connell M, Schweitzer R, King R. Recovery from first-episode psychosis: a dialogical perspective. Bull Menninger Clin. (2015) 79:70–90. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2015.79.1.70

31. Davidson L, Borg M, Marin I, Topor A, Mezzina R, Sells D. Processes of recovery in serious mental illness: findings from a multinational study. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2005) 8:177–201. doi: 10.1080/15487760500339360

32. Firmin RL, Luther L, Lysaker PH, Salyers MP. Self-initiated helping behaviors and recovery in severe mental illness: implications for work, volunteerism, and peer support. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2015) 38:336–41. doi: 10.1037/prj0000145

33. Forchuk C, Jewell J, Tweedell D, Steinnagel L, Consultant FN, Lianne O. Reconnecting: the client experience of recovery from Psychosis. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2003) 39:141–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2003.00141.x

34. Giusti L, Ussorio D, Tosone A, Di Venanzio C, Bianchini V, Necozione S, et al. Is personal recovery in schizophrenia predicted by low cognitive insight? Community Ment Health J. (2014) 51:30–7. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9767-y

35. Griffiths CA, Heinkel S, Dock B. Enhancing recovery: transition intervention service for return to the community following exit from an alternative to psychiatric inpatient admission – a residential recovery house. J Ment Heal Training Educ Pract. (2015) 10:39–50. doi: 10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2014-0027

36. Gumley A, Macbeth A. A pilot study exploring compassion in narratives of individuals with psychosis: implications for an attachment-based understanding of recovery. Ment Health Relig Cult. (2014) 17:794–811. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2014.922739

37. Hamm JA, Leonhardt BL, Fogley RL, Lysaker PH. Literature as an exploration of the phenomenology of schizophrenia: disorder and recovery in Denis Johnson's Jesus' Son. Med Humanit. (2014) 40:84–9. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2013-010464

38. Hancock N, Smith-Merry J, Jessup G, Wayland S, Kokany A. Understanding the ups and downs of living well: the voices of people experiencing early mental health recovery. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1703-1

39. Hasson-ohayon I, Mashiach M, Lysaker PH, Roe D. Self-clarity and different clusters of insight and self-stigma in mental illness. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 240:308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.060

40. Hasson-ohayon I, Mashiach-eizenberg M, Elhasid N, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH, Roe D. ScienceDirect between self-clarity and recovery in schizophrenia: reducing the self-stigma and finding meaning. Compr Psychiatry. (2014) 55:675–80. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.11.009

41. Hoffmann H, Kupper Z. Facilitators of psychosocial recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2002) 14:293–302. doi: 10.1080/0954026021000016932

42. Hungerford C, Richardson F. Operationalising recovery-oriented services: the challenges for carers. Adv Ment Heal. (2013) 12:11–21. doi: 10.5172/jamh.2013.12.1.11

43. Hyde B, Bowles W, Pawar M. “We're still in there” - Consumer voices on mental health inpatient care: social work research highlighting lessons for recovery practice. Br J Soc Work. (2015) 45:62–78. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcv093

44. Jerrell JM, Cousins VC, Roberts KM. Psychometrics of the recovery process inventory. J Behav Heal Serv Res. (2006) 33:464–73. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9031-5

45. Jørgensen R, Zoffmann V, Munk-jørgensen P, Buck KD, Jensen SOW, Hansson L, et al. Relationships over time of subjective and objective elements of recovery in persons with schizophreni. Psychiatry Res. (2015) 228:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.013

46. Jose D, Lalitha K, Gandhi S, Desai G. Consumer perspectives on the concept of recovery in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Asian J Psychiatr. (2018) 14:13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.01.006

47. Kidd SA, Virdee G, Quinn S, McKenzie KJ, Toole L, Krupa T. Racialized women with severe mental illness: an arts-based approach to locating recovery in intersections of power, self-worth, and identity. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2014) 17:20–43. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2013.873371

48. Pitt L, Kilbride M. Researching recovery from psychosis. Ment Heal Pract. (2005) 9:20–3. doi: 10.7748/mhp2006.04.9.7.20.c1906

49. Kwok CFY. Beyond the clinical model of recovery: recovery of a Chinese immigrant woman with bipolar disorder. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. (2014). 24:129–33. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-42953-009

50. Lakeman R. Mental health recovery competencies for mental health workers: a Delphi study. J Ment Heal. (2010) 19:62–74. doi: 10.3109/09638230903469194

51. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2002) 14:256–72. doi: 10.1080/0954026021000016905

52. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A. Recovery from schizophrenia: a challenge for the 21st century. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2002) 14:245–55. doi: 10.1080/0954026021000016897

53. Markowitz F. Modeling processes in recovery from mental illness: relationships between symptoms, life satisfaction, and self-concept. J Heal Soc Behav. (2001) 42:64–79. doi: 10.2307/3090227

