- Department for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Introduction: Although informal coercion is frequently applied in psychiatry, its use is discussed controversially. This systematic review aimed to summarize literature on attitudes toward informal coercion, its prevalence, and clinical effects.

Methods: A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, PsycINF, and Google Scholar was conducted. Publications were included if they reported original data describing patients’ and clinicians’ attitudes toward and prevalence rates or clinical effects of informal coercion.

Results: Twenty-one publications out of a total of 162 articles met the inclusion criteria. Most publications focused on leverage and inducements rather than persuasion and threat. Prevalence rates of informal coercion were 29–59%, comparable on different study sites and in different settings. The majority of mental health professionals as well as one-third to two-third of the psychiatric patients had positive attitudes, even if there was personal experience of informal coercion. We found no study evaluating the clinical effect of informal coercion in an experimental study design.

Discussion: Cultural and ethical aspects are associated with the attitudes and prevalence rates. The clinical effect of informal coercion remains unclear and further studies are needed to evaluate these interventions and the effect on therapeutic relationship and clinical outcome. It can be hypothesized that informal coercion may lead to better adherence and clinical outcome but also to strains in the therapeutic relationship. It is recommendable to establish structured education about informal coercion and sensitize mental health professionals for its potential for adverse effects in clinical routine practice.

Introduction

Informal coercion is ubiquitous in the health-care system, especially in mental health and psychosocial services. It comprises a large range of treatment pressures and interventions that can be applied by the professional with the intention to foster treatment adherence or avoid formal coercion. The degree of coercion adherent to several interventions ranges between full autonomy and formal coercion that is regulated by the law. Generally, informal coercion is intertwined with the therapeutic relationship and frequently applied by the professional unintentionally (1). The intensity of coercion that is perceived by the patient consecutively interacts with various aspects, such as transparency, fairness, dignity, trust, and the quality of the therapeutic alliance itself (2). Therefore, perceived coercion does not necessarily correlate with factual coercion, both formal and informal (3, 4).

The spectrum of informal coercive measures constitutes a continuum of phenomena, ranging from subtle interpersonal interactions to obvious demonstrations of force. Several graduations of informal coercion have been described, and the most commonly used categorizations are as follows: Szmukler and Appelbaum (5) defined a hierarchy of treatment pressures with: (I) persuasion; (II) interpersonal leverage; (III) inducements; (IV) threats; and (V) compulsory treatment. More detailed, Lidz et al. (6) defined nine graduations of coercion: (I) persuasion, (II) inducement, (III) threats, (IV) show of force, (V) physical force, (VI) legal force, (VII) request for a dispositional preference, (VIII) giving orders, and (IX) deception.

Beyond full autonomy, persuasion and conviction are the least problematic interventions on the spectrum of treatment pressures as it relies on respect for the patient’s values and arguments. It is a very common phenomenon in the interaction of patients and professionals and is also compatible with a therapeutic relationship that aims at an informed consent and a shared decision-making process (7). Persuasion can be differentiated from conviction by the nuance that conviction targets on the result that the patient comes to own conclusions during a reciprocal discussion while persuasion results in the adoption of the professional’s opinion by the patient.

Ascending in the hierarchy of treatment pressures, the notion of professional force becomes more obvious resulting in a more asymmetrical therapeutic relationship. There is a range of utilitarian interventions that are applicable on the basis of emotional or factual dependency of the patient within the professional relation. Interpersonal leverage may occur if the patient shows emotional dependency on the professional which may be used for interpersonal pressure. The clinician expresses verbally or non-verbally his or her expectations or demonstrates disappointment. The patient is tempted to react in a way that he or she assumes would please the clinician. A more factual form of leverage is the use of inducements within a framework of negotiation. Thereby, the patient is demanded to comply with treatment in exchange for a desired asset. Several goods or values can be used as leverage tools. Monahan et al. (8) described four specific types of leverage: housing, money, children, and criminal justice. Other types, such as work, non-monetary goods, attention, and care, are probably common in the health-care system as well. A fluent transition from offer to threat in this context seems obvious. A distinction can be made considering the normative basic entitlement. If the patient could receive a desired good in addition to standard care or basic rights, it can be called an offer. If some basic right or standard good is withheld from the patient, it is considered a threat (9). Thus, the classification of the proposition made by the professional strongly depends on the factual, legal, or moral baseline (10, 11). Although the differentiation between offer and threat may be difficult within the spectrum of leverage tools, there are a range of obvious threats comprising a more subtle demonstration of force up to announcement of negative sanctions.

To date, there is no comprehensive digest on informal coercion in mental health-care systems. Therefore, the aim of this study was to review the literature on prevalence of treatment pressures and informal coercion and the attitudes toward and clinical consequences of these interventions from the perspective of patients and professionals.

Our hypothesis was that evidence on informal coercion is scarce and mainly refers to prevalence and attitudes rather than to clinical effects. Additionally, we hypothesized that the literature relies mostly on cross-sectional studies, and studies of higher quality such as randomized controlled trials would be absent due to the complexity of operationalization and ethical reasons that might prevent an interventional study.

