- 1Department and Institute of Psychiatry, Medical School, University of São Paulo (USP) – The Equilibrium Program (TEP), São Paulo, Brazil

- 2Department and Institute of Psychiatry, Medical School, University of São Paulo (USP-PROTOC), São Paulo, Brazil

The maltreatment of children and adolescents is a global public health problem that affects high- and low-middle income countries (“LMICs”). In the United States, around 1.2 million children suffer from abuse, while in LMICs, such as Brazil, these rates are much higher (an estimated 28 million children). Exposition to early environmental stress has been associated with suboptimal physical and brain development, persistent cognitive impairment, and behavioral problems. Studies have reported that children exposed to maltreatment are at high risk of behavioral problems, learning disabilities, communication and psychiatric disorders, and general clinical conditions, such as obesity and systemic inflammation later in life. The aim of this paper is to describe The Equilibrium Program (“TEP”), a community-based global health program implemented in São Paulo, Brazil to serve traumatized and neglected children and adolescents. We will describe and discuss TEP’s implementation, highlighting its innovation aspects, research projects developed within the program as well as its population profile. Finally, we will discuss TEP’s social impact, challenges, and limitations. The program’s goal is to promote the social and family reintegration of maltreated children and adolescents through an interdisciplinary intervention program that provides multi-dimensional bio-psycho-social treatment integrated with the diverse services needed to meet the unique demands of this population. The program’s cost effectiveness is being evaluated to support the development of more effective treatments and to expand similar programs in other areas of Brazil. Policy makers should encourage early evidence-based interventions for disadvantaged children to promote healthier psychosocial environments and provide them opportunities to become healthy and productive adults. This approach has already shown itself to be a cost-effective strategy to prevent disease and promote health.

Introduction

Children and adolescent maltreatment is a global public health problem that affects high- and low-middle income countries (“LMICs”) (1–3). Globally, it is estimated that 6% of children under 18 (about 150 million individuals) are victims of maltreatment annually. In urban areas, it is estimated that tens of thousands of children and adolescents are living in poverty, working on the streets, and suffering from abuse and domestic violence (4). In the United States, around 1.2 million children suffer from abuse. These rates are much higher in LMICs, such as Brazil, where an estimated 28 million children suffer from maltreatment (2, 5, 6).

Evidence have shown that children and adolescent exposure to abuse and violence are associated with homelessness, reduced capacity for attachment, increased vulnerability to repeated victimization, suboptimal physical and brain development, and persistent cognitive impairment (7–11). Studies have reported that children exposed to maltreatment are at higher risk of behavioral problems, learning and communication disabilities, internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders, and general clinical conditions, such as obesity and systemic inflammation later in life (12, 13). In addition, a growing body of evidence points to the impact of maternal stress during pregnancy on neurodevelopmental disorders (14). Therefore, conditions during pregnancy and early-life can affect adult outcomes and health (15–18).

Conversely, evidence shows that adequate social support is an important protective factor against child maltreatment (19). Enrichment of early childhood environment interventions (e.g., before 5 years of age) for children born in disadvantaged families are associated with better adult social outcomes (e.g., attained higher levels of education, earned higher wages, reduced used of welfare system, and reduced likelihood to commit crime) (20, 21) and better adult health outcomes (fewer behavioral risk factors, such as tobacco, alcohol, and drug use, and better adult physical health) (18). In addition, late-life interventions during puberty (e.g., education) have also shown to promote schooling and improve mental (behavior) and physical health outcome among adults (22). Interestingly, the contribution of early-life factors (family and environment) accounted for at least half of adult health outcomes, independent of the education contribution (18). Early-life interventions through an integrated approach are potentially far more effective in promoting short- and long-term benefits and an overall well-being for the children (18).

In Brazil, community-based services have been established to serve children and adolescents with behavioral and mental problems. Referred to as “Centros de Atenção Psicosocial” or “CAPS” (in English, “Centers for Psychosocial Services”) (23), the program aim to integrate relevant governmental, non-governmental, and community stakeholders (such as advocacy groups and potential clients) to provide active and sustainable dialog, and guide effective interventions tailored to specific populations within a territory (24). However, in practice, the numbers of CAPS available to serve children and adolescents are not enough to address the need (25), and CAPS effectiveness has been limited due to divergent inter-agency agendas and rivalries, and coordination challenges.

To address this gap, a community-based global health program was developed to specifically serve traumatized and neglected children and adolescents in the city of São Paulo, The Equilibrium Program (“TEP”). The aim of this paper is to describe and discuss TEP’s implementation, highlighting its innovation aspects, the research projects developed within the program and its population profile. Finally, we will discuss TEP’s social impact, challenges, and limitations.

