- 1Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Center for Comparative and International Studies, ETH, Zurich, Switzerland

- 3Department of Sociology, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 4Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 5Department of Infectious Diseases and Public Health, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

This paper investigates how state-led and popular nationalism in China construct borders as tools of exclusion, reinforcing national identity amidst global populist movements. Using the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as a case study, the analysis examines Global Times articles and corresponding user-generated content to reveal how geopolitical, ideological, and emotional borders are created and maintained through nationalist discourse. State-led nationalism emphasizes cooperation and diplomacy, framing borders to position China as a global leader promoting shared prosperity. In contrast, popular nationalism—expressed through user-generated comments—manifests in a confrontational, exclusionary discourse that delineates China from external adversaries, particularly Western powers. Through a mixed-methods approach—combining word frequency, sentiment, and emotional categorization using the NRC Emotion Lexicon—this study uncovers key differences between the two forms of nationalism. State narratives construct inclusive borders that foster international engagement, aligning with China’s diplomatic ambitions. Meanwhile, popular nationalism reflects heightened emotional intensity, especially through expressions of fear, anger, and opposition, creating rigid borders that emphasize ideological conflict and national pride. The research contributes to the literature on populism and border studies by demonstrating how Chinese nationalism functions as both a state strategy and a grassroots expression, delineating “the people” from “the other.” It highlights the critical role of media—both state-controlled outlets and user-generated platforms—in constructing and reinforcing these boundaries. As populism continues to shape political discourse globally, the study offers valuable insights into how nationalism in non-Western contexts mirrors broader populist strategies of identity formation through the construction of symbolic and emotional borders.

1 Introduction

Nationalism plays a crucial role in shaping political identities and reinforcing boundaries between “us” and “them” (Anderson, 1983; Zhao, 2005). In China, nationalism operates on multiple levels, blending state-led initiatives with popular sentiments to construct a collective national identity. This identity is not simply a product of shared culture and history but emerges from political narratives that determine who belongs within the nation and who is positioned as an outsider (Zhao, 1998; Liu and Ma, 2018).

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long employed nationalism as a strategic tool to legitimize its governance, casting itself as the defender of national sovereignty and the driver of economic advancement (Zhao, 2005). Through state-controlled media, educational campaigns, and policy initiatives, the CCP promotes a narrative emphasizing unity, prosperity, and China’s rightful emergence as a global leader (Zhao and Zhang, 2024; Zhang and Jamali, 2022). This form of nationalism, carefully orchestrated to align with the CCP’s objectives, aims to foster social cohesion and popular support (Zhao, 1998; Yang and Chen, 2020).

Alongside this state-led narrative, popular nationalism has gained momentum, particularly through user-generated content on online platforms, which amplify grassroots voices (Yang and Zheng, 2012). This form of nationalism is often spontaneous, emotive, and reactionary, surfacing in response to international events or perceived threats to China’s national interests (Zhang, 2022; Shi and Zhang, 2024). While popular nationalism can complement state narratives, it also introduces complexities by challenging or diverging from the official messaging (Zeng and Sparks, 2019; Zhang and Xu, 2022). These tensions reflect the dynamic interplay between state narratives and public sentiment, complicating the construction of national identity.

1.1 Theoretical framework

The intersection of nationalism and populism offers valuable insights into how both state-led and popular forms of nationalism define national identity and construct borders. Populism, particularly in the Laclaudian sense, functions as a political logic that frames “the people” in opposition to “the elite” or “the other” (Laclau, 2005; De Cleen and Stavrakakis, 2017). In China, both the CCP and grassroots nationalist movements employ narratives that delineate authentic Chinese identity by constructing symbolic boundaries against external and internal adversaries (Brubaker, 2017).

Borders in this framework are not limited to physical boundaries but also serve as discursive constructs that define inclusion and exclusion (Anderson, 1983; Yuval-Davis et al., 2019). Media plays a critical role in constructing these borders, framing narratives that highlight certain identities while marginalizing others (Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez, 2020; Carlson, 2007). In the digital age, user-generated content further shapes this dynamic by allowing individuals to participate in the ongoing construction of national identity and borders (Valladares et al., 2020; Zhang, 2022). These narratives reflect broader struggles over belonging, identity, and legitimacy, positioning nationalism and populism as powerful forces in border-making processes.

1.2 Research gap and research questions

While extensive research has explored both state-led and popular nationalism in China, the interplay between these two forms of nationalism remains underexamined, particularly in the context of foreign policy initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Most studies treat state-led and popular nationalism as distinct entities, neglecting how they interact in constructing geopolitical and ideological borders (Zeng and Sparks, 2019; Zhang and Wu, 2017). Additionally, the role of media in mediating these interactions and shaping border construction remains a critical gap in the literature.

This study addresses these gaps by investigating how state-led and popular nationalism in China construct borders—geopolitical, ideological, and emotional—as tools of exclusion and identity formation. The analysis centers on the BRI, which offers a rich case for examining how nationalism operates across official narratives and public discourse. Specifically, the study seeks to answer the following research questions:

• RQ1: How does state-led nationalism, as expressed in media coverage of the BRI, construct borders to define China’s national identity and its role in the world?

• RQ2: How does popular nationalism, as reflected in user-generated content on BRI-related articles, construct borders that may diverge from or challenge state narratives?

• RQ3: What are the implications of these constructions for understanding the interplay between nationalism, populism, and border-making in the Chinese context?

By exploring these research questions, the study aims to contribute to the broader discourse on nationalism, populism, and border studies. It highlights the need for a critical understanding of how government narratives and public sentiments interact to shape national identity and foreign policy. In doing so, it provides insights into the tensions and convergences within China’s nationalist discourse, revealing how the construction of borders reflects and reinforces the dynamic relationship between state power and public sentiment.

1.3 Structure of the paper

The paper unfolds in five sections. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on nationalism, populism, and border studies, with a focus on their application within the Chinese context. Section 3 outlines the methodology, explaining the mixed-methods approach used to analyze the Global Times articles and user-generated content. Section 4 presents the findings, identifying key differences and similarities in border construction between state-led and popular nationalism. Section 5 provides a critical discussion of the implications of these findings for theories of nationalism, populism, and border-making, and explores their significance for understanding China’s evolving national identity. Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the main insights and offering suggestions for future research.

2 Literature review and theoretical framework

This section examines the theoretical foundations of nationalism, populism, and border construction, with a specific focus on their manifestations in the Chinese context. Through a critical engagement with the existing literature, it clarifies the dynamics between state-led and popular nationalism in China and demonstrates how both forms employ borders as tools for exclusion, identity construction, and political legitimacy.

2.1 Nationalism, populism, and borders: theoretical perspectives

Nationalism is a complex, multi-faceted construct that fosters a sense of collective identity, often rooted in shared history, culture, and values (Anderson, 1983). It creates symbolic and territorial boundaries that define who belongs within the national community and who is excluded as an outsider. Beyond reinforcing social cohesion, nationalism functions as a powerful political tool, legitimizing state authority and mobilizing public sentiment (Zhao, 2005; Liu and Ma, 2018). In China, nationalism is particularly significant, operating not only to consolidate internal unity but also to frame the nation’s global role as it seeks to restore its historical prominence.

