94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 26 June 2020

Sec. Psychological Therapies

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00483

Meaghan Louise O'Donnell1,2*†

Meaghan Louise O'Donnell1,2*† Winnie Lau1,2†

Winnie Lau1,2† Julia Fredrickson1,2

Julia Fredrickson1,2 Kari Gibson1,2

Kari Gibson1,2 Richard Allan Bryant3

Richard Allan Bryant3 Jonathan Bisson4†

Jonathan Bisson4† Susie Burke5

Susie Burke5 Walter Busuttil6

Walter Busuttil6 Andrew Coghlan7

Andrew Coghlan7 Mark Creamer2†

Mark Creamer2† Debbie Gray8†

Debbie Gray8† Neil Greenberg9†

Neil Greenberg9† Brett McDermott10†

Brett McDermott10† Alexander C. McFarlane11†

Alexander C. McFarlane11† Candice M. Monson12

Candice M. Monson12 Andrea Phelps1,2†

Andrea Phelps1,2† Josef I. Ruzek13,14†

Josef I. Ruzek13,14† Paula P. Schnurr15,16†

Paula P. Schnurr15,16† Janette Ugsang17

Janette Ugsang17 Patricia Watson13

Patricia Watson13 Shona Whitton7

Shona Whitton7 Richard Williams18

Richard Williams18 Sean Cowlishaw1,2,19†

Sean Cowlishaw1,2,19† David Forbes1,2†

David Forbes1,2†Background: In the aftermath of disaster, a large proportion of people will develop psychosocial difficulties that impair recovery, but for which presentations do not meet threshold criteria for disorder. Although these adjustment problems can cause high distress and impairment, and often have a trajectory towards mental health disorder, few evidence-based interventions are available to facilitate recovery.

Objective: This paper describes the development and pilot testing of an internationally developed, brief, and scalable psychosocial intervention that targets distress and poor adjustment following disaster and trauma.

Method: The Skills fOr Life Adjustment and Resilience (SOLAR) program was developed by an international collaboration of trauma and disaster mental health experts through an iterative expert consensus process. The resulting five session, skills-based intervention, deliverable by community-based or frontline health or disaster workers with little or no formal mental health training (known as coaches), was piloted with 15 Australian bushfire survivors using a pre-post with follow up, mixed-methods design study.

Results: Findings from this pilot demonstrated that the SOLAR program was safe and feasible for non-mental health frontline workers (coaches) to deliver locally after two days of training. Participants' attendance rates and feedback about the program indicated that the program was acceptable. Pre-post quantitative analysis demonstrated reductions in psychological distress, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and impairment.

Conclusions: This study provides preliminary evidence that the delivery of the SOLAR program after disaster by trained, frontline workers with little or no mental health experience is feasible, acceptable, safe, and beneficial in reducing psychological symptoms and impairment among disaster survivors. Randomized controlled trials of the SOLAR program are required to advance evidence of its efficacy.

It is well established that disasters of both natural (e.g., floods, bushfires, earthquakes) and human (e.g., mass violence, terrorism) origin can adversely impact mental health among those directly or indirectly exposed (1). A range of psychiatric disorders can develop in the aftermath of disaster exposure, including alcohol use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive–compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and major depressive disorder (2). Alongside losses, hardships, and other psychosocial stressors endured, these conditions not only cause great personal suffering and distress, but also interfere with family, social, and occupational functioning (3). The costs of the mental health consequences of disaster to the community in both human and financial terms is therefore enormous, and is currently recognized by global agencies as one of the most urgent public health issues (4).

In the short to longer-term aftermath of disaster, there is consensus for supporting a strategic, stepped model of care comprising universal, indicated, and standard treatment components (5). Approaches informed by Psychological First Aid (PFA) are often recommended as early universal intervention strategies, and are designed to foster cohesive, informational, practical, and mutual support (6, 7); although it is recognized that little research has confirmed that PFA approaches actually achieve these goals (8, 9). At the other end of the spectrum, substantial research exists to guide evidence-based psychological and pharmacological interventions for disaster survivors who present with diagnosable psychiatric conditions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (10). However, significant knowledge and practice gaps exist as to how best to assist the substantial number of people who develop disabling and distressing adjustment problems, or sub-clinical psychiatric conditions after disaster, that do not reach clinical thresholds for psychiatric diagnosis. Targeting interventions to this population through indicated interventions is essential for three key reasons: (i) there is evidence that most mental health difficulties following disaster are of a mild-to-moderate (i.e., subclinical) severity (11), (ii) psychological dysfunction at this level can cause significant distress, functional impairment, and economic loss (12), and (iii) these adjustment problems pose a risk for escalation into serious psychiatric disorders if not effectively addressed (13).

Scalability is an important issue when devising post-disaster psychosocial interventions. Such interventions need to be deliverable to potentially large numbers of people across diverse settings, and there is typically insufficient capacity to achieve this using existing mental health resources. One way to improve scalability is to design brief interventions, which are preferable for implementation purposes, as brevity minimizes the costs of delivery and reduces the burden on participants (14). “Task–shifting” is a feature of many recent, scalable, psychosocial initiatives, which moves delivery of interventions from mental health specialists to less qualified or trained personnel. Recent meta-analyses indicate that the use of non-specialists can lead to significant improvements in mental health (15).

There is growing evidence of the efficacy of brief, low-intensity interventions and their capacity to meet existing gaps in health care for persons with subclinical disorders. The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) stepped model of care, for example, introduced in the United Kingdom in 2008, incorporates low-intensity interventions delivered by psychological wellbeing practitioners (PWPs) for persons with mild-to-moderate depression and anxiety. PWPs, who do not typically belong to a mental health profession such as clinical psychology, social work, or mental health nursing, are trained to deliver the core IAPT low-intensity interventions and to act in the role of coaches. This approach has greatly expanded the proportion of UK residents benefitting from NICE recommended psychological interventions, and has substantially reduced waiting times for services (16, 17). Taking a similar approach to low and middle-income countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the brief scalable intervention, Problem Management Plus (PM+) (18, 19). PM+ is a five-session intervention that targets common mental health disorders such as depression or anxiety. PM+ has been subjected to randomized controlled trials in Pakistan (20) and Kenya (21), and in both cases has been shown to significantly improve mental health outcomes.