The Equilibrium Program

The Equilibrium Program is a community-based interdisciplinary intervention program that provides multi-dimensional bio-psycho-social treatment integrated with the diverse services needed to meet the unique demands of traumatized and neglected children and adolescents in the city of São Paulo.

The Equilibrium Program is a partnership between faculty at the Department and Institute of Psychiatry of the University of São Paulo Medical School (USP), services providers including health services, social, educational, justice services and child welfare agencies, and several São Paulo municipal departments. For instance, the Department of Health provides financial support for staffing and equipment; the Department of Sports provides physical space (e.g., the program is established inside a Municipal Sports Club), safety, and maintenance. Associated private initiatives have also been developed to support specific interventions, such as communication workshops, dog-assisted therapy, implementing computer systems, and speech therapy. Research funding was provided by grants from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), and the University of São Paulo Medical School Foundation (FFM).

The Equilibrium Program was created in response to a shortage of suitable public services available to address the various and broad needs of children and adolescent exposed and addicted to drugs and living on the streets of São Paulo. TEP expands and complements services provided by CAPS and Institutional Refuge Services for Children and Adolescents (Serviços de Acolhimento Institucional Para Crianças e Adolescentes, or “SAICA”), and incorporates innovative aspects, such as multidisciplinary perspectives, networking with health, education, social, and judicial services, all based at a municipal sports club facility.

The Equilibrium Program’s main goal is to provide socio-familiar reintegration for traumatized and neglected children and adolescents with behavioral and mental problems living in foster centers, such as group shelters, or under vulnerable conditions with their families. For children living with their families, the aim is to reinforce family relationships and to provide a safe family environment. Children and Youth Courts are responsible for analyzing and deciding if children are going to be reintegrated with their families or placed in foster and/or adoption centers. Although most children suffer abuse from their own parents, Brazilian law advocates that the family should receive support necessary to remedy the possible causes of domestic violence before placing children for adoption. However, given that most parents suffer from untreated psychiatric illness (26), the improvement of family living conditions and the promotion of parental psychiatric treatment are necessary steps before evaluating the parents’ capacity to properly care for their children. These interventions are provided through social service networks of judicial and child welfare agencies. TEP team supports this process by providing family therapy and reintegration workshops, and by orienting families toward available government benefits.

Group shelters operate under supervision and house about 20 children/adolescents in residences funded by non-governmental organizations and the city of São Paulo. Children and adolescents are referred to TEP by group shelter coordinators, children welfare agencies, and children and juvenile court agencies. More recently, schools and community centers within the vicinity also refer to the program children and adolescents living in vulnerable conditions. An average of 10 new participants is enrolled monthly in TEP.

The first step of the treatment is an initial diagnostic phase, a 4-week assessment performed by a multidisciplinary team (3). Whenever possible, family members are also involved to obtain additional information and participate in the development of a therapeutic plan.

During the diagnostic phase, clinical and psychiatric evaluations are performed to identify psychiatric or medical conditions. In addition, participants are evaluated by neuropsychologists, occupational therapists, art therapists, social workers, educational therapists, and speech therapists to address each participant’s unique problems and identify potential strengths. Psychiatric diagnoses are based on clinical interviews conducted by certified child and adolescent psychiatrists and discussed with a psychiatric coordinator (26).

After the initial assessment, an individualized and integrative therapeutic intervention plan is proposed, which includes periodic psychiatric and pediatric assessment, and individual or group interventions according to each participant’s needs, such as psychotherapy, art and speech therapy, school support, and recreational activities (such as theater, music, and athletics). All activities are integrated within the community center to create a flexible and accepting social environment (27).

A primary case manager is assigned for each participant to ensure coordination and continuity of care between the program activities and external agencies (such as group shelters, schools, and the children and juvenile court systems) and promote school, family, and social reintegration. Weekly treatment team meetings allow adjustments and modification of treatment plans to meet a participant’s evolving needs. Attention to the family’s needs, apart from those of the child or adolescent, is attempted whenever possible. The team thus works actively with other partner organizations to provide continuous care.

A participant’s engagement with the case manager is important to prevent dropouts. Case managers actively maintain contact, especially when participants are absent for more than 2 weeks. Assertive community outreach is often not possible because due to security concerns in some neighborhoods.

Initially, weekly appointments are scheduled. Depending upon a participant’s needs, appointment frequency may increase to three to four times a week, or may be reduced to monthly assessment as participants evolve and are integrated in other care services or programs.

