- 1Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

- 2First Clinical School, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

- 3Department of Social Medicine and Health Management, Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, China

Background: Bullying tends to peak during adolescence, and it is an important risk factor of self-harm and suicide. However, research on the specific effect of different sub-types of bullying is limited.

Objective: The purpose of this study is to examine the associations between four common forms of bullying (verbal, physical, relational, and cyber) and self-harm, suicidal ideation (SI), and suicide attempts (SA).

Method: This was a cross-sectional study of a sample including 4,241 Chinese students (55.8% boys) aged 11 to 18 years. Bullying involvement, self-harm, SI, and SA were measured via The Juvenile Campus Violence Questionnaire (JCVQ). The association was examined through multinomial logistic regression analysis, adjusted for demographic characteristics and psychological distress.

Results: Bullying victimization and perpetration were reported by 18.0 and 10.7% of participants. The prevalence of self-harm, SI, and SA were 11.8, 11.8, and 7.1%, respectively. Relational bullying victimization and perpetration were significantly associated with SI only, SI plus self-harm, and SA. Physical bullying victimization and perpetration were risk factors of self-harm only and SA. Verbal victimization was significantly associated with SI only. Cyber perpetration was a risk factor of SA.

Conclusions: The findings highlight the different effects of sub-types of bullying on self-harm and suicidal risk. Anti-bullying intervention and suicide prevention efforts should be prior to adolescents who are involved in physical and relational bullying.

Introduction

Suicide is a substantial public health concern worldwide and is the third leading cause of death among youth aged 15–19 (1). In fact, more than 79% of global suicides occurred in low- and middle-income countries (1). In China, close to 2 million people attempt suicide and about 12.5% of them complete suicide every year (2). Furthermore, suicide has become the leading cause of death among Chinese young adults (2). Evidence significantly demonstrates that the presence of suicidal ideation (SI, thoughts and plans of ending one's life) and suicide attempts (SA, engagement in potentially self-injurious behavior that does not result in death) are the most important risk factors for suicide (3). According to a population-based study, the prevalence of SI and SA among Chinese adolescents was ~23 and 4%, respectively (4). In response to the high prevalence, researchers have identified risk factors for SI and SA, which range from psychopathology to interpersonal adversity, such as bullying (5).

Bullying is defined as intentional, repeated, and harmful aggressive behavior with an imbalance of power between the perpetrators and the victims. Bullying behavior can occur in a range of contexts including schools, communities, and through electronic means (6, 7). Bullying victimization and perpetration have been conceptualized into three common sub-types, including physical (e.g., hitting, kicking, chasing), verbal (e.g., teasing, name-calling), and social or relational (e.g., excluding or ostracizing from social situations, spreading rumors) (8, 9). In addition, the rapid development and widespread application of online communication have led to the emergence of cyber bullying, which is described as electronic aggression with harmful words or photographs through the computer or cell phone (10). The prevalence of bullying tends to peak during adolescence (11). Over one third of adolescents have experienced traditional bullying (e.g., verbal, physical, and relational) worldwide, whereas more than half of adolescents have reported cyber bullying (12, 13). Some previous research has also indicated that youth rarely experience cyber bullying independent of traditional bullying (14). Therefore, cyber bullying should be included when investigating different sub-types of bullying behavior in addition to verbal, physical, and relational bullying (15, 16).

Empirical evidence suggests that bullying is significantly associated with mental health problems (17), such as anxiety, depression, and psychosomatic symptoms (18, 19). In addition, adolescents who have been bullied are at a greater risk for self-harm and suicidal behavior than those who have not been a victim of bullying (20, 21). Critically, self-harm often co-occurs with SI and SA (22). However, few studies have explored the relationship of bullying perpetration, self-harm, and suicide risks, especially in eastern countries (23, 24). Klomek et al. found that bullying perpetration can predict subsequent SI and SA above and beyond other risk factors such as substance use and functional impairment (25). Therefore, besides victimization, perpetration must be incorporated into the analysis when examining associations between bullying, self-harm, and suicidal behaviors (26).

Despite the underestimation of bullying perpetration, the effect of specific sub-types of bullying behavior is poorly understood (27, 28). Although these sub-types are highly related to each other, they may be associated with adverse health outcomes in different patterns (29). For instance, Espelage and Holt found that youth who engaged in physical bullying had comparatively higher rates of self-harm, SI, and SA than those who were involved in verbal bullying (30). Arango et al. found that all sub-types of bullying victimization and perpetration, except for physical perpetration, were associated with an increased risk of SI. In addition, all forms of bullying, except for relational perpetration, were significantly associated with increased risk of SA (8). These studies claim that different sub-types of bullying behavior may have unique effects on self-harm and suicidal risk. However, these findings are controversial and based on a small adolescent sample (8). Therefore, it is necessary to examine the specific associations between different sub-types of bullying and self-harm, SI, and SA in a large and representative sample.

Furthermore, less is known about the adverse health-related outcomes of cyber bullying (31). Williams et al. found that cyber bullying could be a better predictor of depressive symptoms, SI, and SA as compared to verbal, physical, and relational bullying (11). Therefore, it is interesting to explore which one is the strongest risk factor of self-harm, SI, and SA in the full range of bullying victimization and perpetration, including verbal, physical, relational, and cyber (32).

