- Department of Neurology and Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt

Introduction: Alexithymia is characterized by difficulties in describing feelings. Many studies have shown that there is a relation between alexithymia and different types of addictions. Nowadays, smartphone addiction is proposed to be a global problem. The current study focuses on the rates of alexithymia and its association with smartphone addiction in an Egyptian university.

Materials and Methods: This is a cross-sectional study that was conducted in Ain Shams University. A sample of 200 university students was surveyed using Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) and Smartphone Addiction Scale–Short Version (SAS-SV).

Results: The results showed that 44 students (22%) had alexithymia. It was also found that around one third of the sample (N=65, 32.5%) met the criteria of smartphone addiction. There was a strong association between alexithymia and smartphone addiction (OR=4.33, 95% CI 2.15–8.74, p= < 0.001).

Conclusion: This study supports existing literature indicating the strong association between alexithymia and smartphone addiction.

Introduction

Alexithymia is characterized by difficulties describing feelings and a decreased ability to differentiate between emotions and physical sensations (1). It was first studied in patients with psychosomatic disorders (2). Those suffering from alexithymia are unable to verbalize their own emotions and/or the emotions of others. Alexithymia has been linked to difficulties in facing and dealing with stressful conditions (3), anxiety and depression (4), lower self-esteem, dissociative experiences (5), low relationship satisfaction (6), and difficulties in building and maintaining healthy interpersonal relationships (7).

Moreover, many studies have shown that there is a relation between alexithymia and different types of addictions; including opioid use disorder (8), alcohol use disorder (9), and behavioral addictions like internet addiction (10).

On the other hand, smartphones are devices capable of processing information that include access to Internet and social networks, messaging, and multimedia besides their main function as a tool for communication (11). As individuals almost always have their smartphones with them, and they can use their smartphones multiple times during the day, smartphone use may become an automatic behavior that is performed with little thinking (12). Therefore, a great concern has emerged that high frequency smartphone use may suggest that smartphones could become a behavioral addiction. However, the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) does not recognize smartphone addiction as a disorder (13).

Individuals with symptoms of smartphone addiction tend to bring their phone with them wherever they are and think about their phone even if they cannot use it, which ultimately influences daily tasks. The proposed criteria to determine whether an individual suffer from smartphone dependence consists of four main components: compulsive phone use, tolerance witnessed by longer and more intense use, withdrawal symptoms, and functional impairment by interfering with other life activities (14).

Despite the advantages of providing information and communication opportunities (15) and not yet being officially recognized as a disorder (13), smartphone overuse or addiction is proposed to have negative impacts on health. Physical health problems such as visual impairment, musculoskeletal problems (16, 17), ear pain, headache, and sleep disorders, (18, 19) have been suggested to be related to it. Moreover, some mental health problems have also been linked to smartphones addiction such as depression and anxiety (20).

On the other hand, as individuals with alexithymia complain of having difficulties in identifying and describing their feelings, thus, they may resort to internet use to manage them (21). With the rapid development of smartphones, internet use became easier and more accessible (22). Thus, the use of smartphone and even dependence on it might be higher among this group. Few previous studies have investigated the relation between alexithymia and smartphone addiction and the results were interesting. Alexithymia was positively correlated with mental health problems and smartphone addiction (23–25). Yet, to our knowledge, no studies have explored such relation in Arab countries.

Furthermore, many smartphone addiction studies were focused on college students. They may spend much time on “interaction” with the mobile phone which may affect their daily life. Moreover, researchers suggest that the higher the degree of mobile phone addiction, the greater the likelihood that college students’ academic performance will be affected (26). Hence, the current study focuses on alexithymia and its relation to smartphone addiction in students at an Egyptian university.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study that was conducted in Ain Shams University, which is in Cairo, Egypt, from April to August 2019. The study obtained the approval of the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of Faculty of Medicine (approval no. FMASU: R 45/2019). The sample size was calculated to be 200 students setting alpha error at 5% and confidence interval width at 0.1 (margin of error at 5%). Prevalence of alexithymia among university students was shown to be 12.5% in a previous study (27). The sample size was calculated taking in account 10% drop out rate. Students were recruited from campus and asked to complete a questionnaire including some demographic data and two scales. A total of 200 students participated in the study. The participants were requested to fill in a traditional paper-and-pencil questionnaire. They were informed about the aim of the study and that by filling in the questionnaire they consent to take part. It took the respondents approximately 15 min to complete the questionnaire.