Innovation

The development of TEP is based on a framework of community-based participatory research in which academic expert partner with community agencies, community stakeholders, and participants to provide assistance in the community programs (28). Development and implementation of TEP considered direct and indirect input from participants, community stakeholders, evidence-based data gathered during assessments and follow-up, as well as national and international service’s experiences and evidence-based practice (3, 23, 29–34). In addition, the program is tailored to the local cultural aspects of São Paulo, the most populous city in the Americas (35), which suffers from high levels urban crime, violence, and organized drug trade (3).

Another of TEP’s innovations is the offering of multidisciplinary services in a safe community setting: a municipal sports club in the vicinity of client residences, and accessible by relevant services (3, 26). The sports club is an attractive environment where children and adolescents are encouraged to participate in healthy activities and develop new abilities. Additionally, a local sports club setting promotes community reintegration and avoids stigmatization – something that often occurs with CAPS users.

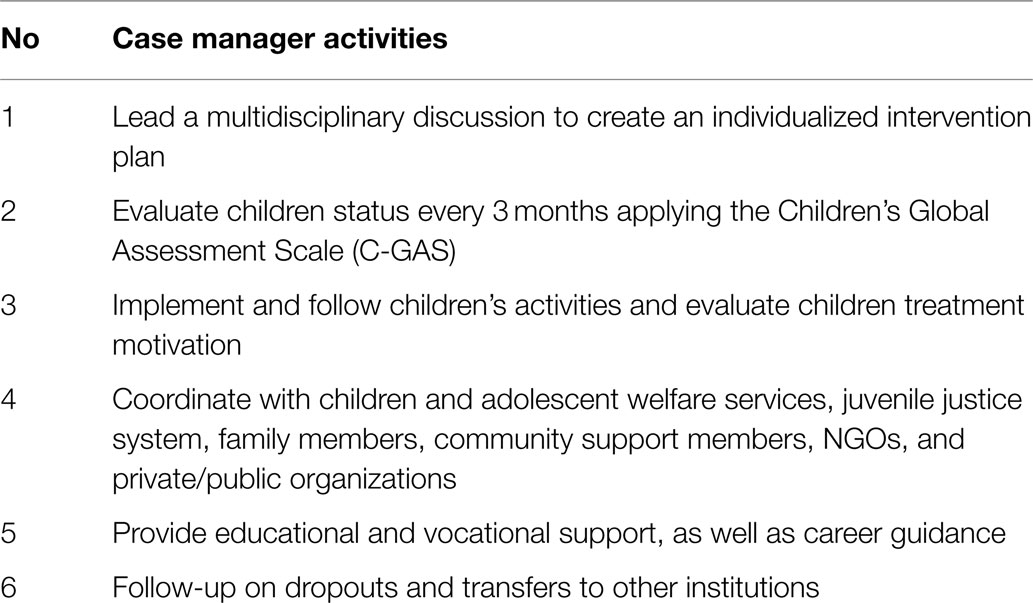

One more important innovation is that TEP has adopted a case management system to ensure continuity of care throughout the entire process of treatment and family reintegration. The main activities of the case manager are described in Table 1.

Another innovative aspect of TEP is the development of research projects to assess population profiles and to evaluate program efficacy. Information on service delivery and client data is systematically collected to improve interventions and support sustainable operations. These data will be essential to promote the program’s future expansion into other areas of Brazil.

Finally, TEP facilitates the development of additional research projects to evaluate the impact of early-life stress on children’s neurodevelopment.