54. Mezzina R, Davidson L, Borg M, Marin I, Topor A, Sells D. The social nature of recovery: discussion and implications for practice. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2006) 9:63–80. doi: 10.1080/15487760500339436

55. Mihaljevic S, Aukst-Margetic B, Karnicnik S, Vuksan-Cusa B, Milosevic M. Do spirituality and religiousness differ with regard to personality and recovery from depression? A follow-up study. Compr Psychiatry. (2016) 70:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.06.003

56. Murphy MA. Coping with the spiritual meaning pf psychosis. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2000) 24:179–83. doi: 10.1037/h0095101

57. Myers NL. Culture, stress and recovery from schizophrenia: lessons from the field for global mental health. Cult Med Psychiatry. (2010) 34:500–28. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9186-7

58. Nasser EH, Overholser JC. Recovery from major depression: the role of support from family, friends, and spiritual beliefs. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2005) 111:125–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00423.x

59. O'Keeffe D, Sheridan A, Kelly A, Doyle R, Madigan K, Lawlor E, et al. ‘Recovery' in the real world: service user experiences of mental health service use and recommendations for change 20 years on from a first episode psychosis. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. (2018) 45:635–48. doi: 10.1007/s10488-018-0851-4

60. Ouwehand E, Wong K, Boeije H, Braam A. Revelation, delusion or disillusion: subjective interpretation of religious and spiritual experiences in bipolar disorder. Ment Heal Relig Cult. (2014) 17:615–28. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2013.874410

61. Park SA, Sung KM. The effects on helplessness and recovery of an empowerment program for hospitalized persons with schizophrenia. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2013) 49:110–7. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12002

62. Ringer JM, Buchanan EE, Olesek K, Lysaker PH. Anxious and avoidant attachment styles and indicators of recovery in schizophrenia: associations with self-esteem and hope. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. (2014) 87:209–21. doi: 10.1111/papt.12012

63. Rosa AR, González-Ortega I, González-Pinto A, Echeburúa E, Comes M, Martínez-Àran A, et al. One-year psychosocial functioning in patients in the early vs. late stage of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2012) 125:335–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01830.x

64. Rouse J, Mutschler C, McShane K, Habal-Brosek C. Qualitative participatory evaluation of a psychosocial rehabilitation program for individuals with severe mental illness. Int J Ment Health. (2017) 46:139–56. doi: 10.1080/00207411.2017.1278964

65. Rudnick A. Recovery from schizophrenia: a philosophical framework. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2008) 11:267–78. doi: 10.1080/15487760802186360

66. Sapani J. Recommendations for a “Recovery” orientated apprenticeships scheme in mental health: a literature review. J Ment Heal Training Educ Pract. (2015) 10:180–8. doi: 10.1108/JMHTEP-04-2014-0007

67. Schön UK. Recovery from severe mental illness, a gender perspective. Scand J Caring Sci. (2010) 24:557–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00748.x

68. Schreiber R. Wandering in the dark: women's experiences with depression. Heal Care Woman Int. (2001) 22:85–98. doi: 10.1080/073993301300003090

69. Sells D, Borg M, Marin I, Mezzina R, Topor A, Davidson L. Arenas of recovery for persons with severe mental illness. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2006) 9:3–16. doi: 10.1080/15487760500339402

70. Shahar G, Davidson L, Trower P, Iqbal Z, Birchwood M, Chadwick P. The person in recovery from acute and severe psychosis: the role of dependency, self-criticism, and efficacy. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (2004) 74:480–8. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.480

71. Thomas EC, Salzer MS. Associations between the peer support relationship, service satisfaction and recovery-oriented outcomes: a correlational study. J Ment Heal. (2018) 27:352–8. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1417554

72. Tooth B, Kalyanasundaram V, Glover H, Momenzadah S. Factors consumers identify as important to recovery from schizophrenia. Aust Psychiatry. (2003) 11:70–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1665.11.s1.1.x

73. Topor A, Denhov A. Helping relationships and time: inside the black box of the working alliance. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2012) 15:239–54. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2012.703544

74. Torgalsbøen AK. Consumer satisfaction and attributions of improvement among fully recovered schizophrenics. Scand J Psychol. (2001) 42:33–40. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00212

75. Torgalsbøen AK, Rund BR. Maintenance of recovery from schizophrenia at 20-year follow-up: what happened? Psychiatry. (2010) 73:70–83. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2010.73.1.70

77. Tse S, Murray G, Chung KF, Davidson L, Ng KL, Yu CH. Exploring the recovery concept in bipolar disorder: a decision tree analysis of psychosocial correlates of recovery stages. Bipolar Disord. (2014) 16:366–77. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12153

78. van Grieken RA, Kirkenier ACE, Koeter MWJ, Nabitz UW, Schene AH. Patients' perspective on self-management in the recovery from depression. Heal Expect. (2015) 18:1339–48. doi: 10.1111/hex.12112

