- Department of Security Studies, Faculty of Applied Sciences, WSB University, Dąbrowa Górnicza, Poland

Much research confirms that the country of origin of migrants (refugees), as well as their religion, determines the approach of the destination country society to newcomers. It affects the conditions of receiving the acceptance of a legal stay and possible support. Double standards are the main results of this intersection. The study aimed to present the research results on the securitization processes implemented in Poland as a response to two migration crises related to the influx of migrants and refugees from MENA countries and Ukraine. Proposed by Rita Floyd, a just and unjust securitization approach has been implemented in the analysis of securitization movements undertaken by Polish governments in 2015–2023. Critical discourse analysis (CDA) has been used to analyze securitization done by politicians in response to expectations of the society. The results confirm that although in the case of both described influx of securitization of migrants has been implemented, not in all cases it was a response to an existential threat. Migration from MENA countries was securitized much more often than from Ukraine and, at the same time, in most cases, it was unjust securitization. Those results confirm that the country of origin determines the securitization process as well as their justification.

1 Introduction

Migration–security nexus appeared in security studies in the 1990s. Still, they exploded as a research topic in the XXI century, especially after 9/11 and the changes caused by this terrorist attack in American immigration policy (Weiner and Stanton Russell, 2001; Bigo, 2002; Goldstone, 2002; Guild and van Selm, 2005; Adamson, 2006; Huysmans, 2006; Bourbeau, 2011; Sciubba, 2011; Urdal, 2005; Black et al., 2011; Goldstone et al., 2012; Rodrigues, 2015). The refugee crisis in Europe in 2015, the border crisis from 2021 on the eastern external border of the EU caused by the Belarusian regime, and finally, the war in Ukraine and an influx of war refugees (2022) made the topic more and more important for research and practice. Increasing migration flows are recognized, together with the continuous population aging, as a significant challenge for the future of demographic trends in the European Union (EU). Security perspective is implemented in the analysis of phenomena more and more often, contrary to Huysmans’s expectations of desecuritization (Huysmans, 2006) or Dimari’s proposal of flexicuritization, as the approach that meets contradictory needs and expectations of two migrant actors—receiving countries (and their societies), as well as migrants themselves (Dimari, 2022).

International migration has been a convenient reference point for unspecific fears for 30 years. The depiction of international migration as a security threat in the West has unwillingly contributed to what Samuel Huntington has termed the “clash of civilizations” (Huntington, 1991). Securitizing migration reinforces the stereotypes about cultural fears and clashes that politicians publicly deny and abstain (Faist, 2005, 5–6).

According to the literature review, three formations of the migration–security nexus can be indicated. First, the most popular, introduced by International Relations, refers to the perception of migration as an insecurity provider. According to Lohrmann (2000, 4), movements of persons across borders affect security by shaping national security agendas of receiving and transit countries that perceive massive international population movement as a threat to their economic wellbeing, social order, cultural and religious values, and political stability. If immigrants are not integrated into host communities, mainly if they come from a different cultural environment, the potential risk of religious and ethnic conflicts tends to be higher, demanding new governmental integration efforts of ethnic minorities into national communities (Savage, 2004).

In this case, the securitization of migration tends to include four different axes: socioeconomic, due to unemployment, the rise of the informal economy, welfare state crisis, and urban environment deterioration; securitarian, considering the loss of a control narrative that associates sovereignty, borders, and both internal and external security; identitarian, where migrants are considered as being a threat to the host societies’ national identity and demographic equilibrium; and political, as a result of anti-immigrant, racist, and xenophobic discourses (Ceyhan and Tsoukala, 2002, 24).

At the same time, migrations might affect relations between states, as movements tend to create tensions and burden bilateral relations. By implicating individual security and dignity of migrants and refugees, irregular migration flows and involuntary population displacements may render migrants into unpredictable actors (Lohrmann, 2000, 5). Finally, migrations might affect the national security of the country of origin of migrants by weakening its resources. Migrations also matter when migrants or refugees are opposed to their home countries’ regime when they are perceived as a security risk or a cultural threat in the home country or when the host state or society uses immigrants as an instrument against the country of origin (Estevens, 2018, 4; Weiner, 1992, 105–106; Polko, 2024).

Proposed by G. Dimari “flexicuritization” as a pragmatic, utilitarian, flexible, and positive form of desecuritization of migration which constitutes a feasible and implementable solution in the Greek case might be the practical solution for the clash between needs and expectations of receiving societies and migrants themselves.

The second understanding of the migration–security nexus was introduced by UNPTD with the human security approach. Here, migration is perceived as a referent object under threat (Lewis, 2003; UNDP 1994). The human security approach focuses attention on the security of the individual during the process of migrating and while staying in the country of destination (illegal work, work exploitation, involvement in prostitution, and human organ trafficking networks; Burgess, 2011, 15; Geddes, 2003, 22; Czaika and de Haas, 2013). It shifts away from the state as the subject of security and brings into view the security of humans who migrate. It is widely presented in the research and practice on refugees and asylum seekers (Nadig, 2002), as well as in the trafficking of (primarily women and children) migrants (Clark, 2003). The risk of losing identity and relations with the country of origin is as important as the risk of living outside the law, in poverty, or physical threats to human beings.

The third approach tends to see migration as a security resource. For the destination country, migration often matters as a source of support for the labor market in the era of the demographic gap. More and more countries change internal laws and introduce immigrants to their national security systems by recruiting to the army or other special entities. For migrants themselves, especially refugees, when movement is a response to dangers in their country of origin, migration means security.

The country of origin of migrants and their religion are indicated as crucial factors determining their perception in the receiving countries responsible for acceptance (or not) and securitization processes. The danger of fallen integration is perceived as the key trigger to anti-immigrant discourse and practice, based on society’s fears and prejudices. It drives migration policies based on reducing the number of newcomers and limiting humanitarian help provided by the country of destination. However, literature on the relationship between migration and integration does not give one answer to the question about the role of culture and religion in integration with the receiving country’s society (Sarli and Mezzetti, 2020, 433; Alba and Foner, 2015; Kivisto, 2014; Lewis and Kashyap, 2013; García-Muñoz and Neuman, 2012; Zolberg and Woon, 1999). The North American literature tends to see religion as a factor fostering integration, by playing a role in addressing migrants’ social needs. Religious identity and participation in public religious life are thought to facilitate the Americanization of recent migrants and their descendants, strengthen their sense of belonging vis-à-vis the host country, and increase the level of acceptance of minorities by the dominant group (Foner and Alba, 2008). On the contrary, in Europe, literature sees migrants’ religion as a problem and a potential source of conflict, in line with a social attitude widespread across the continent. In particular, the relationship between religion and integration tends to be framed in a negative way as religious affiliation, especially with Islam, is considered to be a marker of wide social distance and a factor of disadvantage in the interaction with the native population (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Qasmiyeh, 2010). It results in strong securitization of the migration of Muslims to European countries.

