95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 09 December 2020

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569083

Bella Nichole Kantor1,2

Bella Nichole Kantor1,2 Jonathan Kantor2,3,4,5,6*

Jonathan Kantor2,3,4,5,6*Pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may lead to significant mental health stresses, potentially with modifiable risk factors. We performed an internet-based cross-sectional survey of an age-, sex-, and race-stratified representative sample from the US general population. Degrees of anxiety, depression, and loneliness were assessed using the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7), the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, and the 8-item UCLA Loneliness Scale, respectively. Unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine associations with baseline demographic characteristics. A total of 1,005 finished surveys were returned of the 1,020 started, yielding a completion rate of 98.5% in the survey panel. The mean (standard deviation) age of the respondents was 45 (16) years, and 494 (48.8%) were male. Overall, 264 subjects (26.8%) met the criteria for an anxiety disorder based on a GAD-7 cutoff of 10; a cutoff of 7 yielded 416 subjects (41.4%), meeting the clinical criteria for anxiety. On multivariable analysis, male sex (odds ratio [OR] = 0.65, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.49, 0.87]), identification as Black (OR = 0.49, 95% CI [0.31, 0.77]), and living in a larger home (OR = 0.46, 95% CI [0.24, 0.88]) were associated with a decreased odds of meeting the anxiety criteria. Rural location (OR 1.39, 95% CI [1.03, 1.89]), loneliness (OR 4.92, 95% CI [3.18, 7.62]), and history of hospitalization (OR = 2.04, 95% CI [1.38, 3.03]) were associated with increased odds of meeting the anxiety criteria. Two hundred thirty-two subjects (23.6%) met the criteria for clinical depression. On multivariable analysis, male sex (OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.53, 0.95]), identifying as Black (OR = 0.62, 95% CI [0.40, 0.97]), increased time outdoors (OR = 0.51, 95% CI [0.29, 0.92]), and living in a larger home (OR = 0.35, 95% CI [0.18, 0.69]) were associated with decreased odds of meeting depression criteria. Having lost a job (OR = 1.64, 95% CI [1.05, 2.54]), loneliness (OR = 10.42, 95% CI [6.26, 17.36]), and history of hospitalization (OR = 2.42, 95% CI [1.62, 3.62]) were associated with an increased odds of meeting depression criteria. Income, media consumption, and religiosity were not associated with mental health outcomes. Anxiety and depression are common in the US general population in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and are associated with potentially modifiable factors.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to unprecedented levels of movement restriction, job losses, and economic uncertainty in the United States and around the world (1). Concerns regarding illness, death, and the death of loved ones may be compounded by financial uncertainty, as reports of mass unemployment with variable international governmental responses circulate (2).

Mental health outcomes have been associated with pandemics in the past (3–5). While there has been a rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of nonpharmaceutical interventions, vaccine development, and medical support, little comprehensive planning has been performed to predict and respond to the possible mental health crisis that could emerge from the pandemic, and the only data available on general public responses to the pandemic are in Chinese populations (6, 7). A recent study in the UK population included a set of two surveys of the general public, although their focus was on prioritization of concerns rather than estimating the prevalence of mental health outcomes (8). These data are echoed by research suggesting that healthcare workers have a significant burden of mental health challenges in the face of COVID-19 and highlighting the potential psychological effects of quarantine (9, 10). Moreover, pandemics and other natural disasters may disproportionately affect those with underlying mental illness, the elderly, and healthcare workers (11–14). Loneliness can be exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic through several mechanisms and may be associated with other mental health outcomes (15, 16). Time spent outdoors may also be associated with better mental health in the pandemic context, particularly if this time is spent exercising, a benefit that may be more pronounced for women than men (17). Time spent outdoors in general may also be associated with improved positive affect and decreased negative emotions based on a UK study (18). A recent position paper issued a call to action for high-quality population-level data to assess the mental health burden in the context of the present pandemic (8), and it is possible that the uptake of nonpharmaceutical interventions is affected by mental health outcomes given the role of behavioral considerations in their implementation (19, 20).

