- Fakultät für Staats- und Sozialwissenschaften, Institut für Politikwissenschaft, Universität der Bundeswehr München, Neubiberg, Germany

During the 2021 German federal election campaign, COVID-19 emerged as a highly salient issue in public discourse. Despite its significance, most political parties adopted a strategy of depoliticization, likely as a means to mitigate potential electoral losses. Against this backdrop, our paper examines whether and to what extent COVID-19 was discussed on Twitter in the run-up to the election. Our analysis draws on two original datasets collected in the four weeks preceding the election on September 26, 2021: one comprising 7,374,166 German-language posts mentioning the federal election and another with 3,195,198 German-language posts commenting on the COVID-19 pandemic. Using these datasets, we calculated echo chamber scores (ECS) based on ideological leanings within retweet-based networks and examined the politicization of COVID-19 in the digital election campaign. Our findings reveal that the online discourse polarized into two distinct echo chambers: a “safety-first” community advocating for strict COVID-19 measures, and a “freedom-first” community opposing such measures. While most political figures sought to depoliticize the issue online, key political actors – due to their leadership roles in the upcoming election-could neither avoid addressing the pandemic nor being publicly addressed on the matter. In particular, users within the echo chambers focused attention on two key health policy leaders from opposing political camps: Jens Spahn, the then-incumbent Health Minister from the Christian Democratic Unio/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), and Karl Lauterbach from the Social Democratic Party (SPD), who would later become health minister. Our results underscore that, despite efforts to minimize the salience of COVID-19 in the lead-up to the election, certain leaders were compelled to confront the “elephant in the room” due to the demands of their roles during the health crisis.

1 Introduction

Agenda-setting studies explore how issues are prioritized in public discourse and policymaking. More specifically, they examine why certain topics receive significant attention while others are ignored. A key premise of these studies is that attention is a scarce resource, but increased levels of attention are crucial for changing the status quo. When issues fail to garner sufficient attention, they remain unnoticed and unaddressed (Baumgartner and Jones, 2009, 2015). In fact, even if an issue was once a government priority, it may be removed from the agenda if it no longer attracts public or political interest. To describe this dynamic, Brosius and Kepplinger (1995) introduced the concepts of “killer issues” and “victim issues.” Killer issues dominate media coverage and public attention, displacing other topics, the victim issues, from the agenda. This competitive nature of issue attention and agenda-setting implies that, at any given moment, only a few topics can capture the attention of the public, the media, and policymakers, as both individuals and institutions have a limited capacity to focus on and process information, something Simon (1985) coined as the “bottleneck of attention.” Additionally, agenda-setting scholars have shown that those involved in the policymaking process may deliberately keep certain issues off the agenda to avoid potential negative consequences (Bachrach and Baratz, 1962, 1963; Wolfinger, 1971; Shpaizman, 2020), such as political backlash or resource allocation conflicts. This is particularly true in election years.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was a quintessential killer issue, dominating public and political discourse worldwide. As a policy issue, COVID-19 posed unique challenges due to its novelty, complexity, and rapid evolution, transforming quickly from a public health crisis to a multi-dimensional issue implicating governance, personal liberties, and the role of the state. This volatility—marked by frequent shifts in scientific understanding, public health guidelines and policy responses—complicated the landscape for voters and political actors alike. Political leaders thus faced the difficult task of balancing demands for public safety with calls for economic stability, navigating a climate charged with uncertainty. In the public sphere, attitudes were often more extreme, with conspiracy theories doubting the biological existence of the virus altogether (van Mulukom et al., 2022). Amidst these complexities, two clear political camps emerged. One camp advocated a safety-first strategy, emphasizing health-protective behaviors even at economic costs, while the other prioritized individual freedoms and favored the economy (Lembcke, 2021). During the 2021 German federal election campaign, these camps were still in place. Strikingly though, most German parties largely sidelined the issue, adopting a depoliticization approach to avoid position statements on the pandemic (Lembcke, 2021). This tactic was intended to prevent voters from reconsidering their positions at the last minute, thereby minimizing the risk of electoral losses. Considering the salience of COVID-19 in public discourse, it is, however, questionable whether parties could effectively maintain their depoliticization strategy and enforce a unified party line among all their candidates.

Against this background, this paper examines whether and to what extent COVID-19 was a topic in the context of the 2021 German federal election. More specifically, we explore public chatter on COVID-19 on the social media platform Twitter and analyze the degree of its politicization in the run-up to the election.1 First, we demonstrate that online discourse around COVID-19 polarized into two distinct echo chambers: a “safety-first” community advocating for strict pandemic measures and a “freedom-first” community opposing such restrictions. Second, we show that while most political figures sought to depoliticize the issue online, key political actors—owing to their leadership roles—could neither avoid addressing the pandemic nor evade public scrutiny on the topic. Notably, users within the two echo chambers focused attention on two prominent health policy leaders from opposing political camps: Jens Spahn, the then-incumbent Health Minister from the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), and Karl Lauterbach from the Social Democratic Party (SPD), who would later become health minister. To gain deeper insights into how political actors have adjusted their behaviors in this evolving communicative landscape, we collected all German-language tweets and retweets that mentioned the federal election, along with those discussing COVID-19, during the four weeks preceding the German federal election on September 26, 2021. This resulted in two original datasets, comprising 7,374,166 posts related to the election and 3,195,198 posts focused on the pandemic. For each of the four weeks, we constructed echo chamber scores (ECS) based on retweet-based networks and user ideological homophily (Alatawi et al., 2024).

In the following sections, we first examine issue attention during electoral campaigns, focusing in particular on party competition, echo chambers and affective polarization on social media. Second, we elaborate on our research design, including our data and methods, before presenting and, finally, discussing our results. We conclude that parties managed to avoid the elephant in the room by circumventing dialogue on Twitter on how to handle the pandemic. This strategic depoliticization of the issue meant that discussions around COVID-19 were largely left to the digital public, with little direct engagement from party-affiliated actors. However, certain political figures, particularly those in leadership roles, were compelled to engage with the issue due to the nature of their positions. We argue that the lack of broader exchange between voters and parties or party-affiliated actors on such a decisive topic can exacerbate societal dissonance and, accordingly, pose significant dangers for consensus-building in a democracy, particularly in the context of polarized echo chambers where communication remains insular and ideologically homogeneous.

2 Issue attention during electoral campaigns: the role of party competition, echo chambers and affective polarization

Electoral campaigns are crucial periods where political parties strive to capture voter attention by emphasizing specific issues while downplaying others. Understanding how issues gain or lose prominence during these campaigns provides insight into the strategies employed by political parties and their broader impact on voter behavior and key voter concerns. This section explores the interplay between party competition, echo chambers and affective polarization on social media in shaping issue attention during electoral campaigns, focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.1 COVID-19 and party competition

The COVID-19 pandemic had significant impacts on electoral processes and outcomes worldwide, affecting voting logistics and shifting voter and government priorities. Some elections were postponed, including local elections in the United Kingdom, municipal elections in Italy, and presidential primaries in the United States (US). Additionally, there was a substantial increase in mail-in and early voting to reduce in-person voting. Polling places also implemented various health and safety measures. Beyond these logistical changes, the pandemic's influence was most pronounced in how it highlighted the effectiveness of incumbent governments' crisis management. Governments that were perceived as handling the pandemic well generally garnered voter support, while those seen as ineffective faced significant backlash.

In South Korea's April 2020 elections, the first major election held during the pandemic, the left-wing Democratic Party of President Moon Jae-In achieved a decisive victory, largely due to the public's approval of the government's handling of COVID-19 (Lee, 2021). In contrast, the pandemic had a markedly different impact on the November 2020 elections in the US. Baccini et al. (2021), for instance, argue that the number of COVID-19 cases negatively affected Donald Trump's vote share compared to 2016. Similarly, Neundorf and Pardos-Prado (2022) found that Trump was held accountable for the challenging economic and political environment, facing backlash due to the economic downturn and particularly from older voters most at risk from pandemic mismanagement.

These empirical findings align with the retrospective voting assumption (Achen and Bartels, 2016; Fiorina, 1978), which suggests that the incumbency effect can positively influence the next ballot if voters are satisfied with the government's performance. Conversely, it can negatively impact the next ballot if expectations are not met. Thus, both government and opposition parties have a strategic interest in convincing the electorate of their competencies while highlighting their rivals' deficiencies. One would therefore expect negative campaigning on COVID-19 to thrive during electoral campaigns, resulting in highly politicized and polarized camps.

The selective nature of issue attention during electoral campaigns is critical to understanding these dynamics. Issue ownership theory posits that parties emphasize issues where they have a perceived advantage, aiming to increase the salience of these topics among voters to garner support (Budge, 2015; Petrocik, 1996). During the pandemic, this meant that parties known for their strong stances on healthcare or economic management would highlight these aspects to reinforce their competence. Conversely, the riding the wave theory suggests a bottom-up approach where parties respond to voters by highlighting issues that are already salient to them (Ansolabehere and Iyengar, 1994). This theory implies that during the pandemic, parties would adjust their focus based on public concerns about health and economic stability, aligning their campaigns with the most pressing voter issues.