Measures

Demographic information collected includes age, sex, faculty, and academic year. The questionnaire included two scales: Toronto Alexithymia Scale and Smartphone Addiction Scale–Short Version.

Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20), Arabic Version

Toronto Alexithymia Scale, (28) Arabic Version (29) was used to measure alexithymia. TAS is the most used and extensively validated measure for alexithymia (30). TAS consists of 20 items that is divided into three subscales: difficulty identifying feelings (DIF) with seven items, difficulty describing feelings (DDF) with five items, and externally oriented thinking (EOT) with eight items. TAS is five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree,” with five items negatively keyed. The total score is calculated by summing the responses of all the items with a range of 20–100. The cutoff point is 60 and people with score of more than 60 are considered as having alexithymia. People with scores between 52 and 60 are considered to have possible alexithymia. People with a score of 51 or below are considered free of alexithymia. This tool has been translated to Arabic and back translated to the original language by a panel of experts following the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for translation of instruments. The scale showed good internal consistency reliability, test–retest reliability, convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. In this study, we arranged the sample into two groups using the score of 60 as a cutoff point for having alexithymia or not.

The Smartphone Addiction Scale–Short Version (SAS-SV), Arabic Version

The SAS-SV is a validated scale which was originally designed in South Korea but published in English (31, 32). This scale is a shortened version of the original 40 itemed scale. It is a ten itemed questionnaire used to assess levels of smartphone addiction. Participants are asked to rate on a dimensional scale how much each statement relates to them. The total score ranges from 10 to 60. This scale has been used in various research across different cultures including (33, 34). The scale is very quick and easy to use, there are no reverse scores involved. Smartphone addiction cut-off values of ≥ 31 and ≥ 33 for male and female participants, respectively, were applied as suggested by Kwon et al. (31, 32). Arabic version of SAS-SV used in this study was translated and validated by Sfendla et al. (35) and showed excellent reliability based on Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.94).

Data Analysis

The SPSS 22.0 was used in our study for statistical analyses. The significance level was set at 0.05. Chi square and T-test were used to check the differences regarding alexithymia and smartphone addiction among the demographic features. Odds ratio was used to express the magnitude of the association between alexithymia and smartphone addiction.

Results

Demographic Features of the Participants

Data were collected from 85 males (42.5%) and 115 females (57.5%). The age of the participants ranged from 17 to 27 years with a mean age of 21.225 ± 1.986. Eighty-four students (42%) were enrolled in practical faculties (i.e. medicine, engineering, etc.) and 116 (58%) students were enrolled in theoretical faculties (i.e. law, commerce, etc.). Regarding academic years, 21 students (10.5%) were enrolled in the first year, 38 students (19%) were enrolled in second year, 48 students were enrolled in third year (24%), 72 students (36%) were enrolled in fourth year, 17 students (8.5%) were enrolled in fifth year, and only 4 students (2%) were enrolled in sixth year.