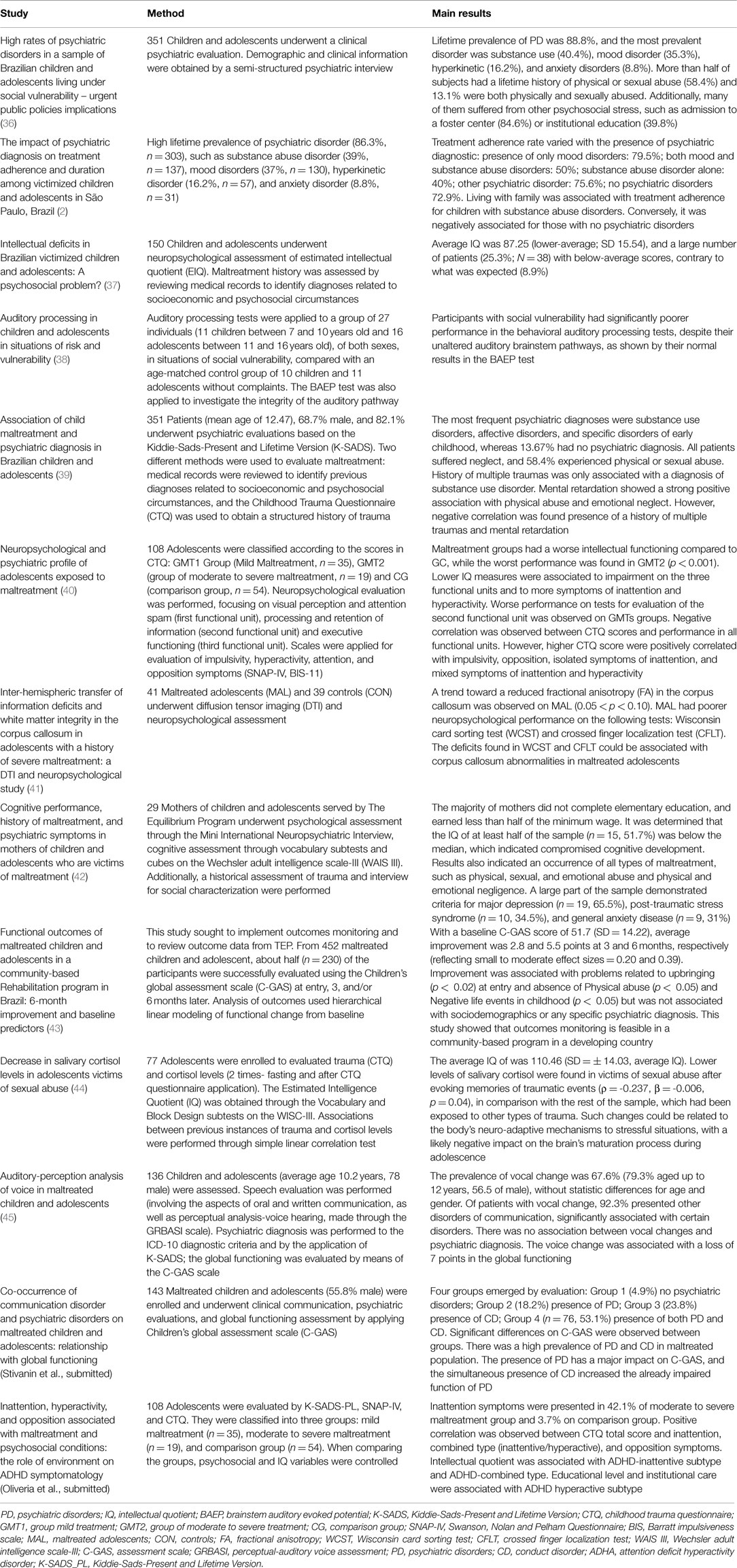

Table 2 describes all the research projects developed by TEP.

Population Profile

Studies of patients served by TEP have identified the prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses and an association with neuropsychological deficits, treatment adherence, and clinical evolution (Table 2). These studies demonstrated the feasibility of monitoring functional outcomes for TEP patients as an example of data monitoring for community-based programs for maltreated children in LMICs (3, 43).

In comparison with national epidemiological data (46), the lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorder were higher in this population [e.g., substance abuse disorder (39–31.9%), mood disorders (37–33.8%), hyperkinetic disorder (16.2–20.8%), conduct disorder (15.9%), anxiety disorder (11.7–8.8%), and developmental disorder (5.7%)] and have shown to impact treatment adherence (2, 39, 43) (see Table 2).

Treatment adherence was associated with slightly higher functioning (C-GAS Score β = 0.02, p < 0.01), and was less likely to have a history of physical abuse (β = 46, p < 0.03) (43). In another study, treatment adherence was better for those with only mood disorders (79.5%) than for those with substance abuse disorder (40%) or without any psychiatric disorders (72.9%) (2).

Most common social problems reported were negative life events, such as loss of a love relationship, removal from the home, experiencing an altered pattern of family relationships in childhood (95.3%); problems related to upbringing (84.1%), a family history of mental illness (57.5%), physical abuse (32.5%), sexual abuse (15.7%), and criminal involvement (11.5%) (43). These data emphasize the importance of global psychiatric assessment. Paying attention only to substance use disorders can lead to underestimation of other mental health problems (36). Therefore, continuous efforts are needed to improve psychiatric assessment, and distinct approaches, like dimensional and categorical measures, should be considered (47).

Improvement was observed after 3 and 6 months of follow-up (small to moderate effect sizes, 0.20 and 0.39) and was positively associated with problems related to upbringing, negatively associated with physical abuse and negative life events in childhood, and not associated with any socio-demographic characteristic or psychiatric diagnosis (43). However, some limitations have to be address, such as high rates of dropouts and lack of control group. Only half of the subjects had completed the treatment plan, which likely reflects the challenge of adherence in the program. Although there was a lack of a control group and no specific evidence-based treatments were applied, it is notable and encouraging that making services available from a multidisciplinary team in a safe supportive environment was associated with significant improvement within only 6 months period, albeit with a small to moderate effect size (43).

