- Department of Neurology, The First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Background: Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder characterized by rapidly progressive dementia. Growing evidence suggests that antidepressant usage was associated with dementia. Given the commonality of depression in CJD, it is necessary to investigate the effect of antidepressants on CJD.

Methods: First, we report a case of sporadic CJD (sCJD) with depression where the condition worsened rapidly after using a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressant. Second, a systematic literature survey was conducted to investigate the effect of antidepressants on the survival time of sCJD patients with depression. Thirteen cases plus our case were included for qualitative analysis. Twelve subjects were included in the Kaplan–Meier survival and Cox regression analysis. Finally, we provide a postulation of pathophysiological mechanism in CJD.

Results: The median survival time of all patients was 6.0 months, of which patients with SNRIs were significantly shorter than those with first-generation antidepressants (2.0 vs. 6.0 months; log rank, P = .008) and relatively shorter than those with nonselective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; 4.0 vs. 6.0 months; log rank, P = .090). In comparison with first-generation antidepressants, the use of SNRIs [hazard ratio (HR), 23.028; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.401 to 378.461; P = .028] remained independently associated with shorter survival time.

Conclusions: The use of antidepressants, especially SNRIs, was associated with a shorter survival time of sCJD patients. The possible changes in neurotransmitters should be emphasized. Scientifically, this study may provide insights into the mechanism of CJD. Clinically, it may contribute to the early diagnosis of CJD.

Introduction

Depression is common in the elderly. Its prevalence rate is as high as 11.19%, and this increases progressively with worsening cognitive impairment (1). The presence of depression is an acknowledged risk factor for dementia (2); it can even double the risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (3, 4). Many reasons lie behind the prescription of antidepressant drugs, which increased dramatically from 1999 to 2014 (5). However, some studies have questioned whether antidepressants confer any benefits in terms of cognitive decline (6–9). Recently, a meta-analysis indicated that antidepressant usage was associated with AD/dementia (10). Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) may be associated with a reduced risk (11) or no risk of dementia (12) for depressed patients, whereas nonselective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) antidepressant drugs, including monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, and serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been reported to possess an intermediate risk (11–13).

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), a fatal neurodegenerative disorder characterized by rapidly progressive dementia, is divided into the sporadic (sCJD), familial (fCJD), variant (vCJD), and iatrogenic (iCJD) subtypes (14). sCJD accounts for the majority, i.e., 85% of all CJD cases, with an annual worldwide incidence of one to two cases/million population (15). Although rare, the overall mortality rate of sCJD has been increasing since 1993 (16). There is no effective treatment for CJD, so it is important to identify modifiable risk factors for CJD and to delay disease progression. Psychiatric manifestations are often the first symptoms to appear in vCJD. Recent studies have shown that they are also more prevalent in sCJD than previously thought. Most commonly, these are exhibited as depression in 16%–37% of cases (17–19). While treatment of the psychiatric symptoms with hypnotics, anxiolytics, or antipsychotic drugs may offer relief to CJD patients, it appears that antidepressant drugs are ineffective (19). As is the case in some other dementias, the implication is that antidepressants may also fail to benefit CJD patients.

Here, we report a case of sCJD in which depression was the first symptom, and the condition worsened rapidly after the administration of an SNRI antidepressant. Subsequently, a systematic review of the literature was undertaken to explore the characteristics of sCJD patients with depressive symptoms as well as the effect of treatment with antidepressants on sCJD. This report aims to provide novel insights into the underlying causes and treatment of CJD and dementia.