Materials and Methods

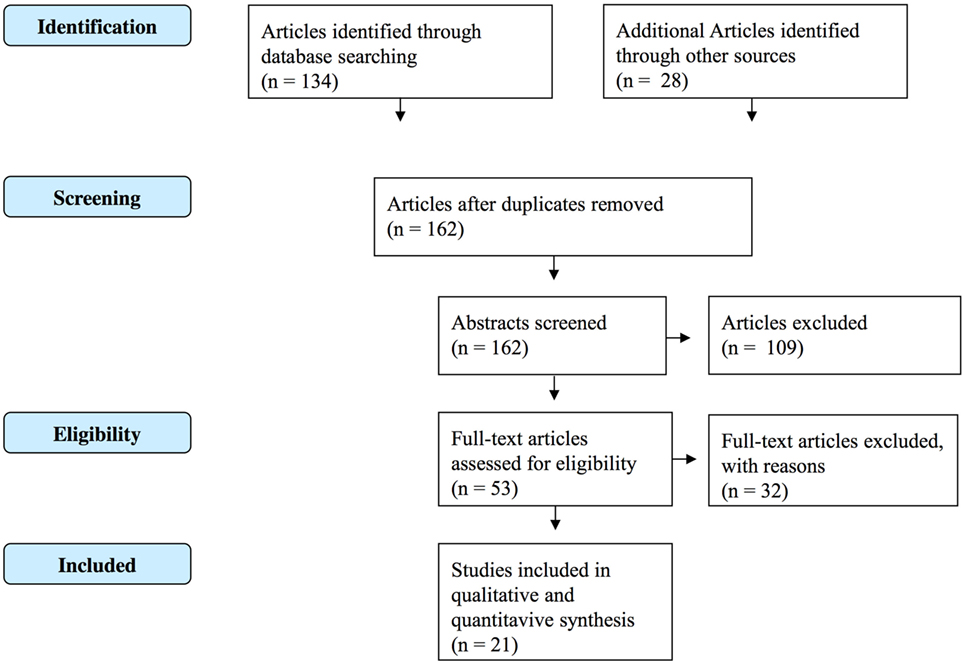

A systematic strategy was used to search the electronic databases PubMed/Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar for studies published after the year 2000. A subject and text word search strategy was used with the words “informal coercion,” OR “treatment pressure,” OR leverage. Those words were combined with psychiatr* OR psychiatry OR “mental health.” References of the included studies and other reviews related to this topic were also inspected and relevant articles were included (referred to as “other sources” in Figure 1).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies containing original data describing patients’ and/or clinicians’ attitudes toward informal coercion were included. Also studies evaluating the prevalence and clinical effects of informal coercion were included. Regarding the low number of publications in this very specific topic, no quality threshold for inclusion was set. Only studies published after the year 2000 were included. Relevant articles were filtered according to the Prisma-statement (12) (Figure 1). Studies focusing on formal/legal coercion were excluded except when they did have explicit aims to investigate informal coercion in the context of legally involuntary in- or outpatient treatment. Studies on perceived coercion were included when conducted in the context of informal coercion, but excluded in the context of formal coercion.

Analysis

The following categories were built to classify studies by themes. (I) Attitudes of staff to informal coercion in in- and outpatient settings. (II) Attitudes of patients toward informal coercion in in- and outpatient settings. (III) Prevalence of informal coercion. (IV) Clinical effects/aspects of informal coercion.

The quality of the included studies was assessed according to a hierarchy of evidence (categorizing studies by the attributes of their design) and the relevance for the topic as described in the results chapter. The results are partially categorized and summarized in a narrative way.

Results

The search procedure yielded 162 articles. Of these, 21 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The 21 publications referred to 15 studies [1 study resulted in 2 (13, 14), another study in 6 publications (15–20), and 13 studies in 1 publication (21–33)].