We therefore sought to investigate the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the general US population in the context of the early COVID-19 pandemic and explore associations of these mental health outcomes with loneliness (of particular concern given enhanced social distancing and isolation), health status, socioeconomic status, residence size, time spent outdoors, and other baseline demographic characteristics. These baseline characteristics were chosen given their potential relevance for developing future risk models and their potential modifiability. A better understanding of the prevalence of these mental health outcomes and their putative risk factors may help guide public policy, research, and interventions.

This study is a cross-sectional, internet-based survey performed via age, sex, and race stratification to reflect the makeup of the general US population, conducted between March 29, 2020, and March 31, 2020. Responses to all survey questions were recorded (Supplemental file). This study was deemed exempt by the Ascension Health institutional review board.

We developed an online survey using the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics Corp., Provo, UT) after iterative online pilot testing. The survey was distributed to a representative sample of the US population using Prolific Academic (Oxford, United Kingdom), an established platform for academic survey research (21). Prolific Academic maintains a database of possible survey respondents and distributes surveys using a survey panel approach. Respondents were rewarded with a small payment (<US $1). Participants provided consent and were permitted to terminate the survey at any time. All surveys were anonymous and confidential, with linkages between data performed using a 24-character alphanumeric code. The investigators had no access to identifying information at any time.

This internet-based survey was stratified by age, sex, and race to reflect the makeup of the general US population. Sample size calculations were conducted for the primary endpoint of detecting a 10% difference in the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7) between those that were and were not under a stay-at-home order at the time of survey completion. Six hundred eighty-two subjects (341 per group) would be adequate to detect a 10% change in GAD-7 with 80% power and with an α of 0.05, assuming a baseline GAD-7 mean of 11.6 with a standard deviation (SD) of 5.4 and assuming equal group sizes (22). We inflated our sample size to 1,000, given that approximately two-thirds of the United States was under stay-at-home orders at the time of survey initiation and given uncertainty regarding changes in those orders over the duration of the survey, as well as to permit subgroup analyses.

For our main outcome measures, anxiety and depression, validated scales were used. Anxiety was assessed using the GAD-7, a validated self-report scale for anxiety, with scores ranging from 0 (no anxiety) to 21 (extreme anxiety). Prior psychometric research suggested cutoffs as 0–4 (no anxiety), 5–9 (mild anxiety), 10–14 (moderate anxiety), and 15–21 (severe anxiety) (9, 22).

Depression was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a validated measure for clinical depression (23). Scores range from 0 (no depression) to 27 (severe depression). Prior psychometric research has suggested cutoffs as 0–4 (no depression), 5–9 (mild depression), 10–14 (moderate depression), and 15–27 (severe depression) (9, 24).

Loneliness was quantified with the UCLA Short-Form Loneliness Scale (ULS-8), a validated measure of loneliness (25). Scores range from 8 (no loneliness) to 32 (extreme loneliness); no clinically meaningful cutoffs have been established psychometrically.

Age, sex, rural area residence, and race were included based on self-report. Binary choices were provided for sex selection. Race was divided into six categories: White, Black/African American, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and other. Religiosity was defined based on self-report of whether the participant considered themselves a religious person, including an ambivalent option. Media consumption was assessed by the number of hours spent watching or reading about the pandemic over the preceding 3 days. Time spent outdoors was measured by self-report on number of hours spent outside over the preceding 3 days, with options for 0, <1, 1–3, 3–5, and more than 5. Income was based on self-report using a range of 12 options from <$10,000 per year to more than $150,000 per year. Home size was based on self-report, with options ranging from <500 square feet to more than 2,000 square feet.