Populism, by contrast, operates as a discursive logic that divides society into antagonistic groups, typically framing “the people” in opposition to “the elite” or “the other” (Laclau, 2005; De Cleen and Stavrakakis, 2017). While nationalism emphasizes unity within the nation, populism mobilizes individuals by constructing boundaries between groups, often using emotionally charged rhetoric. These two concepts frequently intersect: nationalist populism frames the nation as a morally pure community threatened by external or internal enemies, combining the unifying elements of nationalism with the antagonistic logic of populism (Brubaker, 2017).

The intersection of nationalism and populism is particularly relevant in China, where both state-led and popular nationalist discourses play a role in constructing symbolic boundaries. On the one hand, the Chinese state uses nationalist narratives to promote unity, emphasizing sovereignty, development, and resistance to foreign interference (Zhao, 1998). On the other hand, popular nationalism, often expressed through user-generated content, mobilizes public sentiment against perceived external threats and rivals. This convergence aligns with Brubaker’s (2017) observation that populist nationalism thrives on the construction of emotional and symbolic borders, dividing the national community from outsiders and reinforcing exclusionary identities.

Borders, within this framework, are not just physical demarcations but also discursive tools that delineate social, ideological, and geopolitical boundaries (Yuval-Davis et al., 2019). These symbolic borders determine who is included or excluded from the national community. Both state-controlled media and user-generated content contribute to these processes, actively shaping narratives that define the boundaries of national identity (Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez, 2020). Media outlets frame specific identities as representative of the national community while marginalizing others, reinforcing exclusionary dynamics. Through public participation on digital platforms, individuals contribute to constructing and contesting these boundaries, often in ways that challenge official state narratives.

This study conceptualizes borders as fluid and dynamic constructs, continuously negotiated through interactions between state and public narratives. The BRI serves as an ideal case study to explore these processes. The BRI reflects how China’s state-led nationalism attempts to build inclusive, cooperative borders that project national strength while emphasizing international partnerships. However, popular nationalist discourse, particularly online, often constructs exclusionary borders, framing the BRI as part of a broader ideological and geopolitical struggle. These divergent narratives reflect the dual nature of nationalism in China, where both unity and division are simultaneously mobilized to reinforce national identity and geopolitical boundaries.

In summary, the interaction between nationalism, populism, and border-making illustrates how borders are socially constructed and continuously reshaped through state-led and public discourse. Nationalism provides the emotional foundation for collective identity, while populism mobilizes public sentiment through exclusionary logic. Together, they shape the dynamic interplay between inclusion and exclusion that defines national identity and geopolitical boundaries in the Chinese context.

2.2 Characteristics of Chinese nationalism

Chinese nationalism emphasizes unity, sovereignty, and historical rejuvenation, reflecting the country’s efforts to reclaim its status as a global power (Zhao, 2005; Liu and Ma, 2018). This narrative draws on China’s experiences with colonialism, internal strife, and economic reform, reinforcing themes of resistance to foreign interference and national renewal (Zhao, 1998). Nationalism in China serves as a tool for domestic cohesion and political legitimacy, aligning citizens’ loyalty to the state with the authority of the CCP (Zhao, 2005).

State-led nationalism, strategically promoted by the CCP, seeks to maintain social cohesion and strengthen the Party’s control. This form of nationalism frames patriotism as a moral duty, intertwining loyalty to the nation with allegiance to the Party (Liu and Ma, 2018). Through state-controlled media, education campaigns, and cultural initiatives, the government disseminates a narrative that portrays China’s rise as a peaceful development with mutual benefits for the world (Zeng and Sparks, 2019; Zhao and Zhang, 2024).

Popular nationalism emerges from grassroots expressions of national pride, often characterized by emotional intensity and reactive tendencies (Yang and Zheng, 2012). Digital platforms provide space for individuals to express nationalistic sentiments on international and domestic issues, sometimes in ways that diverge from state narratives (Zhang and Xu, 2022). Popular nationalism can amplify confrontational attitudes, reinforcing borders between China and external rivals, particularly in moments of geopolitical tension (Shi and Zhang, 2024).

The interaction between state-led and popular nationalism reveals the multiplicity of voices shaping Chinese nationalism (Tang, 2016; He and Tang, 2024). While the state aims to channel nationalistic sentiment to support its policies, popular nationalism introduces unpredictable elements that complicate this effort (Zhao, 1998; Zhang and Xu, 2022). In some cases, public pressure has even forced the state to adopt harsher diplomatic stances than initially intended, demonstrating the influence of grassroots nationalism on policymaking (Shi and Zhang, 2024).

2.3 Nationalism and populism in China

The intersection of nationalism and populism in China becomes evident through the narrative construction of “the people” against “the other.” The CCP adopts populist strategies by framing itself as the legitimate representative of the Chinese people, standing against both foreign adversaries and domestic dissenters (Zeng and Sparks, 2019). State-controlled narratives celebrate China’s achievements and resilience, especially in response to external pressures, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Zhang, 2022). These narratives aim to unify citizens by emphasizing national pride and collective strength.

In contrast, popular nationalism on digital platforms often expresses more intense and confrontational sentiments, rallying against perceived external threats. Netizens actively defend national identity, drawing sharp symbolic borders against foreign powers, multinational corporations, and cultural influences (Yang and Zheng, 2012; Zhang and Xu, 2022). This form of populist nationalism reflects a readiness to confront external adversaries and reinforces borders through emotional expressions, such as anger and fear (Zhang, 2022).

Brubaker (2017) argues that populist nationalism thrives on the construction of borders by mobilizing “the people” through exclusionary rhetoric. In China, both state-led and popular nationalist discourses emphasize sovereignty and resistance to foreign interference, reinforcing national identity by drawing clear boundaries between China and the outside world (Zhao, 2005). The CCP’s patriotic education campaigns exemplify this process, promoting vigilance against foreign threats and cultivating a sense of national pride (Zhao, 1998).

2.4 Media, user-generated content, and border construction

The media plays a pivotal role in constructing and reinforcing symbolic borders within nationalist and populist discourses (Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez, 2020). State-controlled outlets like Global Times function as vehicles for disseminating state-led narratives, aligning with the CCP’s goals by framing China’s initiatives—such as the BRI—as symbols of peaceful development and mutual benefit (Zeng and Sparks, 2019). These narratives position China as a global leader and reliable partner, constructing borders that emphasize inclusion and cooperation (Arifon et al., 2019; Zhang and Qiu, 2022).

User-generated content—such as comments on news articles and social media posts—reflects the realm of popular nationalism, which operates both in alignment with and in opposition to state narratives (Valladares et al., 2020; Zhang, 2022). These platforms provide space for more emotive and confrontational expressions, amplifying nationalist sentiments in ways that state-controlled media cannot fully regulate (Shi and Zhang, 2024). Through these digital interactions, individuals actively participate in the ongoing construction of national identity and symbolic borders (Zhang and Xu, 2022).

Border studies emphasize that borders are socially constructed through discourse and practice, not merely defined by physical boundaries (Yuval-Davis et al., 2019). Both media narratives and user-generated content play essential roles in shaping these borders by determining who belongs to the national community and who remains excluded (Brubaker, 2017; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017). In the Chinese context, the dynamic between state-led media and grassroots expressions highlights the contested nature of border construction in response to domestic and international developments.