Alexithymia According to TAS-20 Scores

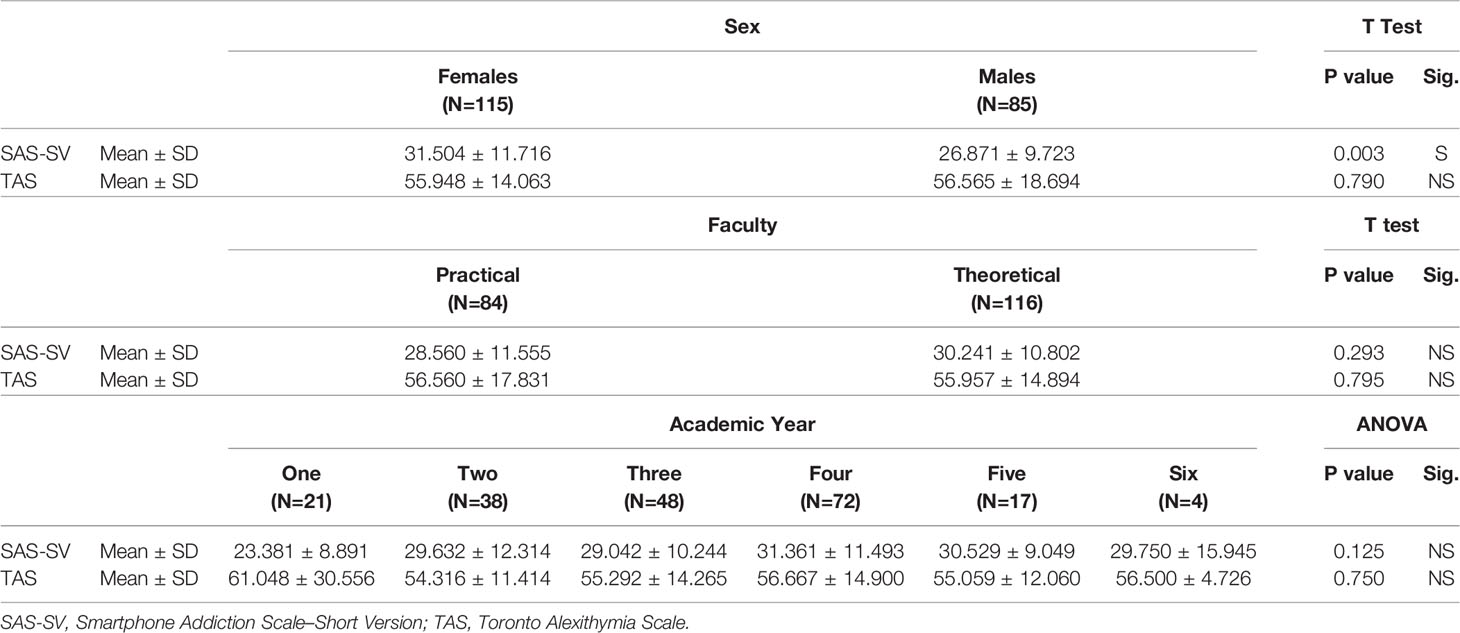

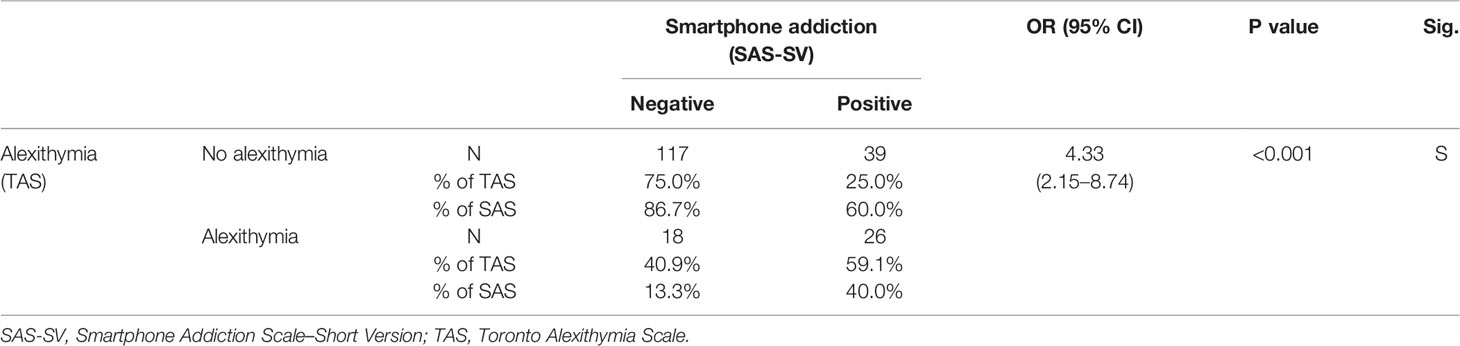

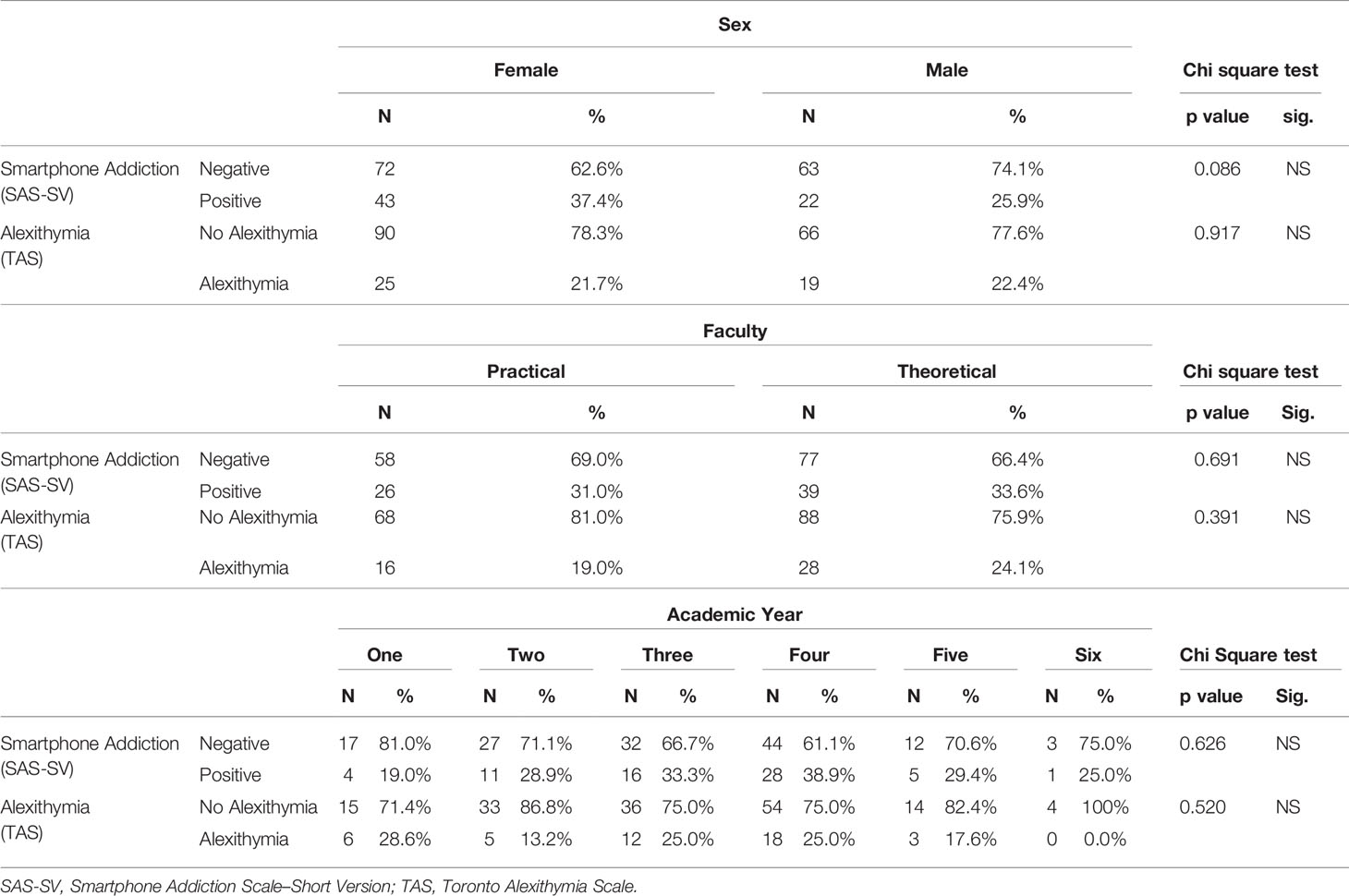

Alexithymia was measured by TAS-20. In this study the cutoff score of 60 was used to differentiate those with and without alexithymia. The results showed that 44 students (22%) had alexithymia, while the remaining 78% were considered negative for it. There was no significant difference between males and females (p=0.917), between practical and theoretical faculties (p=0.391), nor academic year (p= 0.520) regarding alexithymia rates as shown in Table 1. There were also no significant differences between males and females (p=0.790), type of faculties (p=0.795), nor different academic years regarding (p=0.750) the scores of TAS as shown in Table 2.

Table 1 Comparing rates of smartphone addiction and alexithymia according to sex and type of faculty.

Smartphone Addiction According to SAS-SV Scores

Smartphone addiction was measured by SAS-SV scale and results showed that around one third of the sample (N=65, 32.5%) met the criteria of smartphone addiction. There was no significant difference between males and females (p=0.086) nor practical and theoretical faculties (p=0.691) regarding smartphone