94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Psychiatry, 14 November 2019

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00794

This article is part of the Research TopicCompulsory Interventions in Psychiatry: an Overview on the Current Situation and Recommendations for Prevention and Adequate UseView all 38 articles

For psychiatric patients, compulsory admission and coercive measures can constitute distressing and sometimes traumatizing experiences. As a consequence, clinicians aim at minimizing such procedures. At the same time, they need to ensure high levels of safety for patients, staff and the public. In order to prevent compulsory measures and to favor the use of less restrictive alternatives, innovative interventions improving the management of dangerous situations are needed. Animal-assisted therapy (AAT) is being applied in a variety of diagnoses and treatment settings, and could have the potential to reduce aggression and psychopathology. Therefore, AAT might be of use in the prevention and early treatment of aggression, and might constitute a promising component of treatment alternatives to forced interventions. To our knowledge, no study evaluating the effect of AAT on compulsory measures in persons with psychiatric diseases has been published up to date. This narrative expert review including a systematic literature search examines the published literature about the use of AAT in psychiatry. Studies report reduced anxiety and aggressiveness as well as positive effects on general wellbeing, self-efficacy, quality of life and mindfulness. Although literature on the applicability of AAT as a component of preventive or de-escalating treatment settings is sparse, beneficial effects of AAT have been reported. Therefore, we encourage examining AAT as a promising new treatment approach to prevent compulsory measures.

Mental health care has to exert multiple functions: primarily, psychiatry has to offer treatment options to enable patients’ restitution of mental health and an optimal quality of life (1–3). However, in addition, psychiatry is also tasked with the role to protect the patients and others from dangerous situations caused by mental illness, and to provide care for patients that would normally agree with treatment, but are unable to do so due to their impaired judgment (4, 5). This makes it necessary to be able to resort to coercive measures like compulsory admission, safety measures (e.g., seclusion or fixation), and involuntary treatment, in specific situations (2, 3). For psychiatric patients, these measures can constitute distressing and sometimes traumatizing experiences (6). In addition, coercion can increase stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatric patients (7–9). As a consequence, clinicians aim at minimizing such procedures (10–13). In order to prevent compulsory measures and to favor the use of less restrictive alternatives, innovative interventions improving the management of dangerous situations are needed.

The main indication for the use of coercion in psychiatry is to avoid danger for the patient or others, which is caused by aggressive behavior against others (i.e., aggression, violence) or the patient (i.e., self-directed aggression, self-harm, suicide attempts) (3). These risk situations can occur due to acute or chronic aggressive patient behavior with a variety of different causes and triggers (1).

In order to prevent or reduce coercive treatment in psychiatry, innovative treatment approaches and interventions are needed. These interventions could, e.g., directly target at reducing the probability of risk behavior, thus reducing the need for coercive measures (7). On the other hand, they could also aim at improving illness-related factors promoting aggressive behavior (e.g., emotion regulation, coping with stressful situations, and anxiety) (14). In addition, measures for the prevention of risk situations and, therefore, coercion in psychiatry should have a positive benefit-risk-assessment.

Animal-assisted therapy (AAT) has gained increasing interest in clinical psychiatry and could have the potential to prevent or reduce impending risk behavior and coercion (15). Currently, AAT is more and more employed in psychosocial facilities. It is being assumed that peaceful contact between humans and animals has positive effects on the wellbeing of persons with a wide variety of diseases (16). For example, there have been positive effects for people with somatic, intellectual, and mental disabilities, children with developmental problems, geriatric patients, or persons after surgery (15–19).

Cirulli et al. (16) conducted a review of the existing literature on psychiatric patients and concluded that in order to understand the underlying mechanisms that play a role in animal-human interactions, further research would be needed. Also, they pointed out the need for more standardized AAT treatment protocols. The reviewed studies indicated that animals absorb human attention in an innocent, non-threatening manner that allows persons to calm down.