Despite these promising outcomes, there remains uncertainty regarding the capacity for scalable, low-intensity interventions to meet the needs of trauma survivors specifically. Few attempts have been made to develop interventions targeted specifically to disaster and/or trauma survivors, with one exception being the Skills for Psychological Recovery (SPR) program (22), a flexibly-delivered six-module intervention program delivered by generalist health providers or paraprofessionals. However, SPR does not include any emotional processing component, which has been found to be a frontline strategy for addressing posttraumatic emotional reactions (23). Notably, emotional processing is also not featured in the IAPT low-intensity interventions or PM+. Further, SPR has been critiqued as too complex for non-mental health professionals to deliver in practice (23). SPR is also limited by the absence of any published trials examining its efficacy since its development over a decade ago for disaster survivors following Hurricane Katrina in the USA.

Recognizing the gap in scalable, simple interventions that cater for the psychosocial needs of disaster and trauma survivors experiencing adjustment and subclinical mental health problems, an international group of experts were assembled to develop a new intervention: the Skills fOr Life Adjustment and Resilience (SOLAR) program. This paper describes the development, structure, and psychosocial treatment components of SOLAR, along with the findings of a pilot study assessing the feasibility of training non-mental health professionals and paraprofessionals to deliver SOLAR, and the safety and acceptability of the program among bushfire survivors in Australia.

The process for developing SOLAR was informed by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines for developing a complex intervention (24). It entailed an iterative expert consensus process involving: (i) the formation of an international expert group; (ii) a scoping process to identify relevant literature concerning mechanisms of trauma recovery and evidence-based interventions; (iii) a subsequent, iterative ranking process to identify and weight treatment components suitable for inclusion in the SOLAR program; (iv) a roundtable meeting of experts to enable final consensus on program components.

A SOLAR Development Group was established comprising 21 international experts in trauma or disaster mental health, and/or disaster response, from the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, and Asia. Experts were selected based on their profile expertise in disaster and mental health, evidenced by publication records, demonstrated impacts in their fields, and/or senior level experience and expertise in emergency or mental health disaster response. The SOLAR Development Group also included expert representation from frontline disaster response agencies, including the Australian Red Cross and the Asia Disaster Preparedness Center, to ensure the relevance and feasibility of the intervention.

A subgroup of the SOLAR Development Group (the Scientific Working Party) reviewed and identified empirical literature to determine mechanisms central to trauma recovery and components of evidence-based therapeutic approaches aligned with each recovery mechanism. In doing so, consideration was given to therapeutic approaches that focused on skills-development. The following mechanisms were identified and formed the basis for consensus building among the SOLAR development group: (1) managing arousal and distress/affect regulation [e.g., (25–30)]; (2) emotional processing and managing avoidance [e.g., (29, 31–38)]; (3) social support [e.g., (3, 39–45)]; (4) problem solving [e.g., (46, 47)]; (5) cognitive restructuring/control [e.g., (36, 48–52)]; (6) psychoeducation [e.g., (53–56)]; (7) activity scheduling and behavioural activation [e.g., (7, 46, 48, 57, 58)]; (8) healthy living and self-care [e.g., (7, 59)]; and (9) mindfulness [e.g., (26, 28)].

A summary of findings from the literature scoping process was circulated to the SOLAR Development Group, who provided comment and ranked components of the identified skill-based therapeutic approaches according to their suitability for SOLAR. Experts were also able to suggest additional therapeutic approaches for the Group's consideration. When ranking, the Development Group sought a balance between (i) efficacy and scalability, recognizing that this intervention needed to be effective while also being deliverable in a short time-frame by generalist and lay providers, and ii) specificity and generalizability, with the aim being to devise a program with universal application across disaster and potentially other large-scale traumatic events. The ranking process was repeated twice. After each ranking, the Scientific Working Party revised the intervention proposal and provided commentary on the level of consensus and rationale for the inclusion or exclusion of each component, according to expert feedback.