Taken together, few studies have examined unique associations between bullying behavior and self-harm, SI, and SA in context of the four common sub-types of victimization and perpetration (verbal, physical, relational, and cyber). However, exploring the relationship between the severity of different sub-types of bullying and suicidal risk is particularly important for efficient prevention. More specifically, better understanding the effect of different sub-types of bullying could help medical providers to identify adolescents at the highest risk for suicidal behavior (33). Nevertheless, most of the previous studies on this issue were conducted in western countries and/or in a small sample (8, 11). Hence, it is necessary to extend the existing literature based on a large sample of adolescents in eastern and developing countries, such as China.

In order to address these gaps, the goal of the current study is to identify specific associations between sub-types of bullying and self-harm, SI, and SA in a large and random sample from a Chinese adolescent population. We aim to answer two main questions in the study: first, whether the four sub-types (verbal, physical, relational, and cyber) of bullying victimization and perpetration have distinct effects on self-harm, SI, and SA; and second, which sub-type of bullying has the strongest effect after adjusting for demographic characteristics and psychological distress.

Materials and Methods

Procedures

This study was a cross-sectional survey, conducted from March to October 2017. The participants were recruited via cluster sampling in Hubei Province, which is located in central China. First, we selected two cities (E'zhou and Xiaogan) randomly in the province. Second, with the help of local educational bureaus, we sampled three junior high schools and three senior high schools in each chosen city. Then, we selected two or three classes from 7th to 12th grade in every chosen school. Finally, all students from the chosen class were invited to the study as participants. All participants were required to complete the paper questionnaire independently, with the mean completion time between 20 to 30 min.

All students and their parents or guardians who participated in the study voluntarily signed informed written consent before investigation. The purpose of the study and the questionnaire sections were explained to them by investigators. The students were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of the information provided in the self-reported questionnaires. The study received the approval from the sample schools and the Medical Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. More information about the study has been described in https://osf.io/gckvu/?view_only=16e86f59733f45459c8de58fb1777046.

Participants

Questionnaires were sent out to 4,500 participants. After field investigation, we excluded 168 questionnaires due to some students having invalid responses (missing items of whole questionnaire were more than 15%). Then, based on the aims of this study, we excluded 91 questionnaires since participants did not provide information about the key variables of interest (e.g., bullying, self-harm, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempts). Finally, 4,241 (94.2%) questionnaires were included in the statistical analysis.

Bullying

The Juvenile Campus Violence Questionnaire (JCVQ) was developed by Chinese scholars to survey aggressive and violent behaviors on campus and had good validity and reliability (Cronbach's alpha was 0.91) in Chinese adolescent populations (34). The JCVQ provides a broader coverage of juvenile violent behaviors and assesses 36 items referring to victimization or perpetration covering 9 dimensions of interest: physical aggression, self-harm, suicide, sexual abuse, verbal aggression, relational aggression, cyber violence, tools violence (aggression with weapon), and peer pressure. All 36 items were assessed with the same question, asking how often the event occurred during the past year. Responses were scored on a 4-point, Likert-type scale, where 1 = “never,” 2 = “sometimes,” 3 = “often,” and 4 = “almost.” The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of the JCVQ in the study was 0.90. The Cronbach's alpha score for 9 dimensions of the JCVQ ranged from 0.83 to 0.94.

For this study, four sub-types of bullying behavior were measured via 16 items (8 items for victimization and 8 items for perpetration) from four dimensions (verbal aggression, physical aggression, relational aggression, cyber violence) using the JCVQ. Specifically, (1) verbal victimization: “I was called nasty name.” “I was made fun of.” (2) Physical victimization: “I was hit, kicked, pushed, or shoved.” “My belongings were taken or damaged.” (3) Relational victimization: “I was excluded from the group or completely ignored.” “Someone told lies or spread rumors about me and/or tried to make others dislike me.” (4) Cyber victimization: “I was called nasty name or made fun of online.” “Someone spread rumors about me online.” According to the well-accepted definition that bullying refers to some repetitive aggressive behaviors (35), participants were considered to be involved in a form of bullying victimization (coded 1) if the response of any specific item was 3 = “often” or 4 = “almost,” whereas they were coded 0 if the response was 1 = “never” or 2 = “sometimes.” Then, bullying perpetration was measured in the same pattern mentioned above.

The JCVQ does not require respondents to define themselves as bullies or victims, but rather asks about the frequency of each event related to bullying behavior. The instructions for the JCVQ are straightforward but do not provide a definition of bullying. This is because prior research has demonstrated that even when people do not label themselves as victims or bullies, they still suffer negative effects (36, 37).

In bullying involvement, “victim only” was defined as participants involved in any sub-type of bullying victimization but not engaging in perpetration. “Bully only” was classified as youth who perpetrated bullying behavior to others but were not bullied. “Bully-victim” was defined as a youth who experienced both bullying victimization and perpetration. Those who neither bullied others nor were bullied by others were classified as “non-involved” (38, 39).

Self-Harm, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicide Attempts

Self-harm, suicidal ideation (SI), and suicide attempts (SA) were measured through three items from JCVQ. (1) Self-harm: “I hurt myself intentionally by cutting or burning my skin.” (2) SI: “I thought about killing myself.” (3) SA: “I try to commit suicide.” Participants were considered to have self-harm, SI, or SA (coded 1) if the response was 2 = “sometimes,” 3 = “often,” or 4 = “almost,” while they were coded 0 if the response was 1 = “never” (40).