A systematic review on randomized controlled trials by Kamioka et al. (20) identified 11 studies. Their quality according to Cochrane criteria was too low to perform a meta-analysis. The authors resumed that AAT could be an effective intervention in persons with psychological and behavioral difficulties. For example, persons with depression, schizophrenia, or substance use disorders could benefit from AAT—with the premise that they have a positive relation to animals.

A recent review of randomized controlled trials on AAT was performed by Maujean et al. (17). These authors also criticized the deficient quality of the studies. Eight publications could be included. Identified methodological weaknesses were—among others—a missing control group, differences in outcome variables, and missing assessment of the specificity of positive effects during AAT. It therefore remained unclear whether the positive effects might have been merely caused by the higher attention given to the patients due to the intervention instead of the intervention itself. There have been no reports of negative effects due to AAT.

The only meta-analysis on AAT was conducted by Nimer and Lundahl (21). The authors included every type of AAT and did not use any restrictions regarding the examined patient population, which lead to the inclusion of 49 studies. The authors found moderate positive associations of AAT with improvement of autism symptoms, medical difficulties in general, behavioral problems, and emotional wellbeing.

O’Haire et al. (22) systematically reviewed literature on AAT for trauma, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They examined six studies with participants who were survivors of childhood abuse and military veterans and found reduced depressive and PTSD symptoms, and reduced anxiety. Because of a low level of methodological rigor in most studies, the authors indicate the preliminary nature of this area of investigation.

AAT is most commonly used in pediatric care and in nursing homes. It helps to decrease children’s pain, especially in pediatric palliative care (23) and is applied according to a manual, the “Therapy Animals Supporting Kids” (TASK) Program (24). In nursing homes, AAT seems to increase mental and physical activity in elderly persons. Due to these positive effects, in Switzerland, approximately 80% of the nursing homes integrate animals into their daily routines. Some uncounted number of nursing homes even allow the residents to take their personal pets into the homes, even though major hygienic challenges result.

Around 60% of psychiatric clinics house animals on their premises (18) and it has been shown that the presence of cats positively influences patient satisfaction in psychiatric wards (18).

The dog as the prototype of a companion animal (25) is the most commonly used animal in AAT (26). Researchers have suggested that dogs would reduce stress and fear in human beings. Studies including healthy participants reported positive effects of the presence of a dog on cortisol level, blood pressure, and pulse frequency (25).

In summary, aggression against others and self-directed aggression are frequent causes for compulsory measures and involuntary treatment in current psychiatric clinical practice. AAT could be an innovative approach to reduce aggression in different patient populations, but up to now, no publication has specifically examined this issue. Furthermore, there are—to the authors’ knowledge—currently no studies directly evaluating the effect of AAT on the frequency or use of coercive measures in psychiatry. Thus, the current mini-review aimed at examining the published literature on the use of AAT in psychiatry with a focus on applicability to reduce risk behavior and improve illness-related factors promoting aggressive behavior as proxies for the potential to reduce coercion in clinical psychiatry.

As AAT in psychiatry with the aim of reducing aggression and coercion has to be considered as an emerging field, meta-analyses currently would only be of limited use. We therefore conducted a narrative expert review with a systematic literature search.

Author SW searched the PubMed and PsycINFO online databases using a combination of search terms related to AAT, psychiatry, aggression, and coercion. There was no literature specifically focusing on coercion. Therefore we focused on domains (aggression, agitation, anxiety) associated with reduction of coercion. We applied no restriction on start date until June of 2019. Reference lists of included literature were screened for additional applicable publications. SW screened all studies according to the following inclusion criteria. We included longitudinal, cross-sectional, and case-control studies (journal articles, book chapters, and dissertations) reporting the effects of animal-assisted interventions on any psychiatric symptom. We included all studies with an age of cases/controls of at least 18 years of age. We applied no language restriction and required patients to have a professionally established psychiatric diagnosis according to DSM or ICD.