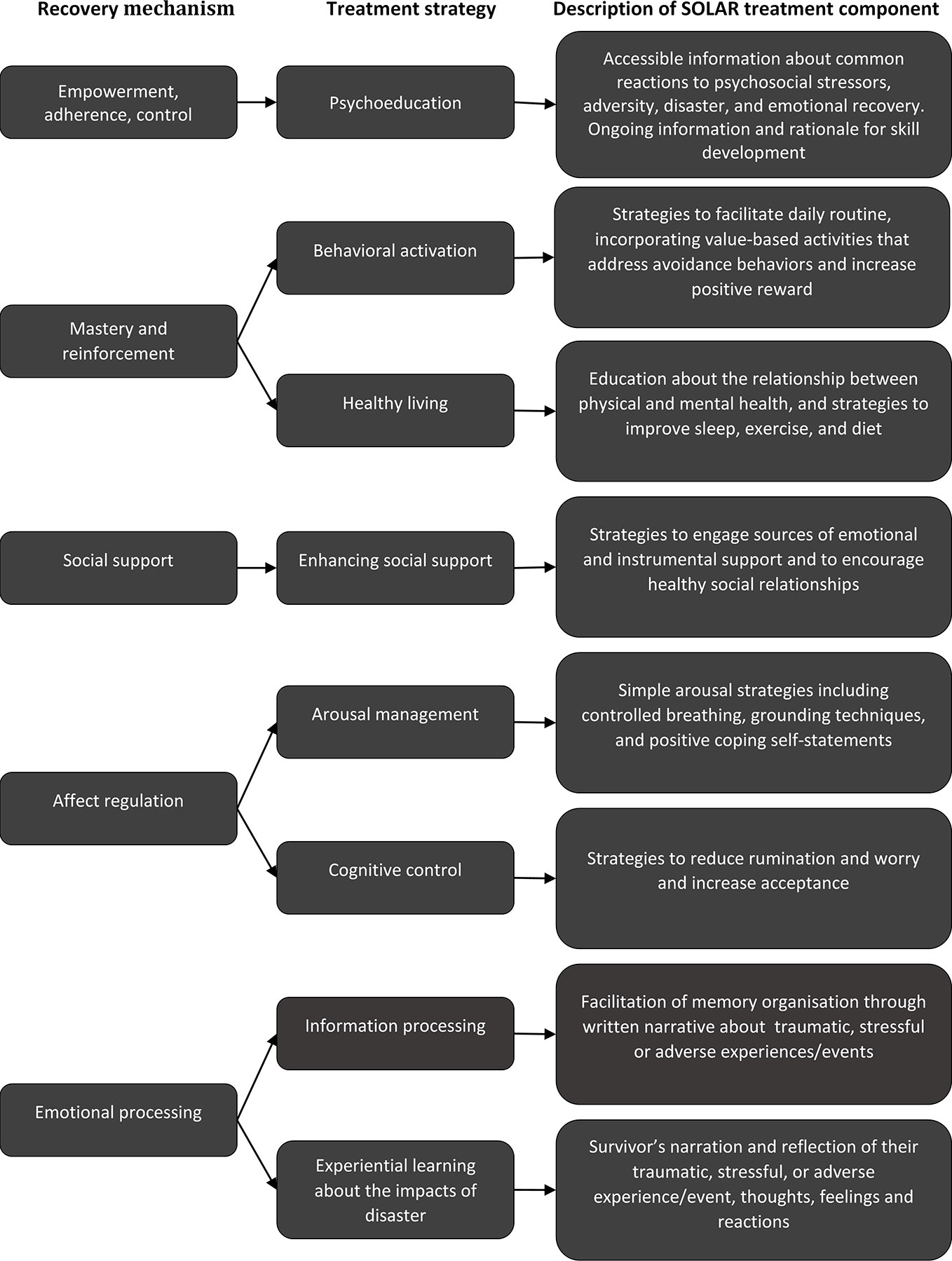

The consensus process culminated in a roundtable meeting held in Sydney, Australia in 2015, during which the SOLAR Development Group achieved consensus on the therapeutic components to be included in SOLAR, a preferred delivery format, and an approach for its evaluation. The decision-making process occurred with reference to the findings of the literature scoping and ranking process described above. The components included in the final program, together with the recovery mechanism they target, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The SOLAR program: Mechanisms of post-trauma and mental health recovery, relevant treatment strategies, and summary description of SOLAR treatment components.

Following the roundtable meeting the SOLAR content was developed and circulated to all those in the SOLAR Development Group for their input.

A workshop was conducted with end-users to present the beta version of SOLAR for input and discussion. The key focus of this consultation forum was to get feedback as to whether the information was in a format that could be easily understood and delivered by non-mental health experts. The resulting intervention program, SOLAR, constitutes a 5-session psychosocial intervention that targets subclinical psychiatric symptoms and adjustment difficulties in the medium-to-long term following disaster or trauma. It represents an intervention that lies between universal interventions and specialized interventions for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses, to enable a strategic, scalable, stepped model of post-trauma mental healthcare. The program comprises six modules, outlined in Table 1.

The SOLAR program is designed for delivery by volunteers, professionals, or paraprofessionals working in health or disaster response in communities affected by disaster. These providers, termed ‘coaches’ to program participation or practice, complete a 2-day training program before commencing the program with identified disaster/trauma survivors. Coaches are not expected to have specialist expertise in mental health, which increases the program's potential reach and helps to prevent overwhelming an already burdened mental healthcare system in the aftermath of disaster.

The role of coaches is to teach recovery skills, maintain motivation, encourage practice, reinforce effort, and problem-solve barriers to program participation or practice with participants. Following training, coaches are provided with a manual, and encouraged to work sequentially through the manualized program with a participant. Supervision is offered weekly, recognizing the critical role of on-going supervision for developing the skill base of non-mental health specialists. Supervision also assists with the identification of participants requiring more intensive or specialized treatment, consistent with a stepped-care approach (21). The supervision schedule may be varied once the coach completes the program with at least two participants and is regarded as competent by the supervisor.

Each SOLAR session runs for 50 min, with the exception of the first, 80-minute session. Sessions are delivered to participants face-to-face on a weekly basis, and can be provided at any easily accessible location in the community. Skills that the SOLAR Development Group prioritized for early gain are frontloaded, to avoid participants missing this information in the event of subsequent non-attendance or attrition, which is common in transient disaster populations. Maintenance of skill development beyond each session is promoted through practice tasks, which the participant completes between sessions. Each session also includes revision of the skills taught previously, and the final session constitutes a review of learning overall and the development of a plan for continued recovery into the future. Participants are given a workbook summarizing the content delivered in each session, which provides a clear rationale for undertaking practice tasks, and includes worksheets to help them complete tasks and monitor progress.

To assess the safety, feasibility, and acceptability of SOLAR, a single group study was conducted. Assessments were conducted at pre-intervention, post-intervention, and at 3-month follow-up. All eligibility screening and assessments were conducted by a trained research assistant via telephone. The study was conducted in 2016 with survivors of the January 2015 Sampson Flat bushfires and the November 2015 Pinery bushfires in South Australia. The trial took place in partnership with Country South Australia Primary Health Network (CSAPHN), the Northern Health Network (NHN), and the Australian Red Cross. Ethics approval was provided by the Health Sciences Human Ethics Sub-Committee of the University Of Melbourne. All participants underwent an informed consenting procedure and signed an informed consent form prior to participating.

Seven frontline workers were nominated by local partnering organizations and trained as coaches. They consisted of a community nurse, an intern social worker, two case workers, and three Australian Red Cross volunteers. Coaches completed a 2-day training workshop delivered by registered psychologists with trauma expertise. Coaches were provided with the SOLAR coach manual and participant workbook, as well as access to a “web-hub” developed to facilitate communication between coaches and supervisors, and to enable access to shared resources. Coaches' knowledge and understanding of the material, and their confidence in delivering SOLAR, was measured before and after the training workshops using a purposively designed, 14-item test. Readiness to act as a SOLAR coach was defined as a minimum of 80% correct in the knowledge items, and a minimum of 70% in confidence. Coaches attended weekly group supervision via teleconferencing for a minimum of two participants and until deemed competent in delivering SOLAR.

Fifteen participants were recruited over a six-month period via referral from local partnering organizations, or via self-referral in response to trial promotion materials. Trial promotional material was disseminated through local Red Cross bushfire-related activities, and through local general practitioner clinics. Figure 2 provides details of participant recruitment, screening, assessment, and program participation. Eligibility criteria were: (i) ≥18 years of age, (ii) directly experienced or impacted by the 2015 Sampson Flat or Pinery bushfires, according to self-report, (iii) subclinical anxiety, posttraumatic stress, or depression symptoms, as determined by cut-off scores on assessment measures, (iv) distress and impairment in social, occupational, or daily functioning, (v) no previous or current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, as determined by structured clinical interview, and (vi) availability for the program and not participating in other mental health treatments. Participants who were excluded because of severe distress or psychiatric symptoms were referred to an appropriate mental health service. Eligible participants were allocated to a coach based on location and availability. Sample demographic information is presented in Table 2.