As Khader noted, in the 1980s, migrants started to be perceived not as immigrants from Morocco, Pakistan, or Turkey but as “Muslims,” eventually threatening the social fabric of European societies. The terrorist attacks by tiny groups of Islamist fanatics and the radicalization of thousands of native Muslim Europeans added fuel to the surging anti-Muslim sentiment in Europe (Khader, 2015). During the last two decades of rising antimigrant racism in Europe, Islamophobia has proven to be the highest, most acute, and widely spread form of racism (Perocco, 2018). Public opinion surveys in Europe show increasing fear of European Muslims, who are perceived as a threat to national identity, domestic security, and social welfare even if a review of the empirical literature on the migration–terrorism nexus indicates that there is little evidence that more migration unconditionally leads to more terrorist activity (Helbling and Meierrieks, 2022). In Poland, 43% of Poles have negative emotions toward migrants from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East: 27% of respondents feel anxiety; 11% feel fear; and 5% feel anger. In turn, 34% of Poles have a positive attitude toward migrants. Every fifth respondent indicated indifference (Ipsos, 2023). These opinions do not correspond with the number of immigrants in Poland: from approximately 3.5 million immigrants in Poland, 60–75% are Ukrainians. The second place is occupied by Belarusians. On the next positions are Moldovans, Georgians, Russians, Indians, Germans, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Turks (GUS, 2023).

2 Materials and methods

As the Cold War ended, the debate about security and its understanding started. The traditional approach presenting the state’s security through the political and military perspective was too “narrow” for new kinds of threats generated by global factors such as the condition of the environment, economic crises, or pandemics, which have become more and more important for the citizens. Dissatisfied with the traditional responses to dangers, wideners sought to include other types of threats that were not military in nature and that affected people rather than states. One of the most critical groups introducing new concepts to International Relations was a group of scholars from the University of Copenhagen—Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jeep de Wilde (Copenhagen School)—who proposed the extension of the understanding of security known as The securitization theory.

The securitization theory shows the rhetorical structure of decision-makers when framing an issue and attempting to convince an audience to lift the issue above politics. This is what is called a speech act—‘by saying the words, something is done, like betting, giving a promise, naming a ship’ (Buzan et al., 1998, 26). Conceptualizing securitization as a speech act is important as it shows that words do not merely describe reality, but constitute reality, which, in turn, triggers specific responses. An issue becomes securitized when an audience collectively agrees on the nature of the threat and supports taking extraordinary measures. If the audience rejects the securitizing actor’s speech act, it only represents a securitization move and the securitization has failed. In this respect, focusing on the audience and the process requires considerably more than simply ‘saying security’. When securitization is accepted by the audience, extraordinary measures to combat the threat might be implemented. This approach has generated criticism from some scholars, who recommend understanding securitization as a long process of ongoing social constructions and negotiation between various audiences and speakers (Eroukhmanoff, 2018, 2). Otherwise, oversecuritization might appear and the use of extraordinary measures might be applied without justification (Polko, 2022a).