Quality of the Studies Included

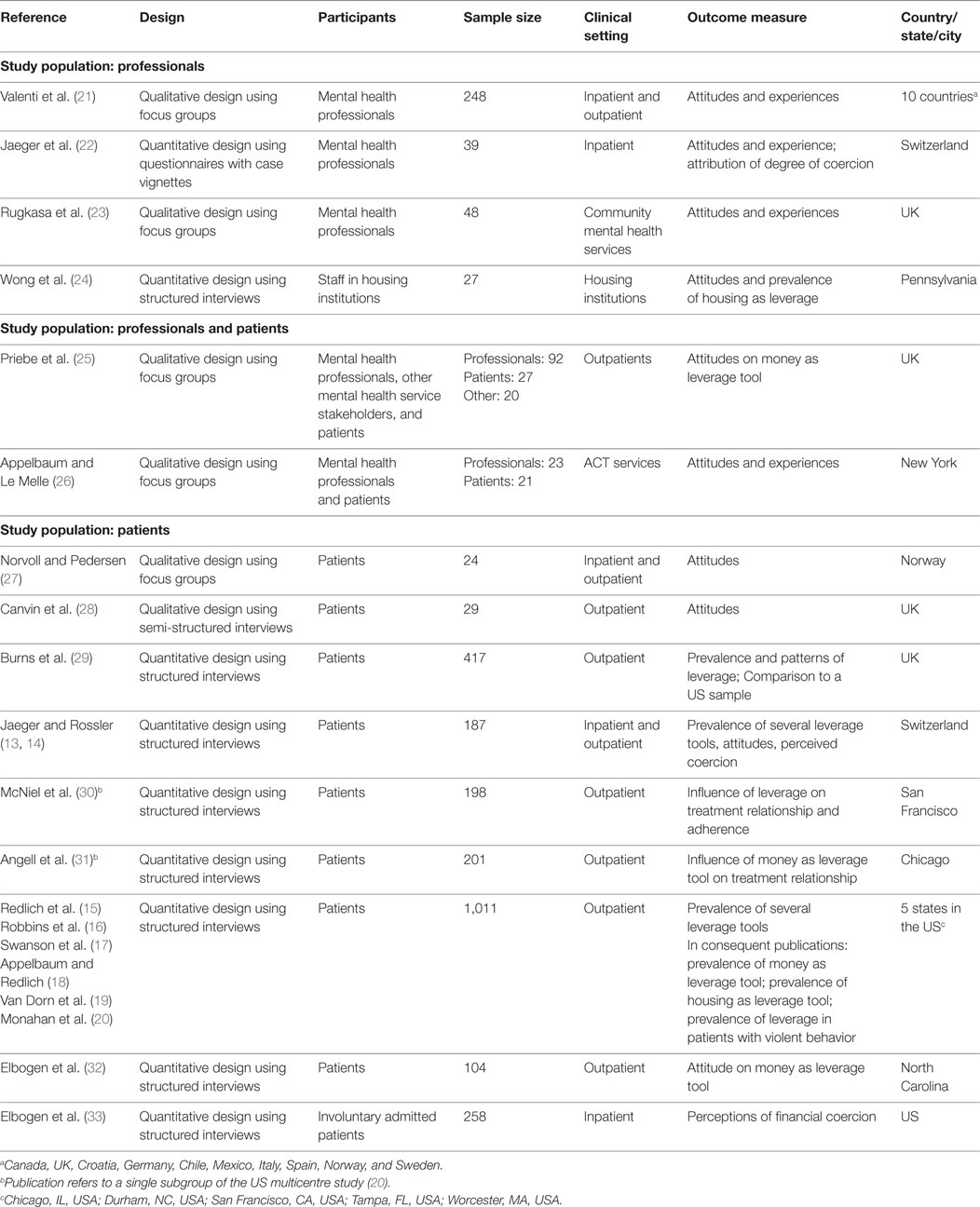

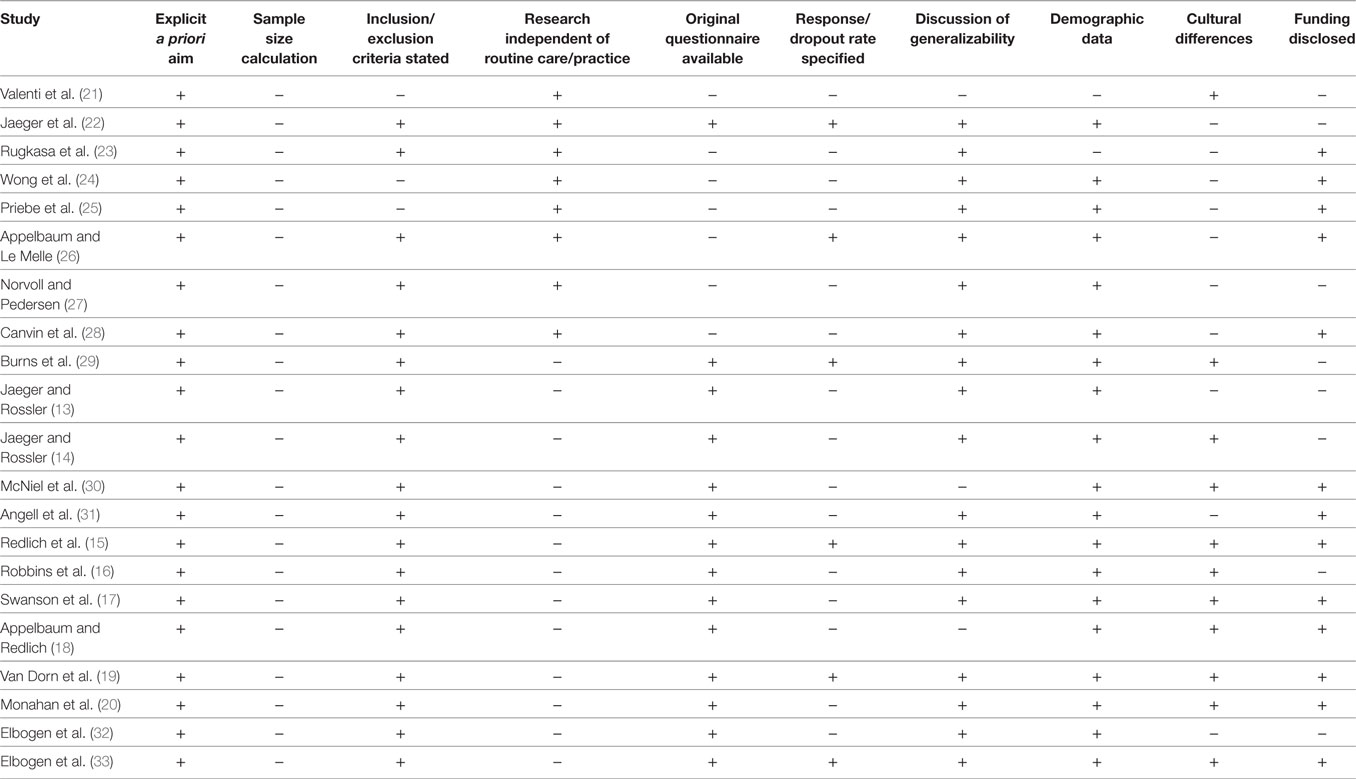

All studies included were cross sectional (Table 1). No experimental or quasi-experimental studies were found. Four studies assessed mental health professionals only, thereof two using focus group interviews, one using case vignettes and one using structured interviews. Two studies used focus groups with professionals and patients. Nine studies assessed patients only, most of them using structured individual interviews, and one using focus groups, another using individual qualitative interviews. The sample sizes varied between 24 and 1,011 participants. Professionals were from several settings including in- and outpatient services, ACT, and housing institutions. Most patients were recruited in outpatient setting, three studies also included inpatients.