addiction rate as shown in Table 1. No significant differences in SAS-SV scores were found between faculties (p=0.293) nor different academic years (p=0.125), however, females had significantly higher scores on SAS-SV (p=0.003) as shown in Table 2.

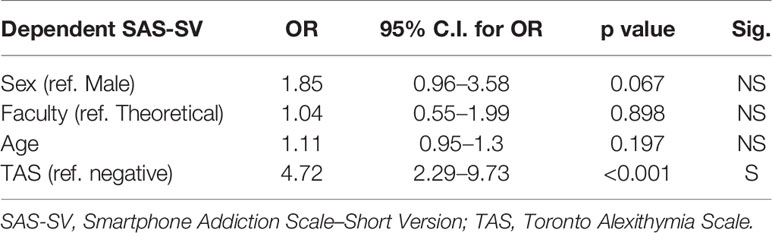

Relation Between Alexithymia and Smartphone Addiction

There was a strong association between alexithymia and smartphone addiction (OR=4.33, 95% CI: 2.15–8.74, p= < 0.001) as shown in Table 3. Also, logistic regression analysis for predictors of smartphone addiction only showed presence of alexithymia as a significant factor as shown in Table 4.

Discussion

The term alexithymia was introduced by Peter Sifneos in 1972 (1) and was originally described in patients with psychosomatic complaints (36). The present study addressed the rates of alexithymia and its relation with smartphone addiction among a sample of university students. To our knowledge this is the first study to address the topic in Arab countries and one of the few worldwide.

This study showed that the rate of alexithymia for the whole sample was 22%, and almost the same in both sexes (21.7% of males and 22.4% of females). This rate is comparable to alexithymia rate (24.6%) among Jordanian university students (37). However, this rate is higher than rates found in western countries; 16.7% among Italian high school students (21) and 17.92% among British undergraduate students (38). This discrepancy may be explained by the cultural belief in Arab countries that emotional expression is a sign of personal weakness (39). Another explanation might be that previous research has found psychosomatic complaints to be higher in Arabic cultures (40).

On the other hand, smartphone addiction is a global problem with multiple complications that have been addressed in multiple research. This study showed smartphone addiction to be present among 32.5% of the sample. Moreover, despite being a not statistically significant difference, rate among females (37.45) was higher than males (25.9%). This rate is comparable to those found in some other studies as 28.7% in the Netherlands (41) and 25% in the United States (42). However other studies reported lesser rates as low as 6% in Italy (43) and 18.8% in Japan (44). On the other hand, the non-statistically significant gender difference of smartphone addiction is consistent with previous studies (44, 45). Yet, some studies have reported that female participants indeed have higher rates of smartphone addiction than males (46, 47).