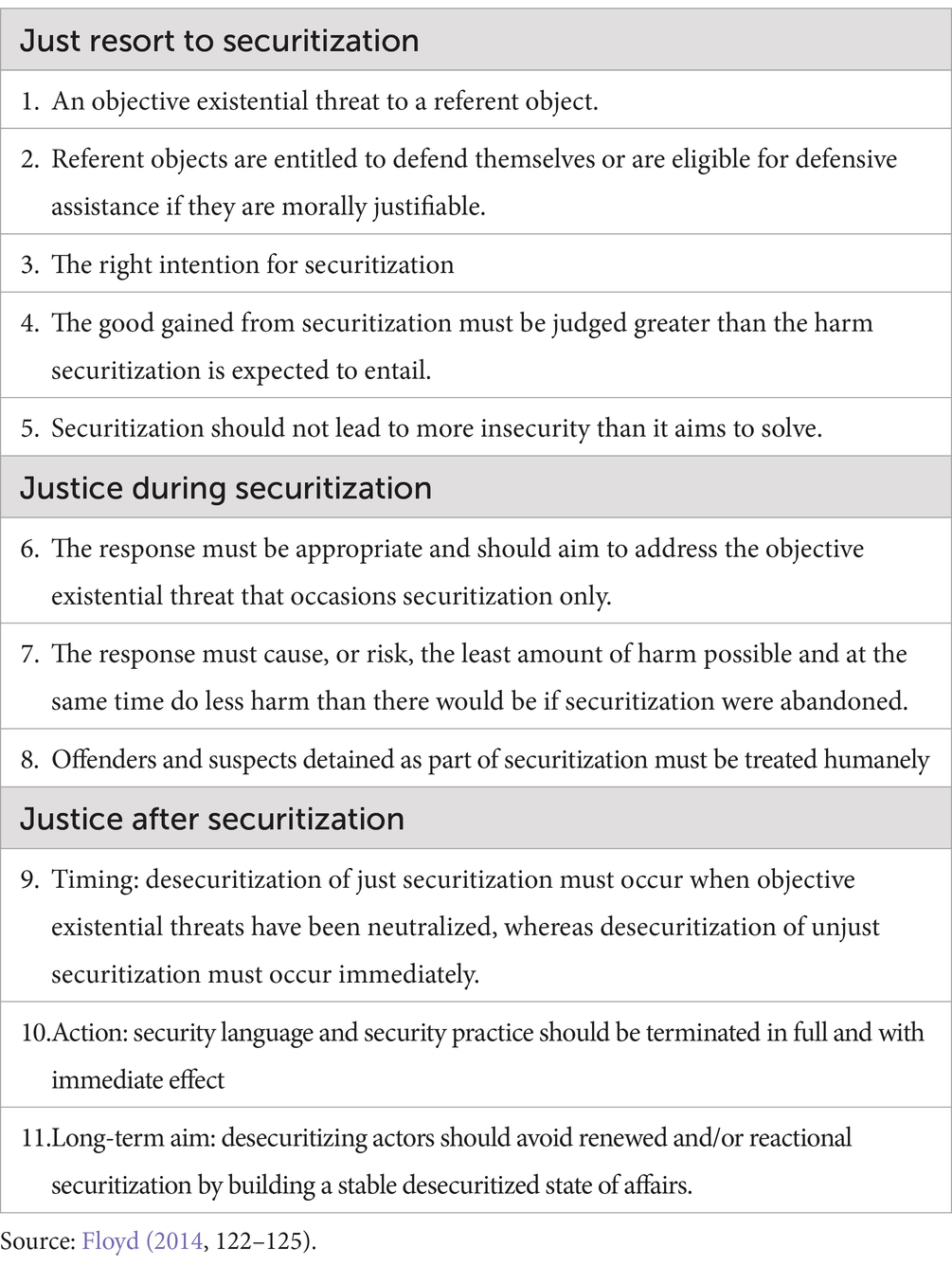

One of the more interesting critiques of the securitization theory is the study by (Floyd, 2007, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2016a,b, 2019), who not only pointed out the gaps in classical securitization theory but also proposed her normative approach, which resulted in just securitization theory (JST). The main differences with the theory proposed by the Copenhagen School concern first of all the existential threat itself, which, according to Floyd, should be objective (recognized as such, due to studies of the intentions and power of potential aggressors) Floyd refers to the observations of another of Buzan’s critics—T. Balzacq—who noted that while it is difficult to identify objective security threats, objective existential threats can already be successfully enumerated (Balzacq, 2005). Second, according to Floyd, it does not matter whether the recipients of the speech act—the audience (Floyd, 2016a)—accept it or not (which for the Copenhagen School was crucial) as the essence is action, i.e., the practice of security, implementation of specific policies, and not merely the acceptance of their description (Floyd, 2010). Figuratively, this can be represented by the equation:

where the securitization movement should be understood as a justification for an existential threat.

According to Floyd, securitization occurs not “when the audience accepts the justification of the existential threat, but when instead there is a change in behavior by the subject, which is justified by that subject using a reference to the declared threat. Securitization becomes successful by the fact that it has occurred, without the need to break normally applicable rules or introduce extraordinary measures” (Floyd, 2016b). Securitization is successful only if the identification of the threat justifying the securitization move is followed by a change in behavior (action) by the securitizing actor (or someone else at his behest) and if the action taken is justified by the securitizing actor’s reference to the threat identified and declared in the securitization movement. The ultimate object of reference is the human being, and security is not so much (not only) survival as it is the possibility of development (wellbeing).

Finally, according to Floyd, it is not even necessary to use extraordinary measures in dealing with securitized issues. The “standard emergency measures” enshrined in the constitutions of liberal democracies are sufficient, that is: introducing new laws under existing procedures; introducing new powers to manage the emergency, within the framework of the existing legal order, approved by the relevant courts or, finally, using the existing security apparatus and existing emergency legislation to resolve issues not previously addressed. Floyd’s proposed catalog of conditions for just securitization is presented in Table 1.

The theoretical framework proposed by Floyd has been implemented in the analysis of the Polish political discourse on migration to evaluate securitization of it. As material to analyze, selected parliamentary debates on migration have been used:

16 September 2015. Information of the Prime Minister on the migration crisis in Europe and its repercussions for Poland (with discussion);

15 June 2023. Report of the Committee on Foreign Affairs on the parliamentary draft resolution on the proposal to introduce an EU relocation mechanism for illegal migrants (with discussion);

Year 2022. 11 discussions and debates related to the presentation of The bill on assistance to citizens of Ukraine in connection with the armed conflict on the territory of this country and its changes (with discussion) (08.03.2022; 09.03.2022; 23.03.2022; 06.04.2022; 07.04.2022; 27.04.2022; 11.05.2022; 26.05.2022; 08.06.2022; 13.12.2022; 14.12.2022).

Those debates were chosen for the analysis as the most representative ones of the migration discourse in Poland. They present the spectrum of opinions presented by the most important Polish political parties in the XXI century. The Polish political scene was established in the first decade of the XXI century when the bipolar dichotomy of post-communist and post-solidarity (anticommunist) parties collapsed. New parties, although represented by old politicians, refer to all left–right axes. Two post-solidarity parties dominate the political scene and have ruled Poland alternately since 2005: Right-wing Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Order) and center-oriented Platforma Obywatelska (Civic Platform). Other parties represented in parliament are playing the role of coalition partners for those two big, among them are center-conservative oriented PSL/Trzecia Droga (Third Way), left-wing party Lewica (Left), and far-right-wing party Konfederacja. Wolność i Niepodległość (Confederation. Freedom and Independence). They are responsible for the construction of the migration discourse in Poland in the XXI century.

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) describes a series of approaches to critically analyze texts and cultural artifacts to reveal connotations and draw out the more significant cultural narratives that these connotations support. Analysts study how language is used in discourse to (1) consider the contexts in which texts are produced, distributed, and consumed; (2) designate the ways people use texts to construct a sense of self, society, and material reality; (3) explore a deeper context in which textual features influence broader social discourse, political stances, institutional values, and choices, and to support or challenge hegemonies (Burke et al., 2015, 187).