Other studies have also shown the impact of early life stress on children’s cognitive function, revealing a negative impact on intellectual functioning (43), poor neuropsychological performance associated with corpus callosum abnormalities (37, 48, 49), poor performance in behavioral auditory processing tests (38), deficit in auditory perception (48), and higher prevalence of communication disorder associated with psychiatric diagnosis (50) (Table 2).

Finally, another important data collected during the first year of the program is related to family’s member history. Child victims of abuse often lived in dysfunctional families, with a high frequency of untreated psychiatric problems (36). In addition, family members who reported involvement with alcohol and drugs also reported being abused as children and often did not receive any treatment (26). These findings corroborate with previous studies that report the association between children maltreatment and increased risk of substance use and other psychopathology in adulthood (51). These factors hinder the promotion of a healthy family environment. Therefore, successful family reintegration should address the cycle of unfavorable environment – psychic disintegration – violence, and promote parental mental and physical health (52).

Social Impact

The Equilibrium Program has demonstrated itself as a feasible program promoting important positive impacts on children and adolescents outcomes. Data collected from September 2007 through December 2014 are summarized below.

• 92,111 appointments

• Average of 1,046 appointments monthly

• 56.4% (344) clients on treatment or that completed the treatment plan (107–31.1% referred to other treatment centers)

• 47.1% (287) children/adolescents were reintegrated into families (original or step families)

• 42.8% (261) dropout

• 6.3% (39) released due to relocation with their families outside the city

• 0.65% (4) admitted into witness protection programs

• 0.16% (1) deaths

• 1,196 caregiver supervision sessions held from November 2011 to September 2013.

Challenges and Limitations

Challenges observed during TEP’s development and implementation provided relevant information to improve and expand similar efforts in Brazil and in other LMICs. Several challenges and limitations were observed along the 7 years of TEP’s activity.

First was the creation of a multidisciplinary service in a safe and non-stigmatized setting in the vicinity of user residences and safely accessible to providers. Second was the development and maintenance of the partnership between a university, other service providers (such as social services, school, health provider, and child welfare agencies) and the municipal government to address the needs of the population and to provide long-term financial support for the program. Another challenge was the monitoring of program outcomes. Although the program operates in a real-world setting, associated research projects are required to guide effective interventions, evaluate population profiles, and collect data to support of the development of public policies targeted to this specific population. This aspect was overcome by creating collaboration with national international academic experts, and pursuing grants from Brazilian funding agencies.

Another major challenge and limitation were the evaluation of TEP’s impact on the community. Although TEP could have potentially exerted a positive impact on the neighboring environment and decreased violence rates, these data were not collected due to lack of financial support. Finally, after few years of operation, the team learned that devoting attention and support to professionals working with children and adolescents, especially caregivers, is as important as addressing their needs. Therefore, providing support to reduce caregivers’ work stress, improving stability, and providing a suitable environment in group shelters is an essential strategy that can contribute to children’s outcome.

Conclusion

Children and adolescent maltreatment is a global public health problem affecting high-income and LMICs. Studies have shown that children exposed to maltreatment are at high risk of learning and communication disabilities, persistent cognitive impairment, behavioral problems, psychiatric disorders, and general clinical conditions, such as obesity and systemic inflammation later in life (13).

A better understanding of the multiple factors affecting mental health status of children and adolescents is necessary but not sufficient for the development of novel treatment approaches required to serve this population (53). Services models to treat traumatized children applied in developed countries, such as assertive community approaches, may not be compatible in deeply impoverished urban neighborhoods in LMICs due to the high levels of urban crime, violence, and the organized drug trade (30, 31).

In Brazil, services available to homeless children or in supervised group shelters are frequently inadequate, fragmented, and poorly coordinated (32). There is little interaction between social and health systems, social support is precarious, and health care follow-up is impeded by frequent changes of client residence and the impracticability of assertive community outreach due to a lack of safety for community workers (54). As a result, it is difficult to maintain the bonds that sustain the confidence and trust of children and adolescents in these situations. Long-term follow-up, from the street to the point of family reintegration, is essential to countering further family disaffection.