We performed qualitative analysis of all included publications. The main outcome variables were the symptom severities as reported in the individual studies. We extracted population details including diagnosis, the measured symptoms, and the type of AAT that was applied.

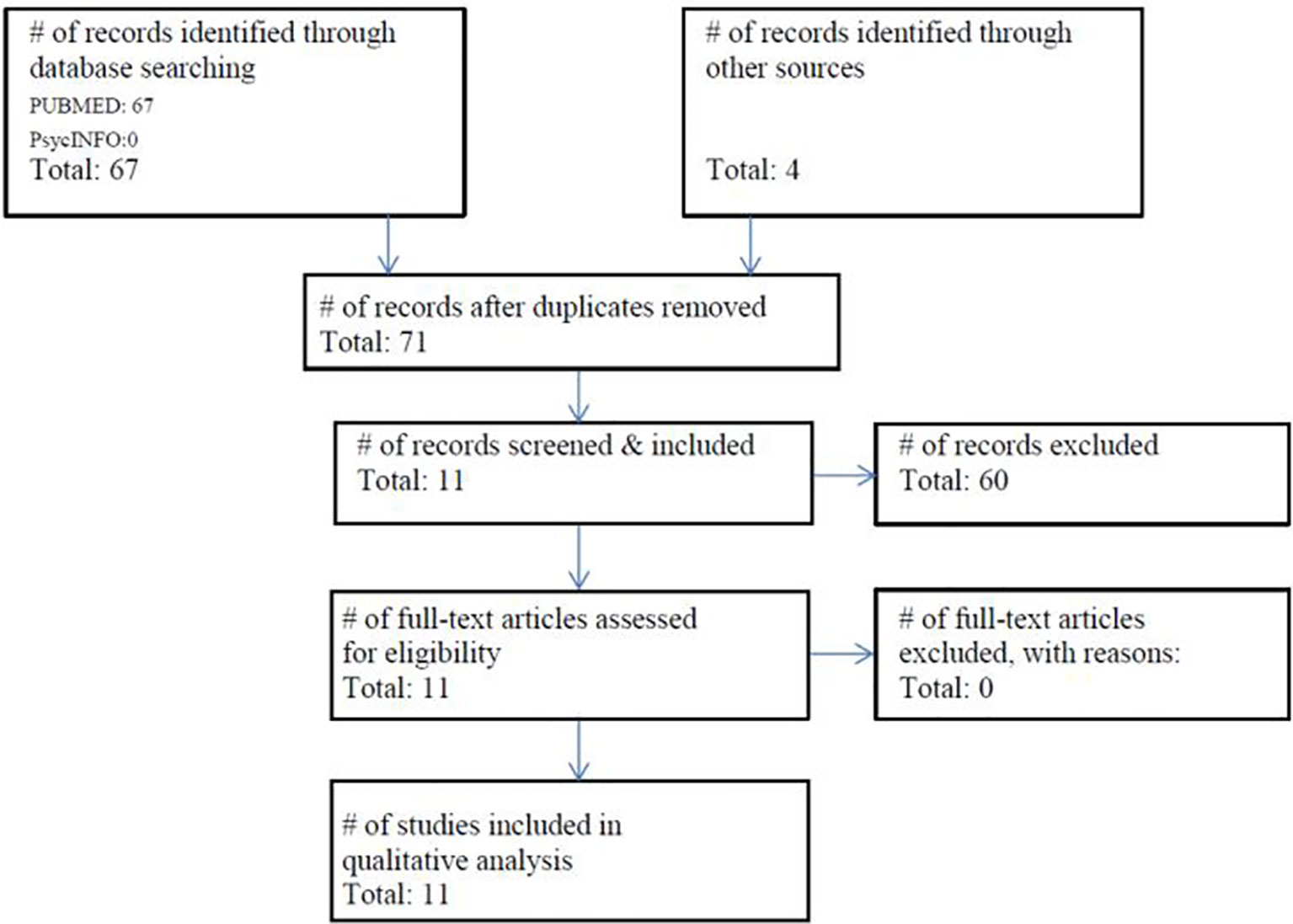

The literature search identified 71 possible studies of interest. After screening and applying in- and exclusion criteria, 60 studies were excluded. Using the preferred reporting items of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) template, we summarize the study selection procedure in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Flowchart of the literature search (21.06.2019) and included studies according to the PRISMA guidelines (27).