3 Results

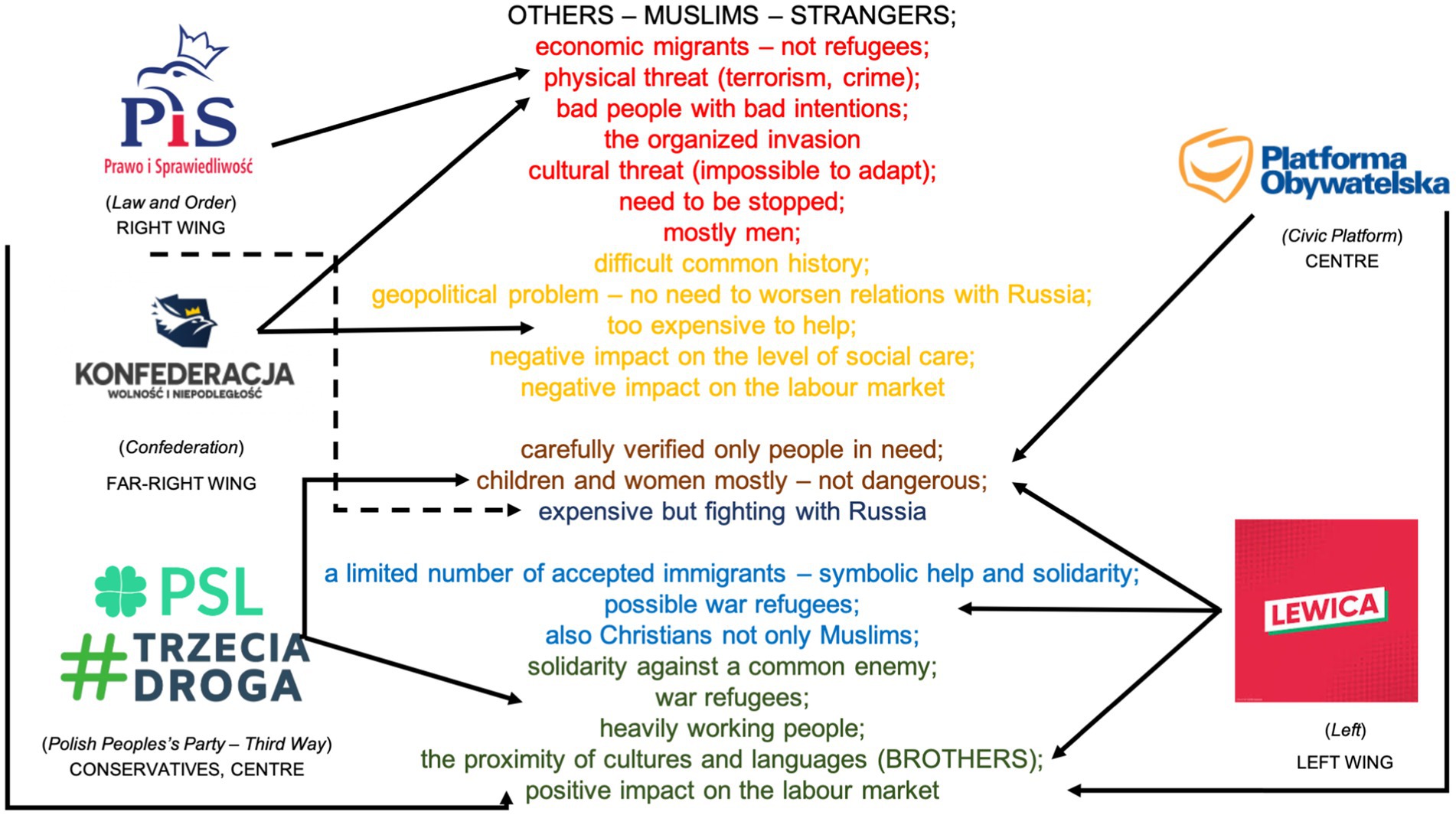

Five main Polish political parties or coalition representatives took part in the parliamentary discussions: Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Order), Platforma Obywatelska (Civic Platform), PSL/Trzecia Droga (Third Way), Lewica (Left), and Konfederacja. Wolność i Niepodległość (Confederation. Freedom and Independence). Figure 1 presents their arguments in discussing migrants in Poland during analyzed parliamentary debates and discussions.

Figure 1. Arguments posed in the discussion on migrants in Poland by political parties represented in parliament (own study).

Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Order) presents a strong anti-migrant narrative on migrants from MENA countries, calling them others and strangers, bad people with bad intentions, posing a physical threat to Poland through acts of terrorism and crimes. As Muslims, they are perceived as impossible to adapt. Their gender—men mostly—was an additional argument against them. The party refuses to recognize them as refugees. According to Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, migrants from MENA countries pose also a threat to economic security as potential beneficiaries of social welfare. They should be kept away from Poland by all, also extraordinary, measures. Strong securitization has been implemented in this case to the migration perceived as an existential threat.

In the case of refugees from Ukraine, the narrative of the right-wing party is the opposite: Ukrainians are brothers in need, war refugees, who fight with the common enemy (Russia). They are heavily working, mostly women and children so their impact on the labor market is positive. As Christians, they represent cultural similarity, so there is no problem with integration. The help should be provided on an extraordinary level (access to social security benefits, labor market, etc.), so soft securitization has been implemented as the extraordinary support for refugees is explained by the security reasons: family members of the refugees, who stay in Ukraine and fight, are countering our common enemy and stop possible Russian invasion to Poland.

Platforma Obywatelska (Civic Platform), the party that ran the Polish government during the migration crisis in 2015, presents a more moderate narrative on migration from MENA countries than Prawo i Sprawiedliwość. Party leaders argue that a limited number of carefully verified migrants will be potentially relocated to Poland, so they do not pose an existential threat to security, mostly women and children, war refugees, and Christians from Syria. The relocation was presented as a duty to the European Union. No securitization has been implemented.

In the case of refugees from Ukraine, the party narrative was similar to that presented by Prawo i Sprawiedliwość with no securitization implemented. Ukrainians were presented as brothers, people in need, culturally similar, and eager to work heavily. They pose no threat to Poland, and Poland is obliged to help them in due for fighting with Russia and for humanitarian reasons (solidarity).

PSL/Trzecia Droga (Third Way) who was co-running the government in 2015, presented a similar narrative to Platforma Obywatelska, but put a lot of attention to the verification processes of migrants from MENA countries to be relocated to Poland. They argued about solidarity with poor people forcibly displaced from their countries but expected them to integrate with Polish society. No securitization has been implemented.

In the case of refugees from Ukraine, the party narrative was similar to that presented by Prawo i Sprawiedliwość and Platforma Obywatelska. On the contrary, the party does not securitize the problem and advocates for careful verification of the offered benefits and helps only those who really deserve it.

Lewica (Left) in the case of migrants from MENA countries presents the most humanitarian and pro-migrant approach from all analyzed political parties in Poland. It argues that they need help and solidarity as war refugees, miserable human beings, humans the same as us, temporarily relocated to refugee camps in Europe, and want to live a normal life. No securitization has been implemented.

In the case of refugees from Ukraine, the party narrative was similar to that presented above, but no securitization has been implemented.

Konfederacja. Wolność i Niepodległość (Confederation. Freedom and Independence) presented the strongest anti-migrant narratives in the case of both groups: migrants from MENA countries and refugees from Ukraine. Migrants from MENA countries are described by the party as others, strangers, dangerous Muslims, who want to destroy Polish culture and pose physical threats to citizens. All of them have bad intentions, want to benefit from social welfare, are lazy, and do not want to work heavily. Rapes and crimes will be common, if relocation is accepted. As in the narrative of Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, migrants should be kept away from Poland by all, also extraordinary, measures. Strong securitization has been implemented to the migration perceived as an existential threat, one of the biggest among contemporary ones.