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (60) was used as a screening measure of global psychological distress to determine inclusion into the pilot. The K10 comprises 10 items that rate symptoms along the anxiety–depression spectrum, with a five point Likert response option for each item, where 1 = symptom experienced not at all, and 5 = symptom experienced all the time. A score on the K10 <30, with at least two symptoms endorsed, was used to determine inclusion. The K10 was also used as a pre and post-intervention measure and follow-up measure of global psychological distress. The K10 has high levels of discriminant and criterion validity (61), as well as convergent validity with other measures of psychological distress (62). It also consistently shows very good levels of internal reliability as measured by Cronbach's alpha (63).

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (64) was also used to screen and determine eligibility into the pilot. The PCL-5 comprises 20 items with 5-point Likert response options, where 0 = symptom experienced not at all, and 4 = symptom experienced extremely. A score <33, with at least two symptoms endorsed was used to determine inclusion. The PCL-5 was also used as a pre and post-intervention and follow-up measure of posttraumatic stress symptoms. The PCL-5 has demonstrated high levels of internal consistency, as well as convergent, discriminant, and structural validity (65).

Impairment was measured using a single-item question developed by the SOLAR project team to provide an assessment of functional impairment in major life areas, including work or study, social activities, relationships, tasks of daily care, or other area (i.e., How much did the things you describe cause you distress and affect your ability to function in your work, your relationships with other people, and in other important areas of your life?). The item was rated using a ten-point Likert response scale, where 0 = none and 10 = extreme. This item was also used as a pre and post-intervention and follow-up measure of impairment. Participants were only included in the pilot if they met screening eligibility according to K10 and PCL-5 thresholds, in addition to endorsement of the impairment item.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus 7 (MINI Plus 7) (66) was used as a diagnostic screening tool to exclude participants with a psychiatric diagnosis from the pilot. The MINI Plus 7 is a clinical assessment tool that assesses the presence of psychiatric disorders using DSM-5 symptom criteria, rated using a dichotomous Yes/No response option. The following modules were employed: (1) PTSD, (2) major depression, (3) panic disorder, (4) agoraphobia, (5) social anxiety disorder, (6) general anxiety disorder, (7) alcohol use disorder, and (8) substance use disorder. The MINI has strong psychometric properties, with good inter-rater and test–retest reliability (66). Specificity is above .70 for all diagnoses used in this study, and sensitivity is above .70 for all modules used except for agoraphobia (66).

The Psychological Outcome Profiles instrument (PSYCHLOPS) (67) was used to measure participant-generated outcomes. It comprises four items that assess outcomes generated by the client on main problems they are presently experiencing, functioning, and wellbeing, as well as how much clients are affected by the problems they are experiencing. The PSYCHLOPS was used to assess outcomes perceived as important by participants regarding their difficulties, and as a measure of change pre and post-intervention and at follow-up. The PSYCHLOPS is sensitive to clinical change after therapy and has satisfactory levels of internal reliability, as well as convergent, concurrent, and construct validity (68).

Assessment of feasibility concerned the achievability of training frontline disaster workers without prior formal mental health training to deliver the SOLAR program following a 2-day workshop. This was determined by changes in pre-post training in coaches' knowledge of the intervention, which was assessed using a 14-item multiple choice questionnaire (four response options for each item), and by changes in coaches' confidence in providing the intervention, which was assessed using an 8-item questionnaire rated on a 5-point scale, where 0 = not at all confident and 4 = very confident. Outcome criteria for feasibility was defined as a minimum of 80% correct in the knowledge items, and a minimum of 70% in confidence.

The acceptability of SOLAR was assessed by the number of sessions completed by participants and participants' responses to two, open-ended questions included in a self-report questionnaire at post-intervention assessment, (i) ‘How useful did you find the SOLAR program overall?', (ii) ‘Would you recommend this program to others struggling after a disaster?'.

Safety was determined by monitoring for adverse events and assessing symptom measure trajectories from pre to post-intervention and at three-month follow-up. The K-10 (61) was used to assess psychological distress, the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 [PCL-5, (65)] was used to assess posttraumatic stress symptoms, and the Psychological Outcomes Profiles [Psychlops, (69)] was used to assess functioning.

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to examine change in coaches' knowledge of the intervention and confidence in delivering it pre to post-training. Repeated measures effect size estimates (dRM) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were produced to quantify the magnitude of participant within-group change in each outcome, from (a) pre to post-intervention, and (b) post-intervention to follow-up. These were based on formulas for the single-group pretest–posttest design, which standardize the sample mean change by variability in change scores (70). Data preparation was conducted in SPSS Version 23, while the dRM estimates were produced in Program R (version 3.1.3) using the Package ‘effsize’ (4). Individual trajectories were also produced using the Package ‘ggplot2’ (71), and were displayed graphically to contextualize the group estimates and explore the variability in individual scores over time.

Analyses revealed a significant improvement in coaches' knowledge of the program from pre-training (Mdnpre = 11) to post-training (Mdnpost = 14; Z = −3·20, p = 0·001), and a significant improvement in coaches' confidence to deliver the program (Mdnpre = 24, Mdnpost = 35, Z = −3·18, p = 0·001). All coaches met the readiness criteria.

All participants determined to be eligible for the program agreed to participate. Of these 15 participants, all completed the total number of sessions, suggesting a high level of program acceptability. Six participants completed a self-report questionnaire concerning their satisfaction with the program. Of these, all reported that they had found the program useful, and that they would recommend the program to other disaster survivors.