The final sample consisted of 11 studies; Table 1 gives an overview of them showing population details, measured symptoms, and type of AAT.

Nathans-Barel et al. (32) reported positive effects of a dog-assisted intervention compared to a psychosocial treatment in persons suffering from chronic schizophrenia. Furthermore, they reported a positive effect on their quality of life.

Schramm et al. (15) examined the effect of a sheep-assisted therapy in depressive patients within the framework of a mindfulness based approach. The intervention was practicable and led to reduced depressive symptoms and rumination, while the ability for mindfulness was increased.

Sockalingam et al. (35) report the case of a patient who, following an assault with a concurrent mood disorder, profited greatly from a dog-assisted intervention over a 3-week period.

Berget et al. (28) conducted 12 weeks of AAT in persons with schizophrenia, affective disorders and personality disorders. They found a significant improvement in self-efficacy and the ability to cope, but no difference in general quality of life.

Peluso et al. (36) examined AAT in patients with dementia and found positive influence on anxiety and aggressiveness. Nordgren and Engstrom (33) observed positive effects of a dog-assisted intervention on behavioral symptoms in dementia. Majic et al. (31) examined the influence of a dog-assisted therapy on agitation/aggression and depression in persons with dementia. They found constant frequency and severity of symptoms of agitation/aggression and depression in the group with AAT while the control group not receiving AAT displayed a significant increase of the symptoms.

Lang et al. (30) examined symptoms of anxiety before and after a dog-assisted therapeutic session in persons with acute psychotic symptoms. Also, they observed a significant reduction of anxiety and fear after the session. In depressive patients, Hoffmann et al. (28) observed that a single therapeutic session with a dog led to reduced fear as opposed to a session without a dog. Furthermore, Barker and Dawson (26) compared the effects of an AAT session with those of a regularly scheduled therapeutic recreation session using a pre- and posttreatment crossover study design in 230 patients. They found reductions in anxiety scores after the AAT session for patients with psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and other disorders, and after the therapeutic recreation session for patients with mood disorders. However, there were no significant differences in reduction of anxiety between the two types of sessions (26).

Nurenberg et al. (34) examined the effect of horse- or dog-assisted therapy in chronically ill psychiatric patients with a history of violent behavior (at least three committed violent acts in the last 12 months). They observed that both AAT interventions reduced aggressiveness in these patients.

In addition to the expected benefits of AAT, close contact of animals and humans always bears risks, such as allergies, infections, and animal-related accidents (37). A systematic review by Bert et al. (37) including 36 studies on children, psychiatric, and elderly patients shows that the benefits of AAT greatly outweigh its risks. Furthermore, the authors suggest that the implementation of simple hygiene protocols is sufficient to minimize the risk of infections.

The question whether AAT could help to prevent aggression and coercion in psychiatry has not been specifically addressed in a review thus far. A number of studies have examined the effects of AAT in psychiatric patient samples, and some authors have tried to summarize the results of these studies with different research objectives in systematic and non-systematic reviews. We found studies reporting positive effects of AAT on quality of life, mindfulness, depression, rumination, self-efficacy, dementia, anxiety, and aggression. The results are in line with the previous studies stating the various positive effects of AAT in different mental health settings. Still, qualitative and quantitative syntheses are complicated due to small sample sizes and methodological limitations of the published studies. In particular, there is limited evidence for the specificity of many positive findings in AAT, necessitating future research with more advanced study protocols.