Case Report

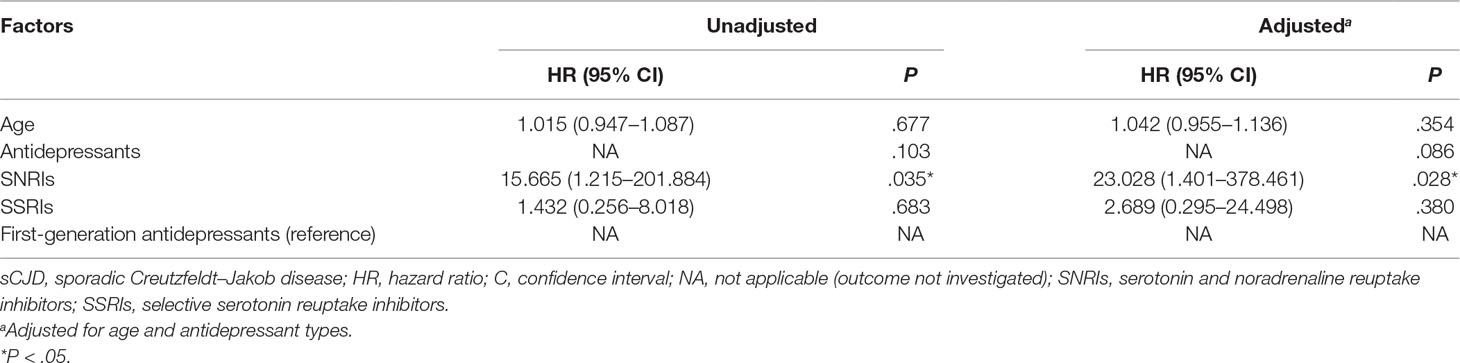

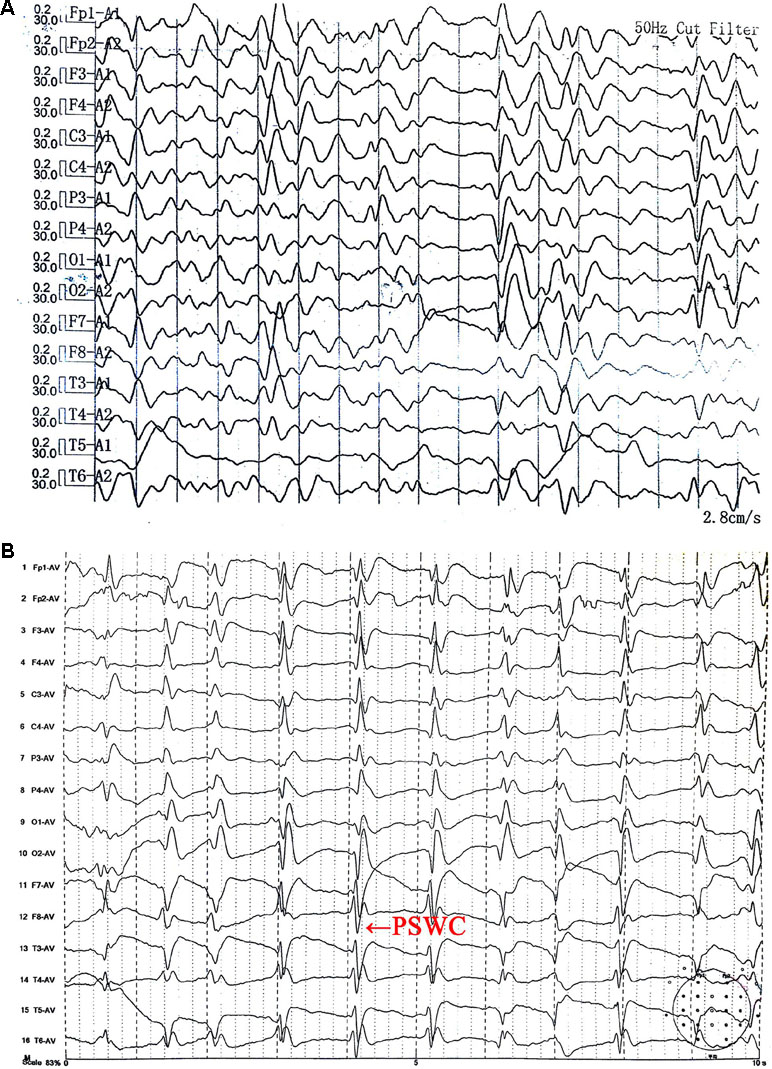

Ms. S was a 63-year-old female with no previous medical or psychiatric history. In July 2017, she presented with dizziness, weakness, chronic shoulder pain, and high blood pressure. She informed her family that she felt helpless and sick. The preliminary examination revealed nothing but multiple lacunar infarcts in brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. On September 17, 2017, she exhibited anhedonia, fear, anxiety, impatience, and a propensity to cry after being annoyed with others. She was examined in the psychiatric unit of the local hospital. Her value on the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) was 53.75, which pointed to mild depression, whereas on the Hastgawa Dementia Scale (HDS), she scored 13.0, which suggested probable dementia (education: primary school). The memory quotient (MQ) of Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS) was 59. Her sleep was normal. She was diagnosed with depression, and sertraline 50 mg/day was prescribed. Her symptoms nonetheless worsened with insomnia, garrulity, irritability, and gait imbalance. Her memory function deteriorated, and she became disoriented. The psychiatrist changed the antidepressant drug to venlafaxine 75 mg/day on October 8, 2017. However, instead of improving, the condition rapidly worsened. Her speech became hypophonic and monotonous with a paucity of content. She was sleepy during the day and sometimes burst into tears. Her arms curled up, indicating panic. She developed psychomotor retardation, responded poorly to questions, experienced visual hallucination, and suffered from a rigid posture with paroxysmal myoclonus and an inability to walk. The changes in her symptoms were initially considered to be side effects of venlafaxine. Two weeks later, she had deteriorated further and was unable to talk, exhibiting dysphagia and suffering from urinary incontinence. The symptoms did not improve after the withdrawal of the antidepressant. An assessment of her electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed generalized slow activity (Figure 1A). She was then transferred to the neurologic ward of our hospital where the following neurological findings were detected: akinetic mutism (AM), normal muscle strength, increased muscle tension, brisk tendon reflexes, and unresponsive pathologic reflexes. We performed a hematology screen for endocrine, metabolic, autoimmune, neoplastic, and infectious diseases, which were all negative. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies, including a paraneoplastic, an autoimmune antibody panel, and a tubercular, fungal antibody survey were also negative. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) of the brain MRI showed hyperintensities in the bilateral frontal lobe, corona radiate, and near the anterior and posterior horns of the lateral ventricle (Figure 2A). Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) showed hyperintensities in the bilateral caudate nucleus and putamen (Figure 2B). A diagnosis of CJD was considered. One week after admission, the second EEG was performed, revealing partially periodic sharp wave complexes (PSWC; Figure 1B). No gene mutations associated with genetic CJD were found, but methionine homozygotes were detected at codon 129 of the prion protein gene. The final diagnosis was probable sCJD according to the diagnostic criteria for sCJD (20, 21). Antibiotics, antiviral, and corticosteroid therapies had been tried since admission, but none of them worked. Ultimately, she was discharged from the hospital.