In the case of refugees from Ukraine, the party also presents an anti-migrant narrative. It perceives them as a geopolitical problem—the reason for worsening relations with Russia and an expensive problem that might impact negatively the labor market and social welfare. As Poland and Ukraine have a difficult common history, they might cause cultural tensions. The party argues, that with all the benefits provided to Ukrainians, Polish citizens will become second-category ones. Securitization has been implemented for the migration of Ukrainian refugees perceived as an existential threat.

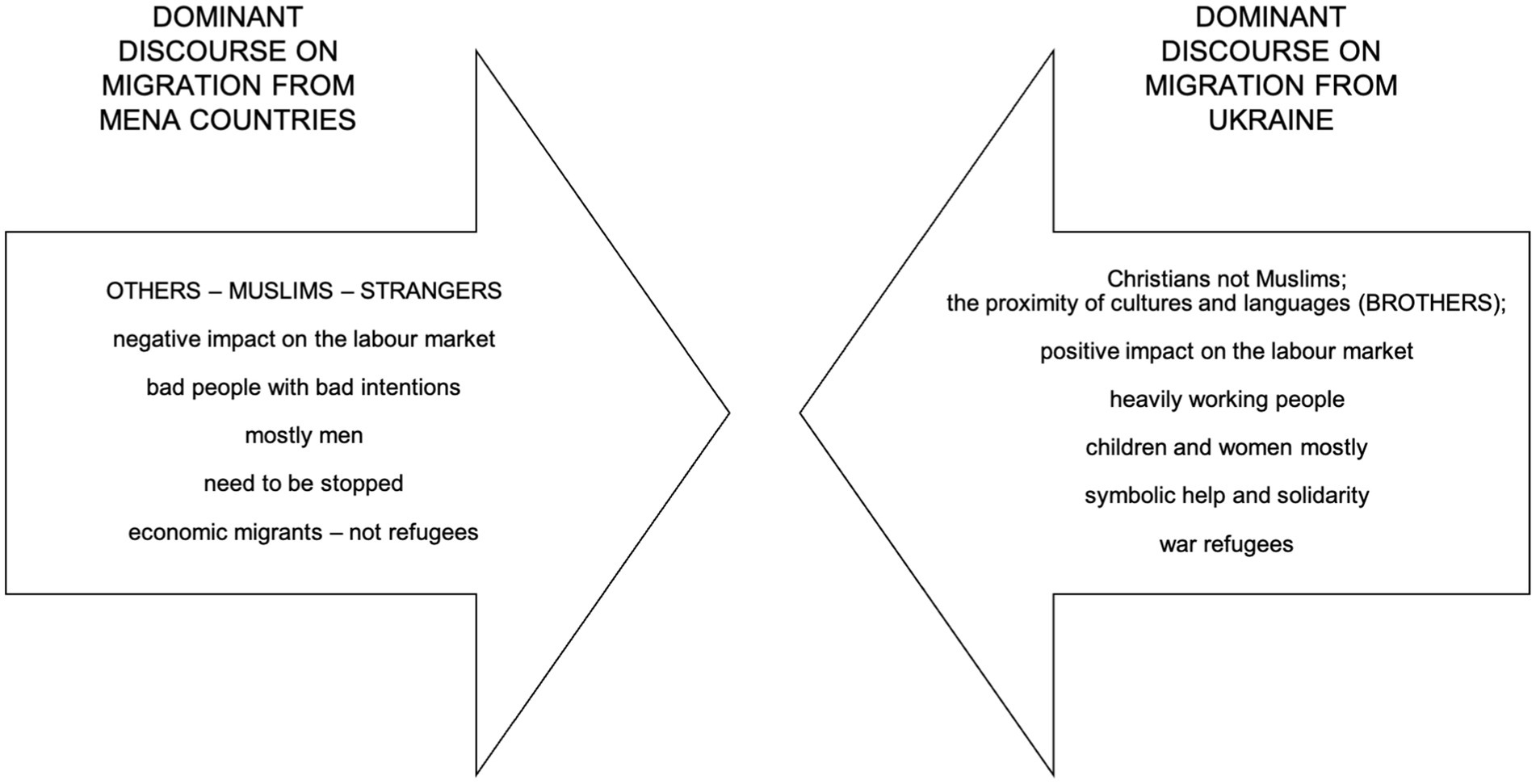

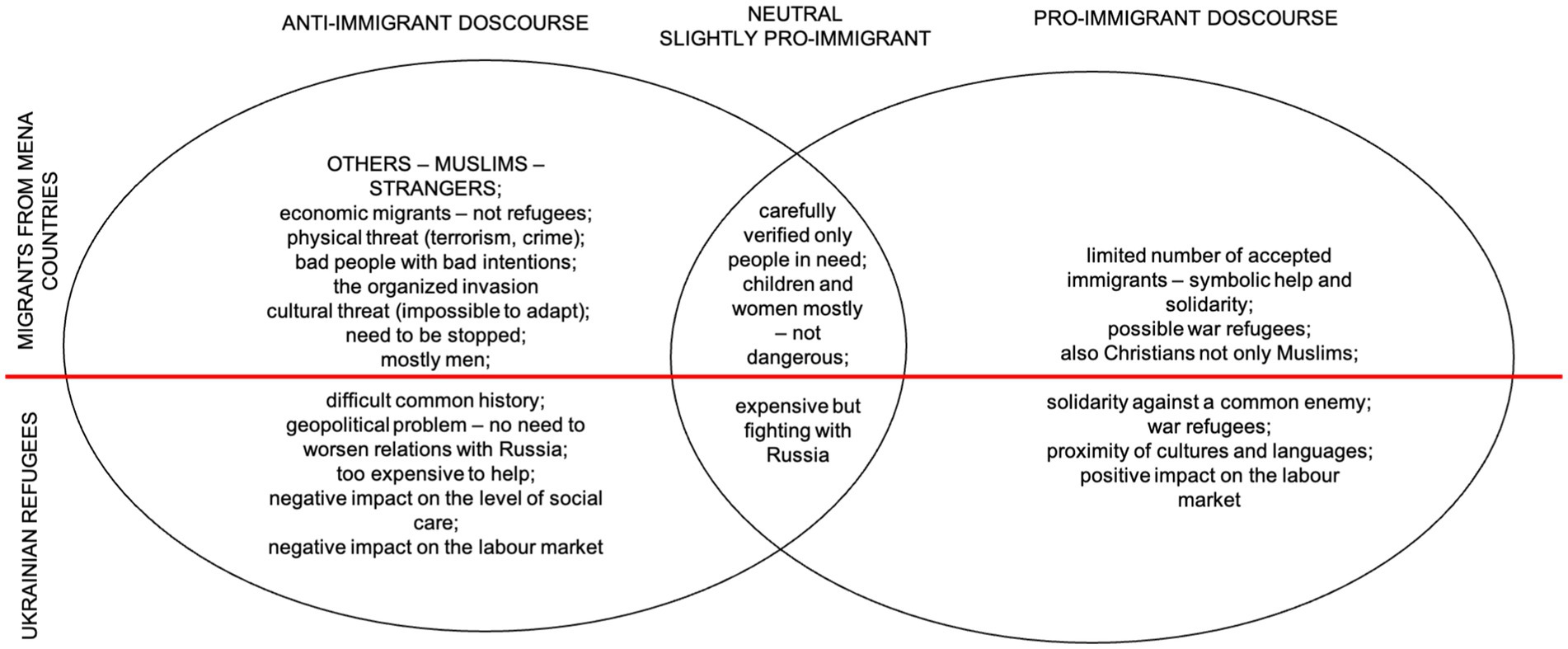

Figure 2 presents the comparative analysis of the arguments posed in the discussion on two groups of migrants in Poland, and Figure 3 highlights two main discourses on migration in Poland.

Figure 2. Comparative analysis of the arguments posed in the discussion on migrants in Poland (own study).

4 Discussion

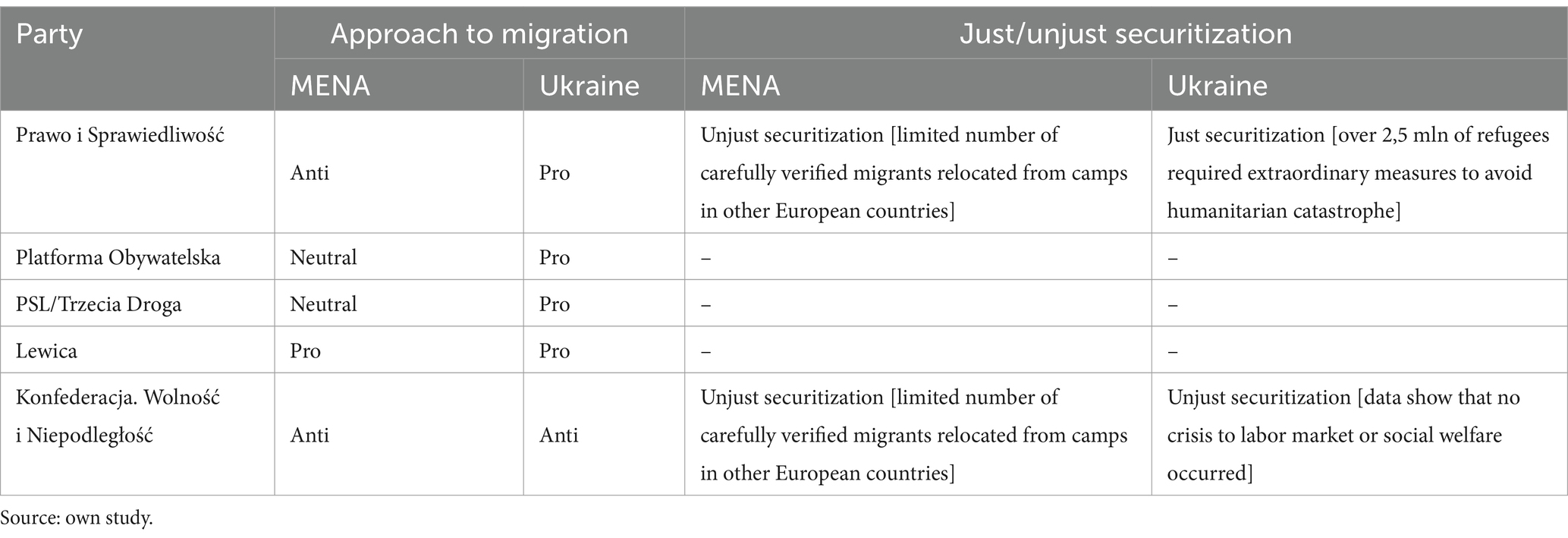

As indicated in the Results section, four cases of securitization have been indicated in the analyzed discourse of Polish political parties on migration (see Table 2). All of them have been implemented by right or far-right-wing parties: Prawo i Sprawiedliwość and Konfederacja. Wolność i Niepodległość.

Table 2. Just and unjust securitization of migration to Poland in the discourse of Polish political parties.

In the case of migrants from MENA countries, their possible arrival as a result of the relocation program proposed by the EU was presented as an existential threat to the security of Poland as a destination country and Polish citizens as a group and individuals. According to the parties, all possible extraordinary measures (such as a veto in the EU) should be implemented to stop relocation and not let migrants enter Polish