The Equilibrium Program was developed to fill this gap. TEP is an interdisciplinary intervention program that provides multi-dimensional bio-psycho-social treatment for multiply traumatized children and adolescents, integrating widely diverse services needed to meet the unique demands of this population (e.g., general health care assistance, schools, social services, child welfare programs, and the criminal justice system) in a safe, accessible setting. The program’s main goal is to promote social and family reintegration of maltreated children and adolescents. TEP was developed and implemented through a partnership between academic psychiatrists from the University of São Paulo Medical School, the São Paulo municipal government, and potential users. TEP innovative aspects are as follows: (a) program development was guided by principles emphasizing acceptability to consumers, flexibility in addressing diverse client needs, and placing a focus on high-risk sub-populations within a supportive environment; (b) TEP is located in a community sports center near to many of the shelters close to downtown São Paulo. The center is open to the local community, serving to facilitate the social reintegration and stigma reduction process among those children and their families in a safe and secure environment; (c) TEP offers comprehensive mental and physical health care along with social services, specialized services, and support for school attendance while participating in social and recreational activities with their peers; (d) TEP is also performing research projects to assess population profiles and program evaluation efficacy by monitoring program outcomes as it operates in real-world setting to guide effective interventions.

After 7 years of activity and based on research developed in a real-world setting to monitor program efficacy, data show that TEP is a feasible and sustainable program that helps to revert the inter-generational violence cycle through a multidisciplinary work in a non-stigmatized environment, which emphasizes building connections between users, staff, and all stakeholders.

Box 1. Key Features of TEP.

(1) Offers intensive professional services that are accessibly located within the community in a context primarily associated with recreational activities,

(2) Offers an environment far away from adverse environmental elements in the community,

(3) Is accessible to majority of service providers located elsewhere in the city, and

(4) Promotes active community and family reintegration of maltreated children and adolescents.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially funded by the University of São Paulo, Medical School Foundation (FFM), São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) and by São Paulo Municipality. We would like to thank CEAPESQ-IPq for the statistics support; FAPESP (Grants number 2010/18374-6 and 2011/19185-5 – Dr. Sandra Scivoletto), as well as the São Paulo City Hall, public schools, foster centers and justice system, that have been working together with The Equilibrium Project, and the University of São Paulo.

References

1. Runyan DK, Shankar V, Hassan F, Hunter WM, Jain D, Paula CS, et al. International variations in harsh child discipline. Pediatrics (2010) 126(3):e701–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2374

2. Scivoletto S, Silva TF, Cunha PJ, Rosenheck RA. The impact of psychiatric diagnosis on treatment adherence and duration among victimized children and adolescents in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo) (2012) 67(1):3–9. doi:10.6061/clinics/2012(01)02

3. Scivoletto S, de Medeiros Filho MV, Stefanovics E, Rosenheck RA. Global mental health reforms: challenges in developing a community-based program for maltreated children and adolescents in Brazil. Psychiatr Serv (2014) 65(2):138–40. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300439

4. UNICEF. Progress for Children New York 2009. Available from: http://www.childinfo.org/files/Progress_for_Children-No.8_EN.pdf

5. Bordin IAS, Paula CS, do Nascimento R, Duarte CS. Severe physical punishment and mental health problems in an economically disadvantaged population of children and adolescents. Rev Bras Psiquiatr (2006) 28(4):290–6. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462006000400008

6. Tucci AM, Kerr-Corrêa F, Souza-Formigoni ML. Childhood trauma in substance use disorder and depression: an analysis by gender among a Brazilian clinical sample. Child Abuse Negl (2010) 34:95–104. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.001

7. Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. Am J Psychiatry (2003) 160(8):1453–60. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453

8. Martinez RJ. Understanding runaway teenns. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs (2006) 19(2):77–88. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2006.00049.x

9. Thrane LE, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB, Yoder KA. Impact of family abuse on running away, deviance, and street victimization among homeless rural and urban youth. Child Abuse Negl (2006) 30(10):1117–28. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.008

10. Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Moylan CA. Intersection of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence. Trauma Violence Abuse (2008) 9(2):84–99. doi:10.1177/1524838008314797

11. Nguyen HT, Dunne MP, Le AV. Multiple types of child maltreatment and adolescent mental health in Viet Nam. Bull World Health Organ (2010) 88:22–30. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.060061

12. Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Wood PA, Aarons GA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2001) 40(4):409–18. doi:10.1097/00004583-200104000-00009

13. Moylan CA, Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Russo MJ. The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. J Fam Violence (2010) 25(1):53–63. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9

14. Marques AH, Bjorke-Monsen AL, Teixeira AL, Silverman MN. Maternal stress, nutrition and physical activity: impact on immune function, CNS development and psychopathology. Brain Res (2015) 1617:28–46. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.051

15. Conti G, Heckman JJ. Understanding the early origins of the education-health gradient: a framework that can also be applied to analyze gene-environment interactions. Perspect Psychol Sci (2010) 5(5):585–605. doi:10.1177/1745691610383502