Figure 1 Electroencephalogram (EEG) (A) on October 26, 2017 showed generalized slow activity. The second EEG (B) on November 2, 2017 showed partially periodic sharp wave complexes (PSWC).

Figure 2 Brain magnetic resonance imaging magnetic. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (A) showed hyperintensities in the bilateral frontal lobe, corona radiate, and near the anterior and posterior horns of the lateral ventricle. Diffusion-weighted imaging (B) showed hyperintensities in the bilateral caudate nucleus and putamen on November 1, 2017.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and PsycINFO up to May 2018 for previous cases using the key words “Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease AND depression.” The reports were restricted to those published and unpublished in English and those including human subjects. The inclusion criteria were as follows: case reports, case series, previous literature reviews, or systematic reviews describing sCJD patients with depression as the first symptom and receiving the treatment for depression. The CJD patients had to meet the WHO or 2009 Consortium diagnostic criteria for definite or probable sCJD (20, 21). To minimize confounders, such as the effect of other medications on outcomes, the included cases were those in which depression was the only symptom diagnosed initially. Two authors independently decided on the selection.

Data Extraction

The data extracted included study name, study characteristics, patient characteristics, and the duration, institutional care, symptoms, examinations, treatments, and diagnosis of distinct phases. The duration of CJD patients was divided into three phases based on the main symptoms. The first phase was the prodromal phase, with mental manifestations; the second phase was the intermediate phase, with progressive dementia, myoclonus, psychiatric disorder, pyramidal signs, and extrapyramidal performance; the third phase was the late phase, with incontinence, AM, coma, or decorticate rigidity. If an article did not distinguish between the duration of the second and third phases, we utilized a value of half of the total duration of the two periods as their respective durations. Data were graded by two authors independently according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence (22).

Statistical Analysis

A systematic analysis was performed. Categorical variables were described using proportions and continuous variables using medians and interquartile range (IQR). A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was conducted in those patients for whom we had data on the three-phase duration and the use of antidepressants. Antidepressants were categorized into three classes, SSRIs, newer non-SSRI antidepressants (mostly SNRIs), and first-generation antidepressants (mostly TCA) according to the Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical (ATC) classification system (World Health Organization, 1999). The log rank test was used to compare the survival distributions of different groups. Finally, a multivariate Cox regression analysis with Enter was undertaken to determine the predictors of survival. Due to the small number of cases, we considered only three factors: gender, age, and antidepressant type. The model with a significant score test and a smaller deviance in likelihood ratio test will be preferred. Significance was set at P < .05 (two-sided test). Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS v17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study Identification and Characteristics

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed (23). The PRISMA flow diagram is depicted in eFigure in the Supplementary Material. In our literature search, we identified 13 cases from 12 articles that met our inclusion criteria for qualitative analysis (24–35). Subsequently, 11 cases from 10 articles were included for qualitative analysis (24–26, 28, 30–35). With the addition of our case, a total of 12 subjects could be included in the Kaplan–Meier survival and multivariate Cox regression analysis.

The characteristics and evidence levels of the 14 cases published from 1993 to 2017 are shown in eTable in the Supplementary Material. All included articles were case reports. The age of all subjects was 58.8 (55.5–61.5) years with 11 (79%) being female. After administration of antidepressants, only 1 case out of 13 (8%) showed improved depressive symptoms.