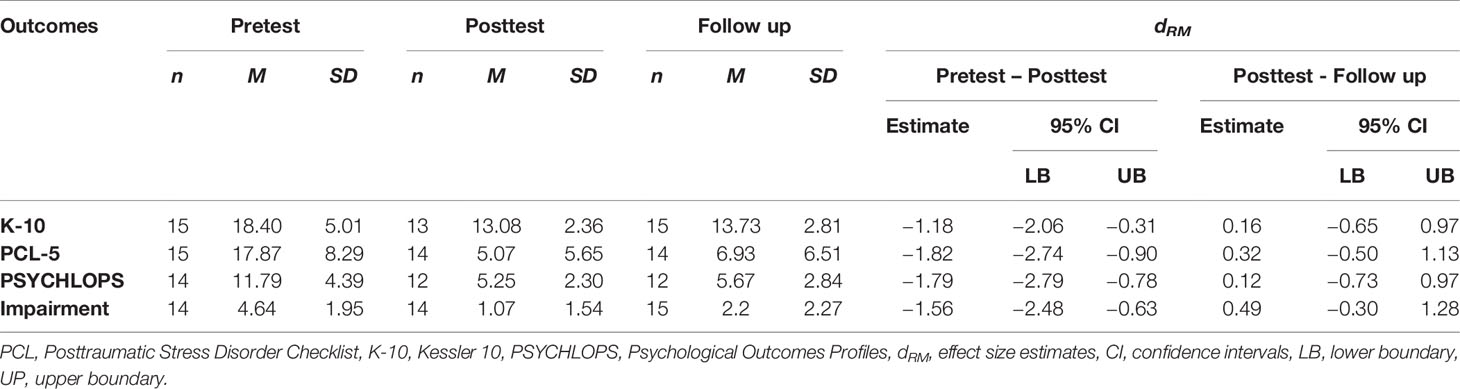

No adverse events were reported and symptoms did not deteriorate in the three months after the SOLAR program. Participants' scores on the K-10, PCL-5, and PSYCHLOPS are shown in Table 3, which includes descriptive statistics (Means, SDs) at pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up, as well repeated measures effect size estimates (dRM). Missing data was managed through pairwise deletion.

Table 3 Symptom score statistics and repeated measures effect size estimates (dRM) on K10, PCL-5 and PSYCHLOPS from pre-test to post-test and from post-test to follow up.

Descriptive statistics indicated reductions in mean scores for all outcomes from pre to post-intervention, along with a slight increase from post-intervention to follow-up. These interpretations were supported by the dRM estimates, which corresponded to large improvements over time and across the intervention (particularly for the PCL-5 and PSYCHLOPS), and minimal increase of symptoms over follow-up. Although inferences should be made cautiously given the small sample size, the 95% CIs for each estimate of dRM from pre to post-intervention excluded zero, and are therefore consistent with statistically significant effects at the p <0.05 criterion level. In contrast, the comparable estimates suggested negligible-to-small changes from post-intervention to follow-up, while the 95% CIs all included zero (which was thus a plausible value).

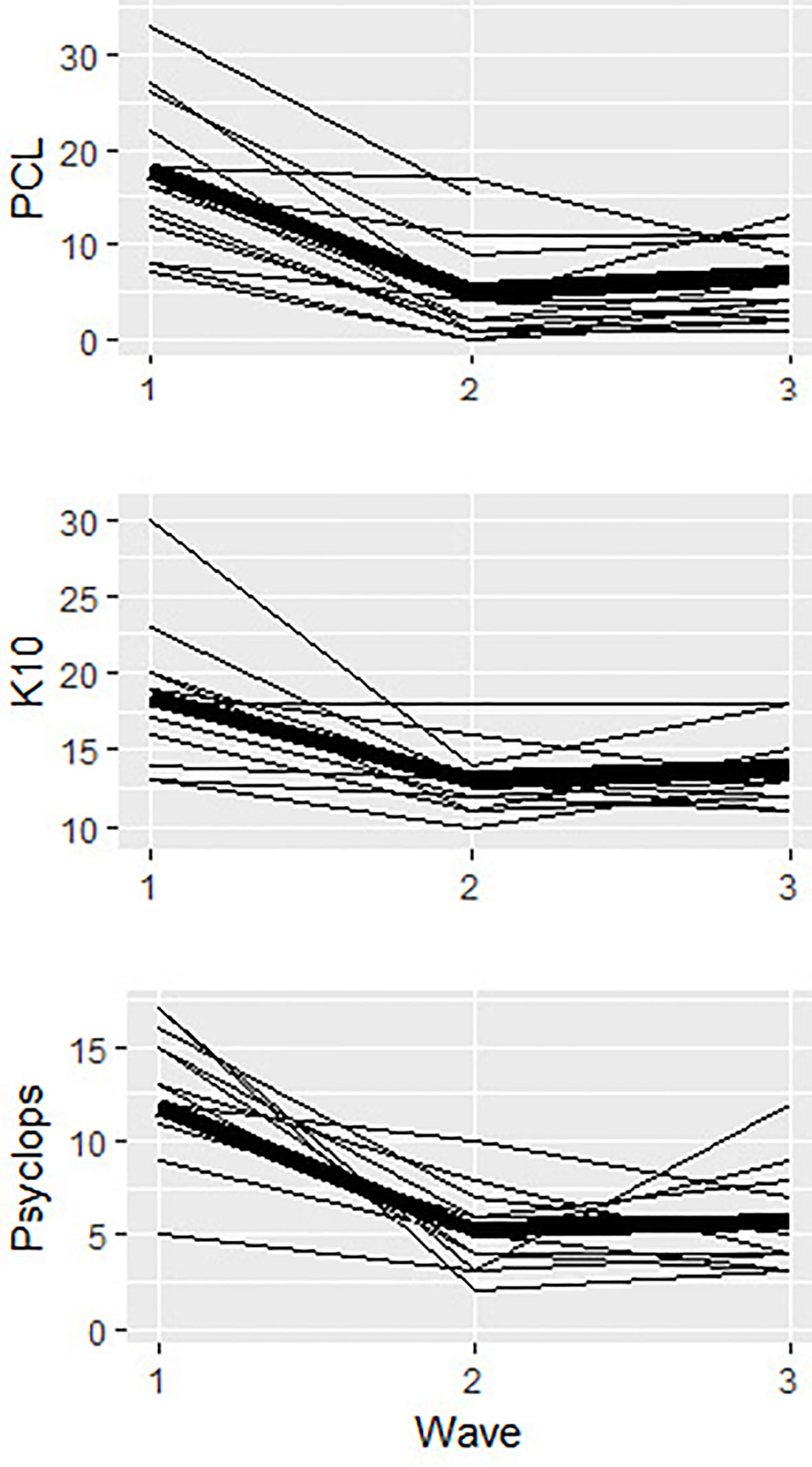

Figure 3 shows plots of individual trajectories for each outcome measure, with the mean trajectory displayed in bold. As shown, there was discernible variability in change over time, but all trajectories suggested either stable or declining scores from pre to post-intervention. While some trajectories indicated subsequent increases, these slopes were generally modest and reflect follow-up scores that were all still well below pre-intervention levels. As such, there is evidence that the SOLAR program was not associated with a decline in symptom scores.

Figure 3 Plots of inidividual trajectories for all outcome measures (K10, PCL-5, Psychlops) across pre-intervention (wave 1), post-intervention (wave 2) and follow-up (wave 3). The main trajectory for each otucome is in bold.