territory. This securitization helped Prawo i Sprawiedliwość to win elections in 2015 and gave to Konfederacja. Wolność i Niepodległość very good result as well. Other parties did not securitize the MENA migration to Poland, although they indicated selected aspects of this topic as related to security. Platforma Obywatelska lost the 2015 elections mostly because of presenting a moderate approach to migration (corresponding to flexicuritization). However—according to Floyd’s typology—securitization implemented by Prawo i Sprawiedliwość and Konfederacja. Wolność i Niepodległość was unjust. The threat was not objectively existential: the relocation program intended to welcome a maximum 200 of migrants, who were verified in terms of security. They could not pose an objective threat to national security. This case confirms that religion and country of origin determine securitization in its unjust version.

In the case of refugees from Ukraine, securitizing parties used different strategies. Konfederacja. Wolność i Niepodległość presented Ukrainians as a threat to Poland and Polish society by worsening relations with Russia and the high cost of humanitarian help. The argument of the second-category citizenships of Polish citizens who must share limited social welfare with strangers has been raised as well as cultural aspects, such as complex common history. The party securitize the presence of war refugees in Poland as a threat to political, economic, and social security. The securitization was unjust. Data show that most war refugees come back home a few months after arriving in Europe, and the number of those, who stayed, has not exceeded the number of Ukrainian migrants in Poland before February 2022. Most of them work, pay taxes, and contribute to the Polish social security system. No crisis in labor market occurred (300 gospodarka, 2024).