Understanding how parties set their agenda and compete, particularly in times of crisis, is crucial—especially in the context of online communication, where echo chambers play a significant role. The next two sections examine the role of echo chambers in amplifying or mitigating the polarization observed in online discussions about COVID-19.

2.2 COVID-19 and echo chambers on social media

When analyzing the dynamics of online discussions, particularly on polarized and science topics such as climate change, it is inevitable to encounter the concept of echo chambers. Most influentially, the term “echo chamber” was coined by Jamieson and Cappella (2008, p. 76) as “a bounded, enclosed media space that has the potential to both magnify the messages delivered within it and insulate them from rebuttal.” In other words, people are predominantly exposed to attitude-consistent information while cross-cutting exposure (i.e., disagreement in viewpoints) is absent (Arguedas et al., 2022). Hence, they communicate with and listen to like-minded others and end up hearing more and louder echos of their own beliefs (Sunstein, 2018). The concept of echo chamber is often associated with homophily (McPherson et al., 2001), selective exposure (Garrett, 2009; Stroud, 2010), confirmation bias (Nickerson, 1998), and cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957).

With the advent of social media and their underlying logic of algorithmic and self-selected content management (van Dijck and Poell, 2014), research on echo chambers—and the related concept of filter bubbles—has gained strong momentum. For example, studies have focused on the fact that content on social media is tailored to individual characteristics of users, such as demographic profiles, ideological predispositions, or past behavior (Sunstein, 2018). According to techno-pessimists, such filter bubbles limit the novelty and diversity of content that users are exposed to and exacerbate online clustering and (cyber-)polarization (Terren and Borge-Bravo, 2021). However, evidence of echo chambers and resulting polarization is mixed (Barberá et al., 2015).

In a recent review of the burgeoning literature on social media echo chambers, Terren and Borge-Bravo (2021) distinguish between studies focusing either on content exposure (related to the affordances of social media), or on communication and interaction between different users (related to the use of social media). The former approach concentrates on cross-cutting content in users' news feeds. The underlying assumption is that more opinion-reinforcing content increases the likelihood of users being in echo chambers or filter bubbles (Williams et al., 2015). However, this research usually suffers from limited access to users' news feeds and relies on self-reported data, which is scarce. It also finds only little to no evidence of echo chambers (Terren and Borge-Bravo, 2021).

According to Terren and Borge-Bravo (2021), the majority of research operationalizes echo chambers as cross-cutting interactions between social media users. The latter are categorized into antagonizing, ideologically-discordant groups that are examined based on digital trace data, whereby fragmented and homogeneous publics within social media ought to reflect echo chambers and polarization (Batorski and Grzywińska, 2018). Analyses of follower and retweet networks reveal high degrees of political homophily, endorsement and ideologically-congruent interactions, while mention and reply networks are characterized by more cross-cutting interactions (Williams et al., 2015; Conover et al., 2011; Esteve Del Valle and Borge Bravo, 2018).

Most recently, echo chambers have also been identified in communication about COVID-19. For example, Wang and Yuxing (2021) found echo chamber effects in rumor rebuttal discussions about COVID-19 on Weibo in China. In their analysis of the Italian vaccination debate on Twitter, Cossard et al. (2020) discovered differences in the structures of polarized groups. Vaccine skeptics tended to form smaller but louder groups that were more tightly connected, whereas vaccine advocates organized in a more hierarchical fashion around certain authoritative actors. Investigating US tweets on wearing masks, Lang et al. (2021) observed stark rhetorical polarization between pro- and anti-mask hashtags alongside an echo chamber effect in the dominant pro-mask group that ignored the rhetoric of the anti-mask minority.

2.3 COVID-19 and affective polarization within echo chambers on social media

The concept of echo chambers on social media is closely tied to polarization, as echo chambers reinforce and amplify divisions in public opinion. Polarization can manifest in two primary forms: ideological and affective (Iyengar et al., 2012). Iyengar et al. (2012) initially related both forms to partisan identity. However, they can be transferred to opinion-based groups, as Filsinger and Freitag (2024) have shown for the case of COVID-19. Ideological polarization refers to opposing groups having widely divergent preferences on key policy issues. In echo chambers, these polarized viewpoints are reinforced as users engage primarily with others who share similar beliefs, narrowing their exposure to alternative perspectives.

Polarization is further intensified through affective polarization, where individuals develop strong positive feelings toward their own group while harboring negative or hostile sentiments toward opposing groups. In the case of COVID-19, echo chambers have contributed to heightened divides between groups advocating for different pandemic responses, fostering intergroup animosity and hostility that extends beyond policy disagreements to affective, identity-driven conflicts (Schmid et al., 2023; Filsinger and Freitag, 2024). This emotional intensity can escalate into political intolerance, where the opposing side is seen not just as wrong but as morally illegitimate (Schmid et al., 2023).

Within echo chambers, selective exposure to like-minded content fosters both ideological and affective polarization. As members of an echo chamber focus exclusively on certain aspects of an issue, they neglect broader contexts, amplifying the polarization between groups. For instance, narratives aligning with each community's preexisting beliefs become the primary focus, reinforcing in-group beliefs and further deepening both ideological and affective divides. In this way, echo chambers drive selective issue attention—a process by which users increasingly fixate on narratives that align with their community's views, thereby intensifying polarization.

Digital trace data and social network analyses offer unique insights into these dynamics, as increasing datafication quantifies human behavior on social media (Mayer-Schönberger and Cukier, 2013). This allows for tracking conversations, identifying whether opinions cluster in closed bubbles, and observing how these clusters evolve over time. Digital trace data thus enables the investigation of issue-based echo chambers and provides a foundation for understanding if and how selective focus on particular issues fuels ideological and affective polarization. Not least for these reasons, we analyze COVID-19 chatter, its politicization, and exclusivity using Twitter retweet networks. Next, we will detail our data and analysis.

3 Research design

This section outlines the research design of our study, which aims to investigate the politicization of COVID-19 on Twitter during the 2021 German federal election campaign. We begin by justifying our case study selection, highlighting the salience of COVID-19 in the public and political discourse during the election period. Following this, we detail our data collection process, which involved gathering a comprehensive dataset of election- and COVID-19-related tweets. Finally, we describe our data analysis methods.

3.1 Case study selection: COVID-19 and the 2021 German federal election

The 2021 German federal election serves as an ideal case study to examine the politicization of COVID-19. Firstly, the pandemic was a highly salient issue in public discourse during the election period, including on Twitter. Secondly, the election provides a unique opportunity to analyze how political actors navigate contentious issues in their campaigns. Lastly, Germany's consensus-oriented political system and the diversity of party positions on COVID-19 offer a rich context for investigating the role of political leadership and strategies of (de-)politicization during the run-up to an election.

3.1.1 The salience of COVID-19 during the German election campaign

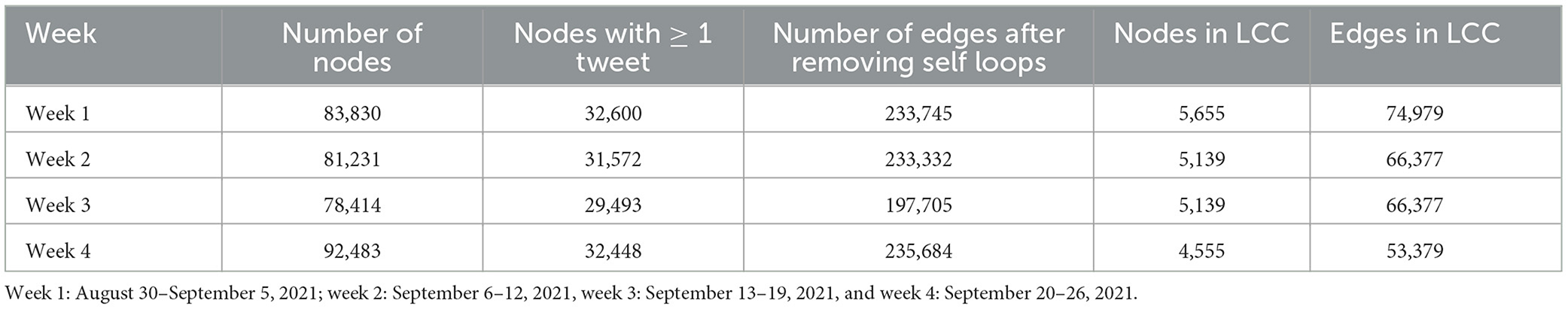

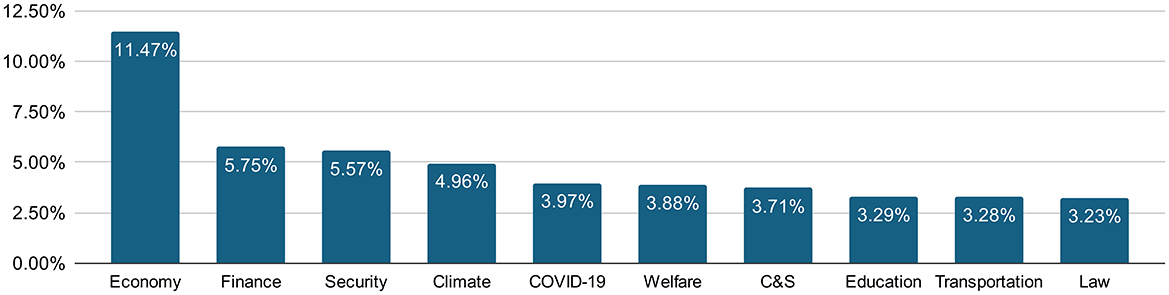

During the electoral campaign, COVID-19 was a highly salient issue in public discourse (Infratest dimap, 2021b). In the four weeks preceding the election, it emerged as the most discussed policy field within Germany's online community on Twitter, as illustrated in Figure 1.2 Over this period, a total of 7,316,545 public posts (excluding party activity) mentioned the German federal election. Of these, 4,802,328 posts specifically addressed policy issues, with over 9% of these mentions focused on COVID-19.

