94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Psychiatry , 14 March 2013

Sec. Molecular Psychiatry

Volume 4 - 2013 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00013

Talking about non-continuous antipsychotic treatment in psychiatric practice in our time is tantamount to heresy. We have been perseverating in comparing psychiatric illness to diabetes and hypertension so much that we are having a hard time fathoming a different analogy; perhaps, lupus, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, or cancer in which intermittent dosing for shorter period of time is acceptable.

In 1960s and 1970s, there was a lot of talk about targeting intermittent treatment throughout the duration of illness, rather than chronic and final phase of schizophrenia. Widespread use of antipsychotics is historically novel that only a small percentage phase four patients are being seen currently by average psychiatrists, but this number may grow in time. Reviewing the psychiatric literature from 1970s, it appears that continuous antipsychotic exposure were not always necessary at that time (Prien et al., 1973).

Even in our times there are advocates of non-continuous treatment after the first episode of schizophrenia, as about 50% of patients have remained stable after discontinuing medications in the second year of treatment (Harrow and Jobe, 2007). Also, the duration of antipsychotic treatment after a first episode of psychosis remains unclear. A comparison of evidence-based treatment guidelines from different countries developed on highest-quality criteria, yielded inconsistent recommendations regarding the duration of maintenance treatment (Gaebel et al., 2011).

Reviewing the current body of evidence, it appears that though the efficacy of antipsychotics in general is proven, a significant proportion of patients suffer from partial remission, symptom recurrence, or relapse, despite continuous antipsychotic treatment. This also applies to depot neuroleptic treatment, which minimizes adherence problems.

Several studies suggest that with careful clinical observation, substantial reduction of maintenance doses can, for many patients, lead to improvement in some areas of subjective and objective well-being and to a diminution of adverse effects (Kane et al., 1986).

Schizophrenic patients remain on antipsychotic (i.e., antidopaminergic) treatment for years, yet remarkably little is known about what happens to the dopamine function during ongoing treatment (Remington and Kapur, 2010). What is known is that in late stages of schizophrenia, antipsychotics become inefficient frequently, despite chronic continuous treatment.

There is evidence from preclinical as well as clinical studies that point to the build up of dopamine supersensitivity (Samaha et al., 2007) and tolerance to antipsychotics, leading to treatment failure over time.

Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis (Chouinard et al., 1978; Chouinard and Jones, 1980) has been observed after withdrawal from antipsychotic drugs such as quetiapine (Margolese et al., 2002), clozapine (Ekblom et al., 1984; Tollefson et al., 1999), olanzapine (Llorca et al., 2001), haloperidol (Kahne, 1989), and fluphenazine enanthate (Chouinard and Jones, 1980).

Clinical data are available to suggest antipsychotic tolerance with continuous treatment (Stip et al., 1995). The late or chronic stages of schizophrenia are associated with higher antipsychotic doses and diminished clinical response, also suggesting tolerance (Remington et al., 1997; Yamin and Vaddadi, 2010).

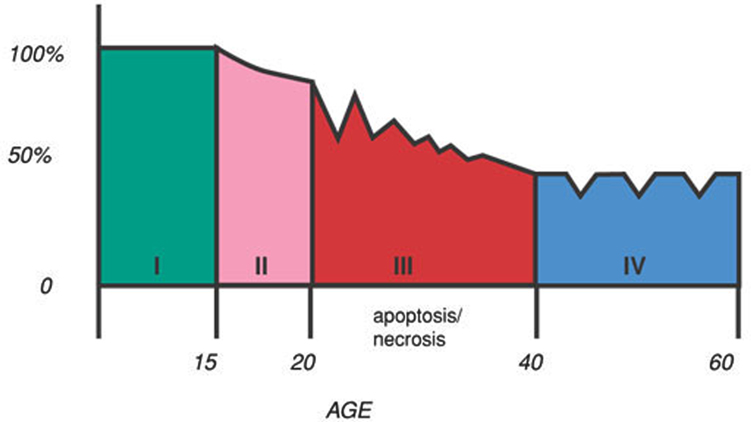

Is it possible that in chronic “burn out” phase of schizophrenia (Figure 1) in which there is neuronal and synaptic loss, a targeted or intermittent antipsychotic treatment is more beneficial to the patient? In dementia, where there is extensive cerebral tissue loss, antipsychotics are being used only intermittently and for a shorter duration of time.

Figure 1. Stages of schizophrenia. Stage 1. The patient is fully functional in early part of life, and is virtually asymptomatic. Stage 2. Prodromal phase starts in teens. There may be odd behaviors and subtle negative symptoms. Stage 3. The acute phase of the illness occurs in twenties or thirties, with positive and negative symptoms. Stage 4. “Burn out” phase occurs in forties or fifties with prominent negative and cognitive symptoms.