However, in the current narrative expert review including a systematic literature search, we found non-systematic indications of a positive effect of AAT on different psychiatric conditions connected with risk behavior and coercion, in particular with anxiety and aggression. Furthermore, there is a broad consensus that the benefits of AAT greatly outweigh its risks.

We examined AAT from a new perspective taking into account its potential implications for the reduction of coercive treatment. Due to this strong clinical implication, we consider it a highly relevant topic. Furthermore, our literature search is up to date and systematic.

Multiple factors constitute methodological limitations of this review. Due to the current state of the literature, a narrative expert review was conducted, and some publications on the subject could have been overlooked. Also, the literature search, selection process, and data extraction have been conducted by one single author. Furthermore, no systematic quality assessment of the included publications was performed, and an analysis of publication bias and quantitative synthesis of the findings were not possible. However, this approach is adequate considering the current state of the field. Further limitations of this study are that, although we found indications that AAT may help to reduce coercive measures in psychiatry, we did not elaborate a concept on how to implicate AAT in acute psychiatric settings. Also, we found no study examining directly the influence of AAT on coercion in psychiatry. Future research may show if the current non-systematic evidence for a potential use of AAT can be replicated and corroborated.

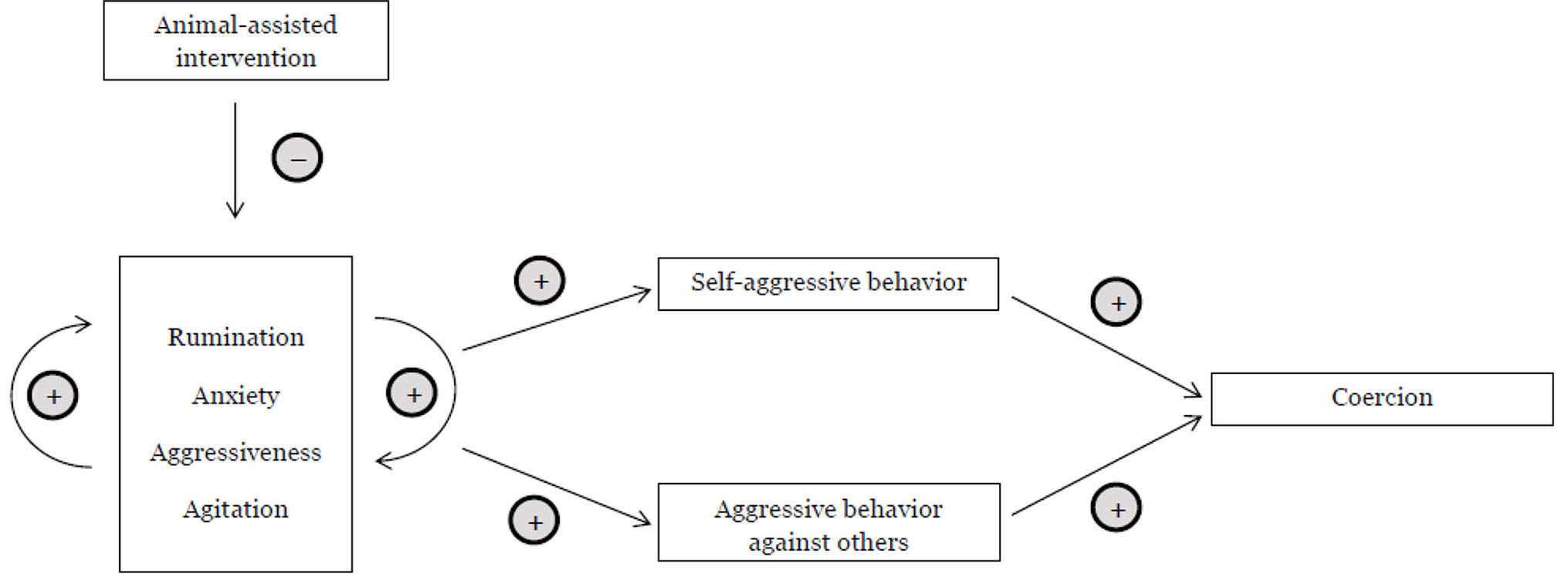

AAT greatly benefits human health—it enhances our general wellbeing as well as it enables persons with psychiatric diseases to achieve better therapeutic outcomes in many different areas and for a variety of symptoms. In the context of coercive treatment in psychiatry, we highlight the promising potential of AAT to relieve symptoms leading to aggressive behavior. We hypothesize that applying AAT in psychiatric wards reduces the need for coercive treatment. Furthermore, we think that even at later stages in the escalation process leading to a coercive measure, AAT could deescalate the situation so far as to render the coercion unnecessary. It has been shown that aggressiveness itself diminishes in the presence of a therapeutic animal. Figure 2 shows the process in which AAT could deescalate and prevent coercive measures.

Figure 2 Deescalative Potential of AAT. This figure shows potential connections between psychiatric sypmtom domains, aggressive behavior, and coercion. –: Increase (decrease) in the previous domain leads to a decrease (increase) in the following domain. +: Increase (decrease) in the previous domain leads to an increase (decrease) in the following domain.