2.5 The belt and road initiative as a case study

The BRI provides a relevant case study for examining how state-led and popular nationalism construct borders. Launched in 2013 by President Xi Jinping, the BRI aims to enhance regional connectivity through infrastructure development and investments across Asia, Europe, and Africa (Zhang and Wu, 2017). State-controlled media portrays the BRI as a manifestation of China’s commitment to global cooperation, promoting themes of inclusivity, mutual benefit, and shared prosperity (Zeng and Sparks, 2019).

While state narratives emphasize partnership and win-win outcomes, user-generated content often reflects skepticism toward Western involvement and concerns about geopolitical competition (Shi and Zhang, 2024). Commenters on digital platforms sometimes frame the BRI as part of China’s strategic competition with the West, reinforcing borders that emphasize distinct national interests (Zhang and Xu, 2022).

This divergence illustrates the complexities of border-making within Chinese nationalism. While the state promotes a diplomatic and cooperative image through the BRI, popular nationalism often constructs more exclusionary and confrontational borders, reinforcing narratives of Chinese superiority and resistance to foreign influence (Yang and Zheng, 2012). These differences highlight the tensions between state-led efforts to project unity and grassroots expressions that reflect deeper geopolitical anxieties.

The BRI serves as a microcosm of the interplay between state-led and popular nationalism, illustrating how borders are constructed, contested, and reshaped across different levels of discourse. The state’s portrayal of the initiative as an inclusive global project aligns with its desire to enhance China’s international legitimacy, while popular nationalist responses reveal the persistence of exclusionary sentiments that complicate the state’s diplomatic objectives. The competing narratives surrounding the BRI demonstrate that borders are fluid, continually negotiated spaces, influenced by both state narratives and public sentiment (Zhang and Xu, 2022).

The BRI case study underscores the dynamic and multifaceted nature of nationalism in contemporary China, reflecting the broader processes through which national identity and borders evolve. As digital platforms increasingly become spaces for public participation and expression, the tension between state and popular nationalism will remain central to understanding how China constructs its national identity and navigates its role on the global stage. This complex interaction between top-down state control and bottom-up grassroots mobilization exemplifies the challenges of managing national identity in an era shaped by globalization, digital media, and shifting geopolitical landscapes.

3 Research methodology

This study adopts a mixed-methods approach to examine how state-led and popular nationalism in China construct and reinforce borders through media narratives and user-generated content related to the BRI. By integrating quantitative and qualitative methods, the analysis captures both measurable linguistic patterns and deeper emotional and ideological undercurrents. This methodological combination provides a comprehensive lens to explore the divergences between state-led narratives and public discourse, illuminating how these forms of nationalism shape national identity within the Chinese context.

3.1 Research design and rationale

The research design combines quantitative methods (word frequency and sentiment analysis) with qualitative interpretation, aligning with theoretical frameworks on nationalism, populism, and border studies. Quantitative methods measure patterns in language, sentiment, and emotion, offering objective insights into how state-led and public discourses differ. In contrast, qualitative analysis reveals the underlying emotional and thematic currents within the narratives, adding depth and context to the statistical findings (Creswell and Vicki, 2017).

This dual approach ensures a nuanced understanding of how nationalism operates across both state-controlled media and digital platforms. By exploring both textual content and its emotional resonance, the methodology highlights how symbolic borders are articulated and contested. The mixed-methods framework aligns with the research questions, providing a systematic structure for investigating the construction of borders through state-led and popular nationalist expressions.

3.2 Data collection

The Global Times was selected as the primary data source due to its function as a state-controlled media outlet, advancing the CCP’s perspectives on international affairs (Zeng and Sparks, 2019; Zhang and Wu, 2017). As a subsidiary of the People’s Daily, the Global Times serves as a platform for disseminating state-led nationalism, adopting a nationalistic tone that closely aligns with government policy goals (Hatef and Luqiu, 2018).

The English-language edition was chosen for more than computational convenience. It reflects the CCP’s effort to engage global audiences and promote Chinese nationalism on the international stage (Edney, 2014). Unlike the Chinese edition, which caters primarily to a domestic audience, the English version targets foreign readers, expatriate communities, and English-speaking Chinese nationals, shaping global perceptions of China’s role. This edition places a greater emphasis on state narratives, with limited influence from grassroots or populist discourse (Zeng and Sparks, 2019).

User-generated comments on these articles provide crucial insights into popular nationalism, offering a glimpse into how international readers and English-speaking Chinese nationals engage with state narratives. These comments present a unique perspective on how public discourse reflects, challenges, or diverges from official rhetoric, revealing how popular nationalism operates in parallel with state-led narratives.

The study focused on articles containing the keyword “Belt and Road Initiative” to ensure relevance to the research topic. Articles limited to video or photo content were excluded to maintain the integrity of the textual analysis. The selected time frame—August 2021 to February 2024— captures a period of intensifying geopolitical tensions and significant developments in the BRI, providing a rich context for examining nationalist discourse.

The final dataset includes 287 articles, but only 16 featured public comments. Most comments clustered around the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, held on October 17–18, 2023. This concentration suggests that public engagement peaks during high-profile geopolitical events, especially those that evoke nationalist sentiments. To ensure analytical focus, the study narrowed its scope to 13 articles directly related to the Forum, facilitating a targeted exploration of how popular nationalism engages with state-led narratives during key diplomatic moments.

The limited number of comments reflects challenges in capturing public sentiment, likely due to moderation policies, strategic curation, or reduced engagement on less controversial topics. While this limitation affects the generalizability of the findings, the available comments offer meaningful insights into the interaction between state-led and popular nationalism. The study treats these insights as exploratory, calling for cautious interpretation of the results.

3.3 Data processing and text preparation

The textual data from Global Times articles and user comments was collected using web-crawling techniques and processed with the R programming language. The tidytext package (Silge and Robinson, 2017) facilitated tokenization, breaking the text into individual words. To focus on meaningful content, stop words (e.g., “the,” “and”) were removed. Additional preprocessing included lowercasing, punctuation removal, and contraction handling to ensure consistency across the dataset.

3.4 Analytical procedures

The word frequency analysis identifies the most frequently used words, revealing the thematic priorities of both state-led narratives and user-generated comments. After tokenization and preprocessing, word counts were calculated and visualized through bar charts and word clouds using the ggplot2 package (Wickham and Grolemund, 2017). State-led narratives were expected to emphasize themes of cooperation and development, aligning with China’s diplomatic goals. Meanwhile, user-generated comments were anticipated to focus on competition and superiority, reflecting more confrontational nationalist sentiments.

The sentiment analysis assesses the emotional tone of the texts by classifying words as positive or negative using the Bing Liu lexicon (Hu and Liu, 2004). Words were matched with sentiment labels through the inner_join function in R, and sentiment scores were calculated using the following formula:

This method enabled a comparative analysis of the emotional tone in state-led narratives and public discourse. State-controlled articles were expected to convey positive sentiment, emphasizing cooperation and diplomacy, while user comments were anticipated to exhibit more negative sentiment, expressing skepticism toward the BRI.

To capture nuanced emotional expressions, the study applied the NRC Emotion Lexicon (Mohammad and Turney, 2013). This lexicon categorizes words into eight emotions: anger, anticipation, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise, and trust. Tokenized words were merged with the NRC lexicon, and emotional frequencies were calculated and normalized for text length. The analysis expected that user-generated comments would display stronger negative emotions—such as anger and fear—compared to the more controlled emotional tone of state-led narratives.