Figure 1. Salient issues on Twitter (percentages of all mentioned issues)—August 30 to September 26, 2021. Total tweets mentioning the federal election: 7,316,545; total tweets discussing specific policy issues: 4,802,328.

Polls on voter preferences revealed, however, that COVID-19 was not electorally decisive, as only 7% of respondents indicated that the handling of the pandemic influenced their voting decision (Infratest dimap, 2021b). The issue was primarily important for voters of the populist far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), who ranked it second (18%) to immigration (40%). After nearly two years of the pandemic, the public had grown increasingly tired of COVID-19 and accompanying restrictions on daily life (Infratest dimap, 2021b, 2022, 2021a).

Although COVID-19 was widely discussed on Twitter, most parties did not prominently feature their policy positions on pandemic-related issues in their (offline) campaigns. Six of the seven biggest parties, including the CDU, the CSU, the SPD, The Left (Die Linke), the Free Democratic Party (FDP), and the Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), focused their campaigns on other, sometimes related policy fields, such as education and the digitization of schools, the reconciliation of family and working life, and tax reduction.3 Strikingly, the AfD was the only party to directly address the pandemic in its campaign, with the slogan, “Where do we want to go? Back to normal!” featured as part of its broader campaign theme, “Germany, but normal.”

Specifically, most electoral manifestos lacked explicit positions on issues like vaccinations or mandatory masks. Likewise, COVID-19 was largely absent from campaign posters across most parties, with the AfD as an exception. The Left and the Greens made only indirect references by emphasizing healthcare and showing masked individuals in their visuals. COVID-19 did surface during televised debates, but largely as a result of questions posed by journalists rather than proactive discussion from the parties. This suggests that parties either did not consider COVID-19 a topic worth competing over or chose to avoid amplifying its salience due to the complexity of the policy problem—both approaches reflecting a strategy to depoliticize the issue. This depoliticization tactic also appeared in the limited negative campaigning on COVID-19 compared to socio-economic, socio-cultural, or ecological topics, with most of the attacks coming from the AfD (Drews et al., 2022).

In analyzing the salience of COVID-19 during the German election campaign, it is also crucial to consider the party system and the kind of competition it fosters. In pluralistic systems like Germany, the extent to which COVID-19 is politicized during elections may depend on the segmentation—that is, politically feasible coalitions vs. mathematically possible coalitions—and the fragmentation of the party system, defined by the number of relevant parties in parliament. To enhance their coalition potential, parties likely sought to avoid controversial discussions with highly antagonizing viewpoints, instead focusing on less complex and less polarized issues. This reasoning suggests that party competition over COVID-19 would be relatively low for potential coalition partners, independently of the positive or negative incumbency effect of the pandemic. This made Germany an ideal case study for our analysis of political leadership and the (de-)politicization of COVID-19 on Twitter.

3.1.2 German parties' positions on COVID-19

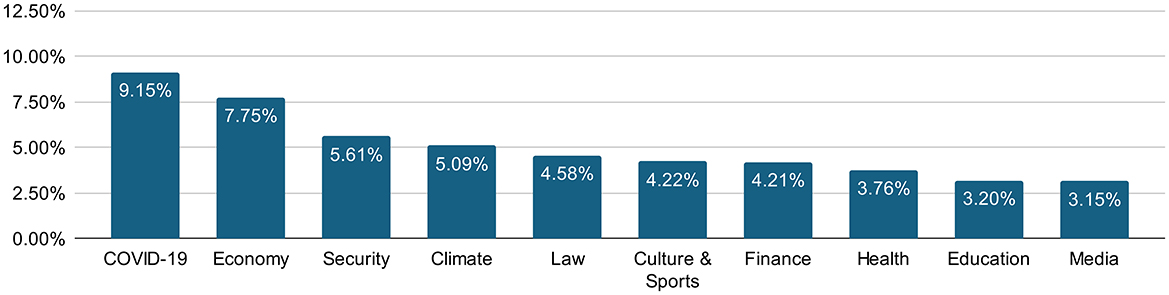

Even though most parties did not prominently feature their policy positions on the pandemic, these positions can still be derived from their manifestos and other sources. Figure 2 is based on data collected by Cicchi et al. (2021) and shows parties' stances on four COVID-19-related issues in the prelude of the 2021 German election across a dimension ranging from 0 (“safety/health-first”) to 100 (“individual freedoms/economy-first”). The issues include restrictions for vaccinated vs. unvaccinated people, compulsory masks, the priority of COVID-19 measures over economic losses, and the right to home office. Cicchi et al. (2021) positioned parties based on expert evaluations of official party documents, such as manifestos and other programmatic publications, and parties' self-positioning.

Figure 2. Distribution of COVID-19 programmatic stances (Cicchi et al., 2021).

As illustrated in Figure 2, there were three camps in the political space on COVID-19: first, The Left, the Greens, and the SPD, prioritizing health and safety measures; second, the CDU/CSU and the FDP, occupying the same space between both poles with a tendency to emphasize economic and individual freedoms; and, third, the AfD, taking a standalone extreme position on individual freedoms and economic priority.

To provide a concrete example of how parties positioned themselves on specific COVID-19-related policies, we can look at their stances regarding vaccination policies. These positions, derived from a combination of sources such as official party websites, media reports, and electoral programs, reflect varying emphases on public health vs. individual freedoms. For instance, both the SPD and the Greens strongly advocated for easing restrictions for vaccinated individuals, as highlighted in statements on their party websites.4 This stance aligns with their broader prioritization of health and safety measures, as shown in Figure 2. Similarly, the CDU/CSU, with Armin Laschet as their leading candidate, and The Left also favored easing restrictions for vaccinated individuals, as reported in the mass media.5 In contrast, the FDP—in spite of clearly recognizing the advantage of the vaccination—placed greater emphasis on individual freedom, advocating for equal treatment for vaccinated, recovered, and tested individuals, according to statements on their website (see text footnote 4). This stance positions the FDP closer to the center of the spectrum between health and economic considerations. Meanwhile, the AfD, positioned on the right of the spectrum in Figure 2, questioned the necessity of widespread vaccinations altogether in their electoral program (Alternative für Deutschland, 2021). Instead, they advocated for focusing protection efforts primarily on vulnerable populations, thus prioritizing individual freedoms over broader public health interventions. This example not only highlights the diversity of party positions but also shows how their broader ideological stances informed their approach to vaccination policies during the pandemic. It illustrates the tension between safeguarding public health and protecting individual freedoms, a key axis of debate during the 2021 election campaign.

It is important to note that the AfD failed to absorb more radical views not depicted in the continuum in Figure 2, such as those doubting the biological existence of the virus. According to Lembcke (2021, p. 85), the AfD “became a victim of ‘outbidding' by the APO [extra-parliamentary opposition].” In line with populist anti-establishment rhetoric (Mudde, 2004), the AfD initially engaged in a superficial safety-first strategy, blaming the government for its incompetence in crisis prevention and management to secure the “native” public from external threats. Only later did it switch to an individual-freedom-first stance, a change due in part to the complex nature of the policy issue. However, by accepting the existence of the virus, it left a vacuum for other, more radical groups to form, such as the German anti-COVID movement “Querdenker” and the political party “Die Basis,” which attracted a small but extreme subgroup of COVID-skeptics and conspiracy theorists (Laufer, 2021; Nachtwey et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the AfD maintained strong anti-measures positions, and the same was true for their voters (Bayerlein and Metten, 2022; Steiner, 2024). Consequently, between the 2017 and 2021 federal elections, the party lost voters who were in favor of coronavirus-related mandates (Steiner, 2024; Bayerlein and Metten, 2022).

Moreover, we also have to keep in mind that the CDU and CSU, which formed and campaigned as a joint union at the federal level, suffered from stark intra-union conflict over the general line to be taken during the pandemic, illustrating once more the complexity of the policy problem. They were torn between prioritizing safety or individual freedoms and lacked consensus on the concrete measures to be taken. Competition was particularly fierce between the two party leaders, Armin Laschet (CDU) and Markus Söder (CSU), which was partially reflected in their approaches to COVID-19. These observations suggest that enforcing a shared election strategy was particularly difficult for the CDU/CSU (Probst, 2020; Fahrenholz, 2021).