We suggest implementing AAT as a low-threshold therapeutic measure in psychiatric wards as a social psychiatric mean to minimize coercion. We hypothesize that the presence of an animal at, for example, the department for persons suffering from schizophrenia would lead to a decline of agitation in the patients of the ward—this could improve the general atmosphere of a ward. Furthermore, we hypothesize that, if a certain therapy animal is known to the patients, this animal could calm persons even in high-risk situations and subsequently enable mutual agreement between the patient and the therapist, which in turn would allow for a better relationship between patient and animal and lead to an enhanced treatment compliance with less and less coercive treatment necessary.

Based on our findings, we suggest integrating AAT into an aggression-reducing setting, potentially combining it with an enriched environment, music therapy, and other supportive therapies in addition to established psychotherapy and psychopharmacotherapy. AAT could thus be implemented as one of multiple non-pharmacological treatment approaches. Systematic studies, however, are needed to confirm the hypothesis that AAT can help to prevent coercive treatment.

SW and CH designed the study and wrote the initial draft of the paper. SB and UL revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have contributed to, read, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of this work by the Research Fund of the Psychiatric University Hospital Basel, 2nd call, 2015. Also, we sincerely acknowledge the helpful debates and support of our dear colleagues Dr. phil. Ulrike Heitz and Dr. phil. Lisa Hochstrasser.

1. Deutschenbaur L, Lambert M, Walter M, Naber D, Huber CG. Long-term treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: focus on pharmacotherapy. Nervenarzt (2014) 85(3):363–75. quiz 376-367. doi: 10.1007/s00115-013-3807-7

2. Fröhlich D, Schweinfurth N, Lang UE, Huber CG. Zwangsmassnahmen in der Psychiatrie. Leading Opin Neurol Psychiatr (2017) 3:30–2.

3. Kowalinski E, Schneeberger AR, Lang UE, Huber CG. Safety through locked doors in psychiatry?. In: Jakov G, Henking T, Nossek A, Vollmann J, editors. Beneficial coercion in psychiatry?., vol. 147-162 Münster: mentis (2017).

4. Huber CG, Schneeberger AR, Kowalinski E, Frohlich D, von Felten S, Walter M, et al. Suicide risk and absconding in psychiatric hospitals with and without open door policies: a 15 year, observational study. Lancet Psychiatry (2016) 3(9):842–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30168-7

5. Schneeberger AR, Kowalinski E, Frohlich D, Schroder K, von Felten S, Zinkler M, et al. Aggression and violence in psychiatric hospitals with and without open door policies: A 15-year naturalistic observational study. J Psychiatr Res (2017) 95:189–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.017

6. Schneeberger AR, Huber CG, Lang UE. Open wards in psychiatric clinics and compulsory psychiatric admissions. JAMA Psychiatry (2016) 73(12):1293. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1738

7. Huber CG, Sowislo JF, Schneeberger AR, Flury Bodenmann B, Lang UE. Empowerment - ein Weg zur Entstigmatisierung der psychisch Kranken und der Psychiatrie. Schweiz Arch Neurol Psychiatr (2015) 166:225–31.