3.5 Methodological rigor and limitations

The study ensures methodological rigor by employing well-established lexicons (Bing Liu and NRC) for sentiment and emotional categorization. Detailed documentation of data processing and analytical steps enhances reproducibility and reliability. Ethical considerations were carefully addressed: all data were publicly available, and no personally identifiable information was collected. The research maintained a responsible approach, avoiding any misinterpretation or misuse of content.

The small sample size of user comments limits the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. This constraint underscores the exploratory nature of the study, offering preliminary insights while highlighting the need for future research with broader datasets. Additionally, the focus on English-language texts may overlook nuances in Chinese-language discourse. However, the choice aligns with the study’s objective to explore state narratives intended for international audiences and leverages advanced NLP tools available for English-language analysis.

3.6 Alignment with research questions

The chosen methodology aligns closely with the study’s research questions by systematically investigating the role of state-led and popular nationalism in border construction. The analysis of Global Times articles demonstrates how state-led nationalism builds symbolic borders by emphasizing cooperation, development, and mutual benefit. In contrast, user-generated comments reveal popular nationalism’s divergence from official narratives, highlighting skepticism and framing borders around ideological competition.

This comparative analysis illuminates the interplay between nationalism, populism, and border-making, addressing the core research questions. By integrating quantitative and qualitative insights, the study offers a critical perspective on how national identity and symbolic borders are negotiated through both top-down state narratives and bottom-up public sentiment.

4 Findings

This section presents the results of the analysis, examining how state-led and popular nationalism construct and reinforce borders within the Chinese context of the BRI. The study draws on word frequency analysis, sentiment analysis, and emotional categorization to explore the distinct priorities reflected in the state-led Global Times articles and user-generated content. Finally, this section addresses the core research questions based on these analytical insights.

4.1 Word frequency analysis

The word frequency analysis highlights the key themes that characterize both the state-led narratives and public discourse, revealing contrasting priorities in the construction of borders.

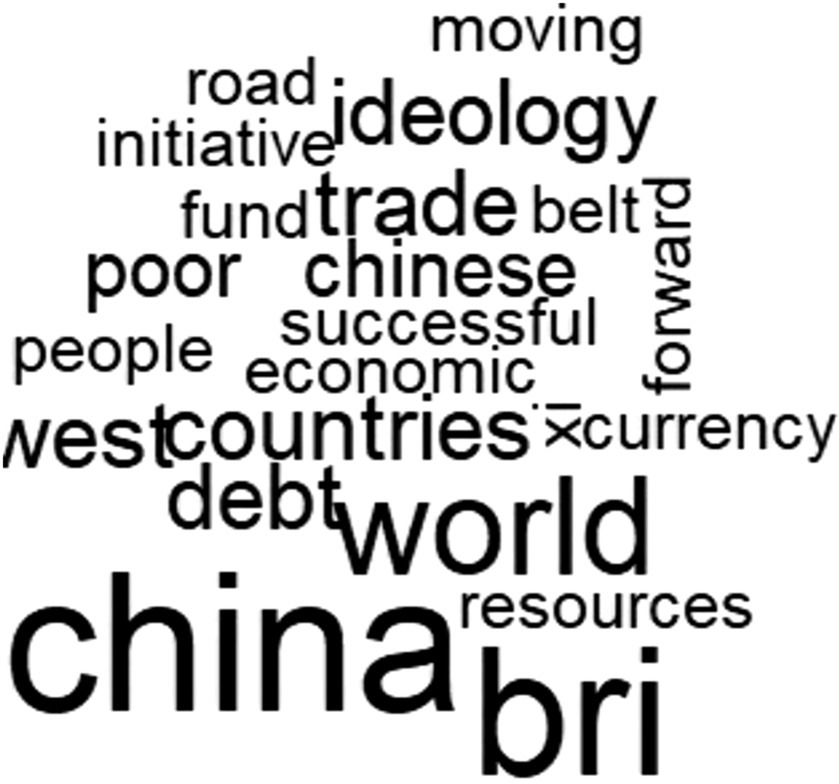

In the Global Times articles, the frequent use of words such as “China,” “cooperation,” “development,” “world,” “countries,” and “global” (Figure 1) indicates a deliberate attempt to frame the BRI as a collaborative project rooted in partnership and shared prosperity. This language aligns with China’s diplomatic efforts to position itself as a global leader committed to stability and growth (Zhang and Wu, 2017). The repeated emphasis on “cooperation” and “development” portrays the BRI as a vehicle for mutual benefit, drawing countries into a cooperative framework focused on shared goals (Arifon et al., 2019). Terms like “global” and “world” further reinforce China’s aspiration to project itself as a responsible power promoting international stability (Zhang and Jamali, 2022).

In contrast, the user-generated comments prioritize geopolitical competition and ideological divisions. Words such as “West,” “ideology,” and “China” (Figure 2) reflect concerns about rivalry between China and Western powers, framing the BRI as part of a broader struggle rather than a purely cooperative venture. This language constructs sharp borders that separate China from its perceived geopolitical rivals, highlighting national pride and the desire to assert China’s superiority (Yang and Zheng, 2012). While the state narrative seeks to promote inclusive borders that encourage cooperation, the public discourse reinforces exclusionary borders driven by ideological tensions and opposition.

These contrasting priorities reveal a clear divergence in how state-led and popular nationalism frame borders. The state narrative employs themes of cooperation and inclusion to foster diplomatic partnerships, while public discourse constructs borders based on opposition and competition, reflecting a more confrontational approach to China’s international role.

4.2 Sentiment analysis

The sentiment analysis provides further insight into the emotional framing of state-led and popular narratives, demonstrating the divergent ways in which these narratives construct symbolic and exclusionary borders.