Regarding the relationship between alexithymia and smartphone addiction, our study results showed that there is a strong association between both. This was consistent with most of previous literature (23, 24). One possible explanation of such relation is that people with alexithymia tend to regulate their emotions by various types of addictive behaviors (48). However, one study showed that individuals with alexithymia had less frequent mobile phone use (49)

Several limitations are present in this study. The cross-sectional study design could not provide the causal relationship between alexithymia and smartphone addiction so longitudinal studies are needed to address this problem. Secondly the study is based on a self-reported questionnaire, which may result in several confounding factors. Thus, a more objective data collection methods should be used to improve credibility in the future. Finally, the small sample size and the collection of data from one university could affect the generalizability of the findings. Despite that the sample size was calculated to be enough, we would recommend larger samples and recruitments from more than one university in future studies.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Committee (REC) of Ain Shams University Faculty of Medicine (approval no. FMASU: R 45/2019). Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study. II was responsible for the field work. All authors were responsible for data revision. HE and II drafted the first version. HE and ME critically revised and finalized it for publication. All authors approved and contributed to the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the students who participated in filling in this survey.

References

1. Sifneos PE. The prevalence of alexithymic characteristics in psychomatic patients. Psychother Psychosomat (1973) 22:255– 262. doi: 10.1159/000286529

2. Taylor GJ. Alexithymia: concept, measurement, and implications for treatment. Am J Psychiatry (1984) 141:725–32. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.6.725

3. Hisli Sahin N, Güler M, Basim HN. The relationship between cognitive intelligence, emotional intelligence, coping and stress symptoms in the context of type A personality pattern. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi (2009) 20(3):243–54.

4. Nekouei ZK, Doost HTN, Yousefy A, Manshaee G, Sadeghei M. The relationship of Alexithymia with anxiety-depression-stress, quality of life, and social support in Coronary Heart Disease (A psychological model). J Educ Health Promot (2014) 3:68. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.134816

5. De Berardis D, D’Albenzio A, Gambi F, Sepede G, Valchera A, Conti CM, et al. Alexithymia and its relationships with dissociative experiences and internet addiction in a nonclinical sample addiction in a nonclinical sample. CyberPsychol Behav (2009) 12(1):67–9. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0108

6. Humphreys TP, Wood LM, Parker JDA. Alexithymia and satisfaction in intimate relationships. Pers Ind Diff (2009) 46(1):43–7. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.002

7. Timoney LR, Holder MD. Correlates of alexithymia. In: Timoney LR, Holder MD, editors. Emotional processing deficits and happiness. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands (2013). p. 41–60. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7177-2_6

8. Haviland MG, Hendryx MS, Shaw DG, Henry JP. Alexithymia in women and men hospitalized for psychoactive substance dependence. Compr Psychiatry (1994) 35(2):124–8. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(94)90056-N

9. Barth F. Listening to words, hearing Feelings: links between eating disorders and alexithymia. Clin Soc Work J (2016) 44:38–46. doi: 10.1007/s10615-015-0541-6

10. Schimmenti A, Passanisi A, Caretti V, La Marca L, Granieri A, Iacolino C, et al. Traumatic experiences, alexthimia, and Internet addiction sympotoms among late adolescence: A moderated mediation analysis. Addict Behav (2017) 64:314–20. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.002

11. Statista. (2017). Number of smartphone users worldwide from 2014 to 2020. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-ofsmartphone-users-worldwide/.

12. Oulasvirta A, Rattenbury T, Ma L, Raita E. Habits make smartphone use more pervasive. Pers Ubiquitous Comput (2012) 16:105–14. doi: 10.1007/s00779-011-0412-2

13. Billieux J. Problematic use of the mobile phone: A literature review and a pathways model. Curr Psychiatry Rev (2012) 8:299–307. doi: 10.2174/157340012803520522

14. Lin YH, Chiang CL, Lin PH, Chang LR, Ko CH, Lee YH, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for Smartphone addiction. PloS One; (2016) 11(11):e163010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163010

15. Lee YS, Kim E-Y, Kim LS, Choi Y. Development and effect evaluation of smartphone addiction prevention program for adolescent (in Korean). Korean J Youth Counsel (2014) 22(1):303–34. doi: 10.35151/kyci.2014.22.1.013