8. Sowislo JF, Gonet-Wirz F, Borgwardt S, Lang UE, Huber CG. Perceived dangerousness as related to psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric service use - a vignette based representative population survey. Sci Rep (2017a) 8:45716. doi: 10.1038/srep45716

9. Sowislo JF, Lange C, Euler S, Hachtel H, Walter M, Borgwardt S, et al. Stigmatization of psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric service use: a vignette-based representative population survey. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2017b) 267(4):351–7. doi: 10.1007/s00406-016-0729-y

10. Jungfer HA, Schneeberger AR, Borgwardt S, Walter M, Vogel M, Gairing SK, et al. Reduction of seclusion on a hospital-wide level: successful implementation of a less restrictive policy. J Psychiatr Res (2014) 54:94–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.020

11. Lang UE, Borgwardt S, Walter M, Huber CG. Einführung einer “Offenen Tür Politik” - Was bedeutet diese konkret und wie wirkt sie sich auf Zwangsmaßnahmen aus? Recht & Psychiatrie (2017) 35:72–9.

12. Hochstrasser L, Frohlich D, Schneeberger AR, Borgwardt S, Lang UE, Stieglitz RD, et al. Long-term reduction of seclusion and forced medication on a hospital-wide level: Implementation of an open-door policy over 6 years. Eur Psychiatry (2018a) 48:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.09.008

13. Hochstrasser L, Voulgaris A, Moller J, Zimmermann T, Steinauer R, Borgwardt S, et al. Reduced frequency of cases with seclusion is associated with “Opening the Doors” of a psychiatric intensive care unit. Front Psychiatry (2018b) 9:57. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00057

14. Stepanow C, Huber CG. Einschätzung und Vorhersage von Aggression. NeuroTransmitter (2014) 25(12):42–6.

15. Schramm E, Hediger K, Lang UE. From animal behavior to human health: an animal-assisted mindfulness intervention for recurrent depression. Z Psychol (2015) 223(3):192. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000220

16. Cirulli F, Borgi M, Berry A, Francia N, Alleva E. Animal-assisted interventions as innovative tools for mental health. Ann Ist Super Sanita (2011) 47(4):341–8. doi: 10.4415/ann_11_04_04

17. Maujean A, Pepping CA, Kendall E. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of animal-assisted therapy on psychosocial outcomes. Anthrozoös: Multidiscip J Interact People Anim (2015) 28(1):23–36. doi: 10.2752/089279315X14129350721812

18. Templin JC, Hediger K, Wagner C, Lang UE. Relationship between patient satisfaction and the presence of cats in psychiatric wards. J Altern Complement Med (2018) 24(12):1219–20. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0263

19. Hediger K, Thommen S, Wagner C, Gaab J, Hund-Georgiadis M. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on social behaviour in patients with acquired brain injury: a randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):5831. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42280-0

20. Kamioka H, Okada S, Tsutani K, Park H, Okuizumi H, Handa S, et al. Effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med (2014) 22(2):371–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.016

21. Nimer J, Lundahl B. Animal-assisted therapy: a meta-analysis. Anthrozoös: Multidiscip J Interact People Anim (2007) 20:225–38. doi: 10.2752/089279307X224773

22. O’Haire ME, Guerin NA, Kirkham AC. Animal-Assisted Intervention for trauma: a systematic literature review. Front Psychol (2015) 6:1121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01121

23. Gilmer MJ, Baudino MN, Tielsch Goddard A, Vickers DC, Akard TF. Animal-assisted therapy in pediatric palliative care. Nurs Clin North Am (2016) 51(3):381–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2016.05.007

24. Phillips A, McQuarrie D, (2016). Therapy Animals Supporting Kids (TASK)™ Program [Online]. American Humane. Available: https://www.americanhumane.org/app/uploads/2016/08/therapy-animals-supporting-kids.pdf [Accessed 2019].