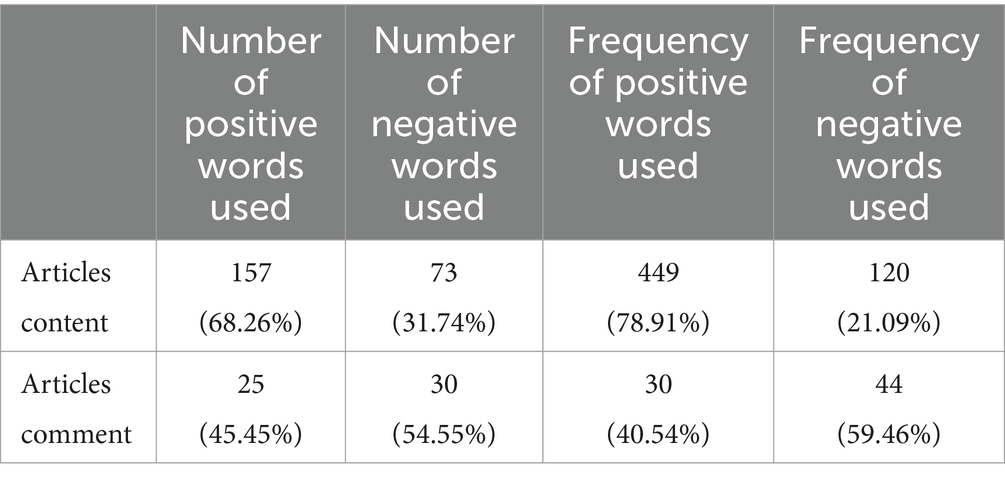

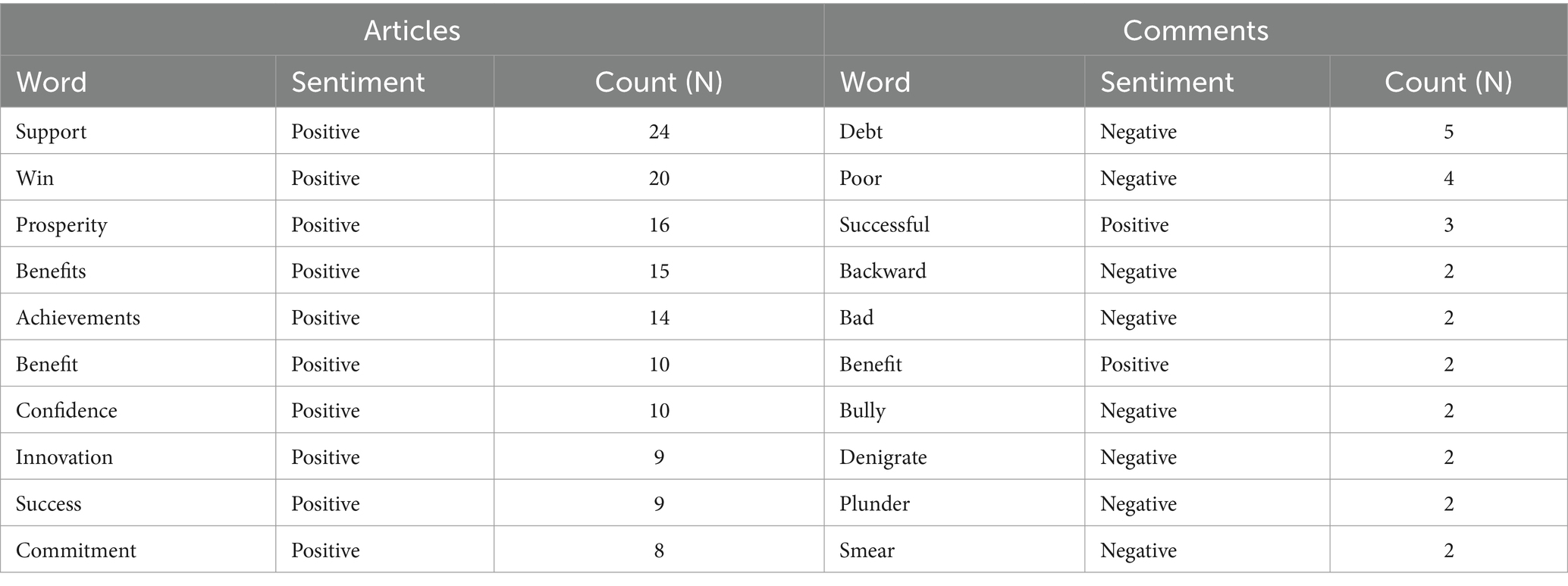

As summarized in Table 1, the Global Times articles emphasize positive words such as “support,” “prosperity,” and “benefits,” projecting the BRI as a constructive initiative that fosters success and mutual gain. In contrast, the comments feature more negative words, including “debt” and “poor,” reflecting skepticism toward the BRI and concerns about its geopolitical implications.

Table 1. Overview of output structure using “Head” syntax for sentiment analysis of articles and comments.

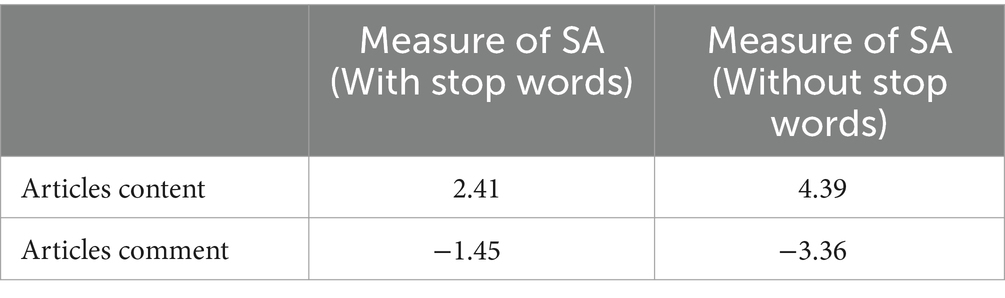

The frequency distribution of positive and negative words, shown in Table 2, further reinforces this divergence. In the Global Times articles, 68.26% of sentiment-laden words carry positive connotations, while 31.74% are negative. This distribution supports the CCP’s effort to promote the BRI as a symbol of cooperation. In contrast, only 45.45% of the words in the comments are positive, with 54.55% being negative, highlighting the public’s critical stance toward the initiative.

To capture the magnitude of this divergence, Table 3 presents the sentiment scores for both the articles and the comments. The articles yield a positive score of 2.41 with stop words, rising to 4.39 without them, reflecting the optimistic tone of the state’s messaging. Meanwhile, the comments yield a negative score of −1.45 with stop words, which deepens to −3.36 when stop words are removed, indicating a more skeptical and critical tone in public discourse.

These results reveal contrasting emotional frameworks. The state-led narrative uses positive sentiment to construct borders that emphasize cooperation, while the public employs negative sentiment to build exclusionary borders rooted in concern over the BRI’s economic and geopolitical risks.

4.3 Emotional categorization using NRC emotion lexicon

The emotional categorization captures more nuanced emotional states beyond broad positive and negative classifications, offering deeper insights into the emotional underpinnings of state-led and popular nationalism.

The Global Times articles primarily convey positive emotions such as “trust,” “anticipation,” and “joy,” reinforcing the state’s portrayal of the BRI as a successful and beneficial initiative. The limited presence of negative emotions like “anger” and “fear” suggests a deliberate effort to maintain a positive and controlled narrative aligned with China’s diplomatic goals.

By contrast, the comments express heightened levels of negative emotions such as “anger,” “fear,” and “annoyance.” These emotions reflect frustrations with perceived geopolitical threats and skepticism about the BRI’s outcomes, revealing a more confrontational stance toward China’s international role.

Figure 3 visualizes the emotional strength across eight categories in both the articles and comments. As the figure shows, positive emotions such as “happy” and “inspired” dominate the state-led narratives, while negative emotions like “afraid,” “angry,” and “annoyed” prevail in the user-generated comments.

Figure 3. Comparison of emotional strength across eight emotions in articles and comments on Global Times.

These contrasting emotional profiles highlight the divergent strategies underlying state-led and popular nationalism. The state emphasizes positive emotions to construct borders of stability and cooperation, while the public relies on negative emotions to express opposition and reinforce exclusionary borders based on geopolitical tensions.

4.4 Integration with theoretical framework

The findings align with theoretical frameworks on nationalism, populism, and border studies, illustrating how state-led and popular nationalism construct different types of borders. The state’s use of positive sentiment and emotions such as trust and anticipation reflects its effort to build inclusive borders that promote cooperation and partnership, projecting China as a responsible global leader (Zeng and Sparks, 2019).

In contrast, the negative sentiment and emotions expressed in the comments align with populist discourses that emphasize exclusionary borders, defining “the people” in opposition to external actors, particularly Western powers (Brubaker, 2017; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017). The recurring use of terms like “debt,” “threat,” and “bully” reflects a narrative that frames the BRI as a contested geopolitical project, aligning with the broader populist tendency to mobilize public sentiment against perceived external threats (Laclau, 2005).