Psychological Distress

The 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K-10) was used to measure symptoms of psychological distress occurring over the last 4 weeks (41). The K-10 was most often treated as a unidimensional scale and has good validity in community and clinical settings among adolescent and adult populations (42). The Chinese version of K-10 has good validity and reliability (Cronbach's alpha was 0.80) among the Chinese population according to previous findings (43). Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = “none of the time,” 2 = “a little of the time,” 3 = “some of the time,” 4 = “most of the time,” and 5 = “all of the time.” Responses were summed to generate a total score ranging from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress (44). Multiple cut-offs were used to split populations into four groups representing low (10–15 score), moderate (16–21 score), high (22–29 score), and very high (30–50 score) levels of psychological distress (41). The Cronbach's alpha of the K-10 in this study was 0.89.

Demographic Variables

Demographic variables included gender, grade (from 7th to 12th), family composition (participant lives in a family with: 1= two biological parents, 2 = a single biological parent, 3 = others) (45), caregiver (1= parents, 2 = grandparents, 3 = other), caregiver's education (1 = primary school or less, 2 = junior high school, 3 = senior high school, 4 = college or more), and family income (average family income per month in RMB: 1 = ~ 999, 2 = 1000 ~ 2999, 3 = 3000 ~ 4999, 4 = 5000 ~ 7999, 5 = 8000 ~).

Statistical Analysis

First, demographic characteristics of participants and prevalence of bullying, self-harm, SI, and SA were summarized by descriptive statistics [n (%)]. Second, the chi-square test was used to compare the prevalence of self-harm, SI, and SA in different sub-types (verbal, physical, relational, and cyber) of bullying. Pearson's correlation was used among four sub-types of bullying, self-harm, SI, and SA.

Then, in order to examine the associations between sub-types of bullying and self-harm, SI, and SA, two models of multinomial logistic regression analyses were performed separately. In model 1, we included four sub-types of bullying victimization and perpetration (1= yes, 0 = no) as independent variables. In model 2, in addition to the four sub-types of bullying victimization and perpetration, we included gender, grade, family composition, caregiver, caregiver's education, family income, and psychological distress score as confounding variables. As some of the participants would have simultaneously experienced self-harm, SI, and SA, we classified participants into five categories: 0 = none (without self-harm, SI, and SA), 1= self-harm only, 2 = SI only, 3 = SI plus self-harm (simultaneous SI and self-harm but not SA), and 4 = SA (regardless of whether they experienced SI or self-harm) (4). The dependent variable of the multinomial logistic regression analysis was the five categories (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4).

The associations were reported via odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All data was analyzed by SPSS 23.0.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

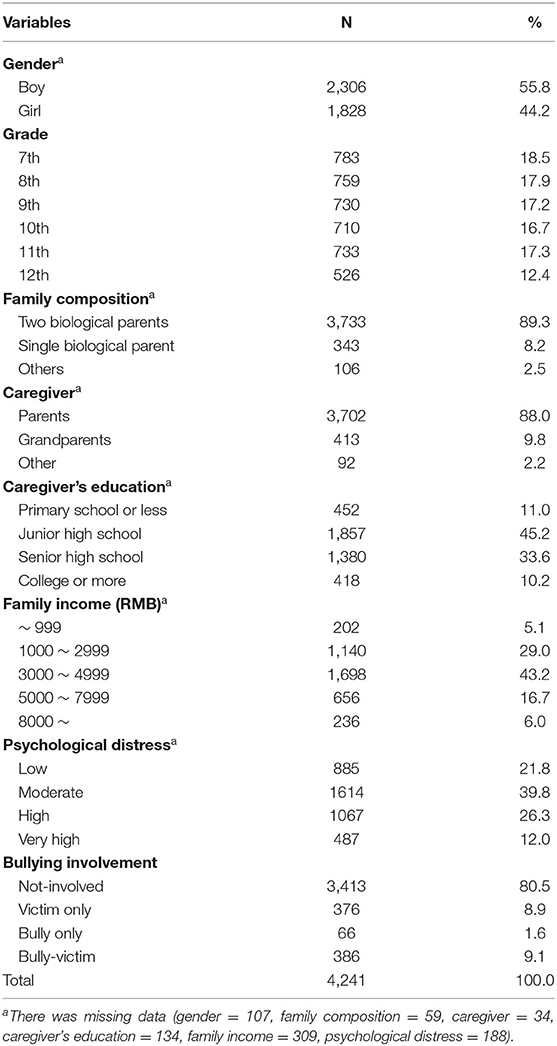

Among 4,241 participants, 2,306 were boys (55.8%), 1,828 were girls (44.2%), and 107 were missing. Their ages ranged from 11 to 18 years. The average age was 14.36 ± 1.80. There were slightly more junior high school students (grades 7 to 9) than senior high school students (grades 10 to 12) (53.6 vs. 46.4%). Most participants lived in a two biological parent family (89.3%), while 8.2% were from a single biological parent family and 2.5% from other type of family. The distribution of caregiver, caregiver's education, and family income is shown in Table 1.