Normally distributed baseline demographic data are presented as mean values with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Outcomes that were not normally distributed are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). t Tests and χ2 tests were used as appropriate for baseline continuous and categorical variables. Subgroup comparisons of non–normally distributed data were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Unadjusted and multivariable (adjusting for the nonmodifiable variables of age and sex) logistic regression odds ratios (ORs) of association were assessed between the dependent variables of anxiety or depression, presented as dichotomous outcomes using the established cutoffs of 10 for both the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, and putative risk factors.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13 for Mac (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

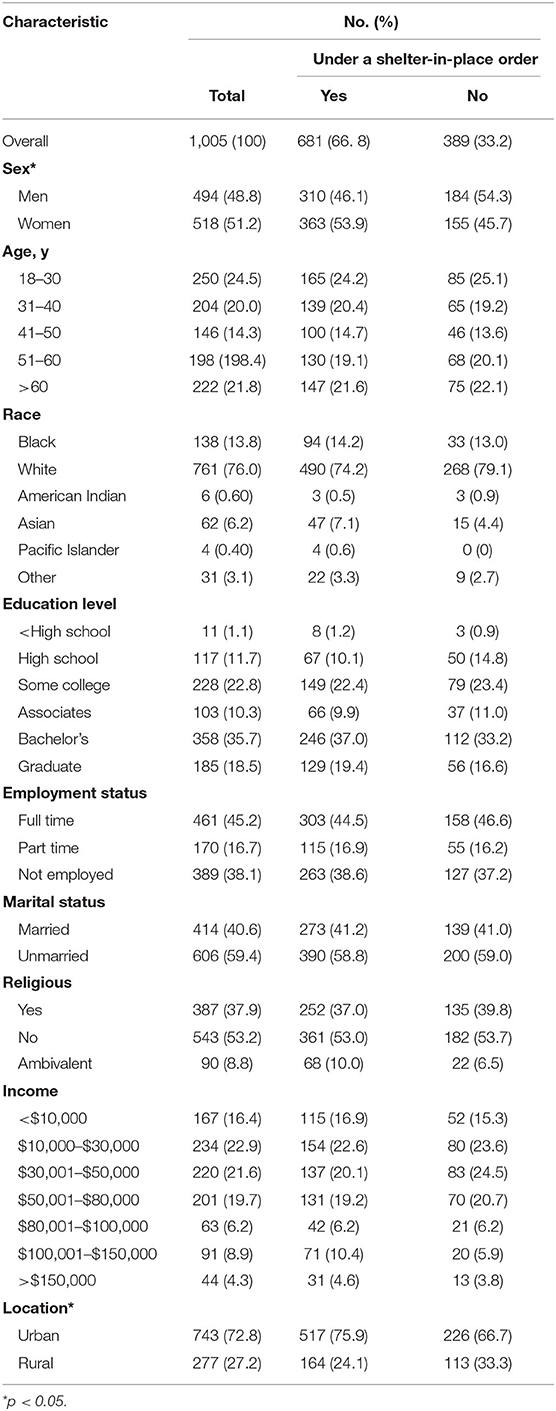

Of the 1,020 subjects who were recruited, 1,005 finished the survey, yielding a completion rate of 98.5%. The mean (SD) age of the respondents was 45 (16) years, and 494 (48.8%) of the respondents were male; baseline respondent characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Baseline demographic data were similar between those that were (n = 663, 66.2%) and were not (n = 339, 33.8%) under a shelter-in-place or stay-at-home order (defined by self-report), with the exception of sex and geographic location (urban vs. rural status). The median (IQR) ULS-8 score for loneliness was 16 (12–20), similar to baseline estimates from previous studies (25–27).

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of respondents, overall, and by shelter-in-place status.

The median (IQR) GAD-7 score was 5 (1–10), and 513 subjects (52.1%) of the subjects had at least mild anxiety. Median GAD-7 scores did not differ significantly by shelter-in-place order status (p = 0.128). Overall, 264 subjects (26.8%) met the criteria for an anxiety disorder based on a GAD-7 cutoff of 10 (Table 2). Adopting a more liberal GAD-7 cutoff of 7, as used in a recent study on healthcare worker anxiety in the COVID-19 context (9), would yield 416 subjects (41.4%) meeting the clinical criteria for anxiety. Women (p = 0.002) and those living in rural areas (p = 0.041) reported more severe anxiety than men and those in urban areas, respectively.