These findings not only align with the theoretical frameworks of nationalism and populism but also provide direct answers to the research questions that guide this study. In the following section, we address these questions by synthesizing key insights from the analyses.

4.5 Addressing the research questions

The analysis presented in the previous sections offers insights that directly address the three core research questions guiding this study.

RQ1: How does state-led nationalism, as expressed in media coverage of the BRI, construct borders to define China’s national identity and its role in the world?

The analysis of Global Times articles demonstrates that state-led nationalism constructs symbolic borders through themes of cooperation, development, and mutual benefit. Frequent references to “cooperation,” “development,” and “global” underscore the BRI as a project fostering international collaboration, aligning with the Chinese government’s diplomatic narrative of inclusivity and stability (Zeng and Sparks, 2019; Zhang and Wu, 2017). These narratives portray China as a responsible global leader committed to regional development and international cooperation (Zhao and Zhang, 2024; Zhang and Jamali, 2022).

The emotional tone in these articles further reinforces this inclusive framing. High frequencies of trust, anticipation, and joy reflect the state’s effort to build permeable borders that invite participation from other nations. The emotional narrative aims to cultivate trust in China’s rise as a peaceful power and frame the BRI as a tool for achieving mutual prosperity. Such symbolic borders serve not only to legitimize China’s global influence but also to consolidate a sense of national identity centered on international cooperation. These findings align with theories suggesting that state-led nationalism often employs inclusive narratives to strengthen political legitimacy and advance foreign policy goals (Liu and Ma, 2018; Yuval-Davis et al., 2019).

RQ2: How does popular nationalism, as reflected in user-generated content on BRI-related articles, construct borders that may diverge from or challenge state narratives?

In contrast to the cooperative tone of state-led narratives, user-generated comments frame the BRI within a context of ideological competition and geopolitical rivalry. References to “the West” and “ideology” reflect widespread public concerns that the BRI represents more than just development cooperation—it symbolizes a contest between Chinese and Western influence (Shi and Zhang, 2024). This framing constructs rigid, exclusionary borders, positioning China as distinct and superior to external powers, while also portraying international engagement as a potential threat to national interests.

These findings align with Brubaker’s (2017) observation that populist nationalism thrives on the construction of emotional and symbolic borders. User-generated content reflects public efforts to frame the BRI not just as an economic initiative but as a site of ideological struggle. Through emotional narratives—often emphasizing anger, fear, and pride—commenters reinforce exclusionary identities, drawing a clear line between “us” (China) and “them” (the West). These emotionally charged borders demonstrate how popular nationalism expresses resistance to foreign influence, even when such resistance complicates the government’s diplomatic narrative.

This divergence between state-led and popular nationalism reflects the tensions between top-down efforts to promote cooperation and bottom-up expressions of skepticism and pride. The public’s use of digital platforms to construct exclusionary narratives complicates the state’s attempts to control the narrative and maintain social cohesion. While the state emphasizes inclusive borders to support diplomatic goals, public discourse constructs exclusionary borders rooted in ideological opposition, underscoring the dual nature of nationalism in the digital era.

RQ3: What are the implications of these constructions for understanding the interplay between nationalism, populism, and border-making in the Chinese context?

The findings highlight the complex interplay between state-led and popular nationalism in constructing symbolic and ideological borders. State-led nationalism employs themes of inclusion and cooperation to project China’s global leadership, while popular nationalism constructs exclusionary borders that express public skepticism and assert national superiority. This duality demonstrates that nationalism in China operates on multiple levels, shaped by both government narratives and public sentiment (Zhao, 2005; Zhang, 2022).

This interaction aligns with theoretical perspectives on the intersection of nationalism and populism, where populist discourses often mobilize “the people” in opposition to external forces (Laclau, 2005; De Cleen and Stavrakakis, 2017). As Brubaker (2017) notes, populist nationalism gains strength by constructing symbolic borders that emotionally separate insiders from outsiders. In the Chinese context, digital platforms provide a critical space for these dynamics, where user-generated content shapes nationalist discourse in ways that may challenge state narratives.

The findings also demonstrate that border-making processes are dynamic, evolving through both top-down efforts by the state and bottom-up public expressions. These processes reflect how symbolic borders are continuously renegotiated, shaping perceptions of national identity and China’s geopolitical role (Yuval-Davis et al., 2019). The interplay between state and popular nationalism suggests that maintaining social cohesion and diplomatic consistency will require the Chinese government to address public concerns and incorporate grassroots sentiments into its strategic narratives. At the same time, international actors engaging with China must recognize the dual nature of nationalist discourse—balancing official narratives with awareness of exclusionary public sentiment to navigate complex diplomatic relationships.

4.6 Implications of findings

The findings carry significant implications for both domestic governance and international relations. The state’s reliance on positive sentiment and optimistic framing aims to present the BRI as a symbol of global leadership and cooperation. However, the public’s expression of negative emotions and skepticism reveals a gap between state narratives and public sentiment, posing potential challenges for social cohesion.

This divergence suggests that the CCP must address popular nationalist concerns to maintain domestic stability and prevent discontent from undermining its foreign policy goals. Unaddressed public skepticism could generate pressure on policymakers, complicating China’s diplomatic engagements.

For international actors, understanding the dynamic interplay between state-led and popular nationalism is essential. While the state projects cooperation and stability, popular nationalist discourse emphasizes exclusion and competition, potentially influencing diplomatic relations.

The sentiment patterns in Tables 1–3, along with the emotional profiles in Figure 3, underscore the complex and evolving nature of border construction. These findings align with the theoretical expectation that borders are not static but constantly reshaped through both top-down and bottom-up processes (Yuval-Davis et al., 2019). The interplay between state-led and popular nationalism reflects the fluidity of national identity and the ongoing negotiation of symbolic and emotional borders.

5 Discussion and conclusion

This section interprets the findings in relation to the theoretical frameworks of nationalism, populism, and border studies. It addresses the research questions, highlights the broader academic contributions, and explores the implications for understanding the interplay between state-led and popular nationalism in China. The discussion critically engages with the literature to situate the study within ongoing debates, identifying both the strengths and limitations of the research.

5.1 Implications for theory and practice

5.1.1 Theoretical contributions

The findings provides preliminary insights into the interplay between state-led and popular nationalism and highlights future research directions for border studies. This study highlights the critical role of media narratives and user-generated content in constructing national identity, showing how both state and public expressions engage in boundary-making processes (Brubaker, 2017; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017). These findings reveal the centrality of emotions in populist discourse, emphasizing how emotional expressions influence how borders are drawn between “us” and “them” (Laclau, 2005; De Cleen and Stavrakakis, 2017).

Through the case of the BRI, the study demonstrates that foreign policy initiatives do more than facilitate international cooperation; they also serve as critical platforms for the expression of nationalist sentiments. The BRI functions as a dual site, where the state uses inclusive rhetoric to promote partnership, while public discourse frames it as part of an ideological competition, reinforcing exclusionary boundaries (Zhang and Wu, 2017; Arifon et al., 2019). These dynamics align with theoretical perspectives that conceptualize borders as socially constructed and constantly reshaped through discourse and public interaction, challenging the idea that borders are merely physical or territorial (Yuval-Davis et al., 2019).