Survival Time of Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Patients with Different Antidepressants

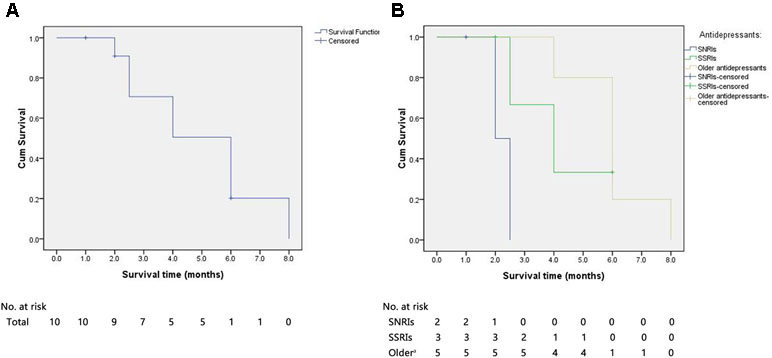

A Kaplan–Meier survival curve for all of the sCJD patients who had used antidepressants is shown in Figure 3. The median survival time of all of the cases was 6.0 months. The cumulative incidences with survival times less than 3, 6, and 12 months were 30.0%, 90.0%, and 100%, respectively. All of the patients died within 1 year after onset.

Figure 3 The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for sCJD patients with antidepressants. (A) Survival time for all patients. (B) Survival time for patients stratified according to the type of antidepressant. X-axis represents survival time (months) and Y-axis represents survival probability. sCJD = sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease; SNRIs = serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. aReferred to first-generation antidepressants.

The use of antidepressants in 12 cases is as follows: 3 (25%) were given SNRIs (1 censored), 4 (33%) were administered SSRIs (2 censored), and 5 (42%) were treated with first-generation antidepressants. The median survival times for cases with SNRIs, SSRIs, and first-generation antidepressants were 2.0, 4.0, and 6.0 months, respectively. The median survival time of patients with SNRIs was significantly shorter than those treated with first-generation antidepressants (log rank, P = .008) and relatively shorter than those with SSRIs (log rank, P = .090). Furthermore, the median survival time of patients receiving SSRIs was nonsignificantly shorter than those with the first-generation antidepressants (log rank, P = .615).

Predictors of Survival Time in Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Patients With Depression

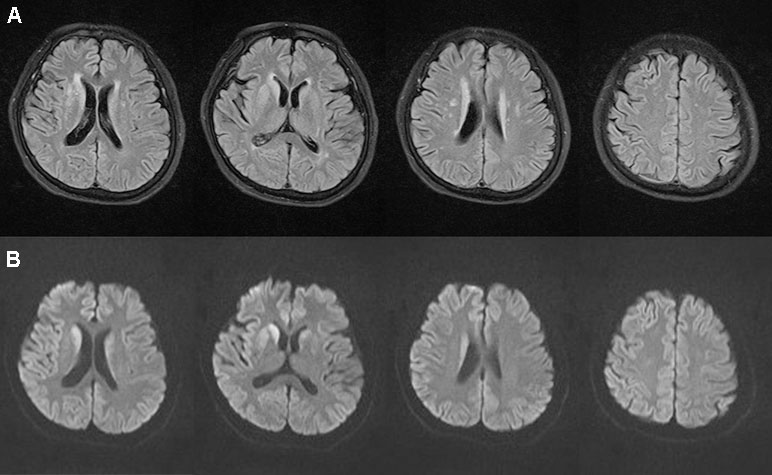

The Cox regression model including age and antidepressant types (Table 1) was preferred (likelihood ratio test, deviance = 25.469; score test, P = .043). Compared to first-generation antidepressants, the use of SNRIs [hazard ratio (HR), 23.028; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.401 to 378.461; P = .028] remained independently associated with significantly shorter survival time in sCJD patients with depression.

Discussion

Since depression is one of the most common global mental health conditions, the use of antidepressant drugs has increased dramatically with almost half of the prescriptions being for some off-label indication (36). However, our investigation revealed that almost none of the sCJD patients experienced any relief of their depressive symptoms after the antidepressant treatment. Furthermore, the median survival time of sCJD patients receiving SNRI therapy was shorter than the average survival of sCJD patients (2.3 vs. 4.6–17.4 months) (16). Thus, antidepressants do not seem to have any beneficial effect on sCJD patients with depression, a finding consistent with previous clinical studies not only on sCJD patients but also those with dementia (10, 19). Likewise, the efficacy characteristics of antidepressants indicate that antidepressants appear to display relatively poor efficacy in people older than 65 years (37). Based on the neurotransmitter receptor hypothesis of antidepressant drugs, the amount of neurotransmitter changes rapidly after an antidepressant is administered. But the clinical effects appear only weeks later (usually 6–12 weeks) (37). Due to the rapid progress of the disease, sCJD patients often use antidepressants for only a brief period. Therefore, the drugs usually cannot achieve clinical efficacy but are instead likely to exert unwanted side effects.