To conclude, the potential coalition parties in Germany were not on the same page regarding the specific measures to be taken during the COVID-19 pandemic. The same holds true for their electorate. Consequently, many parties adopted a depoliticization strategy throughout the election campaign to avoid contentious debates and maintain broad appeal, both online and offline. This varied positioning and strategic approach to COVID-19, coupled with the segmentation and fragmentation of the party system in Germany, make it an ideal case study for exploring issue attention, political leadership and (de-)politicization on Twitter. By examining these dynamics in a single case, we gain valuable insights into how parties and party members navigate highly polarized issues like those of the COVID-19 pandemic within a multi-party system and the strategies they employ to manage voter perceptions and coalition potential.

3.2 Data collection

To measure the extent of echo chamber effects regarding COVID-19 chatter during the election campaign and to analyze the politicization of COVID-19 online, both in terms of political actors authoring tweets and political actors being mentioned in tweets, we collected Twitter data for the four weeks preceding the 2021 German federal election using Twitter's enterprise PowerTrack API.6

We focused on German-language tweets to capture election-related discourse most relevant to the German-speaking community. While this choice may exclude some eligible voter communities and potentially include some non-voters, our aim was to capture interactions within a linguistically cohesive group. We chose not to filter by geolocation for two reasons: first, only a minority of Twitter users publish geolocational information; second, language serves as a crucial link for echo chambers of communication. Indeed, language forms a communication barrier in the sense that users interact primarily with those who are “located within rather than outside the same geographic region and ... [use] ... the same language” (Chen et al., 2017, p. 1019). Furthermore, understanding neologisms within hashtags primarily requires knowledge of a specific language (Bastos et al., 2013).

Specifically, we first collected all German-language tweets discussing the federal election between August 30 and September 26, 2021. The filter rules for this first dataset included more than 1,000 hashtags and keywords, as outlined by Müller et al. (2022).7 In addition, we collected data from over 2,000 German federal party figures who were actively participating in the election campaign. This group included Members of Parliament (MPs) in office until the 2021 election; candidates running in the 2021 election; leading candidates of the 2021 election, as well as other prominent political figures, including Angela Merkel; and official party accounts at both the national and state levels.8 Our search resulted in a list of 2,139 unique user IDs, and yielded 7,374,166 posts. Based on this dataset, we analyzed and compared the topics that the digital public and the party figures mentioned when talking about the election campaign which, in turn, allowed us to assess the degree of (de-)politicization of COVID-19 compared to other policy issues.

Additionally, for the same period (August 30 and September 26, 2021), we collected 3,195,198 German-language posts that addressed COVID-19 but were not necessarily directly related to the election campaign. For this second dataset, we compiled a list of nearly 300 relevant keywords and hashtags that were prevalent in the discourse on the pandemic, such as “distanzunterricht” (remote learning), “impfpflicht” (mandatory vaccination), or “#STIKO” (Germany's Standing Committee on Vaccination).9 This second dataset allowed us to analyze the presence of echo chamber effects within the digital discourse surrounding the pandemic, as well as both the direct activity of party figures and how frequently they were mentioned by the users of these polarized communities.

We did not conduct a comprehensive evaluation for inauthentic or coordinated malicious activity. However, we performed several checks, all of which revealed no suspicious patterns. Specifically, we examined for astroturfing behavior, such as temporal and message patterns (e.g., co-tweeting and timing of posts) (Keller et al., 2020). Additionally, we assessed the similarity between posts (not including identical ones) and flagged any extraordinary volumes of activity without a clear contextual reason (e.g., a TV debate). For our echo chamber analysis, we qualitatively analyzed the 100 most active and most retweeted users within each community on a week-by-week basis.

3.3 Data analysis

Building on the method of retweet-based networks, we measured the echo chamber score (ECS) developed by Alatawi et al. (2024) to analyze echo chamber effects. Following this, we analyzed the extent of politicization within our communities, focusing on political actors and their presence in the conversation, as well as the frequency with which they were mentioned by users of these closed communities.

3.3.1 Measuring echo chamber effects

First, we examined the extent to which public discourse on COVID-19 was structured in echo chambers during the critical phase of the German federal election campaign. To do this, we analyzed the 3,195,198 posts related to the topic and measured echo chamber effects using the method outlined by Alatawi et al. (2024).

Alatawi et al. (2024) developed the ECS, a metric designed to measure echo chamber effects based on user characteristics and their interactions, such as retweets. These interactions are used to model a homophilic network, meaning connections between ideologically similar users. The ECS quantifies the echo chamber effects by measuring both cohesion within groups and the separation between different groups. Cohesion is determined by the average distance between a user and other members within their community, reflecting how ideologically cohesive a community is. Separation measures the average distance to the nearest other communities, indicating how distinct each community is from others. To assess the ideological similarity of users and use it to compute the ECS, Alatawi et al. (2024) introduced the EchoGAE model, a specialized form of graph autoencoder designed to position users based on their tweets and interaction networks.

In our study, we performed the network analyses on a weekly basis to control for echo chamber effects and politicization over time. Moreover, and unlike Alatawi et al. (2024), we utilized the Leiden algorithm instead of the Louvain algorithm for community detection. The Leiden algorithm is more effective in identifying meaningful communities within larger datasets (Traag et al., 2019). Additionally, we employed directed graphs to capture the directionality of communication flows between users. We set a threshold of 100 users as the minimum community size to ensure meaningful analysis.

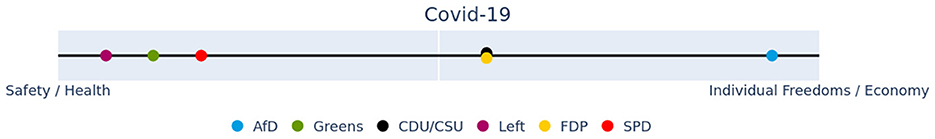

Table 1 gives an overview of the data we used for calculating the ECS. The “number of nodes” (column 2) refers to the total number of unique users in each week. Since the ECS measures ideological distance based on original posts, we only considered users who posted at least once (column 3). Column 4 lists the total number of retweets (edges) connecting these users, excluding self-retweets (column 5), where users retweeted their own posts. The data used for our analyses were drawn from the largest connected component (LCC) (column 6), which represents the largest group of interconnected users, where each user can reach every other user.

3.3.2 Analyzing issue attention and (de-)politicization

Second, we analyzed issue attention toward COVID-19 and the (de-)politicization of the topic during the election campaign. To do this, we first examined the general attention political figures devoted to COVID-19 in comparison to other policy issues. We used the dataset of 7,374,166 posts mentioning the German federal election and measured how frequently the 2,139 party-affiliated figures commented on political topics. For the issue analysis, we created a dictionary containing 1,402 expressions, which were assigned to 32 distinct political topics.

Next, we focused specifically on the politicization within the COVID-19 echo chambers, using ECS results from the 3,195,198 posts related to the pandemic. In both the freedom-first and safety-first communities, we analyzed users' activity and mentions, particularly focusing on the then-incumbent German Health Minister, Jens Spahn, and his competitor, Karl Lauterbach, who would later become the new health minister. The activity of these health policy leaders provides insights into their direct contributions to the COVID-19 debate on Twitter, while the mentions reflect the attention they received from users during the election campaign.

4 Results

This section presents the key findings of our analysis on the (de-)politicization of COVID-19 during the 2021 German federal election, with a particular focus on echo chamber effects and the engagement of political figures within the polarized discourse. First, our findings reveal two distinct echo chambers—one favoring strict COVID-19 measures (the safety-first community) and the other prioritizing individual freedoms (the freedom-first community). Second, we found that political parties devoted relatively little attention to COVID-19 on Twitter, even as the public discourse was dominated by the issue. Finally, our analysis highlights the central role of key health policy leaders, particularly Jens Spahn and Karl Lauterbach, in the COVID-19 debate.

4.1 Echo chamber effects and affective polarization in COVID-19 networks

Our network analysis, in combination with the ECS measure, resulted in two distinct communities for each of the four weeks: a safety-first group, which advocated for adhering to COVID-19 health protocols such as vaccinations, mask mandates, and social distancing; and a freedom-first group, which opposed COVID-19 health recommendations, emphasizing individual freedoms, social and economic concerns, and, in some cases, even questioning the existence of the virus itself. This clear separation illustrates the polarized nature of public discourse on the pandemic.