Unadjusted logistic regression analysis demonstrated that men (OR = 0.67, 95% CI [0.51, 0.89]) and those who identified as Black (OR = 0.63, 95% CI [0.40, 0.97]) were less likely to meet the criteria for anxiety, whereas, those who lost their job (OR = 1.61, 95% CI [1.45, 2.45]), had been hospitalized within the past 2 years (OR = 1.86, 95% CI [1.27, 2.73]), or were in the most lonely quartile (OR = 5.39, 95% CI [3.53, 8.24]) were more likely to meet the criteria for anxiety. On multivariable analysis controlling for age and sex as confounders, male sex (OR = 0.65, 95% CI [0.49, 0.87]), identifying as Black (OR = 0.49, 95% CI [0.31, 0.77]), and living in a larger home (OR = 0.46, 95% CI [0.24, 0.88]) were associated with a decreased odds of meeting the anxiety criteria. Rural location (OR = 1.39, 95% CI [1.03, 1.89]), loneliness (OR = 4.92, 95% CI [3.18, 7.62]), and history of hospitalization within the past 2 years (OR = 2.04, 95% CI [1.38, 3.03]) were independent risk factors for meeting the anxiety criteria (Table 3). In a fully adjusted model including all variables that demonstrated p > 0.10 on univariable analyses, identifying as Asian (OR = 0.28, 95% CI [0.10, 0.79]), male sex (OR = 0.59, 95% CI [0.38, 0.94]), and having a larger home size (OR = 0.14, 95% CI [0.04, 0.42] for homes larger than 2,000 square feet) were associated with a decreased odds of meeting the anxiety criteria. Loneliness (OR = 5.05, 95% CI [2.90, 8.78]) was associated with an increased odds of meeting the anxiety criteria in the fully adjusted model.

The median (IQR) PHQ-9 score was 4 (1–9), and 465 (47.3%) of the subjects reported at least mild depression by screening (Table 2). Median PHQ-9 scores did not differ significantly by shelter-in-place order status (p = 0.743). A total of 232 subjects (23.6%) met the criteria for clinical depression. Women (p = 0.008) and unmarried subjects (p < 0.0001) reported more severe depression than men and those who are married, respectively.

Unadjusted logistic regression analysis demonstrated that men were less likely to meet the criteria for depression (OR = 0.73, 95% CI [0.55, 0.98]), whereas those who lost their job (OR = 1.74, 95% CI [1.13, 2.67]), had been hospitalized within the past 2 years (OR = 2.16, 95% CI [1.47, 3.17]), or were in the most lonely quartile (OR = 11.90, 95% CI [7.21, 19.65]) were more likely to meet the criteria for depression. On multivariable analysis controlling for age and sex as confounders, male sex (OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.53, 0.95]), identifying as Black (OR = 0.62, 95% CI [0.40, 0.97]), increased time outdoors (OR = 0.51, 95% CI [0.29, 0.92]), and living in a larger home (OR = 0.35, 95% CI [0.18, 0.69]) were associated with a decreased odds of meeting depression criteria. Having lost a job (OR = 1.64, 95% CI [1.05, 2.54]), loneliness (OR = 10.42, 95% CI [6.26, 17.36]), and history of hospitalization within the past 2 years (OR = 2.42, 95% CI [1.62, 3.62]) were associated with meeting depression criteria (Table 3). In a fully adjusted model including all variables that demonstrated p > 0.10 on univariable analyses, identifying as Black (OR = 0.47, 95% CI [0.23, 0.98]), identifying as Asian (OR = 0.32, 95% CI [0.12, 0.85]), increasing age (OR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.96, 1.00]), and spending 5 h or more outside over the past 3 days (OR = 0.36, 95% CI [0.14, 0.91]) were associated with a decreased odds of meeting depression criteria. Loneliness (OR = 9.41, 95% CI [4.99, 17.75]) was associated with an increased odds of meeting depression criteria in the fully adjusted model.