All publications had explicit a priori aims, and 17 discussed their data in the context of generalizability. None of the studies used a sample size calculation or justified the number of participants (Table 2). None of the studies declared dropouts. The nature of funding sources was disclosed in 13 out of 21 publications. The questionnaires were described conclusively in all publications that used structured interviews. Most studies assessed demographic parameters of the participants. Some studies found and discussed cultural differences in the prevalence of informal coercion and discussed these findings. One study especially aimed to investigate cultural differences in the prevalence of informal coercion between the UK and the US.

Almost all studies examined attitudes toward informal coercion. Four studies, one from the UK, two from the US, and one from Switzerland, evaluated the prevalence of several interventions comprising informal coercion, mostly leverage tools. Most of the studies examined leverage as one form of informal coercion in one of the following categories: housing, justice, childcare, employment, and money. Studies searching for informal coercion in general or leverage without categorization were rare. There were no interventional studies assessing the clinical effect of informal coercion.

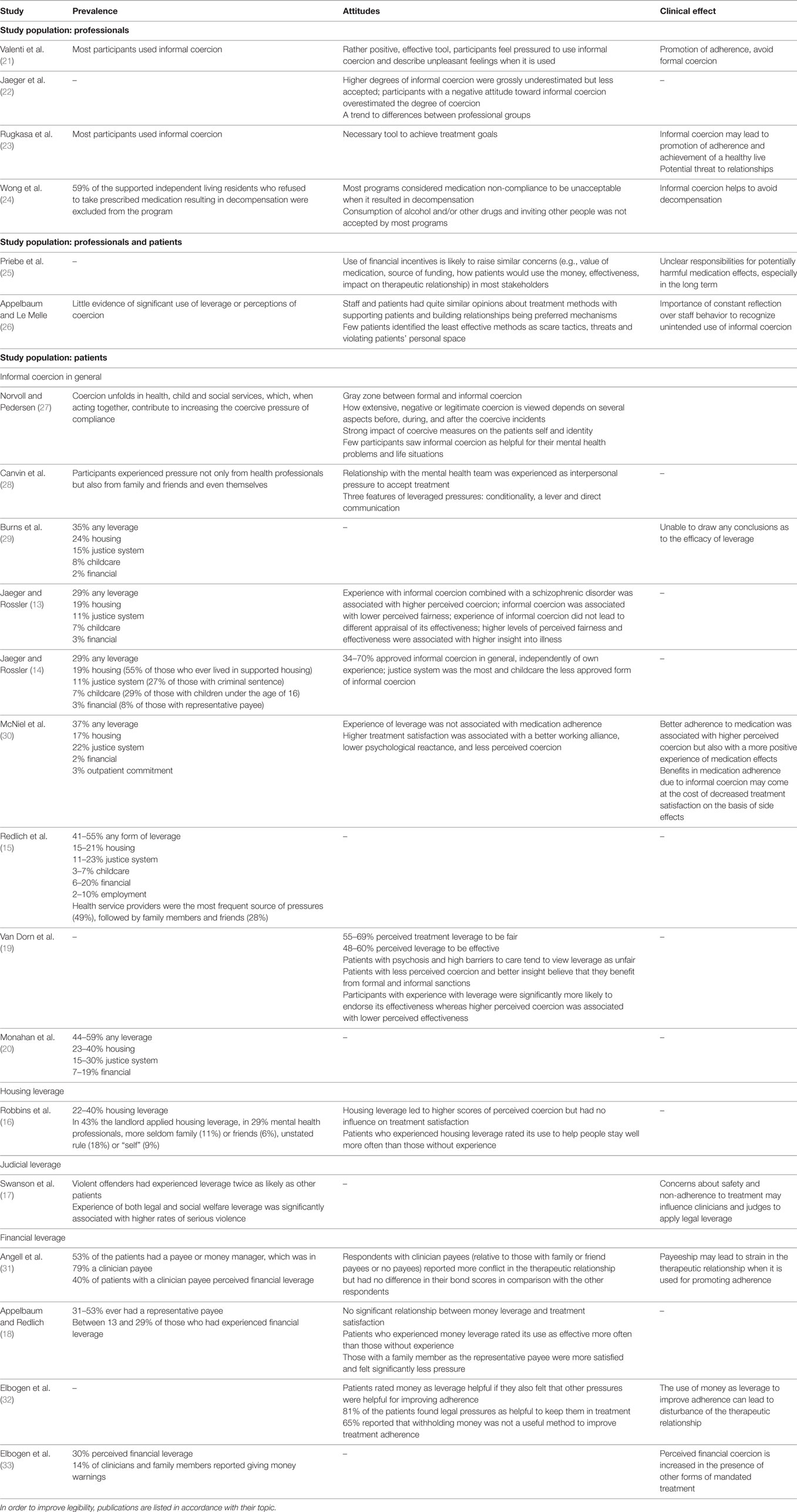

The Perspective of Mental Health Professionals on Informal Coercion

Studies assessing mental health professionals did not evaluate specific prevalence rates. The four publications consistently stated that “most” of the professionals used informal coercion in daily routine practice (Table 3). The study investigating housing facilities found that about 60% of malcompliant residents were excluded from the program suggesting a frequent and incisive use of pressure to treatment adherence (24). Professionals intended to foster their patients’ ability to take responsibility for their lives and considered informal coercion as a justifiable method to reach this goal (23). Concerning clinical effects, participants considered informal coercion to be effective in the therapeutic process with respect to promotion of adherence resulting in avoidance of decompensation as well as formal coercion. Nevertheless, one study revealed that interventions with stronger informal coercion were less accepted by mental health professionals (22), and mental health professionals tended to avoid informal coercion and to respect the patients’ decisions if possible although some stated to feel being pressured to use it. Some participants used informal coercion more often than they were aware to use it (21), and one study revealed that the degree of coercion was underestimated in the whole study population. Detailed analysis showed differences in the underestimation of professions with physicians showing the least underestimation of the degree of coercion followed by nurses and other professions (22). Telling patients what to do, being judgmental, and threatening them were rated as the least successful methods (26). If informal coercion was used in the framework of negotiation and asserting authority, it was referred to as suitable to reach treatment goals.

In summary, professionals rated informal coercion to be effective and useful in some situations, especially if it concerned interventions with less obvious and strong coercion. But the use of informal coercion was regarded as a critical intervention, and some participants stressed the importance of continuous reflection on the usage of informal coercion within treatment teams (to “keep each other in check”) (26) as well as individually. Possible alternatives, including less influence and coercion, were consistently favored. Nevertheless, it seems to be a frequently applied interventional approach within therapeutic interactions in psychiatric health care.

The Perspective of Patients on Informal Coercion

As opposed to the studies focusing on professionals, some publications investigating patients’ perspective on informal coercion were able to number the prevalence among the samples. Similar to the studies focusing on the professional perspective, these publications mainly reported results concerning leverage, rather than other forms of informal coercion. Most studies investigated the prevalence of leverage tools in general as well as the prevalence of specific forms of leverage (Table 3). Money, housing, and work are used as leverage tools to induce treatment adherence within the social welfare system. An individual with mental disorder would only gain access to the desired support if psychiatric