The question arises as to why patients with sCJD receiving antidepressants seem to deteriorate faster. Since antidepressants mainly alter neurotransmitter levels, we postulate that this deterioration must be related to these changes. Several independent lines of evidence support this postulation. sCJD resembles the degenerative dementias. Studies of AD, the best-known of the degenerative dementias, have proved that the accumulations of β-amyloid (Aβ) and tau proteins damage neurons and synapses, whereas the change in neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine (ACh) occurs at the initial stage (38). Similarly, the cause of sCJD neuropathological changes has also proved to be a reversible process, such as synaptic or neuronal dysfunction (39). Interestingly, patients with sCJD also have higher concentrations of Aβ and tau proteins in their serum and CSF (40, 41). Aβ may be propagated in a prion-like manner (42, 43). Similar observations have been made for tau (44). Because sCJD and AD share these common features (45), perhaps we can also attempt to delay the progress of sCJD by regulating the level of neurotransmitters. Furthermore, the typical lesions in MRI and histologic appearance in sCJD consist of cortical, basal ganglia, and cerebellum (46, 47). It was observed that the clinical target areas in the brainstem of prion-infected mice were the locus coeruleus, the nucleus of the solitary tract, and the pre-Bötzinger complex (48). These brain areas are exactly those in which the neuronal cell bodies generating neurotransmitters are mainly located or the areas innervated by their axonal projections.

How do these neurotransmitters modulate disease progression? According to our study, the survival period of sCJD patients is related to the type of antidepressants. By analyzing the pharmacological characteristics, we postulate that elevations in 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) may worsen the condition, although the sedative effects mediated by anti-histamine (HA), anti-ACh, and blockade of α-1 adrenoceptors may contribute to the relief of symptoms. Acute stimulation of the 5-HT can produce symptoms similar to sCJD (37). Neurotransmitters exist in many brain areas, but which area plays the key role? When SSRI treatment is initiated, the concentrations of 5-HT are elevated to a much greater extent at the somatodendritic area located in the midbrain raphe, rather than in the brain areas where the axons terminate (37). Therefore, SSRIs may exert more significant effects on the brainstem in patients with sCJD. However, the pathological changes in sCJD do not occur in the brainstem but rather in the projection pathways of neurotransmitters, such as cortical, basal ganglia, and cerebellum. This raises the question of how changes in the brainstem’s neurotransmitter activities affect other brain areas. Taking into account the symptoms (such as myoclonus that occurs at night, AM) of patients with sCJD, we postulate that one pathway through which brainstem’s neurotransmitter activities trigger cognitive impairment encountered in sCJD patients may be through its disruption of sleep centers in the brainstem. AM is a disorder caused by damage to the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) centered on the brainstem. Arousal is regulated by ARAS, which is influenced in large part by five key neurotransmitters: HA, dopamine (DA), NE, 5-HT, and ACh. Changes in these neurotransmitters can cause sleep disorders, i.e., rapid eye movement (REM) sleep without atonia (RSWA), and nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep disruption. Clinical studies have shown that SSRIs and SNRIs are associated with a higher prevalence of RSWA (49), explained in part by the theories about REM sleep initiation that advocate for a double switch model, possibly triggered by neurons located in the brainstem (50). Sleep disorders can cause many symptoms similar to sCJD, such as psychiatric symptoms (fear, anger, aggressive behavior, etc.), increased muscle tone, and most notably, cognitive impairment. For example, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is by far the strongest clinical predictor of onset of neurodegenerative diseases (51). The presence of RBD in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is associated with higher risk of cognitive decline (52). The reduced NREM slow-wave activity (SWA) generation was associated with impaired hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation (53). The Aβ burden in the medial prefrontal cortex correlates significantly with the severity of impairment in NREM SWA generation (53). Even one night of sleep deprivation could result in a significant increase in Aβ burden in the brain (54). Thus, the dual excitatory effects of 5-HT and NE may exacerbate the sleep deprivation encountered in sCJD patients, causing a cascading effect and then triggering cognitive impairment.