In this first study of general US population mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, we found high baseline levels of both anxiety and depression, independent of living under a shelter-in-place or stay-at-home order. More than half (52.1%) of the respondents had at least mild anxiety, and 47.3% of the subjects had at least mild depressive symptoms. This high burden of mental health concerns in the general population in the pandemic context suggests the need for further study and consideration for intervention. That said, the prevalence of mental health outcomes is fairly high in the US population at baseline, where estimates have suggested the prevalence of anxiety and depression is on the order of 19% and 24%, respectively (28, 29).

We found that respondents who identify as Black were less likely to meet the criteria for anxiety on both univariate and adjusted analyses and less likely to meet the criteria for depression on adjusted analyses. Those who identified as Asian had decreased odds of meeting both anxiety and depression on fully adjusted analyses. This finding suggests the need for further study, although they echo prepandemic research that has suggested a lower prevalence of self-reported anxiety in respondents who identify as Black (30–32). Estimates regarding the prevalence of depression vary, with some studies suggesting a higher prevalence among minorities and others pointing to a lower prevalence among racial minorities (33–36). Further research is needed to determine whether this finding is a result of confounding or chance or is replicable.

Living in a larger home was associated with a reduced risk of both anxiety and depression; this effect was seen despite the lack of any association between anxiety or depression and household income and persisted when including income and number of household members in a multivariable model. Similarly, we found that increased time spent outdoors correlated with a reduction in depression (but not anxiety) risk, and those who spent more than an hour a day outdoors had approximately half the risk of depression as those who spent no time outdoors. This association of depression with time outdoors echoes prior research on associations with time spent outdoors and its impact on mental health (37, 38). Our finding that both larger living space and increased time spent outdoors correlate with a reduction in mental health burden may have actionable implications for public health initiatives and decisions regarding access to outdoor recreation areas during stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders.

History of hospitalization, a rough measure of overall health status, was associated with an increased risk of both anxiety and depression. This effect persisted even when controlling for age and history of anxiety and depression, respectively, suggesting that those with a poorer health status may be at increased risk of adverse mental health outcomes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Media consumption was not associated with the presence of anxiety or depression. Similarly, we did not detect significant associations between likelihood of meeting the criteria for anxiety or depression and household income or religiosity on adjusted multivariable analyses.

Notably, we found that fewer than half of the respondents had no anxiety; that is, more than half of the subjects reported a level of anxiety that would at least be classified as mild. Conversely, 13.4% of the subjects demonstrated severe anxiety, a higher proportion than has been reported even in healthcare workers responding to pandemic COVID-19 (9). Our finding that 23.6% of the subjects met the criteria for depression using the PHQ-9 echoes earlier pooled data that suggested a prevalence of 24.6% for depression using this scale, although this pooled estimate from 44 studies may overestimate the baseline prevalence of depression due to the inherent limitations of the PHQ-9 (29). The heterogeneity of baseline measures of depression as measured by the PHQ-9 has also been reported in assessments of outpatients (39).

Loneliness is an established risk factor for both anxiety and depression (26, 40), and we found an ~5- to 10-fold increase in odds of anxiety and depression, respectively, with being in the highest loneliness quartile. That said, there may be a tautological relationship between loneliness and depression, and this should be considered when evaluating the relationship between these variables (41). As with those living in smaller homes with minimal access to the outdoors, loneliness can be seen as an independent risk factor for anxiety or depression in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study has several limitations. First, as with any survey-based research, its generalizability may be limited. We used Prolific Academic for survey distribution in order to maximize our generalizability to the general US population by using an age-, sex-, and race-stratified survey panel design with a large and validated sampling frame. As with any survey data, however, the sample willing to participate may not fully reflect the population of interest, and stratifying by these variables does not guarantee that the sample population reflects the general population in any other way. Second, our study took place during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, when shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders were only just beginning. If anything, however, this underestimates the prevalence of anxiety and depression as these outcomes would only be expected to increase as restrictions persist and highlights that even the anticipation of such restrictions may present a stressor. Third, as with any survey study, response bias and social desirability bias may play a role, although the anonymous survey design may help mitigate these concerns. Fourth, while our study relied on validated scales wherever possible, some survey questions were the product of pilot testing alone, and therefore their methodology—although consistent with the survey development literature—has not been fully vetted. Fifth, our selection of independent variables was not exhaustive, and other important variables, such as sleep (42), family stress (43), underlying mental health diseases (44), and others, may be important confounders. Finally, and importantly, this cross-sectional study that lacks a comparator group cannot establish causation; therefore, we do not know whether the associations we describe are truly clinical risk factors.