Prevalence of Bullying, Self-Harm, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicide Attempts

In the study, 19.5% (828) of participants were involved in bullying behavior during the last year. With respect to bullying status, 8.9% (376) of participants were victim only, 1.6% (66) were bully only, and 9.1% (386) were bully-victim (Table 1). The mean and standard deviations (SD) for the total psychological distress score was 20.93 ± 6.98.

Prevalence of self-harm, suicidal ideation (SI), and suicide attempts (SA) were 11.8% (502), 11.8% (500), and 7.1% (300), respectively. Of the participants, 18.0% (762) reported at least one subtype of bullying victimization in the last year. The prevalence of the four sub-types of bullying victimization were 11.9% (verbal), 10.6% (physical), 4.0% (relational), and 4.8% (cyber). In bullying perpetration, 10.7% (457) of adolescents bullied others with any sub-type of bulling behavior. The prevalence of the four sub-types of bullying perpetration were 7.9% (verbal), 5.3% (physical), 4.2% (relational), and 3.6% (cyber). In the chi-square tests, adolescents involved in any form of bullying victimization or perpetration had higher rates of self-harm, SI, and SA than those who were not engaged in the sub-type of bullying (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts by sub-types of bullying [n (%)].

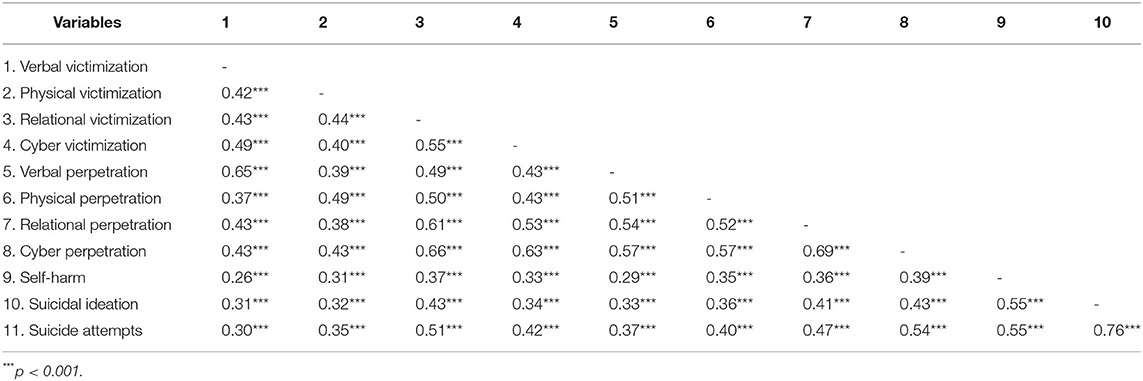

Associations Between Sub-types of Bullying and Self-Harm, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicide Attempts

Pearson's correlations among sub-types of bullying, self-harm, SI, and SA were displayed in Table 3. In Collinearity diagnosis of logistic regression analysis, Eigenvalue ranged from 0.226 to 4.847, Condition Index ranged from 1.000 to 4.631, and Variance Proportions ranged from 0.01 to 0.56. The results indicated that four sub-types of bullying victimization and perpetration were independently associated with self-harm, SI, and SA.

Table 3. Correlations among sub-types of bullying, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts.