Why is the effect of neurotransmitters so rapid in sCJD patients? One reason may be the pathological overactivity of the brain’s serotonergic system in this disease. This hypothesis is supported by the evidence that the mean tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH)-positive cell size was significantly greater and cells were more intensely stained in CJD compared to controls (55). This may result in an increase in release of 5-HT. Coupled with the cascade effect of neurotransmitters, the actual effects may be amplified. The increase in 5-HT also reduced the release of DA in the prefrontal zone by negative feedback regulation (37). The reduction of DA may cause some symptoms similar to sCJD, such as cognitive impairment and apathy. Another reason could be that synapses in sCJD may be more vulnerable. The pathological features of CJD indicate that the vacuole in the cytoplasm is the cystic dilation of neurons and necrosis of the necrotic membrane. The cell membrane damage of CJD seems to be more serious than AD, where amyloid plaques form outside the neurons and neuron fibers entangle within the neurons. Damage to the synaptic membrane leads to a decrease in neurotransmitter receptors. In response to this change, the remaining receptors may be in a hypersensitivity state, or the number of receptors may increase (37), which may further enhance the effects of neurotransmitters such as 5-HT.

Many of the families of patients with sCJD complain of the delay in diagnosis and the plethora of misdiagnoses (56). Expediating a sCJD diagnosis is of great significance. Almost half of patients were misdiagnosed first as “psychiatric patients” (57). Consequently, it is very important for psychiatrists to consider CJD among the possible differential diagnoses in elderly patients. Our investigation suggests that it may be helpful to use imaging such as functional MRI and positron emission computed tomography (PET) to detect earlier changes in patients with sCJD.

Of course, our study has some limitations. First, the number of available cases is too small, and in many cases, the description of psychiatric symptoms and details of the antidepressants were inadequate. Second, because case reports tend to report exceptional situations, there is inevitably some bias. However, we think it is a reasonable approach to study CJD by undertaking case analysis or studies of one single individual. Due to the rapid progression of CJD, studies on population samples often overlook certain unique changes.

Investigations into sCJD have mainly focused on autopsy-based pathology, but little is known about neurophysiological changes. We hope this study will draw attention to the depressive symptoms of sCJD patients and the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms.

Conclusions

The use of antidepressants was associated with a shorter survival time of sCJD patients, especially the use of SNRIs. The possible neurotransmitter changes may be due to a pathophysiological mechanism in CJD. Functional imaging and use of the polysomnogram to detect earlier changes in sCJD patients may be worth trying.

Ethics Statement

This case study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Ethical Committee of China Medical University. The case study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University. The subject gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was also obtained from each patient for the publication of this case report.

Author Contributions

CZ had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CZ and YLia contributed to the study concept and design. YLi contributed to the case report. YLia, YLi, MG, and SZ contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. YLia, HW, and XC drafted the manuscript. CZ conducted the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors performed the statistical analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by The Liaoning Province Key Research and Development Project Critical Project (no. 2017225005, CZ), The Shenyang Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology International Exchange and Cooperation Project (no. 17-129-6-00, CZ), and China Medical University High-level Innovation Team Training Plan (no. 2017CXTD02, CZ).

Conflict of Interest Statements

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00297/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Steffens DC, Fisher GG, Langa KM, Potter GG, Plassman BL. Prevalence of depression among older Americans: the Aging, Demographics and Memory Study. Int Psychogeriatr (2009) 21:879–88. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990044

2. WHO. Dementia. Fact sheet [Updated December 2017]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2017). Available at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs362/en/

3. Caraci F, Copani A, Nicoletti F, Drago F. Depression and Alzheimer’s disease: neurobiological links and common pharmacological targets. Eur J Pharmacol (2010) 626:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.022

4. Masters MC, Morris JC, Roe CM. “Noncognitive” symptoms of early Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal analysis. Neurology (2015) 84:617–22. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001238

5. Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief, no. 283. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics (2017). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db283.pdf

6. Dawes SE, Palmer BW, Meeks T, Golshan S, Kasckow J, Mohamed S, et al. Does antidepressant treatment improve cognition in older people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and comorbid subsyndromal depression. Neuropsychobiology (2012) 65:168–72. doi: 10.1159/000331141

7. Kessing LV, Forman JL, Andersen PK. Do continued antidepressants protect against dementia in patients with severe depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol (2011) 26:316–22. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32834ace0f

8. Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Han D, Leoutsakos JS, Lyketsos CG, Rabins PV, et al. The association of psychotropic medication use with the cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2012) 27:1248–57. doi: 10.1002/gps.3769

9. Årdal G, Hammar Å. Is impairment in cognitive inhibition in the acute phase of major depression irreversible? Results from a 10-year follow-up study. Psychol Psychother (2011) 84:141–50. doi: 10.1348/147608310X502328

10. Moraros J, Nwankwo C, Patten SB, Mousseau DD. The association of antidepressant drug usage with cognitive impairment or dementia, including Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety (2017) 34:217–26. doi: 10.1002/da.22584

11. Lee CW, Lin CL, Sung FC, Liang JA, Kao CH. Antidepressant treatment and risk of dementia: a population-based, retrospective case–control study. J Clin Psychiatry (2016) 77:117–22. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09580