In this first study of mental health outcomes in the US population during the COVID-19 pandemic, we found high rates of depression and anxiety, with the most profound mental health effects in women, those with a history of hospitalization over the past 2 years, those who were most lonely, and those living in smaller homes, and (for depression) those spending the least time outdoors. These findings may be considered in future public health efforts and in developing national and international pandemic responses.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ascension Health IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

BK and JK: study conception, design, writing, statistics. JK: oversight. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

An earlier draft of this manuscript was released on the MedRxiv preprint server (45).

1. Wells CR, Sah P, Moghadas SM, Pandey A, Shoukat A, Wang Y, et al. Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:7504–9. (2020) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002616117

2. Buehler K, Samandari H, Conjeaud O, Webanck L, Serino L, White O. Leadership in the Time of Coronavirus: COVID-19 Response and Implications for Banks. New York, NY: McKinsey Insights (2020).

3. Marshall H, Tooher R, Collins J, Mensah F, Braunack-Mayer A, Street J, et al. Awareness, anxiety, compliance: community perceptions and response to the threat and reality of an influenza pandemic. Am J Infect Control. (2012) 40:270–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.03.015

4. Taha S, Matheson K, Cronin T, Anisman H. Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and anxiety: the case of the 2009. H1N1 pandemic. Br J Health Psychol. (2014) 19:592–605. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12058

5. Wheaton M, Abramowitz J, Berman N, Fabricant L, Olatunji B. Psychological predictors of anxiety in response to the H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic. Cogn Ther Res. (2012) 36:210–8. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9353-3

6. Lu D, Jennifer B. Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerg Infect Dis J. (2020) 26:7. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.202407

7. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:5. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

8. Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:547. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

9. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

10. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. (2020) 395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

11. Druss BG. Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in populations with serious mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:891–2. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0894

12. Yip PSF, Cheung YT, Chau PH, Law YW. The impact of epidemic outbreak: the case of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis. (2010) 31:86. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000015

13. Tsang HWH, Scudds RJ, Chan EYL. Psychosocial impact of SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. (2004) 10:1326. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.040090

14. Leslie AN, Eric JC, Shawn Tracy C, Hadi A-E, Yemisi B, Sagina H, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. Canad Med Assoc J. (2004) 170:793. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031077

15. Banerjee D, Rai M. Social isolation in Covid-19: The impact of loneliness. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2020) 66:525–7. doi: 10.1177/0020764020922269

16. Li LZ, Wang S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 2020:291. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267

17. Colley RC, Bushnik T, Langlois K. Exercise and screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health reports. (2020) 31:3–11. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202000600001-eng

18. Lades LK, Laffan K, Daly M, Delaney L. Daily emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Health Psychol. (2020) 25:902–11. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12450

19. Kantor BN, Kantor J. Non-pharmaceutical interventions for pandemic COVID-19: a cross-sectional investigation of US general public beliefs, attitudes, and actions. Front. Med. (2020) 7:384. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00384

20. Kantor J. Behavioral considerations and impact on personal protective equipment use: early lessons from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Acad Derm. (2020) 82:1087–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.013

21. Peer E, Brandimarte L, Samat S, Acquisti A. Beyond the Turk: alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. J Exp Soc Psychol. (2017) 70:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.006