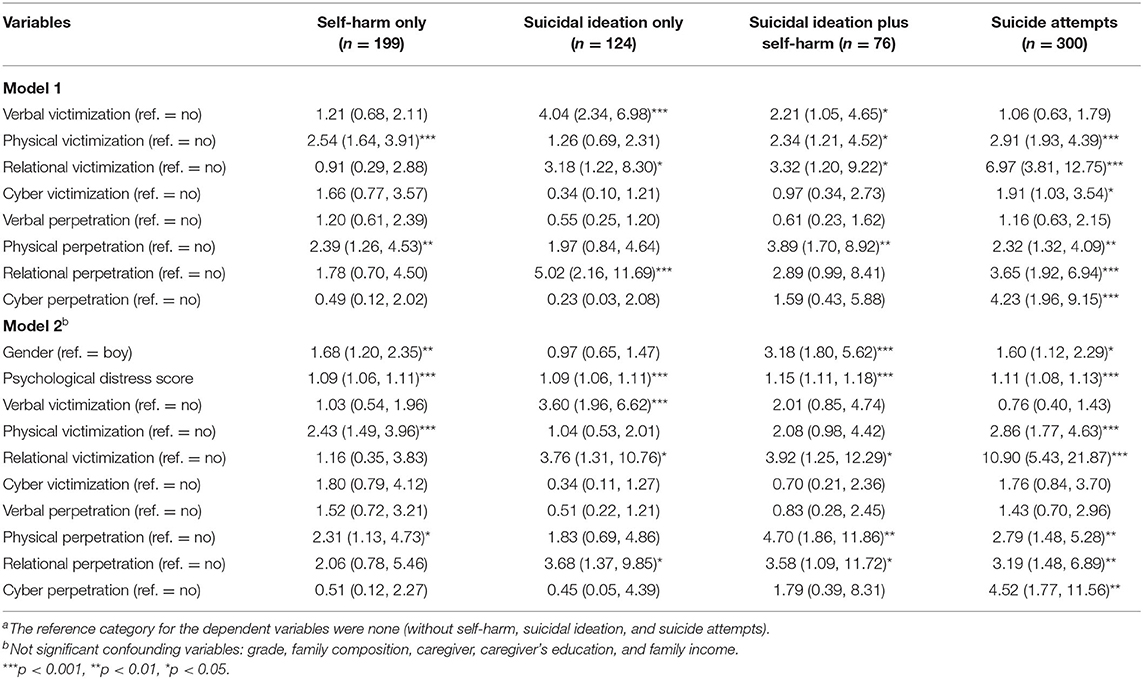

In model 1, without controlling for confounding variables, physical victimization and perpetration were significantly associated with self-harm only. Relational victimization and perpetration, as well as verbal victimization, were significantly associated with SI only. There were significant associations between SI plus self-harm and verbal, physical, and relational victimization as well as physical perpetration. All sub-types of bullying, except for verbal victimization and perpetration, were significantly associated with an increased risk of SA (Table 4).

Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression of self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts [OR (95% CI)]a.

In model 2, after controlling for confounding variables, results were similar to that of model 1 for self-harm only and SI only. SI plus self-harm was significantly associated with relational victimization and perpetration as well as physical perpetration. All sub-types of bullying, except for verbal victimization and perpetration as well as cyber victimization, were significantly associated with increased risk of SA (Table 4).

Additionally, the results showed that the psychological distress score was significantly associated with self-harm, SI, and SA. Compared with boys, girls had a greater risk of experiencing self-harm only, SI plus self-harm, and SA. Grade, family composition, caregiver, caregiver's education, and family income had no significant association with the dependent variable.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the effects of different sub-types (verbal, physical, relational, and cyber) of bullying victimization and perpetration on self-harm, suicidal ideation (SI), and suicide attempts (SA) through a large and random sample of adolescents in an Eastern country. First, we found that not all forms of bullying were significantly associated with self-harm, SI, and SA after controlling for some confounding variables, such as psychological distress. Most important, physical and relational bullying, in terms of both victimization and perpetration, might be the stronger risk factors for self-harm and suicide than verbal and cyber bullying. These findings contribute new information concerning the association between bullying and suicidal behavior among adolescents. Researchers could benefit from a better understanding of the specific effect of different sub-types of bullying on suicide.

As we expected, the effect of different sub-types of bullying victimization and perpetration on elevated risk of self-harm, SI, and SA were unique. First, physical bullying was positively associated with self-harm only, SI plus self-harm, and SA, while verbal victimization was associated with SI only. The finding is consistent with previous work, which indicated that physical bullying has a more serious impact on suicidal thoughts and behaviors than verbal bullying among youth (30). On the one hand, the different impact of these two forms of bullying may be rooted in that verbal bullying is more common than physical bullying among adolescents, which affects the risk to a lesser degree (46, 47). On the other hand, the involvement of physical bullying could put adolescents in situations where they are actually injured with physical pain or a threat of injury. Exposure to painful and provocative events could make adolescents more likely to engage in behavior leading to suicide (48).

Second, our results revealed that relational bullying was a strong risk factor for SI and SA, though the association between relational bullying and self-harm only was not significant. A previous study found that relational bullying (social exclusion and rumor spreading) had the strongest association with mental health problems, independent of verbal and physical bullying (49). Another study suggested that relational bullying may be especially detrimental to adolescent adjustment (50). This form of bullying generally causes a more adverse impact on adolescent self-esteem and social status than other forms of bullying (33). Our study extends these findings, highlighting that relational bullying has a stronger association with suicidal risk, independent of other forms of bullying behavior (51).

Relational bullying behavior, such as social exclusion from a group, is subtle and difficult to detect. Therefore, it is less likely to get appropriate attention from adults. This may contribute to the reason why the behavior persists for a longer time and makes self-defense more difficult, which further lead to stress and isolation (52). Adolescents may be particularly sensitive to social exclusion and rumor spreading as it deprives them of their social networks. During adolescence, acceptance and popularity within peer group are critical since youth individuate from their parents (53). Moreover, in this period, adolescents' social-cognitive skills develop rapidly. Therefore, relational bullying may have a more severe impact on adolescents' mental health due to the increased salience of peer relationships and sensitivity to peer rejection during this developmental period (46).

Most researchers treat verbal, physical, and relational bullying as one type called traditional bullying or school bullying (4, 16). It is hard to find specific characteristics of sub-types of bullying behavior and underlying distinct effects on adverse physical and/or mental health consequences. According to the results from the current study, severity of verbal, physical, and relational bullying victimization and perpetration for self-harm, SI, or SA are different. Therefore, it is more suitable to treat different forms of bullying behavior as independent variables when exploring the relationship between bullying and subsequent health problems.

Moreover, our results indicate the unique contribution of cyber bullying in suicide risk. Specifically, only cyber perpetration was significantly associated with SA. This finding was not in line with previous studies, which indicated that cyber bullying could have a more harmful effect on suicide than traditional bullying (21). The discordance may stem from the different classification of bullying behavior. Prior work generally did not distinguish verbal, physical, and relational bullying as a certain sub-type of bullying to compare with cyber bullying. It would weaken the effect of a specific form of bullying on mental health outcomes. Although cyber victimization was not a risk factor of self-harm and suicide risk, it could leave youth feeling extremely isolated and/or helpless, because cyber bullying is not restricted to school campuses and can happen at any time (54).