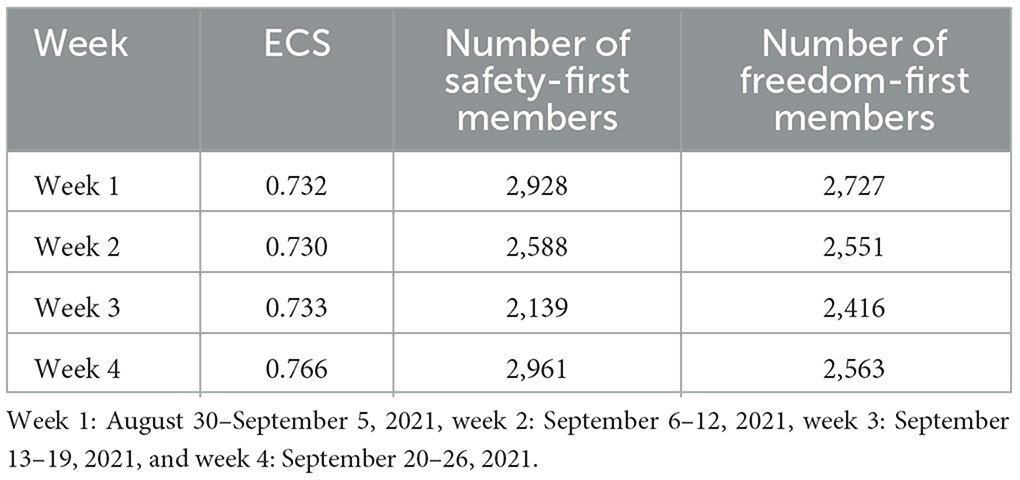

Table 2 shows both the number of members in each community and the degree of echo chamber effects (ECS) for the topic of COVID-19. An ECS value above 0.5 indicates a significant echo chamber effect. When comparing our results with those of Alatawi et al. (2024), who analyzed the online discourse on abortion (ECS = 0.626) and guns (ECS = 0.714) in the US, it becomes clear that while both topics showed heated, polarized debates, the COVID-19 discussions during the German federal election campaign displayed even stronger echo chamber effects. This suggests that the pandemic, as a highly politicized issue, generated stronger ideologically isolated communities in Germany compared to the US abortion and gun debates.

Table 2. Weekly ECS and number of members for freedom-first and safety-first communities during Germany's federal election 2021.

The safety-first community, which averaged 2,654 unique users per week, was primarily composed of individuals who retweeted content supporting public health measures, including messages from medical professionals, scientists, journalists and traditional media outlets, and politicians like Karl Lauterbach.

In contrast, the freedom-first community, which averaged 2,564 users per week, was composed of users opposed to state intrusion into personal liberties. This group frequently retweeted anti-vaccination messages and content from leaders of the German anti-COVID movement, conspiracy theorists, populists and journalists associated with spreading related content (e.g., Manaf Hassan, Alexander Kissler, and Ernst Wolff). A prominent example of this narrative is a retweet that claimed, “Gates and Rockefeller foundations fund WHO guidelines for the digital vaccination card. The connection between ID2020 and vaccination cards is slowly becoming abundantly clear.”10

Despite their opposing views, both the safety-first and the freedom-first communities used similar normative argumentation, citing the protection of children—either from the virus itself or from the social and psychological effects of complying with pandemic regulations—as a key concern. Consequently, both camps engaged in discussions around education, particularly concerning the impact of COVID-19 on children's everyday lives, such as their treatment in schools, compulsory testing, and homeschooling. In the safety-first community, hashtags like #kinderdurchseuchungstoppen (“#stopchildcontamination”) and #protectthekids were prevalent.11 Conversely, in the freedom-first community, hashtags such as #kidsfreedomday or #lasstdiekinderinruhe (“#leavethekidsalone”) were frequent.12 This focus on children's welfare was particularly salient in September 2021, coinciding with the start of the school year and the heightened concerns of parents and educators. Posts like the following two exemplify the sentiments in each camp:

My child is not responsible for your health!

No more compulsory masks in schools!

No more compulsory masks in schools!

No more quarantine for healthy children!

No more quarantine for healthy children!

No more distancing, no more cuddling, no more contact restrictions!

No more distancing, no more cuddling, no more contact restrictions!

#leavethemkidsalone #children's troop.13

A small calculation example: if 0.01% of children infected with #covid19 die from the virus, then a #epidemic affecting all children under 12 in Germany statistically means about 1,100 dead children. By way of comparison, 46 children under 12 died in road traffic in 2019.14

Despite both communities centering their arguments around children's welfare—whether from the virus itself or from the perceived harm of pandemic regulations—the tone and framing of their messages reflected deep-seated affective polarization. In the freedom-first community, for instance, state-imposed COVID-19 regulations were described in severe terms, with some users referring to mandatory measures as a form of “child abuse” and accusing politicians of using children as “guinea pigs.” This language underscores a sense of personal threat, with individuals vowing resistance against the perceived encroachment on their rights and freedoms. Such statements reveal how polarization extended beyond policy disagreements, creating a hostile atmosphere where members of each community not only disagreed with opposing views but felt deeply antagonistic toward those who held them. This emotional divide fostered a strong in-group identity, intensifying the perceived moral divide between communities and framing the opposing group as not just misguided, but as morally culpable.

4.2 Issue attention and the politicization of COVID-19 in Twitter echo chambers

To understand how political parties navigated the COVID-19 discourse on Twitter during the 2021 German federal election, we examined both the supply and demand sides of politics. On the supply side, we analyzed the attention political figures and parties actively devoted to the topic. On the demand side, we explored how frequently they were mentioned by users of the community. Our analysis used several metrics to capture the dynamics of party involvement: the general party engagement on Twitter on the topic of COVID-19, the fraction of tweets authored by parties and party affiliates, and the frequency with which parties and individual politicians were mentioned by users of the two communities.

4.2.1 Supply side: party engagement on Twitter regarding COVID-19

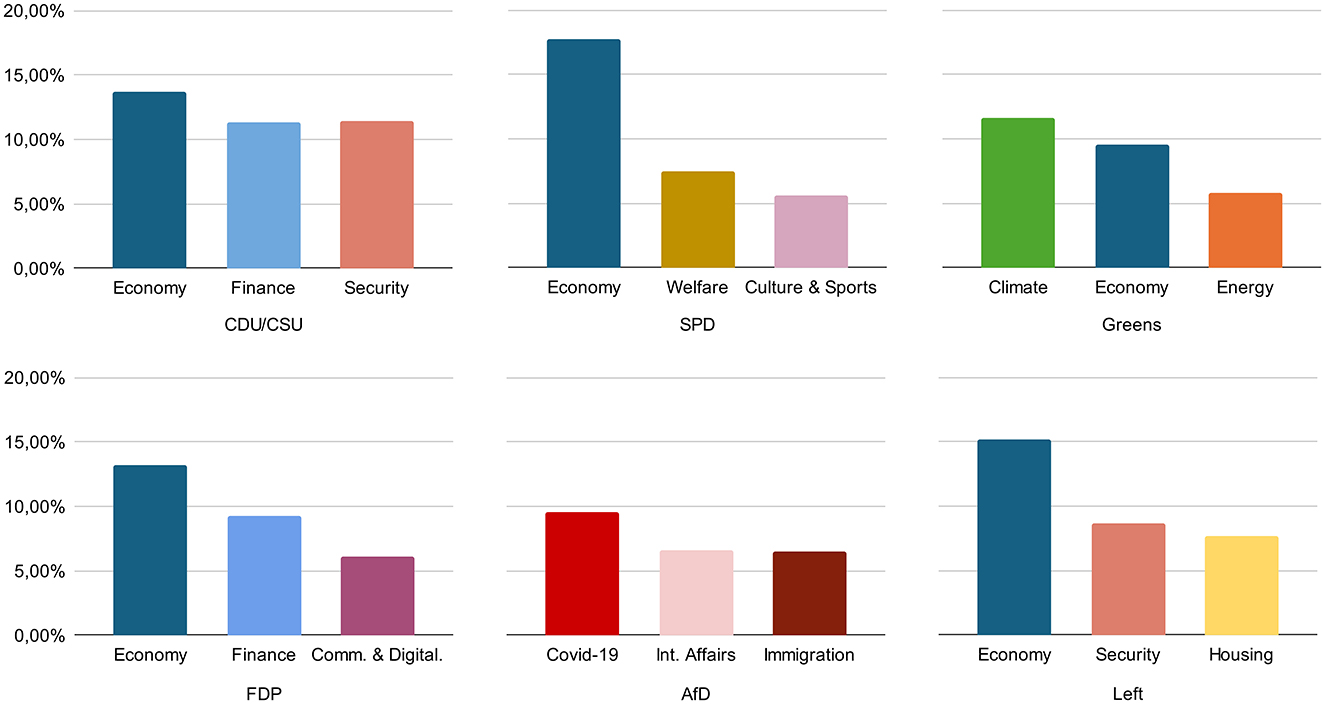

As shown in Figure 3, COVID-19 was not a dominant topic in the engagement of German political figures on Twitter during the four weeks leading up to the election. Only a small fraction of political actors' issue mentioning— <4%—addressed the pandemic, despite its overwhelming presence in public discourse. Instead of focusing on COVID-19, political figures concentrated on topics such as the economy (11.47%), finance (5.75%), security (5.57%), and climate (4.96%). This stands in contrast to the dominance of the issue within the broader digital public sphere (cf., Figure 1).