79. Warwick H, Tai S, Mansell W. Living the life you want following a diagnosis of bipolar disorder: a grounded theory approach. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2019) 26:362–77. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2358

80. Whitley R. Ethno-racial variation in recovery from severe mental illness: a qualitative comparison. Can J Psychiatry. (2016) 61:340–7. doi: 10.1177/0706743716643740

81. Williams CC, Collins AA. Defining new frameworks for psychosocial intervention. Psychiatry. (1999) 62:61–78. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1999.11024853

82. Wood L, Price J, Morrision A, Haddock G. Exploring service users perceptions of recovery from psychosis: a Q-methodological approach. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. (2013) 86:245–61. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02059.x

83. World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020, Vol. 1429. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013).

84. Mezzina R, Borg M, Marin I, Sells D, Topor A, Davidson L. From participation to citizenship: how to regain a role, a status, and a life in the process of recovery. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2006) 9:39–61. doi: 10.1080/15487760500339428

85. van Weeghel J, van Zelst C, Boertien D, Hasson-Ohayon I. Conceptualizations, assessments, and implications of personal recovery in mental illness: a scoping review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2019) 42:169–81. doi: 10.1037/prj0000356

86. Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Gray DB, Stark S, Kisala P, et al. Environmental barriers and supports to everyday participation: a qualitative insider perspective from people with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2015) 96:578–88. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.008

87. Harrison M, Angarola R, Forsyth K, Irvine L. Defining the environment to support occupational therapy intervention in mental health practice. Br J Occup Ther. (2016) 79:57–9. doi: 10.1177/0308022614562787

88. Law M. 1991 Muriel Driver lecture. The environment: a focus for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. (1991) 58:171–80. doi: 10.1177/000841749105800404 Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10170862 (accessed February 11, 2020).

89. Schneidert M, Hurst R, Miller J, Üstün B. The role of environment in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Disabil Rehabil. (2003) 25:588–95. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000137090

90. Wong AWK, Ng S, Dashner J, Baum MC, Hammel J, Magasi S, et al. Relationships between environmental factors and participation in adults with traumatic brain injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional multi-center study. Qual Life Res. (2017) 26:2633–45. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1586-5

91. World Health Organization and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social Determinants of Mental Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2014).

92. McColl MA, Law MC, Stewart D. The Theoretical Basis of Occupational Therapy. 3rd ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated (2015).

93. Greenwood RM, Stefancic A, Tsemberis S. Pathways housing first for homeless persons with psychiatric disabilities: program innovation, research, and advocacy. J Soc Issues. (2013) 69:645–63. doi: 10.1111/josi.12034

94. Bejerholm U, Areberg C, Hofgren C, Sandlund M, Rinaldi M. Individual placement and support in sweden-a randomized controlled trial. Nord J Psychiatry. (2015) 69:57–66. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.929739

95. Eriksson M, Ghazinour M, Hammarström A. Different uses of Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory in public mental health research: what is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Soc Theory Heal. (2018) 16:414–33. doi: 10.1057/s41285-018-0065-6

96. Onken S, Dumont J. Mental health recovery: what helps and what hinders? A national research project for the development of recovery facilitating system performance indicators. Heal Progr. (2002) 161–2. Available online at: http://www.mhcc.org.au/TICP/research-papers/NASMHPD-NTAC-2002.pdf (accessed Februray 23, 2020).

97. Morrow M, Weisser J. Towards a social justice framework of mental health recovery. Stud Soc Justice. (2013) 6:27–43. doi: 10.26522/ssj.v6i1.1067

98. Hammel KRW. Engagement in Living: Critical Perspectives on Occupation, Rights, and Wellbeing. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (2020). p. 1–253.

99. Castillo EG, Chung B, Bromley E, Kataoka SH, Braslow JT, Essock SM, et al. Community, public policy, and recovery from mental illness: emerging research and initiatives. Harv Rev Psychiatry. (2018) 26:70–81. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000178

Keywords: recovery, rehabilitation, scoping review, elements, mental health, severe mental illness (SMI), outcome, clinical practice

Citation: Jaiswal A, Carmichael K, Gupta S, Siemens T, Crowley P, Carlsson A, Unsworth G, Landry T and Brown N (2020) Essential Elements That Contribute to the Recovery of Persons With Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Scoping Study. Front. Psychiatry 11:586230. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586230

Received: 22 July 2020; Accepted: 23 September 2020;

Published: 19 November 2020.

Edited by:

Helen Killaspy, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Shulamit Ramon, University of Hertfordshire, United KingdomCopyright © 2020 Jaiswal, Carmichael, Gupta, Siemens, Crowley, Carlsson, Unsworth, Landry and Brown. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Atul Jaiswal, YXR1bC5qYWlzd2FsQHVtb250cmVhbC5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.