The prevalence of bullying in this study was lower than that reported in other studies (12, 55). First, the difference in prevalence may result from variations of cultural and economic backgrounds of different countries or regions (47). Second, it could stem from different measurements and cut-off values of bullying behavior in various studies (12). For instance, in the current study, we took a more stringent cut-off value and participants were classified as a victim or perpetrator if any bullying behavior “often” or “almost” happened, while adolescents were identified to have experienced bullying when the frequency was “sometimes” in a recent study (4). In addition, the prevalence of cyber bullying was also lower than reported in other studies, which were mainly conducted in Western developed countries (56, 57). One possible explanation is that most of the junior and senior high students in China attend boarding school. Students stay at school for five or six days a week and they are not allowed to use mobile phones or other online devices at school.

Over and above different sub-types of bullying, we found that psychological distress is significantly associated with self-harm, SI, and SA. Existing literature has demonstrated that there is a positive correlation between bullying experiences and psychological distress (58). Previous researchers have indicated that severe psychological distress is a major risk factor for suicidal behavior (59). Hence, we included psychological distress as a confounder when we examined the relationship between bullying and suicide. The finding may be beneficial for better understanding of predictive factors for suicide risk.

Limitations

There are several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design and self-reported data limit our study to draw causal associations between bullying and self-harm, SI, and SA. Future studies could benefit from the use of a longitudinal, multi-informant, multi-method design. Second, the current study dichotomized each of the sub-types of bullying as independent variables and did not consider the co-occurrence of different forms of bullying. It would be beneficial to explore the specific effect on self-harm and suicidal risk, but the cumulative effect of bullying cannot be examined. Further, we did not consider other possible confounding variables, such as school environment, sexual orientation, or obesity, which may moderate the association between bullying and suicidality (60, 61). Future research should include more potential cofounders. Finally, although the sample size was large, the study was conducted within one province of China. The extent to which this sample represents is unclear. Future research can recruit more participants in several representative provinces in China via a multi-center sampling design.

Implications

The findings provide valuable implications for prevention strategies to decrease rates of bullying and suicide. Results from the current study indicated that relational bullying could be a strong risk factor for suicide in all sub-types of bullying. This finding supports the role of thwarted belongingness in predicting suicide risk, which is an essential component of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicidal Behavior (62). Adolescents bullied in a relational way may suffer more unbearable mental pain and lack of belonging, which could increase the risk of suicidality (63). Therefore, it is important to reinforce interpersonal connectedness in youth who are victims of relational bullying. Interpersonal connectedness could be improved via participating in group projects, engaging in team activities, or being involved in school events (8). In addition, our results demonstrate that not all sub-types of bullying are significantly associated with self-harm or suicide. This finding supports the importance of differentiating sub-types of bullying behavior, which can help suicide prevention strategies on specific needs for adolescents involving in bullying. On the other hand, researchers are supposed to design more work to delineate how and why different sub-types of bullying victimization and perpetration have distinct associations with physical and psychological health problems among adolescents.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the specific effects of different sub-types of bullying victimization and perpetration on self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Different strategies, based on unique characteristics of different forms of bullying behavior, can be more effective than a one-size-fits-all approach in the development of suicide prevention programs. Anti-bullying intervention and suicide prevention efforts should be aimed to adolescents who are involved in physical and relational bullying, as they face a greater risk of self-harm and suicidality.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

CP and WH as the first authors, developed the initial manuscript and contributed equally to this paper work. SY, JX, and CK were responsible for the data collection and the data analysis. MW, FR, and YH contributed substantially to the revision and refinement of the final manuscript. YY guided the overall design of the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number is 81573172).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank students who took part in the survey, parents who supported the work, teachers who assisted with the field investigation, and all investigators.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Suicide. 2/2/2019. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (Accessed 4/13 2020).

2. National Health Commission of People's Republic of China. World Suicide Prevention Day. Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/zjyfzsr/hexx/list.shtml (Accessed 4/13 2020).

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Suicide Prevention. Available online at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/suicide#tab=tab_2 (Accessed 4/13 2020).

4. Peng Z, Klomek AB, Li L, Su X, Sillanmaki L, Chudal R, et al. Associations between Chinese adolescents subjected to traditional and cyber bullying and suicidal ideation, self-harm and suicide attempts. BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2319-9

5. Klomek AB, Sourander A, Gould M. The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: a review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. Canad J Psychiatry Revue Canad Psych. (2010) 55:282–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.196.5.422

6. Vaillancourt T, Mcdougall P, Hymel S, Krygsman A, Miller J, Stiver K, et al. Bullying: are researchers and children/youth talking about the same thing? Int J Behav Dev. (2008) 32:486–95. doi: 10.1177/0165025408095553

7. Gladden R, Vivolo-Kantor A, Hamburger M, Lumpkin C. Bullying Surveillance Among Youths: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014).