treatment, and/or medication, was accepted. In the context of the judicial system, similar circumstances might emerge when a psychiatric patient agrees to adhere to treatment in order to avoid prosecution or an unfavorable judicial order, such as incarceration. Individuals with children also might face restriction of their parental rights if they do not consent to psychiatric treatment. Twenty-nine to fifty-nine percent of the patients from several study sites reported the experience of any form of leverage. The lowest rates were found in Switzerland and the highest in the US. The most frequently used leverage tool was housing with rates from 15 to 40% of all patients. Financial leverage was reported by 2–30%. Employment was only assessed in one US study, and 2–10% of the study participants reported experience. The prevalence rates of judicial leverage tools ranged from 11 to 23% and childcare was used in 3–8%. Health-care providers were identified as the most prevalent sources of treatment pressures next to family members, friends, and payees among others. Canvin et al. (28) found that patients experienced pressure not solely in mental health care but in everyday life with family and friends.

Attitudes toward informal coercion were examined by most of the studies including general appraisal, evaluation of fairness, and effectiveness. Thirty-four to eighty-one percent of the patients described different forms of leverage as helpful and approved its usage independently of their own experience (14, 19). The particular forms of leverage were rated differently with justice as most approved and children as less approved form (14). In one US study, 55–69% of the patients perceived the use of leverage as fair and 48–60% as effective (19). In some publications, those patients who experienced informal coercion tended to rate its effectivity higher than those without experience of informal coercion (13, 14, 16, 18, 19). Controversially, some qualitative studies reported that only a few patients found coercion to be helpful (27), and informal coercion was rated as the less successful compared to interventions on a merely voluntary basis (26).

Some studies which tended to characterize the participants showed that informal coercion was rated more positive by patients with higher insight (13, 19) and less perceived coercion (19) whereas experience of informal coercion and a schizophrenic disorder were associated with higher perceived coercion scores and lower perceived fairness (13, 19).

No study aimed primarily to evaluate the clinical effect of informal coercion in an experimental or quasi-experimental setting. Only subjective ratings on the effectiveness of informal coercion were assessed in some studies as mentioned above.

Discussion

Prevalence of Informal Coercion

This systematic review shows that informal coercion is used as a method to enhance treatment adherence in different countries and with a high prevalence according to investigations among patients as well as professionals. Most frequently, different forms of leverage were evaluated rather than other interventions comprising informal coercion (i.e., persuasion, threat). One-third to half of the patients reported having been subjected to some sort of leverage within interactions in psychiatric therapy and care. Also, most of the professionals stated to use leverage and other forms of informal coercion within their therapeutic activities. The supported housing sector appeared to be associated the most with the use of leverage next to the criminal and civil justice sectors. Money and work were not as frequently reported as leverage tools. The most prevalent requirement to adhere to psychiatric treatment and medication for getting access to a supported housing facility might be regarded as structural informal coercion within the mental health-care system (34). The use of leverage within the justice system on the other hand works as a coercive informal admission to the mental health-care sector. Both pathways supposedly lead to an increased rate of patients who are at least not completely voluntarily in treatment. This routine link between mental health care and other societal sectors most likely contributes to the stigma that coercion is inherently attached to mental health care. Vice versa, this stigma of coercion might induce the use of the mental health-care system as a leverage tool to achieve non-medical aims. Nevertheless, informal coercion seems to result in a higher rate of psychiatric treatment of those in need (35) and to better outcome according to the opinions of both, patients and professionals.