16. Almlund M, Duckworth A, Heckman JJ, Kautz T. Personality psychology and economics. In: Hanushek EA, Machin S, Wößmann L, editors. Handbook of the Economics of Education. Vol. 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2011). p. 1–181. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53444-6.00001-8

17. Almond D, Currie J. Human capital development before age five. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D, editors. Handbook of Labor Economics. Vol. 4B. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2011). p. 1315–486. doi:10.1016/S0169-7218(11)02413-0

18. Conti G, Heckman JJ. The developmental approach to child and adult health. Pediatrics (2013) 131(Suppl 2):S133–41. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0252d

19. Lane WG. Prevention of child maltreatment. Pediatr Clin North Am (2014) 61(5):873–88. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2014.06.002

20. Sparling J, Lewis I. Learning Games for the First Three Years: A Guide to Parent/Child Play. New York, NY: Berkley Books (1979).

21. Sarling J, Lewis I. Learning Games for Three and Fours. New York, NY: Walker and Company (1984).

22. Conti G, Heckman J, Urzua S. The education-health gradient. Am Econ Rev (2010) 100(2):234–8. doi:10.1257/aer.100.2.234

23. Caldas de Almeida JM, Horvitz-Lennon M. Mental health care reforms in Latin America: an overview of mental health care reforms in Latin America and the Caribbean. Psychiatr Serv (2010) 61(3):218–21. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.61.3.218

24. Lauridsen-Ribeiro E, Tanak O. Atenção em saúde mental para crianças e adolescentes no SUS. São Paulo: Hucitec (2010).

25. Psiquiatria ABD. Pesquisa sobre sintomas de transtornos mentais e utilização de serviços em crianças brasileiras (2010). Available from: http://www.abp.org.br/portal/imprensa/pesquisa-abp/

26. Scivoletto S, da Silva TF, Rosenheck RA. Child psychiatry takes to the streets: a developmental partnership between a university institute and children and adolescents from the streets of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Child Abuse Negl (2011) 35(2):89–95. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.11.003

27. Ungar M. Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma Violence Abuse (2013) 14(3):255–66. doi:10.1177/1524838013487805

28. Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2003).

29. Shipman K, Taussig H. Mental health treatment of child abuse and neglect: the promise of evidence-based practice. Pediatr Clin North Am (2009) 56(2):417–28. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.02.002

30. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Factors that mediate treatment outcome of sexually abused preschool children: six- and 12-month follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (1998) 37:44–51. doi:10.1097/00004583-199801000-00016

31. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Predictors of treatment outcome in sexually abused children. Child Abuse Negl (2000) 24:983–94. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00153-8

32. Pumariega AJ, Winters NC. The Handbook of Child and Adolescent Systems of Care: The New Community Psychiatry. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2003).

33. Chaffin M, Friedrich W. Evidence-based treatments in child abuse and neglect. Child Youth Serv Rev (2004) 26(1097):1097–113. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.08.008

34. Darbyshire P, Muir-Cochrane E, Fereday J, Jureidini J, Drummond A. Engagement with health and social care services: perceptions of homeless young people with mental health problems. Health Soc Care Community (2006) 14(6):553–62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00643.x

35. SP W. Sao Paulo (2015). Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sao_paulo

36. Silva TF, Cunha PJ, Scivoletto S. High rates of psychiatric disorders in a sample of Brazilian children and adolescents living under social vulnerability – urgent public policies implications. Rev Bras Psiquiatr (2010) 32(2):195–6. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462010000200018

37. Oliveira PA, Scarpari GK, Dos Santos B, Scivoletto S. Intellectual deficits in Brazilian victimized children and adolescents: a psychosocial problem? Child Abuse Negl (2012) 36(7–8):608–10. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.002

38. Murphy CF, Pontes F, Stivanin L, Picoli E, Schochat E. Auditory processing in children and adolescents in situations of risk and vulnerability. Sao Paulo Med J (2012) 130(3):151–8. doi:10.1590/S1516-31802012000300004

39. Scomparini LB, Santos B, Rosenheck RA, Scivoletto S. Association of child maltreatment and psychiatric diagnosis in Brazilian children and adolescents. Clinics (Sao Paulo) (2013) 68(8):1096–102. doi:10.6061/clinics/2013(08)06

40. Oliveira AP. Perfil neuropsicológico e psiquiátrico de adolescentes submetidos a maus tratos. Sao Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo (2013).

41. Cunha PJ, Ometto M, Oliveira PA, Milioni ALV, Scarpari GK, Pereira F, et al. Interhemispheric transfer of information deficits and white matter integrity in the corpus callosum in adolescents with a history of severe maltreatment: a DTI and neuropsychological study. 8 Meeting Central Nervous System Investigation: RNA Metabolism in Neuroliogic Disease. San Diego, CA (2013).