8. Arango A, Opperman KJ, Gipson PY, King CA. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among youth who report bully victimization, bully perpetration and/or low social connectedness. J Adolesc. (2016) 51:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.003

9. Bradshaw CP, Waasdorp TE, Johnson SL. Overlapping verbal, relational, physical, and electronic forms of bullying in adolescence: influence of school context. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2015) 44:494–508. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.893516

10. Kiriakidis SP, Kavoura A. Cyberbullying a review of the literature on harassment through the internet and other electronic means. Fam Community Health. (2010) 33:82–93. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181d593e4

11. Williams SG, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Wornell C, Finnegan H. Adolescents transitioning to high school: sex differences in bullying victimization associated with depressive symptoms, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts. J Sch Nurs. (2017) 33:467–79. doi: 10.1177/1059840516686840

12. Modecki KL, Minchin J, Harbaugh AG. Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. (2014) 55:602–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007

13. Craig W, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H, Dostaler S, Hetland J. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Int J Public Health. (2009) 54:216–24. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5413-9

14. Salmivalli C, Sainio M, Hodges EVE. Electronic victimization: correlates, antecedents, and consequences among elementary and middle school students. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2013) 42:442–53. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.759228

15. Waasdorp TE, Bradshaw CP. The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 56:483–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.002

16. Schneider SK, O'donnell L, Stueve A, Coulter RW. Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: a regional census of high school students. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:171–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2011.300308

17. Wolke D, Lereya ST. Long-term effects of bullying. Arch Dis Childhood. (2015) 100:879–85. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306667

18. Kaltiala-Heino R, Fröjd S, Marttunen M. Involvement in bullying and depression in a 2-year follow-up in middle adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2009) 19:45. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0039-2

19. Sourander A, Brunstein Klomek A, Ikonen M, Lindroos J, Luntamo T, Koskelainen M, et al. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: a population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2010) 67:720–8. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.79

20. Fisher HL, Moffitt TE, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Arseneault L, Caspi A. Bullying victimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: longitudinal cohort study. Bmj. (2012) 344:e2683. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2683

21. Van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J. Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. (2014) 168:435–42. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4143

22. Stewart JG, Esposito EC, Glenn CR, Gilman SE, Pridgen B, Gold J, et al. Adolescent self-injurers: Comparing non-ideators, suicide ideators, and suicide attempters. J Psychiatric Res. (2017) 84:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.031

23. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suic Res. (2010) 14:206–21. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2010.494133

24. Kim YS, Leventhal B. Bullying and suicide. A review. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2008) 20:133–54. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2008.20.2.133

25. Klomek AB, Kleinman M, Altschuler E, Marrocco F, Amakawa L, Gould MS. Suicidal adolescents' experiences with bullying perpetration and victimization during high school as risk factors for later depression and suicidality. J Adolesc Health. (2013) 53(1, Supplement):S37–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.008

26. Vergara GA, Stewart JG, Cosby EA, Lincoln SH, Auerbach RP. Non-Suicidal self-injury and suicide in depressed adolescents: impact of peer victimization and bullying. J Affect Disord. (2019) 245:744–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.084

27. Holt MK, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Polanin JR, Holland KM, Degue S, Matjasko JL, et al. Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2015) 135:e496–509. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1864

28. Strohacker E, Wright LE, Watts SJ. Gender, bullying victimization, depressive symptoms, and suicidality. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. (2019) 2019:1–20. doi: 10.1177/0306624x19895964

29. Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Luk JW, Nansel TR. Co-occurrence of victimization from five subtypes of bullying: physical, verbal, social exclusion, spreading rumors, and cyber. J Pediat Psychol. (2010) 35:1103–12. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq048

30. Espelage DL, Holt MK. Suicidal ideation and school bullying experiences after controlling for depression and delinquency. J Adolesc Health. (2013) 53:S27–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.017

31. Pham T, Adesman A. Teen victimization: prevalence and consequences of traditional and cyberbullying. Curr Opin Pediatr. (2015) 27:748–56. doi: 10.1097/mop.0000000000000290

32. Campbell M, Spears B, Slee P, Butler D, Kift S. Victims' perceptions of traditional and cyberbullying, and the psychosocial correlates of their victimisation. Emot Behav Difficult. (2012) 17:389–401. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2012.704316

33. Kodish T, Herres J, Shearer A, Atte T, Fein J, Diamond G. Bullying, depression, and suicide risk in a pediatric primary care sample. Crisis. (2016) 37:241–6. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000378

34. Zhi KY, Chen YJ, Xia W, You YL, Zhang LL. Development and evaluation of juvenile campus violence questionnaire. China J Public Health. (2013) 29:179–82. doi: 10.11847/zgggws2013-29-02-08

35. Smith PK. Bullying: definition, types, causes, consequences and intervention. Soc Pers Psychol Comp. (2016) 10:519–32. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12266

36. Vie TL, Glaso L, Einarsen S. Health outcomes and self-labeling as a victim of workplace bullying. J Psychosom Res. (2011) 70:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.06.007

37. Radoman M, Akinbo FD, Rospenda KM, Gorka SM. The impact of startle reactivity to unpredictable threat on the relation between bullying victimization and internalizing psychopathology. J Psychiatr Res. (2019) 119:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.09.004

38. Hepburn L, Azrael D, Molnar B, Miller M. Bullying and suicidal behaviors among urban high school youth. J Adolesc Health. (2012) 51:93–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.014

39. Liu X, Peng C, Yu Y, Yang M, Qing Z, Qiu X, et al. Association between sub-types of sibling bullying and mental health distress among Chinese children and adolescents. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:368. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00368