On the contrary, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, who also securitized the migration of war refugees from Ukraine, used different arguments. It argues that the approach to Ukrainians is a response to an objective existential threat—Russia’s aggressive policy toward Eastern European countries. If Ukrainians do not stop it, in a year or two, V. Putin will attack other countries—the Baltic states and Poland. In the party’s narrative, by helping refugees—primarily relatives of Ukrainian soldiers—Poland reinforced them in the fight with Russia. That is why such extraordinary measures as free access to social care, the labor market, public schools for children, and healthcare are justified. In this case, the securitization was just. Over 2.5 mln refugees who crossed the border with Poland within the first few weeks of war required extraordinary measures to provide not only immediate humanitarian help but long-term care as well to avoid a humanitarian catastrophe. However, it was Russia’s aggressive policy indicated as an objective existential threat, not migration from Ukraine.

Discussed discourse examples affected the work on the new migration strategy in Poland. Issued in October 2024, the document and the practical recommendation focus on the primary reference of migration and security (entitled: Take Back Control, Ensure Security: Poland’s Comprehensive and Responsible Migration Strategy for 2025–2030; KPRM, 2024). It identifies security as the overriding priority for its proposed guidelines for migration policy, as stated in the document’s first paragraph: “Migration processes must not increase the level of insecurity in the daily lives of Polish residents. Therefore, the Migration Strategy of Poland for 2025–2030 adopts an overriding priority of security understood as a commitment to the state’s actions at all levels so that the migration processes taking place are regulated in detail and remain under control both in terms of the purpose of arrival, the scale of the influx, and the countries of origin of foreigners.” (KPRM, 2024, 3). Strong securitization is the primary tool used to justify extraordinary measures, such as tightening border controls and streamlining the border protection process or limitation in the asylum application, recommended to be implemented in Poland as a response to immigration. Although the government declares the acceptance of particular groups of immigrants, their selection is mainly to be done as a response to the needs of the internal labor market (Polko, 2025 in print) The proposals were implemented by the government coalition composed of Platforma Obywatelska, Trzecia Droga, and Lewica, so parties who previously were more open to immigration.

5 Conclusion

The growing significance of migration-related issues has led to a strong securitization of the problem, primarily driven by right and far-right parties. They shape the entire migration discourse through a security lens and reject both desecuritization and flexicuritization of migration proposed by left- or center-leaning parties. Support of society for such securitization—reflected in the backing of parties advocating this position during parliamentary elections—only reinforces this trend and encourages politicians to adopt extraordinary measures to halt migration to Poland. The potential threat posed by migration serves as a catalyst for social mobilization (Polko, 2022b) in a perilous manner, evident in the presence of hate speech and racism.

Based on a Polish case, it is possible to indicate the correlation between the country of origin of migrants (and in particular, their religion) and unjust securitization. It results in the conclusion, that not migration itself, but the sociocultural profile of immigrants is the driver for possible securitization. In the case of selected groups of immigrants, mostly from MENA countries, this securitization is unjust, based on fears, prejudices, islamophobia, and even racism. The case of war refugees from Ukraine in Poland shows that even big groups of migrants might be accepted by the receiving society, without being called dangerous strangers or mass invasions (so without securitization), if only cultural proximity is identified. It drives to the conclusion that more in-depth research should examine the problem with a strong indication of just and unjust security movements to discover the nature of the migration–security nexus as well as possible paths for desecuritization.

It is essential from a practical standpoint: in the third decade of the 21st century, Poland faces not only a growing influx of migrants from Ukraine but also from Asian and South American countries, such as India, Colombia, Nepal, and the Philippines. As the cultural proximity between these migrants and the receiving society is rather lacking, new instances of unjust securitization are likely to occur.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

PP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

300 gospodarka. (2024). Ilu uchodźców z Ukrainy jest w Polsce [AKTUALNE DANE]. Available at: https://300gospodarka.pl/news/uchodzcy-z-ukrainy-w-polsce-liczba [Accessed on 29.02.2024].

Adamson, F. B. (2006). Crossing borders: international migration and national security. Int. Secur. 31, 165–199. doi: 10.1162/isec.2006.31.1.165

Alba, R., and Foner, N. (2015). Strangers no more: Immigration and the challenges of integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Balzacq, T. (2005). The three faces of securitization: political, agency, audience, and context. Eur. J. Int. Rel. 11, 171–201. doi: 10.1177/1354066105052960

Bigo, D. (2002). Security and immigration: toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alternatives 27, 63–92. doi: 10.1177/03043754020270S105

Black, R., Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., Dercom, S., Geddes, A., and Thomas, D. S. G. (2011). The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob. Environ. Chang. 21, S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.001

Bourbeau, P. (2011). The securitization of migration: A study of movement and order. Abingdon: Routledge.

Burgess, J. P. (2011). “Introduction: security, migration and integration” in A threat against Europe? Security, migration and integration. eds. J. P. Burgess and S. Gutwirth (Brussels: Institute for European Studies), 13–15.

Burke, B. J., Welch-Divine, M., and Gustafson, S. (2015). Nature talk in an Appalachian newspaper: what environmental discourse analysis reveals about efforts to address Exurbanization and climate change. Hum. Organ. 74, 185–196. doi: 10.17730/0018-7259-74.2.185

Buzan, B., Waever, O., and de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Boulder, London: Lynne Rienner Publisher.

Ceyhan, A., and Tsoukala, A. (2002). The securitization of migration in western societies: ambivalent discourses and policies. Alternatives 27, 21–39. doi: 10.1177/03043754020270S103

Clark, M. A. (2003). Trafficking in persons: an issue of human security. J. Hum. Dev. 4, 247–263. doi: 10.1080/1464988032000087578

Czaika, M., and de Haas, H. (2013). The effectiveness of immigration policies. Popul. Dev. Rev. 39, 487–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00613.x

Dimari, G. (2022). Desecuritizing migration in Greece: contesting securitization through “flexicuritization”. Int. Migr. 60, 173–187. doi: 10.1111/imig.12837

Eroukhmanoff, C. (2018). Securitisation theory: an introduction. Available at: https://www.e-ir.info/2018/01/14/securitisation-theory-an-introduction/ (Accessed May 11, 2024).