42. Silva AC, Oliveira PA, Costa CF, Sousa A, Scivoletto S. Funcionamento cognitivo, histórico de maus tratos e sintomas psiquiátricos em mães de crianças e adolescentes vítimas de maus tratos. Apresentação de Trabalho/Congresso. Sao Paulo: Elsevier – Child Abuse & Neglect (2013).

43. Stefanovics EA, Filho MV, Rosenheck RA, Scivoletto S. Functional outcomes of maltreated children and adolescents in a community-based rehabilitation program in Brazil: six-month improvement and baseline predictors. Child Abuse Negl (2014) 38(7):1231–7. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.025

44. Oliveria PA, Silva AC, Costa CF, Cunha PJ, Santos B, Scivoletto S. Diminuição de níveis de cortisol salivar em adolescentes vítimas de abuso sexual. 10 congresso brasileiro de cérebro. Gramado (2014).

45. Stivanin L, dos Santos FP, de Oliveira CC, dos Santos B, Ribeiro ST, Scivoletto S. Auditory-perceptual analysis of voice in abused children and adolescents. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol (2015) 81(1):71–8. doi:10.1016/j.bjorl.2014.11.006

46. Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Goodman R. Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in southeast Brazil. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2004) 43(6):727–34. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000120021.14101.ca

47. Rutter M. Categories, dimensions, and the mental health of children and adolescents. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2003) 1008:11–21. doi:10.1196/annals.1301.002

48. Oliveira PA, Pontes F, Stivanin L, Scivoletto S. Prevalence of hearing loss in victimized children and adolescents with psychiatric diagnoses: pilot study. The Jerusalem International Conference Neuroplasticity and cognitive modifiability. Jerusalem (2013).

49. Oliveira AP, Moreira CF, Scivoletto S, Rocca CCA, Fuentes D, Cunha PJ. Intellectual disability and psychiatric diagnoses of children and adolescents with a history of stressful events and social deprivation in Brazil: preliminary results. IQ, depression and stress. J Intellect Disabil Diagn Treat (2014) 2:42–5. doi:10.6000/2292-2598.2014.02.01.5

50. Picoli E, Stivanin L, Pontes F, Oliveira CCC, Schochat E, Scivoletto S. Auditory Processing in Children and Adolescents Living Under Social Vulnerability. Sao Paulo: Scientific Journal of Hospital das Clinicas FMUSP (2010). S174 p.

51. Smith DW, Davis JL, Fricker-Elhai AE. How does trauma beget trauma cognitions about risk in women with abuse historie. Child Maltreat (2004) 3:292–303. doi:10.1177/1077559504266524

52. Stover CS. Domestic violence research: what have we learned and where do we go from here? J Interpers Violence (2005) 20(4):448–54. doi:10.1177/0886260504267755

53. Eisenberg L, Belfer M. Prerequisites for global child and adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry (2009) 50(1–2):26–35. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01984.x

Keywords: traumatized children and adolescents, child neglect, child maltreatment, child abuse, homeless children, mental health, integrated care

Citation: Marques AH, Oliveira PA, Scomparini LB, Silva UMRe, Silva AC, Doretto V, Medeiros Filho MV and Scivoletto S (2015) Community-based global health program for maltreated children and adolescents in Brazil: the equilibrium program. Front. Psychiatry 6:102. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00102

Received: 30 March 2015; Accepted: 01 July 2015;

Published: 30 July 2015

Edited by:

Julio Eduardo Armijo, Universidad de Santiago, ChileReviewed by:

Meera Balasubramaniam, NYU Langone Medical Center, USAYasser Khazaal, Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland

Copyright: © 2015 Marques, Oliveira, Scomparini, Silva, Silva, Doretto, Medeiros Filho and Scivoletto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Horvath Marques, Rua Dr. Ovidio Pires de Campos 785, São Paulo, SP 05403-903, Brazil,YW5kcmVhaG9ydmF0aG1hcnF1ZXNAZ21haWwuY29t

Andrea Horvath Marques

Andrea Horvath Marques Paula Approbato Oliveira

Paula Approbato Oliveira Luciana Burim Scomparini

Luciana Burim Scomparini Uiara Maria Rêgo e Silva

Uiara Maria Rêgo e Silva Angelica Cristine Silva

Angelica Cristine Silva Victoria Doretto

Victoria Doretto Mauro Victor de Medeiros Filho

Mauro Victor de Medeiros Filho Sandra Scivoletto

Sandra Scivoletto