Figure 3. Most frequent issue mentions by parties, August 30–September 26, 2021. Total amount of tweets: 57,571. Total amount of issue mentions within these tweets: 43,247.

This relatively low engagement with COVID-19 aligns with comments made by then-Health Minister Jens Spahn, who emphasized the importance of keeping the pandemic from becoming an election issue, as had been the case in the US (Deutschlandfunk, 2021). He later remarked in a post-election interview that stricter coronavirus health measures “got stuck ... for electoral reasons” (Merkur.de, 2021).

When we examine party-specific engagement on COVID-19, notable differences in their focus become evident. Figure 4 compares the top issues discussed by political figures, grouped by party, during the election campaign. While most parties prioritized the economy or climate, the AfD stands out as the only party to have discussed COVID-19 more frequently than other topics, even though these mentions accounted for less than 10% of their overall discourse. This higher emphasis on the pandemic provides nonetheless insights into their programmatic focus during the election.

Figure 4. Top three of issue mentions by political figures (in %), grouped by party, August 30–September 26, 2021.

As described in Section 3.1.2, during the pandemic and the election campaign, the AfD was a “populist entrepreneur” (Hansen and Olsen, 2022), portraying the government and its COVID-19 policies as dangerous (Wondreys and Mudde, 2022). Their messages targeted voters dissatisfied with the Merkel government's handling of the crisis. When further analyzing the AfD's engagement within the polarized echo chambers identified in Section 4.1, we find evidence that the party held the highest share of tweets within the freedom-first community. This consistent presence reinforces the AfD's alignment with the anti-restriction movement, positioning the party as the primary voice for those communicating in isolated, ideologically homogeneous groups that are strongly tied together in their communication patterns.

In addition to this general pattern, the key health policy leaders, Jens Spahn and Karl Lauterbach, displayed distinctive engagement with the COVID-19 discourse, which did not easily align with traditional left-right political divides. As the then-incumbent Health Minister, Spahn's activity oscillated between the two polarized communities throughout the campaign. In Week 1, he was primarily active within the freedom-first community, while in Weeks 2 and 3, his engagement shifted to the safety-first community. By Week 4, however, Spahn returned to the freedom-first community. This oscillation likely reflects Spahn's role as Health Minister, where he had to address concerns from the polarized ends of the debate, balancing demands of the ongoing health crisis with political considerations. Additionally, it highlights the volatile nature of the COVID-19 issue. As scientific understanding and public sentiment evolved, Spahn's shifting positions also underscores the challenge of responding to a multifaceted crisis that resisted categorization within conventional party lines. Karl Lauterbach, by contrast, was highly active in the COVID-19 discussions on Twitter, advocating for stricter health measures while remaining independent of either echo chamber. His activity showed no affiliation with either community, reflecting his strategy of offering science-based, neutral stances. In essence, these dynamics reveal that political figures in leadership positions, particularly those with decision-making power like Jens Spahn, are compelled to engage with both supportive and critical communities, even if they are highly polarized. This is especially evident in the run-up to an election, where their role forces them to address key issues from various perspectives, balancing their responses to appeal to different groups within heated debates.

4.2.2 Demand side: echo chambers calling for political leaders

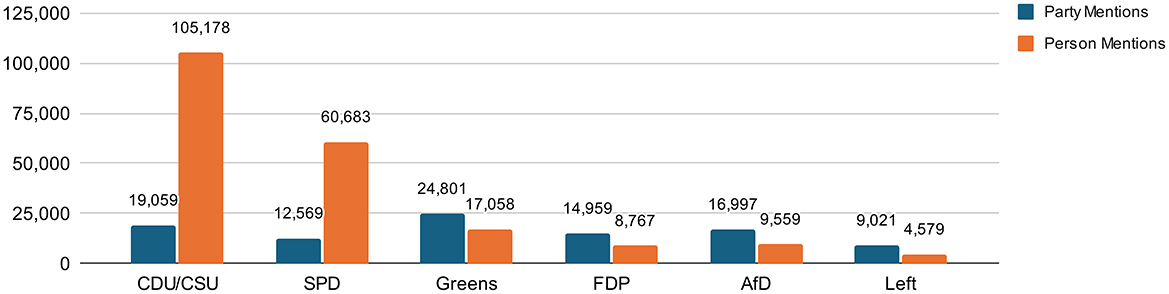

To further analyze how political figures were called upon by the public, we also examined the demand side, focusing on users belonging to one of the two COVID-19 echo chambers. While political parties largely sought to depoliticize the pandemic during their campaigns, the public continued to engage with COVID-19 as a highly salient issue. Users of these communities practiced a highly personalized discourse when it came to politics, focusing on political figures from the CDU/CSU and SPD. When analyzing the postings of users within each community, as referenced in Table 2 for the entire COVID-19 dataset of 3,195,198 tweets, we can see a clear pattern of personalization in the discussion. Figure 5 shows that—of all political figures, institutional and individual—individuals (represented by the orange bar) were mentioned much more often than party organizations (blue bar), reinforcing the trend toward personalization in the political discourse. This highlights the degree to which the discourse centered on individual leadership, with mentions of key political figures, especially from the CDU/CSU and SPD, surpassing those of the parties themselves.

Figure 5. Number of party vs. person mentions by users belonging to echo chamber communities, grouped by party (total = 324,298 mentions).

The emphasis on individual leaders, particularly Jens Spahn, the incumbent Health Minister from the CDU, and Karl Lauterbach, his challenger from the SPD, underscores the public's focus on these figures in managing the health crisis. Despite efforts by the parties to downplay the salience of COVID-19, the public discourse remained focused on the leadership and actions of these prominent figures.

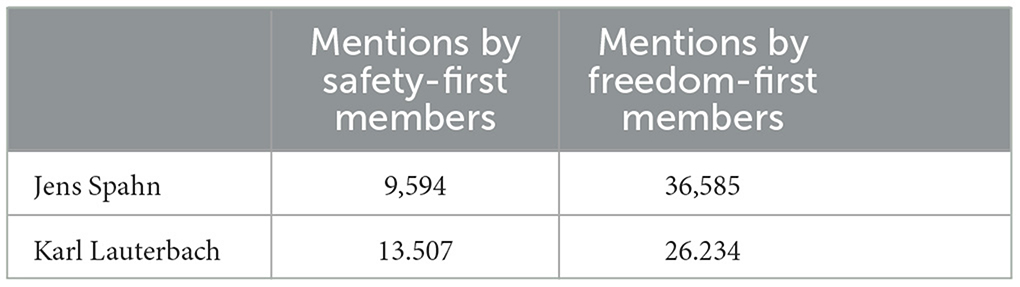

Table 3 highlights the mentions of Jens Spahn and Karl Lauterbach within the two polarized COVID-19 echo chambers: the safety-first and the freedom-first communities. Notably, Jens Spahn was referenced significantly more by members of the freedom-first community (36,585 mentions) compared to the safety-first community (9,594 mentions). This likely reflects his role as a central figure in implementing COVID-19 restrictions. Within the safety-first community, Spahn's measures were often seen as inadequate or not sufficiently stringent to protect public health, leading to dissatisfaction over what was perceived as a failure to prioritize safety. On the other hand, the freedom-first community regarded him as the symbol of restrictive measures that severely limited individual freedoms. Spahn, as the face of the COVID-19 response, became the target of frustration in this group, viewed as enforcing state control over personal liberties. This tension is evident in comments such as “@jensspahn. If the defamation of the #unvaccinated is enforced like this, then in 4 months it will be the turn of the #obese, then the #smokers, then the #gays etc. Until the ideal #Homo #Hygienicus is created.” This reflects how Spahn's policies, especially regarding vaccination, were perceived as infringing on individual rights, generating significant backlash.

Table 3. Mentions of Jens Spahn and Karl Lauterbach, number of mentions by users that belong to COVID-19 echo chambers.

Similarly, Karl Lauterbach, a vocal advocate for stricter COVID-19 measures and a prominent health policy expert, was also mentioned more frequently by the freedom-first community (26,234 mentions) than by the safety-first community (13,507 mentions). Despite his strong alignment with the safety-first approach, Lauterbach was seen as a key figure to challenge Spahn's policies. Within the safety-first community, he was viewed as the scientifically grounded counterpart to Spahn, representing hopes for stronger pandemic measures, particularly regarding the protection of children and a more proactive approach for the winter of 2021/2022. Mentions like “@Karl_Lauterbach what do you say to the madness here NRW? ... This is endangering the welfare of children... What else is this @ArminLaschet doing? Children have also died of Covid!” illustrate how he became a focal point for concerns about schools, hospitals, and vaccinations.

These dynamics show how both figures, despite attempts by political parties to depoliticize COVID-19, could not avoid being at the center of public discourse. Spahn, as the sitting Health Minister, had to engage with both critical and supportive communities, while Lauterbach emerged as a leading figure advocating for more stringent health measures. This personalized debate underscores once more the polarization of the online COVID-19 discussion during the German federal election.