25. Odendaal JS. Animal-assisted therapy - magic or medicine? J Psychosom Res (2000) 49(4):275–80. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00183-5

26. Barker SB, Dawson KS. The effects of animal-assisted therapy on anxiety ratings of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv (1998) 49(6):797–801. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.6.797

27. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Int Med (2009) 151(4):264–9.

28. Berget B, Ekeberg O, Braastad BO. Animal-assisted therapy with farm animals for persons with psychiatric disorders: effects on self-efficacy, coping ability and quality of life, a randomized controlled trial. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health (2008) 4:9. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-4-9

29. Hoffmann AO, Lee AH, Wertenauer F, Ricken R, Jansen JJ, Gallinat J, Lang UE. Dog-assisted intervention significantly reduces anxiety in hospitalized patients with major depression. Eur J Integr Med (2009) 1(3):145–48. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2009.08.002

30. Lang UE, Jansen JB, Wertenauer F, Gallinat J, Rapp MA. Reduced anxiety during dog assisted interviews in acute schizophrenic patients. Eur J Integr Med (2010) 2:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2010.07.002

31. Majic T, Gutzmann H, Heinz A, Lang UE, Rapp MA. Animal-assisted therapy and agitation and depression in nursing home residents with dementia: a matched case-control trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2013) 21(11):1052–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.03.004

32. Nathans-Barel I, Feldman P, Berger B, Modai I, Silver H. Animal-assisted therapy ameliorates anhedonia in schizophrenia patients. Controlled Pilot Study Psychother Psychosom (2005) 74(1):31–5. doi: 10.1159/000082024

33. Nordgren L, Engstrom G. Effects of dog-assisted intervention on behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Nurs Older People (2014) 26(3):31–8. doi: 10.7748/nop2014.03.26.3.31.e517

34. Nurenberg JR, Schleifer SJ, Shaffer TM, Yellin M, Desai PJ, Amin R, et al. Animal-assisted therapy with chronic psychiatric inpatients: equine-assisted psychotherapy and aggressive behavior. Psychiatr Serv (2015) 66(1):80–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300524

35. Sockalingam S, Li M, Krishnadev U, Hanson K, Balaban K, Pacione LR, et al. Use of animal-assisted therapy in the rehabilitation of an assault victim with a concurrent mood disorder. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2008) 29(1):73–84. doi: 10.1080/01612840701748847

36. Peluso S, De Rosa A, De Lucia N, Antenora A, Illario M, Esposito M, et al. Animal-assisted therapy in elderly patients: evidence and controversies in dementia and psychiatric disorders and future perspectives in other neurological diseases. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol (2018) 31(3):149–57. doi: 10.1177/0891988718774634

Keywords: compulsory treatment, animal-assisted therapy, psychiatry, aggression, prevention

Citation: Widmayer S, Borgwardt S, Lang UE and Huber CG (2019) Could Animal-Assisted Therapy Help to Reduce Coercive Treatment in Psychiatry? Front. Psychiatry 10:794. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00794

Received: 10 April 2019; Accepted: 04 October 2019;

Published: 14 November 2019.

Edited by:

Matthias Jaeger, Psychiatrie Baselland, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Michaela Pascoe, Victoria University, AustraliaCopyright © 2019 Widmayer, Borgwardt, Lang and Huber. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sonja Widmayer, c29uamEud2lkbWF5ZXJAdW5pYmFzLmNo

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.