There is an identified need for a brief intervention that targets individuals who experience difficulties adjusting following disaster and trauma but do not qualify for a formal mental health diagnosis. SOLAR was developed through an international collaboration and informed by existing theoretical and empirical studies regarding mechanisms central to trauma recovery and evidence of effective posttraumatic therapeutic approaches. This study provides preliminary evidence that the SOLAR program is an accessible, brief, and scalable psychosocial intervention that can be delivered by trained frontline workers, including volunteers, professional, and paraprofessional health or disaster workers. While further, more rigorous studies are required, this study suggests that SOLAR has the potential to be useful for individuals with adjustment difficulties following trauma, and holds promise as a complement to existing universal and standard treatment interventions in a strategic, stepped model of mental healthcare. It offers a unique emotional processing component to assist with emotional reactions associated with a traumatic event such as disaster.

Our findings provide preliminary evidence that the SOLAR program can be safely delivered by trained, non-mental health specialists after two days of training delivered by appropriately experienced mental health clinicians. After training, coaches demonstrated improvements in knowledge and confidence in delivering the intervention, and were able to implement the intervention in a safe manner that was acceptable to participants, providing support for the intervention's feasibility. Our findings demonstrate that SOLAR was implementable within existing, diverse, disaster support services in community health and disaster management sectors.

The pilot also provided preliminary evidence that SOLAR is acceptable to disaster survivors in the Australian context, with all participants who were eligible to participate completing all five sessions of SOLAR, and all who responded to open-ended questions concerning program satisfaction stating that the program was useful and that they would recommend it to other disaster survivors. Our findings demonstrated the safety of SOLAR in this particular setting, with no findings of adverse events, and all symptom trajectories trending in a positive direction. In support of the program's efficacy, pre to post-intervention changes demonstrated significant decreases in posttraumatic stress and distress following SOLAR, as well as significant improvements in functioning, with maintenance of improvements over time. In combination, the results warrant further piloting of SOLAR in other post-disaster settings and the conduct of randomized control trials to determine program efficacy.

The findings of the study should be considered alongside the study limitations, which include the small sample size. As such the generalizability of these findings are unknown. We could not look at how gender or culture influenced treatment response, nor did we ask coaches how easy/difficult they found delivering the intervention (which would have informed feasibility). Additionally, the follow-up assessments were conducted three months following the program, and therefore it cannot be determined whether changes that were reported by participants were sustained beyond this time point. Finally, we used traditional formulae for calculation of the dRM, which may overestimate the magnitude of effects given instances of unequal variances.

SOLAR represents a brief, disaster-focused psychosocial intervention that includes a multi-faceted set of intervention components. It offers an important addition to a disaster mental healthcare response. The current findings suggest that SOLAR is feasible, acceptable, and can be safely administered by non-mental health professionals. Phase III randomized control trials are required to further test its efficacy in other disaster or trauma exposed settings, and further studies are required to test the scalability of the intervention.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Melbourne Health Sciences Human Ethics Sub-Committee, University of Melbourne (HSHEC 1647794). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MO'D, AP, DF, RB, JB, SB, WB, AC, MC, DG, NG, BM, AM, CM, JR, PS, JU, PW, SW, and RW contributed to the development of the intervention and designed the evaluation methodology. MO'D, WL, DF, and RB designed the study and interpreted the findings. MO'D, WL, JF, KG, and DF drafted and revised the manuscript. SC conducted the statistical analyses. MO'D, AP, DF, RB, JB, SB, WB, AC, MC, DG, NG, BM, AM, CM, JR, PS, JU, PW, SW, and RW provided expert advice to the manuscript. All authors approved the final version published.

This project was funded by Princes Trust Australia, the Australian Commonwealth Government Departments of Defence, Veterans' Affairs, and Health, the University of Melbourne, the Returned Service League (Queensland and Victoria), and the National Health and Medical Research Council Program under Grant Number 1073041.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We acknowledge the funders in addition to our partners in the pilot, the Northern Health Network, Country SA Primary Health Network, and the Australian Red Cross. We also wish to acknowledge the Pinery and Sampson Flat communities of South Australia where the SOLAR pilot trial was held, and particularly the coaches and participants of the SOLAR program. We also acknowledge Dr. Naomi Ralph, and Dr. Jason Blunt who were involved in various aspects of the SOLAR piloting process.

1. North CS, Pfefferbaum B. Mental health response to community disasters: a systematic review. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc (2013) 310(5):507–18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.107799

2. Reifels L, Mills K, Dückers MLA, O'Donnell ML. Psychiatric epidemiology and disaster exposure in Australia. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci (2017) 28(3):310–20. doi: 10.1017/S2045796017000531

3. Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An emirical review of the empirical literature, 1981 - 2001. Psychiatry (2002) 65:207–39. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173

4. Torchiano M. (2016). Effsize: Efficient effect size computation. R package version 0.6.1. , http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=effsize.

5. NATO Joint Medical Committee. Psychosocial Care for People Affected by Disaster and Major Incidents: A Model for Designing, Delivering and Managing Psychosocial Services for People Involved in Major Incidents, Conflict, Disasters and Terrorism. NATO (2008). Retrieved from the Council of Europe website: https://www.coe.int

6. McCabe OL, Everly GS Jr., Brown LM, Wendelboe AM, Abd Hamid NH, Tallchief VL, et al. Psychological first aid: a consensus-derived, empirically supported, competency-based training model. Am J Public Health (2014) 104(4):621–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301219

7. Ruzek JI, Brymer MJ, Jacobs AK, Layne CM, Vernberg EM, Watson PJ. Psychological First Aid. J Ment Health Couns (2007) 29(1):17–49. doi: 10.17744/mehc.29.1.5racqxjueafabgwp

8. Shultz JM, Forbes D. Psychological First Aid. Disaster Health (2014) 2(1):3–12. doi: 10.4161/dish.26006

9. Dieltjens T, Moonens I, Van Praet K, De Buck E, Vandekerckhove P. A Systematic Literature Search on Psychological First Aid: Lack of Evidence to Develop Guidelines. PloS One (2014) 9(12):e114714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114714

10. Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson JI, Cohen JA, Crow BE, Foa EB, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. J Traumatic Stress (2010) 23(5):537–52. doi: 10.1002/jts.20565

11. Kessler RC, Galea S, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Ursano RJ, Wessely S. Trends in mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Mol Psychiatry (2008) 13(4):374–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002119