5 Discussion

The results of our analysis provide several important insights into the nature of COVID-19 discourse during the 2021 German federal election and highlight the interplay between echo chambers, polarization, and the personalization of political discourse. This discussion reflects on these findings, considering their implications for our understanding of agenda-setting, (de-)politicization strategies, and the role of key political figures during election campaigns, and acknowledges the limitations of our study.

5.1 Echo chamber effects and affective polarization

Our findings reveal a strongly polarized public discourse surrounding COVID-19, with the emergence of two distinct communities—the safety-first and freedom-first advocates. These echo chambers reflect the broader societal divide over the pandemic, particularly in relation to public health measures and individual freedoms. The ECS values observed in our analysis, which exceed 0.7 across all weeks, indicate that discourse was not only polarized but also ideologically isolated. This suggests that users within each community were exposed primarily to like-minded views, with limited engagement across the ideological divide.

Comparing these results with those of previous studies on contentious topics such as gun control and abortion in the US (Alatawi et al., 2024), it becomes evident that COVID-19 debates in Germany during the election campaign were even more polarized. The stark division between the safety-first and the freedom-first communities illustrates how the pandemic had become a deeply polarized issue, with discussions reflecting not only policy preferences but also broader normative and ideological conflicts about governance, personal liberty, and the role of the state.

Furthermore, our analysis highlights how affective polarization intensified this divide. Language within the freedom-first community, for instance, described COVID-19 measures in severe terms—such as “child abuse”—and cast political leaders as morally reprehensible figures exploiting children. Such hostile framing underscores that COVID-19 discourse involved not only ideological polarization but also strong emotional divides, with each group viewing opposing positions as morally threatening. This affective component exacerbated the lack of constructive dialogue, as individuals became entrenched in not only their policy stances but also their emotional allegiance to one side.

Our findings thus reinforce existing research on echo chambers and polarization on social media. As Sunstein (2018) and Williams et al. (2015) have argued, social media can amplify opinion-reinforcing content and limit cross-cutting exposure, creating echo chambers where users become more entrenched in their beliefs. In the context of COVID-19, this suggests that public health debates were not only polarized but also largely insulated from counterarguments, potentially contributing to further societal divisions during a critical election period.

5.2 Depoliticization by political parties

Despite the dominance of COVID-19 in public discourse, our analysis of party engagement on Twitter reveals that political figures largely avoided the topic online. Less than 4% of all issue mentions by political figures were related to COVID-19, with parties instead focusing on economic issues, finance, security, and climate. This depoliticization strategy is in line with previous research suggesting that parties may deliberately downplay contentious issues during election campaigns to avoid alienating potential voters (Bachrach and Baratz, 1962; Shpaizman, 2020).

From an issue ownership perspective, COVID-19 presented unique challenges that further incentivized parties to depoliticize the policy problem. Issue ownership theory posits that voters rely on parties' established reputations to navigate complex issues (Downs, 1957; Budge and Farlie, 1983). However, COVID-19's evolving scientific understanding, shifting public health guidelines, and multi-dimensional impacts on governance and personal liberties made it difficult for parties to establish a clear position. This complexity likely compounded their decisions to avoid competing over COVID-19, opting instead to emphasize familiar and/or indirectly related topics like economic recovery, where voter preferences were more predictable.

Interestingly, the AfD was the only party to place COVID-19 more prominently in its discourse, albeit accounting for less than 10% of their mentions. This aligns with the AfD's role as a populist entrepreneur (Hansen and Olsen, 2022), leveraging public dissatisfaction with the government's handling of the pandemic to mobilize support. By focusing on individual freedoms and anti-restriction narratives, the AfD positioned itself as a key voice within the freedom-first community, further polarizing the debate and appealing to voters frustrated with COVID-19 measures.

The relative silence on COVID-19 from all other parties reflects their efforts to avoid the elephant in the room, i.e., to depoliticize the issue, likely in recognition of its potential to divide the electorate. As noted by Jens Spahn, the pandemic was not meant to become a central issue in the election campaign (Deutschlandfunk, 2021), and stricter health measures may have been delayed for electoral reasons (Merkur.de, 2021). This suggests that political actors consciously sought to shift the public focus away from COVID-19, both offline and online, emphasizing less contentious issues such as economic recovery and climate policy.

5.3 Personalization of political discourse

Although political parties may have sought to depoliticize COVID-19, the public's focus on key political figures, particularly Jens Spahn and Karl Lauterbach, highlights the highly personalized nature of the debate. Our analysis shows that both Spahn and Lauterbach were central figures in the COVID-19 discussion, with their names mentioned far more frequently than their respective parties.

The difference in how Spahn and Lauterbach were positioned within the echo chambers is also notable. Spahn, as the sitting Health Minister, oscillated between the safety-first and freedom-first communities, reflecting his role as a central figure in the government's pandemic response. This shifting engagement likely indicates Spahn's need to balance competing demands from different segments of the electorate—a challenge made even more complex by the specific nature of the COVID-19 crisis as a policy issue, which involved rapidly evolving scientific insights and polarized public sentiment. These factors further intensified the difficulty of navigating the issue during an election campaign marked by heightened polarization.

Lauterbach, on the other hand, was more consistently aligned with the safety-first community, where he was seen as a trusted health expert advocating for stricter COVID-19 measures. His absence from the freedom-first discourse suggests that he was viewed as a symbol of the scientific consensus on public health, in contrast to the more politically contentious figure of Spahn. This difference underscores how political figures can become symbols for broader societal debates, with their personal reputations and public personas shaping how they are perceived across different ideological communities.

5.4 Implications for democratic discourse

The findings of our study have significant implications for democratic discourse in the digital age. The observed echo chamber effects, combined with the depoliticization strategies of political parties, point to a growing disconnect between public discourse and party platforms. This gap risks intensifying polarization and weakening trust in democratic institutions, as critical issues like COVID-19 remain largely unaddressed in broad public forums. The lack of engagement across echo chambers further limits opportunities for constructive dialogue and consensus-building, which are essential for a healthy deliberative democracy. As different segments of the electorate become increasingly isolated from one another, finding common ground on critical policy issues becomes more challenging, potentially deepening social divides.

5.5 Limitations and future research

While our findings offer valuable insights into the politicization and echo chamber effects surrounding COVID-19 during the 2021 German federal election, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, our analysis is based on a single-case: Although this approach offers a focused and in-depth exploration of how political actors navigated a highly salient issue within a multi-party system, our findings are inherently shaped by the German context, which may limit their applicability to other countries. Future research could build upon these insights by examining similar dynamics in diverse electoral settings to better understand how issues like COVID-19 are politicized across different political systems. Comparative analyses would further enrich our findings and clarify the role of various political structures in shaping issue attention and public discourse.

Second, our study focuses on the COVID-19 issue and the associated echo chambers. We did not investigate other contemporaneous debates that may have also exhibited echo chamber effects or differing degrees of politicization. For instance, examining discussions around other salient topics during the same time period, such as Germany's withdrawal from Afghanistan, could provide a more comprehensive perspective on how issues are politicized differently within echo chambers. Testing whether front-runner political figures, such as party leaders or prominent ministers, are also heavily mentioned or depoliticized in other issue-specific echo chambers would help validate the broader comparative merit of our approach.

These limitations suggest that while our study offers an important case-specific analysis, future research could build on this by expanding the geographical scope and exploring other issue domains to deepen our understanding of (de-)politicization within echo chambers and the personalization of political discourse.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because according to our contract with X/Twitter, we are not allowed to disclose the data collected via the API to third parties. However, the Tweet IDs of the posts used for this analysis can be provided upon request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to amFzbWluLnJpZWRsQHVuaWJ3LmRl.

Author contributions

JR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. WD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization. FR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors acknowledge the financial support received for this research from dtec.bw - Center for Digitalization and Technology Research of the German Bundeswehr. dtec.bw was funded by European Union - NextGenerationEU.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andreas Dafnos, Arthur Müller, and Andreas Neumeier for their support with data curation and formal analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Twitter/X is particularly suitable for our study due to its popularity among political parties and candidates, who use the platform for campaigning. Indeed, individual political actors can advertise their programmatic stances and thus circumvent official gatekeepers within their parties (Ceron et al., 2022; Vergeer, 2015; Stier et al., 2018; Jungherr, 2016). Unlike publications by journalists and mass media, Twitter also offers unmediated and detailed insights into public attitudes and preferences.

2. ^Details on how the data for this figure were obtained are provided in the Data Collection section. Briefly, we calculated the number of tweets in our dataset that featured key terms associated with various policy issues to highlight COVID-19's relative salience during the election period.

3. ^For instance, the FDP focused on education and innovation (Freie Demokraten, 2021), the Greens concentrated on climate, welfare, and family (Bündnis 90. Die Grünen, 2021), and the SPD highlighted their candidate for Chancellor Olaf Scholz as a testimonial for their competence in welfare (Clement, 2021). The CDU and CSU did not have a clear focus initially, but Armin Laschet later presented a team of experts (“future team”) for a diverse set of policy issues, including the economy, digitization, education, and family (CDU, 2021; Hermann, 2021). The Left prioritized welfare and social justice.