16. İNal EE, Demİrcİ K, Çetİntürk A, Akgönül M, Savaş S. Effects of smartphone overuse on hand function, pinch strength, and the median nerve. Muscle Nerve (2015) 52(2):183–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.24695

17. Kim SH, Kim KU, Kim JS. Changes in cervical angle according to the duration of computer use. J Korean Soc Phys Med (2013) 7:179–87. doi: 10.21184/jkeia.2013.06.7.2.179

18. Sahin S, Ozdemir K, Unsal A, Temiz N. Evaluation of mobile phone addiction level and sleep quality in university students. Pak J Med Sci (2013) 29:913–8. doi: 10.12669/pjms.294.3686

19. Subba SH, Mandelia C, Pathak V, Reddy D, Goel A, Tayal A, et al. Ringxiety and the mobile phone usage pattern among the students of a medical college in South India. J Clin Diagn Res (2013) 7:205–9. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/4652.2729

20. Demirci K, Akgönül M, Akpinar A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J Behav Addict (2015) 4(2):85–92. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.010

21. Scimeca G, Bruno A, Gava L, Pandolfo G, Muscatello M, Zoccali R. The relationship between alexithymia, anxiety, depression, and internet addiction severity in a sample of Italian high school students. Sci World J (2014) 2014:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2014/504376

22. Montag C, Błaszkiewicz K, Sariyska R, Lachmann B, Andone I, Trendafilov B, et al. Smartphone usage in the 21st century: who is active on WhatsApp? BMC Res Notes. (2015) 4;8:331. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1280-z

23. Mei S, Xu G, Gao T, Ren H, Li J. The relationship between college students’ alexithymia and mobile phone addiction: Testing mediation and moderation effects. BMC Psychiatry (2018) 18(1):329. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1891-8

24. Gao T, Li J, Zhang H, Gao J, Kong Y, Hu Y, et al. The influence of alexithymia on mobile phone addiction: The role of depression, anxiety and stress. J Affect Disord (2018) 1(225):761–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.020

25. Hao Z, Jin L, Li Y, Akram H, Saeed M, Ma J, et al. Alexithymia and mobile phone addiction in Chinese undergraduate students: The roles of mobile phone use patterns. Comput Hum Behav (2019) 97:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.001

26. Çağan Ö., Ünsal ,A, Çelik N. Evaluation of college students’ the level of addiction to cellular phone and investigation on the relationship between the addiction and level of depression. Proc Soc Behav Sci (2014) 114:831–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.793

27. Baysan-Arslan S, Cebeci S, Kaya M, Canbal M. Relationship between internet addiction and alexithymia among university students. Clin Invest Med (2016) 39(6):111. doi: 10.25011/cim.v39i6.27513

28. Bagby R, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The Twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: I. Item selection and crossvalidation of the factor structure. The Twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: II. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. J Psychosom Res (1994) 38(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90006-X

29. Kafafi A, Aldawash F. The 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale (Arabic version). Cairo: Anglo-Egyptian Library (2011).

30. Säkkinen P, Kaltiala-Heino R, Ranta K, Haataja R, Joukamaa M. Psychometric properties of the 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale and prevalence of alexithymia in a Finnish adolescent population. Psychosomatics (2007) 48(2):154–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.2.154

31. Kwon M, Lee JY, Won WY, Park JW, Min JA, Hahn C, et al. Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS). PloS One (2013) 8(2):e56936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056936

32. Kwon M, Kim D-J, Cho H, Yang S. The Smartphone Addiction Scale: Development and Validation of a Short Version for Adolescents. PloS One (2013) 8:e83558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083558

33. Lopez-Fernandez O. Short version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale adapted to Spanish and French: Towards a cross-cultural research in problematic mobile phone use. Addict Behav (2017) 64:275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.013

34. Noyan C, Darcin A, Nurmedov S, Yilmaz O, Dilbaz N. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version among university students. Anatolian J Psychiatry (2015) 16:73. doi: 10.5455/apd.176101