Attitudes toward Informal Coercion

Next to a rather high appraisal by patients and professionals of at least weaker forms of informal coercion, such as persuasion and leverage, the use of informal coercion was considered critical to interfere with the therapeutic relationship. If inducing high levels of perceived coercion and having a notion of unfairness, informal coercion might impede the therapeutic relationship and lead to dropouts from treatment (1). Moreover, by increasing the association of psychiatric care with the notion of coercion, informal coercion might result in avoidance of the mental health-care system of others (36). It is not known if the number of individuals conducted into the mental health-care system by informal coercion outweighs the number of those who refrain from mental health care due to fear of being subjected to coercion. Thus, the effect of informal coercion (as well as formal coercion) on public mental health and health-care costs is unknown.

If applied transparently and fairly, informal coercion was considered helpful and beneficial for personal recovery. Positive effects comprised improvement of adherence and clinical outcome as well as avoidance of decompensation and formal coercion. One-third to two-third of the patients approved informal coercion independently of their own experience (14, 19). Lucksted and Coursey showed that retrospectively some participants understood forced treatment to be in their best interest although they reported negative effects from it and wished to maintain the right to refuse treatment (37). These findings underline the controversy regarding informal coercion, which was also outlined by Norvoll and Pedersen where participants described informal coercion as part of a gray zone and only a few found it to be helpful for their mental health (27). Patients and other stakeholders with critical attitudes toward coercion would decidedly challenge the use of informal coercion at all and emphasize the importance of the reciprocal therapeutic relationship (38). The representativeness of the patients included in the studies of this review has to be considered as limited. It mostly comprises individuals who were in treatment within the mainstream public mental health-care systems (mostly institutional) rather than complementary, private, or other services. Also, the study patients consented to participate in the studies what implies a certain willingness to cooperate with the services. This is commonly considered a major limitation for representativeness of study participants in research on coercion in psychiatry.

Albeit, most professionals tended to avoid the use of informal coercion due to the ethical problems attached to interventions utilizing (formal and informal) coercion, and staff underlines the effectiveness of informal coercion to achieve better clinical outcomes in patients. In order to stay aware and reduce the use of informal coercion, continuous discussions on the issue and supervisions are rated to be helpful. However, it has to be assumed that many situations in which informal coercion is applied in routine practice the acting clinician would not be aware of using informal coercion (22). Corresponding to the included studies on patients’ perspective, professionals’ study participants might not be representative for mental health professionals in general. The willingness to participate in a study on the issue of coercion might be higher in professionals who are prone to critically reflect on delicate subjects as well as their own attitudes and routines.

Clinical Relevance of Informal Coercion

Our review revealed that no study evaluated the clinical effects of informal coercion as a primary outcome in an appropriate study design. This may be due to methodological as well as ethical problems attached to such a study. Psychiatric treatment is a complex and multifaceted process including many factors that may help the patient to recover. It seems difficult to set up a study design that would allow for a comparison of two similar groups of patients with one undergoing a treatment process including the use of informal coercion and another receiving the same treatment without informal coercion. It might be feasible to study different therapeutic attitudes in the treatment of a selected group of patients, e.g., individuals with psychosis concerning certain decision-making processes, such as choice of medication. In this context, an operationalized negotiation process could be applied to two groups of patients with one including persuasion and inducements and one on a merely informative basis. However, this would be highly artificial and disregard the individual nature and dynamic constitution of a sound therapeutic relationship that would be the basis of a realistic decision-making process. This would be a considerable limitation for the validity of the results of such a study.

Thus, it seems comprehensible that the studies reviewed in the present article refrain to the subjective evaluation of effectiveness of informal coercion interventions by professionals and patients. Although there are several studies reporting rather positive evaluations of clinical effects in terms of fostering adherence, clinical stability, and avoiding relapse, it is not possible to draw convincing conclusions. It seems highly dependent on some process-related aspects if informal coercion is accepted by patients as beneficial for their recovery. This includes a low level of perceived coercion, high perceived fairness, and sound procedural justice (39). Mental health professionals might miss the importance of these process-related factors and tend to hold a rather utilitarian attitude toward informal coercion. Thereby, professionals are at stake to contribute to the stigma of coercion in psychiatric treatment that might lead to avoidance of the mental health system (37). The use of financial or other forms of leverage may lead to unclear responsibilities for potentially harmful medication effects, especially in the long term (25). Additionally, benefits of coercively taken medication may be extenuated by decreased satisfaction with treatment (30).

Ethical and clinical guidelines for the use of informal coercion are crucial for raising and keeping awareness on the issue similarly to formal coercion. In fact, few contemporary guidelines on the use of coercion in health care amplified their scope beyond formal coercion on informal coercion (40). Accordingly, coercive interventions including informal coercion should only be applied under the restriction of commensurability, i.e., if less invasive interventions are not available or have proven not to be effective and the expected benefit outweighs the potential harm by the intervention itself. Autonomy of the patients must always be respected and prioritized when making a decision for a treatment or care intervention. Communication and documentation has to be transparent and appropriate (40). However, applying informal coercion in an ethically, legally, and therapeutically sound procedure requires the awareness that leverage and other forms of informal coercion are very frequently used in daily mental health-care routine. Mental health professionals should, therefore, be competent to realize when they apply informal coercion and know about the impact of informal coercion as well as ethical guidelines for the use of coercion. A more prominent place for the issue of informal coercion and the therapeutic relationship in educative curricula of mental health professionals as well as more in-depth qualitative and quantitative research on informal coercion have to be strongly recommended.