12. Kessing LV, Søndergård L, Forman JL, Andersen PK. Antidepressants and dementia. J Affect Disord (2009) 117:24–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.020

13. Wang C, Gao S, Hendrie HC, Kesterson J, Campbell NL, Shekhar A, et al. Antidepressant use in the elderly is associated with an increased risk of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord (2016) 30:99–104. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000103

14. Ladogana A, Puopolo M, Croes EA, Budka H, Jarius C, Collins S, et al. Mortality from Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and related disorders in Europe, Australia, and Canada. Neurology (2005) 64:1586–91. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000160117.56690.B2

15. Mead S, Stumpf MP, Whitfield J, Beck JA, Poulter M, Campbell T, et al. Balancing selection at the prion protein gene consistent with prehistoric kurulike epidemics. Science (2003) 300:640–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1083320

16. Chen C, Dong XP. Epidemiological characteristics of human prion diseases. Infect Dis Poverty (2016) 5:47. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0143-8

17. Krasnianski A, Bohling GT, Harden M, Zerr I. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in Germany. J Clin Psychiatry (2015) 76:1209–15. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08915

18. Rabinovici GD, Wang PN, Levin J, Cook L, Pravdin M, Davis J, et al. First symptom in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Neurology (2006) 66:286–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000196440.00297.67

19. Wall CA, Rummans TA, Aksamit AJ, Krahn LE, Pankratz VS. Psychiatric manifestations of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: a 25-year analysis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci (2005) 17:489–95. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.4.489

21. Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, Romero C, Taratuto A, Heinemann U, et al. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Brain (2009) 132:2659–68. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp191

22. OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford 2011 levels of evidence. Oxford, England: Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (2016). Available at www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

23. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med (2009) 151:264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

24. Azorin JM, Donnet A, Dassa D, Gambarelli D. Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease misdiagnosed as depressive pseudodementia. Compr Psychiatry (1993) 34:42–4. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(93)90034-2

25. Goetz KL, Price TR. Electroconvulsive therapy in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Convuls Ther (1993) 9:58–62.

26. González-Duarte A, Medina Z, Balaguer RR, Calleja JH. Can prion disease suspicion be supported earlier? Clinical, radiological and laboratory findings in a series of cases. Prion (2011) 5:201–7. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.3.16187

27. Grande I, Fortea J, Gelpi E, Flamarique I, Udina M, Blanch J, et al. Atypical Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease evolution after electroconvulsive therapy for catatonic depression. Case Rep Psychiatry (2011) 2011:791275. doi: 10.1155/2011/791275

28. Jardri R, DiPaola C, Lajugie C, Thomas P, Goeb JL. Depressive disorder with psychotic symptoms as psychiatric presentation of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: a case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (2006) 28:452–4. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.05.005

29. Jiang TT, Moses H, Gordon H, Obah E. Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease presenting as major depression. South Med J (1999) 92:807–8. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199908000-00012

30. Milanlioglu A, Ozdemir PG, Cilingir V, Ozdemir O. Catatonic depression as the presenting manifestation of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. J Neurosci Rural Pract (2015) 6:122. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.143220

31. Muayqil T, Siddiqi ZA. Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease with worsening depression and cognition. Can J Neurol Sci (2007) 34:464–6. doi: 10.1017/S031716710000737X

32. Onofrj M, Fulgente T, Gambi D, Macchi G. Early MRI findings in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. J Neurol (1993) 240:423–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00867355

33. Power B, Trivedi D, Samuel M. What psychiatrists should know about sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Australas Psychiatry (2012) 20:61–6. doi: 10.1177/1039856211430145

34. Wang YT, Wu CL. Probable sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease mimicking a catatonic depression in an elderly adult. Psychogeriatrics (2017) 17(6):524–5. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12264

35. Yang HY, Huang SS, Lin CC, Lan TH, Chan CH. Identification of a patient with sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in a psychiatric ward. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2013) 67:280–1. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12049

36. Wong J, Motulsky A, Abrahamowicz M, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Tamblyn R. Off-label indications for antidepressants in primary care: descriptive study of prescriptions from an indication based electronic prescribing system. BMJ (2017) 356:j603. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j603

37. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 4th ed. New York: Cambridge University Press (2014).