This research underscores that nationalism operates as both a top-down and bottom-up process, shaped by state narratives and grassroots sentiment. The findings extend the understanding of how populism intersects with nationalism, illustrating how populist rhetoric often arises within nationalist frameworks, particularly through digital spaces where public sentiment can gain momentum independent of state control (Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez, 2020). These insights underscore the complexity of border-making processes in the digital age, where different actors participate in constructing and contesting national identity.

5.1.2 Practical implications

The divergent ways in which state-led and popular nationalism construct borders carry several significant implications for domestic governance, international diplomacy, and media strategies. Recognizing these differences is essential for actors seeking to engage with China’s evolving national identity and global ambitions.

Maintaining social cohesion requires the CCP to address the gap between its inclusive narratives and the exclusionary sentiments expressed by segments of the public. The emotional intensity observed in user-generated comments suggests that popular nationalism, if left unaddressed, could escalate into public discontent, complicating the state’s ability to align domestic sentiment with its foreign policy objectives (Zhao, 1998; Zhang, 2022). Bridging this gap will require responsive governance that accounts for the public’s emotional responses to international developments.

Foreign actors engaging with China must also recognize that popular nationalist sentiment can shape public perceptions and influence diplomatic relations. Although the state-controlled narrative presents the BRI as a symbol of cooperation, exclusionary rhetoric in public discourse reflects a more confrontational stance, creating challenges for international engagement (Shi and Zhang, 2024). Diplomats and policymakers must navigate these dual narratives to develop strategies that account for both official and public sentiment when engaging with China.

Effective media strategies must also respond to the emotional and ideological dimensions identified in this study. State-controlled media and user-generated platforms play pivotal roles in shaping national identity, and both function as arenas for negotiating the meaning of borders. Policymakers and media practitioners must recognize the importance of emotional narratives and consider how to frame communication strategies that resonate with public sentiment while supporting state objectives (Carlson, 2007; Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez, 2020).

This study demonstrates that media narratives and public discourse do not operate in isolation but instead influence one another, contributing to the dynamic construction of national identity. Understanding this interplay will remain essential for domestic policymakers and international actors as China continues to assert itself globally. The emotional and ideological dimensions of nationalist discourse cannot be overlooked, as they shape not only perceptions of national identity but also the direction of China’s global engagement.

5.2 Limitations and suggestions for future research

While this study provides valuable insights into the interplay between state-led and popular nationalism in the context of the BRI, several limitations must be acknowledged. These constraints highlight the exploratory nature of the findings and point to areas for future research.

5.2.1 Small sample size and limited generalizability

The study’s dataset includes only 13 articles and their corresponding comments, reflecting the challenges of collecting public sentiment data from moderated platforms. This small sample limits the generalizability of the findings and constrains the scope of the conclusions. Although sentiment analysis provides meaningful insights into emotional trends, computational methods such as these may encounter reliability issues when applied to small datasets. Future research should explore larger datasets from multiple platforms to validate and build upon these initial findings.

5.2.2 Limited scope of user-generated content

Given the focus on user-generated comments from the Global Times, the study captures only a narrow segment of public discourse. User engagement on other social media platforms, such as Weibo or WeChat, likely reflects a broader and more diverse range of opinions. Additionally, moderation policies on platforms like Global Times may affect which comments are visible to the public, potentially skewing the analysis. Future studies should expand the dataset to include user-generated content from both Chinese and international platforms to provide a more comprehensive understanding of public sentiment.

5.2.3 Language constraints

This study primarily analyzes the English-language edition of the Global Times to focus on state narratives intended for international audiences. However, this approach may overlook nuances present in Chinese-language discourse. As public nationalism in China is often expressed more intensely in domestic forums, future research should incorporate Chinese-language sources to explore how language and audience shape nationalist expressions differently across domestic and international contexts.

5.2.4 Challenges in identifying demographic and motivational patterns

The anonymity of user-generated content limits the ability to infer the demographic background or motivations of the commenters. As a result, the study cannot capture the underlying drivers of individual expressions of nationalism or how public discourse varies across different social groups. Future research could incorporate qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, to gain deeper insights into the attitudes and motivations of participants in nationalist discourse.

5.2.5 Methodological considerations for future studies

The study demonstrates the potential of sentiment and emotional analysis in exploring the dynamics of state-led and popular nationalism. However, the small sample size raises questions about the effectiveness of computational methods for such limited datasets. Future studies should explore mixed-method approaches that combine computational techniques with qualitative analysis to ensure a richer interpretation of results. In addition, comparative studies across different geopolitical contexts could help identify broader patterns and divergences in the interaction between nationalism, populism, and border-making processes.

5.2.6 Opportunities for comparative research

While this study focuses on China’s unique context, the interplay between state-led and popular nationalism is not exclusive to China. Comparative research across different political systems and cultural settings could provide valuable insights into how state and public actors construct and contest symbolic borders. Such research could also explore how digital media platforms shape nationalist discourse in different regions, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the intersection between nationalism, populism, and media in global contexts.

In summary, while the findings of this study offer preliminary insights into the dynamics of nationalism and border-making in China, they also highlight the need for broader and more diverse research. Expanding the scope of future studies—through larger datasets, comparative analysis, and mixed methods—will be essential for deepening our understanding of how state and public narratives shape national identity and geopolitical borders in the digital age.

5.3 Conclusion

This study has explored how state-led and popular nationalism in China construct and contest borders through media narratives and user-generated content related to the BRI. The findings highlight two distinct approaches to border-making: state-led nationalism, expressed through media coverage, emphasizes inclusion, cooperation, and global leadership, while popular nationalism, reflected in user-generated comments, reinforces exclusionary borders grounded in ideological opposition and geopolitical competition. This divergence reveals the dynamic interplay between top-down state narratives and bottom-up public sentiment in shaping national identity and geopolitical boundaries.

The analysis of Global Times articles shows how the state constructs symbolic borders by framing the BRI as a platform for partnership and mutual development, aligning with China’s strategic objective to enhance its global influence. This narrative emphasizes positive emotions—such as trust, anticipation, and joy—and reinforces China’s image as a responsible global actor committed to fostering cooperation. In contrast, user-generated comments frame the BRI within a context of competition and rivalry, expressing skepticism toward state narratives and highlighting tensions between China and Western powers. These comments often reflect negative emotions—such as anger, fear, and pride—reinforcing exclusionary identities that complicate the state’s diplomatic goals.

The divergence between state-led and popular nationalism underscores the challenges the Chinese government faces in maintaining social cohesion and managing public sentiment in an era where digital platforms enable grassroots voices to challenge official narratives. While the state seeks to project a cooperative image through inclusive borders, public discourse reinforces exclusionary boundaries that emphasize China’s distinctiveness and superiority. This duality exemplifies how nationalism in China operates at multiple levels, with both unifying and divisive dynamics shaping national identity and influencing the country’s role in the global order.

The findings align with theoretical perspectives that view borders as socially constructed and constantly negotiated through interactions between state and public actors (Yuval-Davis et al., 2019). As Brubaker (2017) argues, populist nationalism thrives on the construction of emotional and symbolic borders, and this study demonstrates how user-generated content on digital platforms amplifies exclusionary narratives, complicating state-led efforts to promote cooperation. These findings suggest that border-making processes are fluid and reflect both cooperative aspirations and contested identities within China’s national discourse.