40. Sigurdson JF, Undheim AM, Wallander JL, Lydersen S, Sund AM. The longitudinal association of being bullied and gender with suicide ideations, self-harm, and suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood: a cohort study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2018) 48:169–82. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12358

41. Slade T, Grove R, Burgess P. Kessler Psychological Distress Scale: Normative Data From The 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2011) 45:308–16. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.543653

42. Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Zamorski MA, Colman I. The psychometric properties of the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) in Canadian military personnel. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0196562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196562

43. Zhou CC, Chu J, Wang T, Peng QQ, He JJ, Zhen WG, et al. Reliability and validity of 10-item Kessler Scale (K10) Chinese version in evaluation of Mental Health Status of Chinese Population. Chinese J Clin Psychol. (2008) 16:627–9. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2008.06.026

44. Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Willmore J. Relationships between bullying victimization psychological distress and breakfast skipping among boys and girls. Appetite. (2015) 89:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.01.020

45. Attar-Schwartz S, Tan JP, Buchanan A, Flouri E, Griggs J. Grandparenting and adolescent adjustment in two-parent biological, lone-parent, and step-families. J Fam Psychol. (2009) 23:67–75. doi: 10.1037/a0014383

46. Thomas HJ, Chan GCK, Scott JG, Connor JP, Kelly AB, Williams J. Association of different forms of bullying victimisation with adolescents' psychological distress and reduced emotional wellbeing. Austr N Zeal J Psychiatry. (2016) 50:371–9. doi: 10.1177/0004867415600076

47. Wang CW, Musumari PM, Techasrivichien T, Suguimoto SP, Tateyama Y, Chan CC, et al. Overlap of traditional bullying and cyberbullying and correlates of bullying among Taiwanese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1756. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-8116-z

48. Bender TW, Gordon KH, Bresin K, Joiner TE. Impulsivity and suicidality: the mediating role of painful and provocative experiences. J Affect Disord. (2011) 129:301–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.023

49. Baldry AC. The impact of direct and indirect bullying on the mental and physical health of Italian youngsters. Aggress Behav. (2004) 30:343–55. doi: 10.1002/ab.20043

50. Helms SW, Gallagher M, Calhoun CD, Choukas-Bradley S, Dawson GC, Prinstein MJ. Intrinsic religiosity buffers the longitudinal effects of peer victimization on adolescent depressive symptoms. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2015) 44:471–9. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.865195

51. Crick NR, Casas JF, Nelson DA. Toward a more comprehensive understanding of peer maltreatment: studies of relational victimization. Curr Direct Psychol Sci. (2002) 11:98–101. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00177

52. Vaillancourt T, editor. Indirect Aggression Among Humans: Social Construct or Evolutionary Adaptation? New York, NY: The Guilford Press (2005).

53. Marini ZA, Dane AV, Bosacki SL, Cura Y. Direct and indirect bully-victims: differential psychosocial risk factors associated with adolescents involved in bullying and victimization. Aggress Behav. (2006) 32:551–69. doi: 10.1002/ab.20155

54. Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2008) 49:376–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

55. Caliskan Z, Evgin D, Bayat M, Caner N, Kaplan B, Ozturk A, et al. Peer bullying in the preadolescent stage: frequency and types of bullying and the affecting factors. J Pediat Res. (2019) 6:169–79. doi: 10.4274/jpr.galenos.2018.26576

56. Callaghan M, Kelly C, Molcho M. Exploring traditional and cyberbullying among Irish adolescents. Int J Public Health. (2015) 60:199–206. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0638-7

57. Rice E, Petering R, Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, Goldbach J, Plant A, et al. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among middle-school students. Am J Public Health. (2015) 105:e66–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.302393

58. Iwanaga M, Imamura K, Shimazu A, Kawakami N. The impact of being bullied at school on psychological distress and work engagement in a community sample of adult workers in Japan. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0197168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197168

59. Tanji F, Tomata Y, Zhang S, Otsuka T, Tsuji I. Psychological distress and completed suicide in Japan: a comparison of the impact of moderate and severe psychological distress. Prev Med. (2018) 116:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.09.007

60. Kevin S, Wagner KA, Velloza J. Estimating the magnitude of the relation between bullying, E-bullying, and suicidal behaviors among United States Youth, 2015. Crisis. (2018) 40:157–65. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000544

61. Kim HHS, Chun J. Bullying victimization, school environment, and suicide ideation and plan: focusing on youth in low- and middle-income countries. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 66:115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.006

Keywords: adolescents, suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, self-harm, bullying

Citation: Peng C, Hu W, Yuan S, Xiang J, Kang C, Wang M, Rong F, Huang Y and Yu Y (2020) Self-Harm, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicide Attempts in Chinese Adolescents Involved in Different Sub-types of Bullying: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 11:565364. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565364

Received: 25 May 2020; Accepted: 23 October 2020;

Published: 03 December 2020.

Edited by:

Megan Stubbs-Richardson, Mississippi State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kristen Stives, Auburn University at Montgomery, United StatesJessica Utley, Mississippi State University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Peng, Hu, Yuan, Xiang, Kang, Wang, Rong, Huang and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yizhen Yu, eXV5aXpoZW42NTBAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Chang Peng

Chang Peng Wenzhu Hu2†

Wenzhu Hu2† Yizhen Yu

Yizhen Yu