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Int Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

23. Milette K, Hudson M, Baron M, Thombs BD. Comparison of the PHQ-9 and CES-D depression scales in systemic sclerosis: internal consistency reliability, convergent validity and clinical correlates. Rheumatology. (2010) 49:789–96. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep443

24. Beard C, Hsu KJ, Rifkin LS, Busch AB, Björgvinsson T. Validation of the PHQ-9 in a psychiatric sample. J Affect Disord. (2016) 193:267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.075

25. Hays RD, Dimatteo MR. A short-form measure of loneliness. J Pers Assessm. (1987) 51:69. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6

26. Soh LK, Pang JS. The relationship between living with a spouse and mental health in the elderly population: moderated mediation effects of loneliness and perceived problems. Clin Med Insights. (2019) 2019:10. doi: 10.1177/1179557319876646

27. Wiseman H, Guttfreund DG, Lurie I. Gender differences in loneliness and depression of university students seeking counselling. Br J Guid Counsel. (1995) 23:231–43. doi: 10.1080/03069889500760241

28. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005) 62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

29. Levis B, Benedetti A, Ioannidis JPA, Sun Y, Negeri Z, He C, et al. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: individual participant data meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. (2020) 122:115–28.e111. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.002

30. Asnaani A, Richey JA, Dimaite R, Hinton DE, Hofmann SG. A cross-ethnic comparison of lifetime prevalence rates of anxiety disorders. J Nerv Mental Dis. (2010) 198:551–5. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ea169f

31. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. (2005) 66:1351–61. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n1102

32. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, June RW, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. (2005) 35:1747–59. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069

33. Dunlop DD, Song J, Lyons JS, Manheim LM, Chang RW. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am J Public Health. (2003) 93:1945–52. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.11.1945

34. Bailey RK, Mokonogho J, Kumar A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: current perspectives. Neuropsych Dis Treat. (2019) 15:603–9. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S128584

35. Riolo SA, Nguyen TA, Greden JF, King CA. Prevalence of depression by race/ethnicity: findings from the national health and nutrition examination survey III. Am J Public Health. (2005) 95:998–1000. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047225

36. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorderresults from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). JAMA. (2003) 289:3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095

37. Christensen KM, Holt JM, Wilson JF. The relationship between outdoor recreation and depression among older adults. World Leisure J. (2013) 55:72–82. doi: 10.1080/04419057.2012.759143

38. Wilson JF, Christensen KM. The relationship between outdoor recreation and depression among individuals with disabilities. J Leisure Res. (2012) 44:486–506. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2012.11950275

39. Wang J, Wu X, Lai W, Long E, Zhang X, Li W, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among outpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017173. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017173

40. Domènech-Abella J, Mundó J, Haro JM, Rubio-Valera M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: longitudinal associations from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). J Affect Disord. (2019) 246:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.043

41. Weeks DG, Michela JL, Peplau LA, Bragg ME. Relation between loneliness and depression: a structural equation analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1980) 39:1238. doi: 10.1037/h0077709

42. Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, Williams SL, Alley SJ, Thwaite TL, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4065. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114065

43. Brock RL, Laifer LM. Family science in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: solutions and new directions. Fam Process. (2020) 59:1007–17. doi: 10.1111/famp.12582

44. Alonzi S, La Torre A, Silverstein MW. The psychological impact of preexisting mental and physical health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S236–S8. doi: 10.1037/tra0000840

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, pandemic (COVID-19), anxiety, depression

Citation: Kantor BN and Kantor J (2020) Mental Health Outcomes and Associations During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study in the United States. Front. Psychiatry 11:569083. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569083

Received: 04 June 2020; Accepted: 02 November 2020;

Published: 09 December 2020.

Edited by:

Marinos Kyriakopoulos, King's College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Jorge Gaete, University of the Andes, ChileCopyright © 2020 Kantor and Kantor. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jonathan Kantor, am9ua2FudG9yQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; orcid.org/0000-0002-3256-3014

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.