4. ^These statements were temporarily available on the official party websites during the 2021 German federal election campaign. However, they do not appear to have been archived and are no longer accessible online.

5. ^Cf., for example, Müller-Lancé and Saul (2021).

6. ^For a detailed description of how we retrieved data from Twitter, cf., Neumeier et al. (2023).

7. ^The filter rules included hashtags and keywords directly related to the German federal election. They covered general election topics, campaign events and outcomes. To create the filter rules, we conducted extensive monitoring of German political discussions on Twitter prior to the analysis, and updated our list on a weekly basis with new, relevant hashtags and keywords emerging during the campaign.

8. ^For the list of candidates, we referred to Sältzer et al. (2021). For all other political figures, we followed a standardized procedure. First, we entered full names into the Twitter search function. If a clearly identifiable result appeared, we added the handle to our dataset. For accounts not formally verified by Twitter, we corroborated their authenticity through qualitative checks. This included verifying whether the account's Twitter bio linked to a party account or an official website. We also assessed the content of posts, such as images of the individual with others, mentions of affiliated individuals, and other contextual indicators. If this initial search yielded no results, we conducted a Google search using the full name with the term “Twitter.” The resulting handles were then cross-checked on Twitter and included in our dataset only if they were qualitatively shown to match the users' Twitter account. Additionally, we reversed the process by checking if the individual had an official website or a mention on a party website that linked to their Twitter profile. If both approaches failed to produce reliable results, no Twitter account was assigned to that person.

9. ^This list and the resulting data collection were completed in four steps. First, we applied a dictionary developed by Müller et al. (2022, p. 139), which contained 81 terms “gathered as part of an in-depth press review and monitoring of the public debate on Twitter from July 1 until September 26, 2021.” Second, using this initial list, we filtered relevant data from our first dataset. Third, we analyzed all 15,808 hashtags within this selection for their relevance to the pandemic. Finally, we selected the relevant unique hashtags and retrieved all corresponding posts via Twitter's enterprise PowerTrack API.

10. ^Fourth most retweeted post in Week 2.

11. ^#stopchildcontamination and #protectthekids refer to the risks of contagion for children due to face-to-face schooling, the lack of vaccination for them and the need for wearing masks.

12. ^These hashtags refer to the demand for face-to-face teaching, social interaction, and the relaxation of measures, such as testing.

13. ^Most retweeted post in Week 1 within the freedom-first community.

14. ^Most retweeted post in Week 3 within the safety-first community.

References

Achen, C. H., and Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for Realists. Why Elections do not Produce Responsive Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400882731

Alatawi, F., Sheth, P., and Liu, H. (2024). “Quantifying the echo chamber effect: an embedding distance-based approach,” in Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, ASONAM '23 (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 38–45. doi: 10.1145/3625007.3627731

Alternative für Deutschland (2021). Deutschland. Aber normal: Programm der Alternative für Deutschland für die Wahl zum 20. Deutschen Bundestag: Beschlossen auf dem 12. Bundesparteitag der AfD in Dresden. Available at: https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/20210611_AfD_Programm_2021.pdf (accessed October 7, 2024).

Ansolabehere, S., and Iyengar, S. (1994). Riding the wave and claiming ownership over issues: the joint effects of advertising and news coverage in campaigns. Public Opin. Q. 58, 335–357. doi: 10.1086/269431

Arguedas, A. R., Robertson, C. T., Fletcher, R., and Nielsen, R. K. (2022). Echo chambers, filter bubbles, and polarisation: A literature review. Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/echo-chambers-filter-bubbles-and-polarisation-literature-review (accessed October 7, 2024).

Baccini, L., Brodeur, A., and Weymouth, S. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 US presidential election. J. Popul. Econ. 34:739–767. doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00820-3

Bachrach, P., and Baratz, M. S. (1962). Two faces of power. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 56, 947–952. doi: 10.2307/1952796

Bachrach, P., and Baratz, M. S. (1963). Decisions and nondecisions: an analytical framework. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 57, 632–642. doi: 10.2307/1952568

Barberá, P., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., Tucker, J. A., and Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right: is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychol. Sci. 26, 1531–1542. doi: 10.1177/0956797615594620

Bastos, M. T., Puschmann, C., and Travitzki, R. (2013). “Tweeting across hashtags: overlapping users and the importance of language, topics, and politics,” in Proceedings of the 24th ACM conference on hypertext and social media, 164–168. doi: 10.1145/2481492.2481510

Batorski, D., and Grzywińska, I. (2018). Three dimensions of the public sphere on Facebook. Inf. Commun. Soc. 21, 356–374. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1281329

Baumgartner, F. R., and Jones, B. D. (2009). Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226039534.001.0001

Baumgartner, F. R., and Jones, B. D. (2015). The Politics of Information: Problem Definition and the Course of Public Policy in America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bayerlein, M., and Metten, A. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on the support for the German AfD: jumping the populist ship or staying the course? Polit. Vierteljahresschr. 63, 405–440. doi: 10.1007/s11615-022-00398-3

Brosius, H.-B., and Kepplinger, M. H. (1995). Killer and victim issues: issue competition in the agenda-setting process of German television. Int. J. Public Opinion Res. 7, 211–231. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/7.3.211

Budge, I. (2015). Issue emphases, saliency theory and issue ownership: a historical and conceptual analysis. West Eur. Polit. 38, 761–777. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1039374

Budge, I., and Farlie, D. J. (1983). Explaining and Predicting Elections: Issue Effects and Party Strategies in Twenty-three Democracies. London: Allen and Unwin.

Bündnis 90. Die Grünen (2021). Bundestagswahl 2021: Unsere Kampagne zur Bundestagswahl: Bereit, weil ihr es seid. Available at: https://www.gruene.de/artikel/unsere-kampagne-bereit-weil-ihr-es-seid (accessed October 7, 2024).

CDU (2021). Experten statt Experimente. Available at: https://www.cdu.de/artikel/experten-statt-experimente (accessed October 7, 2024).

Ceron, A., Curini, L., and Drews, W. (2022). Short-term issue emphasis on Twitter during the 2017 German election: a comparison of the economic left-right and socio-cultural dimensions. Ger. Polit. 31, 420–439. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2020.1836161

Chen, W., Tu, F., and Zheng, P. (2017). A transnational networked public sphere of air pollution: analysis of a twitter network of pm2.5 from the risk society perspective. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20, 1005–1023. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1303076

Cicchi, L., Drews, W., and Reiljan, A. (2021). Dataset of political issue-positions of 15 German parties for the 2021 federal election voting advice applications Euandi (available upon request).

Clement, K. (2021). SPD stellt Wahlkampagne vor: Scholz, Scholz und nochmals Scholz. Available at: https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/btw21/spd-kampagne-bundestagswahl-101.html (accessed October 7, 2024).

Conover, M., Ratkiewicz, J., Francisco, M., Gonçalves, B., Flammini, A., and Menezer, F. (2011). “Political polarization on Twitter,” in Proceedings of the Fifth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media Political, 89–96. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v5i1.14126

Cossard, A., De Francisci Morales, G., Kalimeri, K., Mejova, Y., Paolotti, D., and Starnini, M. (2020). “Falling into the echo chamber: The Italian vaccination debate on Twitter,” in International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM). doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v14i1.7285

Deutschlandfunk (2021). Gesundheitsminister zu Corona-Auflagen. Spahn (CDU) weiterhin für das Tragen von Masken in Innenräumen. Available at: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/gesundheitsminister-zu-corona-auflagen-spahn-cdu-weiterhin-100.html (accessed October 7, 2024).

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. J. Polit. Econ. 65, 135–150. doi: 10.1086/257897

Drews, W., Riedl, J., and Steup, J. (2022). Under pressure: Spatial dynamics and party-level strategies in negative campaigning during the 2021 German election. Unpublished manuscript, presented at the GOR conference in Berlin.

Esteve Del Valle, M., and Borge Bravo, R. (2018). Echo chambers in parliamentary Twitter networks: the Catalan case. Int. J. Commun. 12, 1715–1735.

Fahrenholz, P. (2021). Was Söder weiβ - und Laschet nicht glaubt. Available at: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/meinung/corona-politik-markus-soeder-armin-laschet-csu-cdu-reiserueckkehrer-1.5365800 (accessed October 7, 2024).

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781503620766

Filsinger, M., and Freitag, M. (2024). Asymmetric affective polarization regarding COVID-19 vaccination in six European countries. Nat. Sci. Rep. 14:15919. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66756-w

Fiorina, M. P. (1978). Economic retrospective voting in American national elections: a micro-analysis. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 22, 426–443. doi: 10.2307/2110623

Freie Demokraten (2021). Nie gab es mehr zu tun. Wahlprogramm der Freien Demokraten. Available at: https://www.fdp.de/sites/default/files/2021-06/FDP_Programm_Bundestagswahl2021_1.pdf (accessed October 7, 2024).

Garrett, R. K. (2009). Echo chambers online? Politically motivated selective exposure among Internet news users. J. Comput. Med. Commun. 14, 265–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01440.x