35. Sfendla A, Laita M, Nejjar B, Souirti Z, Touhami AAO, Senhaji M. Reliability of the Arabic Smartphone Addiction Scale and Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version in Two Different Moroccan Samples. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw (2018) 21(5):325–32. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0411

36. Sifneos PE, Apfel-Savitz R, Frankel FH. The phenomenon of ‘alexithymia’: observations in neurotic and psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosomat (1977) 28:47–57. doi: 10.1159/000287043

37. Hamaideh SH. Alexithymia among Jordanian university students: Its prevalence and correlates with depression, anxiety, stress, and demographics. Perspect Psychiatr Care (2018) 54(2):274–80. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12234

38. Mason O, Tyson M, Jones C, Spotts S. Alexithymia: Its prevalence and correlates in British undergraduate sample. Psychol Psychother (2005) 78:113–25. doi: 10.1348/147608304X21374

39. Sayed MA. Arabic psychiatry and psychology: The physician who is philosopher and the physician who is not a philosopher: Some cultural considerations. Soc Behav Pers Int J (2002) 30:235–42. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2002.30.3.235

40. Alqahtani MM, Salmon P. Prevalence of somatization and minor psychiatric morbidity in primary healthcare in Saudi Arabia: A preliminary study in Asir region. J Fam Commun Med (2008) 15:27–33.

41. Leung L. Leisure boredom, sensation seeking, self-esteem, addiction: Symptoms and patterns of cell phone use. In Kojin EA, Utz S, Tanis M, Barnes SB. editors. Mediated interpersonal communication. New York, NY: Routledge (2008), p. 359–81.

42. Smetaniuk P. A preliminary investigation into the prevalence and prediction of problematic cell phone use. J Behav Addict (2014) 3:41–53. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.004

43. Martinotti G, Villella C, Di Thiene D, Di Nicola M, Bria P, Conte G, et al. Problematic mobile phone use in adolescence: a cross sectional study. J Public Health (2011) 19:545–51. doi: 10.1007/s10389-011-0422-6

44. Toda M, Monden K, Kubo K, Morimoto K. Mobile phone dependence and health-related lifestyle of university students. Soc Behav Pers (2006) 34(10):1277–84. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2006.34.10.1277

45. Chen B, Liu F, Ding S, Ying X, Wang L, Wen Y. Gender differences in factors associated with smartphone addiction: a cross-sectional study among medical college students. BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17(1):341. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1503-z

46. De-Sola Gutiérrez J, Rodríguez De Fonseca F, Rubio G. Cell-phone addiction: a review. Front Psychiatry (2016) 7:175. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175

47. Yang SY, Lin CY, Huang YC, Chang JH. Gender differences in the association of smartphone use with the vitality and mental health of adolescent students. J Am Coll Health (2018) 66(7):693–701. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1454930

48. Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JD. The alexithymia construct: A potential paradigm for psychosomatic medicine. Psychosomatics (1991) 32:153–64. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(91)72086-0

Keywords: alexithymia, smartphone addiction, university students, behavioral addiction, Smartphone Addiction Scale–Short Version (SAS-SV), Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS)

Citation: Elkholy H, Elhabiby M and Ibrahim I (2020) Rates of Alexithymia and Its Association With Smartphone Addiction Among a Sample of University Students in Egypt. Front. Psychiatry 11:304. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00304

Received: 12 December 2019; Accepted: 26 March 2020;

Published: 24 April 2020.

Edited by:

Domenico De Berardis, Azienda Usl Teramo, ItalyReviewed by:

Marco Di Nicola, Agostino Gemelli University Polyclinic, ItalyMirko Manchia, University of Cagliari, Italy

Copyright © 2020 Elkholy, Elhabiby and Ibrahim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hussien Elkholy, aC5lbGtob2x5QG1lZC5hc3UuZWR1LmVn

Hussien Elkholy

Hussien Elkholy Mahmoud Elhabiby

Mahmoud Elhabiby Islam Ibrahim

Islam Ibrahim