Estevens, J. (2018). Migration crisis in the EU: developing a framework for analysis of national security and defence strategies. Comp. Migr. Stud. 6:28. doi: 10.1186/s40878-018-0093-3

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E., and Qasmiyeh, Y. M. (2010). Muslim asylum-seekers and refugees: negotiating identity, politics and religion in the UK. J. Refug. Stud. 23, 294–314. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feq022

Floyd, R. (2007). Towards a consequentialist evaluation of security: bringing together the Copenhagen and the welsh schools of security studies. Rev. Int. Stud. 33, 327–350. doi: 10.1017/S026021050700753X

Floyd, R. (2010). Security and the environment: Securitization theory and US environmental security policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Floyd, R. (2011). Can securitization theory be used in normative analysis? Towards a just securitization theory. Secur. Dialogue 42, 427–439. doi: 10.1177/0967010611418712

Floyd, R. (2014). “Just and unjust desecuritization” in Contesting security: Strategies and logics. ed. T. Balzacq (London: Routledge), 122–138.

Floyd, R. (2016a). Extraordinary or ordinary emergency measures: what, and who, defines the ‘success’ of securitization? Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 29, 677–694. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2015.1077651

Floyd, R. (2016b). “The promise of theories of just securitization” in Security studies: A new research agenda. eds. J. Nyman and A. Burke (London: Routledge), 75–88.

Foner, N., and Alba, R. (2008). Immigrant religion in the U.S. and Western Europe: bridge or barrier to inclusion. Int. Migr. Rev. 42, 360–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00128.x

García-Muñoz, T., and Neuman, S. (2012). Is religiosity of immigrants a bridge or a buffer in the process of integration? A comparative study of Europe and the United States. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labour (IZA).

Geddes, A. (2003). Migration and the Welfare State in Europe. Polit Q. 74, 150–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-923X.2003.00587.x

Goldstone, J. A. (2002). Population and security: how demographic change can lead to violent conflict. J. Int. Aff. 56, 3–22.

Goldstone, J. A., Kaufmann, E. P., and Toft, M. D. (2012). Political demography: How population changes are reshaping international security and National Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Guild, E., and van Selm, J. (2005). International migration and security. Opportunities and challenges. Abingdon: Routledge.

GUS. (2023). Rocznik Demograficzny 2023. Available at: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/rocznik-demograficzny-2023,3,17.html (Accessed May 9, 2024).

Helbling, M., and Meierrieks, D. (2022). Terrorism and migration: an overview. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 977–996. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000587

Huntington, S. (1991). The Third wave. Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press: Nornan and London.

Huysmans, J. (2006). The politics of insecurity: Fear, migration and asylum in the EU. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ipsos. (2023). https://www.tokfm.pl/Tokfm/7,103087,29915225,co-polacy-sadza-o-migrantach-w-polsce-nie-jest-az-tak-zle.html [Accessed on 29.02.2024].

Khader, B. (2015). Muslims in Europe: The construction of a “problem”, in: Europe and its nations: Politics, society and culture. Madrid: La Fabrica, 302–324.

Kivisto, P. (2014). Religion and immigration: Migrant faiths in North America and Western Europe. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

KPRM (2024). ODZYSKAĆ KONTROLĘ. ZAPEWNIĆ BEZPIECZEŃSTWO” KOMPLEKSOWA I ODPOWIEDZIALNA STRATEGIA MIGRACYJNA POLSKI NA LATA 2025–2030 [Take Back Control, Ensure Security: Poland's Comprehensive and Responsible Migration Strategy for 2025–2030], Załącznik do uchwały nr 120 Rady Ministrów z dnia 15 października 2024 r. Available at: https://www.gov.pl/web/premier/uchwala-w-sprawie-przyjecia-dokumentu-odzyskac-kontrole-zapewnic-bezpieczenstwo-kompleksowa-i-odpowiedzialna-strategia-migracyjna-polski-na-lata-2025-2030 (Accessed May 9, 2024).

Lewis, V. A., and Kashyap, R. (2013). Piety in a secular society: migration, religiosity, and Islam in Britain. Int. Migr. 51, 57–66. doi: 10.1111/imig.12095

Lohrmann, R. (2000). Migrants, refugees and insecurity. Current threats to peace? Int. Migr. 38, 3–22. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00118

Nadig, A. (2002). Human smuggling, National Security, and refugee protection. J. Refug. Stud. 15, 1–25. doi: 10.1093/jrs/15.1.1

Perocco, F. (2018). Anti-migrant islamophobia in Europe. Social roots, mechanisms and actors. Rev. Interdiscip. Mobil. Hum. 26, 25–40. doi: 10.1590/1980-85852503880005303

Polko, P. (2022a). Bezpieczeństwo w dyskursie politycznym RP (1989–2022). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Polko, P. (2022b). Just/unjust securitisation and social mobilisation. Bezpieczeństwo. Teoria i Praktyka 3, 127–139. doi: 10.48269/2451-0718-btip-2022-3-009

Polko, P. (2024). The migration-security nexus: desecuritization and the shift towards the sustainable approach. J. Modern Sci. 60, 86–104. doi: 10.13166/jms/197001

Polko, P. (2025). Security as a determinant of the preparation of migration policy of the Republic of Poland (in print). Poland: Rocznik Nauk Społecznych.

Rodrigues, T. F. (2015). “Population dynamics: demography matters” in Globalization and international security. An overview. eds. T. Rodrigues, R. G. Pérez, and S. S. Ferreira (New York: Nova Science Publishers), 33–49.

Sarli, A., and Mezzetti, G. (2020). “Religion and integration: Issues from international literature” in Migrants and religion: Paths, issues, and lenses. eds. L. Zanfrini. (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill).

Savage, T. M. (2004). Europe and Islam: crescent waxing, cultures clashing. Wash. Q. 27, 25–50. doi: 10.1162/016366004323090241

Urdal, H. (2005). People vs Mathus: population pressure, environmental degradation, and armed conflict revisited. J. Peace Res. 42, 417–434. doi: 10.1177/0022343305054089

Weiner, M. (1992). Security, stability, and international migration. Int. Secur. 17, 91–126. doi: 10.2307/2539131

Weiner, M., and Stanton Russell, S. (2001). Demography and National Security. New York: Berghahn Books.

Keywords: migration, securitization, Ukraine, Poland, MENA, discourse

Citation: Polko P (2025) Just and unjust securitization of migration: a comparative analysis of migration to Poland from MENA countries and Ukraine. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1464288. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1464288

Edited by:

Georgia Dimari, Ecorys, United KingdomReviewed by:

Stylianos Ioannis Tzagkarakis, Hellenic Open University, GreeceGeorge Kordas, Panteion University in collaboration with reviewer SIT

Dionysios Stivas, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, China

Copyright © 2025 Polko. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paulina Polko, cHBvbGtvQHdzYi5lZHUucGw=

Paulina Polko

Paulina Polko