Limitations

The present systematic review provides a general overview on studies evaluating the prevalence, attitudes, and clinical effect concerning informal coercion. With respect to some important limitations, the results have to be interpreted with care. This review is merely descriptive, and no meta-analysis was intended or possible to conduct. Although the research was performed systematically, it is not known if all available publications were detected, especially the gray literature (i.e., research produced outside the academic publication channels). Most studies were conducted in the US and Europe. And although one study also included study sites in Canada, Chile, and Mexico, the results cannot be easily transferred to other countries or even regional contexts. Moreover, the methodological quality of the studies is limited, and no causal associations concerning clinical effects and consequences of informal coercion can be deducted. The use of informal coercion is supposedly interrelated with societal context, organization of the health-care system, the educational level of professionals, and many other factors that were not comprehensively controlled for in the included studies. Additionally, the representativeness of the samples was not evaluated. However, despite multiple limitations of the present review, some important aspects on informal coercion in mental health care can be concluded.

Conclusion

This is the first review on informal coercion in mental health care. Most studies focus on leverage in general and specific leverage tools in various clinical and non-clinical contexts. Remarkably, frequent experience with informal coercion was reported by both, professionals as well as patients. The attitudes were rather positive in professionals as well as in patients at least if informal coercion was applied according to a number of procedural aspects that are also included in ethical guidelines for coercive practices in medicine (respect for patient’s autonomy, procedural fairness, and transparency in communication). There is no evidence on the clinical effects of informal coercion but subjective evaluations on potential consequences, i.e., enhancement of adherence, promotion of clinical stability, and avoidance of relapse. Negative consequences such as increasing stigma of psychiatric services, impairment of the therapeutic relationship and consequent avoidance of mental health care are considered potential adverse effects.

Author Contributions

Conception and design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content: FH and MJ.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Theodoridou A, Schlatter F, Ajdacic V, Rossler W, Jaeger M. Therapeutic relationship in the context of perceived coercion in a psychiatric population. Psychiatry Res (2012) 200(2–3):939–44. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.012

2. Watson AC, Angell B. Applying procedural justice theory to law enforcement’s response to persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv (2007) 58(6):787–93. doi:10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.787

3. Bindman J, Reid Y, Szmukler G, Tiller J, Thornicroft G, Leese M. Perceived coercion at admission to psychiatric hospital and engagement with follow-up-a cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2005) 40(2):160–6. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0861-x

4. Sheehan KA, Burns T. Perceived coercion and the therapeutic relationship: a neglected association? Psychiatr Serv (2011) 62(5):471–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.62.5.471

5. Szmukler G, Appelbaum PS. Treatment pressures, leverage, coercion, and compulsion in mental health care. J Ment Health (2008) 17(3):233–44. doi:10.1080/09638230802156731

6. Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Hoge SK, Kirsch BL, Monahan J, Eisenberg M, et al. Factual sources of psychiatric patients’ perceptions of coercion in the hospital admission process. Am J Psychiatry (1998) 155(9):1254–60. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.9.1254

7. Adams JR, Drake RE, Wolford GL. Shared decision-making preferences of people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv (2007) 58(9):1219–21. doi:10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1219

8. Monahan J, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS, Hyde PS, Steadman HJ, Swartz MS. Mandated community treatment: beyond outpatient commitment. Psychiatr Serv (2001) 52(9):1198–205. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1198

9. Dunn M, Maughan D, Hope T, Canvin K, Rugkasa J, Sinclair J, et al. Threats and offers in community mental healthcare. J Med Ethics (2012) 38(4):204–9. doi:10.1136/medethics-2011-100158

11. Olsen DP. Influence and coercion: relational and rights-based ethical approaches to forced psychiatric treatment. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2003) 10(6):705–12. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00659.x

12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med (2009) 151(4):264–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

13. Jaeger M, Rossler W. Enhancement of outpatient treatment adherence: patients’ perceptions of coercion, fairness and effectiveness. Psychiatry Res (2010) 180(1):48–53. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.011

14. Jaeger M, Rossler W. [Informal coercion to enhance treatment adherence among psychiatric patients]. Neuropsychiatr (2009) 23(4):206–15. doi:10.5167/uzh-28070

15. Redlich AD, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC, Swanson JW. Use of the criminal justice system to leverage mental health treatment: effects on treatment adherence and satisfaction. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law (2006) 34(3):292–9.