Just wondering if schizophrenic patients in late phases would benefit from a similar strategy. At this time, therapy using “as needed” antipsychotic medications is being discouraged in favor of continuous treatment, yet quite the opposite might be needed in this stage.

Recent data including animal studies, suggests that long-term antipsychotic treatment leads to global brain volume reduction (Ho et al., 2011).

In medicine, we are aware of many instances where target symptom improves by worsening other symptoms. Hormone therapy relieves menopausal symptoms but increases stroke risk. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs relieve pain, but increase the likelihood of duodenal ulcers and gastrointestinal tract bleeding. It is possible that although antipsychotics relieve psychosis and its attendant suffering, these drugs may not arrest the pathophysiologic processes underlying schizophrenia, and may even aggravate progressive brain tissue volume reductions (Ho et al., 2011).

The last phase of schizophrenia or the “burn out” phase, like dementia, is characterized by extensive neuronal and synaptic loss. Since both chronic schizophrenia and prolonged antipsychotic treatment result in cerebral tissue loss, it is appropriate to revisit intermittent, targeted, or “as needed” use of antipsychotics at this stage.

I would like to thank Dr. Stahl for providing the figure “Stages of Schizophrenia.”

Chouinard, G., and Jones, B. D. (1980). Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis: clinical and pharmacologic characteristics. Am. J. Psychiatry 137, 16–21.

Chouinard, G., Jones, B. D., and Annable, L. (1978). Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 135, 1409–1410.

Ekblom, B., Eriksson, K., and Lindstrom, L. H. (1984). Supersensitivity psychosis in schizophrenic patients after sudden clozapine withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 83, 293–294.

Gaebel, W., Riesbeck, M., and Wobrock, T. (2011). Schizophrenia guidelines across the world: a selective review and comparison. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 23, 379–387.

Harrow, M., and Jobe, T. H. (2007). Factors involved in outcome and recovery in schizophrenia patients not on antipsychotic medications: a 15-year multifollow-up study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 195, 406–414.

Ho, B. C., Andreasen, N. C., Ziebell, S., Pierson, R., and Magnotta, V. (2011). Long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volumes: a longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 128–137.

Kahne, G. J. (1989). Rebound psychoses following the discontinuation of a high potency neuroleptic. Can. J. Psychiatry 34, 227–229.

Kane, J. M., Woerner, M., and Sarantakos, S. (1986). Depot neuroleptics: a comparative review of standard, intermediate, and low-dose regimens. J. Clin. Psychiatry 47(Suppl.), 30–33.

Llorca, P. M., Vaiva, G., and Lancon, C. (2001). Supersensitivity psychosis in patients with schizophrenia after sudden olanzapine withdrawal. Can. J. Psychiatry 46, 87–88.

Margolese, H. C., Chouinard, G., Beauclair, L., and Belanger, M. C. (2002). Therapeutic tolerance and rebound psychosis during quetiapine maintenance monotherapy in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 22, 347–352.

Prien, R. F., Gillis, R. D., and Caffey, E. M. (1973). Intermittent pharmacotherapy in chronic schizophrenia. Hosp. Community Psychiatry 24, 317–322.

Remington, G., and Kapur, S. (2010). Antipsychotic dosing: how much but also how often? Schizophr. Bull. 36, 900–903.

Remington, G. J., Prendergast, P., and Bezchlibnyk-Butler, K. Z. (1997). Neuroleptic dosing in chronic schizophrenia: a 10-year follow-up. Can. J. Psychiatry 42, 53–57.

Samaha, A., Seeman, P., Stewart, J., Rajabi, H., and Kapur, S. (2007). Breakthrough dopamine supersensitivity during ongoing antipsychotic treatment leads to treatment failure over time. J. Neurosci. 27, 2979–2986.

Stip, E., Tourjman, V., Lew, V., Fabian, J., Cormier, H., Landry, P., et al. (1995). “Awakenings” effect with risperidone. Am. J. Psychiatry 152, 1833.

Tollefson, G. D., Dellva, M. A., Mattler, C. A., Kane, J. M., Wirshing, D. A., and Kinon, B. J. (1999). Controlled, double-blind investigation of the clozapine discontinuation symptoms with conversion to either olanzapine or placebo. The Collaborative Crossover Study Group. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 19, 435–443.

Citation: Sfera A (2013) Targeted intermittent treatment in chronic schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 4:13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00013

Received: 29 September 2012; Accepted: 25 February 2013;

Published online: 14 March 2013.

Edited by:

Trevor R. Norman, University of Melbourne, AustraliaReviewed by:

Trevor R. Norman, University of Melbourne, AustraliaCopyright: © 2013 Sfera. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence:ZHIuc2ZlcmFAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.