As China continues to expand its global reach, understanding the evolving dynamics between state-led and popular nationalism will be essential for both domestic governance and international engagement. The state must navigate the tensions between its inclusive rhetoric and the exclusionary sentiments expressed by segments of the public to ensure social stability and align domestic sentiment with its foreign policy objectives. Unaddressed public skepticism toward initiatives like the BRI could create domestic pressure on policymakers, leading to unintended shifts in diplomatic strategies.

For international actors, recognizing the dual nature of China’s nationalist discourse will be critical. While official narratives emphasize partnership and stability, public discourse reflects ideological opposition and geopolitical rivalry. This divergence requires diplomats, policymakers, and businesses engaging with China to balance their strategies by acknowledging both state-led narratives and grassroots sentiment.

In summary, this study offers preliminary insights into the interplay between state-led and popular nationalism in the context of the BRI, emphasizing the need for further research to explore how these dynamics evolve across different geopolitical contexts. Future studies could employ larger datasets, incorporate comparative research across other political systems, and explore mixed methods to better understand how state and public actors negotiate national identity and geopolitical boundaries. As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, understanding these complex dynamics will be essential for navigating the shifting geopolitical landscape and fostering constructive international relations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

CL: Writing – review & editing. JK: Writing – original draft. AC: Writing – original draft. BP: Writing – original draft. W-KM: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work received partial support from the SIRG - CityU Strategic Interdisciplinary Research Grant (No. 7020093).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

Arifon, O., Huang, Z. A., Zheng, Y., and Melo, A. Z. (2019). Comparing Chinese and European discourses regarding the “belt and road initiative”. Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication. doi: 10.4000/rfsic.6212

Carlson, M. (2007). Order versus access: news search engines and the challenge to traditional journalistic roles. Med. Cult. Soci. 29, 1014–1030. doi: 10.1177/0163443707084346

Creswell, J. W., and Vicki, P. L. C. (2017). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 3rd Edn. Los Angeles, Calif London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Melbourne: SAGE Publications, Inc.

De Cleen, B., and Stavrakakis, Y. (2017). Distinctions and articulations: A discourse theoretical framework for the study of populism and nationalism. Javnost - The Public 24, 301–319. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083

Edney, K. (2014). “Strategic interaction: global times and the Main melody” in The globalization of Chinese propaganda: International power and domestic political cohesion (pp. 123–150). ed. K. Edney (New York, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US).

Hatef, A., and Luqiu, L. R. (2018). Where does Afghanistan fit in China’s grand project? A content analysis of Afghan and Chinese news coverage of the one belt. One Road initiative. International Communication Gazette 80, 551–569. doi: 10.1177/1748048517747495

He, D., and Tang, W. (2024). Constructed community: rise and Engines of Chinese Nationalism under xi Jinping. J. Contemp. China 1–23, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2024.2339303

Hu, M., and Liu, B. (2004). “Mining and Summarizing Customer Reviews.” In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 168–77. KDD ’04. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery.

Liu, C., and Ma, X. (2018). Popular threats and nationalistic propaganda: political logic of China’s patriotic campaign. Secur. Stud. 27, 633–664. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2018.1483632

Mihelj, S., and Jiménez-Martínez, C. (2020). Digital nationalism: understanding the role of digital media in the rise of ‘new’ nationalism. Nations National. 27, 331–346. doi: 10.1111/nana.12685

Mohammad, S. M., and Turney, P. D. (2013). Crowdsourcing a Word–Emotion Association Lexicon. Comput. Intell. 29, 436–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8640.2012.00460.x

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. 2nd. ed. Edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Shi, J., and Zhang, D. (2024). “Unravelling diverse Chinese discourses on the Russo-Ukrainian war: a comparative analysis of official and individual accounts on Weibo” in Tabe Bergman & Jesse Owen Hearns-Branaman, media, dissidence and the war in Ukraine (London: Routledge), 63–75.

Silge, J., and Robinson, D. (2017). Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach. 1st Edn. Beijing, China: O’Reilly Media.

Tang, W. (2016). Populist authoritarianism: Chinese political culture and regime sustainability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Valladares, T. L., Golino, H., and Coan, J. A. (2020). Identifying emotions in texts using the Emoxicon approach to compare right and left-leaning trolls on twitter. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/u8ghv

Wickham, H., and Grolemund, G. (2017). R for Data Science: Import, Tidy, Transform, Visualize, and Model Data. 1st Edn. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media.

Yang, Y., and Chen, X. (2020). Globalism or nationalism? The paradox of Chinese official discourse in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 26, 89–113.

Yang, L., and Zheng, Y. (2012). Fen Qings (angry youth) in contemporary China. J. Contemp. China 21, 637–653. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2012.666834

Yuval-Davis, N., Wemyss, G., and Cassidy, K. (2019). Bordering. 1st Edn. Cambridge, UK Medford, MA: Polity.

Zeng, W., and Sparks, C. (2019). Popular nationalism: global times and the US–China trade war. Int. Commun. Gaz. 82, 26–41. doi: 10.1177/1748048519880723

Zhang, C. (2022). Contested disaster nationalism in the digital age: emotional registers and geopolitical imaginaries in COVID-19 narratives on Chinese social media. Rev. Int. Stud. 48, 219–242. doi: 10.1017/S0260210522000018

Zhang, D., and Jamali, A. B. (2022). China's "weaponized" vaccine: intertwining between international and domestic politics. East Asia 39, 279–296. doi: 10.1007/s12140-021-09382-x

Zhang, D., and Qiu, X. (2022). “Cyber-nationalism in China: popular discourse on China’s belt road” in New nationalisms and China’s belt and road initiative: Exploring the transnational public domain. eds. J. Rajaoson and M. E. R. Mireille (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 143–156.

Zhang, L., and Wu, D. (2017). Media representations of China: a comparison of China daily and financial times in reporting on the belt and road initiative. Brand China Media 178–192. doi: 10.4324/9780429320224-12

Zhang, D., and Xu, Y. (2022). When nationalism encounters the COVID-19 pandemic: understanding Chinese nationalism from media use and media trust. Glob. Soc. 37, 176–196. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2022.2098092

Zhao, S. (1998). A state-led nationalism: the patriotic education campaign in post-Tiananmen China. Communis. Post-Commun. 31, 287–302. doi: 10.1016/S0967-067X(98)00009-9

Zhao, S. (2005). China's pragmatic nationalism: is it manageable? Wash. Q. 29, 131–144. doi: 10.1162/016366005774859670

Keywords: populism, nationalism, borders, Chinese media, digital identity, belt and road

Citation: Leung CK, Ko J, Cheung A, Pun BL-f and Ming W-K (2024) Borders of belonging: how Chinese nationalism constructs exclusion in the age of populism. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1501363. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1501363

Edited by:

Sabine Volk, University of Passau, GermanyReviewed by:

Dechun Zhang, Leiden University, NetherlandsKinga Polynczuk-Alenius, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland

Copyright © 2024 Leung, Ko, Cheung, Pun and Ming. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chun Kai Leung, Y2tsZXVuZ3pAaGt1Lmhr

Chun Kai Leung

Chun Kai Leung Jeremy Ko

Jeremy Ko Anthony Cheung

Anthony Cheung Boris Lok-fai Pun4

Boris Lok-fai Pun4 Wai-Kit Ming

Wai-Kit Ming