12. O'Donnell ML, Varker T, Creamer M, Fletcher S, McFarlane A, Silove D, et al. An exploration of delayed onset posttraumatic stress disorder following severe injury. Psychosomatic Med (2013) 75:68–75. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182761e8b

13. O'Donnell ML, Alkemade N, Creamer M, McFarlane A, Silove D, Bryant R, et al. A longitudinal study of adjustment disorder after trauma exposure. Am J Psychiatry (2016) 173(12):1231–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010071

14. Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, Charlson FJ, Degenhardt L, Dua T, et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet (London England) (2016) 387(10028):1672–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00390-6

15. Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK, Anand A, Chorpita BF, Patel V. Psychological Treatments for the World: Lessons from Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Annu Rev Clin Psychol (2017) 13:149–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045217

16. Clark DM. Implementing NICE guidelines for the psychological treatment of depression and anxiety disorders: The IAPT experience. Int Rev Psychiatry (2011) 23(4):318–27. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.606803

17. Clark DM. Realizing the Mass Public Benefit of Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies: The IAPT Program. Annu Rev Clin Psychol (2018) 14:159–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084833

18. Dawson KS, Bryant RA, Harper M, Kuowei Tay A, Rahman A, Schafer A, et al. Problem Management Plus (PM+): A WHO transdiagnostic psychological intervention for common mental health problems. World Psychiatry (2015) 14(3):354–7. doi: 10.1002/wps.20255

19. World Health Organization. Problem Management Plus (PM+): Individual psychological help for adults impaired by distress in communities exposed to adversity. (Generic field-trial version 1.1). Geneva: WHO (2018).

20. Rahman A, Hamdani SU, Awan NR, Bryant RA, Dawson KS, Khan MF, et al. Effect of a multicomponent behavioral intervention in adults impaired by psychological distress in a conflict-affected area of Pakistan: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc (2016) 316(24):2609–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17165

21. Bryant RA, Schafer A, Dawson KS, Anjuri D, Mulili C, Ndogoni L, et al. Effectiveness of a brief behavioural intervention on psychological distress among women with a history of gender-based violence in urban Kenya: A randomised clinical trial. PloS Med (2017) 14(8):e1002371–e1002371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002371

22. National Centre for PTSD, National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2009). Skills for Psychological Recovery: Field operations guide. Retrieved from the National Center for PTSD, U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website: https://www.ptsd.va.gov

23. Forbes D, O'Donnell ML, Bryant RA. Psychosocial recovery following community disaster: An international collaboration. Aust New Z J Psychiatry (2016) 51(7):660–2. doi: 10.1177/0004867416679737

24. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. (2008). Retrieved from the Medical Research Council website: https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/.

25. Bisson JI, Brayne M, Ochberg FM, Everly GS. Early psychosocial intervention following traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164(7):1016–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1016

26. Briere JN, Scott C. Principles of Trauma Therapy: A Guide to Symptoms, Evaluation, and Treatment (DSM-5 update). Thousand Oaks, United States: Sage Publications (2014).

27. Tol WA, Barbui C, Galappatti A, Silove D, Betancourt TS, Souza R, et al. Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings: Linking practice and research. Lancet (2011) 378(9802):1581–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61094-5

28. King AP, Erickson TM, Giardino ND, Favorite T, Rauch SAM, Robinson E, et al. A pilot study of group mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for combat veterancs with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Depression Anxiety (2013) 30(7):638–45. doi: 10.1002/da.22104

29. Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Treatment of individuals who have been raped: Foa & Rothbaum model. In: Foa EB, Rothbaum BA, editors. Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. Guilford Press: New York (1998).

30. Jorm AF, Morgan AJ, Hetrick SE. Relaxation for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2008) 4:CD007142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007142.pub2

31. Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, Gillihan SJ, Foa EB. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev (2010) 30(6):635–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.007

32. Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Guthrie RM, Dang ST, Nixon RDV. Imaginal exposure alone and imaginal exposure with cognitive restructuring in treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consulting Clin Psychol (2003) 71(4):706. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.706

33. Zang Y, Hunt N, Cox T. Adapting narrative exposure therapy for Chinese earthquake survivors: A pilot randomised controlled feasibility study. BMC Psychiatry (2014) 14:262. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0262-3

34. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ. Guidelines for treatment of PTSD. J Traumatic Stress: Off Publ Int Soc Traumatic Stress Stud (2000) 13(4):539–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1007802031411

35. Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. J Consulting Clin Psychol (2002) 70(4):867. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.867

36. Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Dang ST, Sackville T, Basten C. Treatment of acute stress disorder: A comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. J Consulting Clin Psychol (1998) 66(5):862. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.5.862

37. Shalev AY, Ankri Y, Israeli-Shalev Y, Peleg T, Adessky R, Freedman S. Prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder by early treatment: Results from the Jerusalem Trauma Outreach And Prevention study. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2012) 69(2):166–76. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.127

38. Ehlers A, Bisson J, Clark DM, Creamer M, Pilling S, Richards D, et al. Do all psychological treatments really work the same in posttraumatic stress disorder? Clin Psychol Rev (2010) 30(2):269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.001

39. Kaniasty K. Predicting social psychological well-being following trauma: The role of postdisaster social support. psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy (2012) 4(1):22–33. doi: 10.1037/a0021412

40. Rubin DC, Berntsen D, Bohni MK. A memory-based model of posttraumatic stress disorder: Evaluating basic assumptions underlying the PTSD diagnosis. psychol Rev (2008) 115(4):985–1011. doi: 10.1037/a0013397

41. Norris FH, Maker CK, Murphy AD, Kaniasty K. Social support mobilization and deterioration after Mexico's 1999 flood: Effects of context, gender, and time. Am J Community Psychol (2005) 36(1-2):15–28. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6230-9

42. Simeon D, Greenberg J, Nelson D, Schmeidler J, Hollander E. Dissociation and posttraumatic stress 1 year after the World Trade Center disaster: Follow-up of a longitudinal survey. J Clin Psychiatry (2005) 66(2):231–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0212

43. Benight CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav Res Ther (2004) 42(10):1129–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008

44. Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Gold J, Bucuvalas M, Kilpatrick D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in Manhattan, New York City, after the September 11th terrorist attacks. J Urban Health: Bull New York Acad Med (2002) 79(3):340–53. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.3.340

45. Litz B, Gray MJ, Bryant RA, Adler AB. Early intervention for trauma: Current status and future directions. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract (2002) 9(2):112–34. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.2.112

46. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev (2007) 27:318–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001

47. van't Hof E, Cuijpers P, Waheed W, Stein DJ. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety disorders in low- and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis. African J Psychiatry (2011) 14(3):200–7. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v14i3.2

48. Hamblen JL, Norris FH, Pietruszkiewicz S, Gibson LE, Naturale A, Louis C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for postdisaster distress: A community based treatment program for survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res (2009) 36(3):206–14. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0213-3

49. Somer E, Tamir E, Maguen S, Litz BT. Brief cognitive-behavioral phone-based intervention targeting anxiety about the threat of attack: A pilot study. Behav Res Ther (2005) 43(5):669–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.05.006

50. Gillespie K, Duffy M, Hackmann A, Clark DM. Community based cognitive therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder following the Omagh bomb. Behav Res Ther (2002) 40(4):345–57. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00004-9

51. Najavits LM. seeking safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York, US: Guilford Press (2002) p. xiv, 401–xiv, 401.

52. Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. J Consulting Clin Psychol (1992) 60(5):748–56. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.748

53. Mulligan K, Fear NT, Jones N, Wessely S, Greenberg N. Psycho-educational interventions designed to prevent deployment-related psychological ill-health in Armed Forces personnel: a review. psychol Med (2011) 41(04):673–86. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000125X

54. Howard JM, Goelitz A. Psychoeducation as a response to community disaster. Brief Treat Crisis Interv (2004) 4(1):1. doi: 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhh001

55. Sahin NH, Yilmaz B, Batigun A. Psychoeducation for children and adults after the Marmara earthquake: An evaluation study. Traumatology (2011) 17(1):41–9. 1534765610395624. doi: 10.1177/1534765610395624

56. Oflaz F, Hatipoglu S, Aydin H. Effectiveness of psychoeducation intervention on post-traumatic stress disorder and coping styles of earthquake survivors. J Clin Nurs (2008) 17(5):677–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02047.x

57. Gray MJ, Litz B. Behavioral interventions for recent trauma: Empirically informed practice guidelines. Behav Modif (2005) 29(1):189–215. doi: 10.1177/0145445504270884

58. Lewinsohn PM. A behavioral approach to depression, in The Psychology of Depression: Contemporary Theory and Research. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons (1974) p. xvii, 318–xvii, 318.

59. Hobfoll SE, Watson PJ, Bell CC, Bryant RA, Brymer MJ, Friedman MJ, et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry (2007) 70(4):283–315. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.4.283

60. Kessler RC, Barker P, Colpe L, Epstein J, Gfroerer J, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2003) 60(2):184–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184

61. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. psychol Med (2002) 32(6):959–76. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074

62. Cornelius BL, Groothoff JW, van der Klink JJ, Brouwer S. The performance of the K10, K6 and GHQ-12 to screen for present state DSM-IV disorders among disability claimants. BMC Public Health (2013) 13(1):128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-128

63. Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Zamorski MA, Colman I. The psychometric properties of the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) in Canadian military personnel. PloS One (2018) 13(4):e0196562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196562

64. Weathers FW, Litz B, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. In: . Annual convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. San Antonio, TX: San Antonio, TX (1993).

65. Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. J Traumatic Stress (2015) 28(6):489–98. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059

66. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry (1998) 59(20):22–3.

67. Ashworth M, Shepherd M, Christey J, Matthews V, Wright K, Parmentier H, et al. A client-generated psychometric instrument: The development of ‘PSYCHLOPS'. Couns Psychother Res (2004) 4(2):27–31. doi: 10.1080/14733140412331383913

68. Ashworth M, Robinson SI, Godfrey E, Shepherd M, Evans C, Seed P, et al. Measuring mental health outcomes in primary care: the psychometric properties of a new patient-generated outcome measure,PSYCHLOPS' (psychological outcome profiles'). Prim Care Ment Health (2005) 3(4):261–70.

69. Alves P, Sales M, Ashworth M. Personalising the evaluation of substance misuse treatment: A new approach to outcome measurement. Int J Drug Policy (2014) 26(4):333–5. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.11.014

70. Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. psychol Methods (2002) 7(1):105. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.105

Keywords: trauma, adjustment disorder, posttraumatic stress, disaster, psychosocial intervention, brief intervention, sub-clinical, sub-syndromal

Citation: O'Donnell ML, Lau W, Fredrickson J, Gibson K, Bryant RA, Bisson J, Burke S, Busuttil W, Coghlan A, Creamer M, Gray D, Greenberg N, McDermott B, McFarlane AC, Monson CM, Phelps A, Ruzek JI, Schnurr PP, Ugsang J, Watson P, Whitton S, Williams R, Cowlishaw S and Forbes D (2020) An Open Label Pilot Study of a Brief Psychosocial Intervention for Disaster and Trauma Survivors. Front. Psychiatry 11:483. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00483

Received: 27 November 2019; Accepted: 12 May 2020;

Published: 26 June 2020.

Edited by:

Rakesh Pandey, Banaras Hindu University, IndiaReviewed by:

Anubhuti Dubey, Deen Dayal Upadhyay Gorakhpur University, IndiaCopyright © 2020 O'Donnell, Lau, Fredrickson, Gibson, Bryant, Bisson, Burke, Busuttil, Coghlan, Creamer, Gray, Greenberg, McDermott, McFarlane, Monson, Phelps, Ruzek, Schnurr, Ugsang, Watson, Whitton, Williams, Cowlishaw and Forbes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meaghan Louise O'Donnell, bW9kQHVuaW1lbGIuZWR1LmF1

†ORCID: Meaghan Louise O'Donnell, orcid.org/0000-0003-4349-0022

Winnie Lau, orcid.org/0000-0003-2366-2464

Jonathan Bisson, orcid.org/0000-0001-5170-1243

Mark Creamer, orcid.org/0000-0001-9986-3591

Debbie Gray, orcid.org/0000-0002-8448-6858

Neil Greenberg, orcid.org/0000-0003-4550-2971

Brett McDermott, orcid.org/0000-0002-6639-1767

Alexander C. McFarlane, orcid.org/0000-0002-3829-9509

Andrea Phelps, orcid.org/0000-0002-9235-8012

Josef I. Ruzek, orcid.org/0000-0003-4099-6431

Paula P. Schnurr, orcid.org/0000-0002-6195-716X

Sean Cowlishaw, orcid.org/0000-0002-8523-3713

David Forbes, orcid.org/0000-0001-9145-1605

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.