38. Wang L, Benzinger TL, Su Y, Christensen J, Friedrichsen K, Aldea P, et al. Evaluation of tau imaging in staging Alzheimer disease and revealing interactions between β-amyloid and tauopathy. JAMA Neurol (2016) 73:1070–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2078

39. Soto C, Satani N. The intricate mechanisms of neurodegeneration in prion diseases. Trends Mol Med (2011) 17:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.09.001

40. Thompson AGB, Luk C, Heslegrave AJ, Zetterberg H, Mead SH, Collinge J, et al. Neurofilament light chain and tau concentrations are markedly increased in the serum of patients with sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, and tau correlates with rate of disease progression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2018) 89(9):955–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317793

41. Leitão MJ, Baldeiras I, Almeida MR, Ribeiro MH, Santos AC, Ribeiro M, et al. CSF Tau proteins reduce misdiagnosis of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease suspected cases with inconclusive 14-3-3 result. J Neurol (2016) 263:1847–61. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8209-x

42. Frontzek K, Lutz MI, Aguzzi A, Kovacs GG, Budka H. Amyloid-β pathology and cerebral amyloid angiopathy are frequent in iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease after dural grafting. Swiss Med Wkly (2016) 146:w14287. doi: 10.4414/smw.2016.14287

43. Jucker M, Walker LC. Neurodegeneration: amyloid-β pathology induced in humans. Nature (2015) 525:193–4. doi: 10.1038/525193a

44. Alonso AD, Beharry C, Corbo CP, Cohen LS. Molecular mechanism of prion-like tau-induced neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement (2016) 12:1090–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.014

45. Debatin L, Streffer J, Geissen M, Matschke J, Aguzzi A, Glatzel M. Association between deposition of beta-amyloid and pathological prion protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Neurodegener Dis (2008) 5:347–54. doi: 10.1159/000121389

46. Fragoso DC, Gonçalves FAL, Pacheco FT, Barros BR, Aguiar LI, Nunes RH, et al. Imaging of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: imaging patterns and their differential diagnosis. Radiographics (2017) 37:234–57. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160075

47. Liberski PP. Spongiform change—an electron microscopic view. Folia Neuropathol (2004) 42 Suppl B:59–70.

48. Mirabile I, Jat PS, Brandner S, Collinge J. Identification of clinical target areas in the brainstem of prion-infected mice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol (2015) 41:613–30. doi: 10.1111/nan.12189

49. Lee K, Baron K, Soca R, Attarian H. The prevalence and characteristics of REM sleep without atonia (RSWA) in patients taking antidepressants. J Clin Sleep Med (2016) 12:351–5. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5582

50. Peever J, Luppi PH, Montplaisir J. Breakdown in REM sleep circuitry underlies REM sleep behavior disorder. Trends Neurosci (2014) 37:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.02.009

51. Iranzo A, Molinuevo JL, Santamaría J, Serradell M, Martí MJ, Valldeoriola F, et al. Rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder as an early marker for a neurodegenerative disorder: a descriptive study. Lancet Neurol (2006) 5:572–7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70476-8

52. Vendette M, Gagnon JF, Décary A, Massicotte-Marquez J, Postuma RB, Doyon J, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder predicts cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease without dementia. Neurology (2007) 69:1843–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000278114.14096.74

53. Mander BA, Marks SM, Vogel JW, Rao V, Lu B, Saletin JM, et al. β-Amyloid disrupts human NREM slow waves and related hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation. Nat Neurosci (2015) 18:1051–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.4035

54. Shokri-Kojori E, Wang GJ, Wiers CE, Demiral SB, Guo M, Kim SW, et al. β-Amyloid accumulation in the human brain after one night of sleep deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2018) 115:4483–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721694115

55. Fraser E, McDonagh AM, Head M, Bishop M, Ironside JW, Mann DM. Neuronal and astrocytic responses involving the serotonergic system in human spongiform encephalopathies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol (2003) 29:482–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00486.x

56. Paterson RW, Torres-Chae CC, Kuo AL, Ando T, Nguyen EA, Wong K, et al. Differential diagnosis of Jakob–Creutzfeldt disease. Arch Neurol (2012) 69:1578–82. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.79

Keywords: depression, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, antidepressant, neurotransmitters, sleep wake disorders

Citation: Liang Y, Li Y, Wang H, Cheng X, Guan M, Zhong S and Zhao C (2019) Does the Use of Antidepressants Accelerate the Disease Progress in Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Patients With Depression? A Case Report and A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 10:297. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00297

Received: 04 October 2018; Accepted: 16 April 2019;

Published: 03 May 2019.

Edited by:

Yi Yang, First Affiliated Hospital of Jilin University, ChinaReviewed by:

Michael X. Zhu, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, United StatesYan-Jiang Wang, Third Military Medical University, China

Copyright © 2019 Liang, Li, Wang, Cheng, Guan, Zhong and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chuansheng Zhao, Y3N6aGFvQGNtdS5lZHUuY24=

Yifan Liang

Yifan Liang Yan Li

Yan Li Chuansheng Zhao

Chuansheng Zhao