16. Robbins PC, Petrila J, LeMelle S, Monahan J. The use of housing as leverage to increase adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Adm Policy Ment Health (2006) 33(2):226–36. doi:10.1007/s10488-006-0037-3

17. Swanson JW, Van Dorn RA, Monahan J, Swartz MS. Violence and leveraged community treatment for persons with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry (2006) 163(8):1404–11. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1404

18. Appelbaum PS, Redlich A. Use of leverage over patients’ money to promote adherence to psychiatric treatment. J Nerv Ment Dis (2006) 194(4):294–302. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000207368.14133.0c

19. Van Dorn RA, Elbogen E, Swanson J. Perceived fairness and effectiveness of leveraged community treatment among public mental health consumers in five U.S. cities. Int J Forensic Mental Health (2005) 4(2):119–33. doi:10.1080/14999013.2005.10471218

20. Monahan J, Redlich AD, Swanson J, Robbins PC, Appelbaum PS, Petrila J, et al. Use of leverage to improve adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Psychiatr Serv (2005) 56(1):37–44. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.37

21. Valenti E, Banks C, Calcedo-Barba A, Bensimon CM, Hoffmann KM, Pelto-Piri V, et al. Informal coercion in psychiatry: a focus group study of attitudes and experiences of mental health professionals in ten countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2015) 50(8):1297–308. doi:10.1007/s00127-015-1032-3

22. Jaeger M, Ketteler D, Rabenschlag F, Theodoridou A. Informal coercion in acute inpatient setting – knowledge and attitudes held by mental health professionals. Psychiatry Res (2014) 220(3):1007–11. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.014

23. Rugkasa J, Canvin K, Sinclair J, Sulman A, Burns T. Trust, deals and authority: community mental health professionals’ experiences of influencing reluctant patients. Community Ment Health J (2014) 50(8):886–95. doi:10.1007/s10597-014-9720-0

24. Wong YLI, Lee S, Solomon PL. Structural leverage in housing programs for people with severe mental illness and its relationship to discontinuance of program participation. Am J Psychiatr Rehabilitation (2010) 13(4):276–94. doi:10.1080/15487768.2010.523361

25. Priebe S, Sinclair J, Burton A, Marougka S, Larsen J, Firn M, et al. Acceptability of offering financial incentives to achieve medication adherence in patients with severe mental illness: a focus group study. J Med Ethics (2010) 36(8):463–8. doi:10.1136/jme.2009.035071

26. Appelbaum PS, Le Melle S. Techniques used by assertive community treatment (ACT) teams to encourage adherence: patient and staff perceptions. Community Ment Health J (2008) 44(6):459–64. doi:10.1007/s10597-008-9149-4

27. Norvoll R, Pedersen R. Exploring the views of people with mental health problems’ on the concept of coercion: towards a broader socio-ethical perspective. Soc Sci Med (2016) 156:204–11. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.033

28. Canvin K, Rugkasa J, Sinclair J, Burns T. Leverage and other informal pressures in community psychiatry in England. Int J Law Psychiatry (2013) 36(2):100–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.01.002

29. Burns T, Yeeles K, Molodynski A, Nightingale H, Vazquez-Montes M, Sheehan KA, et al. Pressures to adhere to treatment (‘leverage’) in English mental healthcare. Br J Psychiatry (2011) 199(2):145–50. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.086827

30. McNiel DE, Gormley B, Binder RL. Leverage, the treatment relationship, and treatment participation. Psychiatr Serv (2013) 64(5):431–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200368

31. Angell B, Martinez NI, Mahoney CA, Corrigan PW. Payeeship, financial leverage, and the client-provider relationship. Psychiatr Serv (2007) 58(3):365–72. doi:10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.365

32. Elbogen EB, Soriano C, Van Dorn RA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW. Consumer views of representative payee use of disability funds to leverage treatment adherence. Psychiatr Serv (2005) 56(1):45–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.45

33. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS. Psychiatric disability, the use of financial leverage, and perceived coercion in mental health services. Int J Forensic Mental Health (2003) 2(2):119–27. doi:10.1080/14999013.2003.10471183

34. Allen M. Waking Rip van Winkle: why developments in the last 20 years should teach the mental health system not to use housing as a tool of coercion. Behav Sci Law (2003) 21(4):503–21. doi:10.1002/bsl.541

35. Pescosolido BA, Gardner CB, Lubell KM. How people get into mental health services: stories of choice, coercion and “muddling through” from “first-timers”. Soc Sci Med (1998) 46(2):275–86. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00160-3

36. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hannon MJ. Does fear of coercion keep people away from mental health treatment? Evidence from a survey of persons with schizophrenia and mental health professionals. Behav Sci Law (2003) 21(4):459–72. doi:10.1002/bsl.539

37. Lucksted A, Coursey RD. Consumer perceptions of pressure and force in psychiatric treatments. Psychiatr Serv (1995) 46(2):146–52. doi:10.1176/ps.46.2.146

38. Johansson H, Eklund M. Patients’ opinion on what constitutes good psychiatric care. Scand J Caring Sci (2003) 17(4):339–46. doi:10.1046/j.0283-9318.2003.00233.x

39. Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, Elbogen EB. Consumers’ perceptions of the fairness and effectiveness of mandated community treatment and related pressures. Psychiatr Serv (2004) 55(7):780–5. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.780

Keywords: informal coercion, leverage, attitudes, prevalence, clinical effect, mental health, therapeutic relationship

Citation: Hotzy F and Jaeger M (2016) Clinical Relevance of Informal Coercion in Psychiatric Treatment—A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 7:197. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00197

Received: 12 October 2016; Accepted: 29 November 2016;

Published: 12 December 2016

Edited by:

Alexandre Wullschleger, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Mª Angeles Gomez Martínez, Pontifical University of Salamanca, SpainStephane Morandi, Centre hospitalier universitaire vaudois, Switzerland

Copyright: © 2016 Hotzy and Jaeger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthias Jaeger, bWF0dGhpYXMuamFlZ2VyQHB1ay56aC5jaA==

Florian Hotzy

Florian Hotzy Matthias Jaeger

Matthias Jaeger